Association Between the Creative Experience of Haiku Poetry and a Tendency Toward Self-Transcendent Emotions

We would like to thank Editage (http://www.editage.com) for editing and reviewing this manuscript for English language.

ABSTRACT

Haiku is the world's shortest form of poetry, describing nature and ordinary everyday life. Previous studies and quotes from professional haiku poets suggest that haiku can foster self-transcendent emotions, such as gratitude and awe. This study compares how those who did and did not create at least one haiku in the past month experience self-transcendent emotions. A total of 192 haiku writers and 177 non-writers responded to scales related to self-transcendent emotions, such as gratitude for serenity, gratitude trait, and trait awe. The results of the Bayesian implementation of Generalized Linear Mixed models revealed that haiku writing increased the frequency of gratitude for serenity and awe, rather than general gratitude. These effects persisted even after controlling for interest in art and educational level, indicating that haiku writing has unique characteristics, including encouragement of attention to nature and a different perspective on daily life. Even in the absence of special events, a change in perspective toward everyday life occurs through creating haiku, and people appreciate and feel awe toward ordinary, everyday things. These novel findings contribute to the study of creativity and emotion.

HAIKU POETRY

Haiku is one of the world's shortest poetic genres, using the formula 5-7-5 mora (Niikuni, Wang, Makuuchi, Koizumi, & Kiyama, 2022). A haiku must contain a single seasonal word, and attention to nature before and during its creation is necessary (Rillero, 1999). Haiku originated from Haikai—humorous short poems that focus on everyday life; moreover, they reflect nature and a different view of common, everyday events (Shirane, 2023). These rules and styles may cause haiku writers to view the world differently from non-writers. Specifically, they love nature and pay attention to events that non-writers may overlook. Haiku writers are assumed to develop unique personalities or emotional traits through this repeated process of creation. Indeed, haiku writing influences creativity (Stephenson & Rosen, 2015) and attitudes toward ambiguity (Hitsuwari & Nomura, 2023). According to Stephenson and Rosen (2015), 20 min of haiku writing (vs. story writing) per day for 3 days resulted in increased creativity when writing about nature or negative subjects. Hitsuwari and Nomura (2023) determined that the group that wrote haiku for 20 min showed a lower tendency toward absolutism (a subscale of attitude toward ambiguity and an attitude of eliminating ambiguity and seeking only the correct answer). Although haiku writing has a psychological impact, no study has examined the psychological effects of habitual haiku creation. Several people regularly create haiku, and the habitual effects could be greater than the effects of less frequent interventions, as shown in previous studies. In this study, we thus examined the psychological effects of daily haiku writing, focusing on self-transcendent emotions, which are previously known to be associated with haiku poetry.

SELF-TRANSCENDENT EMOTIONS

Self-transcendent emotions, such as gratitude and awe, transcend an individual's temporal needs and self-interest and result in concern and care for others, including animals and natural beings (Stellar et al., 2017). Gratitude has been operationally defined as the recognition that one has benefited from a valuable and intentional voluntary action of another (McCullough, Kilpatrick, Emmons, & Larson, 2001). Awe arises from the perception of vastness and the need for accommodation (Keltner & Haidt, 2003). Such self-transcendent emotions are associated with attention and care for society and nature, rather than care of self. For instance, reading stories that evoked gratitude (vs. entertainment and boredom) was associated with nature through the mediation of positive feelings of self-transcendence (Chen, Liu, Fu, Guo, & Chen, 2022). Another study showed that people who are more likely to experience self-transcendent emotions, such as awe and compassion, are more likely to feel connected to nature and engage in altruistic and conservation behaviors (Jacobs & McConnell, 2022).

