Can tropical nature reserves provide and protect cultural ecosystem services? A case study in Xishuangbanna, China

热带自然保护区能否提供和保护生态系统文化服务?来自中国西双版纳的案例研究

Abstract

enCultural ecosystem services (CES) play a pivotal role in local natural conservation and management; however, they frequently remain overlooked by policymakers due to challenges in their definition and quantification. These services are particularly relevant to Asia's indigenous populations. Shangyong and Mengla, two tropical forest reserves in the Xishuangbanna region of Yunnan province, China, were selected for an in-depth study of CES in this area. Through village interviews and questionnaire surveys, the varieties of CES and their significance were identified and catalogued. Subsequently, the distributions of different CES types were mapped and modelled based on environmental drivers and hotspots. A conservation priority indicator was then formulated to identify the most critical CES necessitating conservation, as these are susceptible to human disturbances in the absence of protected nature reserves. Our findings indicated that the most commonly recognised CES included wildlife, leisure and recreational, folk and custom, and sense of place and identity. Benefits derived from leisure and recreational, and wildlife CES were predominantly safeguarded by nature reserves. In contrast, folk and custom CES and spiritual and religious CES were less reliant on these reserves due to intrinsic community-based protection. Consequently, while the two tropical forest reserves in Xishuangbanna offer a range of CES, there is a need for differentiated management strategies to foster local support for conservation management decision-making. The inherent conservation initiatives for spiritual and religious CES and folk and custom CES should be leveraged by incorporating or co-managing these sacred sites within our protected area system. Conversely, CES with a higher conservation priority index, such as leisure and recreational CES and wildlife CES, require government-led conservation to safeguard the cultural well-being of local communities. In conclusion, incorporating CES into nature reserve management strategies is crucial across various conservation contexts.

摘要

zh生态系统文化服务(cultural ecosystem services,CES)在当地自然保护和管理中发挥着关键作用,但其定义和量化方法尚面临挑战,因此常常被政策制定者所忽视。CES对亚洲的本土居民来说尤为关切。本研究选取中国西双版纳傣族自治州勐腊与尚勇两处热带自然保护区,对其CES进行了深入研究。通过对当地村民的访谈和问卷调查,对CES及其重要性做了识别与分类。基于环境驱动因素和热点地区,构建模型并绘制不同CES类型的分布图。然后制定了一个保护优先性指数,用于识别最需要保护的关键CES;在无自然保护区庇护的情况下,这些CES容易受到人类活动的干扰。研究发现,最常见的CES类型包括野生动植物、休闲娱乐、民族习俗,以及地方感和认同感。野生动植物CES与休闲娱乐CES主要由自然保护区保障。相比之下,由于自发的社区保护,民族习俗CES和宗教信仰CES对保护区的依赖程度较低。因此,尽管这两处保护区提供了一系列的CES,但有必要对不同CES制定差异化的管理措施,以促进当地居民对保护管理决策的支持。应利用宗教信仰CES和民族习俗CES的自发保护举措,在自然保护地体系内纳入或共同管理自然圣境。相反地,保护优先性指数较高的休闲娱乐和野生动植物CES则需要政府主导的保护,以保障当地社区的文化福祉。总之,将CES纳入自然保护区管理对各类保护情形都非常重要。【审校:刘鹏】

Plain language summary

enCultural services provided by ecosystems are essential for local communities but often overlooked by decision-makers. To better understand these services, this study focused on two forest reserves in Xishuangbanna, China. The study identified various cultural ecosystem services and their importance by talking to villagers and using survey questionnaires. Some of these, like recreational spaces and wildlife, are mostly protected by the reserves themselves. However, others, like local customs and spiritual practices, are protected by the communities instead. The study suggests that local traditions should be integrated into the formal reserve protection plans for better protection, while activities like leisure and wildlife might need more government intervention. In short, considering these cultural services is key when making decisions about nature protection.

通俗语言摘要

zh生态系统提供的文化服务对当地社区至关重要,但常常被决策者忽视。为深入了解这些服务,本研究对中国西双版纳傣族自治州的两处森林保护区进行了研究。通过对村民访谈和使用调查问卷,确定了生态系统文化服务的类型及其重要性。有些类型主要受自然保护区的庇护,如野生动植物和娱乐场所。然而,民俗和信仰由当地社区自发保护。本研究表明,应将当地传统纳入正式的保护区规划,而休闲和野生动植物等文化服务类型可能需要更多的政府干预。简而言之,在做自然保护决策时,须考虑生态系统文化服务。

Practitioner points

en

-

The nature reserves provide and protect some cultural ecosystem services (CES) types, including leisure and recreational, and wildlife, while others, such as spiritual and religious, and folk and custom, benefit from intrinsic community-based protection.

-

The inherent conservation of spiritual and religious, folk and custom CES should be leveraged by incorporating or co-managing these sacred sites in our protected area system. Conversely, government-led conservation is essential for vulnerable CES types, such as leisure and recreational, and wildlife, to ensure the cultural well-being of local communities.

-

Blanket prohibitions in nature reserves may impede CES benefits for local residents; therefore, the perspectives of various stakeholders need careful consideration in nature conservation to garner local support.

