Radiography students' knowledge, attitude and practice relating to infection prevention and control in the use of contrast media injectors in computed tomography

Abstract

Introduction

Radiography students complete professional placements in various clinical settings and must adhere to distinct infection prevention and control (IPC) protocols. The aim of this study was to explore radiography students' training, knowledge, attitudes, and practice (KAP) relating to IPC in the use of contrast media injectors in computed tomography (CT).

Methods

An online survey study was undertaken with radiography students enrolled at two Australian universities. Survey questions related to contrast media training and KAP regarding IPC in CT. Data was summarised using descriptive statistics, with comparisons between experience in public and private practice. One free-text response question focused on non-adherence to IPC best practice, analysed using content analysis.

Results

In total, 40 students completed the survey (9% response rate). Reports of IPC and contrast media equipment training was high, with disposition for further training. Regarding IPC knowledge, 65% of students responded correctly to all ‘knowledge’ items (individual scores range: 60–100%). Low consensus was observed regarding whether gloves replace the need for hand hygiene and if CT contrast tubing poses risk to healthcare workers (85% each). Mean scores ranged from 41% to 100% regarding identification of sterile syringe and tubing components. Responses to the open-ended question were categorised into four themes: ‘High non-adherence risk working conditions’, ‘attitudes and practice’, ‘knowledge’, and ‘prioritise good IPC practice’.

Conclusions

Radiography students demonstrate varied comprehension of IPC regarding contrast media equipment, and results suggest need for collaborative efforts between academic institutions and clinical training sites to integrate IPC protocols into curricula and on-site training.

Introduction

Education about infection prevention and control (IPC) is important at every stage of health profession students' training. Previous studies have reported on nurses and other health professions' delivery of IPC training, acknowledging that the formative stages of a health professional's development are key for acquiring knowledge and skills in IPC.1, 2 A review of the nursing literature concluded that the use of new technologies and multiple approaches were necessary to improve levels of IPC knowledge and practice in nursing students.3

Evidence of IPC training for qualified radiographers is available in the literature, with increased research and reporting following the recent COVID-19 pandemic.4-7 For radiography students, when and how IPC knowledge is delivered is not extensively reported in the literature. A study on health profession students, including radiography students at one institution in Ghana,8 found that the main source of information about the prevention of nosocomial infections occurred via formal training during coursework. A more recent study from Sri Lanka found that most radiography students had never participated in an IPC program, and that students' knowledge positively correlated with increased clinical exposure.9 In our experience at two Australian universities, attainment of IPC competency is managed locally by individual educational institutions, and IPC education is delivered within coursework units by academics, and by clinical radiographers when students are completing clinical placements. During clinical placements, radiography students are commonly rostered across multiple medical imaging (MI) clinical areas, such as Computed Tomography (CT), general X-ray, mobile X-ray, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, and surgical theatre, where each work environment demands unique IPC requirements. IPC is not explicitly mentioned in the accreditation standards for approved medical radiation practice programs in Australia.10

Computed Tomography is a specialised area of the MI department, which often involves invasive contrast media procedures, using dedicated equipment such as contrast injectors. Contrast injectors can be generally categorised as single use or multi-use.4 Single-use contrast injectors are designed to be used for a single patient, with all components of the injector intended to only be used once and then disposed. Multi-use contrast injectors have reusable components that allow large bottles of contrast to be used across multiple patients. Only the external tubing, which comes into direct contact with the patient, are typically replaced between patients and considered single-use. The process of administering intravenous (IV) medicines to a patient is sophisticated, and appropriate training should be conducted by licensed professional staff who can ensure the safety of patients and healthcare workers.10, 11 Professional guidelines indicate that only appropriately trained and qualified staff should perform IV cannulations and contrast media injections, indicating that radiography students should not perform these procedures during clinical placements.10-12 Although cannulation is known to be outside of students' clinical experience and scope of practice, anecdotally, during their clinical placements, students participate and support qualified radiographers in various ways. An example includes setting up the contrast injectors. Knowledge of IPC in relation to CT IV contrast injectors enable students to positively contribute to patient care during clinical placements, regardless of the level of participation in the procedure within the healthcare team. This supports the view that contamination risk is minimised when all members of healthcare teams collaborate and strictly follow IPC procedures.13