Considering that haiku are written about nature and sometimes imply universal laws of nature,1 it is reasonable to assume that haiku writing and self-transcendent emotions are related and that daily haiku writing transforms the way self-transcendent emotions are experienced. Indeed, individuals who are more likely to feel awe are known to appreciate the beauty of haikus (Hitsuwari & Nomura, 2022). Although the relationship between haiku and gratitude has not been examined in prior literature, haiku poet Tokuro Kogure states, “When I started writing haiku, I became aware of myself as a part of the great nature. Since then, I have come to appreciate everything” (Kogure, 2015). This suggests that haiku writing increases experiences of gratitude. In general, gratitude arises from recognizing that one has benefited from valuable, intentional, and voluntary actions (McCullough et al., 2001). However, as nature constantly provides people with value such as sunlight, rain, and plants, feelings of gratitude can arise even when no specific significant event has occurred. Such gratitude, unrelated to a specific event, has been termed “gratitude for serenity” (Kuranaga & Higuchi, 2013). Considering that haiku writing, in addition to nature, can refer to trivial everyday events and elevate them to art forms, gratitude for serenity is likely enhanced by haiku writing. Although the relationship between self-transcendent emotions and haiku is known or indicated in various aspects, including in appreciation studies, haiku creation and self-transcendent emotions have not been investigated. Therefore, this study examined the psychological effects of everyday haiku writing by comparing how haiku writers and non-writers perceive self-transcendent emotions.

AIMS

Several studies have examined the effects of haiku on psychological states, including self-transcendent emotions; however, none have examined these effects for daily haiku writers. Therefore, we investigated the differences in haiku writers' and non-writers' perceptions of their emotions, namely the relationship between haiku writing and self-transcendent emotions such as gratitude and awe. Two main hypotheses are as follows: First, haiku writers feel more gratitude, especially gratitude for serenity because haikus include seasonal words and must be written with awareness of nature, time of year, and so on, leading to self-transcendence and gratitude for serenity even in the absence of a significant event. Second, haiku writers feel more awe than non-writers. This extends the results of a previous study on haiku appreciation to haiku writing. We also explored the relationship between haiku writing and other psychological factors such as spirituality, mindfulness, nostalgia, religiosity, and life satisfaction. These measures were chosen because: (a) individuals with higher tendencies toward these measures have been reported to have a higher aesthetic appreciation of haiku (Hitsuwari & Nomura, 2022) and (b) these factors are thought to be closely related to self-transcendent emotions. This study shows that individual traits are associated with self-transcendent emotions and can be enhanced by an ecologically valid method of haiku writing. The results contribute to the understanding of self-transcendent emotions and the development of education and culture.

METHOD

This study was conducted as per the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kanazawa Institute of Technology. All methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations. We obtained informed consent from the participants by asking them to press the “I agree” button on a screen containing a survey summary. The Appendix S1, questions, data, Qualtrics Project, and R scripts used in this study are available online (https://osf.io/u4fdp/).

PARTICIPANTS

The study comprised 197 participants who had written at least one haiku in the past month2 and 199 who had not. Participants were recruited in February 2023 using a survey on the Japanese Yahoo! Crowdsourcing platform (https://crowdsourcing.yahoo.co.jp).

PROCEDURE

Participants accessed and completed the “Psychological Survey of Haiku Experience” questionnaire created by Qualtrics (https://www.qualtrics.com/jp). Haiku writers were asked to indicate the number of haikus they had written in the past month, frequency of writing haikus, their experience of submitting haikus to magazines and contests, and the places where they normally write haikus. Non-writers were surveyed on how much they had been exposed to haikus as adults. All participants subsequently completed the Self-Transcendent Emotion Scale, which included the frequency of gratitude for serenity (Kuranaga, Fukuda, & Aikawa, 2024), the gratitude trait scale (Shiraki & Igarashi, 2014), and trait awe (Shiota, Keltner, & John, 2006). These scales measure personalities, such as the frequency of daily feelings of self-transcendence. We believe that these personalities are consistent with the variable that was the target of this study, the sense of self-transcendence in Japanese people's daily lives. Additionally, participants completed measures related to self-transcendent emotions such as life satisfaction (Oishi, 2009), tendency for nostalgia (Routledge, Arndt, Sedikides, & Wildschut, 2008), spirituality (Higa, 2002), mindfulness (Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire short; Takahashi, Saito, Fujino, Sato, & Kumano, 2022), and the religious factor of value orientation (Sakai & Hisano, 1997; see also Appendix S1). Then, they responded to questions about their interest in art (Hitsuwari, Ueda, Yun, & Nomura, 2023). Finally, they responded with their gender, age, and highest education level.

MEASURES

Gratitude for serenity

Participants responded on how frequently they experienced gratitude for serenity (Kuranaga et al., 2024) through five items (e.g., waking up in the morning as usual). Response options ranged from 1 (I rarely feel gratitude) to 7 (I experience gratitude quite often). They also had the option to respond with 8 (I do not meet this circumstance or have never experienced this circumstance). Kuranaga et al. (2024) established the validity and reliability of these measures.

