Towards zero extinction—A case study focusing on the plant genus Begonia in Thailand

实现“零灭绝”——聚焦泰国秋海棠属植物的一个案例

Editor-in-Chief & Handling Editor: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz

Abstract

enPlant species with small habitat ranges and specific edaphic requirements are highly vulnerable to extinction and thus require enhanced attention in biodiversity conservation. This study was designed to explore the challenges of protecting such plant species by evaluating the in situ and ex situ conservation capacities available for Thailand's species of the mega-diverse plant genus Begonia L. A comprehensive assessment of occurrence records across the country was conducted to evaluate the spatial distribution of Begonia diversity in Thailand, identify biodiversity hotspots, assess the extinction threats faced by the 60 Begonia species known in the country, and identify existing conservation capacities and potential gaps. The results show that 78% of Begonia species in Thailand are vulnerable to extinction, with the Northern floristic region identified as both a Begonia species hotspot and a region with major conservation gaps. While in situ conservation efforts have been successful in covering over 88% of the species, they have failed to provide the protection required to achieve zero extinction. Ex situ conservation capacities are poorly developed, with only 13% of species present in botanical gardens, and no seed banking or other related activities have been initiated. This evaluation presents a sharply contrasting message: on one hand, Thailand has assembled substantial capacities to protect these plants through established national parks and other protected areas, but on the other hand, essential capacities are still lacking to render the zero extinction target achievable. We advocate for the implementation of a multi-component conservation strategy to enable Thailand to move towards zero species extinction, even for plant species with narrow habitat ranges and high edaphic specialisation.

摘要

zh栖息地范围小且环境特异性高的植物物种面临极高的灭绝风险,因此需要在生物多样性保护方面给予更多关注。本研究的目的是通过评估就地和异地保护的能力,明确保护此类植物物种所面临的挑战,以保护泰国多样性极高的秋海棠属物种。为此,研究人员对泰国全国范围内的秋海棠物种出现记录进行了综合评估,以了解泰国秋海棠多样性的空间分布,确定生物多样性热点地区以及60个面临灭绝威胁的物种,并最终确定现有保护能力和保护的不足。结果表明,泰国78%的秋海棠物种濒临灭绝,而北部花卉区不仅是秋海棠物种的热点地区,也是主要的保护空白区。就地保护工作成功覆盖了88%以上的物种,但未能提供实现零灭绝所需的保护。异地保护能力很差,只有13%的秋海棠物种在植物园中展示,种子库及相关行动都尚未开展。本评估报告提供了一种“表里不一”的信息。一方面,泰国已经建立了国家公园和其他保护区,具备了保护这些植物的强大能力。另一方面,泰国仍然缺乏实现物种零灭绝目标的能力。在此,我们提倡实施多重保护的策略,进一步促使泰国实现物种零灭绝,即使是栖息地范围窄、环境特异性高的植物物种也不例外。【审阅:周聪】

Plain language summary

enEvaluating the extinction risk faced by rare plant species due to human activities is a pressing issue for improving our ability to meet zero extinction targets. Most species within the mega-diverse plant genus Begonia are particularly vulnerable due to their rarity, which is a result of their high ecological specialisation. While existing natural parks and other protection areas offer refuge for many species—covering nearly 90% of the Begonia species diversity in Thailand—additional conservation measures are required to achieve the goal of zero extinction. These measures may include the establishment of new micro-protection sites or the development of ex situ conservation protocols. As a consequence, effective biodiversity conservation aimed at zero extinction cannot rely solely on the design of large-scale protected areas but must also include highly targeted actions focused on rare species facing significant extinction threats. In short, the conservation of rare plant species is best approached by implementing a multi-component conservation strategy, which is key to ensuring the long-term viability of these species and moving closer to the goal of zero species extinction.

简明摘要

zh评估稀有植物物种因人类活动而面临的灭绝风险,是提高我们实现“零灭绝”目标的一个紧迫问题。秋海棠属植物种类繁多,由于其高度生态特异性造成的稀有性,大多数物种都特别脆弱。现有的自然公园和其他保护区为许多物种提供了庇护,例如在泰国,近 90% 的海棠物种多样性都得到了保护。然而,要实现“零灭绝”目标,还需要采取更多的保护措施,无论是以新的微型保护区的形式,还是以异地保护协议的形式。因此,要有效保护生物多样性,实现零灭绝,不能仅仅依靠设计大规模Title的保护区,还要采取高度针对性的行动,重点保护面临高度灭绝威胁的稀有物种。简而言之,保护珍稀植物物种的最佳途径是实施多重保护战略,以此实现物种零灭绝的目标,确保这些植物物种的长期生存能力。

Practitioner points

en

-

Assess species vulnerability by utilising occurrence data from fieldwork and online historical records to reliably evaluate key criteria such as area of occupancy, endemism, number of recorded locations, and the proportion of these locations within protected areas.

