Moving beyond the pathology of policies pushing species toward extinction: The case of spectacled flying foxes in Australia

摆脱将物种推向灭绝的政策症候——以澳大利亚眼镜狐蝠为例

Editor-in-Chief & Handling Editor: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz

Abstract

enThe rate of extinction is increasing with little reversal of negative trends, prompting a need for conservation scientists and practitioners to rethink approaches to aid the recovery of threatened species. Many extinctions could be prevented if impediments to protecting these species were addressed effectively. This article considers how current policies and practices are failing an endangered species and how biodiversity conservation is fraught with barriers such as rhetorical adoption, policy dismantling, circumvention of legislative obligations, and the deliberate disregard of scientific evidence. These issues became evident while researching the endangered Spectacled Flying-fox (Pteropus conspicillatus Gould 1850), which, despite over a decade of recognized decline, received little attention from authorities who could have acted to stabilize or recover its populations. Recovery plans are often the primary means used by many countries to help threatened species recover and typically fall under government responsibility for implementation. For these plans to be effective, they should be mandatory, well-funded, and subject to stringent monitoring and reporting requirements. However, the implementation of such plans is often inconsistent, with many not meeting these criteria. The scientific basis for recovery actions is usually well-researched, although uncertainties around outcomes remain since these actions are experimental and success is not guaranteed. The failure to implement recovery plans can be highly frustrating for conservation scientists and practitioners, often stemming from policy failures. For those involved in conservation research and practice, learning how to identify and overcome policy impediments would help to ensure the successful implementation of recovery plans. Vigilance is required to ensure that recovery teams function effectively, that recovery actions are executed, that decision-makers are held accountable for endangering species, and that legislation includes merits review provisions to challenge poor decision-making. Conservation scientists who monitor species of concern are often best placed to track the progress of recovery actions. When they detect insufficient action, they have a responsibility to intervene or to notify the responsible authorities. Ultimately, government policies should prioritize the protection of threatened species over economic and political interests, recognizing that extinction is irreversible and the stakes are high for biodiversity conservation.

摘要

zh物种灭绝的速度越来越快且几乎没有逆转的趋势,这促使保护生物学家和相关从业人员重新思考如何恢复受威胁物种的方法。如果能有效解决保护这些物种所遇到的困难,许多物种的灭绝是可以避免的。本文探讨了当前的政策和实践是如何未能保护濒危物种的,以及生物多样性保护面临的各种障碍,例如仅口头的采纳、政策的拆解、规避立法义务以及故意无视科学证据。这些问题在研究濒临灭绝的眼镜狐蝠(Pteropus conspicillatus Gould 1850)时变得明显起来。尽管该物种种群已被认定衰退了十多年,但相关部门却几乎没有采取任何措施来稳定或恢复种群。

恢复计划通常是许多国家帮助受威胁物种恢复种群的主要手段,通常由政府负责实施。为使这些计划有效,它们应该是强制性的、资金充足的、并且符合严格的监测和报告要求。然而,这些计划的实施往往并不一致,许多计划并不符合这些标准。尽管制定恢复行动的科学依据通常经过了充分的研究,但由于这些行动是具有实验性质的,结果仍存在不确定性,无法保证一定会成功。恢复计划实施的失败可能会让保护生物学家和相关从业人员非常沮丧,而这通常源于政策上的失误。对于那些参与保护研究和实践的人来说,学习如何识别和克服政策障碍将有助于确保恢复计划的成功实施。相关人员需要保持警惕,确保实施恢复计划的团队有效运作,恢复行动得到执行,决策者对危及物种的行为负责,并保证立法中包含案例优劣审查条款,以挑战错误决策。监测所关注物种的保护生物学家往往是监督恢复行动进展的最佳人选。当他们发现行动不力时,有责任进行干预或通知相关部门。

最后,政府政策应将保护受威胁物种置于经济和政治利益之上,认识到物种灭绝是不可逆的,保护生物多样性事关重大。【审阅:于潇雨】

Plain language summary

enSpecies extinctions are increasing at an alarming rate. Although listing species as endangered on national and international registers is an important step, it does little to help their on-ground recovery. Many extinctions could be prevented if recovery actions, based on scientific information, were actually implemented. However, these actions frequently face obstacles due to government reluctance, lack of funding, and insufficient resources.

This article examines how policy and practice failures have contributed to the plight of an endangered species and discusses how biodiversity conservation is often undermined by mere lip service to plans, the dismantling of good policy, the avoidance of legal responsibilities, and the disregard of scientific evidence.

Recovery plans are often the main strategy employed to aid endangered species recover. While the science behind recovery actions is usually robust, there are inevitable uncertainties about their success, especially since these actions are usually untested before a species begins to decline.

The implementation of these actions is of utmost importance, and understanding and overcoming policy barriers is also essential to ensure that recovery plans are carried out effectively.

简明语言摘要

zh物种灭绝的数量正在以惊人的速度增加。虽然将物种列为国家或国际濒危物种是重要一步,但这对它们的实地种群恢复几乎没有帮助。如果基于科学信息的恢复行动得到切实执行,许多物种的灭绝是可以避免的。然而,由于政府缺乏主动性,缺少资金和资源,这些行动经常面临障碍。

本文探讨了政策和实践的失误是如何导致一个濒危物种陷入困境的,并讨论了生物多样性保护是如何经常被仅限于口头承诺、拆解良好政策、规避法律责任以及漠视科学证据所破坏的。

恢复计划通常是帮助濒危物种恢复种群的主要策略。虽然恢复行动背后的科学依据通常是可靠的,但其最终成功与否仍存在不确定性,特别是因为这些行动在物种开始衰退之前通常未经过测试。

这些行动的实施至关重要,而理解和克服政策障碍对于确保恢复计划的有效实施也同样重要。

Practitioner points

en

-

Conservation scientists working with endangered species must recognize that decision-makers may not hold the same conservation priorities.

