A systematic literature review of reciprocity in engineering service-learning/community engagement

Abstract

Background

Scholars agree that reciprocity is a cornerstone of service-learning and community engagement (SLCE); however, engagement with this concept varies widely in practice and across disciplines. To enhance the potential of SLCE to fulfill its promise for societal impact, engineering education must understand how reciprocity is achieved, recognize barriers that inhibit its progress, and identify strategies for how it can be strengthened.

Purpose

We performed this review to understand the ways reciprocity is articulated in the engineering SLCE literature. Drawing from these articulations, we examined the extent of engagement with reciprocity toward providing insights into the design and assessment of SLCE efforts for reciprocity.

Scope/Method

We performed a systematic literature review on engineering SLCE at institutes of higher education. Following an established approach to identify and synthesize articles, we developed deductive codes by distilling three well-articulated orientations of reciprocity. We then analyzed the operationalization of reciprocity in the literature.

Results

The literature demonstrated varying degrees of reciprocity. Minimally reciprocal efforts centered university stakeholders. In contrast, highly reciprocal partnerships explicitly addressed the nature of engagement with communities. Findings provide insights into the breadth of practice within reciprocity present in engineering SLCE. Further, analysis suggests that our codes and levels of reciprocity can function as a framework that supports the design and evaluation of reciprocity in SLCE efforts.

Conclusions

Our review suggests that to enact more equitable SLCE, researchers and practitioners must intentionally conceptualize reciprocity, translate it into practice, and make visible the ways in which reciprocity is enacted within their SLCE efforts.

1 INTRODUCTION

Reciprocity, an essential cornerstone for practicing ethical and high-quality service-learning/community engagement (SLCE), is the mutuality in a partnership between an educational institution and a community (Bloomgarden, 2013). SLCE efforts achieve reciprocity when all stakeholders agree on and engage with the problems identified, approaches used, and achieved impacts (Drahota et al., 2016; Hammersley, 2012; Henry & Breyfogle, 2006). SLCE grounded in reciprocity provides opportunities for both the educational institution (e.g., university or other academic unit) and the community (e.g., community centers, neighborhoods, non-profits and their supported constituents) to contribute to, benefit from, and evolve within the partnership; it also ensures that SLCE efforts are built on long-term, trusted relationships (Clayton et al., 2010; Cooper & Orrell, 2016; Mitchell, 2013; Nieusma & Riley, 2010). Reciprocity's emphasis on mutuality across SLCE contexts and practices makes it a useful criterion for understanding, evaluating, and advancing equity across SLCE partnerships.

Although reciprocal SLCE partnerships work to ensure mutual benefits for stakeholders, partnerships that omit or pay lip service to the concept of reciprocity fail to achieve their core purpose, and may even harm vulnerable stakeholders, including communities and students (Marullo & Edwards, 2000; Pompa, 2002). Examples of these harms have been documented, including SLCE efforts that reinforce stereotypes and problematic social hierarchies, prioritize university outcomes and needs over those of the community, and produce outcomes misaligned with community needs (Chesler & Scalera, 2000; Conner & Erickson, 2017). When repeated over time, these imbalanced and inequitable partnerships compromise the trust between community members and partner institutions, and genuine community impact cannot be achieved.

In the last 20 years, the articulations of reciprocity in the SLCE literature have highlighted its complexity and elusiveness. Scholars have focused on reciprocity to describe three primary aspects of SLCE efforts where it can manifest: nature of relationships among stakeholders; ways through which needs or problems are addressed; and outcomes that are generated. For example, Henry and Breyfogle (2006) call attention to all three of these aspects in their discussion of the transactions between the “service providers” and “service receivers,” as well as the mutuality between the needs and outcomes of these stakeholders (Henry & Breyfogle, 2006). Kendall (1990, as cited in Henry & Breyfogle, 2006) focuses on relationships and highlights the role of exchange in the relationships, defining reciprocity as the “… giving and receiving between the server and the person or group being served” (p. 27). Janke and Clayton emphasize equity and define the roles of each stakeholder: “[reciprocity is about] recognizing, respecting, and valuing … the knowledge, perspective, and resources that each partner contributes to the collaboration” (2012, as cited in Davis et al., 2017, p. 36). Caruccio (2013) further deepens our understanding of exchange in reciprocal SLCE efforts by emphasizing equitable distribution of benefits, risk, contribution, and recognition of stakeholder efforts: “[A reciprocal SLCE effort is] one characterized by mutual benefit, shared risk, collaboration, and an acknowledgment that all parties are serving and being served” (p. 3). These different definitions show how researchers and practitioners think about reciprocity in the theory and practice of SLCE.

Following Trainor and Bouchard (2013), our initial exploration of the engineering SLCE literature echoes their conclusion that “reciprocity was not identifiable as a singular, stalwart concept” (p. 999); in addition, we observe that outside of engineering, work on reciprocity has sought to examine its role in advancing equity and justice in the theory and practice of SLCE. In the social sciences, D'Arlach et al. (2009) defined reciprocity from the perspective of both students and community participants, while Mannion (2012) used an intergenerational learning perspective. Other disciplines highlight how reciprocity is enacted through behaviors in learning processes: for example, health practitioners build participatory relationships with their patients (Melby et al., 2016), and preservice teachers mutually learn “with” and “from” community youth (Donahue et al., 2003).

These recent studies suggest that, rather than using a single definition, a systematic and multifaceted approach for understanding reciprocity might better support researchers and practitioners in addressing its complex and varied nature in SLCE. In perhaps the most comprehensive review of this complexity to date, Dostilio et al. (2012) looked across disciplines and knowledge traditions to orient reciprocity in SLCE. Their review connected current uses of reciprocity to earlier theoretical work exploring social relations (Gould, 1983), the logic of collective action (Olson, 1965), reciprocal determinism (Bandura, 1977), and several indigenous epistemes (e.g., Harris & Wasilewski, 2004; Kovach, 2009). From this synthesis, Dostilio et al.'s (2012) concept analysis of reciprocity characterizes it across three orientations—exchange or interchange of actions, benefits, and resources; influence, how outcomes of a partnership are influenced by stakeholders' knowledge and actions; and generativity, the extent to which stakeholders collaborate to develop something new that does not otherwise exist. These three orientations represent a robust and nuanced conceptual framework for characterizing reciprocity in a given SLCE effort.

Engineering educators interested in reciprocity will note that engineering SLCE literature rarely prioritizes it. This gap was noted by Oakes et al. (2002), who showed that engineering tends to lag most other disciplines in its acceptance of SLCE pedagogies, as evidenced in the uneven distribution and various forms of SLCE used in engineering education. Owing to this uneven distribution, what is known about reciprocity's effects in other disciplines is only partially integrated in engineering. This highlights the need to better understand reciprocity's presence in engineering SLCE. This exploration is especially vital, because focusing on reciprocity in this context may help explain how educators' and practitioners' implicit beliefs—especially those harmful or problematic beliefs—affect community outcomes (Delaine et al., 2021; Delaine & Thompson, 2021) while also supporting engineering alignment with justice and sustainability (Leydens & Lucena, 2017; Lucena et al., 2010).

To address this gap in our understanding of reciprocity in engineering SLCE, we conducted a systematic literature review of SLCE publications in engineering. Our goal was to explore how the various elements of reciprocity have been conceptualized, incorporated into pedagogical design, interpreted, and enacted in the engineering literature. Therefore, this study aimed to answer two research questions (RQs):

RQ1.In what ways is reciprocity articulated in the literature of engineering SLCE?