-

Establish evidence-based conservation priorities to address gaps in conservation capacities, such as unprotected diversity hotspots and species not currently growing in protected areas.

-

Develop and implement strategies to expand conservation capacities for priority species through targeted ex situ and in situ conservation interventions.

实践者要点

zh

-

利用实地考察获得的物种出现数据和在线资源提供的历史记录,可评估物种濒临灭绝的脆弱性,这些数据和记录可用于对一些标准进行可靠评估,如地区占有率、特有性、记录的位点数和保护区内位点比例。

-

确定以证据为基础的优先事项,以解决保护能力方面的不足,如未受保护的多样性热点地区和未在保护区生长的物种。

-

确定扩大保护能力的策略,通过采取有针对性的就地和异地保护干预措施,保护在优先名单上的物种。

1 INTRODUCTION

Stopping the sixth mass extinction, primarily caused by anthropogenic degradation and transformation of ecosystems, has been recognised as one of the critical challenges for securing the future development, health and prosperity of humanity (Ceballos et al., 2015; Di Marco et al., 2018; Hughes, 2023; Pimm & Raven, 2017). Significant emphasis has been placed on area-based conservation strategies, particularly through the establishment of protected areas such as national parks and forest reserves, which are essential for protecting species, communities, and ecosystems (Maxwell et al., 2020). Protected areas are undeniably a key component in achieving the four primary goals and 23 targets of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (K-M GBF; CBD, 2022), such as the preservation of ecosystem diversity by effective mitigation of human-induced species extinction. The importance of protected areas is reflected by the ‘30 by 30’ target, which aims to safeguard 30% of the planet's surface by 2030 (Hughes & Grumbine, 2023; Watson et al., 2023). Some even consider these targets as surrogates for the broader goal of zero species extinction, though current assessments indicate that fully achieving this objective remains out of reach. Improved monitoring of the extinction threats to vulnerable plants is crucial, but it is often challenging to pinpoint necessary actions and evaluate the effectiveness of implemented conservation efforts (Corlett, 2023; Luther et al., 2021; Parr et al., 2009; Ricketts et al., 2005). Addressing these challenges is critical to making progress towards the zero extinction target, which requires overcoming the existing shortfalls in documenting and reviewing conservation interventions (Senior et al., 2024). Here, we propose that major progress can be made by carrying out focused assessments of selected lineages within specific regions or nations. These assessments should integrate: (1) documentation of the vulnerability of studied species to extinction threats and (2) evaluation of existing conservation capacities, along with identification of gaps in current consideration interventions. Special attention should be given to both in situ conservation capacities, such as protected areas, and ex situ conservation actions supported by facilities such as botanical gardens and seed banks, which are essential for maintaining living collections and genetic material (Chapman et al., 2019; Edwards & Jackson, 2019; Heywood, 2011; Ren & Antonelli, 2023; Walters & Pence, 2021).

To explore the feasibility of the proposed inventories of conservation needs and actions, this study focused on the 60 species of the flowering plant genus Begonia L. occurring in Thailand. With approximately 2144 species, the genus Begonia is one of the mega-diverse plant genera (Moonlight et al., 2024), comprising many species with narrow distribution ranges and often highly specialised environmental preferences, for example, exposed limestone outcrops (Phutthai et al., 2009). Southeast Asia is recognised as a center of species diversity for this genus, which has been identified as a flagship taxon in efforts to conserve not only species endemic to karst environments but also the ecosystem functions of these unique habitats (Kiew, 2001). Begonia species are highly valued as ornamental plants, making them susceptible to habitat loss as well as pressures from legal and illegal horticultural trade (Tian et al., 2018). The often limited ranges and frequent exclusive occurrences in highly fragmented habitats increase the vulnerability of these plants to the impacts of global climate change (Corlett & Tomlinson, 2020; Ma et al., 2013; Pomoim, Hughes, et al., 2022; Pomoim, Trisurat, et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2018). In summary, the majority of Begonia species are likely to be vulnerable to extinction threats, and the survival of many species may hinge on conservation interventions that protect species integrity by focusing on the conservation of their genetic diversity (Allendorf et al., 2010; Li et al., 2018; Xiao et al., 2023).

