Agricultural Lands as Important Wintering Habitats for the Critically Endangered Yellow-Breasted Bunting in Nepal

尼泊尔农业用地作为极危黄胸鹀的重要越冬栖息地

Editor-in-Chief: Binbin Li

Handling Editor: Peng Liu

ABSTRACT

enAgricultural intensification is considered detrimental to many bird species in Europe and North America; however, little is known about how birds use these landscapes in South Asia, including in Nepal, where agricultural lands remain less intensified and more heterogeneous. Compared to resident species, research on migratory land bird species is notably limited. This includes the Critically Endangered Yellow-breasted Bunting (Emberiza aureola), once abundant but now on the brink of extinction due to illegal trapping and trade, particularly along its migratory routes and wintering sites. We studied the wintering distribution sites, population, and fine-scale habitat use of the Yellow-breasted Bunting across Nepal to support their population recovery and guide habitat conservation efforts. Between 2015 and 2023, we documented 85 presence records of Yellow-breasted Buntings in 22 districts, with most sightings occurring outside protected areas and in agricultural lands. The population count for 2022/2023 was 2120—a roughly 43% increase from the previous year. Fine-scale habitat data showed that most sightings were in agricultural lands (79%), followed by grasslands (14%), with fewer records occurring in wetlands (7%). Yellow-breasted Buntings feed in a range of farmland conditions, including standing crops and fallow fields, and roost mainly in agricultural areas dominated by sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) or in grasses such as Saccharum spontaneum and Phragmites karka found in grassland and wetland habitats. Our model identified the combination of crop cover and grass height as the strongest predictor of Yellow-breasted Bunting abundance. Our study highlights the conservation potential of agricultural lands for highly threatened species and emphasizes the importance of effective habitat management and farmer engagement.

摘要

zh农业集约化被认为对欧洲和北美的众多鸟类物种具有负面影响;然而, 在农业活动相对不那么集约、景观更具异质性的南亚地区 (包括尼泊尔), 人们对鸟类如何利用这些景观的认知仍较为有限。相比留鸟, 对迁徙性陆栖鸟类的研究尤为匮乏, 其中包括极危物种黄胸鹀 (Emberiza aureola) 。该物种曾广泛分布, 但因迁徙路线及越冬地非法捕捉与贸易而濒临灭绝。为了支持其种群恢复并指导栖息地保护策略, 我们在尼泊尔开展了关于黄胸鹀越冬分布、种群数量及微观栖息地利用的研究。

2015年至2023年间, 我们在尼泊尔全境22个县记录到黄胸鹀的85个出现记录, 且多数观察发生在保护区之外的农业用地中。2022/2023年冬季种群数量统计为2,120只, 较前一年增长约43%。微观尺度的栖息地数据显示, 79%的观察记录来自农业用地, 其次为草地 (14%) 和湿地 (7%) 。黄胸鹀在多种农田条件下取食, 包括作物成熟期的田地和休耕地, 并主要在甘蔗(Saccharum officinarum)田或草地与湿地中的野甘蔗 (Saccharum spontaneum) 和卡氏芦苇 (Phragmites karka) 等芦苇类植物中夜栖。模型分析表明, 作物覆盖度与草本高度的组合是预测黄胸鹀丰度的最强变量。本研究凸显了农业用地对极度濒危物种的保护潜力, 并强调了有效栖息地管理和农民参与保护的重要性。

简明语言摘要

zh本研究聚焦于黄胸鹀在尼泊尔越冬期间的种群状况与栖息地利用。黄胸鹀因非法捕猎与贸易濒临灭绝, 尼泊尔是其关键越冬区域。2015年至2023年, 我们在22个县记录到85个观察记录, 绝大多数出现在保护区外的农业景观中。2022/2023年种群数量为2,120只, 较上一年增长43%。详细的栖息地数据表明, 79%的个体出现在农业用地中, 14%分布于草地。它们在作物生长期及休耕地中取食, 并主要在甘蔗田和芦苇丛中夜栖。模型分析显示, 作物覆盖度与草高是决定其数量分布的关键因素。农业用地的有效管理及提高农民保护意识, 对于该物种的保护至关重要。