-

Conservation scientists have a role in negotiating policy decisions, but they must either have the negotiating skills to win often difficult and rhetorical arguments or engage skilled negotiators who understand negotiating tactics.

-

Negotiating effective conservation outcomes that impact endangered species depends on understanding competing interests and the lobbying power among stakeholders, appreciating societal willingness to protect biodiversity, making informed judgments about acceptable risks, and addressing uncertainties associated with inadequate information.

实践者要点

zh

-

从事濒危物种研究的保护生物学家必须认识到,决策者可能对保护的重点持不同观点。

-

保护生物学家如果想要在政策决策方面发挥作用,那么他们要么必须具备谈判技巧,以赢得往往是困难且激烈的争论,要么聘请懂得谈判策略的熟练谈判者。

-

谈判影响濒危物种的有效保护结果取决于理解利益相关者之间的利益竞争和游说能力,了解社会保护生物多样性的意愿,对可接受的风险做出明智的判断,并解决由于信息不足造成的不确定性。

1 INTRODUCTION

Global populations of threatened species continue to decline (SCBD, 2020), signaling we are amid the sixth extinction crisis (Strona & Bradshaw, 2022), this one anthropogenic (Dirzo et al., 2022). In response, multilateral agreements such as the Convention on Biological Diversity commit governments to take decisive action to protect species. These agreements are supported by targets and tools, including the IUCN Red List of Species, the Aichi Targets, and the Post-2020 Biodiversity Framework. The Red List includes more than 42,000 threatened species, and Australia alone lists over 2000 species as threatened. Of these, 110 have been listed as “Priority Species,” which the federal government has earmarked for “targeted effort and resources.” Despite these mechanisms, the implementation of species protection through national laws and actions has regularly been unsuccessful (Howell & Rodger, 2018; Santangeli et al., 2013; Scheele et al., 2018; Wistbacka et al., 2018), and the Aichi Targets have not been met by any country (Díaz et al., 2019; SCBD, 2020). Considerably greater efforts are needed, and nation-states need to revise and enforce legislation, policies, and recovery actions (Bolam et al., 2020; Evans et al., 2016; McCormack, 2018; Wood & Flahr, 2004).

Recovery plans have been used for decades (e.g., Ferreira et al., 2019; Malcom & Li, 2018; Pierson et al., 2016) to help threatened species recover and aim to prevent extinctions (Hoekstra et al., 2002). These plans are not always successful (Wistbacka et al., 2018), yet they remain essential for species recovery efforts (Malcom & Li, 2018). Failures have been attributed to poor alignment of recovery actions with scientific evidence, inadequate knowledge of recovery needs (Delach et al., 2019; Kraus et al., 2021; Ng et al., 2014; Weiss et al., 2021; Wistbacka et al., 2018; Woinarski et al., 2017), and insufficient funding (e.g., Luther et al., 2016). This article addresses another critical issue: the complete failure to implement recovery plans, which, while not uncommon (Malcom & Li, 2018), is often poorly examined.

To illustrate the problem of nonimplementation, we present our understanding of the causes of failures to implement the recovery plan for the endangered Spectacled Flying-fox in North Queensland, Australia. Understanding impediments to implementation requires substantial investigation—a task we (and others) have undertaken over the past few years for the Spectacled Flying-fox. While the specific circumstances may vary across jurisdictions due to different laws and administrative environments, understanding these impediments is essential if declines are to be reversed. The distinction must be made between understanding impediments or failure to implement recovery plans and assessing whether the actions recommended by scientists or practitioners have been successful (Gerber, 2016; Malcom & Li, 2018).

Inadequate or inappropriate actions have been previously identified in the conservation efforts for Australian species. Species such as the Bramble Cay Melomys (Melomys rubicola) and the Christmas Island Pipistrelle (Pipistrellus murrayi), both of which are now extinct, had recovery plans in place that failed to prevent their decline (Woinarski et al., 2017). Similarly, another species with a recovery plan, the endangered Southern Black-throated Finch (Poephila cincta cincta), is still suffering population decline due to loss of habitat. Alarmingly, most of the 775 applications to approve the clearing of its habitat have been successful (Reside et al., 2019). The reasons for the lack of effective action in these cases are probably as complex as those for the Spectacled Flying-fox. However, we propose that the elements we address in this article are likely to be common factors across these situations. By identifying and understanding these issues, this article aims to alert other conservationists and stakeholders to the systematic obstacles that impede effective government action in species conservation.

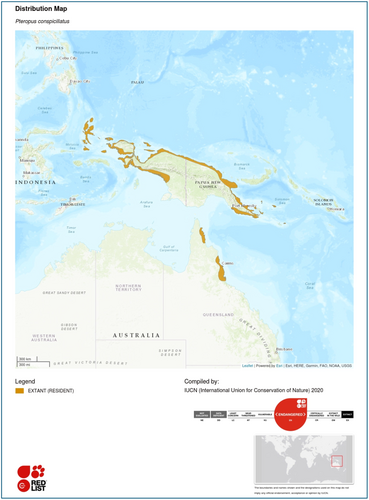

The Spectacled Flying-fox, also known as the Spectacled Fruit-bat, comprises two subspecies. The first, Pteropus conspicillatus conspicillatus Gould 1850, is found in Australia and extends to some areas in the coastal forests and islands of Papua New Guinea. The second subspecies, Pteropus c. chrysauchen, is exclusive to New Guinea and eastern Indonesia (Flannery, 1995a; Fox, 2006; Helgen, 2007; Jackson & Groves, 2015) (Figure 1). The Australian and New Guinea populations of P. c. conspicillatus may have limited genetic interactions, but this has not been studied (Richards & Hall, 2002). The closely related Black Flying-fox (Pteropus alecto) is known to move between Australia and New Guinea (Breed et al., 2010), suggesting potential for cross-regional genetic exchange. The status of the New Guinea population of P. conspicillatus is not known (Fox, 2006). This article focuses exclusively on the Australian population of the Spectacled Flying-fox.

