Who gets mad, sad, scared or happy at discipline? Emotion attributions explain child externalizing behaviour

A preliminary version of this study was presented as a poster at the 2022 Annual Convention of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, San Francisco, California, United States.

Funding information: Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo

Abstract

Few studies have linked parental discipline with children's emotional experiences, and not much data explore children's emotional attributions to discipline linked to externalizing behaviour. With a sample from Brazil, this study examines which emotions children most aptly attribute to a protagonist facing spanking, time-out or inductive discipline for norm violations. We hypothesized that anger, sadness, and fear would have higher attribution rates at spanking or time-out, relative to inductive discipline and that happiness would have higher attribution rates at induction relative to the other discipline modalities. We expected these findings to be more pronounced in older children. Based on emotional functions, we also tested the role of neutrality and happiness attributions to discipline in children's externalizing behaviour. A two-way MANOVA, with discipline and child age as explanatory variables, showed that children attributed more anger at time-out or spanking than at induction, and more happiness and neutrality at induction than at either time-out or spanking. Older children attributed significantly more sadness and less fear or neutrality. Hierarchical regressions showed that child externalizing behaviour was negatively related to happy attributions in discipline independently of child emotion situation knowledge or demographics. The results are interpreted in light of a functional view of emotions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Both common sense and empirical data (Alvarenga et al., 2011; Perlman et al., 2008; Robinson & Cartwright-Hatton, 2008) suggest that children, as well as parents, experience increased distress in the context of discipline, in which parents attempt to control child behaviour. Yet, not all modalities of discipline may elicit in children the same discrete emotions. For example, earlier Freudian research linked aversive emotions of fear, anxiety and anger to physical and over-reactive punishment (Robinson & Cartwright-Hatton, 2008; Turiel, 2006). However, some studies report that discipline strategies involving induction by means of explanations of social rules or cultivation of empathy toward others are linked to less distress in parents and children, and hence more effectively foster children's moral development (Arsenio & Ramos-Marcuse, 2014; Hoffman, 2000; Lansford, 2019). In a recent path analysis, Yavuz et al. (2022) reported that inductive discipline was indirectly related to child prosocial behaviours through higher child sympathy, which suggests that the child's emotion understanding plays a key role in the link between parental discipline and child prosocial behaviour.

As they age, children rely less on expressive cues and more on situational cues to interpret others' emotions (Gnepp, 1983; Reichenbach & Masters, 1983). In addition, with age, children may better comprehend that discipline encompasses more than just corporal punishment. For example, toddlers expect the corporal third-party punishment of an individual who refuses to defend a social partner following aggression (Geraci & Surian, 2021). As they age, however, children may associate sadness or anger with parental spanking and sympathy toward others with the parental explanation that one's action has caused distress in others (Yavuz et al., 2022), thus reacting differently to varying forms of discipline (Lansford, 2019). Furthermore, parents who keep their composure (e.g., higher vagal tone) in the context of discipline and model more appropriate emotional responses are more likely to engage in effective emotion socialization practices (Perlman et al., 2008), which may also make their discipline more effective (Lansford, 2019).

In a literature review, Lansford (2019) suggests that the emotional climate in parent–child interactions depends, in part, on whether the child is embracing or resisting the parent's short-term (e.g., getting the child into bed) and long-term goals (e.g., promotion of moral principles). When a child's goals and behaviours are consistent with those of the parent, emotions in the parent–child interactions tend to be more positive. However, when a child's goals and behaviours diverge from those of the parent, the parent may respond with cooperative, non-restrictive strategies (e.g., reasoning, negotiating), empathic strategies (e.g., validating the child's wish or perspective), or power-assertive strategies (e.g., imposing the parent's own will through physical force; Lansford, 2019). In general, children are more likely to resist forceful strategies as they do not take children's preferences and perspectives into account (Lansford, 2019). Therefore, the use of force may undermine the emotional climate in the parent–child interactions and the parents' future attempts to gain the children's compliance. Unfortunately, not many studies have explored the link between parental various discipline modalities and children's emotional reactions, and not much data exist on how children's different emotion attributions at discipline may relate to their externalizing behaviour such as aggression and delinquent acts independently from their emotion knowledge.