Gratitude traits

The Japanese translation of the Gratitude Questionnaire-Six-Item Form (McCullough, Emmons, & Tsang, 2002; Shiraki & Igarashi, 2014), a five-item seven-point Likert scale, was used. The questionnaire measures the tendency to express and experience gratitude. Shiraki and Igarashi (2014) ascertained the validity and reliability of these measures.

Awe

The awe subscale of the six-item, seven-point Likert Dispositional Positive Emotions Scale (Shiota et al., 2006) was used. Many studies in Japan frequently use this scale to measure awe traits. Given its high reliability and validity, we used it for this study. An example item is, “I often feel a sense of awe.”

Interest in and experience with art in general

Similar to Hitsuwari et al. (2023), participants were asked the following three items about their experience with creative work, interest in art, and frequency of exposure to art: “If you have experience in creative work (e.g., as a designer or writer) or in creating something, please indicate how much experience you have had?” “To what extent are you interested in the arts?” and “How often do you go to museums or art galleries?”

RESULTS

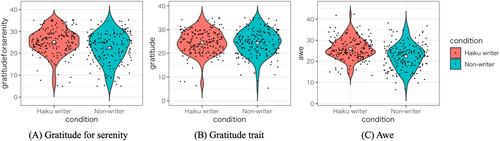

The excluded participants from the analysis of this study are as follows. We defined haiku writers as respondents who had written at least one haiku in the past month; thus, our analysis excluded the five respondents who answered that they had not written any haiku in the past month in the response item on the frequency of writing haiku. We also excluded nine participants who answered that they wrote haiku every day from non-writers because we defined respondents who did not write haiku as non-writers. In addition, 13 who answered the item on the Directed Questions Scale (“For this item, choose 2.”) incorrectly were excluded from the analysis because they were considered inappropriate responses in the other items as well. Consequently, 369 participants, including 192 haiku writers (124 men, one other; M age = 44.57, SD age = 11.35; range 19–77) and 177 non-writers (124 men; M age = 48.60, SD age = 10.86; range 22–75) were analyzed.3 Figure 1 shows the violin plots of haiku writers and non-writers for gratitude for serenity, gratitude, and awe.

For all analyses reported below, the following Bayesian generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) were performed. The use of GLMM allows for the addition of random effects that represent individual differences among respondents. The advantages of Bayesian estimation for parameter estimation are as follows. Bayesian estimation assumes a probability distribution for parameters. Therefore, we can calculate confidence intervals for parameters directly. Hence, interpreting the results is more intuitive than conventional analysis methods, which often estimate parameters as constants. Moreover, it avoids the problem of over-learning that is typical in the maximum likelihood method.

Our model used a dummy variable for haiku writers (0: non-writer, 1: writer) as a fixed effect and interest in art in general, age, and years of education as control variables. Age was added as a control variable, as gratitude is higher among older adults (Chopik, Newton, Ryan, Kashdan, & Jarden, 2019). For the highest education level, we replaced the respondent's choice with the years of education. Interaction effects were not included in the model. We employed a uniform distribution as a sufficiently broad prior distribution within the range that the parameters can take. The first reason is that fixed effects in GLMM are global parameters. Second, there is no previous study that we could use as a direct reference for the prior distribution of the parameters in this study. A non-informative distribution is frequently used in such a case. However, since we can use other distributions as the prior distribution, the results in this paper were based on a model in which the uniform distribution with no information is the prior distribution.

The posterior distribution of each parameter was Bayesian and estimated in a GLMM, with the random intercept effect of participants as a random effect. The results were analyzed in R (4.3.1) using the brms package (Bürkner, 2017). A normal distribution was fitted for the response variable and a random intercept effect for participants. All iterations were set to 15,000, burn-in samples were set to 2,500, and the number of chains was set to four.