Previous research has examined radiographers' knowledge, attitudes and practice (KAP) regarding IPC. A recent study reported that Australian radiographers have a good level of knowledge regarding IPC whilst working in the CT environment,14 and whilst education is provided, there are some inconsistencies in training and practice, and high-risk scenarios may influence radiographers to deviate from best practice.4, 15 This is supported by a review focusing on radiographers' preparedness during COVID-19, which concluded that there were inefficiencies associated with IPC, training, and workflow.7 In 2024, an Australian study examined radiographers' roles, responsibilities and practices in CT and found that only 50% of radiographers surveyed reported to have received IPC training within the previous 12 months.4 There are reports that poor handling of contrast media equipment and incorrect IPC techniques can lead to nosocomial infections.6, 17 For example, the transmission of Hepatitis C virus was described in studies relating to contrast enhanced CT procedures,16-18 which likely occurred due to human error.

There is an assumption that students' likelihood of breaching IPC standards is higher compared to qualified staff, due to a lack of training and experience with contrast administration procedures and equipment. To the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of evidence regarding the extent of radiography students' KAP relating to IPC and contrast injectors in the CT environment, as well as students' perception of training received in this area. Given the paucity of literature, and potential need for educational interventions, the aim of this study was to explore radiography students' training and KAP relating to IPC in the use of contrast media injectors in the CT setting.

Methods

This was a descriptive study using an online survey involving quantitative and qualitative data. Students enrolled in any of the existing radiography degrees at two Australian universities were invited to participate in the study via general announcements in each corresponding university's learning management systems. The invitation included a participant information statement, with details of the study, as well as a link to the online survey. The population size was ~450 students enrolled across both institutions. The expected sample size at the onset of this study was expected to be small, considering that students' clinical placement experience in CT may be limited to later stages of clinical placement progression. However, feedback from small sample size was considered effective for this study, considering the lack of literature in this area. Eligibility criteria included undergraduate students enrolled in the 3rd or 4th year of study and graduate entry master's students enrolled in the 1st or 2nd year of study, who had clinical placement experience working in the CT environment (at least one placement, regardless of duration).

Consent of study participation was indicated via survey submission. The online survey was hosted on Qualtrics software. Surveys were anonymous and study participants could enter a draw to win one of 20 $10 supermarket vouchers at the completion of the survey. Data collected from students to register their interest in entering the draw was via a separate survey to ensure data collected in main survey remained anonymous. Data collection occurred over a 12-month period, closing in March 2024. Invitations to participate in the study were sent periodically to align with clinical placement timelines for each cohort. Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committees from The University of Sydney (Project number: 2023/015) and The University of Canberra (Project approval ID: 13418).

The survey was developed by the researchers, integrating previous literature and existing guidelines in IPC.19, 20 The first part of the survey consisted of demographic questions (gender, university, enrolment program, enrolment year, duration of clinical placements with CT experience, most recent clinical placement type with CT). Subsequent sections were divided into knowledge, attitudes, and practice (all survey items are listed in Figs. 1-4 and in-text results), with a combination of response options including ‘true’ and ‘false’, and five-point Likert scales, ranging from ‘always’ to ‘never’ or ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. In the section on practice, students were asked to provide a free text response to the statement: “If I was to not follow the procedure I was taught about CT contrast injectors, it was most likely when…”. The aim of this question was to capture students' perspective and/or experience with scenarios where adherence to IPC was challenged. The final survey section included four images, labelled A, B, C, D, showing several syringe and tubing components. For each image, students were asked to indicate if they could identify components that should be sterile (‘yes’ or ‘no’ response) and then, to specify which of the images' labelled components should remain sterile (select all that apply).

