Am I Still Creative? The Effect of Artificial Intelligence on Creative Self-Beliefs

Funding: Maciej Karwowski was supported by a grant from the National Science Centre, Poland (grant number 2022/45/B/HS6/00372).

Angela Faiella and Aleksandra Zielińska contributed equally to this manuscript and should be considered co-first authors.

ABSTRACT

The advent of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is reshaping society, highlighting the need to better understand its implications for human creativity. This investigation explores the relationship and differences between people's general creative self-beliefs and their creative self-beliefs in an AI-specific context (i.e., while using AI tools). It further investigates the role played by AI-specific creative self-beliefs and AI-augmented creative activity for creative achievement. In a study on Prolific panel members (N = 273), we found that people's general creative self-beliefs were notably higher than their AI-specific beliefs (d = 0.75). Moreover, the relationship between general and AI-specific creative self-beliefs followed a necessary-yet-not-sufficient pattern; feeling creative in AI settings was unlikely when general creative self-beliefs were low, yet strong general creative self-beliefs did not guarantee feeling creative when using AI. Finally, although general creative self-beliefs were both directly and indirectly (via creative activity) positively associated with creative achievement, AI-specific beliefs were only indirectly linked to achievement via AI-augmented creative activities, with more puzzling direct links observed. We discuss the implications of these findings and offer some future research avenues.

1 Introduction

On November 30, 2022, a fully operational large language model (LLM), ChatGPT (Wu et al. 2023), went public. Trained on vast amounts of human-generated data extracted from the Internet, ChatGPT could not only complete truncated sentences in a statistically coherent way but also allow the emergence of new capabilities absent in smaller models (Wei et al. 2022). This technological advancement started the era of Generative AI raising the vital question of how this technology can dynamically integrate human creativity in the post-information society (Corazza 2016, 2019; Corazza et al. 2022).

Notably, Generative AI (Gen-AI) is more than LLMs. It refers to computational techniques that yield products such as text, images, or audio from training data (Feuerriegel et al. 2024). Consequently, although the initial forecast on the impact of AI on the job market was all concentrated on the risk of losing blue-collar jobs, the advent of Gen-AI demonstrated that perhaps the most crucial transformation would be on white collars and specifically in the creative industry (Anantrasirichai et al. 2025). After all, not only does Gen-AI produce any content, but it also generates content that could be considered original and meaningful. The future of human and AI creative contributions and their potential interactions in the creative process thus becomes a hot topic, provoking reactions from naïve enthusiasm on the one side and a visceral fear or skepticism on the other (Leiter et al. 2024; Qi et al. 2024).

While existing studies have focused on dueling human and AI creative outputs (e.g., Koivisto and Grassini 2023), the consequences of using AI tools in creative settings for human creative self-beliefs remain understudied. Does using AI in the creative process make people feel more creatively capable? Or does it result in people feeling overshadowed or replaced, considering the creative output no longer belongs to them? In this article, we delve into these questions, exploring the role of AI in people's creative self-beliefs, creative activity, and achievement.

1.1 AI and Creativity

Human-AI interactions have been conceptualized as ranging from a non-existing collaboration to complementing each other, to mutual dependence, and finally, a full synergy (Lubart et al. 2021; Rafner et al. 2023; Sowa et al. 2021). Within the creativity field, a recent manifesto (Vinchon et al. 2023) foresees four different scenarios for how the coexistence of humans and machines in creative endeavors might evolve. The first scenario is Co-cre-AI-tion, that is, a collaborative creative effort involving humans and Gen-AI, with mutual recognition. This leads to human creativity augmented by AI. The second scenario is labeled as Organic: creation by a human for humans, natural creativity. The third scenario, Plagiarism 3.0, corresponds to the case in which people with a propensity for creativity rely entirely on Gen-AI tools without citing the source. Finally, the Shutdown scenario corresponds to the case in which humans become less and less motivated to be creative due to competition from Gen-AI. The more optimistic scenario is arguably that of a future in which Co-cre-AI-tion is the most frequent approach, while the Organic scenario is preserved (perhaps for elite audiences), Shutdown is avoided, and Plagiarism is regulated by ethics and laws. This was one of the first steps in understanding the impact of Gen-AI tools on human creative actors' motivation, self-identity, and self-efficacy (see also: Watkins and Barak-Medina 2024).

The existing studies provided little empirical insights into how AI contexts for creativity affect people's creative self-beliefs. One recent investigation (Tang et al. 2024) focused on the collaboration between human participants and ChatGPT in generating solutions to creativity tasks. This study demonstrated that not only did human–human dyads generate more creative solutions than human–AI dyads, but also—more importantly for the current study—human–human collaboration increased people's creative self-beliefs, an effect that was not observed when human participants collaborated with AI. This finding might suggest that when people use AI (or collaborate with it), it might not necessarily benefit their feelings that they can think creatively.

1.2 Creative Self-Beliefs and AI Tools

Creative achievement in any domain is impossible without prolonged activity that involves training, learning the domain, and perfecting skills (Ericsson et al. 1993; Macnamara et al. 2014; Weisberg 2018). Activity is necessary for achievement (Zielińska et al. 2023), but what drives people's creative activity? A growing number of studies in recent years have focused on motivational and self-perception characteristics that explain a unique portion of variability in differences between people in creative activity. These factors were differently named, with the most often used label being creative self-beliefs (CSBs; Karwowski and Kaufman 2017; Karwowski, Lebuda, et al. 2019). As Beghetto and Karwowski (2023, 179) explain: “creative self-beliefs refer to constellations of self-beliefs that […] represent the core agentic component of creative action […] a necessary intervening factor in the link between people's potential to act creatively and their actual creative behavior.” In this work, we focus on the self-beliefs elements of creative agency, that is, creative confidence and centrality.

Creative confidence denotes “beliefs in one's ability to think or act creatively in and across performance domains” (Karwowski, Lebuda, et al. 2019, 399). It might be further divided into more dynamic creative self-efficacy and more static creative self-concept. Thus, creative self-efficacy is prospective (future-oriented), specific to a particular task and situation, and dynamic—changeable and malleable. Creative self-concept is based on more retrospective judgment (and, thus, being present-and-past oriented), is more general (i.e., holistic), stable (see Zandi et al. 2025), and comparative than creative self-efficacy. Previous operationalizations and measurements of creative confidence factors tended to confuse creative self-efficacy and creative self-concept (see discussion in Beghetto and Karwowski 2017, 2023). Thus, creative confidence as a broader umbrella term not only seems appropriate in most contexts but also well-aligned with many measures that, while claiming that they capture creative self-efficacy, instead focus on creative self-concept (see Beghetto and Karwowski in press; Marsh et al. 2005, 2019; Zielińska, et al. 2022).