The Spectacled Flying-fox is unique among the Australian mainland flying-foxes as the only species specialized to the Wet Tropics Bioregion. It is a keystone species, contributing to pollination and seed dispersal processes (Flannery, 1995b; Mokany et al., 2014; Parsons et al., 2006) and supporting the maintenance and evolution of Wet Tropics World Heritage Area values (Mokany et al., 2014; Westcott et al., 2001). The Australian population is confined to the Wet Tropics and northern Cape York Peninsula (QDERM, 2010; Shilton et al., 2008), ranging from Cape York to Mackay in central Queensland (Richards, 1990).

The Australian population of Spectacled Flying-fox declined from 326,000 to 78,000 between 2004 and 2017, apparently due to cyclones, habitat loss, and persecution (Threatened Species Scientific Committee, 2019; Westcott et al., 2018). Over the period from 2004 to 2016, the population decreased by 75% (mean r = −0.12 yr−1) (Westcott et al., 2018). Without management intervention, the population is likely to remain low (Fox et al., 2008; Westcott et al., 2018). In late 2018, 23,000 individuals died (MK, unpublished data) during a heat event (Bureau of Meteorology, 2018). This was the second largest flying-fox mass death event recorded, and it was unprecedented for the Spectacled Flying-fox (Westcott et al., 2018). Tropical species like the Spectacled Flying-fox are more susceptible to climate extremes than nontropical ones as they live closer to their thermal limits (Deutsch et al., 2008; Sheldon, 2019). Flying-foxes are highly vulnerable to temperatures above 42°C (Welbergen et al., 2008) and struggle to cope with temperatures above 38°C when combined with high humidity (Briscoe et al., 2019). As climate change progresses, such extreme temperature events are expected to become more frequent, longer, and more severe (Chesnais et al., 2019; CSIRO and BoM, 2022; IPCC, 2021). These meteorological changes are also linked to an increase in cyclone intensity (McInnes et al., 2015).

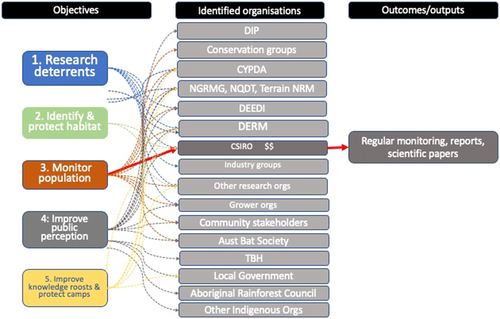

A Recovery Plan for the Spectacled Flying-fox was prepared by two experts in the field, underwent reviews by the relevant government departments and the public, and was officially approved and published in 2010 (QDERM, 2010). Despite these measures, no active recovery team was established until 2020 by volunteers, effectively at the end of the plan's intended lifespan. Throughout this period, apart from population counts that demonstrated a significant decline (Westcott et al., 2018), the only actions undertaken, principally by volunteers, were incidental to the plan. These included efforts to reduce barbed wire entrapment and improve crop netting (Maclean, 2011). There may have been some shortcomings in identifying or clearly articulating actions, but even definitive works, such as the Action Plan for Australian Mammals (Woinarski et al., 2014), downplayed the threat of climate change. Furthermore, the most recent paper on the decline of the Spectacled Flying-fox (Westcott et al., 2018) underplayed extreme heat event potential, identifying only “other extreme climate events” less than a year before 23,000 animals died in one extreme climate event. The conservation scientists who drafted the original recovery plan were not engaged further in implementing their identified actions, leaving the responsibility to the designated authorities, who failed to take effective action (Table 1). A possible issue was that, although necessary actions were identified in the plan, it did not specify which tasks were to be carried out by identified organizations, the funding required for each task, or the priorities among each task (Figure 2). Compounding these challenges, obtaining support from government bodies to take action may have been complicated by the Spectacled Flying-fox's reputation for eating commercially grown fruit, defecating in swimming pools, and carrying some zoonotic diseases (Thiriet, 2005), each negatively affecting agricultural, community, and political support for their conservation (Mo et al., 2024; Preece, 2023).

| Major policy suboptimalities | Recommended state | Constraints |

|---|---|---|

| EPBC Act revision delayed and not addressing major factors in endangered species recovery | Comprehensive revision of EPBC Act | Reluctance of government to implement recommendations of Samuel review and competing interests from nonconservation sectors |

| Recovery plans not obligatory for endangered species, open to discretion of the minister | Make recovery plans for endangered species a legislative requirement, rather than discretionary | Ministers’ reluctance to give up discretionary powers |

| Implementation of recovery plans is not mandatory | Legislation should require that recovery plans must be implemented in a timely manner, including allocated funding | Governments and departments likely to be unprepared to make implementation mandatory because of cost and other implications |

| Lack of reporting on outcomes of recovery plans | Legislation or policy should require periodic (2–3 years) public reporting on outcomes of actions taken and reasons for not taking actions | Departments may be reluctant to commit to reporting and monitoring of reporting |

| Failure to review recovery plan at legislated 5-year interval, resulting in failure to update plan in light of new evidence or situations | Departmental officers are accountable for ensuring review as required under legislation | Reluctance to be accountable |

| No requirement to have a recovery team in place to manage implementation of recovery plan | Departmental obligation to ensure active recovery teams are in place for endangered species | Lack of incentive within departments to ensure recovery teams are active |

| Lack of transparency on budget allocations to actions on endangered species | Requirement that budget allocations to endangered species are made public | Ministerial and departmental reluctance to reveal budget allocations |

| Decision-makers are not accountable for their actions | Federal and State legislation mandates accountability for decisions on endangered species | Reluctance to require decision-makers (officers and ministers) to be accountable for their decisions even those that may affect the survival of species |