Data analysis

Demographic data was analysed descriptively using frequency of percentage responses. Student demographic data was collected to describe the participant sample only, as it was not deemed appropriate to compare differences between collected characteristics and survey responses. In addition, the resulting sample size would be of limited validity. Likert scale responses were collated per survey question, and percentages calculated. For the knowledge section, student scores were compared using Mann–Whitney U test for differences between most recent placement sites (Private and public). For training and workplace questions, responses were compared between most recent placement site (Private and public) using Chi-Square calculation. SPSS version 28 was used for statistical analysis and the P-value was set to 0.05.

The open-ended responses to the question “If I was to not follow the procedure I was taught about CT contrast injectors, it was most likely when…” was analysed using content analysis.21 A previous study used a similar question with qualified radiographers as study participants,15 and the themes from the previous study (‘High non-adherence risk working conditions’, ‘compliance with good practice’, ‘attitudes and practice’, ‘ineffective communication’) were used as an initial framework/matrix for the current study's student responses. The aim of the content analysis was to identify students' perceptions of scenarios in which IPC would not be adhered to. Each student response was coded and categorised to identify common elements among responses. The codes were then merged based on similarity and categorised into previously described framework. Two independent authors conducted this process and reached consensus of final four themes via discussion. One additional theme was added to the resulting categories (‘knowledge’) and one existing framework theme (‘ineffective communication’) was removed, as no coded items could be categorised into this theme. In each theme, each similar code occurrence was added up per category, and converted to percentages of the total number of codes occurring in that theme. The themes were ranked according to the highest percentage of responses.

Results

A total of 40 students returned complete surveys during the study period (response rate = 9%). Table 1 shows demographic characteristics of study participants. Study participants were predominantly female (85%, n = 34/40), enrolled in an undergraduate degree (83%, n = 33/40), and had their most recent placement in private practice (52%, n = 21/40). There was almost equal participation from the two targeted institutions, 55% (n = 22/40) from The University of Sydney and 45% (n = 18/40) from The University of Canberra. Participants' placement experience with CT ranged from 2 to 5 weeks in duration, with an average of 3.4 ± 1.8 weeks (median = 3 weeks).

| Subcategories | Total n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 34 (85) | |

| Male | 6 (15) | ||

| Enrolment | Undergraduate | Year 3 | 12 (30) |

| Year 4 | 21 (53) | ||

| Postgraduate | Year 1 | 2 (5) | |

| Year 2 | 5 (12) | ||

| Most recent placement location | Public | 19 (48) | |

| Private | 21 (52) | ||

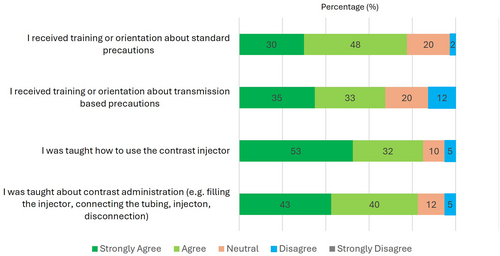

Training

A high proportion of students agreed or strongly agreed that they had received training about standard precautions, transmission-based precautions, use of contrast injectors, and contrast administration, as detailed in Figure 1. As shown in Figure 2, most students agreed or strongly agreed that their awareness of IPC in CT was adequate (70%, n = 28/40) and that training in the use of contrast injectors was adequate (65%, n = 26/40), yet a high proportion of students would also prefer a formal course in contrast injectors (80% agreed or strongly agreed, n = 32/40). Only 33% of students (n = 13/40) agreed or strongly agreed that their understanding of contrast injectors is adequate and do not require additional education.