实践者要点

zh

-

自然保护区提供并保护了包括休闲娱乐和野生动植物在内的一些生态系统文化服务,而另一些生态系统文化服务,如宗教信仰和民族习俗,则受益于自发的社区保护。

-

应充分利用宗教信仰、民族习俗的固有保护力量,将自然圣境纳入保护地体系或共同管理。相反地,政府主导的保护对于休闲娱乐和野生植动物等脆弱的生态系统文化服务类型至关重要,以确保当地社区的文化福祉。

-

自然保护区的全面禁入可能会妨碍当地居民享受生态系统文化服务;因此,自然保护须切实考虑各利益相关方的观点,以获得当地居民的支持。

1 INTRODUCTION

To enhance the emphasis on ecosystems in policy decisions and management strategies, ecosystem services have often been ascribed monetary values (Costanza et al., 1997; MA, 2005). However, such assessments have been found to frequently overlook other social perspectives on the contributions of ecosystem services to human well-being (Scholte et al., 2015). Masood (2022) notes that evaluating nature in purely monetary terms can harm people and the environment. Therefore, the benefits of nature, beyond simple monetary valuations of ecosystem services, must be identified. Long-term benefits ought to be considered in terms of sociocultural indicators derived from comprehensive interviews with local communities and stakeholders. This sociocultural valuation of ecosystem services is a critical complement to monetary-based ecosystem services valuation (Brown & Raymond, 2007; Scholte et al., 2015).

Traditionally, ecosystem services include supporting, regulating, provisioning and cultural services, which are intrinsically linked to human well-being (Ma, 2005). In 2013 and 2017, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services improved these services, placing greater emphasis on human–nature interactions and nature's contributions to people (NCP) that influence individuals' quality of life (Díaz et al., 2015, 2018). For NCP, the focus shifted towards a context-specific perspective, underscoring the significance of indigenous and local knowledge as well as cultural ecosystem services (CES). In fact, CES or nonmaterial NCP are interwoven with other services or NCP types. For instance, while local food is classified as a provisioning service, it simultaneously embodies the cultural nuances and sentiments of the local population.

Many definitions are currently used for CES, reflecting the ongoing discourse in this field. In our study, the provision of CES intrinsically entails an ecosystem or natural place and the subsequent interaction or relationship between people and this setting, culminating in a discernible benefit (Infield et al., 2015). The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) categorised CES into 10 groups: cultural diversity, spiritual and religious values, knowledge system, educational values, inspiration, aesthetic values, social relations, sense of place, cultural heritage values and recreation and ecotourism. Cultural services, nonbiophysical in nature, serve as the direct link between ecosystems and human well-being. These bring benefits without physical, ecological, or economic functions. Similarly, the outcomes of these benefits elude traditional value accounting yet directly influence policy-making (Chan, Satterfield, et al., 2012).

Since 2001, CES have attracted the attention of both scientists and conservationists. When integrated into conservation strategies, we can achieve more by making moderate compromises to increase local interest and support (Infield, 2001). Cultural services directly impact policy formulation, acting as a mass basis for nature conservation despite their lack of association with material, ecological functions, processes and outputs (Chan et al., 2016; Ncube et al., 2021). Therefore, within the nature reserve system, the additional assessment of cultural service value is crucial (Chan, Satterfield, et al., 2012). In Tanzania, cultural values have bolstered the conservation of forest patches outside designated protected areas (Infield et al., 2017). These interspersed forests, situated between nature reserves, often play the role of ‘stepping stones’ and are preserved due to their spiritual and religious value (Verschuuren & Furuta, 2016; Zhang et al., 2019).

A decade ago, CES research primarily centred on urban green spaces. If solely framed within the contexts of entertainment and eco-tourism, the findings risk being biased, potentially misguiding researchers and policymakers. Although relevant studies have increased in recent years, evaluating CES remains challenging compared to other service types, owing to their intangible and nonconsumptive characteristics. In context-specific conservation, targeted local scale CES assessments prove more relevant for policymaking than those at larger scales (Plieninger et al., 2013; Tengberg et al., 2012).

Considering data accuracy and scale limitations, decentralised data collection and dynamic scenario planning that engages local people can improve public understanding and policy applicability, thereby presenting a novel avenue for research (Costanza et al., 2017). Various methods have been devised to map or assess CES that draw upon indigenous knowledge. These include public participatory GIS (PPGIS) (Brown & Kyttä, 2014), in-depth interviews, document research (Raymond et al., 2010; Scholte et al., 2015), the contingent value method (Baral et al., 2008), choice experiments (Zander & Straton, 2010), the Delphi method (Nahuelhual et al., 2013), hedonic models and expert-based scoring (La Rosa et al., 2016), among others.

Local perspectives that diverge from the scientific goals of policymakers are often the thorniest issues in conservation programs in protected areas that embrace indigenous knowledge and cultural services (Díaz et al., 2018; Infield, 2001). Current value assessments neither cover all categories nor guarantee a reasonable trade-off. Yet, as CES continually evolve, they have emerged as the service most intricately linked to human and ecosystem interactions. Even with the ambiguous classification and evaluation of CES, the overall trade-offs, including bundled trade-offs, can provide an important foundation for decision-makers (Raudsepphearne et al., 2010). Allocating a dedicated space for local knowledge and culture in future conservation and planning endeavours is essential to foster collaborative conservation efforts (Díaz et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020). Participatory data and knowledge co-generation are especially important when making targeted assessments based on local context and scale (Pandeya et al., 2016).