This study seeks to fill this gap by addressing two important questions specifically in the context of two large Brazilian cities, which are under-represented in the literature. First, which emotions (happy, angry, sad, scared) do children most aptly attribute to a protagonist facing parental spanking, time-out or inductive discipline for norm violations? How about neutral attributions? It was hypothesized that anger, sadness and fear would have higher attribution rates at spanking or time-out, relative to inductive discipline. We assume that feelings of anger, fear, and sadness are more strongly linked to forms of discipline that restrict the child's freedom (i.e., time-out) or inflict pain (i.e., spanking) than inductive discipline, which is instructive and corrective but non-punitive in nature (Lansford, 2019). By contrast, it was predicted that the use of disciplinary induction would be linked to higher happiness attribution than the use of spanking or time-out as forms of parental discipline, since happiness is functionally conducive to learning (Izard, 1991), the goal of induction. We also explored whether neutral attribution varied by discipline and predicted that the differential emotion attributions by discipline would be stronger in older children. That is, we expected children's age to be a moderator in the relationship between discipline and emotion attributions. This prediction is based on evidence that parents are more likely to use spanking with preschoolers than with school-aged children (Choe et al., 2013), and that as parents increasingly diversify their approaches to discipline with older children, children also increase their attention to situational cues in emotion attributions (Reichenbach & Masters, 1983). Consequently, older children can be deemed more likely than their younger counterparts to modulate their emotional reactions depending on how restrictive or empowering the parent's chosen mode of discipline is (Lansford, 2019).

The second question to be addressed in this study concerns the link between emotion attributions at discipline in general and maternal rates of child externalizing behaviour. Much data (Trentacosta et al., 2008) supports the link between lower SES, paternal absence, and being male as demographic risk factors in child behaviour problems. Some data (Coie & Dodge, 1998; Miner & Clarke-Stewart, 2008) also suggest that children exhibit less externalizing behaviour with age, although early data from the Child Behaviour Checklist showed no significant age effect on externalizing scores (Achenbach, 1978). Another point to consider is that, despite some opposing evidence (Izard et al., 2001), prior US studies also suggest that children's externalizing behaviours such as observed or teacher-reported aggression (Denham et al., 2002; Fine et al., 2004; Schultz et al., 2000) are linked to either ‘bias’ or ‘inaccuracy’ in anger attribution. However, these studies rely mainly on the ‘identification of emotions unequivocally appropriate to certain situations’ (Denham et al., 2002, p. 904, emphasis added), reflecting children's emotion situation knowledge (ESK; Denham et al., 2015).

Child discipline, however, is not a prototypical situation in which any specific emotion can be easily chosen as ‘most appropriate’ cross-culturally (Alvarenga et al., 2011), as pointed out by Kägitçibasi (2007) when discussing cultural variations in the reaction of children from different countries to parents' restrictive versus non-restrictive discipline. In social contexts where parental restrictive control tends to be combined with a high level of parental warmth (e.g., some minority groups within the US, some Asian societies), the meaning and importance given to parental restrictive control may not be as negative as that associated with authoritarian parenting in Anglo-Saxonic contexts (Akcinar & Baydar, 2014; Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997; Kägitçibasi, 1996). In cultures where physical punishment is normative and perceived by children and parents as appropriate, it is likely administered in a controlled manner in the context of a nurturing relationship and may not be positively associated with externalizing behaviour problems as reported with predominantly Anglo-Saxonic samples (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997). How this reflects on the parent–child emotional climate during discipline in those cultures is not clear in the literature, though. In an earlier study with another sample (Alvarenga et al., 2011), Brazilian children were found to most likely attribute sadness to a protagonist being disciplined. In the present study, we try to replicate this finding in addition to testing for other emotions such as anger, fear, and happiness linked to various discipline modalities.

Externalizing behaviour in childhood has often been associated with antisocial behaviour patterns in adolescence and adulthood (Kazdin, 1995). Because researchers have identified early onset as less common but more severe and resistant to change than adolescent-onset (Kazdin, 1995; Moffitt, 1993), it is important to study externalizing behaviour in the school years that precede puberty—that is, ages 5 to 10. Prevention efforts need to concentrate in those formative years when parental discipline is paramount and before the influence of peers grows significantly stronger (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2002, 2011).