Knowledge about contrast injector components

Students were presented with an image of a multi-use injector and asked to indicate its purpose from a list of four options. Only 78% (n = 31/40) recognised the image as a multi-use injector, whereas 98% (n = 39/40) recognised that the injector is not used for radioisotopes, only 63% (n = 25/40) agreed that it is used for IV iodinated contrast and even less (n = 15/40, 38%) selected that it is used for IV saline. After presenting the students with an image of a contrast injector, one positively and one negatively worded question were included, asking about confidence using the injector and another asking if they were confused using the injector. When asked if they felt confident using the injector in the supplied image, 65% (n = 26/40) agreed or strongly agreed, whereas 28% (n = 11/40) remained neutral. Students were also asked if they get confused when using the injector in the supplied image and 48% (n = 19/40) disagreed or strongly disagreed but 40% (n = 16/40) remained neutral. The majority of the participants that had negative responses to the two questions on injector use opted for ‘neutral’ in the opposing question.

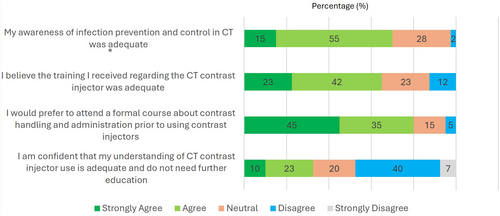

Individual scores for the knowledge questions posed in the survey ranged from 60 to 100%, with 65% (n = 26/40) of students responding correctly to all items. Figure 3 presents percentage of students' knowledge scores, which had 85–100% consensus across the different factors and an average score of 95% ± 10%. Of the ten factors, a 100% score was achieved regarding transmission of infections through hand contact with CT department equipment. While still high at 85%, lower consensus was achieved regarding whether gloves replace the need for hand hygiene and if CT contrast tubing poses no risk to healthcare workers. Regarding students' self-rated confidence to distinguish parts of the contrast injector tubing and syringe that should remain sterile, 68% (n = 27/40) agreed that they were confident and 25% (n = 10/40) indicated ‘neutral’ as a response. Only three students disagreed that they felt confident (8%, n = 3/40).

Students were then presented with four images of contrast injector tubing and syringes, as shown in Table 2. For each image, students were asked if they knew which components were sterile. Only three students (8%) said ‘no’ to some or all the images. Of these three students, only one had indicated that they were not confident in distinguishing parts of the contrast injector and tubing that should remain sterile in a previous question. Students' overall mean score when indicating which labelled parts should remain sterile across the four images was 77 ± 21%, ranging from 41% to 100%, and detailed for each component in Table 2. The most correctly identified component was the contrast tube tip (Table 2, Image D, label 3), with 98% correct responses. The least correctly identified component was neck of syringe (Table 2, Image A, Label 2), with only 35% correct responses.

| Image description | Component label | Correct response rate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image A. Contrast injector syringe |

|

1 2 3 4 |

68% 35% 88% 95% |

| Image B. Contrast injector syringe end with contrast tubing end |

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

85% 73% 93% 93% 80% |

| Image C. Contrast injector syringe with spike for contrast loading |

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

85% 75% 43% 80% 70% |

| Image D. Contrast tubing end |

|

1 2 3 |

90% 65% 98% |

Observed practice and self-reported practice

Students were asked if they observed staff not adhering to standard precautions when handling the contrast injectors at their clinical placement, and 5% (n = 2/40) and 18% (n = 7/40) selected ‘always’ or ‘frequently’ respectively. When students were asked if staff used standard precautions for connecting or disconnecting IV contrast lines from the patient, there was a higher level of adherence by staff as reported by students. Students responded ‘always’ (25%, 10/40) or ‘frequently’ (43%, 17/40), and none of the students selected ‘never’ as an option.

Students' involvement in CT varied. Many students were involved in CT and contrast media procedures, and only four students rarely (5%, n = 2/40) or never (5%, n = 2/40) set up the IV contrast injector. This increased to 35% (n = 14/40) for connecting or disconnecting the IV contrast tubing to and from the patient and for injecting the IV contrast into the patient as part of the CT examination. The majority of students (83%, n = 33/40) agreed that they preferred to use standard precautions before handling the IV contrast lines, whereas the remaining students selected neutral.

