The risk of vaginal, vulvar and anal precancer and cancer according to high-risk HPV status in cervical cytology samples

Abstract

High-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) is the cause of virtually all cervical cancers, most vaginal and anal cancers, and some vulvar cancer cases. With HPV testing becoming the primary screening method for cervical cancer, understanding the link between cervical hrHPV infection and the risk of other anogenital cancers is crucial. We assessed the risk of vulvar, vaginal and anal cancer and precancer (VIN2+, VaIN2+ and AIN2+) in a prospective cohort study including 455,349 women who underwent cervical hrHPV testing in Denmark from 2005 to 2020. We employed Cox proportional hazard models, adjusting for age, calendar year and HPV vaccination status, and estimated hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). We used the Aalen Johansen estimator to calculate the absolute risks of VIN2+, VaIN2+ and AIN2+. In total, 15% of the women were hrHPV positive at baseline. A positive cervical hrHPV test was associated with increased incidence of vulvar, vaginal and anal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Five-year risk estimates of VIN2+, VaIN2+ and AIN2+ among hrHPV-positive women (0.45%, 0.14% and 0.12%) were higher than among hrHPV-negative women (0.14%, 0.01% and 0.05%). Particularly high risk was observed among the hrHPV-positive women of the oldest age, with a history of anogenital precancer and those not HPV vaccinated. In conclusion, our study confirms the association between cervical hrHPV infection and non-cervical anogenital precancers and cancers. Currently, no established risk threshold or guidelines for follow-up. As HPV testing becomes the primary method for cervical cancer screening, future data will help define high-risk groups and acceptable risk thresholds.

Graphical Abstract

What's new?

Most high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia cases and cervical cancers are caused by high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) infection. Other anogenital cancers also share an etiological link with hrHPV. Here, the authors investigated associations between persistent cervical hrHPV infection and risk of non-cervical anogenital precancers and cancers. Data show that women who test positive for cervical hrHPV are at increased risk of subsequently developing vulvar, vaginal and anal cancer and precancer. Risk was highest among hrHPV-positive women who were older, who had a history of anogenital precancer and who were not vaccinated against HPV. Further study is needed to identify risk thresholds.

1 INTRODUCTION

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection. Nearly all sexually active individuals will encounter an HPV infection at some point in their life.1 Fortunately, most infections are self-limiting and clear within 1 to 2 years.2 However, an HPV infection can become persistent and lead to precancer or cancer at female anogenital sites, including the cervix, vulva, vagina and anal canal. Virtually all high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and cervical cancers are caused by high-risk HPV (hrHPV) infections.2 The natural history of rarer female anogenital cancers, such as vulvar, vaginal and anal, may be less understood. Furthermore, research on the association between a cervical hrHPV infection and the risk of developing vulvar, vaginal and anal cancer or precancerous lesions in the future is limited. In recent years, HPV testing has increasingly become a crucial part of cervical screening programs around the world. It is already today the primary screening method for cervical cancer in many countries.3 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends HPV testing as the first choice of screening method in their cervical cancer screening and prevention guideline published in 2021.3 With the increasing use of HPV testing in cervical screening programs and the etiological link between hrHPV and vulvar, vaginal and anal neoplasia, more knowledge on the potential utilization of routine data from HPV cervical screening programs for predicting non-cervical anogenital HPV-related diseases is needed.

Studies have shown that women with a history of cervical cancer or CIN2/3 have an increased long-term risk of other female anogenital cancers.4-8 Only one previous study has investigated the association between cervical hrHPV infection and the subsequent risk of vulvar, vaginal and anal cancer and high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia or worse in the vulva (VIN2+), vagina (VaIN2+) and anus (AIN2+),9 however, without having the statistical power to investigate cancer as a separate entity.