From a functionalist approach (Frijda, 1994; Izard, 1991), emotions signal the significance of events to concerns. To the extent that discipline means getting ‘in trouble’ for misbehaviour, presumably children with externalizing behaviour tendencies are less likely to attribute happiness, which is an emotion linked to personal satisfaction and affiliation (cf. Izard, 1991), to a protagonist facing parental disciplinary action for norm violation. Rather, apathy or emotional neutrality in the context of discipline may serve the adaptive goal of disengaging from the consequences of social transgression. Therefore, in this study, we predict that greater neutrality and lower happiness in discipline relate to children's higher externalizing behaviour rates.

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

The study protocol was approved by Plataforma Brasil. Participants were recruited through their schools, and their mothers signed an informed consent form. Children got symbolic tokens of appreciation (e.g., pencils, stickers) for their participation. Seventy-six children (55.3% boys) between 5 and 10 years of age (mean age = 7 years, 1 month; SD = 1.56) with no known diagnosis in two large cities in Brazil participated in this study. Fifty-eight mothers (76.3%) reported being married, 7.9% (n = 6) reported being divorced, and 14.5% (n = 11) either omitted marital status information or marked ‘Other’. Sixty mothers (78.9%) had a college education or higher. Sixty children (78.9%) were reported to live with their biological father.

2.2 Measures

Mothers provided demographic information by completing a brief form including income, educational level, family size, presence of the child's biological father at home (0 = No; 1 = Yes), and child gender (0 = male, 1 = female) and age. They also completed a paper-and-pencil checklist of child behaviours. The child measures were administered in random order by research assistants to each child individually at their school.

2.2.1 Emotion attributions

To measure emotion attributions, 36 vignettes with two parts were read to each child: Part 1—A protagonist commits a specific transgression (e.g., moral—stealing, hurting a peer, breaking their mother's favourite vase; or social-conventional—wearing clothes with the inside out, stepping out of line in school, making noise in class). Part 2—the protagonist's mother finds out and applies the discipline. For each part, the child was asked to say and point to the photo in response to the question: ‘Do you think Joe/Mary felt happy, sad, angry, scared or didn't feel anything?’ (Experimenter models verbal labelling and pointing to the photo for each emotional state). The photos were a set of validated multicultural, mixed-sex emotional expressions from the Emotion Matching Task (Izard et al., 2003). Part 1 answers served as a frequency measure of emotions attributed to the violation; Part 2 answers served as a frequency measure of emotions attributed to discipline. Only Part 2 of the 36 vignettes was used in this study. The total frequency count for each emotional state attributed to the protagonist (Happiness, Sadness, Anger, Fear, No emotion) was used.

The maternal discipline varied and rotated among three modalities: (1) Spanking (e.g., ‘When Luke's/Lucy's mom found out she spanked Luke/Lucy’), (2) Time-out (e.g., ‘When Luke's/Lucy's mom found out, she sent Luke/Lucy to his/her bedroom’), and (3) Inductive Reasoning (e.g., ‘When Luke's/Lucy's mom found out, she explained to Luke/Lucy that the other kid now was going to be cold with no jacket to wear in the freezing winter’).

2.2.2 Externalizing behaviour

A validated Portuguese version (Bordin et al., 1995) of the Child Behaviour Checklist (4–18; Achenbach, 1991) was used to measure children's externalizing behaviour. In this widely used instrument, parents use a 3-point scale (0 = untrue of the child, or behaviour absent; 2 = very true of the child, or behaviour frequently present) to inform the frequency of aggressive (e.g., ‘Argues a lot’, ‘Gets in fights’) and delinquent behaviours (e.g., ‘Lies, cheats’) in their children. Cronbach's α for this sample was 0.86, which is good.

2.2.3 Emotion situation knowledge

Part 2 of the Emotion Matching Task (EMT; Izard et al., 2003; Morgan et al., 2009) was translated into Portuguese by one of the authors and used to index the ESK of participants. Criterion validity of the EMT has been reported (Izard et al., 2008) in connection with an intervention programme to improve the understanding of emotions in US Head Start children. Morgan et al. (2009) reported significant correlations of EMT scores with those on two widely used emotion knowledge tests as evidence for the construct validity of the EMT.