Located in Yunnan, China, Xishuangbanna is a world-recognised Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot. It safeguards China's largest and most well-preserved tropical forest ecosystem, representing the nation's continental tropical biodiversity. Simultaneously, it is home to nearly 200 Asian elephants Elephas maximus (Zhang et al., 2015). Xishuangbanna is an autonomous prefecture predominantly inhabited by the Dai people but is also home to 12 other ethnic groups. These include the Han, Hani, Lahu, Bulang, Yi, Jinuo, Yao, Wa, Hui, Bai, Jingpo and Zhuang. These diverse communities reside within the Xishuangbanna National Reserve and surrounding areas. The traditional culture of ethnic minorities often includes rich conservation concepts (Liu et al., 2002; Infield et al., 2017; Verschuuren & Furuta, 2016) that have existed since long before modern conservation practices. The indigenous culture of local communities embodies significant CES value and these communities form an integral part of the ecosystem. CES often stand out as a commonly managed and highlighted aspect of many successful conservation programs (Pleasant et al., 2014). However, given their distinct nature compared to other services, CES have not gained traction among local conservationists and decision-makers in Xishuangbanna (Zhang et al., 2020). Thus, this study was designed to investigate the capacity of Xishuangbanna's nature reserves to provide and protect CES.

In this study, we conducted an integrated assessment of CES within two nature reserves in Xishuangbanna. The objective was to identify key types of CES and elucidate their relationships with both local inhabitants and the environment, drawing insights from village-level interviews at a local scale. Although these areas play a pivotal role in biodiversity conservation, little is known about how local communities perceive and associate these areas with CES beyond their function as recreational spaces. The assessment included the following three parts: (1) Identification and description of the types of CES offered by the nature reserves, including their definitions and associated activities; (2) Examination of the spatial distribution of different types of CES and their relationships with environmental variables; and (3) Analysis of how the nature reserves safeguard CES, coupled with future CES management strategies to prioritise conservation.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study site

Xishuangbanna is located in the southern part of Yunnan Province, China, at 21°09′–22°36′N latitude and 99°58′–101.50′E longitude. It is characterised by a western tropical monsoon climate, marked by distinct wet and dry seasons, ample warmth and favourable climatic conditions. These factors contribute to the region's significant productivity potential, fostering a rich diversity of biological resources and resulting in China's most expansive tropical forest vegetation.

Established in 1958, the Xishuangbanna Nature Reserve stands as one of China's earliest protected areas and serves as a typical tropical forest reserve. Spanning an area of 2425 km2, it comprises five subreserves, including the Shangyong and Mengla subreserves, which border Laos and were chosen as focal points of this study. The Shangyong Reserve is located in the south of Mengla County, with an area of 311.84 km2. The terrain is lower in the east and north and higher in the south and southwest. The main types of vegetation are tropical rainforests, mixed broad bamboo forests, evergreen broad-leaved forests, alpine meadows, shrubs and so forth (Lin et al., 2008). The Mengla Reserve lies to the south of the Shangyong Reserve; its topography features a central lowland flanked by elevated areas on both sides, resulting in large altitude variations. The total area of the reserve is 926.83 km2. The main types of vegetation are tropical rainforests, subtropical green broad-leaved forests and monsoon forests (Lin et al., 2014).

Xishuangbanna is an ethnically diverse area inhabited by 13 distinct ethnic groups distributed in the reserve and its surrounding areas, including the Dai, Han, Jinuo, Tibetan, Yao, Hani and Jingpo groups. Over the last six decades, factors like population growth, economic markets and land policies have drastically altered the local agricultural landscape. Natural forests have been largely converted to rubber plantations, and there has been a marked increase in tea cultivation. The explosive growth of rubber cultivation has negatively impacted biodiversity, with the destruction of natural forests leading to the fragmentation of wildlife habitats (Liu et al., 2017). Cultural services have also changed due to economic development and social modernisation. For example, traditional conservation concepts have been abandoned by young people, affecting not only cultural inheritance but also the protection of local ecosystems and biodiversity (Infield et al., 2017). Therefore, an integrated assessment of CES is imperative for the conservation and management of tropical nature reserves from both cultural and ecological value perspectives.

Xishuangbanna is one of the most biologically and culturally diverse areas in China (Verschuuren et al., 2010). Numerous studies have documented the positive influence of indigenous culture in Xishuangbanna, such as sacred sites, in promoting biodiversity conservation (Corlett, 2018; Liu et al., 2002; Liu et al., 1992; Verschuuren & Furuta, 2016; Verschuuren et al., 2010). Evidence shows that despite their smaller size, these sacred sites possess biodiversity levels comparable to those of government-established nature reserves (Verschuuren et al., 2010). However, a research gap exists regarding the indigenous cultures and CES in Xishuangbanna, and decision-making in the management of nature reserves has largely overlooked CES.

2.2 Data collection

We modified the Guidance for the Rapid Assessment of Cultural Ecosystem Services (GRACE) (Infield et al., 2015) for data collection. There are three management zones in the Shangyong sub-reserve and five in the Mengla subreserve. Detailed information about the village interview is provided in SI (Supporting Information: SM.1). The interview was comprised of three sections: background information, CES information and the main threats to the reserve. The second section included the introduction to the survey, the description of the CES, and the importance score for each CES under current and alternative scenarios (see Supporting Information: SM.2). The questionnaire design was based on the TESSA toolkit (Peh et al., 2017). Two scenarios were described to the interviewees: the first depicted the current situation with the protection of the nature reserve in place, while the second described a situation without the protection of the reserve. For comparison, the alternative state that was proposed would primarily meet the villagers' cultivation and development needs. In this scenario, the area would no longer belong to a national nature reserve but instead belong to a more leniently protected area with reduced conservation effort and funding. A detailed description of the alternative state can be found in Liu et al. (2019).