In this population-based study, including more than 455,000 women with a cervical hrHPV test result, we aim to evaluate whether a positive cervical hrHPV test is associated with increased risk of vulvar, vaginal and anal precancer or cancer development. Furthermore, we aimed to assess the absolute risk of non-cervical anogenital precancer or worse according to cervical hrHPV status, overall and by age, history of anogenital precancerous lesions and HPV vaccination status.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study population and data sources

The study population comprises all female residents in Denmark who had a cervical hrHPV test in relation to the cervical cancer screening program in 2005 to 2020. Cervical cancer screening in Denmark began gradually in the 1960s and became a more organized screening program in mid 1980s. Since 2007, all female residents aged 23 to 65 received an invitation to a cervical cytological screening every third year for women aged 23 to 49 and every fifth year for women 50 to 65.10 The HPV test was implemented in 2005 as a supplement when atypical squamous cells of undermined significance (ASCUS) were detected on cervical cytology and as an exit test for women having their last cervical screening before turning 65 years of age. In addition, the HPV mRNA test was implemented in some regions in Denmark in 2007 as a triage for women with LSIL. In 2017, a delayed one-time offer exit test, an HPV test, was introduced to all female residents born before 1948 and no longer included in the screening program due to their age. Furthermore, the study population includes women from the pilot implementation study of HPV-based screening (HPV SCREEN DENMARK), which was launched in a part of the Region of Southern Denmark in 2017. From May 2017 to December 2020, 40% of the women aged 30 to 59 who attended routine screening in the area were assigned to HPV-based screening. Although the screening was based only on the HPV results, cytology was available. We identified the study population in the Danish National Pathology Registry, leading to a study population of 455,349 women. Women diagnosed with cervical, vulvar, vaginal or anal cancer before baseline, the first cervical hrHPV test date, were excluded (n = 1930).

2.2 Follow-up and registry-linkage

In Denmark, all residents are assigned a unique personal identification number in The Danish Civil Registry, which contains information on the date of birth and gender. All health and population registers use personal identification numbers universally, allowing accurate linkage between individual-level national records. In our study, we used these unique identification numbers to extract and link data from six registries: the Danish National Pathology Registry,11 The Danish Cancer Register,12 The Danish Civil Registry,13 Statistics Denmark, the National Health Service Registry and the Danish National Prescription Registry.

The Danish National Pathology Registry contains information and results of all cytological and histological examinations in Denmark. The registry is considered complete from 1997 and onwards, but many departments have also included historical data back to 1970.11 Information on cervical HPV tests, CIN2/3, VIN2/3, VaIN2/3 and AIN2/3 diagnosed up until December 31, 2021, was extracted from the Danish National Pathology Registry. The diagnoses are coded using the Danish version of the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine based on topography and morphology codes.11 The HPV type is, to some extent, specified for the cervical HPV test in the pathology register, most notably HPV16. However, many of the tests are just characterized as hrHPV positive with no specific HPV type indicated. The Danish Cancer Registry was used to identify all cervical, vulvar, vaginal and anal cancer cases. The register contains information on diagnoses, morphology and topography of all Denmark cancer cases since 1943.12 We used the 7th and 10th editions of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes to identify anogenital cancers and then the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology 3rd edition to identify squamous cell carcinomas (SCC), which is the histological type associated to hrHPV infection in vulvar, vaginal and anal cancer. For cervical cancer all histological types were included. The version of the Danish Cancer Registry available at the time of analysis contained information until December 31, 2020. Therefore, we identified all cases of cervix, vulvar, vaginal and anal cancer diagnosed in 2021 from the Danish National Pathology Registry by topography and morphology codes. Information on emigration and death was collected from the Danish Civil Registry.13 Data on HPV vaccination status was obtained from the Danish National Prescription Registry and the National Health Service Registry, which contain information on HPV vaccinations administered as part of the national vaccination program.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Women entered the study cohort on the date of their first cervical hrHPV test in 2005 to 2020. To ensure that the cervical hrHPV test was part of routine screening and not a follow-up of previous abnormalities, we defined the baseline as the first hrHPV test with no prior abnormal cervical cytology or histology within the last 18 months. The hrHPV exposure was classified as either hrHPV positive or hrHPV negative. In the analyses on the risk of high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia or worse (IN2+), the women were followed until the diagnosis of the analysis-specific high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (IN2/3) or anogenital cancer, emigration, death or end of follow-up the December 31, 2021, whichever occurred first. And for the analyses on the risk of vulvar, vaginal and anal cancer, the women were followed until the diagnosis of anogenital cancer, emigration, death or the end of follow-up on December 31, 2021.