RQ2.What do articulations of reciprocity (or lack thereof) suggest about the forms and extent to which reciprocity is manifested in engineering SLCE?

By answering these questions, this systematic review makes two contributions: we characterize articulations of reciprocity across the literature and establish an analytical framework to more effectively enact reciprocity in engineering SLCE. Specifically, we add (i) an emergent analytical framework providing criteria for integrating, evaluating, and disseminating reciprocity in engineering SLCE, and (ii) patterns in reciprocity indicators across eight framework elements and the differing levels to which they appear. This review explores reciprocity's manifestations in engineering to aid practitioners and scholars in investigating, enhancing, and promoting equitable SLCE practice.

2 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Our systematic review is conceptually grounded in Dostilio et al.'s (2012) conception of reciprocity. Scholars have attempted to account for the complex instantiations of reciprocity in SLCE by developing frameworks to understand and characterize it. Although they differ in emphasis—for example, some emphasize the relationships among stakeholders, while others are more concerned with the impacts and outcomes of those relationships—most depend on comparison for understanding reciprocity. For example, Jameson et al. (2010) compare SL relationships by introducing a spectrum with poles of “thick” and “thin” reciprocity. On this spectrum, stakeholders in “thinly” reciprocal relationships interact transactionally and focus on technical outcomes. The authors contrast this relationship with those on the other side of the spectrum, where “thickly” reciprocal SL relationships prioritize not just technical outcomes but achieving mutual outcomes through joint project ownership and co-creation of ideas, knowledge, and power. Because these kinds of relationships tend to produce more mutually beneficial and equitable outcomes, Jameson et al. suggest that these “thickly” reciprocal partnerships are more valuable.

While Jameson et al. assign greater value to SLCE relationships on the “thick” side of the spectrum of reciprocity, Enos and Morton's (2003) partnership typology weaves value-laden assumptions into its organizing logic. Enos and Morton's framework assigns different values to “transactional” versus “transformational” relationships. Transactional relationships, where partners engage in transitory exchanges to accomplish a particular task, are valued less than transformational relationships. In transformational relationships, partners engage in open-ended, ongoing exchanges to collaboratively work and build knowledge. Using this partnership typology, reciprocity in an SLCE effort is assessed by comparing the effort's relationships across their duration, depth, and complexity.

Thompson and Jesiek (2017) build on the Enos and Morton (2003) partner typology to propose a transactional, cooperative, and communal (TCC) model that focuses on partnerships in engineering. In this model, the transitory exchanges characteristic of transactional partnerships are also characterized by the presence of another social dimension, wherein partners perceive or create a “distinct boundary between stakeholders, thereby tending to preserve or enhance a sense of ‘us’ and ‘them’ between the participant groups” (Thompson & Jesiek, 2017, p. 85). Unilateral partnerships, where the perceived distance between participant groups is substantial, can be exploitative; Thompson and Jesiek note that, by definition, transactional-exploitative partnerships are not reciprocal. In contrast to the “us/them” divide established in transaction partnerships, the TCC model describes cooperative relationships, where partners work together as a single team with a “we” mentality. In cooperative relationships, including the needs of both partners is an essential component because the process in which the partners work is as important to consider as what the partners produce (Thompson & Jesiek, 2017). Finally, in communal partnerships, boundaries are “permeable and transcend the participating groups to include the community and/or the society as a whole” (Thompson & Jesiek, 2017, p. 85). Thompson and Jesiek, like Enos and Morton, introduce more categories and granularity for identifying and evaluating elements of reciprocity in SLCE, but Thompson and Jesiek also build in logic comparison for identifying reciprocity.

The schemas we have summarized present valuable insight into the various ways reciprocity has been framed in existing SLCE literature. However, they are constrained in that they are largely dependent on comparison—transactional partnerships are different from (and less “good” than) transformational partnerships; cooperative relationships are different from (and less “good” than) communal partnerships. Evaluating an SLCE effort by comparison to an imagined ideal (“transformational”; “communal”) can inhibit a robust understanding of the extent to which reciprocity is present in an SLCE publication.

A concept analysis (Hupcey & Penrod, 2005) of reciprocity conducted by Dostilio et al. (2012), however, positions reciprocity outside of comparative, value-laden formulation; instead of evaluating the extent to which the reciprocity in a given SLCE effort is “ideal” or “authentic,” their orientations reveal the “diverse conceptualizations contained in the term” (Hammersley, 2012). In seeking to avoid the limitations of comparison or a priori valuations of particular forms of engagement, Dostilio et al. (2012) contribution is notable in both its scope—reviewing SLCE literature from engineering as well as from other disciplinary perspectives—and comprehensiveness. Their review constitutes a comprehensive review of the relevant scholarship and its applications. To our knowledge, no other concept analysis of reciprocity has been conducted that is germane to the practices of SLCE; consequently, Dostilio et al. (2012) remains an authoritative resource upon which we ground the conceptual framework for our systematic review.

Dostilio et al. (2012) use a concept analysis to provide a comprehensive description of the forms of reciprocity connected to the ways of relating, knowing, and being among stakeholders along three orientations: exchange, influence, and generativity (further articulated in Appendix, Table A1). In Appendix, Table A1, we provide descriptions and examples of the three orientations to highlight the ways that differences in how partnerships are enacted correspond to the orientation in which reciprocity is manifested in the same engineering SLCE context. By choosing to describe reciprocity using “orientations,” Dostilio et al. break from existing frameworks, which situated reciprocity in partnerships along a spectrum of valuation. The term “orientation,” itself, suggests a descriptive, nonlinear, nonhierarchical approach to the ways in which reciprocity might be enacted in different contexts. At a minimum, the orientations provide interpretive lenses for clarifying what is conveyed when the term “reciprocity” is invoked in a program description or implementation model.

To identify how reciprocity is articulated in engineering SLCE, we operationalized Dostilio et al. (2012) orientations as a conceptual basis for coding and evaluating literature in our systematic review. Our approach to the systematic review and analytical procedures is detailed in the following section.

3 METHODS

This systematic literature review was conducted following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines and Borrego et al.'s recommendations for reviews in engineering education (2014). The following section provides a description of our review method, including information retrieval, inclusion criteria, selection process, as well as limitations to our approach. The synthesis stage of our systematic literature review process will follow the Methods in a separate Section 4.

3.1 Literature search strategy

To establish our dataset, first we developed search terms based on (i) our research questions within engineering education and (ii) keywords related to SLCE and reciprocity. Our intent in using these as search terms was to capture the breadth of literature connected to reciprocity. We used Boolean operators to incorporate synonyms and link major terms. The complete search string used was as follows: (engineering education) AND (partnership OR collaboration) AND (“service learning” OR “service-learning” OR “community engag*” OR “civic engag*”) AND (university OR college OR “higher education” OR “post-secondary” OR postsecondary).

To identify the most appropriate databases to conduct our search, we consulted a subject librarian in engineering education and selected the following: (i) Educational Resources Information Center (EBSCO), (ii) Academic Search Complete, (iii) Education Full Text (H.W. Wilson), and (iv) Education Research Complete.

After searching each of these databases, an initial review suggested that we were not capturing conference proceedings. Because conference proceedings and other “gray literature” can be a valuable source of information in engineering education systematic reviews (Borrego et al., 2014), we completed an additional ERIC database search using the publisher limiter “ASEE” to yield relevant results from the annual meeting of the American Society for Engineering Education. Because the majority of ASEE proceedings are evidence-based practice papers, by including these papers we enriched and expanded our dataset for analyzing the form and extent to which reciprocity is present in practice.

