Guidance for Design and Endpoints of Clinical Trials in Chronic Hepatitis B—Report From the 2019 EASL-AASLD HBV Treatment Endpoints Conference

Abstract

Representatives from academia, industry, regulatory agencies, and patient groups convened in March 2019 with the primary goal of developing agreement on chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) treatment endpoints to guide clinical trials aiming to “cure” HBV. Agreement among the conference participants was reached on some key points. “Functional” but not sterilising cure is achievable and should be defined as sustained HBsAg loss in addition to undetectable HBV DNA 6 months post-treatment. The primary endpoint of phase III trials should be functional cure; HBsAg loss in ≥30% of patients was suggested as an acceptable rate of response in these trials. Sustained virologic suppression (undetectable serum HBV DNA) without HBsAg loss 6 months after discontinuation of treatment would be an intermediate goal. Demonstrated validity for the prediction of sustained HBsAg loss was considered the most appropriate criterion for the approval of new HBV assays to determine efficacy endpoints. Clinical trials aimed at HBV functional cure should initially focus on patients with HBeAg-positive or negative chronic hepatitis, who are treatment-naïve or virally suppressed on nucleos(t)ide analogues. A hepatitis flare associated with an increase in bilirubin or international normalised ratio should prompt temporary or permanent cessation of an investigational treatment. New treatments must be as safe as existing nucleos(t)ide analogues. The primary endpoint for phase III trials for HDV coinfection should be undetectable serum HDV RNA 6 months after stopping treatment. On treatment HDV RNA suppression associated with normalisation of alanine aminotransferase is considered an intermediate goal. In conclusion, regarding HBV “functional cure”, the primary goal is sustained HBsAg loss with undetectable HBV DNA after completion of treatment and the intermediate goal is sustained undetectable HBV DNA without HBsAg loss after stopping treatment.

Abbreviations

-

- AASLD

-

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

-

- ALT

-

- alanine aminotransferase

-

- anti-HBs

-

- hepatitis B surface antibody

-

- cccDNA

-

- covalently closed circular DNA

-

- CHB

-

- chronic hepatitis B

-

- CpAM

-

- core particle assembly (or allosteric) modulator

-

- DILI

-

- drug-induced liver injury

-

- EASL

-

- European Association for the Study of the Liver

-

- EMA

-

- European Medicines Agency

-

- ETV

-

- entecavir

-

- FDA

-

- Food and Drug Administration

-

- HCC

-

- hepatocellular carcinoma

-

- IFN

-

- interferon

-

- INR

-

- international normalised ratio

-

- LLOD

-

- lower limit of detection; lower limit of quantification

-

- LLOQ

-

- lower limit of quantification

-

- NA

-

- nucleos(t)ide analogues

-

- NAPs

-

- nucleic acid polymers

-

- NTCP

-

- sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide

-

- PEG-IFN

-

- pegylated interferon

-

- pgRNA

-

- pregenomic RNA

-

- RIG-I

-

- retinoic acid-inducible gene I

-

- TDF

-

- TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate

-

- TLR

-

- toll-like receptor

-

- ULN

-

- upper limit of normal

Introduction and Nomenclature for “Cure”

To promote and facilitate the planning and execution of new trials in the field of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) with the ambition of developing a “cure”, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) jointly organised an HBV Treatment Endpoint Conference, a follow-up to a similar conference in 2016.1, 2 Participants, representing patient groups, regulatory agencies (US Food and Drug Administration [FDA] and European Medicines Agency [EMA]), academia and industry assembled in London on March 8-9th 2019.

This report summarises the discussions and opinions of the 2-day meeting with an emphasis on endpoints and design of clinical trials aimed at HBV “cure”. EASL and AASLD selected the meeting organisers and the report represents the view of the participants as reported by the authors and reviewed and approved by the speakers and moderators of the conference.

In the context of the emergence of novel therapies, the main aim of the conference was to develop an agreement on HBV treatment endpoints to guide the design of clinical trials aiming to “cure” chronic HBV infection.

Throughout the meeting, key questions were posed and the participants voted on and discussed the options presented. These questions were further examined during a closed session involving 24 experts (including the 4 authors) representing all the stakeholder groups.

Nomenclature

The most appropriate terminology to describe the goal of chronic HBV treatment was contentious. While the term “cure” offers hope for both researchers and patients, a sterilising cure for HBV is beyond reach in the near term and any implication of cure might be considered as over-reaching. Other less ambitious terms proposed included remission, resolved infection, and sustained virologic response but none was preferred.