Creative centrality refers to the “value, merit, or worth of creativity in relation to one's broader sense of self” (Karwowski, Lebuda, et al. 2019, 400). This aspect of creative agency was previously termed as creative personal identity (Karwowski et al. 2018) or creative role identity (when it was applied in the work context, e.g., Farmer et al. 2003; Huang 2024; Wang and Cheng 2010), or simply perceived value of creativity (Karwowski and Beghetto 2019; Karwowski, Lebuda, et al. 2019). Creative centrality denotes the importance of creativity and being creative for an individual, the place creativity occupies in one's identity. Therefore, the term creative centrality seems more appropriate than previously used labels.

What drives creative confidence and centrality, and how can we influence them? The way people view themselves and their creative potential is a product of various sociopsychological factors, making these self-beliefs malleable and alterable under different contextual influences. While one's prior experiences, the “enactive attainments” (Bandura 1986), may be the most powerful source of one's perceived agency, people also draw inferences about their capabilities from social persuasion (e.g., encouraging feedback) or vicarious experiences (e.g., seeing or visualizing how other agents would cope with a challenge). This makes human–AI interactions potentially formative for creative self-beliefs. Not only do these interactions deliver new experiences prompting self-reflection, but they can also provide immediate reactions from AI—a source that a person can potentially trust and rely on.

1.3 AI's Empowering vs. Detrimental Effects on Creative Self-Beliefs

The question of whether a person's creative self-beliefs will be enhanced or endangered within AI settings remains open. Although the lack of intentionality and self-direction in any existing AI model precludes its creative agency, the conversational style many such tools operate in might exaggerate a person's tendency to attribute human-like characteristics—including agentic involvement—to artificial systems (Deshpande et al. 2023), also known as the ELIZA effect (Weizenbaum 1966). This can result in varied dynamics and trade-offs between human and AI contributions to the creative process, where AI is seen either as an assistant empowering human creativity, a “co-agent” working collaboratively, or even an autonomous agent requiring minimal or no human input.

This threat by AI and the need to retain one's own agency were demonstrated in a small qualitative study (Sowa et al. 2021), showing that people might prefer AI to be reactive and submissive rather than proactive and challenging, as they would expect from human collaborators. In contrast, embracing AI as an actual creative agent (“AI is creative just like me, or even more so”) might be demotivating, leading people to rely entirely on AI output rather than using it to support their thinking. Indeed, in educational studies where AI usage consequences for the learning process are widely discussed, it has been shown that both active and reactive approaches are adopted when working with AI (Yang et al. 2024). On the one hand, interacting with AI can trigger an active, reflective approach, where people acknowledge the creativity-enhancing possibilities these tools provide while still drawing on their personal resources, thinking critically, and asserting control over the process, thus augmenting their sense of agency. On the other hand, people's attitudes can become more receptive toward AI, approving outputs without much critical processing and engagement of their own resources, which can be detrimental to their perceived creative agency. Such self-belief changes might explain why students who initially learn more effectively with AI lose the observed benefits once the support is removed (Darvishi et al. 2024). Although current performance might be strengthened, overreliance on AI can impair agency, making people less likely to learn from the experience and develop effective self-regulatory strategies that could help deal with future challenges, with or without AI support.

Finally, while both scenarios for AI's empowering versus detrimental effects on human agency are likely, the case where one's creative confidence and centrality are low but are elevated when interacting with AI appears less plausible. If people do not consider themselves creative overall, they are unlikely to feel much different simply using AI tools. Instead, they might view AI as a crutch rather than a complement to their abilities, with the AI becoming a substitute for their creative effort. Moreover, given the essential role of self-beliefs in actuating creative behavior (Karwowski and Beghetto 2019), people with limited agentic resources are unlikely to engage with AI for creative purposes in the first place, resulting in limited opportunities for developing high AI-specific creative self-beliefs. This suggests that while strong personal creative self-beliefs might not guarantee feeling creatively empowered during interactions with AI, low levels of personal creative self-beliefs can make this impossible. Put differently, general creative self-beliefs could act as a necessary yet not sufficient condition for AI-specific self-beliefs.

At the same time, success in AI-specific creative contexts may require additional skills, knowledge, and attitudes that go beyond general creative confidence and centrality. For instance, lower levels of creative self-beliefs in AI settings might stem from whether people find AI tools reliable and trustworthy. With little or no trust in AI-generated output, people may view AI contexts as unsuitable for creative expression. Therefore, it is worth exploring whether higher trust in AI tools and solutions could strengthen the link between general and AI-specific creative self-beliefs, potentially moderating this relationship.

2 The Present Study

This study explored people's creative self-beliefs within the AI contexts and their role in real-life creative engagement: activity and achievement. We had two broad goals for this exploratory study.

First, we were interested in how people's creative self-beliefs when working with AI differ from their general creative self-beliefs. While we expected both to capture the same construct in varied contexts, we predicted that what people think about their creativity within the AI settings might not simply mirror their general creative self-beliefs. Thus, although we anticipated the two to share a significant amount of variance, some distinctiveness was expected. Notably, we considered two opposite directions for these differences equally plausible. On the one hand, the generative potential of AI might provide an “agentic boost”: a person enters a situation with their own creative resources, and the tool can only augment this potential or, at worst, have no effect. On the other hand, overreliance on AI might result in an “agentic slump,” as if discarding human creative initiative in favor of the machine and thus diminishing creative self-beliefs.

Our second goal was to examine the role of AI-specific creative self-beliefs and AI-augmented creative activity in and for creative achievement. Drawing on the Creative Behavior as Agentic Action model (CBAA; Karwowski and Beghetto 2019) and related works (Lebuda et al. 2021), we expected general creative self-beliefs to be associated with achievements both directly and indirectly via increased creative activity. However, an open question is whether the same patterns of relationships describe creativity in AI settings, where strong AI-specific creative self-beliefs make creative activity and achievement more likely. We analyzed these patterns within three creativity domains: text, image, and music production. These domains were chosen due to their substantial reliance on digital technologies, which offer relevant content, functions, and community access (Ceh et al. 2024).

While this study was exploratory, three primary research questions (RQ1–RQ3) drove our endeavors.