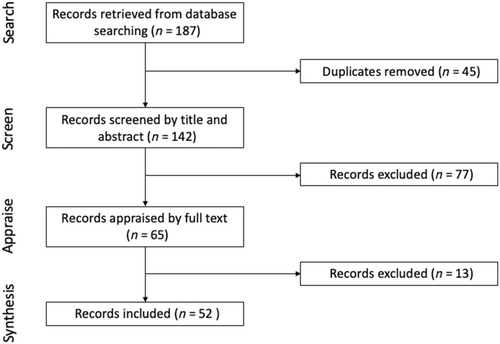

Our initial database search retrieved 187 relevant records. After duplicates were removed, 142 articles remained.

3.2 Inclusion criteria

Our database search criteria included scholarly, peer-reviewed journal articles and ASEE conference proceedings published between 2000 and 2021. We chose our search period (i.e., 2000–2021) to align with the emergence of engineering education as a field (Froyd & Lohmann, 2014). This window of time also corresponds to a phase of increasing interest in engineering SLCE, and includes publications produced both before and after the Engineering Projects in Community Service (EPICS) program was established (EPICS; Coyle et al., 2005). EPICS has been a highly influential engineering service-learning model throughout the last 15 years, and scholarship on its programming has been disseminated widely to a variety of colleges and universities.

To further tighten the scope of our results for our research questions, we required that all articles explicitly include an engineering context rather than a broad inclusion of the STEM fields. Our inclusion criteria also targeted higher education settings, so we excluded articles that focused exclusively on K–12 programs. Because we are interested in reciprocity as it manifests in SLCE, in our review, selection criteria required that an article have one of the following components: service-learning, community-based learning, or a community-engaged, or university–community partnership. In addition, we chose articles where these components follow one or more of the integration models described by Oakes (2004): integration into existing courses; integration with co-curricular components; new SLCE courses; or SLCE programs. Because prior work (e.g., Salam et al., 2019) shows that SLCE frequently includes cross-national experiences as well as domestic partnerships (and that benefits differ across the contexts), we included both domestic and international SLCE. Table 1 summarizes our inclusion criteria.

| Category | Inclusion criterion |

|---|---|

| Time | Published between 2001 and 2021 |

| Context | Addresses engineering concepts |

| SLCE participants from post-secondary and higher education | |

| Service-learning | |

| Community-based Learning | |

| Community-engaged | |

| University–community Partnership | |

| International | |

| Domestic | |

| Integration model | Integration into existing courses |

| Integration with co-curricular components | |

| New or existing SLCE courses | |

| New or existing SLCE programs |

3.3 Selection process

To complete the selection process, articles were randomly assigned to teams of reviewers who then screened each by title and abstract by applying the inclusion criteria. Each abstract was evaluated independently by at least two reviewers. If consensus between the initial two reviewers could not be achieved, a third reviewer evaluated the abstract and applied screening criteria to determine inclusion. A total of 65 papers were retained for evaluation for the next stage of the literature review.

After the initial abstract screening, the full text review of each of the 65 remaining papers was then coded independently by two reviewers. From this process, papers were eliminated because criteria for inclusion were not met: SLCE was absent (n = 11) and engineering concepts were absent (n = 2). Our final stage of the selection process left a total of 52 articles for full study inclusion. Details of the search, screening, and selection process are provided in Figure 1.

3.4 Limitations

There are three main limitations to the methods used. First, we acknowledge that our search terms might not have been broad enough to elicit articles describing the full range and variety of ways that institutions and communities may partner and connect. Various orientations to university–community relationships are reflected in the terminology used in publications. We attempted to capture these diverse approaches through our search terms but, in our focus on SLCE in engineering and higher education, it is possible that we have unintentionally excluded some relevant studies.

Additionally, we narrowed our examination of the literature to engineering-specific efforts. Based on our research questions, a broader consideration of STEM-related SLCE efforts was not included in this review. It is possible that a wider examination of the field of STEM would provide a more comprehensive view of the elements of reciprocity that are currently in practice, but because many of these likely include particular disciplines within STEM (e.g., biology or chemistry), we believe that it would skew our ability to make compelling inferences about engineering, specifically.

4 ANALYSIS

The synthesis process of our gathered papers was organized in two phases. Phase 1 (Section 4.1) focused on analyzing the articles using deductive codes derived by the core authors from reciprocity orientations. In addition, our Phase 2 analysis (Section 4.2) focused on examining the collaborative memos that were generated during the article analysis. The outcomes of the article and memo analyses revealed a need for further interpretation, particularly around the extent to which the codes alone could provide insights into the extent of reciprocity present within SLCE efforts. Therefore, using the collective findings from our article and memo analyses, we developed a second dimension to interpret the levels of reciprocity in SLCE literature. We used these two dimensions (deductive codes and levels of reciprocity) to establish an emergent analytical framework for evaluating the articulation and extent of reciprocity found in SLCE efforts.

4.1 Phase 1: Coding

In this section, we present the development and piloting of our codebook, as well as the implementation of deductive codes to analyze the gathered articles.

4.1.1 Developing codebook using reciprocity orientations

To code the dataset derived through our article selection process, we developed a priori codes (Saldaña, 2015) to operationalize Dostilio et al.'s descriptions of the reciprocity orientations. By deconstructing the complex orientations into codes, we were able to methodically analyze our dataset for elements of reciprocity within the SLCE efforts described.

The core author team derived the a priori codes through distilling each of Dostilio et al.'s orientations (exchange, influence, generativity) into key observable characteristics, as shown in the “Deductive codes” column in Table 2. Initial codes included “impacts,” “knowledge,” “approach,” “relationship,” “context,” and “problem identification.” For example, under the exchange orientation, the description of “give and receive” was interpreted as referring to the impacts and/or benefits received as a result of the engagement. Once the initial set of codes were determined by the core authors, three additional codes were identified during the discussion of the a priori codes as implicitly woven into the orientations and as critical components of reciprocity: “definitions,” “research methods,” and “power, privilege, and oppression.” “Definitions” was added to address the various definitions used to define SLCE efforts and the implications each definition had on reciprocity. “Research methods” was added as a code because the research approaches were a core component of peer-reviewed articles, which made observable characteristics of reciprocity accessible through the way methods were enacted, as well as how units of analyses were determined. Finally, “power, privilege, and oppression” emerged in discussions on the implicit and/or explicit nature of these characteristics in the ways reciprocal partnerships are formed and executed.

| Orientation to reciprocity | Description of orientations as presented in Dostilio et al. (2012) | Deductive codes |

|---|---|---|

| Exchange | “Participants give and receive something from the others that they would not otherwise have. In this orientation, reciprocity is the interchange of benefits, resources, or actions” (p. 19). | Impacts/benefit |

| Influence | “The processes and/or outcomes of the collaboration are iteratively changed as a result of being influenced by the participants and their contributed ways of knowing and doing. In this orientation, reciprocity is expressed as a relational connection that is informed by personal, social, and environmental contexts” (pp. 19–20). | Impacts Knowledge Approach Relationship Context Problem identification |

| Generativity | “As a function of the collaborative relationship, participants (who have or develop identities as co-creators) become and/or produce something new together that would not otherwise exist. This orientation may involve transformation of individual ways of knowing and being or of the systems of which the relationship is a part. The collaboration may extend beyond the initial focus as outcomes, as ways of knowing, and as systems of belonging evolve” (p. 20). | Relationship Knowledge Impacts Problem identification |