Summary

enWe studied the population status and habitat use of the Critically Endangered Yellow-breasted Bunting in Nepal, a key wintering area for the species, which is now on the verge of extinction due to illegal trapping and trade. Between 2015 and 2023, we documented 85 presence records across 22 districts, with most sightings occurring outside protected areas and in agricultural landscapes. The population count for 2022/2023 was 2120, representing a 43% increase compared to the previous year. Fine-scale habitat data showed that 79% of sightings occurred in agricultural lands, followed by 14% in grasslands. Yellow-breasted Buntings were observed feeding in standing crops and fallow fields and roosting in sugarcane and reed grasses. Our model identified crop cover and grass height as the strongest predictors of their abundance. Effective management of agricultural lands and raising awareness among local people, especially farmers, are essential for the conservation of this species.

-

Practitioner points

- ∘

Regularly monitor population trends and habitat use of the Yellow-breasted Bunting to inform and implement effective conservation actions in agricultural landscapes.

- ∘

Conserve and manage key habitats, including agricultural lands with sugarcane and grass species such as Saccharum spontaneum and Phragmites karka, which are vital for feeding and roosting.

- ∘

Prioritize raising awareness among local farmers about the species' ecology and the threats it faces to support community-based conservation efforts.

- ∘

实践者要点

zh

-

定期监测黄胸鹀的种群动态与栖息地利用情况, 以指导农业景观中的有效保护措施;

-

保护和管理关键栖息地, 包括种植甘蔗以及生长有野甘蔗 (Saccharum spontaneum) 和卡氏芦苇 (Phragmites karka) 等草本植物的农业用地;

-

加强对当地农民关于黄胸鹀生态特性及其所面临威胁的科普宣传, 推动基于社区的保护行动。

1 Introduction

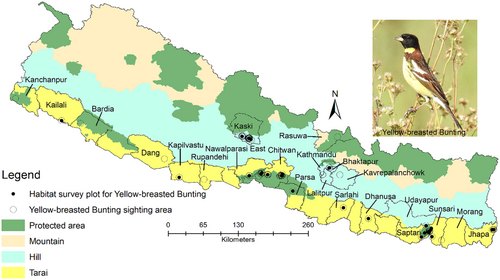

Farmland birds in Europe and North America are experiencing rapid declines (PECBMS 2020; Rigal et al. 2023), primarily due to factors such as crop intensification, excessive use of agrochemicals, hunting and trapping, and land-use change (Rigal et al. 2023; Stanton et al. 2018). In contrast, studies from Asia are limited; however, a recent study from Southeast Asia (Angkaew et al. 2023) also highlights the negative impacts of intensified agricultural landscapes on species of conservation concern, but similar research in the region remains scarce, leaving the effects of these factors on birds largely unexplored. Despite this data gap, more than 25% of bird species in South Asia are known to utilize agricultural lands for foraging and breeding (Grimmett et al. 2016; Katuwal et al. 2022; Sundar and Subramanya 2010). While resident birds have been documented using multi-cropped agricultural lands in South Asia (Katuwal et al. 2022; Sundar and Kittur 2012), there is a significant research gap concerning the use of these landscapes by migratory land bird species, particularly the critically endangered Yellow-breasted Bunting (Emberiza aureola; Figure 1; Inskipp et al. 2016; SoIB 2023).

The Yellow-breasted Bunting is a small passerine bird that breeds mostly in North Asia (Russia), Central Asia (Kazakhstan), and East Asia (Korea, Mongolia, China, and Japan), while wintering in South Asia (Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India) and Southeast Asia (Thailand, Malaysia, Myanmar, Laos, Viet Nam, and Cambodia), at elevations ranging from sea level to approximately 3500 m (BirdLife International 2017; Heim et al. 2024; Kamp et al. 2015; Ly et al. 2022; SoIB 2023). In its breeding range, the Yellow-breasted Bunting occupies a diverse array of habitats, including bogs, meadows, mountain tundra, forest-steppe, broadleaf woods, open conifer forests, clearings, dwarf bamboo bushes, and arable lands such as hay meadows and abandoned fields near villages (Beermann et al. 2021; BirdLife International 2017). However, knowledge about its wintering habitats throughout its range remains limited, although the species has been observed in agricultural lands, shrublands, grasslands, and reed-dominated wetlands (Bhusal et al. 2020; BirdLife International 2017; Katuwal et al. 2022; Saika and Choudhury 2023; Simla 2024). An omnivore, it primarily feeds on invertebrates during the breeding season and switches to seeds, grains, and other plant material at other times of the year (BirdLife International 2017).