Cox proportional hazard regression models were initially used to assess a possible association between a cervical hrHPV test and the incidence of vulvar SCC, vaginal SCC and anal SCC, respectively. Associations are presented as estimated hazard ratios with 95% confidence levels (CI) according to hrHPV status at baseline with time since the baseline hrHPV test as the underlying timescale. The models were adjusted for age in four groups (23–44, 45–59, 60–65 and >65 years), calendar year in three groups (2005–2006, 2007–2016 and 2017–2020) and HPV vaccination status (yes, no) all measured at baseline and specified as strata variables allowing the baseline hazard to differ. We further used the model to assess the association between a cervical hrHPV infection and precancer lesions (VIN2+, VaIN2+ and AIN2+).

The Aalen Johansen estimator was used to estimate the absolute risk of vulvar SCC, vaginal SCC, anal SCC, VIN2+, VaIN2+ and AIN2+, respectively, as a function of time since baseline, according to hrHPV status at baseline. Death and anogenital cancer, both squamous cell carcinoma and other types, were regarded as competing events. Furthermore, we assessed the 5-year absolute risk in subgroups according to age, history of anogenital IN2+ and HPV vaccination status respectively. We further performed a sub analysis where we estimated the absolute risk of VIN2+, VaIN2+ and AIN2+ for women with a known HPV16 positive test.

All statistical analyses were conducted using the statistical software SAS 9.4.

3 RESULTS

The study cohort consists of 455,349 women who had a cervical hrHPV test as a part of the cervical cancer screening program in Denmark from 2005 to 2020.

3.1 Characteristics of the study population

Table 1 describes the baseline characteristics of the study population according to cervical HPV status and stratified into four age groups. The median age for the whole study population was 62 years (range 23–100 years). The high age is due to the large portion of women attending the delayed exit screening provided as a one-time offer in 2017 to women born before 1948. Of the 455,349 women, 68,715 (15%) were hrHPV positive at baseline and 9862 were HPV16 positive. The majority (62%) of the hrHPV positive women were 23 to 44 years old with a median age was 40 years (range 23–96 years). ASCUS/LSIL was the most prevalent cytology result seen in the younger groups of women. 69% to 77% of the hrHPV-positive women <60 years had ASCUS/LSIL, compared to 30% to 35% of the hrHPV negative in the same age range. Most women over 60 had normal cytology or no cytology at all. The women's cytology results reflect their entry into the study population. During follow-up, 700 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer, 9536 died and 4042 women emigrated before developing one of the outcomes.

| Characteristics at baseline | hrHPV negative women | hrHPV positive women | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23–44 years | 45–59 years | 60–65 years | >65 years | 23–44 years | 45–59 years | 60–65 years | >65 years | |||||||||

| N = 73,926 | N = 47,992 | N = 136,595 | N = 128,121 | N = 42,737 | N = 10,293 | N = 9215 | N = 6470 | |||||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||||||

| Calendar year | ||||||||||||||||

| 2005–2006 | 481 | 1% | 444 | 1% | 59 | 0% | 36 | 0% | 821 | 2% | 141 | 1% | 25 | 0% | 12 | 0% |

| 2007–2016 | 39,211 | 53% | 22,369 | 47% | 54,628 | 40% | 9050 | 7% | 27,214 | 64% | 5783 | 56% | 3937 | 43% | 848 | 13% |

| 2017–2020 | 34,234 | 46% | 25,179 | 52% | 81,908 | 60% | 119,035 | 93% | 14,702 | 34% | 4369 | 42% | 5253 | 57% | 5610 | 87% |

| hrHPV vaccination status | ||||||||||||||||

| Vaccinated | 17,674 | 24% | 1100 | 2% | 713 | 1% | 225 | 0% | 13,956 | 33% | 349 | 3% | 90 | 1% | 47 | 1% |