Thailand is of particular interest in the context of the ‘30 by 30’ target due to the nation's significant efforts to establish in situ conservation through protected areas, which currently cover more than 20% of the country's land area (Singh et al., 2021; Pomoim, Hughes, et al., 2002; Pomoim, Trisurat, et al., 2022). This coverage includes contributions from national parks (~12.4% of the land area), wildlife sanctuaries (~7.3% of the land area), nonhunting areas (~1.2 of the land area) and forest reserves (~02. of the land area). Evidence-based inferences of the effectiveness of the existing protected areas have been published with the aim of guiding their expansion, but these studies have predominantly focused on birds and mammals (Pomoim et al., 2021; Pomoim, Hughes, et al., 2022; Pomoim, Trisurat, et al., 2022; Singh et al., 2021). Overcoming the issue of 'plant blindness', which refers to the underrepresentation of plant awareness in biodiversity conservation efforts, is essential for developing successful conservation strategies that protect species and also ecosystem functionality (Balding & Williams, 2016; Corlett, 2023; Dünser et al., 2024).

The study aims to overcome the challenge of assessing extinction vulnerability by employing several readily obtainable criteria, as opposed to the more time-consuming full IUCN Red List standard assessments (IUCN, 2024). Until now, only 96 species of Begonia worldwide (<5%) are formally listed in the IUCN Threatened Plant list, with none known to occur in Thailand. World Flora Online (2024; https://www.worldfloraonline.org) recorded six out of 16 species with assents as threatened (15.9%), while additional resources enhanced the number of varying levels of threat assessments available for 44 species (Chamchumroon et al., 2017; Phutthai et al., 2019). According to these data, about 77% of Begonia species occurring in Thailand are vulnerable. To increase the number of species evaluated, the study consistently applied the restricted area criterion (=criteria 2A and 2B of the ICUN Criteria) and considered other factors such as endemism, the number of localities recorded and the proportion of localities within protected areas. These four variables were used to evaluate the capacity for in situ conservation via protected areas, excluding replantation efforts. The potential for ex situ conservation through botanical gardens was also explored (BGO, 2020).

Furthermore, this study aims to evaluate the spatial distribution of Begonia species diversity in Thailand, not only to identify biodiversity hotspots but also to establish a framework for evaluating existing conservation capacities with the goal of achieving zero species extinction for the Begonia genus in Thailand. To do so, the study assembled the most comprehensive data set of Begonia occurrence records in Thailand, carried out spatial biodiversity analyses, assessed the extinct threat status of each species using IUCN Criterion B, determined the occurrence within and outside protected areas, and finally identified the number of species currently cultivated in the country's botanical gardens. These analyses were designed to address the following research objectives: (1) evaluate the effectiveness of existing protection capacities in Thailand to achieve the zero Begonia species extinction target, focusing on in situ conservation (e.g. national parks) and ex situ conservation (e.g. botanical gardens); (2) identify gaps in current conservation capacities that must be addressed to protect all Begonia species, with emphasis on the establishment of a priority list of species in need of protection; and (3) investigate the status of ex situ conservation capacities and promote their utilisation to protect the genetic diversity and health of Begonia species.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Assessing the Begonia diversity occurring in Thailand

In support of the aims of this study, it is important to note that the taxonomy of Thailand's Begonia species is well-established (Peng et al., 2017; Phutthai & Hughes, 2016; Phutthai & Hughes, 2017a; 2017b; Phutthai et al., 2012, 2014, 2019, 2021; Phutthai & Sridith, 2010; Radbouchoom et al., 2023). Thus, the study does not need to address taxonomic ambiguities that could otherwise limit the reliability of results regarding the spatial distribution of species diversity and the assessment of extinction threats.