RQ1. What is the relationship between creative self-beliefs in general versus AI-specific context? Are people's creative self-beliefs augmented thanks to AI, or do general creative self-beliefs serve as a necessary condition for feeling creative with AI? Furthermore, what role does trust in AI tools and solutions play in the link between general and AI-specific creative self-beliefs? Thus, RQ1 examines the differences between general and AI-specific creative self-beliefs, as well as the correlations and potentially more complex relationships between them (i.e., one serving as a necessary condition of the other or the moderating role of trust in AI). To fully examine RQ1, establishing measurement equivalence (invariance) of creative self-beliefs measures in general and AI-specific contexts is required.

RQ2. What shapes AI-specific creative self-beliefs (AI-CSBs)? What are the roles of personality traits, creative activity with and without AI, trust in AI, and previous creative achievement? Given that AI-CSBs are central to our investigation yet overlooked so far, we decided to set their nomological network by exploring a range of potential predictors, including AI trust, personality traits, creative activity, and achievement (see, e.g., Lebuda et al. 2021).

RQ3. Our final research question concerned the potential role AI-CSBs and AI-augmented creative activity might play in and for creative achievement. Creativity literature provides a compelling case that self-beliefs make activity more likely, thus both directly and indirectly (via activity) influencing creative achievement. While those links are reciprocal (Karwowski and Beghetto 2019; Karwowski, Han, et al. 2019), and activity and achievement influence self-beliefs as well (see RQ2), the causal link self-beliefs–activity–achievement is not only consistent with sociocognitive theorizing (Bandura 1986, 2018) but also empirically established (Karwowski and Beghetto 2019). We know little, however, as to whether these patterns of relationships generalize to the AI contexts. Therefore, our third and final research question focuses on this particular relationship.

3 Method

3.1 Participants

Two hundred seventy-three adults (133 males; 136 females; 2 non-binary; 2 preferred not to report their gender; age: M = 37.61, SD = 11.76) recruited on Prolific participated in this study in December 2023. The sample consisted of people who spoke English as their first language and who reported using any AI-based tools in the past. The data collection was anonymous, and participation was voluntary. Completing the survey took approximately 8 min, and participants were paid £1.25 (GBP 9.36/h) by Prolific. The procedure was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Bologna before the study began.

3.2 Procedure and Measures

The online survey was implemented on the Qualtrics platform. The study began with a question about participants' experience with AI tools. Those who reported never using AI tools were automatically excluded from the subsequent parts of the survey. The remaining participants were then presented with several questionnaires in a fixed order, including measures of creative self-beliefs, creative activity and achievement, trust in AI tools, personality traits, and demographic questions.

3.2.1 Creative Self-Beliefs (CSBs) and AI-Specific Creative Self-Beliefs (AI-CSBs)

Creative self-beliefs were measured with the Short Scale of Creative Self (SSCS; Karwowski et al. 2018), which assesses creative confidence (six items) and creative centrality (five items). The two constructs are often strongly correlated in research (as was observed in the present study: r = 0.68, r = 0.83 for general and AI-specific beliefs, respectively) and are sometimes combined into a higher-order factor (Lebuda et al. 2021; Zielińska et al. 2022). Given our interest in the overall creative self-beliefs, we used the aggregate scores averaged across all 11 items (α = 0.91).

To assess AI-CSBs, we modified the SSCS to reflect people's perceptions of their creative potential while cooperating with the AI tools (11 items, α = 0.94). The same 5-point Likert response scale as in the original scale was used (1 = definitely not, 5 = definitely yes) as well as the same number of items. Before data collection, a pilot test was conducted with 22 participants to ascertain the clarity of the new items and ensure they conveyed the intended meaning. Three participants provided detailed feedback on item comprehension, while the remaining 19 participants completed the questionnaire. Descriptive statistics were analyzed to assess preliminary data distribution, revealing no unusual patterns or issues. Overall, this pilot supported initial content validity and item clarity. The specific items of the existing and new scales are presented in Appendix A (Table A1).

3.2.2 Creative Activities and Achievement

Three subscales of the Inventory of Creative Activities and Achievements (Diedrich et al. 2018) were used to assess participants' engagement in three domains: literature (text production), visual arts (image production), and music (music production). Specifically, we measured: (i) the frequency of creative activities without AI tools (Non-AI Activity: NAI-Activity; α = 0.71, α = 0.73, and α = 0.91 for text, image, and music production respectively; and α = 0.85 calculated across the three domains); (ii) the frequency of creative activities using AI tools (AI-augmented Activity: AIA-Activity; α = 0.71, α = 0.69, and α = 0.82 for text, image, and music production respectively; and α = 0.82 calculated across the three domains); (iii) creative achievement (α = 0.79, α = 0.79, and α = 0.83 for text, image, and music production respectively; and α = 0.85 calculated across the three domains). Participants responded to a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = more than 10 times) to indicate how often they engaged in domain-specific activities over the past year, both with and without artificial intelligence tools. Additionally, they reported their achievements using 11 statements per domain ranging from I have never been engaged in this domain to I have already sold some of my work in this domain. Due to the skewed distribution of creative activities and creative achievement scores across domains, we took the square root of the scores within each domain. We averaged the transformed scores across the three domains to obtain overall creative activities and achievement scores.

3.2.3 AI Trust

Trust in AI was assessed with the TXAI scale by Hoffman et al. (2023), which comprises 8 items (e.g., AI tools are very reliable. I can count on it to be correct all the time; α = 0.77). The original 5-point Likert scale (1 = I agree strongly, 5 = I disagree strongly) was reversed, in line with the other questionnaires in the study, from the negative to the positive pole (1 = I disagree strongly, 5 = I agree strongly).

3.2.4 Personality

The extra-short form of the Big Five Inventory–2 (BFI-2-XS; Soto and John 2017) with 15 items was used to assess the Big Five personality domains: Neuroticism (ω = 0.80), Agreeableness (ω = 0.48), Conscientiousness (ω = 0.72), Extraversion (ω = 0.63), Openness to Experience (ω = 0.62). Participants indicated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the statements on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Disagree strongly; 5 = Agree strongly). We note that the internal consistency of some of the subscales was low, yet this is typical given the instrument's length (Gosling et al. 2003).

The initial examination of the correlations between the study variables revealed considerable overlap between CSBs and Openness (r = 0.73). This appeared to be due to one Openness item, semantically very close to CSBs items: I am someone who is original, comes up with new ideas. Thus, we calculated the Openness scores with this item excluded (ω = 0.48) to make the constructs more distinguishable in the analyses (r = 0.59).