The Yellow-breasted Bunting faces significant threats from widespread trapping in both its breeding and wintering grounds, pushing the species to the brink of extinction (Heim et al. 2021; Kamp et al. 2015). Tragically, millions of individuals are trapped and traded during their breeding and migratory periods annually for human consumption and for release in religious rituals (Barca et al. 2016; Chan 2004; Gallo-Cajiao et al. 2020; Gitau and Ngari 2021; Kamp et al. 2015; Stafford et al. 2017; Symes et al. 2018). This intense exploitation has resulted in alarming declines in global populations (Benítez-López et al. 2017; Chan 2004; Kamp et al. 2015; Tamada et al. 2014). Consequently, the species is currently listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List (BirdLife International 2017). Nevertheless, recovery may be possible due to low inbreeding and relatively high genetic diversity (Wang et al. 2022), underscoring the urgent need to identify and protect its habitats.

Nepal, a South Asian country, serves as one of the wintering grounds for the Yellow-breasted Bunting (Bhusal et al. 2020; Inskipp et al. 2016). The wintering population in Nepal may comprise individuals from both western and eastern breeding populations (Heim et al. 2020, 2024), although further studies are needed to confirm this. Once abundant in Nepal during the 1980s and 2000s, the species is now only sporadically observed (Bhusal et al. 2020; Inskipp et al. 2016). Trapping, habitat loss, and pesticide use are believed to be the primary causes of its decline in Nepal, where it is also classified as Critically Endangered in national-level assessments (Inskipp et al. 2016; Katuwal et al. 2023). Currently, little is known about the species' distribution, population structure, or the specific habitats it occupies in winter, nor how vegetation characteristics influence its wintering population. This lack of information has hindered the development of effective conservation policies and actions in Nepal.

In this study, we explore the distribution and status of the Yellow-breasted Bunting in Nepal. Specifically, we aim (1) to determine the wintering population size in Nepal and (2) to describe fine-scale wintering habitat use and understand the factors influencing the abundance of the species. As many passerine birds, including buntings, use agricultural landscapes in Nepal (Katuwal et al. 2023, 2022), we predicted higher occurrences of the Yellow-breasted Bunting in agricultural lands compared to other habitat types. This study provides baseline data on habitat use along the species' wintering grounds and establishes a foundation for future research in other countries across its wintering range.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Area

Nepal is situated between China to the north and India to the east, west, and south. Topographically, the country is divided into three main regions: the Tarai (plains) and hill and mountain zones (Figure 1). Elevation in the country ranges from 60 m to 8848 m above sea level. Vegetation varies across these altitudinal zones: Shorea robusta, Dalbergia sissoo, and Acacia catechu dominate between 60 and 1000 m; Schima wallichii, Castanopsis indica, Pinus roxburghii, and Alnus nepalensis are prevalent between 1000 and 2000 m; Quercus spp., Rhododendron spp., and Juglans regia are common from 2000 to 3000 m; Abies spectabilis, Pinus wallichiana, Betula utilis, and Rhododendron spp. dominate between 3000 and 4000 m; and Juniperus spp. and Rhododendron spp. are characteristic above 4000 m (Dobremez 1976; Shrestha 2008). Rainfall is highest in the east and gradually decreases toward the west. The monsoon season occurs from June to September, with an annual average precipitation of approximately 1600 mm.

Agricultural land accounts for roughly 25% of Nepal's total area (FRTC 2022), with a slightly higher proportion in the hill region, followed by the Terai and mountain regions (Paudel et al. 2017). Rice is typically cultivated across the country during the monsoon season, while mustard, lentils, wheat, and vegetables are grown in winter. Sugarcane, an annual crop, is commonly found in the lowlands and harvested from December to January. Maize is a typical summer crop, although some fields are left fallow after the winter or rice harvest, depending on the availability of irrigation (Katuwal et al. 2022).