| Not vaccinated | 56,252 | 76% | 46,892 | 98% | 135,882 | 99% | 127,896 | 100% | 28,781 | 67% | 9944 | 97% | 9125 | 99% | 6423 | 99% |

| HPV status | ||||||||||||||||

| hrHPV negative | 73,926 | 100% | 47,992 | 100% | 136,595 | 100% | 128,121 | 100% | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| hrHPV positive (any hrHPV type) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 42,737 | 100% | 10,293 | 100% | 9215 | 100% | 6470 | 100% | ||||

| HPV16 positive | NA | NA | NA | NA | 6085 | 14% | 1272 | 12% | 1495 | 16% | 1010 | 16% | ||||

| Type of hrHPV test | ||||||||||||||||

| DNA | 56,664 | 77% | 40,734 | 85% | 135,055 | 99% | 127,589 | 100% | 26,609 | 62% | 8003 | 78% | 8779 | 95% | 6345 | 98% |

| mRNA | 12,453 | 17% | 3881 | 8% | 515 | 0% | 210 | 0% | 11,195 | 26% | 1313 | 13% | 153 | 2% | 37 | 1% |

| Unknown | 4809 | 7% | 3377 | 7% | 1025 | 1% | 322 | 0% | 4933 | 12% | 977 | 9% | 283 | 3% | 88 | 1% |

| Cervical cytology | ||||||||||||||||

| Normal | 22,485 | 30% | 13,534 | 28% | 12,081 | 9% | 8696 | 7% | 5912 | 14% | 1829 | 18% | 4724 | 51% | 3054 | 47% |

| ASCUS/LSIL | 25,769 | 35% | 14,383 | 30% | 1678 | 1% | 915 | 1% | 32,955 | 77% | 7149 | 69% | 1176 | 13% | 612 | 9% |

| ≥HSIL | 360 | 0% | 264 | 1% | 85 | 0% | 148 | 0% | 1745 | 4% | 406 | 4% | 368 | 4% | 283 | 4% |

| Cytology unknown/not performed | 25,312 | 34% | 19,811 | 41% | 122,751 | 90% | 118,362 | 92% | 2125 | 5% | 909 | 9% | 2947 | 32% | 2521 | 39% |

| History of anogenital IN2+ | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 14,152 | 19% | 5143 | 11% | 7029 | 5% | 3598 | 3% | 5546 | 13% | 1593 | 15% | 904 | 10% | 500 | 8% |

| No | 59,774 | 81% | 42,849 | 89% | 129,566 | 95% | 124,523 | 97% | 37,191 | 87% | 8700 | 85% | 8311 | 90% | 5970 | 92% |

3.2 Association between cervical hrHPV and non-cervical anogenital cancer and precancer

3.2.1 Vulva

A total of 851 women developed VIN2+ during follow-up. VIN2/3 was the most severe diagnosis for 695 women (82%), and 156 (18%) developed vulvar SCC. A positive cervical hrHPV test was associated with an increased hazard of vulvar SCC and VIN2+ (Table 2) when adjusting for age, calendar year and HPV vaccination status at baseline (vulvar SCC: HR 3.7 [95% CI: 2.5–5.4]; VIN2+: HR 4.4 [95% CI: 3.8–5.1]).

| Outcome | Cervical hrHPV status | No. of women at baseline | Person-years of follow-up | No. of events | Adjusted HRa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 455,349 | HR | (95% CI) | ||||