3.3 Data Analysis

All analyses were carried out in R (version 4.3.0) using lavaan (Rosseel 2012), NCA (Dul 2023), and basic R packages. The analysis script and data are available at the Open Science Framework (OSF) Repository: https://osf.io/vkzu6. Given the repeated measurement of creative self-beliefs—regarding general and AI-specific self-views—and our modifications to the AI-related items, we started with ascertaining the measurement invariance, ensuring the construct can be interpreted similarly across both contexts. To address RQ1, we then provided a detailed examination of the relationship between CSBs and AI-CSBs, using the necessary condition analysis (NCA; Dul 2016) and testing the potentially moderating role of AI Trust in this link. We also examined within-person differences in creative self-beliefs between the general and AI-specific contexts. Furthermore, recognizing the likely reciprocal association between creative self-beliefs and creative activity, we explored whether engaging in AIA-Activity explains differences in AI-CSBs above personality, general CSB, AI Trust, and Non-AI Activity (see RQ2).

Finally, we ran two path models to explore the relationships between CSBs, creative activity, and achievement, ultimately controlling for participants' personality characteristics (see RQ3). The indirect effects of CSBs on creative achievement were tested in mediation analysis, using bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals (CIs) obtained with 5000 bootstrap samples to determine the statistical significance.

4 Results

4.1 Measurement Invariance of CSBs and AI-CSBs: Associations and Differences (RQ1)

Given that this study utilized a modified measure of AI-CSBs, we started by examining the invariance of creative self-beliefs measures. Recall that our participants filled out SSCS twice: once regarding their general CSBs and once concerning their AI-CSBs. Therefore, we considered it vital to ensure that the very construct at hand, creative self-beliefs, is measured similarly across the contexts. To this end, we proceeded with measurement invariance analyses in a within-person (longitudinal) version.

In our first step, we estimated the configural invariance model to ensure that the structure of CSBs and AI-CSBs aspects (confidence and centrality) is similar in both cases. As illustrated in Table 1, the configural invariance model was characterized by an acceptable fit in the case of both creative confidence and creative centrality. Our next step involved metric invariance, that is, examining model fit parameters when factor loadings of all items from both CSBs and AI-CSBs scales were constrained to be equal. Such constraints resulted in a relatively large detriment in model fit, as illustrated by ΔCFI and ΔRMSEA (see Table 1). Given that literature provides arguments that partial invariance might be sufficient to estimate correlations between scales and that partial invariance requires at least two items' loadings to be constrained (Byrne et al. 1989), our partial metric invariance model allowed the loadings of four items from confidence scale and three items from centrality scale to differ (i.e., loadings of two items from each scale were constrained to be equal, see our OSF archive for codes). This partial metric invariance model was characterized by acceptable fit based on ΔCFI and ΔRMSEA (comparisons to configural invariance models, see Table 1). While evaluating the changes in model fit, we relied on Chen's (2007) cut-off criteria, that is, we considered models invariant if the difference in CFI (ΔCFI) between constrained and unconstrained models was below 0.010 and the difference in RMSEA (ΔRMSEA) below 0.015.

| Invariance model | CFI/TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creative confidence | |||||

| Configural | 0.950/0.930 | 0.075 (0.055, 0.094) | 0.049 | — | — |

| Metric | 0.910/0.888 | 0.095 (0.078, 0.112) | 0.167 | 0.040 | 0.020 |

| Partial metric | 0.947/0.929 | 0.075 (0.056, 0.094) | 0.070 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Scalar | 0.892/0.867 | 0.103 (0.087, 0.119) | 0.093 | 0.055 | 0.028 |

| Partial scalar | 0.945/0.929 | 0.075 (0.057, 0.093) | 0.068 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Creative centrality | |||||

| Configural | 0.949/0.920 | 0.119 (0.098, 0.139) | 0.086 | — | — |

| Metric | 0.913/0.884 | 0.143 (0.124, 0.162) | 0.140 | 0.036 | 0.024 |

| Partial metric | 0.949/0.926 | 0.114 (0.095, 0.134) | 0.088 | 0.000 | 0.005 |

| Scalar | 0.906/0.879 | 0.146 (0.129, 0.165) | 0.119 | 0.043 | 0.032 |

| Partial scalar | 0.950/0.931 | 0.110 (0.091, 0.130) | 0.089 | 0.001 | 0.004 |

- Note: Measurement invariance testing was based on the criteria indicating non-invariance suggested by Chen (2007): a model was considered invariant if the difference in CFI (ΔCFI) between constrained and unconstrained models was below 0.010 and the difference in RMSEA (ΔRMSEA) below 0.015. The achieved level of invariance according to these criteria is depicted in bold.

- Abbreviations: CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; SRMR, Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index.

The third step involved estimating scalar invariance models, where not only the same structures of the scales were kept (configural invariance) and select loadings constrained (partial metric invariance) but also items' intercepts were assumed equal. Again, both initial models were characterized by significantly worsened fit. However, partial scalar invariance models did not differ notably from partial metric models, thus allowing us to conclude that the models were partially invariant, so correlations and means comparisons between CSBs and AI-CSBs can be reliably estimated.

Our subsequent analyses focused on relationships between CSBs and AI-CSBs and the means comparisons between the two. Given the excellent reliability of our self-beliefs measures (see Methods), all analyses were conducted in a manifest variables framework. Also, as we were interested in general creative self-beliefs, and the confidence and centrality aspects were highly correlated (manifest r = 0.68, r = 0.83, for general and AI-specific beliefs, respectively), we focused on global CSBs variables for a more coherent and concise narration.

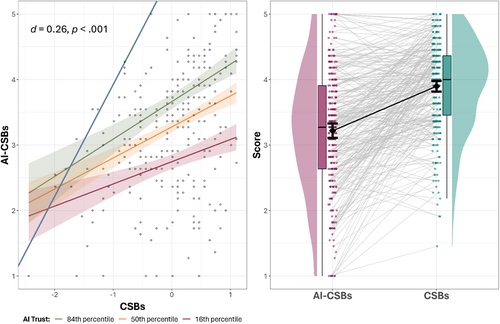

Correlation between CSBs and AI-CSBs, estimated at r = 0.39, was robust and significant, yet indicated a substantial portion of their distinctiveness (see Figure 1, left panel). This link—showing that only about 16% of the variance is shared between the two—calls for a more detailed analysis, the one we provide below. However, responding to our RQ1, it can be concluded that although people's general CSBs are robustly correlated with their AI-CSBs, they are not interchangeable.

Our following analysis revealed that not only were CSBs and AI-CSBs associated, but there was also a sign of a necessary-yet-not-sufficient pattern (see empty upper left corner on the scatter plot on Figure 1, left panel): high levels of AI-CSBs were unlikely when general creative self-beliefs were low. The effect size of this NCA-like pattern, estimated at d = 0.26, was moderate, as per Dul's recommendations (Dul 2016). Thus, people who do not believe in their creative abilities or consider them irrelevant are unlikely to feel differently in AI settings.