GRATITUDE AMONG HAIKU WRITERS VS. NON-WRITERS

In the analysis of gratitude for serenity, 354 participants were included, excluding 8 who responded “I do not meet this circumstance or have never experienced this circumstance” for any item and 7 who responded “do not want to answer/do not know” about their highest education level. The five items were summed (α = .90; range: 5–35) and used as response variables. The mean of gratitude for serenity for writers was 25.24 (SD = 5.89), and for non-writers it was 22.58 (SD = 6.95). The Rhat values for all parameters were 1.0, indicating convergence across the four chains. The results are summarized in Table 1. The posterior distribution of each parameter is shown in the Figure S1.

| Item parameter | Estimate | Est. error | 95% CI [ ] | Rhat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 12.16 | 3.07 | [6.15 18.20] | 1.00 |

| Writers vs. non-writers | 1.89 | 0.66 | [0.59 3.20] | 1.00 |

| Art interest | 2.35 | 0.35 | [1.66 3.03] | 1.00 |

| Age | 0.06 | 0.03 | [0.00 0.12] | 1.00 |

| Years of education | 0.06 | 0.17 | [−0.28 0.38] | 1.00 |

- Note. Estimate = the mean of the posterior distribution for every parameter; Est. error = the standard deviation of the posterior distribution for each parameter; 95% CI [ ] = two-sided 95% credible intervals (l–95% CI and u–95% CI) based on quantiles.

All parameters were Rhat <1.01. Estimated parameters for haiku writers were 1.89 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.59, 3.20), interest in art in general was 2.35 (95% CI: 1.66, 3.03), age was 0.06 (95% CI: 0.00, 0.12), and years of education was 0.06 (95% CI: −0.28, 0.38). These results indicate that haiku writers have higher gratitude for serenity than non-writers, even after excluding the effects of general interest in art, age, and years of education.

The following analyses were conducted on 362 participants. The same GLMM was used to estimate parameters for the sum of the general gratitude trait (α = .86; range 5–35). The mean of the general gratitude trait for writers and non-writers were 24.60 (SD = 4.99) and 24.49 (SD = 5.22), respectively. The effects of general interest in art (1.61; 95% CI: 1.07, 2.16) and age (0.07; 95% CI: 0.02, 0.12) on the general gratitude trait were also found. However, the haiku writer variable had no effect (−0.22; 95% CI: −1.24, 0.80; Table S1). The education variable also had no effect (0.11; 95% CI: −0.16, 0.37). In other words, haiku writers and non-writers had no effect on the tendency for general gratitude but only on gratitude for serenity.

AWE AMONG HAIKU WRITERS VS. NON-WRITERS

The six items for awe were combined (α = .85; range 6–42), and the parameters were estimated using the same GLMM. The results showed that the estimated parameters for haiku writers were 2.65 (95% CI: 1.61, 3.68), general interest in art was 2.60 (95% CI: 2.06, 3.13), age was 0.01 (95% CI: −0.04, 0.05; Table S2), and years of education was 0.24 (95% CI: −0.02, 0.50). These results indicate that the haiku writer variable affected awe even after excluding the effects of general interest in art, age, and years of education.

ADDITIONAL FACTORS RELATED TO SELF-TRANSCENDENT EMOTIONS AMONG HAIKU WRITERS VS. NON-WRITERS

Other individual variables affected by the haiku writer variable were spirituality (0.92; 95% CI: 0.45, 1.40; Table S3), tendency for nostalgia (2.02; 95% CI: 0.68, 3.38; Table S4), and life satisfaction (2.26; 95% CI: 0.90, 3.62; Table S5). When these variables were used as response variables, they were influenced by whether the participants were haiku writers. No influence on mindfulness or religious factors of value orientation was found (Tables S6, S7).

DISCUSSION

This study examined the effects of being a haiku writer or not on the tendency to experience self-transcendent emotions. The findings suggest that gratitude for serenity is higher among haiku writers than non-writers, even when controlling for the effects of general interest in art and years of education. Haiku may have unique influencing processes because of the need to include words related to nature (Rillero, 1999) or daily life (Shirane, 2023). Additionally, scores on the Gratitude Trait Scale, which measures individuals' tendencies to experience gratitude, showed no difference regardless of whether the participants were haiku writers. Therefore, the influence of haiku writing was only evident for gratitude for serenity. While gratitude is generally assumed to be related to events such as receiving gifts, the influence of haiku writing does not mean that it increases sensitivity to such events. Rather, even in the absence of special events, a change in perspective toward everyday life occurs through haiku creation, and people come to appreciate ordinary everyday things through writing haiku. Art and creativity are known to change one's perspective of everyday life (e.g., Glăveanu, 2017), and such a change in perspective was related to feelings of gratitude for serenity.