| Vulvar | ||||||

| Vulvar SCC | hrHPV negative | 386.634 | 1.861.547 | 113 | 1 | (ref) |

| hrHPV positive | 68.715 | 412.061 | 43 | 3.7 | (2.5–5.4) | |

| VIN2+ | hrHPV negative | 386.634 | 1.860.022 | 515 | 1 | (ref) |

| hrHPV positive | 68.715 | 410.859 | 336 | 4.4 | (3.8–5.1) | |

| Vaginal | ||||||

| Vaginal SCC | hrHPV negative | 386.634 | 1.861.547 | 7 | 1 | (ref) |

| hrHPV positive | 68.715 | 412.061 | 12 | 19.9 | (7.5–52.9) | |

| VaIN2+ | hrHPV negative | 386.634 | 1.861.397 | 50 | 1 | (ref) |

| hrHPV positive | 68.715 | 411.672 | 99 | 16.5 | (11.5–23.8) | |

| Anal | ||||||

| Anal SCC | hrHPV negative | 386.634 | 1.861.547 | 110 | 1 | (ref) |

| hrHPV positive | 68.715 | 412.061 | 26 | 2.2 | (1.4–3.4) | |

| AIN2+ | hrHPV negative | 386.634 | 1.861.171 | 215 | 1 | (ref) |

| hrHPV positive | 68.715 | 411.777 | 92 | 2.9 | (2.2–3.8) | |

- a Adjusted for age, calendar year and HPV vaccination status at baseline.

3.2.2 Vaginal

Of the 455,349 women in our study population, 149 were diagnosed with VaIN2+ during follow-up. Of these, 19 (13%) had a vaginal SCC, and 130 (87%) had VaIN2/3 as their worst diagnosis. We found that a positive cervical HPV test was associated with an increased hazard for developing vaginal SCC and VaIN2+ (Table 2). After adjusting for age, calendar year and HPV vaccination status at baseline, the hazard ratio was 19.9 (95% CI: 7.5–52.9) for vaginal SCC and 16.5 (95% CI: 11.5–23.8) for VaIN2+.

3.2.3 Anal

Altogether, 307 women were diagnosed with AIN2+ during the follow-up period. Of these, 136 (44%) had anal SCC as their most severe diagnosis, and 171 (56%) had AIN2/3.

The adjusted hazard ratio was increased for anal SCC and AIN2+ for hrHPV-positive women when compared to women testing HPV negative (anal SCC: HR 2.2 [95% CI: 1.4–3.4]; AIN2+: HR 2.9 [95% CI: 2.2–3.8]) (Table 2).

3.3 Absolut risk of non-cervical anogenital high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer

3.3.1 Vulva

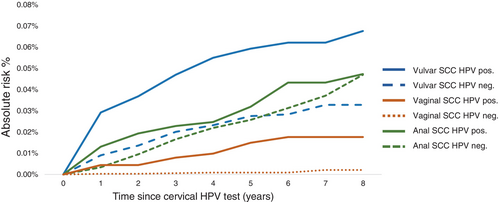

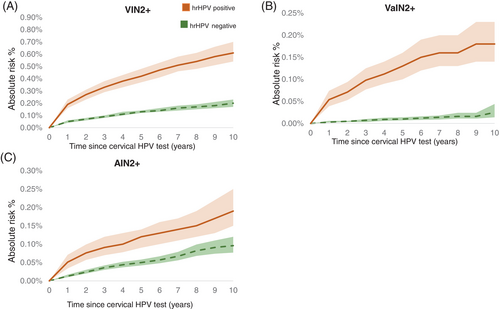

During follow-up, women testing positive for cervical hrHPV at baseline had a higher absolute risk of vulvar SCC than HPV-negative women (Figure 1), and the same pattern was observed for VIN2+ (Figure 2A). The 5-year overall absolute risk of VIN2+ among hrHPV-positive women was 0.45% (95% CI: 0.40–0.51); but varied according to age, history of IN2+ and HPV-vaccination status. The risk increased with age and the estimated level was 1.32% (95% CI: 0.93–1.82%) among hrHPV positive women age >65. (Table 3). A previous diagnosis of anogenital IN2+ was associated with elevated VIN2+ risk (Table 3). Among hrHPV positive women with previous anogenital IN2+ the estimated 5-year risk was 1.54 (95% CI: 1.28–1.83). Among not HPV-vaccinated hrHPV positive women the estimated 5-year absolute risk was 0.51% (95% CI: 0.45–0.57) (Table 3).