For now, the agreement was to keep the term “functional cure”. The majority of participants agreed that “functional HBV cure” should be defined as durable hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) loss (based on assays with lower limit of detection [LLOD] ~0.05 IU/mL) with or without HBsAg seroconversion and undetectable serum HBV DNA after completing a course of treatment (Table 1). It is recognised that in this situation covalently closed circular (ccc) DNA is still present in the liver in very small amounts or in a transcriptionally inactive state, and integrated HBV DNA is still present. Thus, HBV reactivation can occur spontaneously or upon immunosuppression.3 For the patient community, the loss of HBsAg is an important goal because it removes the stigma of HBV infection.

| Sterilising “Cure” | Idealistic Functional “Cure” | Realistic Functional “Cure” | Attainable Partial Functional “Cure” | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical scenario | Never infected | Recovery after acute HBV | Chronic HBV with HBsAg loss | Inactive carrier off treatment |

| HBsAg | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive |

| Anti-HBs | Negative/Positive | Positive | Positive/negative | Negative |

| HBeAg | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Serum HBV DNA | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | Low level or not detected |

| Hepatic cccDNA, transcription | Not detected | Detected | Detected | Detected |

| Not active | Not active | Not active | Low level | |

| Integrated HBV DNA | Not detected | Detected? | Detected | Detected |

| Liver disease | None | None | Inactive, fibrosis regress over time | Inactive |

| Risk of HCC | Not increased | Not increased | Declines with time | Risk lower vs. active hepatitis |

- Abbreviations: Anti-HBs, antibody to HBsAg; cccDNA, covalently closed circular DNA; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Endpoint Definitions for HBV Therapy and Surrogates for HBV Functional Cure

HBsAg Loss as a Surrogate for HBV Functional Cure

Surrogate endpoints of HBV functional cure measure biochemical (normalisation of alanine aminotransferase [ALT]), virological (undetectable HBV DNA, HBsAg loss ± seroconversion, hepatitis B e antigen [HBeAg] loss ± seroconversion), and histological (improvement in inflammation and/or fibrosis) outcomes. Normalisation of ALT is a problematic endpoint due to the lack of a standardised definition of normal ALT,1, 2 and the presence of other common concurrent liver conditions, such as fatty liver, that confound its interpretation.4, 5 The assessment of histological improvement is challenged by the need for liver biopsy, a procedure infrequently performed in clinical practice and a potential barrier to clinical trial enrolment. Sustained suppression of HBV DNA under the LLOD of current assays is associated with improved clinical outcomes.6-10 Of note, current HBV DNA assays usually have a LLOD of <10 IU/mL. Importantly, undetectable HBV DNA plus loss of HBsAg based on current assays with LLOD ~0.05 IU/mL is associated with even better outcomes.11-14

HBsAg loss captures virological and clinical aspects of functional cure, in that it is generally associated with both undetectable HBV DNA in serum and improvement in clinical outcomes.11-14 HBsAg loss is uncommon in nucleos(t)ide analogue (NA)-treated patients, especially in Asian patients and those with HBeAg-negative (vs. HBeAg-positive) active hepatitis B.11, 15, 16 However, when it does occur with current therapies, HBsAg loss is usually durable, associated with sustained HBV DNA suppression and with incremental reduction in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) risk compared to viral suppression without HBsAg loss.79-81, 83

HBsAg loss induced by NA therapy appears to be as durable as that occurring spontaneously or with pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) therapy.11, 17, 18 In a retrospective study of 4,080 patients who lost HBsAg (3,563 spontaneous and 475 after NA treatment), >90% of patients in both groups remained HBsAg negative on follow-up tests although only 38% of patients had detectable hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) at the time of HBsAg loss.18 Studies also suggest that anti-HBs seroconversion has no or modest impact on the durability of NA- or PEG-IFN- induced HBsAg loss, with rates of anti-HBs acquisition increasing over time.11, 17, 18 Clarification of the importance of anti-HBs seroconversion on the durability of HBsAg loss will influence the definition of HBV functional cure and choice of primary efficacy endpoints in clinical trials. Whether duration of consolidation treatment impacts durability of HBsAg loss also needs to be determined and will likely depend on the mechanism of action of specific HBV drugs.

Based on current knowledge, the best surrogate of HBV functional cure is HBsAg loss confirmed on 2 occasions at least 6 months apart without requirement for anti-HBs seroconversion plus undetectable HBV DNA. This should be the primary endpoint in phase III trials and long-term post-treatment follow-up data should be systematically collected to document durability of HBsAg loss, rate of anti-HBs seroconversion, and impact on clinical outcomes.