Data on rivers, towns, settlement points and roads were obtained from digitised maps produced by the Yunnan Institute of Forest Inventory and Planning. The digital elevation model was downloaded from the Computer Network Information Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Website: http://www.gscloud.cn). The vegetation map of the study area was generated by the Yunnan Institute of Forest Inventory and Planning by interpreting the SPOT-5 satellite remote sensing images from 2018. A 1:50,000 hydrographic network map and a digital elevation model were utilised as reference control images, and panoramic images were corrected for geometric biases using the ERDAS 9.2 software. The root mean square error was less than 1, indicating that the vegetation map met the precision requirements of the study. The vegetation in the study area was divided into 16 categories: tropical and monsoon forest, broad leaf forest, bamboo, coniferous forest, shrub rangeland, farmland, fruit garden, rubber plantation, tea plantation, other plantation, eucalyptus, water body, road, built-up development, bare land and unused land.

2.3 Data analysis

2.3.1 Summary of the general CES

Each type of CES perceived by local people was recorded in a database that included detailed activities, periods, sites, participants and key words. Participatory mapping was applied to the two distribution maps for the current and alternative states.

2.3.2 Modelling for CES distributions

Social Values for Ecosystem Services (SolVES 3.0) was integrated with maximum entropy modelling software (MaxEnt) to generate complete social value maps and offer robust statistical models (Sherrouse & Semmens, 2015). These describe the relationship between value indices and explanatory environmental variables. This tool provides an improved public domain resource for decision-makers and researchers, enabling a thorough evaluation of the social values tied to ecosystem services. It also facilitates discussions amongst diverse stakeholders on the trade-offs in ecosystem services. The processing is presented in the Supporting Information Materials (SM.3).

2.3.3 Conservation priority for CES

The following three spatial analyses were performed to determine the spatial distribution relationships: Getis-Ord General G, spatial autocorrelation (Moran's I) and average nearest neighbour. Hotspot analysis was used to obtain the distribution pattern of each CES type, while the environmental variables were analysed to predict their impact on the SolVES modelling distributions. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was conducted to explore the difference in importance scores between the two states, initially judging the impact of protected areas on different types of CES.

Combining the impact index and the frequency of cultural service types, that is, the perceived frequency, the cultural service conservation priority index (PI) was defined as the impact of protected areas on each type of cultural service (Ii) multiplied by the perceived frequency of that cultural service. A larger PI indicates that the type of cultural service is affected by the protected area and should receive greater priority in local planning and management. Since the investigation phase in the Mengyuan zone was the wording adjustment phase, the score data for this zone were excluded to avoid result bias.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Description and characteristics of CES

A total of 147 valid questionnaires were obtained from village interviews, which covered all management zones in the study area. The responses represented 52 natural villages and farm production teams, the two predominant village types within the nature reserve. A total of 150 CES points were obtained from the participatory mapping. The ratio of male to female respondents was approximately 68:32, indigenous people accounted for 73% of the respondents and people aged 31 to 50 accounted for 71% of the respondents. The main ethnic groups among the respondents were Hani (37%), Yao (22%), Dai (17%) and Han (11%). The ethnic groups in the minority were Yi, Zhuang, Lahu, Bai and Bulang.

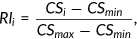

Through the trial interviews in Mengyuan, the following eight types of CES were determined: spiritual and religious, folk and custom, aesthetic and inspirational, educational, cultural heritage, sense of place and identity, leisure and recreational and wildlife. Definitions and descriptions of these types of CES facilitated the interviewees' understanding during the subsequent interview process in the whole study area. The CES types are shown in Table 1. The frequency of mentions for a particular CES type was used to determine perception frequency (Figure 1a). The main types of CES perceived by local residents were wildlife (78.23%), leisure and recreational (73.47%), folk and custom (57.14%) and sense of place and identity (54.42%).

| CES type | Definition and description | Place | Activities/species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual and religious | Landscape with religious or spiritual significance in the region or a place or landscape that brings a sense of sacredness, awe and worship. | Temples, altars, sacred trees, holy hills (Long hills in native languages) | Feast of sacrifice for blessing |

| Folk and custom | Local residents hold activities related to customs in accordance with traditions, related to ethnic groups and beliefs. | Temples, cemetery hills | Open-door festival, closed-door festival, water splashing festival, burial of the dead |

| Aesthetic and inspirational | Nature inspires poetry, design, music, architecture, etc., and people discover the enjoyment or aesthetic value of beauty from sight, scenery, smell, sound, etc. in a certain area. | Valleys, caves in mountains | Relaxation and inspirational activities |

| Educational | Teaching life and work experience and sustainable management through direct and indirect sharing of nature-related experiences and intergenerational knowledge exchange. | Mountains, rubber plantations | Learning and identification of plants, animals and cash crops |

| Cultural heritage | Historically important landscapes, places, or species are valued to connect people to their ancestors, practices and beliefs and to evoke memories. | Ancient temple ruins, ancient trees, karst caves | Sacrifice-related activities |

| Sense of place and identity | People feel a sense of belonging from natural features or activities and a deep connection to the natural environment. | Farmland and rivers beside villages | Collective labour, fishing and collecting medicinal herbs |

| Leisure and recreational | Nature provides local people with opportunities for recreational activities, through which people can relax, socialise and participate in sports and exercise. | Riverside, forests, scenic spots | Fishing, picnic, swimming |

| Wildlife | Animal and plant resources with specific significance are abundant in the place, and the importance of protecting species for future generations is considered. | Forests, nature reserves | Elephants, peacocks, muntjacs, wild boars |

- Abbreviation: CES, cultural ecosystem services.