Part 2 of the EMT is called Expression-Situation Matching as it specifically taps expressive emotion situation knowledge; that is, the appropriate matching of specific emotions as causal or consequent to events or behaviours. This skill has been found to emerge at preschool age and continue developing through elementary school (Brody & Harrison, 1987, cited in Morgan et al., 2009). A warm-up item ensures that children accurately link emotion labels to facial expressions using a quartet of colour photographs of ethnically diverse elementary school children's expressions of happiness, sadness, anger and fear. Labelling of these basic emotions is usually mastered at preschool age (Denham, 1998). The 12 items ask the child to point to the photo of a child in each of a series of situations—for example, ‘show me the one who got a pretty puppy for a birthday present’, for which the correct answer is the happy face. Each item is marked as either right or wrong; the total number of correct answers was used in the analyses. Morgan et al. (2009) reported a Kuder–Richardson's α of 0.88 on the entire EMT scale and 0.54 on Part 2 of the instrument, which in the present sample was slightly higher at 0.59.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Pattern of emotion attributions

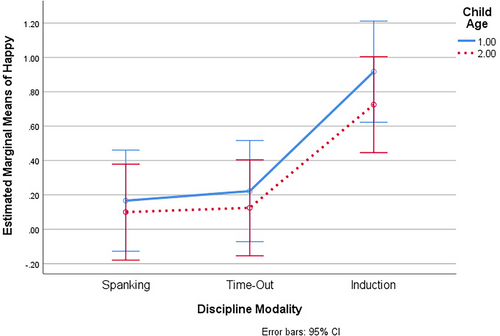

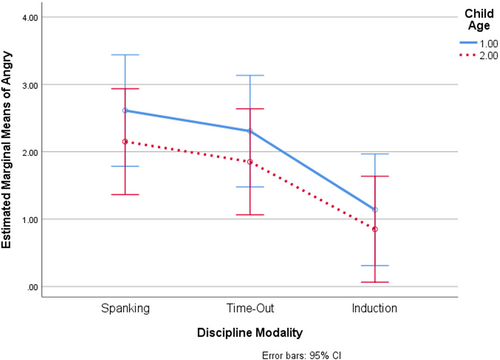

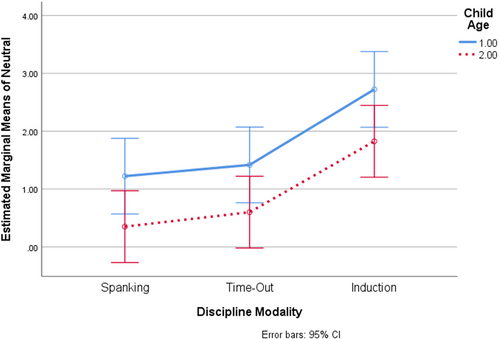

A two-way MANOVAwas used to test the differences between emotion attributions by child age and discipline modality in the vignettes. Wilk's Lambda for Discipline was 7.35, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.14, and Wilk's Lambda for Child Age was 3.88, p = 0.002, partial η2 = 0.08. There was no significant discipline-by-age interaction, contrary to the hypothesis. Table 1 summarizes the distribution of the mean emotion attribution rates by discipline modality and child age. As in Alvarenga et al.'s study (2011), Sadness was by far the emotion most readily attributed by sampled children to the protagonist undergoing discipline. This finding was independent of discipline modality, contrary to predictions. Overall, Happiness was the emotion least frequently attributed to the violator facing discipline. A post hoc Tukey's test showed that when Induction was used, children attributed Anger less often than when either Time-out or Spanking was used, as hypothesized (see Table 1 and Figure 1). However, no significant difference by discipline was found in mean Fear attribution rates. By contrast, as predicted, Inductive discipline elicited significantly higher Happiness attribution rates than either Time-out or Spanking, a differential pattern which was also found for Neutral attributions (see Table 1 and Figures 2 and 3, respectively).