Additionally, the link between CSBs and AI-CSBs was moderated by AI trust (see scatterplot in Figure 1): CSBs were more strongly related to AI-CSBs among people who trusted AI tools more (the CSBs × AI Trust interaction effect: β = 0.09, p = 0.039). However, as indicated by a simple slope analysis, the link between CSBs and AI-CSBs remained significant among people who did not trust (16th percentile; b = 0.34, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001), moderately trusted (50th percentile; b = 0.47, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001), or highly trusted AI (84th percentile; b = 0.57, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001).

Our next question was whether people's creative self-beliefs are augmented thanks to AI. Thus, we compared the average levels of CSBs and AI-CSBs and found a significant, moderate-to-large difference between the two (Figure 1, right panel), t(272) = 12.37, p < 0.001, d = 0.75 [0.61, 0.88]. Therefore, contrary to what could be expected (see our RQ1), people's perceptions of their creative potential when accompanied by AI are lower compared to their general CSBs.

4.2 Exploring the Correlates of Creative Self-Beliefs (RQ2)

Correlations among the key study variables are presented in Table 2. Whereas general CSBs were significantly related to creative achievement, this was not the case for AI-CSBs. Moreover, general CSBs were related to creative activities performed with and without AI, while AI-CSBs displayed significant links only with AIA-Activities. The structure of correlates among personality traits was consistent across CSBs and AI-CSBs, with a notable difference being the link with Openness: very high for CSBs (r = 0.59) and null for AI-CSBs (r = 0.02).

| Variable | M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CSBs | 3.90 | 0.68 | — | |||||||||

| 2. AI-CSBs | 3.22 | 0.92 | 0.39 | — | ||||||||

| 3. AI trust | 3.16 | 0.65 | 0.10 | 0.59 | — | |||||||

| 4. NAI-activity | 1.38 | 0.24 | 0.40 | 0.07 | −0.04 | — | ||||||

| 5. AIA-activity | 1.15 | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.36 | — | |||||

| 6. Achievement | 1.75 | 1.35 | 0.46 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.59 | 0.39 | — | ||||

| 7. Openness | 3.81 | 0.93 | 0.59 | 0.02 | −0.10 | 0.32 | 0.09 | 0.46 | — | |||

| 8. Conscientiousness | 3.56 | 0.89 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.02 | −0.05 | −0.05 | 0.05 | — | ||

| 9. Extraversion | 2.85 | 0.87 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.34 | — | |

| 10. Agreeableness | 3.82 | 0.76 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.10 | — |

| 11. Emotional stability | 3.09 | 1.11 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.23 |

- Note: Bolded coefficients are statistically significant with α = 0.05. Creative activities and creative achievements scores were square rooted due to their skewed distribution.

- Abbreviations: AIA-activity, AI-augmented activity; AI-CSBs, AI-specific creative self-beliefs; CSBs, creative self-beliefs; NAI-activity, non-AI activity.

What drives AI-CSBs? Given the necessary-yet-not-sufficient pattern of relationship between CSBs and AI-CSBs, and the theorized reciprocal relationships between creative self-beliefs and creative activity (in line with previous studies; e.g., Tierney and Farmer 2002), we were interested in whether engaging in AIA-Activities does indeed explain the differences in AI-CSBs beyond CSBs, AI Trust, and NAI-Activities, controlling for personality characteristics. Should this effect be observed, it would suggest that people might shape their AI-specific beliefs based on hands-on experience with AI. While this interpretation is theoretically sound (see, e.g., Bandura 1986), we emphasize the tentative nature of any conclusions due to the correlational nature of our study.

To test this reasoning, we used hierarchical regression with AI-CSBs regressed on the variables of interest entered into the model in six blocks (Table 3). Among the personality traits, Extraversion and Agreeableness significantly yet weakly predicted AI-CSBs in the first step (R2 = 9%). General CSBs (ΔR2 = 16%) and AI Trust (ΔR2 = 24%) incrementally added to the variance explained. Importantly, while the NAI-Activities did not contribute to explaining the differences in AI-CSBs (ΔR2 = 0), the AIA-Activities significantly predicted AI-CSBs beyond the remaining variables (ΔR2 = 3%). The achievements the participants reported were added in the last step but found unrelated to AI-CSBs (ΔR2 = 1%).

| Variable | AI-specific creative self-beliefs | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | p | B | SE | β | p | B | SE | β | p | B | SE | β | p | B | SE | β | p | B | SE | β | p | |

| Intercept | 1.56 | 0.37 | 0.00 | < 0.001 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.203 | −1.13 | 0.34 | 0.00 | 0.001 | −0.99 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.009 | −1.67 | 0.40 | 0.00 | < 0.001 | −2.02 | 0.44 | 0.00 | < 0.001 |

| O | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.690 | −0.30 | 0.06 | −0.31 | < 0.001 | −0.19 | 0.05 | −0.19 | 0.001 | −0.19 | 0.05 | −0.19 | 0.001 | −0.17 | 0.05 | −0.17 | 0.001 | −0.15 | 0.05 | −0.15 | 0.008 |

| C | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.175 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.696 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.728 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.674 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.798 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.866 |

| E | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.002 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.068 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.153 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.124 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.226 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.215 |

| A | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.003 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.007 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.030 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.032 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.025 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.024 |

| ES | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.886 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.506 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.817 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.844 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.882 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.790 |

| CSBs | 0.69 | 0.09 | 0.51 | < 0.001 | 0.56 | 0.08 | 0.42 | < 0.001 | 0.58 | 0.08 | 0.43 | < 0.001 | 0.54 | 0.08 | 0.40 | < 0.001 | 0.56 | 0.08 | 0.41 | < 0.001 | ||||

| AI trust | 0.73 | 0.07 | 0.51 | < 0.001 | 0.72 | 0.07 | 0.51 | < 0.001 | 0.63 | 0.07 | 0.45 | < 0.001 | 0.62 | 0.07 | 0.44 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| NAI-act | −0.16 | 0.19 | −0.04 | 0.400 | −0.41 | 0.19 | −0.11 | 0.033 | −0.25 | 0.21 | −0.06 | 0.242 | ||||||||||||

| AIA-act | 1.16 | 0.27 | 0.21 | < 0.001 | 1.29 | 0.28 | 0.23 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| ACH | −0.08 | 0.04 | −0.11 | 0.061 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| N | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 | ||||||||||||||||||

| R2/R2adjusted | 0.104/0.088 | 0.261/0.244 | 0.494/0.481 | 0.495/0.480 | 0.528/0.511 | 0.534/0.516 | ||||||||||||||||||

| AIC | 711.118 | 660.613 | 559.227 | 560.495 | 544.533 | 542.868 | ||||||||||||||||||

| ΔR2 | 0.157 | 0.236 | −0.001 | 0.031 | 0.005 | |||||||||||||||||||

| F | F(1,266) = 56.41, p < 0.001 | F(1,265) = 122.00, p < 0.001 | F(1,264) = 0.71, p = 0.400 | F(1,263) = 17.89, p < 0.001 | F(1,262) = 3.54, p = 0.061 | |||||||||||||||||||

- Note: Significant effects are bolded for readability.