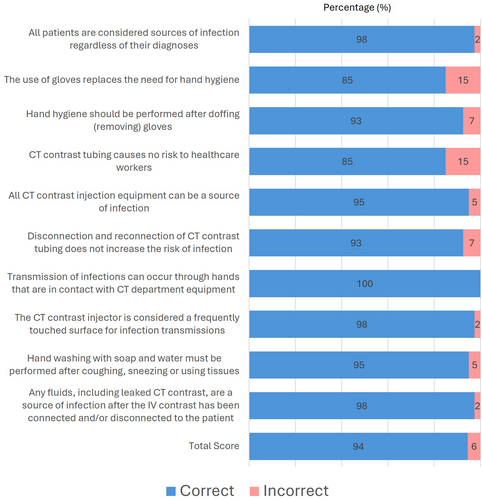

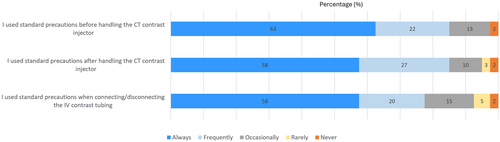

Students were then asked if they apply standard precautions and Figure 4 presents their responses. Only one student (2%) selected ‘never’ for all three questions, but had also answered ‘never’ to performing roles in CT relating to the contrast injector. Only 10% (n = 4/40) disagreed that they had enough time to apply standard precautions before handling the IV contrast lines, but 25% (n = 10/40) responded ‘neutral’. Students were also asked if they would accept an IV contrast CT scan at the level of sterility or cleanliness that they practice. The majority of students agreed (n = 15/40, 38%) or strongly agreed (33%, n = 13/40). Only 13% (n = 5/40) disagreed, whereas the remaining 18% (n = 7/40) remained neutral.

There was no statistical difference regarding training and perception of training, scores for knowledge questions, identification of contrast injector components, and students' responses to application of standard precautions between students who completed placement in private or public placements.

Situations when correct IPC procedures would not be followed

From 40 survey respondents, 37 participants responded to the open-ended question (3 respondents were excluded as they did not provide a response). The open-ended question was worded to specifically identify situations where IPC adherence may be challenged. The 37 responses generated 47 codes, as some student comments contained more than one code, there were more codes than study participants. Table 3 shows the categorisation of codes into four themes: 1. High non-adherence risk working conditions (55%, 26/47 codes), 2. Attitudes and practice (23%, 11/47 codes), 3. Knowledge (13%, 6/47 codes), and 4. Compliance with good practice (9%, 4/47 codes). Responses were most frequently categorised into ‘time pressures and staffing issues’ category (38%, 18/47 codes), in the theme ‘High non-adherence risk working conditions’.

| Ranking | Theme | Category | Sample student quote | Code count | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | High non-adherence risk working conditions | Time pressures and staffing issues | “The department was busy, and we had multiple patients coming after another that needed to be scanned quickly” [S4] | 18 | 38 |

| Complication during procedures | “The patient had an adverse reaction” [S7] | 3 | 6 | ||

| Trauma and emergency settings | “There were trauma patients and time was limited” [S26] | 3 | 6 | ||

| Unwell patients (non-emergency) | “With patients who are not comfortable or a little bit claustrophobic” [S5] | 2 | 4 | ||

| 2 | Attitudes and practice | Influence from supervising radiographer | “A staff member told me not to do so.” [S10] | 6 | 13 |

| Not students' role | “There were medical imaging nurses who did majority of the connecting/disconnecting of the IV contrast” [S27] | 4 | 9 | ||

| Variation of practice from previous placement | “[explanation of procedure…] this was different to other placements where the whole kit was disposed for each patient” [S22] | 1 | 2 | ||

| 3 | Knowledge | Lack of knowledge/practice | “Early placements when we did not get taught about CT” [S11] | 6 | 13 |