| Baseline characteristics | N | VIN2+ | VaIN2+ | AIN2+ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hrHPV negative | hrHPV positive | hrHPV negative | hrHPV positive | hrHPV negative | hrHPV positive | ||||||||

| 5 year | 5 year | 5 year | 5 year | 5 year | 5 year | ||||||||

| % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | ||

| Overall | 455,349 | 0.14 | (0.13–0.15) | 0.45 | (0.40–0.51) | 0.01 | (0.008–0.016) | 0.14 | (0.11–0.17) | 0.05 | (0.05–0.06) | 0.12 | (0.09–0.15) |

| Age | |||||||||||||

| 23–44 | 116,663 | 0.12 | (0.09–0.15) | 0.25 | (0.20–0.31) | 0.003 | (0.000–0.012) | 0.05 | (0.03–0.08) | 0.03 | (0.02–0.05) | 0.08 | (0.05–0.11) |

| 45–59 | 58,285 | 0.17 | (0.13–0.22) | 0.60 | (0.46–0.78) | 0.015 | (0.006–0.032) | 0.26 | (0.17–0.38) | 0.07 | (0.04–0.10) | 0.18 | (0.11–0.29) |

| 60–65 | 145,810 | 0.13 | (0.11–0.15) | 0.80 | (0.62–1.03) | 0.009 | (0.005–0.016) | 0.19 | (0.11–0.31) | 0.06 | (0.04–0.07) | 0.20 | (0.12–0.32) |

| >65 | 134,591 | 0.17 | (0.13–0.21) | 1.32 | (0.93–1.82) | 0.025 | (0.010–0.057) | 0.57 | (0.29–1.04) | 0.06 | (0.04–0.07) | 0.18 | (0.10–0.32) |

| History of anogenital IN2+ | |||||||||||||

| No | 416,884 | 0.10 | (0.09–0.11) | 0.29 | (0.25–0.34) | 0.011 | (0.007–0.021) | 0.10 | (0.08–0.14) | 0.04 | (0.04–0.05) | 0.09 | (0.07–0.12) |

| Yes | 38,465 | 0.59 | (0.50–0.70) | 1.54 | (1.28–1.83) | 0.021 | (0.009–0.045) | 0.38 | (0.26–0.53) | 0.19 | (0.14–0.25) | 0.33 | (0.22–0.48) |

| HPV-vaccination status | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 34,154 | 0.15 | (0.10–0.23) | 0.23 | (0.16–0.33) | 0 | 0 | 0.07 | (0.04–0.13) | 0.05 | (0.02–0.10) | 0.08 | (0.04–0.15) |

| No | 421,195 | 0.14 | (0.13–0.15) | 0.51 | (0.45–0.57) | 0.01 | (0.009–0.016) | 0.16 | (0.12–0.19) | 0.05 | (0.05–0.06) | 0.13 | (0.10–0.17) |

3.3.2 Vaginal

The limited number of vaginal SCC is reflected in the low-risk estimates among hrHPV-positive and hrHPV-negative women (Figure 1). The absolute risk of VaIN2+ was greater in women who tested positive for hrHPV at baseline than in HPV negative women (Figure 2B). The estimated 5-year risk of VaIN2+ among hrHPV positive women was 0.01% and increased with age, reaching 0.57% (95% CI: 0.29%–1.04%) among women aged >65. A previous diagnosis of anogenital IN2+ was linked to a higher probability of VaIN2+ (Table 3). The estimated 5-year absolute risk of VaIN2+ among hrHPV positive women with prior anogenital IN2+ was 0.38 (95% CI: 0.26–0.53). Unvaccinated compared to vaccinated, hrHPV positive women had a greater absolute risk of VaIN2+, the 5-year risk estimate for unvaccinated hrHPV positive was 0.16% (95% CI: 0.12–0.19) (Table 3).

3.3.3 Anal

The absolute risk of anal SCC was slightly higher in hrHPV positive than negative women during the follow-up period reaching the same risk level of 0.05% at 8 years of follow-up (Figure 1) However, the absolute risk of AIN2+ was higher in hrHPV positive than negative women (Figure 2C). The 5-year risk among hrHPV positive women was 0.12% (95% CI: 0.09–0.15) and increased slightly with age (Table 3). Previous anogenital IN2+ diagnosis was associated with increased AIN2+ risk; the 5-year risk estimate was 0.33 (95% CI: 0.22–0.48) among hrHPV positive women with previous anogenital IN2+. We observed a slightly lower 5-year risk of developing AIN2+ among HPV vaccinated than unvaccinated hrHPV positive women (Table 3).