In total, 2484 occurrence records of Begonia species in Thailand were obtained via the integration of several data collection strategies. First, a series of field surveys were conducted across Thailand with the aim of expanding records of these plants' distribution and ecological preferences, with a particular focus on occurrences outside protected areas. These field surveys, conducted between 2020 and 2021, covered multiple provinces, including Chiang Mai, Chumporn, Kanchanaburi, Lampang, Ratchaburi, Ranong, Tak, Trang and Krabi. Second, occurrence data were assembled by studying voucher specimens deposited in two key herbaria in Thailand: the Forest Herbarium in Bangkok (BKF) and the Queen Sirikit Botanic Garden Herbarium in Chiang Mai (QBG). In addition, information was obtained by studying voucher specimens outside Thailand, specifically AAU, ABD, BM, BK, E, K, HAST, LUN, L, P, PE, QUB, and SING. The abbreviations used follow the Herbarium Codes as given in the Index Herbariorum (Thiers, 2024). Specimen searches utilised databases accessible via institutional websites, the Begonia Resource Center (https://padme.rbge.org.uk/Begonia/home; Hughes et al., 2015), and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF; https://www.gbif.org). Finally, publications on the flora of Thailand were studied to extract further distribution data (Phutthai et al., 2012, 2014, 2019, 2021; Phutthai & Sridith, 2010). The species taxonomy followed recent treatments (Moonlight et al., 2018). The taxonomic accuracy of all accessions was carefully verified by the two taxon experts on the author team (TP and SR) accessions to ensure the data's integrity. The final data set was cleaned by removing occurrences based on accessions with ambiguous species identification, incorrect coordinates or erroneous placement within Thailand. Wherever possible, spatial coordinates were assigned to accessions that had not been previously geo-referenced. Voucher collections lacking sufficient information about the collection site were excluded. All maps used in this study were handled using QGIS.org (2021).

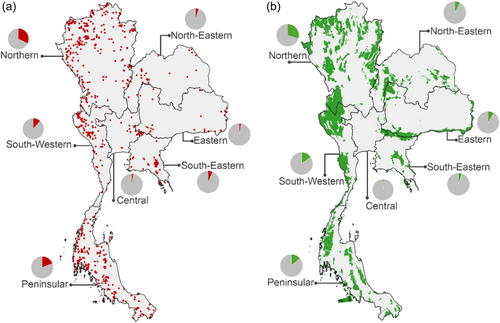

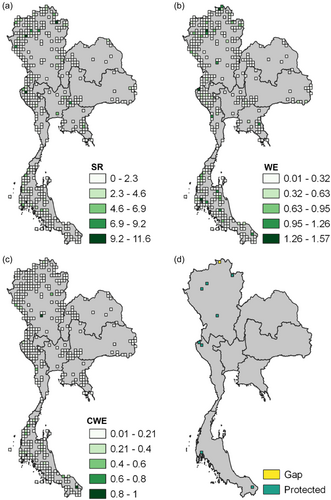

2.2 Evaluation of the spatial distribution and identification of hotspots

The assembled occurrence records for all 60 species of Begonia known to occur in Thailand were used to reconstruct the spatial distribution of this diversity across the country. Specific attention was given to the seven floristic regions: Northern, North-Eastern, Eastern, Central, South-Eastern and Peninsular (Phutthai et al., 2009; Trisurat et al., 2011). The software Biodiverse 4.0 was used to estimate three widely applied biodiversity indices: Species Richness (SR), Weighted Endemism (WE), and Corrected Weighted Endemism (CWE) (Laffan et al., 2010). These values were estimated utilising a 0.25-degree grid cell map of Thailand. By considering both the spatial distribution of species richness and weighted endemism across all grids, hotspots of Begonia diversity in Thailand were localised.

2.3 Assessment of the extinction threats experienced by Thailand's Begonia species based on their restricted geographic range (=criterion B)

The vulnerability of each Begonia species to extinction threats was evaluated by applying the IUCN Criteria B1 & B2, implemented through the ‘ConR’ package in R version 4.3.0 (Dauby, 2017; R Core Team, 2023). Given that for most species, only distributional data is available, the application of the restricted area criterion (see IUCN, 2017–2020) was deemed most appropriate. Future studies will hopefully also provide estimates of population size for each species, which would allow for the consideration of Criteria C and D as well. In this study, the available data was restricted to recorded occurrences, allowing the application of Criterion B1, which focuses on the extent of occurrence (EOO), and Criterion B2, which explores the area of occupancy (AOO) based on currently occupied suitable habitats. The analysis was conducted using a 0.25-degree grid cell resolution. Species with fewer than three occurrence records were classified as Data Deficient (DD). For species with more than three occurrences, their threat status was determined by comparing the estimated EOO value and AOO values: Critically Endangered (CR) taxa had an EOO of less than 100 km2 and AOO of less than 10 km2, Endangered (EN) taxa had an EOO of less than 5000 km2 and AOO of less than 500 km2, Vulnerable (VU) taxa had an EOO of less than 20,000 km2 and AOO of less than 2000 km2, and Near Threatened (NT) or Least Concern (LC) taxa had an EOO of more than 20,000 km2 and AOO of more than 2000 km2 (see IUCN, 2017–2020). In cases where EOO values were lower than AOO values, both values were treated equally. The analyses generated maps visualised in 0.25-degree grid cells, representing the number of recorded species and the proportion of threatened species within each cell.