| 4 | Compliance with good practice | Prioritise good IPC practice | “This did not occur. I was very meticulous with hand hygiene and procedure” [S33] | 4 | 9 |

| Total | 47 | 100 |

Discussion

This study aimed to explore radiography students' training, KAP relating to the use of IV contrast media injectors in the CT setting. Most students reported satisfaction with training they received on clinical placement, suggesting that clinical educators meet student radiographers' education needs around this topic, presumably as part of their orientation to the work environment. It is likely that further integration of IPC within coursework curricula is necessary to support clinical-based training, as there was a high preference by study participants for further formal training in contrast handling and administration. Hence radiography students' IPC and CT environments' teaching and training requirements should be further assessed, applying findings from previous studies in nursing and medical students.1-3 Recommendations to increase knowledge and improve attitude and practice towards IPC in the nursing context may be analogous to the needs of student radiographers, and include periodic training, relevant practical courses, combination of theory and practice and training at the beginning of hospital employment.22 However, for maximum benefit, educators should also focus on the unique requirements of the CT environment and IV contrast media, to enable students' safe participation within the healthcare team, whilst considering the limited scope of students' practice in this setting.11, 12 A standard approach across the radiography profession may be beneficial, because although infection control departments govern IPC in medical environments, lack of specific IPC protocols for unique clinical settings such as CT, and low IPC compliance are significant barriers to combating infections.23 Further, students could be taught differently in various clinical settings and by different radiographers about handling contrast injectors, including with a non-IPC compliant approach, which undermines the core principles of IPC. MI departments will normally be working within the IPC regulations and protocols that govern their local practice.

Knowledge of IPC is a key requirement for safe practice in health profession student programs. As shown by responses to an open-ended question in this study, students reported that lack of knowledge contributed to non-adherence to best IPC practice (13% of responses in this question). In addition, students were also alert to other healthcare professionals not following correct procedures, suggesting awareness of poor practice and lack of compliance with best IPC practice. Overall, knowledge scores were above 60% for students who participated in this study, with a 65% of students responding correctly to all knowledge items (Fig. 2). These results demonstrate diverse knowledge levels among students at the later stages of their university training. The lowest percentage of correct responses (85%) in the knowledge section was observed for two questions, one asking whether gloves replace the need for hand hygiene and the other if CT contrast tubing poses no risk to healthcare workers. Similar questions were posed to qualified radiographers in a previous study,14 which had higher percentage of correct responses (above 93%), inferring that increased knowledge aligns with clinical practice and experience upon graduation. We did not intend to identify differences in students' knowledge scores across demographic factors and when comparing data with existing literature, it can be challenging to compare IPC knowledge and practice between student radiographers in different countries, due to lack of similar studies and variation of IPC practices across geographical regions.23 However, our results align with findings from a previous study, which confirmed that IPC knowledge increased with clinical exposure and years of enrolment.9

The core principle to prevent nosocomial transmissions from occurring in injection practice is to keep the injection devices and the internal content sterile.24 Knowledge of sterile components of syringes and tubing via visual cues demonstrated diversity in students' knowledge regarding sterile components despite scoring above 60% on knowledge statements on standard precautions. A high proportion of components labelled in the four images were correctly identified by students. However, incorrect identification of sterile components in the images were also recorded, suggesting that students' perception of their knowledge and actual practical knowledge have not aligned in this study, with further education bridging this gap potentially providing opportunity for ensuring expertise. This is an important result, as awareness and adequate knowledge about sterile component are essential for radiography students to contribute to safe patient care during their training, and to avoid infection risks once they have greater responsibility as qualified radiographers, as human errors have been reported to result in detrimental patient outcomes.17, 18