Decline in HBsAg Levels as Predictor for HBsAg Loss in Early Phase Trials

HBsAg loss must be preceded by a decline in HBsAg levels.19 As HBsAg may be expressed from both cccDNA and integrated viral DNA sequences, quantitative HBsAg levels correlate modestly with intrahepatic cccDNA concentration; newer biomarkers such as hepatitis B core related antigen (HBcrAg) and HBV RNA may better reflect cccDNA status.20 Early declines in serum HBsAg on treatment are associated with HBsAg loss during or after treatment, though with higher negative than positive predictive value.19 The ability of HBsAg decline to predict HBsAg loss may be affected by HBeAg status, HBV genotype, and the type/target of the treatment used.19, 21

Therefore, a decline in HBsAg levels in phase II clinical trials should currently only be considered as an exploratory and not a surrogate endpoint. A decline of HBsAg as a surrogate marker in phase III trials can only be accepted if it is demonstrated (i.e., in phase II trials) to reliably predict HBsAg loss. A better predictor for HBsAg loss may be a reduction in HBsAg level to a low level, e.g., <100 IU/mL of HBsAg (reviewed in19). However, more data would be required to determine whether a specific threshold level predicts HBsAg loss and whether this can be applied to all antiviral and immunomodulatory therapies regardless of mechanism of action. Surrogate endpoints of HBV functional cure measure biochemical, virological and histological outcomes.

Reliability of Current HBsAg Assays to Assess HBV Functional Cure

Current clinical assays for HBsAg have a lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) and lower LLOD of around 0.05 IU/mL and can detect common HBV S variants. New assays have increased sensitivity (LLOD and LLOQ of ~0.005 IU/mL), but the clinical relevance of low levels of HBsAg (0.005-0.05 IU/mL) is unclear.22-24 There are 2 sources of circulating HBsAg, cccDNA and integrated HBV DNA, with the latter suggested to be a more important source of HBsAg in HBeAg-negative patients.25 The efficacy of new antiviral or immunomodulatory therapies that inhibit or clear cccDNA may not be well-reflected in HBsAg measurement if integrated HBV DNA continues to produce HBsAg—unless antiviral immune responses are restored and hepatocytes capable of producing HBsAg from cccDNA as well as integrated HBV DNA are eliminated. Thus, persistent detection of serum HBsAg may reflect transcription and translation from integrated HBV DNA rather than from cccDNA. The inability of current diagnostic tests to differentiate between HBsAg derived from integrated HBV DNA versus cccDNA may raise doubt about the use of HBsAg as an endpoint for therapy; future studies will need to ascertain whether HBsAg derived from integrated versus cccDNA influences outcomes.

Serum HBV RNA as a Measure of cccDNA and HBV Transcription

A liver biopsy is required to quantify cccDNA. However, specific cccDNA measurement remains technically challenging, due to the coexistence of nearly identical HBV DNA replicative forms in the liver, and standardised assays are not currently available. Serum biomarkers reflecting the intrahepatic cccDNA concentration and transcriptional activity are desirable and a growing body of literature suggests that circulating HBV RNA may serve this purpose.26, 27 Serum HBV RNA is likely a mixture of intact, pregenomic (pg) and subgenomic, spliced, truncated, and polyA-free species.26 Serum HBV RNA, particularly pgRNA, is the most direct measure of cccDNA transcriptional activity and recent data show that serum HBV pgRNA levels correlate with intrahepatic pgRNA and cccDNA content.26

Serum HBV pgRNA is enriched during NA therapy due to blockage of reverse transcription of pgRNA into HBV DNA. It has been shown that detection of serum HBV RNA predicts post-treatment viral rebound when NA therapy is stopped.28 Serum HBV RNA measurements could also be used to monitor the effectiveness of drugs targeting cccDNA transcription and/or pgRNA stability.29, 30 However, more research is needed to further characterise the composition of circulating HBV RNA and to assess its role in monitoring response to HBV treatment.26 In addition, assays for serum HBV RNA must be standardised and validated to ensure that only HBV RNA (and not a mixture of HBV RNA and HBV DNA) is measured, to delineate the type of HBV RNA measured (pgRNA vs. total HBV RNA vs. spliced RNA vs. truncated RNA), and to define the clinical utility of the assays.

Serum HBcrAg as a Measure of cccDNA and HBV Translation

The HBcrAg assay measures the combined antigenic reactivity resulting from denatured HBeAg, HBV core antigen and a truncated incompletely processed precore/core protein (p22cr); its use for disease monitoring and prognostication of CHB has also been advocated.31-33 Recent data suggest that HBcrAg correlates well with intrahepatic cccDNA and its transcriptional activity.34 In situations where serum HBV DNA levels have become undetectable, the presence of HBcrAg indicates continued transcription from cccDNA. HBcrAg has been shown to predict clinical relapse after stopping NA treatment and spontaneous or treatment-induced HBeAg seroconversion.33, 35 HBcrAg levels are significantly higher in HBeAg-positive patients as current assays also measure HBeAg. There is potential clinical utility in using HBcrAg to monitor the response to new HBV treatments that target cccDNA, either directly or indirectly.34 The sensitivity of current HBcrAg assays appears adequate for monitoring untreated patients with high viremia, but it needs to be improved for monitoring response on antiviral treatment.31, 32