2.4 Inferring conservation capacities

Based on the location within or outside protected areas, species occurrences were categorised as either in situ protected or not. This categorisation was achieved by overlaying species distribution maps with the map of protected areas in Thailand. The protected areas included in the analysis were those fitting the IUCN Category 1a (Strict Nature Reserve) and IUCN Category II (National Park), as provided by the Department of Natural Resources and Wildlife of Thailand. This assembled map specified the distribution of 268 protected areas suitable for in situ conservation of Begonia, namely national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, and nonhunting areas. Specific attention was given to species whose entire range occurs outside protected areas, as these species are likely more vulnerable and in need of conservation efforts. The assessment also aimed to identify gaps in conservation coverage by identifying hotspots that fall outside of protected areas. To evaluate ex situ conservation capacities, we identified the number of Begonia species currently cultivated in botanical gardens, with special attention paid to the Queen Sirikit Botanic Garden. Furthermore, we searched for evidence suggesting the existence of specific ex situ programmes, such as targeted reproduction of Begonia species in botanical gardens followed by replanting in the wild or the establishment of resources aiming to preserve the genetic diversity of these plants, such as seed banks.

3 RESULTS

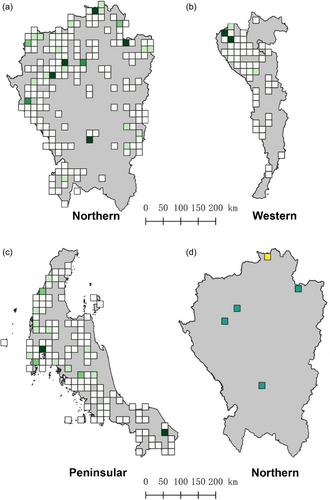

3.1 Spatial distribution of the 60 species of Begonia in Thailand

Although Begonia species are reported from various parts of Thailand, the majority of occurrence records are concentrated in three floristic regions (Figure 1; Supporting Information: File S1). The Northern floristic region is particularly notable, contributing 46% of the total occurrences in Thailand. The Peninsula floristic region follows, accounting for 26%, while the Southwestern floristic region contributes 12%. This uneven distribution is reflected in the diversity indices applied, which reveal disparities in species richness, weighted endemism and corrected weighted endemism (Figures 2 and 3). Consequently, several hotspots were detected: five in the Northern floristic region, two in the Peninsula floristic region, and two in the Southwestern floristic region (Figure 2d). Of these nine hotspots, only one is located outside a protected area, specifically in Chiang Rai province (Figures 2d and 3d). This gap in the protection of diversity hotspots was found to be located in the most northern parts of the Northern floristic region.

3.2 Inference of the vulnerability to extinction threats considering the restricted geographic range

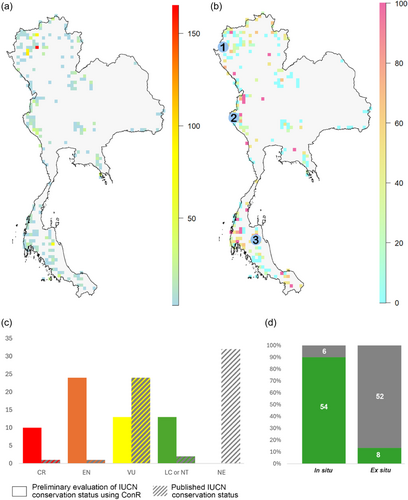

The vast majority of the 60 species are known from only one or a few locations, indicating their vulnerability due to restricted geographic range. The most notable exceptions were widespread species such as B. integrifolia Dalzell (71 locations), B. palmata D.Don (30 locations), and B. sinuata Wall. ex Meisn. (30 locations). Among the 26 taxa endemic to Thailand, seven taxa were recorded from a single location, five taxa from two locations, two taxa from three locations, and three taxa from four locations. The remaining endemic species were distributed across five to six locations. The extinction threat assessment covered all 60 species, focusing solely on their occurrences within Thailand (Figure 4; Supporting Information: File S2). Using the ‘ConR’ package and applying the IUCN Category B2a, 31 species were classified under this criterion, while 28 species were classified under B1a+B2a, and one species under B1a. According to the AOO criterion, 13 species were evaluated as Least Concern or Nearly Threatened. The remaining species were inferred to be threatened, with 10 species as Critically Endangered, 24 species as Endangered, and 13 species as Vulnerable. The EOO criterion could not be applied to 10 species. For the remaining species, 27 were evaluated as non-threatened, while the rest were categorised as threatened, with three species as Critically Endangered, 10 species as Endangered, and 10 species as Vulnerable (Figure 4).

