The evolutionary advantages of chelonians are making them vulnerable to extinction in the Anthropocene

龟类的演化优势反使其在人类世容易灭绝

Abstract

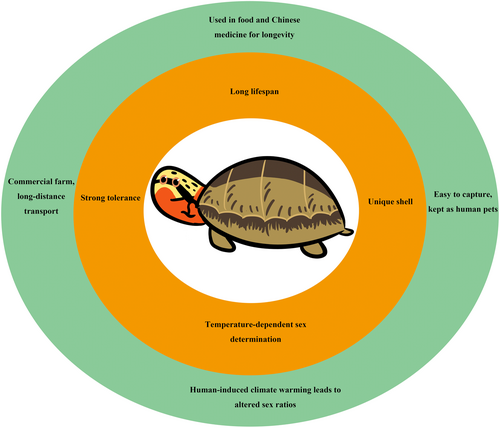

enChelonians have survived for more than 200 million years. The distinct form of the chelonian shell stands as a testament to their enduring success, having survived millions of years of natural selection pressures. Unfortunately, traits and strategies that once ensured their survival—including their shell, strong environmental tolerance, long lifespan, and temperature-dependent sex determination—are turning into disadvantages, particularly in the Anthropocene. This article outlines how this evolutionary success story is now on the brink of an extinction crisis.

摘要

zh龟类已在地球上生存了2亿多年,其外壳经受住了漫长的自然选择的考验。但不幸的是,特异的外壳、坚韧的环境忍耐力、长寿,以及倚赖于温度的性别决定,这些曾使得它们存活下来的性状和策略,在人类世却变成了它们的劣势。本文分析了这些演化优势反促使龟类易于灭绝的原因。【审校:卜荣平】

Practitioner points

en

-

Conservation research should be adapted to changes in species.

-

Conservation science requires special attention to particularly endangered taxa.

-

Conservation researchers should focus on the actual needs of conservation, grasp the front-line status of species protection, and provide timely policy recommendations to promote the improvement of conservation work.

实践者要点

zh

-

保护研究须结合物种的演变。

-

保护科学须重点研究濒危类群。

-

保护科学家须着眼于保护的实际需求,掌握物种保护的最新状态,并及时提供政策建议,改进保护工作。

Wildlife, a critically important component of ecosystems, plays a vital role in maintaining the ecological balance crucial for its own survival as well as that of human beings. Currently, due to excessive human development, habitat destruction and degradation, and overexploitation of wildlife, many species have declined rapidly, are now critically endangered, or have already become extinct (Scheffers et al., 2019). The global impact of human activity is now so substantial that it represents one of the most prominent drivers of vertebrate extinction globally (Maxwell et al., 2016).

Chelonians—turtles and tortoises—have high economic, cultural and ornamental value, and are heavily exploited for food, pets, and traditional Chinese medicine, making them highly targeted for harvesting and trade. More than 800,000 individual Chelonians are traded globally each year (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species Wild Fauna and Flora, 2018). Chelonians' populations are highly susceptible to hunting, and human impacts are endangering many chelonian species, even driving them into extinction. As such, turtles and tortoises are presently the second-most threatened large vertebrate group (exceeded only by primates) (Stanford et al., 2020).

The world's more than 360 living chelonian species and 482 total taxa (species and subspecies) represent an evolutionary success story (Stanford et al., 2020). In fact, chelonians have survived for more than 200 million years, since the Triassic Era, long before most dinosaurs walked the Earth. Unfortunately, some of these evolutionarily successful traits and strategies, such as having a shell, strong environmental tolerance adaptability, long lifespan and fecundity, and temperature-dependent sex determination, are turning into relative disadvantages, particularly in the Anthropocene (Figure 1).

The remarkable shelled body armor of chelonians ensures that they survive under long-term natural selection pressures. The shell is a good anti-predation adaptation, which may be one of the key reasons for turtles' longevity on Earth. However, the shells may limit their locomotion, especially for terrestrial tortoises, reducing their ability to escape, making them extremely easy to capture. Since 1500 CE, 10 taxa (five species and subspecies) of large-bodied tortoise species were driven into extinction by early prehistoric human hunting and exploitation (Turtle Extinctions Working Group et al., 2015). As the shell is also often highly ornamental, many chelonian species are widely kept as pets.

Chelonians have developed an ability to adjust to extreme environmental conditions (Krivoruchko & Storey, 2015). This allows them to successfully adapt to different environments and natural selection pressures. Many chelonians also appear to be well-adapted to fasting and are able to endure prolonged hunger, allowing them to be sedentary and hide. However, their strong tolerance and adaptability make them easy targets for commercial farming without the need for long periods of domestication, and wild populations are easy to exploit for trade. In addition, this ability allows them to survive long-distance transport, making them targets for trade on a global scale.

The life-history traits (e.g., long lifespan, delayed sexual maturity, long fecundity) of chelonians have adapted to strong natural selection pressures. However, these traits have also left chelonian populations vulnerable to new, and potentially devastating threats posed by human exploitation and development-related pressures. Their long lifespan has led many people to believe that they have longevity genes, and the superstition that “you are what you eat” has led to the belief that eating them will improve longevity. In addition, chelonians have long generation times, requiring a considerable period to mature from juveniles to adults, and they remain reproductively active for a long time (long fecundity). Despite this, many individuals are captured before reaching sexual maturity, often preventing them from reproducing. Moreover, large individuals and older females are usually the main targets of hunting and exploitation for food markets (Schneider et al., 2016). Given that these individuals have the highest reproductive value, their loss leads to an insufficient replenishment of offspring and a significant decline in the population.

The sex ratio of chelonians via temperature-dependent sex determination is key for their survival under the long-term pressure of natural selection. Although turtles have survived previous periods of climate change, the existing rate of change is far more rapid (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2023), and turtles may not be able to adapt quickly enough, due in part to their long generation times. In addition, chelonians have limited vagility and may not be able to keep migratory pace with forecasted climatic changes. Human-induced climate warming may thus lead to altered sex ratios, which may be fatal (Berriozabal-Islas et al., 2020). Considering all factors, chelonians may be the most threatened vertebrate group in the world due to climate change-related factors, including the drying up of water bodies and changes in thermal and rain patterns leading to desertification.

Faced with this dire situation for chelonians, we must first ban commercial harvesting and exploitation of turtle and tortoise populations, which is one of the most direct threats to their survival. The priorities should be to design a fully regulated turtle market, strengthen enforcement of relevant wildlife protection laws and build political will and capacity to increase enforcement and prosecution rates against illegal turtle trade, especially of wild individuals. Second, we need to strengthen ecological studies on wild chelonians to determine their habitat requirements and subsequently mitigate the destruction and degradation of these habitats, including that caused by environmental pollution. In particular, we need to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions, as already pledged by several countries. This would be a lifeline for both turtles and humans. In addition, public education is crucial in heightening awareness about the importance of protection and law enforcement to deter illegal trade. By protecting our shared global turtle diversity, we would also be helping to protect our environment from destruction.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Rongping Bu: Writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Tien Ming Lee: Writing—review and editing. Haitao Shi: Conceptualization; supervision; writing—review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Anders Rhodin, who is the Founder and Director of the Chelonian Research Foundation and Executive Vice Chair of IUCN SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, for his review. This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32170532).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.