We digitised and superimposed the 150 points of CES locations obtained during the village interviews to present the overall distribution of cultural service value (Figure 1). The CES points were distributed within the protected area or adjacent to the protected area. In addition, the CES types categorised as recreational, folk and custom and spiritual and religious exhibited a more expansive distribution across the study area. The distribution and score of cultural service value in the unprotected state was notably lower than in the protected state. Although the value of wildlife was frequently perceived, assigning a specific location was difficult; therefore, fewer wildlife points were observed on the distribution map. Under the alternative state, there was a significant decrease in scores pertaining to leisure and recreational value. Additionally, some scores for the CES types such as wildlife, aesthetic and inspirational and sense of place and identity were almost entirely absent. However, the scores for the CES types related to spiritual and religious, as well as folk and custom, remained almost unchanged.

In the current value assessment, CES points were randomly distributed. Conversely, in the alternative state value, the CES points and the changes between the current and alternative states showed a clustered distribution. This indicated that some CES areas were more significantly affected by the disappearance of protected areas (Supporting Information: Table S3).

3.2 Relationship between CES and environmental variables

The type of CES, leisure and recreational, earned the most points (N-COUNT) and the highest maximum value index (M-VI), followed by aesthetic and inspirational, folk and custom and spiritual and religious in the interviews Table S4. Similar to wildlife, it was difficult to define specific locations for the educational and sense of place and identity CES types; thus, these earned lower points. The majority of the CES types were in a relatively clustered distribution (R < 1).

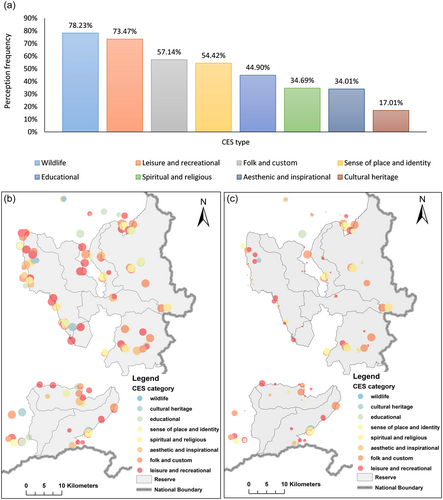

The leisure and recreational, aesthetic and inspirational, folk and custom, spiritual and religious, sense of place and identity, and educational CES types were selected to build a value mapping model, as these had higher points and indices. The predicted distribution of the six CES types is shown in Figure 2a–f, while the main environmental variables affecting their distribution are presented in Table 2. The detailed impact of each variable is available in the Supporting Information: Figures S2–S7.

| Environmental variable | Description | Leisure and recreational | Folk and custom | Spiritual and religious | Aesthetic and inspirational | Sense of place and identity | Educational |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspect | Aspect | 3.2 | 4.7 | ||||

| Cashfore_dist | Distance to cash forest | 14.8 | |||||

| DTR | Distance to road | 35.5* | 10.9 | ||||

| DTW | Distance to water | 33.2* | 6.7 | 8.8 | 4.6 | 22.4 | |

| ELEV | Elevation | 12.5 | 7.3 | ||||

| Farm_dist | Distance to farmland | 21.7 | 37.1* | 20.8 | 64.3* | ||

| Forest_dist | Distance to natural forest | 0.9 | 15 | 2.5 | 11.5 | 53.3* | |

| forest_ fst150 | Frequency of forest within 150 m | 6 | 2.9 | ||||

| LULC | Land use/land cover | 3.9 | 2.3 | 18.3 | 23.4 | 3.4 | |

| Slope | Slope | 8.3 | 17.6 | ||||

| Village_dist | Distance to village | 9.8 | 12.1 | 31.1* | 25.1 | ||

| Village_kernd1 | Density of village | 15.7 | 12.4 | 2.6 | 13.3 |

- Note: ‘*’ represents the highest proportion of environmental variables that influence CES.

- Abbreviation: CES, cultural ecosystem services.

Among the six types of CES analysed, natural education had a training AUC value of 0.742, while the other types had training AUC values above 0.893 (Supporting Information: Table S5), indicating the consistency of the model with the study area. The degree of matching was high, and the results of the cultural value distribution exhibited significant reliability and reference value (Elith et al., 2010; Swets, 1988).

The leisure and recreational values were perceived in the scenic mountains, forests and rivers around the villages according to village interviews (Table 1). Consequently, the distribution of leisure and recreational value was related to water, farmland and cash forest, with the distance-to-water (DTW) variable having the greatest impact (Supporting Information: Figure S2). There was a direct relationship between the closeness of people to water and the perceived value of leisure and recreational activities. A similar relationship was observed for the distance to farmland and cash forest.