- Abbreviations: A, agreeableness; ACH, achievement; AIA-act, AI-augmented activity; C, conscientiousness; CSBs, creative self-beliefs; ES, emotional stability; E, extraversion; NAI-act, non-AI activity; O, openness.

4.3 The Paths Toward Creative Achievement (RQ3)

Previous research found creative self-beliefs indirectly associated with creative achievement through increased creative activity (Lebuda et al. 2021). Is this also the case for AI-CSBs? To address this, we ran a path model testing how creative self-views predict creative activity and achievement across domains1.

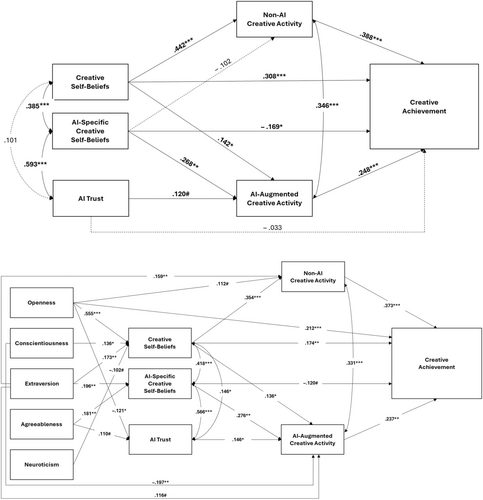

As shown in Figure 2 (upper panel), CSBs predicted creative achievement both directly and indirectly: via enhanced NAI-Activity (indirect effect: b = 0.34, 95% CI [0.21, 0.50], p < 0.001) and AIA-Activity (indirect effect: b = 0.07, 95% CI [0.02, 0.13], p = 0.026). However, AI-CSBs translated into a greater achievement only indirectly, through a higher creative activity with AI (b = 0.10, 95% CI [0.03, 0.19], p = 0.022). Interestingly, the direct effect of AI-CSBs—when not mediated by activity with AI—was negative, suggesting its potentially harmful effects on achievement. The link between AI Trust and AIA-Activity was marginally insignificant when controlling for AI-CSBs.

Next, we tested the effects of creative self-beliefs on creative activity and achievement, accounting for participants' personality (see Figure 2, lower panel). The model demonstrated the varied structure of predictors of CSBs and AI-CSBs among personality traits. While CSBs were positively associated with Openness (β = 0.56, p < 0.001), Extraversion (β = 0.17, p = 0.004), and Conscientiousness (β = 0.14, p = 0.015), AI-CSBs were positively linked to Extraversion (β = 0.20, p = 0.002), and Agreeableness (β = 0.18, p = 0.005). Additionally, AI Trust was negatively associated with Openness (β = −0.12, p = 0.044).

The results for the creative self-beliefs—activity—achievement relationships observed in a simpler model essentially held when controlling for personality traits, and in most cases, the analyzed links only slightly decreased. CSBs predicted NAI-activity (β = 0.35, p < 0.001), which was further associated with a greater achievement (β = 0.37, p < 0.001). This yielded a significant and positive indirect effect (b = 0.26, 95% CI [0.14, 0.42], p < 0.001). Moreover, with the significant links with AIA-Activity (β = 0.14, p = 0.039), CSBs predicted creative achievement also via enhanced creative activity undertaken with AI support (marginally insignificant indirect effect: b = 0.06, 95% CI [0.00, 0.15], p = 0.081), replicating the results from a simpler model. The direct effect of CSBs on achievement remained significant (β = 0.17, p = 0.009).

AI-CSBs were related to AIA-Activity (β = 0.28, p = 0.001), while the latter was associated with creative achievement (β = 0.24, p = 0.001), yielding a significant indirect effect (b = 0.10, 95% CI [0.02, 0.18], p = 0.016). When we controlled for personality and activity, the negative direct link of AI-CSBs on achievement remained marginally insignificant (β = −0.12, p = 0.058). Additionally, there was a small yet significant association between AI Trust and AIA-Activity (β = 0.13, p = 0.038).

Among the personality traits, Openness predicted creative achievement (β = 0.21, p < 0.001), though its link with NAI-activity was marginally insignificant (β = 0.11, p = 0.089). Extraversion was associated with NAI-activity (β = 0.16, p = 0.004), yet showed a marginally insignificant link to AIA-Activity (β = 0.12, p = 0.054). Conscientiousness negatively correlated with AIA-Activity (β = −0.20, p = 0.005).

One puzzling yet persistent finding across both models was the negative direct link of AI-CSBs on achievement when controlling for the other variables of interest. Given the insignificant zero-order correlation between the two (rAI-CSBs–Achievement = 0.05, p = 0.370), the suppression was apparent (Paulhus et al. 2004). To unpack this, we ran a hierarchical regression with achievement regressed on AI-CSBs, general CSBs, and AIA-Activity introduced to the model one at a time. When general CSBs were added, AI-CSBs—a predictor composed almost entirely of variance irrelevant to the dependent variable—started to show negative links with achievement (β = −0.14, p = 0.013), while the regression weight for the CSBs increased from the initial rCSBs–Achievement = 0.46, p < 0.001 to β = 0.52, p < 0.001. Introducing AIA-Activity to the model further emphasized these tendencies, with AI-CSBs predicting achievement at β = −0.28, p < 0.001. Although such effects often suggest statistical artifacts of multicollinearity, the moderate links among predictors call against this explanation. Instead, the observed suppression pattern indicates that after removing the overlapping variance with CSBs, the cleansed AI-CSBs negatively predict achievement. We suggest a more substantive explanation for this effect in the Discussion section.