2.2 Research Design

2.2.1 Literature Search

The Yellow-breasted Bunting is rare and exhibits a patchy and restricted distribution in Nepal (Bhusal et al. 2020; Inskipp et al. 2016). To gather comprehensive information, we conducted an extensive literature search, including both published and gray literature, using databases such as Google Scholar, and Web of Science. Search terms included “Yellow-breasted Bunting,” “bunting,” and “farmland bird.” We also interacted with local bird experts across Nepal, monitored online databases such as eBird and Facebook, and reviewed all known sighting locations (e.g., Bhusal et al. 2020) to identify possible occurrences of the Yellow-breasted Bunting in Nepal from 2015 to 2023.

2.2.2 Field Data Collection

Based on the identified occurrence sites, we conducted visits to each site 1–2 times per month from November 2022 to May 2023 to monitor population and analyze fine-scale habitat characteristics. To improve the representativeness of habitat data, we extended this study through November and December 2023. The species was not recorded during every visit, despite spending 4–5 h at each site, likely due to its small flock sizes and the presence of some individuals as passage migrants. To determine population size, we visited known roosting sites at sunrise or 1 h before sunset (peak roosting periods) and directly counted the number of individuals present. Because flock sizes were relatively small, we employed at least two observers to minimize double counting and to ensure accurate counts. The population at each site was recorded as the highest count observed in a single day during the survey period, based on either roost or habitat surveys, to account for fluctuations in site usage.

To record habitat variables, we adapted the breeding habitat monitoring protocol developed by Beermann et al. (2021), modifying it to suit the distinct landscape and habitat characteristics of wintering areas in Nepal. For each Yellow-breasted Bunting sighted, we established a 10 × 10 m plot and recorded the exact location using a Garmin GPS (GPSMAP 64 s), along with elevation, habitat type (e.g., agricultural land, grassland, and wetland), soil moisture/habitat conditions (dry, wet, or waterlogged), percentage and height of shrub, grass, and crop cover, and the presence of grazing (yes/no), fire (yes/no), vegetation clearance (yes/no), and trees within each plot (see Supporting Information: File S1).

2.3 Data Analysis

We first compiled all distribution and population data for the Yellow-breasted Bunting from 2015 to 2023. We then calculated the mean (±SE) distance between the plots and the nearest settlement, wetland (all types of water bodies), and agricultural land using high-resolution Google Earth imagery. Descriptive statistics were calculated for the fine-scale habitat use of the Yellow-breasted Bunting collected during our study.

To assess the factors influencing the abundance of Yellow-breasted Buntings in the study area, we used a generalized linear mixed model with a Poisson distribution in the “lme4” package (Bates et al. 2015). We included continuous variables such as cover (shrub, grass, and crop) and their respective heights as fixed effects, with district as a random effect. We performed a multicollinearity test and retained variables with lower correlations (r < 0.7) in the final model, excluding shrub height. Before running the model, we standardized the variables to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 to account for heterogeneity, using the “wiqid” package (Meredith 2022). To address overdispersion in the model, we employed a negative binomial distribution. We assessed spatial autocorrelation in the model using Moran's I test in the “ape” package (Paradis and Schliep 2019), which revealed no statistically significant spatial autocorrelation (p > 0.05). Finally, we ranked models using the Akaike Information Criterion corrected for small sample sizes (AICc; Burnham and Anderson 2002). The relative strength of each model was assessed based on Akaike model weights, using the “MuMIn” package (Barton 2023). Models with ΔAICc < 2 (difference from the top model) were considered the best models. Predictions for significant variables of the best model were generated using the “effects” package (Fox and Weisberg 2019). All analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.2 (R Core Team 2023).