The distributions of the folk and custom type and the spiritual and religious type were closely related to the locations of the farmland and villages (Table 1). There was a decrease in values as the distance increased (Supporting Information: Figure S3 and S4). The environmental variable of land use type exerted an impact on the distribution of the spiritual and religious types such as tropical monsoon forests, broad-leaved forests, rubber plantations, farmland or roads (Supporting Information: Figure S3). A fluctuation in the value was observed for the folk and custom types. The value increased as the distance from the natural forest increased, reaching a peak at 200 m, after which it decreased. The rise in elevation was another environmental factor whose increase caused the value of the folk and custom type to decrease (Supporting Information: Figure S4).

The aesthetic and inspirational type value was distributed mainly in tropical rain forests, broad-leaved forests, bamboo forests and other areas with beautiful scenery and quiet environments. VI decreased as distances to forests and roads increased. The VI increased with rising slopes, stabilising within a certain range when the slope reached approximately 23° (Supporting Information: Figure S5).

The sense of place and identity type distribution was related to the location of forests, and respondants mainly perceived it in farmland, rivers and forests near villages. According to Supporting Information: Figure S6, the distribution is concentrated within 50 m of the forest and is affected by the distances to the village and the road. The farther the distance, the lower the value. The distribution around the farmlands was significant for the educational type value, and as the distance to water increased, the value decreased (Supporting Information: Figure S7).

Value transfer mapping models for the leisure and recreational and folk and custom types were selected to predict the whole distribution in Mengla County. The models fitted the data well, with the testing AUC of 0.714 and 0.831, respectively, indicating potentially useful performance to transfer social values to a larger area, that is, the whole of Mengla County (Sherrouse & Semmens, 2015). Distribution characteristics were consistent with the results in the study area (Figure 2g,h). The leisure and recreational service was related to the distance to water, farmland, villages and forests. The distribution of the type of folk and custom was found to be affected by the location of the farmlands and villages and the elevation.

3.3 Impact of nature reserves on CES and conservation priority

The results revealed that the average importance scores of all CES in the alternative state were lower than those in the current state (Table 3). Specifically, the importance scores for the types of spiritual and religious, folk and custom, aesthetic and inspirational and sense of place and identity in the current state were very high (above 4.5). The types of leisure and recreational CES and wildlife CES showed the lowest scores of 3.96 and 3.43, respectively. Comparing the scores between the current state and the alternative state revealed that all CES, except the spiritual and religious type and cultural heritage type, showed significantly higher importance under the protected state than under the nonprotected state.

| CES type | N | Mean importance in current state | Standard error | Mean importance in alternative state | Standard error | p (two-tailed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual and religious | 18 | 4.50 | 0.202 | 4.39 | 0.231 | 0.157 |

| Folk and custom | 45 | 4.60 | 0.140 | 4.24 | 0.204 | 0.027* |

| Cultural heritage | 4 | 4.00 | 1.000 | 3.00 | 1.155 | 0.317 |

| Aesthetic and inspirational | 24 | 4.71 | 0.127 | 2.19 | 0.277 | 0.000** |

| Sense of place and identity | 55 | 4.58 | 0.092 | 2.65 | 0.193 | 0.000** |

| Leisure and recreational | 72 | 3.96 | 0.130 | 3.25 | 0.166 | 0.000** |

| Wildlife | 80 | 3.43 | 0.169 | 2.64 | 0.181 | 0.002** |

| Educational | 49 | 4.37 | 0.126 | 2.35 | 0.213 | 0.000** |

- Abbreviation: CES, cultural ecosystem services.

- * p < .05;

- ** p < .01.

The impact of the two subreserve areas is illustrated in Supporting Information: Figure S8. The types of spiritual and religious CES, folk and custom and cultural heritage had lower impact indices, indicating less impact from the nature reserve. Meanwhile, the other CES types had larger impact indices. The leisure and recreational and wildlife types showed different impact indices in the Mengla and Shangyong reserves, with those for Mengla significantly higher than those for Shangyong (paired t-test, p < .05).

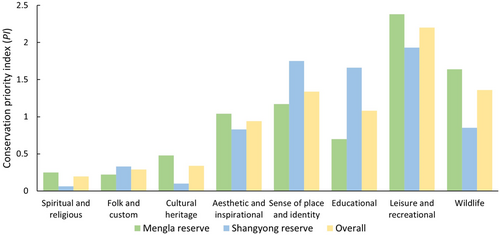

The conservation PI values of various types of CES are shown in Figure 3. Conservation priorities for spiritual and religious, folk and custom and cultural heritage types of CES were the lowest (PI < 1.0), and those for the aesthetic and inspirational type were relatively low. The conservation PI of the sense of place and identity, educational, leisure and recreational and wildlife types was relatively high (PI > 1.0).