| Recovery plans undergo only limited auditing | Federal and state audit offices are required to audit outcomes of recovery plans | Reluctance to be accountable for outcomes |

| Lack of merits review provision in legislation (only option is judicial review which limits claims to illegalities, not to poor decision-making) | Include provisions for merits review in legislation | Reluctance to allow merits review of decisions, which challenges decision-makers |

| Species assessed as having reached new level of endangerment not formally listed for long periods after assessment | Legislation requires change to listing category within 2 years of scientific evidence of population declines to new level | Removal of discretion of minister or department in listing advice for political purposes |

| Legislation at Federal and state levels in need of revision to account for current understandings of matters affecting endangered species, including climate change | Revise Federal legislation to reflect the Samuel, 2020 review; revise state legislation accordingly | Reluctance of ministers and departments to revise legislation, sometimes because of political implications |

| Economic and political arguments in decisions about endangered species carry equal or greater weight than arguments that could cause species’ extinction or further jeopardy | Endangered species’ survival takes precedence over economic and political arguments | Reluctance to relinquish prioritization of economic and political considerations over endangered species’ survival |

- Abbreviation: EPBC Act, Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

Multiple organizations were identified in the plan as those who would take action, but with the exception of monitoring activities, most were not specifically tasked with undertaking actions, nor did they have recovery actions included in their operational agendas (Figure 2). The pale dashed arrows suggest the tenuous and nonexplicit linkages between objectives, actions, tasks, and responsibilities. The solid red arrows show the specific targeted monitoring action that incidentally demonstrated the decline of the Spectacled Flying-fox (see Table 1 for meanings of acronyms).

With the aim of evaluating the role of scientists and practitioners in threatened species recovery, we critically evaluate the case of the endangered Spectacled Flying-fox in Australia (Figure 3). We make reference to the barriers preventing real action in similar cases and interdisciplinary examples from relevant literature. Specifically, we illustrate the failure of successive governments to protect the Spectacled Flying-fox despite protective legislation, show that decisions over decades have led to heightened risks, and demonstrate that scientific advice has had only a marginal effect in influencing decision-making. We conducted a literature review limited to policy and other impediments to the implementation of recovery plans and actions because we felt that this is one important area that is often poorly investigated by conservation scientists but is essential if recovery actions are to be implemented. We consider how rhetorical adoption (to appear to be taking action when real action is not intended) and passive resistance (indifference by responsible governments despite reported threats) (Morrison et al., 2020b) might lead to failures in implementation.

2 METHODS

To investigate the impediments to policy effectiveness in the conservation of endangered species, we conducted a comprehensive literature search through the Web of Science. Our search terms focused on endangered species: policy, governance, and recovery plans. The search was guided by key literature identified by Morrison and others (2019a; 2019b; 2020a) and supplemented by additional searches of policy studies literature. We initially screened the abstracts of candidate articles (n = >1000) and selected for review those articles (n = 43) that appeared to contain relevant information and reviewed published policies and practices of government departments. This review was intended to identify key impediments to policy failures when dealing with threatened species, not to conduct a full review of recovery plans. The review was qualitative rather than quantitative. The focus was to unearth insights from other researchers’ experiences in navigating obstacles or frustrations that extend beyond typical disciplinary challenges. The 43 articles we selected for further review addressed those issues that we had already identified while also providing new perspectives on overcoming impediments and avoiding common errors. We also engaged with government officers, reviewed government websites, and explored gray literature to gather information on the actions taken under the recovery plan and the resources allocated for its implementation.

3 OVERCOMING IMPEDIMENTS TO ACTIONS FOR BETTER OUTCOMES

Our literature review revealed various situations from other conservation initiatives and disciplines that provide valuable lessons for resolving impediments to conservation action. It is important for conservation scientists and practitioners to actively engage in transforming the circumstances that impede conservation progress and action. While not all individuals are equipped to undertake certain actions, we believe that everyone should be aware of the factors that limit action and understand approaches for overcoming these challenges.

In the realm of threatened species conservation, recovery plans are fundamental tools designed to guide actions intended to reverse declining trends. However, when these plans fail to be implemented, the causes are often multifaceted. These can include detrimental or poorly framed legislation that may require revision, a misalignment in the priorities of government decision-makers who fail to recognize the value and plight of species, and the sometimes existential nature of population declines resulting from these decisions. Our review identified several key factors that need to be addressed, including the adequacy of recovery planning legislation and processes, instances of deliberate or unintentional inaction, and a lack of accountability. We analyze these issues in the following sections and go on to discuss how they can be resolved. To facilitate a structured discussion, we have compiled what we consider major policy suboptimalities in Table 1. Each of these points will be explored in the following sections.

3.1 Benefits and shortcomings of recovery plans

Two agencies share responsibility for the Spectacled Flying-fox: the Federal Department of Climate Change, Energy, Environment and Water (DCCEEW), and the Queensland Department of Environment and Science (DES). The species is protected under the Australian Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) and the Qld Nature Conservation Act 1992 (NC Act). It has been recognized officially that the EPBC Act requires significant revisions, particularly as it pays no regard to climate change (McCormack, 2018). Furthermore, evaluations of the Act have revealed that it is failing to fulfill its objectives regarding the protection of threatened species (Auditor General, 2020; Samuel, 2020), as it has not prevented recent extinctions (Woinarski et al., 2017). More species are likely to become extinct without urgent recovery actions (Geyle et al., 2018), and decisions are still being made that detrimentally affect species, even those with recovery plans (Reside et al., 2019).