3 Results

3.1 Distribution and Population Structure

We documented 85 presence records of the Yellow-breasted Bunting across 22 out of 77 districts in Nepal, with over two-thirds of these records occurring in agricultural lands. These records spanned one mountain district (highest elevation 3520 m), five mid-hill districts, and 16 lowland districts (lowest elevation 62 m) between 2015 and 2023 (Figure 1). Approximately 59% of these occurrences were outside protected areas. Within protected areas, 31% of sightings were in buffer zones, primarily in agricultural lands, while the remainder were in core areas (Figure 1).

The highest population count for the year 2022/2023 was 2120 individuals across 13 districts, marking a significant 43% increase compared to the previous year (Table 1). We did not record any sightings in Kavrepalanchowk district during 2022/2023, despite documenting them in previous years (Table 1). The mean arrival and departure dates for Yellow-breasted Buntings in Nepal were the second week of October and April, respectively, although some individuals arrived in the first week of October and left by the first week of May. Most of these birds were passage migrants, with some remaining throughout the winter, particularly in Kaski, Sunsari, and Chitwan districts.

| District | Elevation (m) | 2018/2019 | 2019/2020 | 2020/2021 | 2021/2022 | 2022/2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kathmandu valleya | 1250–1310 | — | 27 | 46 | 64 | 169 |

| Kaski | 700–800 | 500 | 612 | 579 | 457 | 1304 |

| Kavrepalanchowk | 1450 | 35 | 12 | 8 | 6 | 0 |

| Chitwan | 200–210 | — | 34 | 202 | 453 | 161 |

| Nawalparasi East | 110–120 | — | — | — | — | 11 |

| Parsa | 236 | — | — | — | — | 1 |

| Sarlahi | 101 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 |

| Sunsari | 70–105 | 0 | 4 | 26 | 335 | 211 |

| Dhanusa | 125 | — | — | — | — | 6 |

| Saptari | 62 | — | — | — | — | 1 |

| Udayapur | 70 | — | — | — | — | 180 |

| Jhapa | 110–150 | — | — | 7 | 12 | 13 |

| Kailali | 112 | — | — | — | 152 | 12 |

| Kanchanpur | 200 | — | — | — | — | 1 |

| Total count | 535 | 689 | 868 | 1479 | 2120 |

- a Kathmandu valley includes three districts—Kathmandu, Bhaktapur, and Lalitpur—and Yellow-breasted buntings have been recorded in all these districts. A value of “0” indicates that the area was surveyed, but the species was not recorded during the survey, whereas “—” indicates that no survey was conducted during the specified time period focusing on the species.

3.2 Fine-Scale Habitat Characterization

We measured the fine-scale habitat use of the Yellow-breasted Bunting in 57 plots during the 2022–2023 period. The mean distance between the plots and the nearest settlement was 759.82 ± 209.51 m, and to the nearest wetland, it was 186.28 ± 39.15 m. Most plots were within or very close to agricultural land (mean 303.68 ± 186.03 m), except for one plot in Parsa National Park, which was approximately 9.92 km away.

The fine-scale habitat data showed that the Yellow-breasted Bunting predominantly utilized agricultural land (79%), followed by grassland patches (14%), with minimal presence in reeds or grass species within wetland habitats (Table 2). These habitats were predominantly dry (67%), followed by wet (17%), and waterlogged (16%) (Table 2). We observed signs of grazing in 35% of the plots, vegetation clearance in 46%, and fire presence in only 11% of the plots (Table 2). We recorded the presence of a few trees in 23% of the plots.

| Parameters category | No. of plots | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Habitat | Agricultural land | 45 | 79 |

| Wetland | 4 | 7 | |

| Grassland | 8 | 14 | |

| Soil moisture/habitat condition | Wet | 10 | 17 |

| Waterlogged | 9 | 16 | |

| Dry | 38 | 67 | |

| Grazing | Yes | 20 | 35 |

| No | 37 | 65 | |

| Fire | Yes | 6 | 11 |

| No | 51 | 89 | |

| Vegetation clearance | Yes | 26 | 46 |

| No | 31 | 54 | |

| Mean | Standard error | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Shrub | Cover (%) | 4.78 | 1.82 |