We also examined the absolute risks among women testing HPV16 positive on the cervix. At baseline, 9862 women were HPV16 positive; the majority were between the ages of 23 and 44, had no history of previous anogenital IN2+, and had not received HPV vaccination (Table 4). We found markedly higher absolute risks of VIN2+, VaIN2+ and AIN2+ than those observed among all hrHPV positive women. Again, the oldest age groups, women with past anogenital IN2+, and non-vaccinated women had the greatest 5-year risk estimates.

| N | VIN2+ | VaIN2+ | AIN2+ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 year | 5 year | 5 year | |||||

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | ||

| HPV16 positive | 9862 | 1.35 | 1.12–1.61 | 0.29 | 0.19–0.42 | 0.26 | 0.17–0.38 |

| Age | |||||||

| 23–44 | 6085 | 0.54 | 0.38–0.77 | 0.06 | 0.02–0.17 | 0.11 | 0.05–0.24 |

| 45–59 | 1272 | 1.67 | 1.03–2.58 | 0.31 | 0.11–0.77 | 0.42 | 0.16–0.93 |

| 60–65 | 1495 | 3.37 | 2.41–4.58 | 0.65 | 0.30–1.26 | 0.60 | 0.30–1.11 |

| >65 | 1010 | 3.87 | 2.42–5.84 | 1.82 | 0.62–4.27 | 0.40 | 0.14–1.00 |

| History of anogenital IN2+ | |||||||

| No | 8492 | 0.83 | 0.64–1.06 | 0.20 | 0.12–0.33 | 0.20 | 0.12–0.32 |

| Yes | 1370 | 4.56 | 3.50–5.82 | 0.81 | 0.41–1.46 | 0.62 | 0.23–1.20 |

| HPV-vaccination status | |||||||

| Yes | 1671 | 1.09 | 0.66–1.71 | 0.12 | 0.03–0.43 | 0.14 | 0.03–0.51 |

| No | 8191 | 1.40 | 1.15–1.70 | 0.32 | 0.21–0.48 | 0.28 | 0.18–0.42 |

4 DISCUSSION

In this nationwide population-based cohort study including more than 450,000 women with a cervical hrHPV result, we showed that cervical hrHPV infection is associated with vulvar, vaginal and anal cancer and precancer. Women with a positive cervical hrHPV test were at increased risk of subsequently developing vulvar, vaginal and anal cancer and precancer compared to those testing hrHPV negative. Additionally, we observed that advanced age, a previous history of anogenital IN2+ and the lack of HPV vaccination were factors contributing to the identification of high-risk subgroups within hrHPV-positive women This was especially apparent when looking at HPV16-positive women.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association between a positive cervical hrHPV test and the risk of vulvar, vaginal and anal cancer. A previous study conducted in Denmark by Bertoli et al9 found, in agreement with our findings, that a positive cervical hrHPV test was associated with a higher risk of VIN2+, VaIN2+ and AIN2+ than a negative hrHPV test and that the greatest increased risk was associated with a HPV16 infection. Nonetheless, their study lacked the statistical power to independently assess the association with cancer.9 Some other studies have investigated the risk of anogenital cancers after a CIN2/3 diagnosis, with CIN2/3 serving as a proxy for persistent cervical hrHPV infection. In line with our results, they found a CIN2/3 diagnosis to be associated with an elevated risk of developing non-cervical anogenital cancer.4, 5, 7, 14

A few plausible mechanisms could potentially explain the increased risk of non-cervical anogenital precancerous lesions and cancers in women testing positive for cervical hrHPV. First, co-infections in anogenital sites are frequent, making it more likely for a woman to also harbor HPV in her vagina, vulva or anal canal if she has the virus at the cervix.15 Also, women with cervical HPV infection may be more likely than HPV-negative women to acquire a new HPV infection at other anogenital sites, either due to different sexual behavior patterns or increased susceptibility to new infections.16 Finally, women who tested positive for a cervical hrHPV infection may have lower ability to clear an HPV infection at other mucocutaneous junction zones.17