Politics, economics, and prevailing ideologies adversely affect the conservation of threatened species (Czech et al., 1998; Delach et al., 2019; Hintzen et al., 2020; Kraus et al., 2021; Langpap et al., 2018). Conservation efforts have been hampered by significant cuts to environment budgets (ACF, 2021; ANAO, 2020; Evans et al., 2016; Gerber, 2016; Wintle et al., 2019), loss of scientific expertise (Russell-Smith et al., 2015; Turner, 2013), policy dismantling (Morrison, 2017) and politicization (Mulgan, 1998; Wright et al., 2021), and reduced capacities of public services (Head, 2019). While these problems are beyond the scope of conservation scientists’ responsibilities, knowing that they exist helps inform how scientists respond.

Conservation actions are essential for the recovery of threatened species (Malcom & Li, 2018). In Australia, recovery plans for threatened species were mandatory until 2006 (EPBC Act, 269AA). They contained detailed actions, identified organizations to take action, and provided indicative budgets. However, in 2006, the legal requirement shifted from mandatory recovery plans to mandatory Conservation Advices (EPBC Act s266B(1)). Unlike recovery plans, Conservation Advices are designed to offer grounds for listing threatened species but do not specify detailed actions, assign responsibilities, or allocate budgets (Walsh et al., 2013). While Conservation Advices can be updated more quickly than recovery plans, this flexibility comes with significant drawbacks. They are less permanent, more susceptible to arbitrary amendments with less scrutiny, and do not provide the details of required actions, budgets, and so on. Importantly, the legal framework stipulates that government declarations must “not make declarations that are inconsistent with any recovery plan" (s268), ensuring some level of consistency and protection. In contrast, there is no such constraint under a Conservation Advice as the minister has only to “have regard to any approved conservation advice” (s34D). This shift is indicative of broader policy dismantling trends, which have detrimentally affected conservation efforts by reducing the action, resources, and finances available. This issue has likewise constrained actions taken for the conservation of the Great Barrier Reef and delayed action on global warming (Morrison, 2017).

Recovery plans help drive recovery action and investment (Legge et al., 2018; Taylor et al., 2011; Walsh et al., 2013; Woinarski et al., 2017), and although their success can vary (Bottrill et al., 2011; Buxton et al., 2020), the absence of recovery plans has been linked directly to increased risks of extinctions (Legge et al., 2018). These plans provide comprehensive strategies for species protection and are designed to span multiple election cycles, which reduces the opportunity for political manipulation. Species that are covered by recovery plans are more likely to recover than species without (Greenwald et al., 2019; Taylor et al., 2005), and successes are associated with conservation actions commonly identified in recovery or management plans (Bolam et al., 2020; Hoffmann et al., 2010; Rodrigues et al., 2006). One example among many identified in Bolam et al. (2020) is the recovery of Gilbert's Potoroo (Potorous gilbertii) due to actions taken in accordance with the recovery plans for this species (Friend et al., 2016; NESP, 2019). A scorecard on actions implemented and outcomes under the plan was published by the Commonwealth for Gilbert's Potoroo (NESP, 2019)—a level of transparency and accountability not afforded in the case of the Spectacled Flying-fox, for which no such report card has been issued. The Australian Government's 2015 Threatened Species Strategy identified 20 threatened species as priorities and subsequently assessed the extent to which actions taken contributed to their conservation (Fraser et al., 2022). However, the Spectacled Flying-fox was not included in these top 20 priority species in 2018, highlighting potential gaps in prioritization and resource allocation.

Even the most well-crafted recovery plans are doomed to fail without adequate funding (Gibbs & Currie, 2012; Greenwald et al., 2019; Hoekstra et al., 2002; Schwartz, 2008). Research has shown there is a positive correlation between the amount of funding and a species’ population trend (Luther et al., 2016; Malcom & Li, 2018). Accessing federal government expenditure information is difficult (Howell & Rodger, 2018; Iacona et al., 2018; Wintle et al., 2019), but funding allocation for Spectacled Flying-fox was said to be predominantly for population counts and improved radio tracking technology (around AU$1.5 M in 2012–2016; DCCEEW, 2024) to understand drivers and dynamics of Hendra virus carried by flying-foxes (Westcott et al., 2015). This funding (in the order of AU$12 M over 4 years; DCCEEW, 2024) was not directly linked to the recovery actions outlined for the Spectacled Flying-fox. Instead, it was part of broader Commonwealth and state government initiatives (mostly agriculture departments) aimed at Hendra virus research, including “Hendra-virus, human health, and Flying-fox related projects” (DCCEEW, 2024). Specific funding was not made available for most of the 25 key actions identified in the recovery plan (QDERM, 2010). These actions included identifying and mapping foraging areas and roosting requirements, protecting important camps, investigating low-cost crop deterrent systems, and improving public perception through multiple means (see Table 1).

The implementation of plans suffers from inconsistent reporting (Wintle et al., 2019) and a general lack of accountability (Bottrill et al., 2011). While implementation is ultimately the government's responsibility, there appears to be no administrative means to ensure that action is taken. This issue is illustrated by the legal requirement (EPBC Act s279) to review the recovery plan for the Spectacled Flying-fox after 5 years going unmet. Recovery plans, once made, are required to be “in force” (EPBC Act s273), but there is no obligation for plans to be “implemented” (Woinarski et al., 2017), contrasting with the US Endangered Species Act 1973 s.4(f)(1) which requires that they are implemented; we are aware that this requirement is not always met and has required litigation for the Act to be effective (Langpap, 2022). The combined effect of these shortcomings means that organizations identified as responsible for taking action often lack specific guidelines on what exactly is expected of them, the funding and resources available, and the priorities among identified actions and tasks. There is no single organization designated to follow up on these activities, resulting in limited coordination and oversight.