5 Discussion

The public release of generative AI tools has ignited an open debate on their potential impacts across various aspects of human functioning. Opinions vary widely, with AI enthusiasts heralding these tools as revolutionary while skeptics raise existential concerns about AI as a threat to humankind (Fast and Horvitz 2017). This divergence has sparked various scenarios predicting how human-AI coexistence might evolve, with the creativity field being no exception here (Benbya et al. 2024; Vinchon et al. 2023; Watkins and Barak-Medina 2024). Key to these scenarios is the trade-off between human and AI agentic contributions to the creative process, ranging from views of AI as an assistant or a tool that augments human creativity to a partner contributing “co-agently,” or even as an autonomous creative agent operating with no or minimal human engagement. Thus, a critical yet neglected factor that might shape and be shaped by human-AI interactions is people's perception of their creative abilities, a key component of creative agency (Beghetto and Karwowski 2023, in press).

In this exploratory study, we empirically disentangled general creative self-beliefs from AI-specific creative self-beliefs, which consider the AI contexts for manifesting creative abilities. Our reasoning assumed that people's views on creativity when working with AI might differ from their general creative self-beliefs. While expecting a positive relationship between the two seemed reasonable, we were interested in whether interactions with AI empower or rather detriment creative self-beliefs. This study aimed to explore the complex links between general and AI-specific creative self-beliefs and their within-person differences.

While personal experiences and the effects produced through one's actions are vital sources of people's self-beliefs (Bandura 1986), these beliefs further inform whether and how a person decides to act (Bandura 2018; Sternberg 2003). In the creativity literature, this assertion has been emphasized in the CBAA model (Karwowski and Beghetto 2019) and found empirical support (Chen 2016; Qiang et al. 2020; Zielińska et al. 2024). The current study applied this logic in AI settings, examining whether creative self-beliefs predict AI-assisted creative engagement. We distinguished between creative activities in AI-augmented and non-AI contexts to effectively capture the context-specific nature of the proposed mechanisms. Although the cross-sectional design of our study does not provide convincing evidence of causal effects, it represents the first empirical attempt to explore the role of people's creative self-beliefs in real-life creativity—creative activity and achievement—within AI contexts. In what follows, we overview these promising, albeit initial, findings and provide some considerations for future research.

5.1 General and AI-Specific Creative Self-Beliefs: The Same or Different?

Our study demonstrated a positive and robust relationship between general and AI-specific creative self-beliefs (manifest correlation estimated at r = 0.39). However, this link does not imply that these self-views are interchangeable. Rather, what people think about their creative potential while working with AI does not merely reflect what they think about their creativity in general. Further analysis revealed that people with low general creative self-beliefs are unlikely to hold high AI-specific creative self-beliefs. Suppose people do not consider themselves creative in general. In that case, the chances are low that they will think about themselves differently in AI settings.

On the other hand, having strong general creative self-beliefs does not guarantee that one will feel creative when working with AI. One factor we considered relevant in further untangling this relationship is AI Trust. Even if people are confident in their creative abilities, they might not maintain this conviction in AI contexts due to a lack of trust in these tools. Skepticism about their reliability, predictability, and overall usefulness can negatively affect how one perceives their creative potential when using AI. This perspective suggests a more externalized view, where AI is seen as inefficient for creative purposes, leading one to consider AI unsuitable in the context of creativity. In such cases, AI tools can suppress one's creative potential. Thus, we considered AI Trust as a moderator of the link between general and AI-specific creative self-beliefs, expecting those low in AI Trust to show a less consistent relationship between the two. This was indeed the case. However, although weaker, this link was still significant and positive even among participants with limited trust in AI tools. This corroborates the idea of general self-beliefs as a necessary factor for AI-specific self-beliefs, with the link being positive and significant even for those who do not consider AI a reliable tool. Essentially, even minimal trust in AI cannot make a creatively confident person completely undermine their creative abilities in AI contexts.

Given the findings discussed so far, it is unsurprising that people hold higher general than AI-specific creative self-beliefs. The differences observed were apparent, estimated at Cohen's d = 0.75. Whether this is due to the expected challenges in using AI efficiently or the fear of diminished authenticity in one's creative output when working with AI (“Would it still be me and my work?”) remains a question for future research. Nevertheless, while previous studies have primarily focused on how AI-assistance affects human creative performance (Jia et al. 2024; Urban et al. 2024; Zhou and Lee 2024), our investigation adds to the discussion by highlighting motivational aspects of interaction with AI, revealing its “anti-agentic side”: people feel more creative on their own rather than with AI.

What factors could possibly narrow this gap? One key element might be people's hands-on experience with AI, especially participation in AI-supported creative activities. In fact, the observed links between AI-specific creative self-beliefs and AI-augmented activity were sound, echoing the well-replicated association between general creative self-beliefs and creative activity (Lebuda et al. 2021). While self-beliefs are often considered a motivational trigger for creative actions (Karwowski and Beghetto 2019), the relationship is reciprocal: engaging in creative action might also influence creative self-beliefs. Thus, in the specific context of AI, creative self-beliefs might both impact and be impacted by AI-assisted creative actions. This prompted us to explore whether engaging in AI-augmented activities explains differences in AI-specific creative self-beliefs.

Considering the necessary yet not sufficient role of general creative self-beliefs and the robust links with AI Trust, one could argue that AI-specific creative self-beliefs might be an epiphenomenon of these two factors. However, our findings suggest otherwise: AI-augmented creative activity predicts AI-specific creative self-beliefs even when controlling for personality, general creative self-beliefs, and non-AI creative activity. This points to the distinctiveness of AI-specific creative self-beliefs and hints at a potential learning-based mechanism where people develop or recalibrate their AI-specific creative self-beliefs based on their creative experiences with AI. Therefore, our results suggest that people's perceptions of AI as enhancing their creativity might not solely reflect their general creative self-beliefs, trust in AI, or personality characteristics but may also be shaped by specific interactions with AI during creative tasks. This interpretation is consistent with the previous study (Tang et al. 2024), but we suggest testing it with more robust research designs.

The distinctiveness between general and AI-specific creative self-beliefs is further emphasized when looking at their personality predictors. In the case of general creative self-beliefs, the effects we observed echoed those already demonstrated in the literature (Karwowski and Lebuda 2016), with the most robust links observed for Openness, followed by Extraversion and Conscientiousness. In contrast, AI-specific creative self-beliefs were predicted only by Extraversion and Agreeableness. This result is intriguing, given that Extraversion and Agreeableness are systematically shown to be the most relevant personality characteristics for interpersonal behavior (Tov et al. 2016). This could imply that human-AI interaction in creative contexts mimics interpersonal communication (or at least its perception) in certain ways, resulting in similar personal tendencies conducive to engagement in this kind of interaction. Thus, people who seek gratification from outside the self and are generally trustful (i.e., more extroverted) and capable of cooperation and compliance (i.e., more agreeable) tend to have a more positive perception of interacting with AI within creative settings.