Other Markers

Additional viral markers that may help to stratify patients or monitor the success of novel therapies are emerging20 but require further evaluation in larger studies. Quantitative hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) might be a useful marker of HBV-induced liver disease and might help to discriminate phases of chronic HBV infection and to predict sustained response to antivirals, as well as risk of HBV reactivation in HBsAg-negative patients.36, 37 New assays that can detect HBsAg bound to anti-HBs in immune complexes may be important for confirming HBsAg loss, particularly with therapies that specifically target HBsAg production (e.g., siRNA-based therapies).38

In addition to viral antigens or antibodies and viral DNA or RNA, assessment of host immune responses may be useful for the evaluation of patients with HBV and the efficacy of immunomodulatory therapies. For example, several studies suggest that soluble inflammatory mediators such as serum interferon-inducible protein-10 levels (IP-10 or CXCL-10) are associated with HBsAg decline during PEG-IFN or NA therapy.39 However, standardised assays are lacking. There is also a need for clinical immunology assays to measure the restoration of HBV-specific T cell function and to evaluate the efficacy of novel immunomodulatory therapies in clinical trials.

A full understanding of the biological relevance of these biomarkers is important, as the same biomarker may be used to measure target engagement or endpoint of therapy depending on the mode of action of the studied drug.

Current Therapies for Chronic HBV and HDV Infection

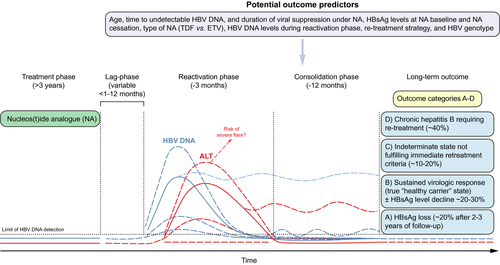

The currently approved NAs, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, tenofovir alafenamide, and entecavir, are highly effective and well tolerated. NAs have been shown to reduce progression towards cirrhosis, liver failure and HCC.15, 40, 41 Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and entecavir are available as generic drugs at relatively low cost in most parts of the world. Tenofovir alafenamide has less adverse effects on bone density and renal function compared with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and similar antiviral efficacy.42 The major issue with NAs is that virologic relapse (generally defined as serum HBV DNA >2,000 IU/mL) as well as clinical relapse, generally defined as serum HBV DNA >2,000 IU/mL and ALT >2 times the upper limit of normal (>2× ULN), are common when treatment is discontinued, even among patients who have had undetectable serum HBV DNA on treatment for many years43, 44 (Fig. 1).

PEG-IFN monotherapy, the other approved therapy for HBV, is finite and may achieve higher HBsAg clearance rates, especially in patients with genotypes A and B. However, long-term HBsAg loss 5 years post treatment is less than 20%. Furthermore, its use is limited due to side effects. Thus, stopping rules based on a decline in HBsAg levels after 12 or 24 weeks of PEG-IFN treatment have been proposed if the chance of sustained virologic control is low.45 There is no approved therapy for the treatment of chronic hepatitis D. Use of PEG-IFN is the only treatment option for chronic hepatitis D. However, 48- or 96-weeks of therapy results in very low rates of sustained off-treatment HDV RNA suppression.46-48

Current HBV treatments are well-established, but there remains debate regarding when to start and when to stop. In terms of starting treatment, both EASL and AASLD guidelines recommend treatment of patients with cirrhosis and those with HBeAg positive or HBeAg-negative active disease, but there are other groups for whom the benefit is less clear.15, 40, 41 Current guidelines do not recommend routine treatment for patients with HBeAg-positive chronic infection (also known as “immune-tolerant” phase) because these usually young patients (below the age of 30-40 years) are at low risk of developing liver cirrhosis or HCC in the short-term, spontaneous immune control with HBeAg seroconversion may occur at a later point in time, and current treatment rarely results in HBeAg or HBsAg loss.49 However, early treatment would reduce HBV DNA replication with the potential benefits of limiting HBV transmission and reducing the future risk of liver complications. Thus, these patients would be candidates for treatment if highly effective and finite therapies were available. Current guidelines also do not recommend treatment of HBeAg-negative chronic infection (inactive carriers), though definitions of inactive carriers are not uniform across different guidelines and should be harmonised.15, 40, 41 These patients would be candidates for therapy, if finite treatments that were highly effective at clearing HBsAg were available.