| Height (cm) | 36.49 | 9.68 | |

| Grass | Cover (%) | 31.22 | 5.42 |

| Height (cm) | 72.24 | 16.56 | |

| Crop | Cover (%) | 48.50 | 5.98 |

| Height (cm) | 82.19 | 12.72 |

The mean crop cover was the highest, followed by grass and shrub cover, while the mean grass height was the tallest, followed by crop and shrub height (Table 2). Different shrubs, such as Ipomoea carnea and Ageratina adenophora, were present in smaller proportions. The Yellow-breasted Buntings feed in various types of agricultural lands, including rice (Oryza sativa), mustard (Brassica nigra), wheat (Triticum aestivum), and fallow fields (recently harvested rice/wheat, small grasses like Cynodon dactylon, and plowed fields). They roost primarily in agricultural lands with tall sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum; unharvested during the time), maize (Zea mays), or grasses such as Saccharum spontaneum and Phragmites karka found in grassland and wetland habitats.

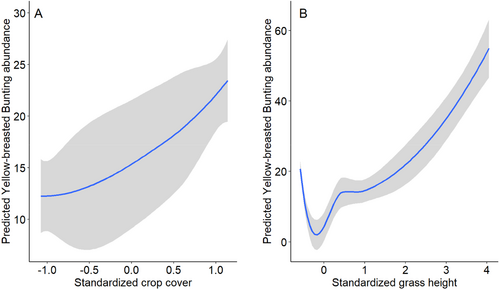

3.3 Factors Affecting the Abundance of the Yellow-Breasted Bunting

The model identified the combination of crop cover and grass height as the best predictor of Yellow-breasted Bunting abundance in our study area (ΔAICc = 0; Table 3). An alternative model that included shrub cover, crop cover, and grass height described the data equally well (ΔAICc < 2; Table 3). However, only crop cover and grass height showed a significant impact, with Yellow-breasted Bunting abundance increasing notably as crop cover and grass height increased (Figure 2A,B).

| Parameters | df | Log-likelihood | AICc | ΔAICc | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crop cover + Grass height | 5 | −236.38 | 484.0 | 0 | 0.31 |

| Crop cover + Grass height + Shrub cover | 6 | −235.23 | 484.2 | 0.2 | 0.28 |

| Crop cover + Grass height + Crop height | 6 | −236.16 | 486.0 | 2.06 | 0.11 |

| Crop cover + Grass height + Crop height + Shrub cover | 7 | −235.00 | 486.3 | 2.33 | 0.09 |

| Crop cover + Grass height + Grass cover | 6 | −236.38 | 486.5 | 2.5 | 0.09 |

- Abbreviations: AICc, corrected Akaike Information Criterion; ΔAICc, difference in AICc from the best model; df, degrees of freedom—number of estimated parameters in the model; Weight, Akaike model weight.

4 Discussion

We recorded the presence of Yellow-breasted Buntings mostly in the mid-hills and lowland regions of Nepal, spanning from east to far west, and notably outside protected areas. They predominantly utilize agricultural landscapes, with their habitat use being positively influenced by crop cover and grass height.

Over the past 8 years, we documented the presence of the Yellow-breasted Bunting in 22 districts, encompassing the majority of their historic records in Nepal (Inskipp et al. 2016). Our study contributes additional sightings from central and eastern Nepal, underscoring the importance of these landscapes as habitats for the species. Previously, there had been no systematic population count of the species. Although we recorded a 43% increase in the population of the Yellow-breasted Bunting in 2022–2023 compared to the previous year, this is possibly attributed to increased efforts, both in terms of personnel and the coverage of more sites. However, opportunistic sightings indicated a maximum of around 7000 individuals in the Koshi area during the 1980s (Inskipp et al. 2016), showing a rapid population decline of around 70% compared to the current population count throughout Nepal. After this dramatic population decrease, most of the flocks were below 500 individuals, except for one observed in the Lumbini area, consisting of approximately 2000 individuals in 2006 (Inskipp et al. 2016). Such a decline is possibly due to excessive Bagedi (Nepali name for buntings, which also includes other similar-sized farmland birds) trapping and eating practices occurring in the lowlands of Nepal (Katuwal et al. 2023), and along their migratory routes (Kamp et al. 2015). This is not unique to Nepal; there are also fewer flocks and fewer studies addressing the distribution and population across other South Asian countries where the species winters (BirdLife International 2017; Saika and Choudhury 2023; SoIB 2023). For example, due to insufficient data, trend analysis in India remains difficult (SoIB 2023). However, a recent study from Thailand and Cambodia recorded around 10,000 and 2,900 Yellow-breasted Buntings in their wintering grounds, respectively (Ly et al. 2022; Simla 2024), indicating that a significant number of them utilize Southeast Asian countries for wintering. As Nepal usually lies outside the suitable predicted habitats for the species (Heim et al. 2020)—likely due to the lack of data input from the country, as well as some climatic and geographical differences compared to Southeast Asian countries—this pattern requires further comparative study to be fully understood. Therefore, our study provides essential distribution and population count data from Nepal's wintering grounds, which can help update the status of the species for global communities.