3.3 Capacity to protect Begonia diversity in Thailand

Approximately 63% of all recorded Begonia occurrences were located in protected areas, although these areas only cover 23% of Thailand's land area. 53 species (88.3%) had at least some occurrence within protected areas, whereas seven species (11.7%) were exclusively found outside these areas (Figure 4; Supporting Information: File S2). The effectiveness of in situ conservation provided by protected areas varied among species. Some widespread species had a relatively small proportion of their known locations within protected areas, whereas certain rare species were entirely confined to these protected zones. Despite the high ornamental value of Begonia species, only eight species were recorded as being cultivated in botanical gardens, with most located at the Queen Sirikit Botanic Garden (QBG) (Figure 4d). The species found at QBG showcased promising ornamental properties, making them suitable for exhibition purposes. Additionally, QBG also harboured several rare and endangered species, which were observed to thrive under controlled conditions (BGO, 2020). In total, 11 species were known from only a single location, of which seven species were found to be endemic to Thailand (B. exposita Phutthai & M. Hughes, B. festiva Craib, B. khaophanomensis Phutthai & M. Hughes, B. pengchingii Phutthai & M. Hughes, B. sirindhorniana Phutthai, Thananth., Srisom & Suddee, B. smithiae E.T. Geddes, B. subviridis Craib). The remaining four species were also found in neighbouring countries to the south (B. barbellata Ridl, B. kingiana Irmsch.) or northern neighbour nations (B. hymenophylla Gagnep., B. surculigera Kurz). All eleven of these species were evaluated as Critically Endangered or Endangered based on the AOO category. Four of these species—B. exposita, B. pengchingii, B. sirindhorniana, and B. surculigera Kurz—were among the seven species with no known locations within protected areas. The other three species—B. bella Phutthai, B. fulgurata C.I Peng, C.W. Lin & Phutthai, and B. silletensis (A. DC.) C.B. Clarke—were known from two or three locations, with the first two being endemic to Thailand. Besides the seven species known from a single location occurring in protected areas, three species—B. incondita Craib, B. sandalifolia C.B. Clarke and B. tenasserimensis Phutthai & M. Hughes—known from two locations, both in protected areas. Conversely, some species with more than 10 known locations had only a small proportion of these within protected areas. For example, B. integrifolia Dalzell had only 4.2% of its known locations in protected areas. Similarly, some endemic species with more than five known locations had 50% or fewer occurrences within protected areas, such as B. saxifragifolia Craib, with only 18.2% of its locations in protected areas (Supporting Information: File S2).

4 DISCUSSION

This study has successfully identified the priorities required to implement conservation inventions aimed at protecting all Begonia species occurring in Thailand. This outcome was achieved by analysing distribution records to explore the spatial distribution of Begonia species within the country, assessing their vulnerability to extinction threats using the restricted area criterion, and identifying gaps in existing and newly proposed conservation capacities. The findings of this study provide a potential blueprint for evaluating the effectiveness of current conservation practices in achieving zero species extinction across all lineages of land plants. Specifically, the study relied on early-obtained data, such as occurrence data, to perform these evaluations. The results have provided a framework for establishing priority species lists, which can guide the expansion of conservation capacities through the species-specific implementation of ex situ and/or in situ conservation strategies. However, it is important to acknowledge that this rather simplistic approach comes with certain strengths and weaknesses related to the data obtained.

4.1 Taxonomy challenge

Determining the number of species that need protection against extinction threats is significantly challenged by the lack of adequate taxonomic research, which is key for effective conservation (Sandall et al., 2023; Thomson et al., 2018). Unfortunately, taxonomic expertise is often poorly established and maintained for many plant lineages (Löbl et al., 2023). This is regrettable because advancements in taxonomic research are essential to enable progress towards the zero extinction target. These advancements are required not only to discover and describe the many species that remain unidentified but also to correct errors in existing taxonomic classifications as new biological insights are gained. Such research may lead to the redefinition of previously described species, either by recognising over-looked species or by synonymising unnatural taxonomic units. To support access to taxonomic expertise, new digital infrastructures are being developed to facilitate rapid access to and exchange of information on all plant species (Sandall et al., 2023). Notable examples include the Plants of the World Online (POWO, 2024) by the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew (https://powo.science.kew.org) and World Flora Online (https://www.worldfloraonline.org). This study benefited from ongoing efforts to clarify the taxonomy of Begonia both in Thailand and globally. These efforts have provided a robust framework for species recognition and access to valuable metadata of the taxa through resources like the Begonia Resource Center (https://padme.rbge.org.uk/begonia/) and the World Flora Online (WFO) Begonia treatment (http://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-4000004308). Unfortunately, similar resources are lacking for many other plant lineages.