With hrHPV testing becoming the primary method of cervical cancer screening, the information gained from the screening program may be used to identify women at increased risk of other rarer HPV-related cancers. A positive cervical hrHPV test, according to our data, is related with an increased absolute risk of VIN2+, VaIN2+ and AIN2+, particularly in specific subgroups. Although the absolute risk of vulvar, vaginal and anal cancer after a single positive cervical hrHPV test is generally low, clinical follow-up may be warranted, particularly for high-risk groups such as those with HPV16 infection,9, 15 women with previous anogenital precancerous lesions,7, 14 individuals without HPV vaccination and immunocompromised women such as organ transplant recipients and those living with HIV.18

The strengths of this nationwide cohort study are the prospective study design, the large study population and the long follow-up with virtually no loss to follow-up. We essentially included all women with a cervical hrHPV test and detected all cases of VIN2+, VaIN2+ and AIN2+ diagnosed in Denmark during the study period. This is possible due to the existence of the unique personal identification number assigned to all Danish citizens and the existence of high-quality nationwide registries in Denmark. This makes it possible to correctly link individual-level data from the different national registries. A further strength of our study was that we were able to adjust for HPV vaccination status at baseline.

Our study also has some limitations. We cannot exclude that our results are influenced by surveillance bias. Women who have a positive cervical hrHPV test are referred to a colposcopy where other anogenital lesions which are most of without symptoms, most likely particularly vulvar and vaginal lesions, are more prone to be detected, which potentially can lead to surveillance bias. This is especially the case since Denmark has no vulvar, vaginal or anal cancer screening program. Given that the group of hrHPV-positive women in the study population had a median age of 40, it is possible that some of these women had not yet developed pre- or invasive cancer. Another limitation is the selection bias of the younger women, aged 23 to 59 years, where the majority had an HPV test following an ASCUS/LSIL diagnosis on a routine screening. This may have led to an overestimation of the absolute risk in younger women. HPV testing first became a primary screening method for this age group in 2021 in Denmark. Finally, the HPV type was not specified for all the hrHPV-positive women.

In conclusion, our results support the important association between cervical hrHPV infection and non-cervical anogenital cancer. Women with a cervical hrHPV infection have an elevated absolute risk of VIN2+, VaIN2+ and AIN2+. Despite this noteworthy association, there is currently no established risk threshold, and due to the rarity of the diseases, there are no guidelines at the moment for further follow-up of women at increased risk. However, as HPV testing gains importance as a cervical cancer screening tool, more comprehensive data will be accessible, enabling the identification of high-risk groups and the definition of an acceptable risk threshold.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Sofie Lindquist: Design of the study and the analyses; conducted the literature review, performed the statistical analyses with support from Kirsten Fredriksen and wrote the first draft of the article; reviewed the article critically for important intellectual content and approved the final article for submission. Kirsten Frederiksen: Design of the study and the analyses; reviewed the article critically for important intellectual content and approved the final article for submission. Lone Kjeld Petersen: Reviewed the article critically for important intellectual content and approved the final article for submission. Susanne K. Kjær: Design of the study and the analyses; funding; reviewed the article critically for important intellectual content and approved the final article for submission. The work reported in the article has been performed by the authors, unless clearly specified in the text.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The study was funded by the Mermaid II project and the Danish Cancer Society's grant Combat Cancer.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Susanne K. Kjær has received research grants unrelated to our study through her institution from Merck. Lone Kjeld Petersen has received speaker fee from Merck. The remaining authors declared no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study was approved by the Danish National Board of Health Data (FSEID-00004345), Statistics Denmark (J.nr. 707,596) and registered in the archive list of the Danish Cancer Society Research Center (J.nr. 2019-DCRC-0050). According to Danish law, no approval from the Ethical Committee is required for this register-based study.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Statistics Denmark provides the data that support the study's findings. Data is available upon request from Statistics Denmark if the necessary rights are sought and secured. Further information is available from the corresponding author upon request.