5.2 Do AI-Specific Creative Self-Beliefs Matter for Real-Life Creativity?

The important question this study addressed was whether holding high AI-specific creative self-beliefs might benefit real-life creativity: spur creative engagement and make creative achievement more likely. Drawing on existing research that shows creative activity is a necessary condition for achievement (Zielińska et al. 2023) and that the link between creative self-beliefs and achievement is mediated by creative activity (Lebuda et al. 2021), we tested similar mediation mechanisms within AI creative contexts.

Replicating previous research (Lebuda et al. 2021), we found that general creative self-beliefs predict creative achievement through more intense engagement in creative activity; people confident in their creative abilities and seeing value in creative functioning undertake creative activities more frequently and have a greater chance to translate their efforts into achievement. Yet, contrary to previous investigations, our study demonstrated direct links between general creative self-beliefs and achievement, even when personality characteristics were controlled. This suggests additional features of the creative self-beliefs—achievement link not necessarily captured in the model tested. These might include mediating behaviors (e.g., through increased self-regulatory efforts, see Zielińska et al. 2024) or moderating environmental factors (see, e.g., Benedek 2024).

Our path models revealed an intriguing yet weak, negative direct link between AI-specific creative self-beliefs and creative achievement. The initially insignificant association between the two, although positively signed, turned negative after accounting for general creative self-beliefs. We see this effect as having an interesting, albeit speculative, meaning. Consider how general and AI-specific creative self-beliefs can be interpreted after removing their shared variance in multivariate models. For general self-beliefs, this might indicate a conviction in one's creative abilities within non-AI contexts of creative functioning. In contrast, the unique component of AI-specific creative self-beliefs would instead represent a very strongly AI-oriented conviction, likely attributing the creative ability to AI tools. Indeed, AI-specific creative self-beliefs seem to encompass both self-oriented (e.g., “I am creative”) and AI-oriented (e.g., “AI is creative”) beliefs. Thus, when cleansed of the shared variance with self-oriented conviction, AI-specific creative self-beliefs might represent an attitude that delegates creative initiative to AI, expecting it to be creative on its own rather than augmenting a person's creativity. The detrimental effect on agency of interacting with AI may once again be at play. We emphasize the tentativeness of this interpretation, which warrants further testing in future studies, especially given the potential practical implications of this observation. In essence, overreliance on or misplaced belief in AI's autonomous creative ability—instead of putting in one's own creative efforts—can be detrimental to human creative achievement.

5.3 Limitations

The current study has raised several questions regarding the role of creative self-beliefs in creative activity and achievement within and without AI-assisted contexts. However, more work is necessary to replicate and extend these findings. The most critical limitation of our investigation is the cross-sectional design, which naturally casts doubt on any causal claims. Longitudinal and experimental studies are needed to better understand the mutual influences between creative action and creative self-beliefs.

Also, the complex findings related to the role of AI-specific creative self-beliefs in creative achievement require further investigation. Unlike creative activity, we did not differentiate creative achievements between those obtained from works and performances generated with or without AI assistance. This decision was made because it seemed premature to discuss creative achievement with AI, as the data were collected in December 2023, when people began using AI tools more widely. However, using context-specific beliefs to explain general creative achievements might misalign the conceptual frameworks, potentially limiting the self-beliefs' predictive validity. Thus, while the proposed suppression-based interpretation seems plausible, focusing on the observed indirect effect might be more informative at this stage. Specifically, we found that AI-specific creative self-beliefs positively predict creative achievement through increased engagement in activities where those beliefs are indeed relevant (i.e., AI-augmented activities).

5.4 Conclusion

This exploratory research highlights the complexities of the creative self-beliefs—activity—achievement relationships within AI contexts of creative action. Despite our AI-focused perspective, the insights offered are remarkably humanistic (Corazza 2019). The possibilities provided by AI tools do not necessarily make people feel more creative; they seem to feel more creative on their own. Moreover, for those lacking confidence in their creative resources, the prospect of interacting with AI does not act as an agentic cure. Instead, strong personal creative self-beliefs are necessary for feeling empowered during interactions with AI. Notably, the contributions of AI-specific creative self-beliefs to real-life creativity might be twofold: they can either encourage one to incorporate AI tools into their creative endeavors, making creative achievements more likely, or they can provoke a reactionary, detrimental effect on human agency that impedes creative efforts and hinders creative attainments. We hope future studies will build on these findings by employing more dynamic, experimental approaches to better understand the agentic (ex)changes that occur during human–AI creative interactions.

Acknowledgments

Giovanni Emanuele Corazza and Angela Faiella acknowledge financial support by National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.1, Call for tender No. 104 published on 02.02.2022 by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR), funded by the European Union - Next generationEU - Project Title - DA VINCI. In Da Vinci’s mind: Fundamental Correlates of Creativity for Artists and Scientists - CUP J53D2300799 0001- Grant Assignment Decree No. 0001016, adopted on 07.07.2023 by the Italian Ministry of Ministry of University and Research (MUR). Maciej Karwowski was supported by a grant from the National Science Centre, Poland (grant number 2022/45/B/HS6/00372). Open access publishing facilitated by Universita degli Studi di Bologna, as part of the Wiley - CRUI-CARE agreement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Endnotes

Appendix A

| Creative self-beliefsa | AI-specific creative self-beliefsb |

|---|---|

| I think I am a creative person | With the aid of AI tools, I think I am a creative person |

| My creativity is important for who I am | My AI-based creativity is important for who I am |

| I know I can efficiently solve even complicated problems | I know I can efficiently solve even complicated problems with the aid of AI tools |

| I trust my creative abilities | I trust my AI-augmented creative abilities |

| My imagination and ingenuity distinguishes me from my friends | My imagination and ingenuity in AI prompting distinguishes me from my friends |

| Many times I have proved that I can cope with difficult situations | Many times I have proved that I can cope with difficult situations through AI |

| Being a creative person is important to me | Being a creative person is important to me, even with AI |

| I am sure I can deal with problems requiring creative thinking | I am sure I can deal with problems requiring creative thinking with the help of AI |

| I am good at proposing original solutions to problems | Using AI, I am good at proposing original solutions to problems |

| Creativity is an important part of myself | Creativity is an important part of my cyberhuman-self |

| Ingenuity is a characteristic that is important to me | Ingenuity is a characteristic that is important to me as a cyberhuman creative |

- a Original questionnaire from Karwowski et al. (2018).

- b Modified questionnaire.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Analysis script and data are available at the Open Science Framework (OSF) Repository https://osf.io/vkzu6.