Using a five-point Likert scale, we gauged residents' attitudes toward the management practices of these nature reserves (Supporting Information: Figure S9). Residents were relatively supportive (4–5) of the protection and management of landscapes, heritage and species. The results also indicated the relatively positive attitude of local residents (3–4) toward farmland, economic income, community activity spaces and educational resources related to livelihood. Residents' attitudes towards entertainment venues and tourism industries were relatively negative (2–3) because they were unable to enjoy the cultural benefits of nature reserves due to restricted entry. Moreover, the majority of respondents expressed opposition to the restrictions placed on local residents' access to the protected area. They also indicated that current management practices limit the access of local stakeholders to entertainment and leisure venues.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Distributions of CES

The leisure and recreational CES type received the maximum points in this study. The most important influencing factor was the distance from water because the specific recreational activities that local residents frequently mention are fishing in the river, picnics and so forth. Talking to others after farm work is another recreational activity that indicates the distance to farmland as an influencing variable.

The folk and custom type and the spiritual and religious type are important for the residents of Xishuangbanna due to the multiethnic characteristics of this area (Corlett, 2018; Liu et al., 2002; Liu et al., 1992; Zeng & Reuse, 2016). Many sites in Xishuangbanna that are used for spiritual and religious CES and folk and custom CES vary according to different ethnic groups. Therefore, these two types of CES are mostly related to villages and nearby farmlands, mountains and forests where residents live. The interview results indicate that most of the sites that fall under these two types of CES are actually natural sacred sites (e.g., holy hills and cemetery hills) (Liu et al., 2002; Luo et al., 2001; Verschuuren et al., 2010) protected by local residents. Further studies on religious beliefs and ethnic conventions will aid in the identification of these sacred sites and the understanding of their role in biodiversity and ecosystem conservation (Infield, 2001; Infield et al., 2017).

Wildlife is the most frequently mentioned CES type, but it was not analysed in the SolVES model because the locals could not indicate precise locations, resulting in a lack of points. However, the locals exhibited strong awareness and recognition of the importance of wildlife protection for future generations (Supporting Information: Figure S9). This offers a conducive avenue to prioritise wildlife protection and highlight affected areas so that residents can better understand and participate in biodiversity conservation.

4.2 Prioritisation of CES conservation

The most frequently mentioned CES types are wildlife, leisure and recreational, folk and custom and sense of place and identity. The PI indicated a higher conservation priority for leisure and recreational, wildlife, sense of place and identity, and educational CES types, as these are prone to degradation without protection measures. To garner local support, reserve managers should prioritise these types of CES in their policy considerations (Infield, 2001).

Spiritual and religious, folk and custom and cultural heritage CES are very important to local residents (with an importance score >4 in the current state), which is consistent with the study area being an ethnic minority region. The related locations are mainly cemetery hills and holy hills. In general, local residents are highly aware of the religious significance and preservation of these natural sacred sites. Nonetheless, certain villages revealed that their revered hillsides have been destroyed and replaced with cash forests, driven by the quest for local economic development. Hence, it is necessary to strengthen local ethnic beliefs to protect natural sacred sites from degradation through the promotion and documentation of local religious and folk activities and cultural education.

Conservation PI values for both the spiritual and religious, and folk and custom types, are notably low, indicating that the presence of nature reserves does not significantly alter the perception of residents regarding these CES. In a real conservation initiative, leveraging such indigenous conservation practices can reduce protection expenses and expand the scope of the conservation network. In their early research, Liu et al. (1992) indicated that the sacred sites in Xishuangbanna play an important role in the preservation of dry monsoon forests. Vernacular conservation is based on traditional resource management, cultural taboos and township regulations and conventions. By integrating these indigenous protective practices, specifically the protection of sacred sites, into China's protected area system, conservation outcomes can be enhanced with a more efficient allocation of resources and efforts.

Thus, incorporating conservation priorities grounded in CES offers a novel and effective application, especially in China's proposed Asian Elephant National Park, which is currently being developed (Kang & Li, 2022; Yang et al., 2021). For effective planning and development of the national park system, it's imperative to prioritise leisure and recreational, wildlife, sense of place and identity, and educational CES types due to their heightened vulnerability. Conversely, CES types such as spiritual and religious, folk and custom and cultural heritage may be more sustainably overseen through organic local conservation initiatives.

Although the reduction in economic income and available farmland caused by conservation management affects local support, access to recreational value remains the most influential factor in endorsing nature reserves. Many residents expressed that restrictions on entering the reserve limited their ability to freely enter the forest and invite relatives and friends to engage in entertainment and leisure activities. Therefore, the diminished leisure and recreational value of the villages outweighed the loss of economic income. To address this problem, reserve managers should conduct a comprehensive assessment of the advantages and disadvantages, reconsider and adjust access rights for local people, and strengthen the management of community engagement activities. With the consent of the local people, a moderate payment mechanism for ecosystem services can be introduced, granting them access at a low price. Indeed, This approach will give locals more options without imposing excessive fees solely to profit from the protected areas. Furthermore, a comanagement mechanism could be introduced, permitting local people to enter as volunteers. This approach could be adopted as a part of daily patrol or nature education activities, allowing local residents to enjoy entertainment and leisure activities while contributing to the reserve's management.

4.3 Study limitations

First, our study only mapped the distribution of individual service types, given the limitations of the SolVES model being unable to integrate all services in a comprehensive service distribution graph. Second, there was a lack of comparability among different services. Therefore, we recommend the incorporation of an overall CES distribution analysis into future models.