4.1.2 Pilot coding session using deductive codes

After we developed the initial deductive codes, the core authors implemented a pilot coding session (Creswell & Creswell, 2017) to systematically align the approach to the analysis across the team. For the pilot coding session, each team member reviewed and analyzed the same sample paper using the deductive codes (Table 3). We also included an additional code, “other,” to inductively capture potential emerging codes by the team during the pilot session. Once each member coded the assigned paper, the full team met to discuss and revise the codes before beginning to analyze the full dataset. Our discussion resulted in no major changes or additions to the initial deductive codes. In Table 3, we document the deconstruction of each reciprocity orientation into the deductive codes, justification for inclusion of each code, and guidance for the operationalization of each code in analysis.

| Code | Dostilio excerpts | Justification of the emergence of each code | Guiding question for analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Context | Dostilio et al. (2012) assert that “reciprocity cannot be separated from individuals, families, communities, and generations or the time or place that provide it context and influence it” (p. 24). | Context was derived as an element of our framework based on the importance of situating SL/CE efforts within the particular circumstances of each partnership. The salience of issues related to who, what, when, and where highlight how the students, university, and community enter and maintain relationships. Context is closely related to all other framework elements, as it shapes stakeholder engagement, relationships, and project outcomes. In this case, since SL partnerships involve multiple contexts, we coded for university, community, and student. | How is context described?

|

| Approach | Dostilio et al. (2012) argue that a “particular consideration for analysis” is that “reciprocity can be present within a process, an outcome, or both; further, it can actually be a process or an outcome of engagement” (p. 24). | The processes, including the approaches that partners take to initiate and engage in a project, are an important analytic consideration of reciprocity. A closer examination of the steps and actions of the processes involved in approaching a partnership provides a way to understand reciprocal work. | What are the steps and actions taken to initiate, engage, and complete the SL/CE effort? |

| Problem identification | Generativity-oriented reciprocity is characterized by processes “that include the co-definition of issues to be addressed” (Dostilio et al., 2012, p. 26). | SL/CE efforts are initiated when stakeholders problematize an area of focus. Therefore, problem identification was identified as a critical framework element. The way universities, students, and communities are involved and the extent of their involvement in problem identification are reflective of different orientations to reciprocity. | How are community needs that are being supported by the SL/CE effort identified? |

| Impacts | Exchange-oriented reciprocity is implicated, as participants are involved in a straightforward “interchange of benefits, resources, or actions” (Dostilio et al., 2012). | As noted in the Approach framework element, both processes and outcomes are analytic considerations in determining the form and extent to which reciprocity is present in each partnership. The impacts, or outcomes that are achieved, range from the interchange of resources (exchange-based reciprocity) to the transformation of systems (generativity-oriented reciprocity). Impacts were coded at the student, university, and community levels to more closely examine how outcomes affected stakeholders. | What are the impacts on stakeholders?

|

| Knowledge | Dostilio et al.'s (2012) reference to “ways of knowing” in defining influence- and generativity-oriented reciprocity (pp. 19–20). Additionally, as Dostilio et al. (2012) note, reciprocity “is also relevant to the knowledge products created” (p. 28). | Knowledge was developed as a framework, as it represents a form of currency in reciprocal relationships and includes the ways in which information is generated, exchanged, and shared among stakeholders. Therefore, this framework element also included a consideration of the types of knowledge that were produced through each partnership. | How is knowledge created? Who is creating the knowledge? How is knowledge being shared? |

| Relationship | Dostilio et al. argue that reciprocity in the SL/CE literature is “viewed as relevant in relationships between the full range of individuals and organizations” (p. 20). Further, Dostilio et al. describe the concept of reciprocity from a generativity-oriented perspective as the “interrelatedness of beings and the broader world around them as well as the potential synergies that emerge from their relationships” (p. 24). | Reciprocity can be expressed through collaboration and relational connections among stakeholders (Dostilio et al., 2012). Therefore, relationship was developed as an element of our framework. These relationships manifest differently depending on the orientation to reciprocity. The way authors report the roles of stakeholders in SL/CE projects and represent their relationships provides insight into how reciprocity is being attempted and enacted. | What is the relationship among stakeholders? |

| Power, privilege, and oppression | Partners are embedded in systems that influence differences in identity, privilege, and ways of knowing (Dostilio et al., 2012). | Power, privilege, and oppression was an element that cut across all other framework components. The way stakeholders are positioned, how areas of focus are problematized, and the way relational connections are established and maintained speak to issues of power. The conceptual review on which this framework is based points to the importance of considering reciprocity within systems of power. These elements must be reflected upon in order to provide specificity about the ways reciprocity are expressed in a partnership. | In what ways are power, privilege, and oppression implicitly or explicitly considered? |

| Research methods | N/A | After an initial mapping of Dostilio's orientations into operationalized codes, our team met. Our iterative discussions led to an additional framework element, Research Methods. The systematic steps documenting SL/CE projects and outcomes were determined to be an important indicator of reciprocity. Processes regarding the selection and implementation of research methods foregrounds different stakeholders' interests. For example, community-based learning, community-based participatory research, and other action research approaches have the potential to be generative and transformative, as a result of the fundamental principles that underlie these forms of research. Methodological choices and rigor contribute to the forms of reciprocity that are enacted. | How are research methods described? |

4.1.3 Analysis cycle using deductive codes

The full set of articles were analyzed with the deductive codes documented in Table 3. This coding cycle involved assigning each article to two reviewers, where each reviewer analyzed the article independently using the deductive codes. Reviewers employed guiding questions that broke down the concept of each code, enabling them to identify elements of the codes in the articles (guiding questions can be seen in Table 3). Once the coding was complete, each article and the corresponding analysis were discussed by the two reviewers who analyzed them. These discussions were captured in collaborative memos, which then provided the analysis artifacts that served as the foundation for Phase 2 of our analysis.

4.2 Phase 2: Developing emergent analytical framework for reciprocity

This section presents the analysis of the collaborative memos for each framework element and the levels of reciprocity practice that surfaced from the analysis.

4.2.1 Analysis of collaborative memos

Once the team of two reviewers completed their independent coding of shared articles in Phase 1, Phase 2 of the analysis included two cycles of exploring the resulting collaborative memos. This was done to capture additional insights from the memo to enrich understanding of how reciprocity was articulated across the articles. The first cycle of analyzing the memos involved developing analytical templates to guide our analysis and to ensure consistency across reviewers. The template included definitions for each of the deductive codes and space for the reviewer to describe characteristics, trends, and exemplars present in the collaborative memos. To allow for flexibility in this cycle of the analysis, reviewers were also asked to capture any emerging analytical observations related to the codes. Each reviewer was assigned a specific code for further analysis (e.g., Author 3 was assigned the “problem identification” code). The authors then analyzed the collaborative memos for their assigned code independently, with the goal of identifying more nuanced insights on the code.

For the second cycle, the authors then met in teams of three to discuss the findings resulting from the first cycle of analyzing the memos. Each team included one member who had performed the analysis of the assigned code and two members who had not. These discussions aimed for consensus on findings and fostered deeper reflection on trends and descriptions.