Most Yellow-breasted Bunting presence sites in our study were located near agricultural land, wetlands, and settlements, likely reflecting their adaptation to or preference for human-dominated landscapes. Additionally, their high occurrences in agricultural habitats, both for foraging and roosting, may be due to lower levels of mechanization, reduced intensification, and higher habitat heterogeneity, which contrasts with studies from Europe and North America, where agricultural land is considered detrimental to birds due to high intensification (Rigal et al. 2023; Stanton et al. 2018). Not only at a fine-scale level but also at a large scale, most of these habitats are primarily agricultural lands, highlighting the Yellow-breasted Bunting's dependence on and adaptability to human-modified landscapes. Notably, sugarcane fields emerge as the most utilized habitat due to their provision of both foraging and roosting opportunities, as reported for other bird species (Lukhele et al. 2021). Although mist-netting for crop protection is not commonly observed in Nepal—a practice often considered an ecological trap, as seen in Southeast Asian countries (Angkaew et al. 2022)—it is important to note that sugarcane fields are frequently used by hunters for trapping these birds (Katuwal et al. 2023), underscoring the need for regular monitoring. Conversely, a study in Thailand highlights rice fields being more frequently used by the species, further underscoring agricultural lands as critical wintering habitats in Southeast Asia (Simla 2024). In addition to agricultural land, grasslands—whether in riverine or other wetland habitats—also constitute a significant habitat (Beermann et al. 2021; BirdLife International 2017; Inskipp et al. 2016; Saika and Choudhury 2023). It should also be noted that these grassland habitats are either within or very close to agricultural areas, indicating the paramount importance of agricultural landscapes as habitats, both for feeding and roosting. In most habitats, soil moisture levels were drier, likely because agricultural lands were fallow or less irrigated during the winter season, creating suitable foraging conditions for the species. Similarly, vegetation clearance and grazing within the plots might help Yellow-breasted Buntings find food, while trees offer roosting sites, highlighting their adaptability to human-used agricultural areas. Nevertheless, we recommend in-depth studies to better understand how such anthropogenic activities influence their behavior and occurrences.

Our findings show that crop cover and grass height are the best predictors of Yellow-breasted Bunting abundance. Crop cover provides a better habitat for the Yellow-breasted Bunting for activities like foraging, concealing, and roosting, so increasing its cover is beneficial for this species, as well as other farmland species (Katuwal et al. 2022). However, it is important to note that these crops, particularly due to their dense cover and height, can also restrict sightings of the species (e.g., sugarcane; Butler and Gillings 2004). The model in our study also indicated the positive influence of grass height on Yellow-breasted Bunting abundance, as birds likely benefit from taller grasses that provide concealment and roosting advantages. We recommend thoroughly searching tall grasslands, particularly those inside Chitwan National Park and Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve, as we occasionally observed the birds flying into these habitats. However, the practices of burning and collecting grasses, both inside and outside protected areas, pose challenges for the species. Leaving patches of grassland unburned or uncut can provide important habitats for Yellow-breasted Buntings. Similar use of tall grasses by these buntings has also been observed in their other wintering grounds (Ly et al. 2022; Saika and Choudhury 2023). Furthermore, in another competing model (shrub cover, crop cover, and grass height: ΔAICc < 2), shrub cover did not show statistical significance for the species, possibly due to the minimal presence of shrubs in agricultural lands; however, further studies are needed, as buntings have been observed using shrubs for roosting and feeding (HBK personal observations). Overall, our study underscores the need for effective agricultural land management. For instance, leaving some sugarcane and rice field patches unharvested, promoting maize cultivation, and maintaining a few grassland patches within agricultural areas that consistently meet the cover and height requirements for buntings during the wintering period.