In terms of stopping treatment, EASL and AASLD guidelines recommend indefinite NA treatment for patients with cirrhosis.15, 40, 41 For HBeAg-positive patients without cirrhosis, NAs may be discontinued in those who achieved HBeAg seroconversion and completed at least 12 months’ consolidation treatment. For HBeAg-negative patients without cirrhosis, EASL guidelines suggest that stopping NA therapy may be considered in selected patients without cirrhosis who have undetectable serum HBV DNA for at least 3 years, provided close monitoring post-treatment is possible, whereas AASLD guidelines recommend indefinite treatment except for those who lose HBsAg.15, 40 Among HBeAg-negative patients who discontinue NA therapy, viral relapse is almost universal and some may experience transient mild hepatitis flares but a proportion will remain in clinical remission off treatment and not need retreatment in the short term.43, 50, 51 Small studies in Europe have reported rates of HBsAg loss as high as 20%-30% within 3 years of stopping NAs, whereas studies in Asia have reported lower rates of HBsAg loss (<10%) after similar durations of off-treatment follow-up.50-55 Moreover, clinical relapse, hepatitis flares, and hepatic decompensation can occur when NAs are stopped.56 Biomarkers that reliably predict whether patients will require retreatment or remain in remission are limited, with low HBsAg level (variably defined) at the time when NAs are stopped being the best studied predictor of sustained clinical remission and HBsAg loss after cessation of therapy.19 However, most studies were retrospective with heterogeneous criteria for resuming treatment and a variable duration of follow-up. More robust data are needed if patients withdrawn from NA therapy are to serve as a reference for assessing efficacy of finite courses of HBV therapies aimed at functional cure.

New Therapies and Mode of Action

With improved knowledge of the viral life cycle, the investigation of antivirals with novel modes of action is an active and promising area in HBV research (summarised in Table 2). New treatments with novel modes of action are being developed for the treatment of HBV.

| Compound | Phase of Development | Comments/Data |

|---|---|---|

| HBV entry inhibitors | ||

| NTCP inhibitor, Myrcludex B (Myr Pharmaceuticals) | Phase III (Hepatitis D) | Strong effect on serum HDV RNA levels, induced ALT normalisation under monotherapy111 |

| Phase I/II (Hepatitis B) | ||

| Cyclosporine analogues | Preclinical | Several cyclosporine derivatives inhibited HBV infection with a sub-micromolar IC50 with no inhibition of bile acid uptake112 |

| Targeting cccDNA (Destabiliser, epigenetic regulators, endonucleases) | ||

| cccDNA destabiliser, ccc_R08 (Roche) | Preclinical | First-in-class orally available HBV cccDNA destabiliser achieved sustained HBsAg and HBV DNA suppression in a mouse model60. |

| Targeted endonuclease, CRISPR/CAS9 | Preclinical | Cleavage of cccDNA by Cas9 showed reduction in both cccDNA and other parameters of viral gene expression and replication in vitro61 |

| Targeting HBx | ||

| CRV431 (ContraVir) | Phase I | Cyclophilin inhibitor that prevents Cyclophilin A-HBx complex formation and HBV replication113 |

| Nitazoxanide (Romark) | Phase II | First-in-class thiazolide originally developed as antiprotozoal agent. Inhibits HBV transcription from cccDNA by targeting the HBx–DDB1 interaction.66 A pilot trial showed antiviral efficacy114 |

| Core protein (Capsid) assembly modulators (CPAMs) | ||

| NVR 3-778 (Novira, Janssen Pharmaceutica) | Development discontinued | First in-class CpAM showed reduction of HBV DNA and HBV RNA, greater effect in combination with PEG-IFN75 |

| ABI-H0731 (Assembly Bioscience) | Phase IIa | CpAMs showed high antiviral efficacy in phase I and IIa studies with >2 log decline of HBV DNA. HBV RNA decline is stronger with CpAM (ABI-H0731) compared to NA therapy118-124 |

| RO7049389 (Roche) | Phase II | |

| JNJ-56136379 (Janssen) | Phase II | |

| AB-506 (Arbutus) | Phase I | |

| ABI-H2158 (Assembly Bioscience) | Phase I | |

| GLS4JHS (Jilin University) | Phase I/II | |

| EDP-514 (Enanta) | Preclinical | |

| GLP-26 (Emory University) | Preclinical | |

| ABI-H3733 (Assembly Bioscience) | Preclinical | |

| HBsAg release inhibitors | ||

| Nucleic acid polymers (REP compound series) (Replicor) | Phase II | Small studies with REP compounds (i.v. application) in combination with TDF and PEG-IFN in HBV monoinfected and HBV/HDV co-infected patients show strong HBsAg decline77, 78 |

| Inhibition of gene expression/gene silencing | ||

| Antisense oligonucleotides and locked nucleic acids | ||

| GSK3389404 (GlaxoSmith Kline) | Phase II | Methoxyethyl antisense oligonucleotide conjugated to N-acetylgalactosamine moieties. Acceptable safety and pharmacokinetic profile in phase I68 |

| Locked nucleic acid platform-based single-stranded oligonucleotides (Roche) | Preclinical | Liver-targeted single-stranded oligonucleotide therapeutics based on the locked nucleic acid platform. Rapid and long-lasting reduction of HBsAg in a mouse model67 |

| RNA interference | ||

| ARC-520 (Arrowhead) | Development discontinued | Decrease in HBsAg level in HBeAg-positive but not in HBeAg-negative patients25 |