3.2 Shortcomings of state and national legislation

Legislation can be effective in facilitating recovery (Bolam et al., 2020; Greenwald et al., 2019), but it is often hindered by administrative processes. Slow processes worked against the conservation of the Spectacled Flying-fox: it was listed under the EPBC Act as vulnerable in 2002 (Thiriet, 2005), “near threatened” in 2012 (Dennis, 2012; Woinarski et al., 2014), and nominated as endangered in 2015 but not listed until 2019. The endangered listing would have provided greater protection than the previous vulnerable listing. Delays in updating the status were attributed to pressure from the agricultural industry and politicians (McGrath, 2001), reflecting a broader pattern where industrial lobbying pressure, such as that by the fossil fuels industry to avoid listing the Great Barrier Reef as World Heritage in Danger (Morrison et al., 2020b) and to avoid action on climate change (Wright et al., 2021), obstructs conservation efforts. These delays are similar to the avoidance, alteration, or misuse of conservation measures noted in other contexts (Miller et al., 1994). Delays can have severe consequences (Ferreira et al., 2019), including the extinction of species (Greenwald et al., 2019). Decisions to postpone listing may mean that statutory action is no longer required (Whritenour Ando, 1999). Slowness in listing species is essentially passive resistance (Morrison et al., 2020b) as it reinforces low priority for funding and action.

Action on threatened species can be stalled by rhetorical adoption (Fisher & Brown, 2014; Morrison et al., 2020b). This phenomenon is characterized by the publication of recovery plans that are subsequently not implemented and the insufficient or complete lack of funding for necessary conservation actions (e.g., Greenwald et al., 2019; Waldron et al., 2017; Wintle et al., 2019). Australian federal expenditure on biodiversity was 28% lower in 2021 than in 2013 (https://budget.gov.au/; accessed June 14, 2021), and staff numbers in the environment department halved from 2013 to 2019 (ANAO, 2020), both of which affected conservation funding.

The legislative amendments in 2006 that made recovery plans discretionary rather than mandatory also increased the minister's powers to consider socioeconomic and political factors more heavily in conservation decisions. This shift introduced a level of discretion that can discount the conservation status of a species, including its risk of extinction. It has been argued that ministers (and presumably other decision-makers), in exercising a socioeconomic prioritization veto over decisions affecting threatened species, can face public shaming (Farrier et al., 2007), but we argue that the potential for further jeopardizing an endangered species may not perturb them. For instance, from 2013 to 2020, 85% of the Spectacled Flying-fox roost trees within a nationally important camp in the Cairns City central business district in far north Queensland were destroyed, and the animals “dispersed” to enable commercial development, with the Government's approval (http://epbcnotices.environment.gov.au/referralslist/; e.g., 2019-8424, accessed October 18, 2020). This action was contrary to the intentions of the EPBC Act and mirrors earlier detrimental decisions (McGrath, 2001; Thiriet, 2005). In the landmark 2001 “Flying-fox case,” the first trial under the EPBC Act, an injunction to prevent further government-approved electrocution of SFF was granted by the Federal Court, ruling that such actions were contrary to the legal protections afforded to the species (McGrath, 2001) and establishing legal ramifications of allowing damage to SFF (McGrath, 2001, 2008). Despite this legal precedent, similar decisions are still being made two decades later with no repercussions for the decision-makers, as the current legal framework imposes no penalties for such decisions. The “Statement of Reasons” regarding the dispersal of the Spectacled Flying-fox found that the action “is likely to have a significant impact” yet it was argued that there was “sufficient information to conclude the proposed action is unlikely to have unacceptable impacts” (http://epbcnotices.environment.gov.au/referralslist/ No 2019/8424, Clauses 41, 62; accessed September 7, 2020), despite contrary evidence which was not mentioned (Edson et al., 2015; Roberts & Eby, 2013). These contradictory statements in the “statement of reasons” could be grounds for a merits appeal, which we discuss below.

3.3 Conservation scientists’ roles in policy

The intertwining of science and politics—often termed “politicization of science” and “scientification of politics”—has been recognized for some decades as an ideological power-play that has moved away from the traditional paradigm of scientific rationality and the ideal of “speaking truth to power” (Hoppe, 1999). Conservation scientists can play roles in changing some of the detrimental circumstances leading to inaction and policy inertia on threatened species, although they may be limited by their employers or their concerns about funding or career paths (Driscoll et al., 2020), or even adverse reactions from peers (Morton, 2017). The decision to take action is highly personal and is determined by many factors, ultimately coming down to subjective decisions and personal circumstances. Conservation actions may also change according to the matter at hand and how confident the scientists are with their roles. In contrast with Morton's views that taking “value positions leaves the discipline vulnerable to criticism that it comprises just another interest group,” Cullen (2006) argues that scientists may “‘hold strong values about desirable outcomes and should be welcome in” political debates. In some circumstances, it may be necessary for conservation scientists to refute “junk science” that is presented in decision-making forums (Cullen, 2006). Ultimately, it is a decision that has to be made by scientists as to whether or not they take active positions on matters.

- 1.

failing to define endpoints: what is the endpoint for a threatened species—population stability, recovery, to what level, how it will be measured;

- 2.

mixing means and ends: ends are the “things that matter” or endpoints, whereas means are the policies and management strategies to achieve them;

- 3.

ignoring the management context: stakeholders need to determine what is desired from management priorities;

- 4.

making lists instead of indicators: we reinterpret this mistake as identifying what was done rather than what has been achieved (in terms of species recovery, for instance);

- 5.

failure to link indicators to decisions: how decisions affect outcomes;

- 6.

confusing value judgments with technical judgments: interpretation of data is a technical judgment that should be made by scientists, what to do about it is a value judgment that scientists may contribute to, provided that they acknowledge the differences;

- 7.

substituting data collection for critical thinking: ensure that data availability does not drive what are the more important indicators of success or otherwise, and use expert judgment elicitations to help organize knowledge around critical thinking; and

- 8.

oversimplifying complex biodiversity dynamics and relationships has the potential to affect decision quality and introduce undesirable trade-offs (Failing & Gregory, 2003).