| Emotion attribution | Discipline modality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanking, M (SD) | Time-out, M (SD) | Induction, M (SD) | F | df | part η2 | p | |

| Happy | 0.13 (0.47) | 0.17 (0.44) | 0.82 (1.40) | 14.08 | 2 | 0.11 | 0.000 |

| Angry | 2.37 (3.01) | 2.07 (2.63) | 0.99 (1.72) | 6.33 | 2 | 0.05 | 0.002 |

| Sad | 7.99 (3.61) | 8.00 (3.43) | 7.37 (3.60) | 0.82 | 2 | 0.01 | ns |

| Scared | 0.64 (1.08) | 0.68 (1.29) | 0.51 (1.00) | 0.48 | 2 | 0.00 | ns |

| Neutral | 0.76 (1.68) | 0.99 (1.54) | 2.25 (2.66) | 12.30** | 2 | 0.10 | 0.000 |

| Emotion attribution | Child age | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <6.67, M (SD) | >6.67, M (SD) | F | df | Part η2 | p | |

| Happy | 0.44 (1.00) | 0.32 (0.89) | 1.00 | 1 | 0.00 | ns |

| Angry | 2.02 (2.77) | 1.62 (2.37) | 1.44 | 1 | 0.01 | ns |

| Sad | 6.93 (3.69) | 8.56 (3.24) | 12.54 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.000 |

| Scared | 0.78 (1.32) | 0.47 (0.90) | 4.34 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.038 |

| Neutral | 1.79 (2.53) | 0.93 (1.57) | 10.65 | 1 | 0.10 | 0.000 |

As for age's main effects, older children attributed significantly higher Sadness rates and lower Fear and Neutrality rates than younger children. However, there was no significant attribution rate difference between age groups for Happiness or Anger (see Table 1).

3.2 Explaining externalizing behaviour

A series of hierarchical regression analyses was used to test the hypothesis linking emotion attributions in discipline to child externalizing behaviour in four steps. First, the demographic factors of Family Income per-capita, Paternal Absence, and Child Sex and Age were entered, yielding a significant F value of 4.032, p = 0.005. As shown in Table 2, except for Child Age and Family Income, each one of these factors was significantly related to externalizing behaviour in the predicted direction, and the model accounted for 19% of the variance. Next, ESK was entered into the regression equation in Model 2, which was significant, F(5,71) = 3.322, p = 0.01, but ESK had no significant unique effect, as shown in Table 2.

| Variable | B | SE B | Β | R2 | ΔR2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.005 | |||

| Constant | 22.29 | 4.85 | 0 | |||

| Child age | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.18 | 0.144 | ||

| Gender | −4.18 | 1.5 | −0.31 | 0.007 | ||

| Present father | −5.33 | 1.85 | −0.33 | 0.005 | ||

| Income per-capita | 4.71 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.867 | ||

| Model 2 | 0.2 | 0.007 | 0.448 | |||

| Constant | 19.22 | 6.32 | 3 | |||

| Child age | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.17 | 0.156 | ||

| Gender | −4.25 | 1.51 | −0.31 | 0.006 | ||

| Present father | −5.2 | 1.87 | −0.32 | 0.007 | ||

| Income per-capita | 6.13 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.829 | ||

| ESK | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.448 | ||

| Model 3 | 0.3 | 0.096 | 0.089 | |||

| Constant | 27.88 | 8.03 | 0.001 | |||

| Child age | −0.08 | 0.05 | −0.21 | 0.111 | ||

| Gender | −3.97 | 1.47 | −0.29 | 0.009 | ||

| Present father | −5.3 | 1.84 | −0.33 | 0.005 | ||

| Income per-capita | 1.59 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.956 | ||

| ESK | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.731 | ||

| Joy | −1.2 | 0.5 | −0.31 | 0.02 | ||

| Anger | −0.07 | 0.27 | −0.05 | 0.789 | ||

| Sadness | −0.18 | 0.18 | −0.21 | 0.328 | ||

| Fear | −0.53 | 0.34 | −0.19 | 0.13 | ||

| Model 4 | 0.24 | 0.037 | 0.081 | |||

| Constant | 17.97 | 6.25 | 0.005 | |||

| Child age | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.11 | 0.375 | ||

| Gender | −4.14 | 1.49 | −0.31 | 0.007 | ||

| Present father | −4.92 | 1.85 | −0.3 | 0.01 | ||

| Income per-capita | −4.02 | 0 | −0.02 | 0.888 | ||

| ESK | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.77 | ||

| Neutrality | 0.34 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.081 | ||

- Note: Gender—0 = Male, 1 = Female; present father—0 = Biological father is absent, 1 = biological father is present; income per-capita = Income in Reais divided by the number of people in the household; ESK = Emotion Situation Knowledge as measured by the Emotion Matching Task, Part 2 (Izard et al., 2003).