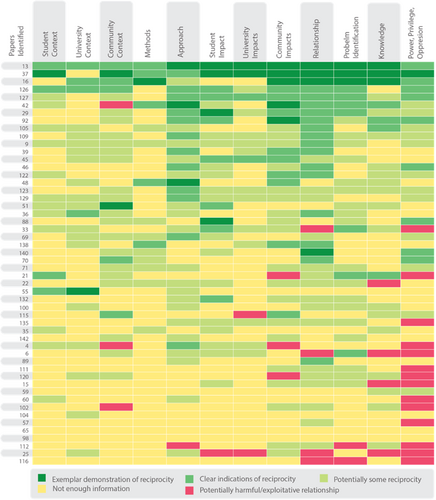

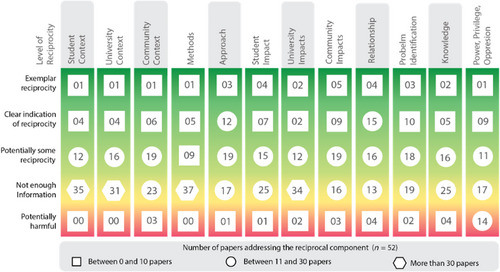

Throughout the analysis of the memos, the authors identified that the memos presented varying levels of reciprocity depending on the extent of orientation elements being present in the descriptions of the SLCE efforts. From the process of analyzing the articles, we recognized that the deductive codes alone did not capture the breadth of practice related to reciprocity. We explored this idea further by constructing a two-dimensional framework. This framework (a matrix of the codes in Table 3, and levels in Table 4) captures the articulation of reciprocity in SLCE efforts, as well as facilitates identifying the level of reciprocity practice.

| Level of reciprocity | Rank | Description of each level |

|---|---|---|

| Potentially harmful/ exploitative relationship | −1 | Scenarios that show potential for harm, whereby the community partnership was leveraged strictly for the gain/benefit of the university stakeholders. |

| Not enough information | 0 | Scenarios in which not enough information was present within the reviewed manuscript to determine the extent of reciprocity present. |

| Potentially some reciprocity | 1 | Scenarios in which there is indication of community stakeholders' involvement and benefit, even if it were minimal. |

| Clear indications of reciprocity | 2 | Scenarios in which there is evidence of community stakeholders' recognition, participation, and impacts in deliberate ways from a moderate to a high level. |

| Exemplar demonstration of reciprocity | 3 | Scenarios in which community stakeholders are well-integrated across the framework components at a very high level in relation to the papers reviewed. |

- Note: Colors used in table are shown to match the colors of the levels of reciprocity used in the heat map in Figure 2.

4.2.2 Early stages of analytical framework development

Our analysis in Phase 2 focused on examining the collaborative memos from the lens of understanding how the codes informed the form and extent of reciprocity in engineering SLCE (addressing RQ2). This analysis revealed new perspectives on the wide range of reciprocity practices, and we found that leveraging the deductive codes alongside these levels of practice could function as a framework for understanding, evaluating, and informing the manifestation and extent of reciprocity.

For example, we initially derived the element of “context” based on the centrality of time, place, and the people involved in an SLCE partnership: “reciprocity cannot be separated from individuals, families, communities, and generations or the time or place that provide it context and influence it” (Dostilio et al., 2012; p. 24). The salience of context—who, what, when, and where—highlights circumstances influencing how the students, university, and community enter and maintain relationships. However, through further analysis of the memos, we found that context also informs and connects to all other elements of reciprocity because it shapes stakeholder engagement, relationships, and project outcomes.

During the Phase 2 analysis discussions, we identified that the extent to which reciprocity elements were present in an article was indicative of a level of reciprocity. This observation took shape into a gauge for allowing us to interpret whether a partnership was exploitative or an exemplary demonstration of reciprocity. Table 4 presents the levels that were extracted from the discussions on the Phase 2 analysis, along with a ranking scale that would be used to understand the levels of reciprocity present in the articles we reviewed.

The collaborative memos for each code were evaluated using the ranking system in Table 4, independently by two authors. The authors began by analyzing two memos and then met to check for reliability of their approach to assigning levels of reciprocity. Any text that indicated harmful or negative implications, such as downplaying the community outcomes, in the cell was coded as −1. Any text that either was blank (no data) or mentioned that not enough information was included that would indicate reciprocity was coded as 0. Text that suggested reciprocity was present and/or the community was involved, would benefit, or was impacted/changed to any extent at all, even minimal, was coded as 1. Clear language of reciprocity (shared, involved, collaborative, etc.) was coded as 2. Lastly, in cells where there was an exemplary level of reciprocity with respect to the other papers/framework elements, we coded as 3. In cases where the two coders disagreed, they met to discuss each cell of disagreement, and negotiated a consensus when possible. This ultimately led to an interrater reliability score of 99.2%, where agreement was not possible on only 5 of the total 676 cells. The outcome of this analysis is illustrated in Figure 2 and interpreted in Section 6.

4.2.3 Authors' note on analysis of articles

Our analyses are based on the language used by the authors of the reviewed articles to report or make claims about what was involved in their SLCE efforts. The authors of this article agreed that a paper with an absence of evidence under a specific code—for example, “knowledge” or “impacts”—does not mean it indicates an absence of knowledge-sharing or mutual benefits in their respective SLCE; rather, it just might mean that it was not reported or emphasized in the final paper. We acknowledge the prioritization of demonstrating the value systems related to student and university outcomes at institutes of higher education. Because of these values, we therefore further recognized that papers might be limited in presenting evidence of particular themes. For example, Aslam et al. (2014) report that the students and the community co-created knowledge in the SLCE work through appreciating the expertise from both sides. We cannot access the perspectives of participants on all sides of this interaction, but we do know the authors valued the co-creation of knowledge between the students and the community in the relationship because they chose to report it in the article. During the analysis, such value statements are either explicitly described by the authors or are implicit, thus requiring interpretation during the data analysis.

5 FINDINGS

We operationalized Dostilio et al.'s orientations for understanding reciprocity in SLCE into eight codes. This section presents our findings across each code, in sequence, addressing how each contributes to answering RQ1: In what ways is reciprocity articulated in the literature of engineering SLCE? We start by defining the way authors across the engineering SLCE literature articulate content that aligns with each code. After defining the code, we then present the primary characteristics, using examples from each code, while pointing to the trends that were found within each of these emergent characteristics. These findings are summarized in Table 5.

| Code | Definition | Characteristics | Categories |

|---|---|---|---|

| Context (student, university, community) | The specific placement of the SL effort, including the people, places, time, and environment that circumscribe the SL | Balance of focus | 1. An institutional context-focused study (prioritized the university, the university students, and their evolution); 2. Student outcomes and classroom-focused; 3. Community solution/product focused; 4. Long-term context development/integration focused |

| Depth of description | 1. Descriptions constrained to one or more of the above foci; 2. Description of partnership |

||

| Emphasis on history, organizational operations, site, or people | 1. No description; 2. Description included | ||

| Research methods | The way in which the systematic steps documenting the SL and its monitoring of success were shared | Type of method | 1. No description of method; 2. Vague description of methods; 3. The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SOTL); 4. Mixed/multi-method approaches; 5. Case study; 6. Participatory methods |

| Focus of methods | 1. Students; 2. University; 3. Community; 4. Entire SL partnership | ||

| Rigor/quality of application | 1. High-quality Research Methods; 2. Absence of high-quality methods | ||

| Approach | The steps taken to initiate the collaboration, the process followed to build the partnership, and the milestones on the way to achieve the outcomes intended from the SL efforts | Descriptions of approach to the SLCE | 1. Informal and formal integration of SL into the curriculum; 2. Multiple stakeholder involvement in various stages of the SL effort; 3. Efforts taken by university to build international service-learning partnership |