Conservation scientists are often the most aware of the gaps and deficiencies in the knowledge base related to the species or ecosystems they study. This awareness is key because the inherent uncertainties and ambiguities in the science underpinning proposed recovery actions can complicate decision-making processes. Such complexities may even contribute to the failure to prevent extinction or further decline of species, as decisions that may affect a species’ survival are (almost) always made in the face of uncertainties (Woods & Morey, 2008). These factors can lead to a range of reactions from decision-makers who may not be comfortable with the scientific concepts of uncertainty, probability, and ambiguity, so conservation scientists working in decision-making situations need to be sensitive to their audience. We discuss some methods for resolving these issues below.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Overcoming rhetorical adoption

The argument that sufficient scientific information ensures decision-makers will make the “right” decisions and that scientists merely act as “honest broker(s)” (Pielke, 2007) is not supported by evidence (Oliver & Cairney, 2019; Toomey et al., 2017). Politics, economics, and social factors are significant in decision-making processes (Hintzen et al., 2020). Consequently, challenges in species protection cannot be resolved simply by providing more data. Instead, a deeper understanding of the science-policy-politics interface, as well as governance threats and power relationships, is essential (Buxton et al., 2020; Hintzen et al., 2020; Morrison et al., 2020b). Industrial lobbying and regulatory capture hold great sway over decision-making (Morrison et al., 2020b), and deliberative and philosophical obstructions, along with competing socioeconomic interests implicit in failures to protect species (Morrison et al., 2020b), are often underestimated as legislation is inherently political (Whritenour Ando, 1999).

Obstruction and obfuscation in conservation decisions can be constructed, deliberate, and political (Thiriet, 2005). A more nuanced understanding of governance and politics is key (Kraus et al., 2021; Morrison et al., 2019a), as is recognition of the tactics of rhetorical adoption and passive resistance (Morrison et al., 2020b). Decision-making processes are often driven by those with vested economic and political interests and disproportionate power (Gilens & Page, 2014; Head, 2019; Stanzel et al., 2020). Conservation proponents often find themselves with comparatively less influence, especially when economic arguments dominate the discourse (Morrison et al., 2020b). Therefore, scientists need to recognize that their evidence, while crucial, is only one component in a broader decision-making process (Oliver & Cairney, 2019). Recognizing this reality, scientists must strategize on how to effectively influence the outcomes of negotiations and decision-making processes.

Conservation scientists play a role in many of the changes needed to redress the situations that arise from a lack of action on species recovery. While it is understood that not all scientists may wish to take more aggressive actions, and some may not feel suited to such roles, it is increasingly important that conservation scientists broaden their understanding of societal working and what others see as priorities and preferences. Conservation scientists may be required by their employers or by courts of law or merits review panels to present expert evidence in a number of situations, but they may choose to go beyond this to advocate for changes to laws, policies, and practices where they feel they can contribute meaningfully, and their employers do not prevent them.

Effective public engagement (Russell-Smith et al., 2015) and proactive action by scientists are needed (Morrison et al., 2020b). Scientists must be persuasive and adaptable (Oliver & Cairney, 2019), and while advice on how scientists can influence policy is prolific, some is arguably flawed (e.g., Oliver & Cairney, 2019). Conservation scientists with appropriate skills and aptitude (Oliver & Cairney, 2019) need to act as advocates to succeed in policy and practice contexts (Warin & Moore, 2020) and speak to “the language of value and economic impacts” (Dunlop, 2014). Scientists who become involved in conservation or advocacy issues must also develop skills to clearly present and interpret data in terms of specified endpoints and consequences (Failing & Gregory, 2003, p. 129). Discerning what is critical and what may be extraneous in these discussions is important (Rabaud et al., 2020). Moreover, scientists need to recognize when they are acting as issue advocates promoting particular viewpoints rather than presenting objective scientific evidence (Wilhere, 2017). Debates on policy can often become adversarial, and conservation scientists need to be aware that lapses in judgment about the meaning and importance of their arguments can be used by adversaries to demolish even the best parts of presented arguments.

There are a number of proactive measures that conservation scientists can advocate for to overcome policy and administrative barriers to effective conservation action. A pivotal starting point is the reform of recovery plan processes (ACF et al., 2015; Bottrill et al., 2011; Legge et al., 2018; Walsh et al., 2013). Mandating government-approved recovery plans and recovery teams would arguably provide substantial influence in decision-making and ensure commitment over several electoral cycles. Historically, many recovery plans have not been implemented (ACF et al., 2015; Bottrill et al., 2011; Walsh et al., 2013). To address this, implementation should be explicitly required by legislation. Successful plans are commonly led by dedicated recovery teams and champions (e.g., Black-throated Finch Recovery Team, 2007; CoA, 2019; Department of Environment Land Water and Planning, 2016; OEH NSW, 2012), akin to “facilitative leadership” that is essential to good governance outcomes for recovery (Ayambire & Pittman, 2022; Kraus et al., 2021). Where recovery teams are not formed in due course, it should be the responsibility of governments to ensure their formation. Should governments fail in this duty, it becomes incumbent upon the authors of the recovery plans—often conservation scientists themselves—to call governments to account.

Conservation legislation needs revision, as evidenced by the EPBC Act (APEEL, 2017a; Auditor General, 2020; EDO & HSI, 2018; McCormack, 2018; Samuel, 2020). The case study presented here is an example of policy and legislative failures worldwide (Evans et al., 2016). Legislation should require recovery plans to be in force and implemented, accountability of decision-makers, reporting on plan implementation and outcomes, and merits review provisions (which we discuss below). The results of recovery actions should be published periodically so that progress is documented, transparent, and public.

We argue that actions taken to help species recover from their population declines need to become accountable and auditable, perhaps through formal auditing processes as suggested in the Samuel review of the EPBC Act (Samuel, 2020). This change could address recurring failures within ever-changing government departments to schedule and prioritize recovery plans and other recovery actions.