| JNJ-3989 (Janssen) formerly ARO-HBV-1001 (Arrowhead) | Phase I/II | HBsAg reduction in HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients. Majority of patients achieved HBsAg <100 IU/mL69 |

| AB-729 (Arbutus) | Preclinical | Activity in vitro and strong HBsAg reduction in mice115 |

| ALN-HBV (Alnylam) | Preclinical | Profound and durable HBsAg silencing in vitro and in vivo116 |

| Targeting the viral RNA post-transcriptional regulatory element | ||

| Dihydroquinolizinone compounds | Preclinical | Specific blockage of the production of HBV DNA and viral antigens70, 72, 117 |

| RG7834 (Roche) | ||

| AB-452 (Arbutus) | ||

- For drugs in preclinical development the list may not be complete.

- Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; Anti-HBs, antibody to HBsAg; cccDNA, covalently closed circular DNA; CpAMs, core protein assembly (or allosteric) modulators; NA, nucleos(t)ide analogue.

HBV Entry Inhibitors

Knowledge of how HBV enters the hepatocyte has led to the development of entry inhibitors.57 These inhibitors can be classified according to their modes of action: (1) Neutralising antibodies target the antigenic loop of HBV S-domain or N-terminal epitopes in the preS1-domain; (2) Attachment inhibitors that bind the virus (e.g., heparin) or cellular heparan sulphate proteoglycans (e.g., poly-Lysin); (3) Substrates of sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide (NTCP) including conjugated bile salts or other small molecules; (4) NTCP inhibitors, such as the myristylated pre-S1 peptide Myrcludex-B, cyclosporin A and derivatives. The latter agents block receptor function at non-saturating concentrations with a long half-life at the receptor, and can also block transport of bile salts and other NTCP substrates at higher concentrations.57

Targeting Covalently Closed Circular (ccc) DNA and its Transcriptional Activity

In cultured hepatocytes, several cytokines (IFN-α, lymphotoxin-β receptor agonists, IFN-γ and tumour necrosis factor-α) have been shown to modulate pathways leading to the upregulation of APOBEC3A/B deaminases, which in turn induce non-cytolytic, partial degradation of cccDNA.58 The discovery of small molecules that are able to inhibit cccDNA formation59 or destabilise the already established cccDNA are being explored. A compound was recently reported to decrease the cccDNA pool in hepatocyte culture and in preclinical mouse models.60 DNA cleavage enzymes specifically targeting cccDNA, including homing endonucleases or meganucleases, zinc-finger nucleases, TALENs (transcription activator-like effector nucleases), and CRISPR-associated (Cas) nucleases, are being investigated in experimental models.61, 62 Delivery issues and avoiding unintended off-target effects, including chromosomal recombination, of these gene-editing techniques will need to be addressed before they can be investigated in human trials.

As well as destroying and damaging cccDNA, it may also be possible to block its transcriptional activity and shut-down viral protein expression. IFN-α has been shown to decrease cccDNA transcription via epigenetic modifications in preclinical models.63 HBx is known to be required for cccDNA transcription and may therefore be an attractive viral target to silence not only cccDNA transcription but also several other HBx-dependent virus-related cellular interactions.64

It was recently shown that pevonedistat, a NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor, restored Smc5/6 protein levels and suppressed viral transcription and protein production in cultured hepatocytes.65 Nitazoxanide, a thiazolide anti-infective agent that has been approved by the FDA for protozoan enteritis, was shown to efficiently inhibit the HBx-DDB1 protein interaction, restore Smc5 protein levels and suppress viral transcription and viral protein production in the same cell culture models.66

Inhibition of Gene Expression

Oligonucleotide-based gene expression inhibitors are either single-stranded-DNA-like molecules or double-stranded small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). Single-stranded oligonucleotides working through RNase-H-mediated mRNA degradation can block viral protein expression and inhibit viral replication. Delivery can be achieved, for example, by conjugating the single-stranded oligonucleotides to N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) moieties. Different single-stranded oligonucleotides are under development.67, 68

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) can be designed to target any viral transcript and induce its degradation by the RISC/Ago2 complex resulting in gene silencing. In a phase II study, a single dose of ARC-520 in combination with entecavir resulted in a profound and durable decrease in serum HBV DNA in both HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients and a decrease in HBsAg level in HBeAg-positive but not in HBeAg-negative patients.25 The siRNAs were designed to target the 3′ co-termini of all transcripts from cccDNA. The lack of effect on HBsAg level in HBeAg-negative patients was postulated to be caused by altered viral transcript sequences derived from integrated HBV DNA resulting in the truncation of the 3′ end of the transcripts.25 The re-design of the siRNA to target viral transcripts generated from integrated as well as cccDNA viral sequences, and the development of new formulations based on GalNAc delivery, allowed for subcutaneous administration and improved effects on serum HBsAg levels in both HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients in phase I/II clinical trials.69 Different siRNA compounds are in preclinical and clinical development (Table 2).