| Impacts | The achieved outcomes described in the reviewed papers | Distribution of impacts/outcomes across stakeholders | 1. Impacts on students were the most frequently described; 2. University and student impacts were most often the driving factor behind establishing SL partnerships and experiences; 3. Community impacts were often implicit and largely described from the perspective of the authors |

| Relationship | The way the authors report the roles of stakeholders within the SL efforts | Descriptions of relationships within the SLCE | 1. Relationships were reported in a student-centric and task-oriented way; 2. Relationships were facilitated through formal ways of interacting with all stakeholders; 3. Relationships were mutually beneficial, collaborative, and multilateral between multiple stakeholders in CBL/SL efforts |

| Problem identification | How stakeholders determined the issue, project, or course goals that were addressed by the SL effort | Extent to which multiple stakeholders are authentically involved in identifying problems to be addressed via SL | 1. One stakeholder is the primary influence; 2. There is minimal collaboration among the stakeholders; 3. Intermediary organizations support decision making; 4. A systematic, multistakeholder approach is pursued |

| Knowledge | The ways in which information was identified, exchanged, and generated as a result of university–community engagement and its programs | Types of knowledge | 1. Process and product knowledge; 2. Knowledge of community; 3. SL programmatic and theoretical knowledge; 4. SL course/program content and design knowledge |

| Loci of control/ownership/creation of knowledge | 1. Knowledge generated and controlled by Faculty and/or students; 2. Community partners as providers of feedback within knowledge generation | ||

| Power, privilege, oppression | The ways in which perceptions of stakeholders, their actions, and ways the language used to describe these indicate privileging or increased authority of one stakeholder over another | Distribution of Power across Stakeholders | 1. Students hold more power than community partners; 2. Students and Faculty hold power; 3. Students hold more power despite efforts to empower community; 4. Efforts taken to empower the community; 5. Community as empowered partners; 6. Power retained by community |

| Power conveyed through language | 1. Subtle language queues that disempower the community; 2. Language queues that promote equitable consideration of power; 3. Language that reflected priorities within the SLCE context | ||

| Control and access to resources | 1. Funding |

In this paper, it was necessary that we critique the content reported within the engineering SLCE efforts. We recognize reciprocity is a challenge, difficult in practice, and easy to critique. Therefore, we decided to only explicitly cite and name exemplars of reciprocity, while examples of low reciprocity and exploitation are only alluded to in aggregate.

5.1 Findings: “Context” code

Through our analysis of the articles, data coded within context was defined by the conditions of the SLCE effort, including the people, places, time, and environment. We further delineated context into three primary subcodes to align with the SLCE stakeholders: student context describes the backgrounds and circumstances of the students; university context describes the characteristics of the university and relevant units within it that concern the SLCE efforts; community context describes the environment in which the SLCE effort is carried out and the circumstances of the associated community partners.

Across the reviewed articles, we found that there were three main characteristics used by authors when articulating contexts: (i) balance of focus across stakeholders; (ii) depth of description; and (iii) thematic emphasis on history, organizational operations, sites, or people.

Within balance of focus across stakeholders, four categories emerged across the articles (Table 5): (i) an institutional context-focused study (prioritized the university, the university students, and their evolution); (ii) student outcomes and classroom-focused; (iii) community solution/product-focused; (iv) long-term context development/integration-focused.

Studies where the balance of focus prioritized the institutional context focused on how the SLCE effort benefited the university, such as the alignment and justification of the course and outcomes with ABET accreditation. Participating universities were often large (and frequently land-grant) public institutions. Descriptions of instructors were often limited to describing the instructors' perspective, their role/lectures, and overall course goals. The curriculum was described alongside a history of SLCE at the university (focusing on justification for the course and procurement of financing). Few studies were part of ongoing courses (those that were, were typically associated with the EPICS program), and these more often had ethics outcomes and the trajectory of the classes described. Again, the course context was typically not a required core course but rather a cornerstone or capstone design course and/or elective. Sustainability of the course was discussed here, as the course may have been designed to meet institutional initiatives (e.g., connecting with an industry/company partner for corporate benefits), the university mission (e.g., Jesuit tradition), and organizational membership. The context referenced the leveraging of institutional commitments, resources, and connections. For long-term SLCE course maintenance, institutional commitments were present (and perhaps required).

Studies with a balance of focus placed on the student context were often nested in the university, where most examples primarily focused on the context of the SLCE course learners. Student leadership was limited (typically not leading the design or decision making of the course). Some were given specific responsibilities (e.g., within a budget), milestones, and requirements for communication with community partners. Assessments for students typically focused on social orientation and satisfaction, but they gave limited descriptions of the students' demographics (e.g., reporting gender, but not race, ethnicity, or ability status). Students often had limited technical experience, and they could take the class to get some practical technical knowledge. Students were often new to service learning, seeing it as an opportunity to volunteer. The student context was isomorphic with the institutional context, in other words, parallel to the aims and behaviors of the institutional context.

The balance of focus placed on a community context was reported least frequently of the four categories that emerged, even at times when university and student context were described extensively. The community context was typically introduced with a superficial description of the people but a detailed geographic description. Often these context descriptions were from a deficit perspective, positioning the community as needs-focused, targeting rural poverty infrastructural issues (e.g., food–water–energy nexus). Some studies distinguished the wider community and local partner non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The NGOs were often already working with the communities, which sometimes separated direct communication between the university/students and the community partners. However, when deeply embedded and committed to the community, the NGOs also facilitated reciprocity among all partners. A few of the studies were situated within a domestic context working with community partners in the United States. We found that, more frequently, the SLCE partnerships were cross-national engagements, which can afford the benefits of building global competence and broadening university students' social, political, and cultural understandings of engineering work (Salam et al., 2019). However, this kind of engagement can also position the community partners as “other,” flattening understandings of complex social and historical factors, such that students can easily identify inequities in other cultures, but not in their own.

The additional two characteristics used to describe the contexts across articles include the depth of description and the thematic emphasis on history, organizational operations, site, or people. Overall, nearly every article had some description of the context of their work, although a handful focused more on describing the nature of the partnership rather than the partners' contexts. The context description in most articles often situated the SLCE in space, geography, time, goals, and values.

The relationship between the various stakeholder contexts—student, university, community—pointed to how a whole study could be characterized: following Dostilio et al., contexts described in the studies as either generative or characterized by a combination of exchange and influence. Examples of coding for context that were supportive of reciprocity include always mentioning the community site and providing background history and efforts to develop sustainability for the SLCE effort and reciprocal relationship. Elements that were not supportive of reciprocity include superficial descriptions of the community, focus on institutional history/mission, and emphasis on university students. Such elements were “necessarily” often a deficit of focus, seeing reciprocity as a clear exchange. Generative reciprocity contexts included descriptions of all relevant resources and motivations across all three stakeholder groups that are very detailed. Participants from the university as well as the community are described in extensive and human detail, explaining their goals and motivations. In contrast, exchange/influence reciprocity relations are often aligned with “service” orientations, and the U.S. institutions (whether the student or university units) are described in operational detail. The community is described superficially and as “in need.”

5.2 Findings: “Research methods” code

The reviewed articles articulated “research methods” in ways that led us to develop the following definition: the systematic steps documenting the SLCE effort and the ways of monitoring of success/outcomes/impact. This definition agrees with broad understandings of appropriate program evaluation, learning, and reporting (e.g., USAID, 2022). We recognize that methodological choices in manuscripts can vary significantly, and therefore our analysis focused on the ways authors described their methods, without limiting to a particular methodological approach. In our review, three relevant characteristics emerged: (i) the type of method, (ii) focus of the methods, and (iii) the rigor/quality of the application of the methods.