Conservation scientists working on threatened species may be the ones best placed to assess whether sufficient and appropriate action is being taken. As shown in our review, there have been a reasonable number of scientific articles on the failures of recovery plans, but scientific articles are rarely read by decision-makers and, therefore, may not inform their decisions. Thus, conservation scientists need to consider how best to expand the reach of their work, whether through articles published in responsible media, information papers, policy papers, summaries for decision-makers, or a range of other available options.

4.2 Flawed decision or insufficient weight of evidence?

Challenging flawed decisions is fraught with difficulties. Although the EPBC Act has addressed issues related to standing and substantive laws, significant obstacles remain, such as the threat of adverse cost orders and insufficient financial resources (McGrath, 2008). Implementing merits review (McGrath, 2008) could help resolve problems like the ones highlighted in the case of the endangered Spectacled Flying-fox dispersals and roost destruction. The absence of a merits review process is contrary to federal guidelines, which recommend the inclusion of merits review where legislation confers discretionary powers (PM&C, 2017, cl. 5.47). Judicial review is often inadequate in these situations, as it cannot address the poor quality of a decision if the merit of the decision falls outside the jurisdiction of the court (McGrath, 2008). For example, if the decision-maker has “had regard to” relevant matters, as they did in the statement of reasons for allowing the dispersal of Spectacled Flying-foxes in Cairns, despite no evidence to support the judgment, this poor decision is still difficult to challenge in court (APEEL, 2017b; McGrath, 2008, p. 353). Allowing merits review could improve decision-making, as decision-makers would be required to carefully evaluate and formally justify their decisions, enhancing accountability and transparency (McGrath, 2008, p. 353; Samuel, 2020).

While we do not advocate that conservation scientists should themselves initiate merits review action, it may be incumbent upon them to support such actions by providing expert evidence and advice during the merits review process. The evidence presented must be clear, unambiguous, and grounded in robust scientific research. When conservation scientists appear before a merits review panel, they need to understand how to effectively communicate their evidence. The goal is to ensure that those evaluating the merits of the case are not left with any confusion or uncertainty regarding the status and plight of the threatened species in question. Understanding how to present evidence clearly and addressing the full range of issues is imperative, which is the focus of the next section.

4.3 Conservation science is necessary but not sufficient

Scientific evidence alone is unlikely to persuade decision-makers, as social, economic, and political factors also play significant roles (Hintzen et al., 2020). When conservation scientists and practitioners are involved in decision-making processes due to their subject expertise, they must present robust arguments to influence political decisions effectively (Toomey et al., 2017). In presenting scientific information, it is important to avoid common mistakes (Failing & Gregory, 2003). These include not understanding competing interests and lobbying power among stakeholders, underestimating society's willingness to protect biodiversity (Failing & Gregory, 2003; Woods & Morey, 2008), misjudging what constitutes acceptable risk (Offer-Westort et al., 2020), and not accounting for uncertainties associated with inadequate information (Woods & Morey, 2008). A consequence of these mistakes is demonstrated in the case of the Spectacled Flying-fox in Cairns. Despite evidence presented to decision-makers showing that the Spectacled Flying-fox was in serious decline (Westcott et al., 2018) and that proposals to the council and government would destroy what had been identified as “nationally important roosts” (Department of the Environment, 2015), authorities made decisions to disperse the Spectacled Flying-foxes and destroy most of their roosts, albeit in compliance with the code of practice (Department of Environment and Science, 2020). Once these decisions were made, they became entrenched policies, a situation that is not uncommon. Authorities often defend their policies because they feel obligated to defend them, even to the point of disregarding further scientific advice and seeking alternative “expert” opinions that may not be directly relevant to the case at hand (as in other examples Dunlop, 2017; Dunlop & Radaelli, 2018; Warin & Moore, 2020).

Conservation scientists, if presenting to a merits review panel or to a court of law, need to be confident in their facts. They must also recognize that they will be presenting their cases to a nonscientific audience who may not fully understand concepts such as scientific uncertainty, probability, and likelihood of further decline or extinction. Panel members or judges may also hold different, potentially negative, views about the species of interest and the priorities for action. Therefore, conservation scientists must be adept at explaining complex scientific principles in simple, layperson's terms.

5 CONCLUSION: IMPROVING CONSERVATION OUTCOMES

Just as the climate change debate has been characterized as a creeping crisis (Head, 2019), the Spectacled Flying-fox conservation debate has been slow to evolve, even as the population has dramatically declined. Crises can serve as “circuit-breakers” to trigger new thinking and action (Head, 2019). As the Spectacled Flying-fox population may have reached a “tipping point” (as defined in Turner et al., 2020), there is an opportunity to make meaningful gains in its conservation. To succeed in the political arena, we have to actively participate (Kassen, 2011), particularly when the stakes involve the existence of threatened species. The case of the Spectacled Flying-fox exemplifies how current policies have been insufficient in conserving this important species. By learning from this example, conservation scientists and practitioners can implement strategies to achieve better outcomes for other threatened species.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to conception and writing of the article. Noel Preece led the background research and history, literature review, and writing; TMcG contributed his expertise on the law around the Spectacled Flying-fox, and the legal cases cited, and to editing. Maree Treadwell Kerr contributed her expertise on Spectacled Flying-fox and history of interventions, and to editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Professor Tiffany Morrison (now of Melbourne University), Prof. Justin Welbergen, Evan Quartermain, David Westcott and several anonymous reviewers for their insightful and constructive comments at various stages of the manuscript. Members of the National Recovery Team for the Spectacled Flying-fox provided important background information for this article's case study. The supporting institutions are identified with the authors’ names. The target audience is threatened species conservation practitioners and researchers, policy-makers, and legal advisers to governments.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Noel Preece and Maree Treadwell Kerr are members of the Spectacled Flying-fox National Recovery Team. The remaining author declares no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

No data were used for this article.