Recently, small molecules belonging to the dihydroquinolizinone series were shown to induce HBs mRNA degradation by targeting a post-transcriptional regulatory element, leading to a reduction of both viral antigens and viral DNA in vitro70, 71 and in a preclinical mouse model.72

More data are needed to determine whether the decline in HBsAg production induced by these strategies can be sustained off treatment and if treatments that target HBsAg production alone might be sufficient to restore HBV-specific immunity, or if additional antiviral or immunomodulatory therapies are needed.

Nucleocapsid Assembly and pgRNA Packaging

The HBV core protein has recently emerged as a promising direct antiviral target as it is involved in many aspects of the viral lifecycle. Following the elucidation of the 3-dimensional structure of the core protein, several classes of non-nucleoside small molecules called core protein assembly (or allosteric) modulators (CpAMs) have been developed, including phenylpropenamide and heteroaryldihydropyrimidine derivatives. These molecules can strengthen protein-protein interactions, inhibit pgRNA encapsidation, and block DNA synthesis. There are different classes of CpAMs.

Heteroarylpyrimidine derivatives induce capsids with aberrant morphology and core protein aggregates, while phenylpropenamide derivatives or sulfamoylbenzamide derivatives allow the formation of capsids with normal morphology but which are devoid of pgRNA (empty capsids). In comparison to NAs, CpAMs have distinct modes of action; for example, they inhibit pgRNA encapsidation and cccDNA formation, presumably by inhibiting the capsid uncoating step.73, 74 The first compound studied in humans was NVR3-778; in a dose ranging phase Ib study, serum HBV DNA and HBV RNA decreased but a decline in HBsAg was mainly observed when combined with PEG-IFN.75 Several CpAMs are in preclinical and clinical studies (Table 2).

Targeting HBsAg

Abundant circulating HBsAg may contribute to immune exhaustion. Direct inhibition of HBsAg secretion is a promising line of investigation. Nucleic acid polymers (NAPs) are broad spectrum antiviral agents that may block the release of HBsAg but the exact mode of action still needs to be elucidated. Different NAPs (REP 2055, REP 2139, REP 2165) used either as monotherapy or in a combination with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and PEG-IFN (following lead-in with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) induced HBsAg clearance and anti-HBs seroconversion in a high proportion of patients with HBV infection.76, 77 Similar results were observed in pilot studies of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and PEG-IFN in combination with REP 2139 or REP 2165 in patients with chronic HBV and HDV coinfection.78 ALT flares were common during treatment and seemed to be correlated with the introduction of PEG-IFN, but they were not accompanied by signs of liver dysfunction. Larger clinical studies with longer duration of follow-up are needed to confirm the durability of response and long-term safety, especially the potential for cytotoxicity resulting from intracellular retention of HBsAg.

Immunomodulatory Therapies

Current direct-acting antiviral therapies are very efficient in controlling viral replication, but these treatments require long-term administration and HBsAg loss is rare.16 Immunotherapy, either de novo or after NA-suppressed virus replication, may be able to maintain virologic suppression or low levels of HBV replication under the control of a functional host antiviral response (Table 3). Multiple aspects of the immune responses to HBV are defective in chronic infection but the virus remains susceptible when these are boosted.79, 80 Inducing robust intrahepatic immune surveillance is likely required for a long-term functional cure.

| Compound | Phase of Development | Comments/Data |

|---|---|---|

| Targeting cell intrinsic and Innate Immune responses | ||

| RO7020531 (Roche) | Phase I | Combination with the CpAM RO7049389 achieved sustained HBV DNA suppression and HBsAg loss in a mouse model125 |

| TLR 7 agonist | ||

| Vesatolimod, GS-9620 (Gilead) | Phase II | Dose-dependent pharmacodynamic induction of ISG15 and host NK and HBV-specific T cell responses but no HBsAg reduction in patients.87, 88 Lack of effect for cccDNA in vitro126 |

| TLR 7 agonist | ||

| JNJ-4964 (Janssen) | Preclinical | Antiviral efficacy (HBV DNA, HBsAg, liver HBV DNA, HBV RNA) in a mouse model127 |

| TLR 7 agonist | ||

| GS-9688 (Gilead) | Phase I | Induced IL-12 and IL-RA1 in humans. Short duration did not result in HBsAg decline128 |

| TLR 8 agonist | ||

| AIC649 (AiCuris) | Phase I | Increased IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and IFN-γ and reductions in IL-10 levels129 |

| TLR 9 agonist | ||

| Inarigivir soproxil (Spring Bank) | Phase II | Dual mode of action: RIG-I Agonist and interference with the interaction of the viral polymerase and pgRNA. The ACHIEVE trial showed dose-dependent antiviral response on HBV DNA and HBV RNA92 |