The most prevalent category of methods types was “no description of research methods”, where 12 articles did not explicitly share how they documented, monitored, or made inference about the SLCE effort (see below for further discussion of gaps in rigor). In the next largest category, 10 articles used a multi-/mixed methods approach, utilizing multiple strategies for gathering information. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SOTL) papers and surveys were, respectively, each identified in six articles; methods used but not explicit enough to categorize, as well as qualitative or interview methods were used in five studies; and case study methods were used in four. Given the range of methodological choices we observed in SLCE publications, we discuss in our concluding section the implications for strengthening the investigative approaches within the SLCE space.

Within the focus of the methods category, the unit of analysis within the reviewed articles was most often centered on students, followed closely by the community. We see therefore that the subjects of SLCE in engineering research are most often university students. Further, when a community focus was included as a unit of analysis, these articles still often treated the community like a datapoint, rather than as contributors within a partnership. Very few articles focused on the experiences of the instructors. Some papers focused on describing the structures of the actual SLCE partnership itself (Davis et al., 2014; Kant et al., 2014; Thompson & Jesiek, 2014).

Finally, there was also a range of rigor/quality within the reviewed articles. As we were not evaluating the specific methodological choices themselves, we assessed rigor broadly on the common guidelines for educational research (National Science Foundation, 2013), namely, generating evidence about opportunities for learning or knowledge production. For example, some articles were very rigorous and reported exemplary use of educational research methods (Arcipowski et al., 2017; Stein & Schmalzbauer, 2012). On the other hand, a handful of papers demonstrated little to no methodological quality and/or did not address methods in the article. Papers lacking methodological rigor may have lacked alignment between evidence and design choices or drawn conclusions that involved leaps in reasoning or overinterpretations. Research methods were one of the major gaps identified by our review; the type of method was not always explained, nor was the focus or unit of analysis always explicitly articulated.

Incorporating reciprocity as part of methodological rigor is crucial for equitable SLCE; participatory methods align with reciprocity by involving community partners in the research. The descriptions of a community's participation can indicate whether they were viewed as a data point or full partner. However, SOTL papers frequently do not represent reciprocity because they focus mainly on student teaching and learning, which is oriented toward the university. Therefore, partnership should be considered as part of the methods consideration, including in ethics reviews and peer reviews.

5.3 Findings: “Approach” code

The “approach” across the articles can be defined as the steps taken by the institution and/or the community partner to initiate the collaboration, the process followed to build the partnership, and the milestones on the way to achieve the outcomes intended from the institution–community engagement. Among the articles we reviewed, we captured three main aspects of the approach taken by the three different stakeholders (faculty, students, and community partners) to engage in engineering SLCE activities: (i) informal and formal integration of SLCE into the curriculum; (ii) multiple stakeholder involvement in various stages of the SLCE effort; and (iii) efforts taken by higher education institutions to build international SLCE partnerships as part of a major university initiative or mission.

Most of the reviewed papers focused on SLCE efforts formally integrated into the curriculum. However, the approaches taken to integrate SLCE experiences into undergraduate engineering education differed in terms of the target audience and the types of models for integration. Engineering SLCE courses were offered as one-credit courses (often offered to first-year students), project-based learning elective courses, summer study abroad programs, and senior capstone projects (e.g., Abrahamse et al., 2015; El-Gabry, 2018; Onal et al., 2017; Seay et al., 2016). Most of the SLCE experiences were offered as multidisciplinary courses to students from various disciplines in engineering and technology. Some of the articles reported SLCE experiences integrated as informal extra-curricular activities led by non-profit/student organizations such as Engineering for Sustainable Development and Engineers Without Borders (Chisolm et al., 2014; Florman et al., 2009; Stein & Schmalzbauer, 2012).

Another category that emerged via review of the approach to SLCE was the involvement of multiple stakeholders at various stages of the SLCE efforts such as problem identification, design, development, testing of solutions, and final implementation within the community. Most of the partnerships were initiated by the university, while some were initiated by the community partners themselves. There were also a set of articles that were initiated by nonprofit organizations who acted as intermediate facilitators between the university and community. Few articles showcased a comprehensive multi-stakeholder, participatory approach where the faculty, students, and members from the community interacted and jointly collaborated throughout different stages of the SLCE effort (Aslam et al., 2014; Dunkel et al., 2011; Kang & Chang, 2019; Reynolds, 2019; Trott et al., 2020).

The last trend observed was the international nature of many of the SLCE efforts, where many included an international component where the problems to be addressed were identified from different countries, especially from lower income nations (Abrahamse et al., 2015; Budny & Gradoville, 2011; Reynolds, 2019; Seay et al., 2016; Simon et al., 2012). Some articles recognized the importance of building cultural awareness among students before visiting international community partners and organized capacity-building sessions to bridge these gaps. For example, Simon et al. (2012) described a direct correlation and impact of improving cultural awareness and constant communication with international partners to the partners' level of ownership and buy-in to the SLCE efforts. Many articles described the logistics and challenges involved in organizing international SLCE efforts where most of the community interaction occurred as part of summer study abroad or a short immersion experience.

Our analysis observed that the extent of reciprocity can be examined via the approach and the extent of stakeholder involvement at various stages of the SLCE effort. Approaches were considered least reciprocal when the students had no interaction with the community partners and worked to solve pre-identified problems provided to them by the faculty. Here, the SLCE efforts were completed within the boundaries of the university and therefore had limited elements of reciprocity within the entire experience. The extent of reciprocity was observed to be more involved in articles where the problems being addressed were identified and provided to the university by the community partner. In this type of approach, the community partner may have had greater, but still limited, involvement in the entire process. Further reciprocity was showcased in SLCE efforts where students actively engaged with community members, contributing to the development of meaningful relationships between the stakeholders. The most thorough form of reciprocity was highlighted in articles that reported following a systematic and/or participatory approach during all the various stages of the SLCE effort. Within these approaches, there appeared to be attempts to build a long-term partnership with the community through frequent face-to-face interactions that can allow the development of trust, respect, and meaningful relationships between the stakeholders.

5.4 Findings: “Impacts” code

Impacts, defined as the outcomes achieved for each of the stakeholders involved in the SLCE partnership, were observed to cluster across three sets of characteristics, similar to the three sets for context. As with the context code, these three areas of impacts—student, university, and community—were further delineated to align with the three stakeholders: student impacts describe the outcomes and benefits directed at students; university impacts describe the impacts associated with the university and relevant units within it that concern the SLCE; community impacts describe the benefits and outcomes directed at community partners. The analysis of the impacts explored the implicit and explicit outcomes of the SLCE efforts described by the authors and resulted in three trends across the reviewed papers: (i) impacts most frequently centered students; (ii) university and student impacts were most often the driving factors behind developing SLCE partnerships and experiences; (iii) community impacts were often implicit in the reviewed papers and were generated from the perspective of the authors.

The first trend we observed was that, in describing outcomes of the SLCE effort, impacts most frequently centered the outcomes achieved by the students. The primary areas of impact on students were the technical and professional skills that were developed. In the reviewed papers, impact was evaluated using techniques such as pre and post surveys (e.g., Budny & Gradoville, 2011) and guided reflections (e.g., Florman et al., 2009), which were most often used for the purpose of assessing student learning outcomes. Moreover, the evaluation techniques predominately focused on learning outcomes associated with technical skills (i.e., problem-solving and engineering design), while professional skills (i.e., cultural competency, leadership, communication) were often not explicitly evaluated, but an assumed outcome of the immersive nature (i.e., cultural, geographic) of the SLCE experience.