There are several potential limitations to our study that need to be addressed. The Yellow-breasted Bunting is a rare species with very low sighting rates, and some individuals are passage migrants, which makes systematic surveys challenging. As some populations are passage migrants, mismatches in population counts cannot be completely ruled out, even though we attempted to monitor different sites at the same time as far as possible. Consequently, we established fewer plots during the study period and were unable to monitor the population or habitat use multiple times per month, which may have reduced the sample size for our analysis. Additionally, we were unable to thoroughly survey their population across the grasslands within the core areas of the protected areas. Nevertheless, we believe our study can provide useful baseline data for future research. Regular monitoring across larger plot sizes could offer more detailed insights into their population and habitat use, information essential for a landscape-scale conservation approach.

5 Conclusions and Conservation Recommendations

Our study shows that agricultural lands provide important foraging and roosting habitats for the Yellow-breasted Bunting in Nepal. Although the number of sightings and the population of Yellow-breasted Buntings have increased in recent years, the current population remains significantly lower than in the 1980s. The combination of crop cover and grass height was identified as the best model for predicting Yellow-breasted Bunting abundance, showing a positive influence on their numbers. These findings suggest that Nepal's agricultural lands can provide crucial habitats for this globally threatened species. However, effective habitat management that optimizes crop cover and grass height is key for supporting the Yellow-breasted Bunting population.

We recommend managing sugarcane harvests to preserve patches of habitat suitable for roosting and foraging. Furthermore, planting maize could enhance support for these populations. Thorough surveys across grassland habitats, particularly in Chitwan National Park and Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve, are paramount. Additionally, when burning grasslands in winter, leaving some patches untouched can provide essential habitats for Yellow-breasted Buntings. Since the recorded locations of the species are predominantly outside protected areas and in agricultural lands, it is crucial to launch participatory conservation campaigns to raise awareness among local farmers about safeguarding both the species and its habitat. This includes controlling trapping and trading activities, as well as reducing pesticide use. Continuous monitoring of population dynamics and habitat use patterns in wintering habitats is imperative to ensure the conservation of this species.

Author Contributions

Hem Bahadur Katuwal: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Krishna Prasad Bhusal: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, resources, visualization, writing – review and editing. Ankit Bilash Joshi: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, visualization, writing – review and editing. Deu Bahadur Rana: investigation, data curation, visualization, writing – review and editing. Mohan Bikram Shrestha: Investigation, data curation, writing – review and editing. Prashant Rokka: investigation, data curation, writing – review and editing. Rui-Chang Quan: conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, visualization, writing – review and editing.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Yunnan Province Science and Technology Department (202203AP140007), CAS-SEABRI (Y4ZK111B01), International Science, and Technology Commissioner of Yunnan Province (202203AK140027), Yunnan Revitalization Talent Support Program “Innovation Team” Project (202405AS350019), Hong Kong Bird Watching Society- Asia Conservation Fund, Bird Conservation Nepal and Japan Bird Research Association. We would like to thank the Department of Forests and Soil Conservation and the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation for providing permission to carry out this study. We would also like to thank Ishwari Chaudhary, Santosh Bajagain, Milan Baral, Yam Mahato, Ganesh Sah, Hirulal Dangaura, Anish Timsina, Deven Kharel, Yubin Raj Shrestha, Carol Inskipp, Sandeep Regmi, Ramesh Chaudhary, Simba Chan, and all people who directly or indirectly provided crucial information, support and suggestions during the study. We would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and feedback, which greatly improved the manuscript.

Ethics Statements

This study does not involve handling any species and therefore does not require ethical clearance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of Interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data will be available from the corresponding author upon request.