4.2 Occurrence data quality

The research approach in this study relies heavily on the quality of the occurrence data obtained through field surveys and historical records. The study took advantage of substantial efforts that were taken to document Begonia species across Thailand. However, there were some limitations due to the lack of detailed geographical information in certain historical records. The resulting inaccuracies in occurrence data need to be addressed through targeted field surveys aimed at improving the precision of geographic locations. Furthermore, some regions of Thailand require further field surveys to overcome the difficulties in data collection, particularly for species with specific ecological preferences, such as those that grow on poorly accessible rock outcrops. Another problem is the absence of continuous monitoring to confirm the ongoing existence of these species at previously recorded locations, which is especially important for older records. Finally, the utility of occurrence records could be greatly enhanced by linking informative metadata, such as details about the ecosystems where certain species are found and the number of mature and/or young individuals observed. For some occurrences, this highly valuable data is available, but it is not the norm. We suggest that future research efforts should establish protocols to consistently gather and incorporate this metadata to improve the overall quality and applicability of the occurrence data.

4.3 Assessing vulnerability to extinction

The study set out to tackle the challenge of utilising occurrence data to assess the vulnerability of Thailand's Begonia species to extinction threats. The assessment employed corresponds to Criterion B of the IUCN threat status assessment protocol. However, the full application of the IUCN protocol is often constrained by the limited evidence available for many species. Despite this limitation, the results of these simplified assessments were largely consistent with previously published evaluations. Our data reaffirmed the trend that the majority of Begonia species in Thailand are vulnerable to extinction threats, although not all species fall into this category—B. hatacoa Buch.-Ham. is arguably the most notable exception. While the Begonia treatment presented in World Flora Online lists this species as Least Concern, our assessments using the AOO (Endangered) and EOO (Vulnerable) criteria categorised it as threatened in Thailand. However, this species is not endemic to Thailand, which may explain the discrepancy between our assessment and the global status. This difference highlights the influence of geographic scope on threat assessments. Given the lack of demographic data for many species, further refinement of these vulnerability assessments remains challenging.

4.4 Assessing the effectiveness of current conservation measurements

Thailand's protected areas provide substantial resources for in situ conservation of Begonia species. Only seven species had no occurrences within protected areas. In contrast, 21 species had at least 50% of their occurrences in protected areas. Focusing specifically on very rare species—those with only one to three known locations in Thailand—the study found that seven species were without a recorded location in protected areas. This includes four of the 11 species known from a single location in Thailand, two of the 11 species with two locations in Thailand, and one of four species with three locations in Thailand. However, it is important to note that seven species with a single known location are indeed found within protected areas, as are three out of the 11 species with two known locations. Among the 24 species endemic to Thailand, five lacked protection from the country's protected areas, whereas four species had all their known locations within these areas.

Regarding biodiversity hotspots, the study identified only one out of nine hotspots located outside protected areas, further emphasising the critical role these areas play in in situ conservation. Thailand arguably already has substantial resources to protect the Begonia diversity via in situ interventions. In contrast, ex situ capacities are still underdeveloped despite the existence of several well-managed botanical gardens. In spite of their high ornamental value and the possibility of reproducing many species vegetatively, no evidence was found of any targeted cultivation program focusing on reproducing individuals for conservation purposes. Furthermore, there is a notable absence of initiatives to protect the genetic diversity of these species through seed banks or tissue banks.