In terms of importance assignment, we did not determine whether it should be assigned a zero value or ignored if a CES type was not mentioned by the respondent. If these null values are ignored, more attention should be paid to the perception of each participant; if these are assigned a zero value for averaging, the result is reflective of the overall population. The survey sample in each village was small; therefore, it may not reflect the perceived importance at the village level and in the surrounding areas. For this reason, we focused only on perceived importance at the individual level. Furthermore, there are chances of errors in the perceptions of the respondents due to the random sampling method. Hence, deriving important indicators for the entire village population based solely on individual perceptions is a hasty approach. Another problem is the potential trade-off in the perceived importance when viewed at an individual level versus a collective population perspective.

In subsequent studies, an intensive and comprehensive survey across a specified area should be conducted to determine whether variations in sampling densities have an impact on the overall distribution of CES values. An additional factor to take into account is whether the results from individual interviews should be used directly as input or whether the results for entire villages should be aggregated and averaged before running the model. In this study, we conducted a relatively intensive survey of the Mengyuan management zone (49 interviews in Mengyuan villages vs. a total of 147 interviews) and discerned that except for two services (i.e., folk and custom CES and spiritual and religious CES), the locations of all the other services varied. A large number of scattered CES points introduced complexities and ambiguities to the analytical process.

4.4 Moving forward for CES involvement in nature conservation

In the context of globalisation, it is necessary to prioritise collaborative research in biodiversity and cultural diversity, harnessing cultural diversity as a tool to protect biodiversity. Areas with high biodiversity are often inhabited by ethnic minorities, and cultural diversity is highly important (Pretty et al., 2009). One-third of the world's land and more than 40% of protected areas are owned and managed by traditional indigenous people (Inouye, 2014). Most nature reserves and rural areas in China have multifunctional landscapes where nature and culture integrate, but a corresponding biological and cultural diversity protection management system is lacking. Beyond policy frameworks and government-led initiatives, attention should be paid to the influential role of local culture, including village regulations and traditional ecological knowledge, to promote coordinated protection of regional biodiversity and cultural diversity, leading to sustainable community development (Bi et al., 2020).

In southeast and southwest China, informal rules and traditional customs govern many forested areas, such as sacred mountains (Shen et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2005), community forests (Gao et al., 2018), and Fengshui forests (Hu et al., 2011). Gao et al. (2018) suggested that government agencies incorporate culturally protected forests into policy and legislative frameworks and introduce ecological compensation mechanisms. However, Allendorf et al. (2014) indicated that strategies for directly integrating these areas into conservation strategies may be inappropriate, as people primarily view these sacred forests as religious sites and do not associate them with ecological value.

For a holistic approach to ecosystem services management, it is imperative to incorporate CES methodically. Many kinds of initiatives, including spatial planning, ecosystem-based management, integrated conservation-development schemes and payment for ecosystem services, stand to gain from a structured consideration of CES. However, despite their significance, many CES are overlooked in ecosystem services research, resulting in their limited incorporation in decision-making processes (Chan, Guerry, et al., 2012).

Integrating CES into the planning and management of nature conservation is not an easy task. An approach based on cultural and religious values tends to be more sustainable compared to those based on legislation or regulation (Liu et al., 2002). However, the deployment of local and informal regulations faces challenges due to globalisation and state-led economic modernisation. This is evident from the decrease in community-level customs and cultural practices as socioeconomic development progresses (Gao et al., 2018; Infield et al., 2017). In some cases, even though the small size of the CES sites might lead to minimal ecological value for local residents, these sites can serve as platforms to enhance understanding of the environment and to highlight the importance of protected areas for biodiversity (Allendorf et al., 2014). Our study contributes to the existing body of knowledge by paving the way to promote CES in nature conservation.

In conclusion, CES should be taken into consideration in our nature conservation strategies. Our study, based in two government-established tropical nature reserves in Xishuangbanna, SW China, identifies eight distinct types of CES. Notably, leisure and recreational and wildlife CES, both with high PI, rely on the formal protection of nature reserves. Conversely, spiritual and religious CES, and folk and custom CES, with lower PI, were protected primarily by community-based conservation. Leveraging and incorporating this vernacular conservation in our existing protected area system can reduce protection costs and extend the conservation network. Simultaneously, maintaining and enriching the cultural well-being of local residents through the safeguarding of vulnerable CES will help gain more local support.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Peng Liu: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; resources; software; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Wenwen Li: Investigation; methodology; software; writing—review and editing. Qiuping Li: Data curation; investigation; resources. Xianming Guo: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; resources. Bin Wang: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; project administration. Ludan Zhang: Data curation; investigation; methodology. Qingzhong Shen: Formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration. Ranfei Fu: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; software. Junyu Peng: Data curation; investigation; methodology. Zhiyun Deng: Data curation; investigation; project administration; software. Li Zhang: Conceptualization; resources; supervision; writing—review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We equally appreciate the field support provided by the Xishuangbanna National Nature Reserve, Mengla Management Station, and Shangyong Management Station. We are also grateful for the assistance of the tour guides of the scenic area Meng yuan PARADISE. We thank Lanxin Wang, Lifan Wang, Hongyu Chen, Yangdong Lin, Shengqiang Liu, Hailong Xu, Xin Dong, Zhong Dong and so forth, for their valuable data and suggestions. We appreciate the participation of the summer practice team from the College of Life Sciences, Beijing Normal University, in the field survey. We are grateful for the financial support of the National Nature Science Foundation of China (31801986) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2018M631372). We also thank the MOE Key Laboratory for Biodiversity Science and Ecological Engineering for their funding.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.