Each attributed emotion was entered into Model 3, yielding a significant F value of 3.383, p = 0.006. In this model, only Happiness yielded a significant unique effect after controlling for the demographic and ESK effects (see Table 2). The lower the Happiness attribution rates at discipline, the higher the child's Externalizing Behaviour rates, as predicted, β = −0.31, p = 0.02. Finally, given that neutrality conceptually means that emotions are absent, the discrete emotions were excluded in Model 4 and Neutrality was entered. Model 4 was significant, with F(6,71) = 3.383, p = 0.006 and Neutrality showed a marginal positive relation to Externalizing Behaviour, with a β = 0.22, p = 0.08 (see Table 2). Likewise, as shown in Table 2, the increase in R2 between Models 2 and 3, and 2 and 4 was marginal.

4 DISCUSSION

Children's emotion attributions in specific situational contexts are thought to reflect their own prior emotional experiences in analogous situations (Schultz et al., 2001). In this study, we looked at the specific context of parental discipline for moral and conventional transgressions and found that, out of four pre-selected emotions plus Neutrality, Sadness is the one most often attributed to a disciplined protagonist in a vignette regardless of discipline modality, thus corroborating Alvarenga et al.'s earlier report (2011) with another Brazilian sample. In addition, although generally more rarely attributed to a disciplined peer, Anger, Happiness, and Neutrality were found to vary as a function of particular discipline modalities in use.

4.1 Discipline-specific emotion attributions

The data supported the hypothesis that children associate Anger more closely with Spanking or Time-Out than with Inductive discipline. However, contrary to prediction, this finding was independent of child age. Specifically, Anger was attributed more than twice as frequently when the violator protagonist faced Spanking or Time-Out, as compared with Inductive discipline. Conversely, the data also supported the hypothesis that children associate Happiness much more closely with Induction than with either Spanking or Time-Out, with a mean rate difference of more than fourfold. This result was also independent of the child's age. Taken together, these results suggest that, just like with Anglo-Saxonic samples (Lansford, 2019), Brazilian children are less welcoming of power-assertive, restrictive discipline than non-restrictive discipline. Parents all over the world use disciplinary actions with the dual goal of enforcing rules and controlling child behaviour based on cultural norms (Grusec & Davidov, 2007; Kägitçibasi, 2007). However, to a great extent, the emotional state of both parents and children during discipline may play a pivotal role in ensuring that such socialization goals will be achieved. Parents and others working with children (e.g., teachers and therapists) need to consider that the use of discipline strategies that promote anger in children may not be as effective as those that promote happiness. From the evolutionary perspective, the latter is more conducive to adaptive responses of affiliation and mastery than the former (Izard, 1991). This may help explain why Induction more effectively promotes children's moral development than Spanking or Time-Out (Arsenio & Ramos-Marcuse, 2014; Hoffman, 2000).

Although no specific a priori hypothesis was made with respect to the attribution of Neutrality based on discipline modality, the data showed more than double the mean Neutral attribution rates for Induction relative to that for either Spanking or Time-Out. In the specific context of a parent explaining to a norm violator the consequences of their misbehaviour to others, or the rationale for certain social rules, it is easy to imagine why sampled children would readily think that the protagonist would not feel anything. First, contrary to situations of Spanking or Time-Out, the violator receiving Inductive discipline is not ‘in trouble’ for their misbehaviour. So, this is a good reason not to feel anything (i.e., no threat). Second, in being shown the consequence to others for their misbehaviour, the violator is invited to learn a lesson and to reason (Arsenio & Ramos-Marcuse, 2014)—for example, stealing someone else's jacket will deprive the victim of warmth and comfort. A learning situation is more naturally linked to a state of mind marked by self-composure rather than ‘fight-or-flight’ (i.e., anger or fear; see Alvarenga et al., 2011).