Our results also indicate that daily haiku writing may increase the likelihood of experiencing awe. Further, haiku writing influences spirituality, tendency for nostalgia, and life satisfaction. Therefore, haiku writing, including the use of seasonal words, may help people focus on larger entities, such as nature, and experience self-transcendent emotions. The fact that well-being has been shown to increase when people feel self-transcendent emotions (Pizarro et al., 2021) suggests that haiku writing may increase life satisfaction by facilitating self-transcendent emotions.

LIMITATIONS

Although this study showed that haiku writers experienced gratitude for serenity and awe, there are some limitations that must be noted. First, because the results are based on survey data, we cannot conclude that haiku writing alone increases the tendency of self-transcendent emotions. For example, people who write haiku may have an interest in nature or a tendency to reflect on their feelings, which may make them more likely to experience self-transcendent emotions, regardless of their haiku writing. Second, related to the first, haiku writers may have originally shown higher levels of openness and creativity-related traits, which may have been confounded. This study measured participants' interest in art in general and controlled for its impact on the analysis. However, what constitutes art may have differed between participants. In addition to engaging in art, people who record their feelings and emotions in a diary or blog, for example, may have a different perspective on their daily lives, as may haiku writers. Therefore, factors related to participants' personalities and behaviors, which this survey did not measure, should be explored in future studies.

Third, the frequency of haiku writing among participants in this study was slightly skewed, with most participants writing 1–3 haikus per month. It would be interesting to examine whether the frequency of haiku writing among the participants changes, including the way they experience self-transcendent emotions. Fourth, an attention check item was included only in the survey completed by non-writers, possibly introducing bias to the collected data. In the future, it would be desirable to include an attention check item in the surveys of both Haiku and non-writers.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

This study's novel finding, the positive relationship between creative haiku writing and self-transcendent emotion, contributes not only to the science of creativity but also to education, as haiku/poetry forms part of the curriculum. In addition, as haiku is easy for anyone to start creating without tools (the 5-7-5 form is even easier than regular poetry), the general population may be able to maintain or improve their mental health in relation to self-transcendent emotions through haiku.

We suggest three future research directions. First, as this study found differences in self-transcendent emotions owing to haiku writing, the causal relationships between these variables should be examined. Haiku creation could increase self-transcendent emotions, or increased self-transcendent emotions could lead people to engage in haiku creation. For example, we can examine the causal effects of haiku creation on self-transcendent emotions by asking people to create haiku and answer a questionnaire multiple times over several months using an empirical sampling method. Second, we should explore how haiku writing affects beginners compared to experienced haiku poets. Third, the mechanism by which haiku writing affects psychological variables must be clarified, including penchants and motives. A unique characteristic of haiku is the use of seasonal words. It is possible that the same effect can be obtained by writing about natural experiences in a diary. Additionally, haiku is the world's shortest poetic form. Therefore, examining other expressions using a limited number of words is necessary. Repeating this activity may improve a person's semantic knowledge of language, vocabulary, and emotional granularity, which might make experiencing/ expressing self-transcendent emotions easier. Such effects, unique to haiku, require further clarification.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors have no funding to disclose.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kanazawa Institute of Technology, Japan. All methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations.

CONSENT FOR PARTICIPATION

We obtained informed consent from the study participants by asking them to press the “I agree” button on a screen containing a survey summary.

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE MATERIAL FROM OTHER SOURCES

Not applicable.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data are available online (https://osf.io/u4fdp/).

REFERENCES

- 1 For example, Kyoshi Takahama, one of Japan's most famous haiku poets, wrote “flowing away, / how fast! / Japanese radish leaves.” This haiku directly describes the speed at which radish leaves flow down a river, but can also be interpreted as reflecting the Buddhist view of life and death that the flow of time does not reverse itself but continues, repeating life and death.

- 2 Haiku gatherings (kukai) in Japan are usually held once a month. Since many people create for these haiku gatherings, we considered haiku writers to have written a haiku in the past month.

- 3 In this study, we added the DQS items only to the non-writers survey. Therefore, we excluded 13 non-writers who answered this item incorrectly. Thus, there were 15 more Haiku writers than non-writers in the data.