Responses to an open-ended survey question described scenarios that radiography students considered to impact on best IPC practice, to better understand challenges in IPC adherence faced by students in the clinical setting. The highest ranked theme related to high non-adherence risk working conditions related to situations associated with time pressures and staffing issues, complication during procedures, and trauma and emergency settings. These were comparable to scenarios described by qualified radiographers in a recent study,15 suggesting that these situations are not isolated to students' experiences but rather the health environment. In contrast to the responses provided by qualified radiographers in a previous study,15 students in the current study included unwell patients (non-emergency) in their responses, providing an insight into students' developing skills to cope with a range of patient presentations, which qualified radiographers may have already mastered. The role of students as learners within the clinical setting was also emphasised in the open-ended responses, with impact on best practice reported from lack of knowledge, as well as supervising radiographers' directions and variation of practice across students' different placement sites. Some students' responses did not answer the question directly and inferred that a commitment is made to ensure high standard of IPC practice.

Implications for practice

It is evident that there is a critical need to enhance IPC training among radiography students, particularly in relation to the use of contrast media injectors in CT environments, posing significant implications for practice. Firstly, academic institutions and clinical training sites must collaboratively work towards integrating and reinforcing IPC protocols within the curriculum and on-site training. This could involve the development of formal courses or modules focused specifically on CT contrast injector usage, handling, and administration, underpinned by robust IPC principles. Given the high preference among students for formalised training, there is an undeniable gap in current educational offerings that needs to be addressed. Secondly, the variability in students' knowledge and practice highlights the importance of standardised IPC training across different clinical settings. Unified IPC guidelines and training programs for CT environments could ensure consistent practices are taught and adhered to, regardless of the clinical setting. This is crucial not only for improving students' knowledge and competence but also for minimising the risk of nosocomial infections, thereby enhancing patient safety. The engagement in hands-on, practical learning experiences, alongside theoretical instruction, should be encouraged to bridge the gap between students' perception of their knowledge and their practical skills, particularly concerning the identification of sterile components and the correct use of contrast injectors.

Limitations

The majority of study participants were enrolled in a final year undergraduate program; hence responses may be aligned with students with greater academic and clinical experience. The study sample was small, which was an anticipated limitation considering that many students would not have attended placements with opportunity to work in CT environment, and that not all students would have been permitted to use contrast injectors. The data collection tool used in this study was a not a validated survey and the data collection used in this study was via a self-reported survey, however, as an anonymous survey, it provides confidence that students were able to answer questions truthfully. Despite these limitations, results from this study offers opportunities and challenges to consider for academic and clinical educators and sets foundation for future exploration of students' attitudes through focus group and evaluation of educational interventions.

Conclusions

Appropriate knowledge of IPC in relation to CT contrast injectors is a critical prerequisite for positive attitudes and practice in IPC, which will support safe health care delivery at any stage of an individual's training and profession. Student radiographers demonstrated diverse understanding of IPC relating to contrast media equipment and majority of study participants were able to identify components that should remain sterile. Due to diverse levels of knowledge, which may promote incorrect attitudes and practice, results from this study suggest that academic and clinical educators need to collaborate to target IPC education and clinical practice opportunities. Increasing emphasis on IPC in the curriculum for unique IPC requirement the clinical setting, may improve students' KAP, supporting a positive patient safety culture.

Acknowledgements

Kwan Chak Chow contributed to early stage of survey design.

Conflict of Interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research was funded by Imaxeon PTY LTD (Australia), Grant ID: 214490. The authors are independent from the funding body, and the views expressed in this publication are those of the authors.

Authors Contributions

Dania Abu Awwad (DA), Suzanne Hill (SH), Minh Chau (MC), Sarah Lewis (SL), Yobelli Jimenez (YJ) contributed to conception and design of study. DA, SH, MC, SL, YJ developed the survey instrument. DA, MC, YJ collected study data. DA and YJ performed data analysis. YJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript, DA, SH, CH, SL revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committees from the University of Sydney (Project number: 2023/015) and University of Canberra (Project approval ID: 13418).

Consent to Participate

The study was approved by an appropriate ethics committee and all persons gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.