4.2 Age differences in emotion attributions

Across discipline modalities, a pattern of age difference in emotion attributions was also found in this study. Specifically, younger children showed higher Neutrality and Fear attribution rates associated with discipline than older children, and older children showed higher Sadness attribution rates linked to discipline than younger children. There was no significant age difference in the attributions of Happiness or Anger.

Parents and other adults involved with child socialization (e.g., therapists, teachers) should respect younger children's tendency to link Fear to discipline in general, and instead capitalize on their higher tendency to associate discipline with Neutrality, as compared to older peers. Instead of using threats to magnify young children's fear, parents should keep their calm and composure during a situation of discipline, thereby making behaviour control and socialization more effective (Lansford, 2019; Perlman et al., 2008). On the other hand, adults should also be mindful that older children are more likely to associate discipline with sadness than their younger peers and therefore, they should channel older children's sorrow into apology and careful consideration of steps for making amends or fixing the adverse consequences of norm violations. Parents, caregivers, teachers and child therapists can promote emotional self-regulation and competence in children through emotional communication, guidance, and particularly ‘causal talk’ in the context of various emotional experiences, including discipline (Housman, 2017).

4.3 Happiness and neutrality in relation to externalizing behaviour

Results also supported the hypothetical pattern of decreased Happiness in discipline linked to higher Externalizing Behaviour, but the hypothesized positive association of Neutrality to Externalizing Behaviour turned out to be only marginal. As in previous studies (Trentacosta et al., 2008), boys and children living without their biological father received significantly higher externalizing behaviour rates than girls or children living with their biological father, but neither family income per-capita nor child age-related to child externalizing behaviour in this sample. Because age difference is more often found in the aggressive type of externalizing behaviour than in the delinquent type (Kazdin, 1995), the present non-significant results are not surprising given that both aggressive and delinquent types were included (see Achenbach, 1978). ESK did not relate to Externalizing Behaviour, either, consistent with some prior data (Izard et al., 2001). This may be due to the low reliability of the ESK measure, even though it was slightly higher than that in the normative sample (Morgan et al., 2009). However, when the discrete emotions were entered into the regression equation, Happiness did have a significant unique effect on Externalizing Behaviour, so for each increase of one standard deviation unit in Externalizing Behaviour, Happiness attributions declined by 31% of one standard deviation, p = 0.02. This finding may be reflective of more aggressive, delinquent children's own limited positive emotional experiences and low attribution rates of positive emotions to others in the context of discipline in general.

Neutral attributions at discipline had but a marginal positive relation with Externalizing Behaviour above and beyond the effects of demographic factors and ESK. Therefore, contrary to prediction, as externalizing behaviour rates rise, children are only marginally increasing their emotional indifference as a coping mechanism in the presence of discipline.

4.4 Limitations and conclusions

The use of a sample from the country of Brazil helps us extend to this cultural group the previous data with US samples (Lansford, 2019) reporting children's preference for non-restrictive to restrictive forms of discipline. However, a limitation of this study is its reliance on quantitative data only. The addition of open-ended questions would have enriched our understanding of the rationale for children's emotion attributions. To this end, future investigations would benefit from combining quantitative and qualitative data (Arsenio & Ramos-Marcuse, 2014). Another limitation of this study is the low internal consistency of the ESK measure used. Nevertheless, the data in this study suggest that in general, Brazilian children associate discipline with the emotion of Sadness, regardless of discipline modality, while also associating Anger more closely with Spanking and Time-Out, and Happiness and Neutrality with Induction. A clear pattern of variance in emotion attributions at discipline by age is also found in this study, with younger children more likely to associate discipline with neutrality and fear, and older children more likely to associate discipline with sadness. Finally, increased rates of externalizing behaviour are associated with a decline in happiness attribution rates, which from a functional view of emotions may explain why children with problem behaviours are less teachable or appreciative of parental discipline.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Ebenézer A. de Oliveira: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Deise M. L. F. Mendes: Conceptualization; data curation; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; writing – review and editing. Luciana F. Pessôa: Conceptualization; data curation; investigation; writing – review and editing. Susana K. de M. Oliveira: Data curation; investigation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We have no conflict of interest to disclose.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study was registered with Plataforma Brasil and the protocol was approved. All participating mothers signed an informed consent form; children verbally assented to be in the study.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data and emotion attribution measure are available for reviewers during the review process upon request to verify the analyses.