The second trend that emerged from analyzing the impacts of the reviewed papers suggested that SLCE efforts were developed to fulfill the need of achieving specific outcomes for universities and students. Across the reviewed articles, the primary need identified was to provide experiential learning opportunities for students. Some papers alluded to unassessed long-term university and student impacts, such as graduating students who were giving back to society more broadly. The impacts on the universities varied, but largely focused on increasing access to funding opportunities, positive media and public exposure through curricular advancements, an enhancement to recruitment and retention efforts, and vague or watered down allusions to broader impact that align with societal benefits.

The third trend revealed that there were few instances where community impacts were described, and even fewer where these impacts were centered. Further, when impacts on the community were described, they were written from the authors' perspectives rather than collected from the community perspectives themselves. The most common community outcomes that authors did include tended to make assumptions of positive outcomes for the community by nature of the service students provided (e.g., community will benefit from having a product installed for them), the product of the engineering design project, community being educated on engineering topics broadly or on the specific product or service being provided, or community being empowered to use the installed product. Lastly, impacts on communities were not prioritized by authors when providing a description of the overall SLCE efforts. This outcome could be a result of the value systems at institutes of higher education, as mentioned earlier in the paper. However, this could also be a result of not centering community perspectives when approaching the design of a SLCE effort, particularly the evaluation aspect of the effort. Only two of the articles (Davis et al., 2014; Stein & Schmalzbauer, 2012) intentionally collected feedback from the community partners as evidence for the community impacts that were described in the paper.

When considering the findings of the impacts code through the lens of reciprocity, characteristics of mutuality in the partnerships could be inferred, but not confirmed, in some cases by observing how and in what ways impacts were framed and prioritized in SLCE efforts. For example, when the impacts only focused on student and/or university outcomes, it is possible that community impacts were not considered, or only seen as a byproduct at the conclusion of the student service experience. This inference can indicate an exchange orientation of reciprocity, where student learning is one of the impacts of the service and the community also experiences an impact from the service, resulting in a direct exchange of benefits during the experience. However, when community perspectives are excluded from the evaluation of the impacts of a SLCE effort, there is a risk of actions from students and universities that could produce negative outcomes on the community. These outcomes could undermine reciprocity, resulting in an imbalance in the exchange of resources, inauthentic relationships, and a partnership lacking transformative outcomes for the partner community.

5.5 Findings: “Relationships” code

In our review, coded data highlighting relationships addressed how the authors (from university or community) describe the roles of stakeholders (university, students, faculty, programs, community) and their interactions with each other. For example, we observed the form and frequency of communication between student design teams and users/clients in the partner community site. Three trends emerged in the literature when describing the relationships within SLCE: (i) relationships were reported in a student-centric and task-oriented way; (ii) relationships among all stakeholders were established through organized interactions; and (iii) relationships were mutually beneficial, collaborative, and multilateral between multiple stakeholders in SLCE efforts.

The first category includes articles where the authors reported the relationship in a student-centric and task-oriented way. Here, the content in the articles suggests these relationships were formed to facilitate student learning outcomes. For example, in one case, students were engaged in relationships with beneficiaries who served a supporting role in the student-centric goals of learning a technique, process, or approach. In other studies relationships were often established to exchange the benefits of learning outcomes and to finish projects. Furthermore, the community is often described as a “beneficiary,” indicating a distance and distinction in the relationship between the students and the community as provider and receiver.

The second category lends insight to articles where the authors reported the relationship by mentioning formal ways of facilitating interactions among stakeholders (primarily students and community partners). In these interactions, for example, formality was introduced by generating a list of the stakeholders, roles, or responsibilities involved in the SLCE efforts (e.g., Chisolm et al., 2014). Additionally, a structured approach for fostering relationship-building was implemented through organized meetings, rather than having students engaging with the community in spontaneous ways. For example, Onal et al. (2017) describe formal meetings initiated when the instructor visited the local community organizations where student teams could observe the challenges associated with the projects firsthand and discuss possible solutions with local community leaders. The project teams then continued meeting with the community organizations to share their suggested solutions and implement the agreed-upon revisions. As a result, the project teams and the community developed relational connections, facilitating conversations and promoting deeper relationships through regular communication, and using meetings as formal spaces for interacting.

The third category of articles includes content where the authors report relationships to be mutually beneficial, collaborative, and multilateral between SLCE stakeholders. In this category, the key purpose of such a relationship is to support both university and community goals. These efforts recognize that SLCE cannot exist without community buy-in and collective engagement. For example, Bratton (2014) acknowledges that their global program is only made possible through relationships in which “students learn to see ‘clients’ as ‘partners’ without whose cooperation, the solutions created, no matter how innovative or affordable, would be less likely to succeed in the long-term. The needs of partner organizations must be satisfactorily addressed for the relationship to flourish and the project to advance” (p. 207). The value of understanding such purpose is to facilitate the students' appreciation of knowledge from the community and enable all stakeholders to feel a part of and contribute to the project.

To summarize, the ways relationships are approached and described may reflect the authors' intentions to support reciprocity. If the relationship is positioned as student-centric and task-oriented, it can be challenging to determine how reciprocity is present via this framework element. Our analysis suggests that, in addition to investing time and approach, partners may authentically and systematically structure relationships through formal interactions and also invite mutual engagement and increased levels of reciprocity. Similarly, mutually beneficial, collaborative, and multilateral interactions among multiple stakeholders in SLCE efforts embody highly reciprocal relationships (DeBoer et al., 2022; Delaine et al., 2023).

5.6 Findings: “Problem identification” code

Data coded under problem identification led us to define this code as how stakeholders determined the issue, project, or course goals that were addressed/pursued by the SLCE effort. Problem identification existed along a continuum that involved varying degrees of collaboration among stakeholders. Some papers described how projects were selected, yet omitted who was involved in the selection process. These articles provided little insight into how the project's focus was determined and which stakeholders were involved. In other cases, when problem identification was described, it could be differentiated into four categories.

Through our data analysis, four categories of problem identification emerged: (i) one stakeholder is the primary driver of problem identification; (ii) collaboration among stakeholders to identify problems is evident, but limited; (iii) external stakeholders, such as intermediary organizations, drive problem identification; and (iv) problem identification is derived through a systematic, multi-stakeholder approach.

In the first category, one stakeholder was the primary influencer when determining what problem to address, even if opinions of other stakeholders were solicited. For example, Onal et al. (2017) described a partnership in which either students or the community independently submitted industrial engineering projects ideas to faculty members, who ultimately decided which projects to focus on in the course.

A second category emerged when there was some input from multiple stakeholders in identifying the problem. In these cases, there was community involvement or co-development in the generation and selection of projects. For example, university faculty and engineering students collaborated with middle school principals and students to propose new projects (Anderson, 2005). In a similar effort involving multiple stakeholders, Dewoolkar et al. (2009) involved the community and university faculty in the scoping stages of the project, in which problems were identified to also align with the aims of the course and requirements of the university.

External or additional input, such as the involvement of intermediary organizations or community-based research, represented the third category of problem identification. NGOs connected communities with university partners or provided insight into what local needs the SLCE effort might address. In their work with an Egyptian squatter village, an NGO provided information about which projects might benefit the children in the community (El-Gabry, 2018). Market research and needs analyses also contribute to identifying significant problems for the community. Arcipowski et al. (2017) described the identification of the problem of access to clean water through input from the community and research, which indicated that this issue substantially impacted the community.