4.5 From priority species lists towards conservation actions

By employing relatively straightforward criteria—such as the range criterion categories AOO and EOO, the number of known locations, endemism, and percentage of locations within protected areas—the study established a priority species list for conservation interventions (Supporting Information: Files S2 and S3). Four species were ranked on the top due to particularly high conservation concerns: (1) B. bella Phutthai, B. fulgurata, B. pengchingii, and B. sirindhorniana. These species are all endemic to Thailand, known from only one or two locations and fall under the Critically Endangered or Endangered categories based on the range criteria. Moreover, all known occurrences of these species are outside protected areas. Other endemic taxa appear to be under less immediate threat, primarily due to some level of conservation intervention through their presence within protected areas. For instance, B. saxifragifolia is endemic to Thailand and is classified as Least Concern because it is known from a total of 11 locations. However, the fact that only two of these locations are within protected areas raises concerns about the ability to protect this species. Two species with all occurrences outside protected areas were not endemic to Thailand. For such species—non-endemic with all occurrences outside protected areas—conservation actions might require collaboration with neighbouring countries. Such collaborations are particularly pertinent for species occurring in Thailand's Peninsula floristic region and the Malay Peninsula, involving 11 shared species. Likewise, collaboration is necessary for species shared with Myanmar (27 species) and Lao (12 species).

4.6 Steps forward

Arguably, the main shortcoming of the current inventories of Begonia species in Thailand is the lack of demographic data. Accurate estimates of the number of individuals and regeneration capacity of populations via sexual reproduction are especially important for evaluating the extinction threats for species highlighted as a priority. Targeted field surveys have to be carried out to gather this data, which will improve threat assessments and guide more effective conservation interventions. Another significant gap is the absence of information on the genetic diversity of Begonia species in Thailand. An increasing number of studies have explored the genetic diversity of Begonia species (Chan et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018; Nakamura et al., 2014; Tseng et al., 2019; Twyford et al., 2014, 2015; Xiao et al., 2023), but none have focused on species occurring in Thailand. These studies support the hypothesis that many species of Begonia have limited dispersal capacities, resulting in population structures shaped by limited gene flow and random genetic drift. These genetic insights need to be taken into account when designing conservation interventions that protect the genetic integrity and genomic health of the conserved species (Allendorf et al., 2010; Theissinger et al., 2023).

To address these conservation gaps, a multi-component strategy is required. First, the existing in situ conservation interventions must be expanded. The required capacity building may be achieved by expanding the existing protected areas to cover currently unprotected biodiversity hotspots in Northern Thailand and implementing the concept of micro-reserves (Fos et al., 2017; Laguna et al., 2013). Given the narrow ranges and highly specialised ecosystem preferences of priority species, micro-reserves focused on unique habitats such as karst outcrops—home to species such as B. exposita, B. pengchingii, and B. surculigera—are likely to be effective. The focus on the habitat of a single species resolves the conflict between providing for threatened species and the provision of natural resources, for example, land, to the local communities. However, translocation from highly threatened locations to sites in protected areas may have to be considered (Diallo et al., 2023). In addition to in situ measures, there is an urgent need to establish resources for ex situ conservation. This should include cultivation programmes in botanical gardens and the creation of germplasm banks for long-term protection, for example, seed banks, tissue culture banks and DNA banks (Elliott & Greuk, 2022). Successful reproduction in ex situ programmes may also facilitate the translocation of species into restored habitats, such as karst landscapes rehabilitated after mining activities end. By addressing these gaps, Thailand can strengthen its conservation capacities and move closer to achieving the goal of zero species extinction for its unique Begonia diversity.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Sirilak Radbouchoom: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; writing—original draft. Marjorie D. delos Angeles: Conceptualization; methodology; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Thamarat Phutthai: Data curation; funding acquisition; investigation; writing—review and editing. Harald Schneider: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the financial support provided in form of scholarships to SR by the Chinese Government Scholarship program (CSC Scholarship) and MA by the Alliance for International Science Organization (ANSO). We also acknowledge the financial support given to HS by the Yunnan Province Science and Technology Department (202101AS070012), Yunnan Revitalisation Talent Support Program “Innovation Team” Project (202405AS350019), and 14th 5-Year Plan of the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences (E3ZKFF8B01). Our sincere appreciation goes out to the curators of Bangkok Herbarium, Forest Herbarium, and Queen Sirikit Botanic Garden Herbarium for their generous permission to access their specimen collections. We also express our gratitude to the staff of the Forest Herbarium (BKF), Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plants Conservation, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. We thank Dr. Somran Suddee, and Dr. Naiyana Tetsana for providing the valuable data from the field survey, and Mr. Suphat Prasobsin, Miss Thanee Sang-on, and Miss Sinatchaya Sayuanprung from Mahidol University, as well as Dr. Benjamin Blanchard and Zhou Cong for their invaluable assistance. We express our gratitude to the editor, reviewers and English editor for their valuable comments and recommendations, which have significantly improved the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The research does not involve any experiments involving animals or humans.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data contain the occurrences of threatened rare and endemic species. Thus, the data that support this study's findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.