| RIG-I agonist | ||

| Targeting adaptive immune responses | ||

| Checkpoint Inhibitors | Phase I | Single dose of Nivolumab (with or without GS4774) showed HBsAg reduction >0.5 log in some patients96 |

| Nivolumab (Opdivo, Bristol-Myers Squibb) | ||

| TG1050/T101 (Transgene/Talsy) | Phase I | Induction of T cell responses in mouse models and reduction of viral parameters.130 Dose-related immunogenicity in patients but so far only preliminary data on clinical effects.131 |

| Non-replicative adenovirus serotype 5 encoding 3 HBV proteins (Therapeutic Vaccine) | ||

| CPmutS (Vaccitech) | Phase I | Robust T cell and anti-HBs response in mice132 |

| Adjuvanted ChAd and MVA vectored therapeutic HBV vaccines | ||

| HepTcell (Altimmune) | Phase I | Human T cell responses against HBV markedly increased over baseline compared to placebo but no effect on HBsAg133 |

| HBV Peptide therapeutic vaccine with TLR9 adjuvant IC31 | ||

| JNJ-64300535 (Janssen) | Phase I | No clinical data (NCT03463369) |

| Electroporation of DNA vaccine | ||

| INO-1800 (Inovio) | Phase I | Activated and expanded CD8+ killer T cells (www.inovio.com). |

| DNA plasmids encoding HBsAg and HBcAg) plus INO-9112 (DNA plasmid encoding human interleukin 12) | ||

| GS-4774 (Globeimmune, Gilead) | Development discontinued | No significant reductions in serum HBsAg in phase II134 |

| Heat-inactivated, yeast-based, T cell vaccine | ||

| Genetically engineered T cells / Monoclonal or bispecific antibodies | Preclinical | Reductions in HBsAg and HBV DNA in mouse models101, 102 |

- For drugs in preclinical development the list may not be complete.

- Abbreviations: cccDNA, covalently closed circular DNA; pgRNA, pregenomic RNA.

Interferons

IFN-α has been used to treat both chronic HBV and chronic HDV infection. HBsAg loss rates after a finite course of IFN-α therapy are higher than after NA therapy. IFN-α induces expression of IFN sensitive genes encoding intracellular or secreted effector proteins with antiviral properties. IFN-α has also been shown to inhibit pgRNA encapsidation, enhance cccDNA degradation, and to exert epigenetic modification of cccDNA transcription.81 The immunomodulatory effect of IFN-α is complex. One mechanism is the expansion of natural killer cells that have antiviral activity.82 There is still a need to better understand the mechanisms of action of IFN-α and the basis for the higher rates of response in genotype A and B infection. The drawbacks of IFN-α include the side effect profile and the relatively low response rate overall.83

Stimulation of Pathogen Recognition Receptors

The initial sensing of infection is mediated by these receptors; thus, they are a crucial element of the innate immune response. Pharmacological activation of the intrahepatic innate immune response with toll-like receptors (TLR) 7, 8, or 9 has been studied.80 GS-9620, an oral agonist of TLR7, induced a decline in serum HBV DNA and HBsAg levels, as well as in hepatic HBV DNA levels in HBV-infected chimpanzees.84 Similar effects have been observed in woodchucks85 but not in humans,86, 87 despite the induction of host natural killer and HBV-specific T cell responses.88 The discrepancies between results in animal models and humans highlight the importance of testing new therapies in humans at an early stage in drug development. Other TLR7 and TLR8 agonists are in clinical development (Table 3).

Stimulator of Interferon Genes Agonists

The stimulator of IFN genes (or STING) is the adaptor protein of multiple cytoplasmic DNA receptors and can be activated by cyclic dinucleotides.89 Therefore, like TLR7/8, stimulator of IFN genes might be activated by other small molecules and thus be a potential target for pharmacological activation of the innate immune response, as well as priming of an adaptive immune response. Stimulator of IFN genes agonists can also be used as adjuvants to therapeutic vaccination. Retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I, also called DDX58) induces both IFN type III and cytokine production and inhibits HBV replication by interfering with the interaction of the viral polymerase and the epsilon structure of pgRNA.90 SB 9200 (Inarigivir), an oral prodrug of the dinucleotide SB 9000, is thought to activate RIG-I and nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain-containing protein 2, resulting in IFN-mediated antiviral immune responses in virus-infected cells, and decreased serum woodchuck hepatitis virus DNA and surface antigen levels.91 Ongoing clinical trials have shown a mild decrease in serum levels of HBV DNA, HBV RNA and HBsAg in response to SB 9200 therapy.92

Checkpoint Modulation

The lack of a T cell mediated response in chronic HBV is partly due to overexpression of co-inhibitory receptors including programmed cell death 1 (PD-1), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), or T cell immunoglobulin and mucin protein 3 (TIM-3).79 Immunosuppressive cytokines, such as IL-10, may also impair T cell function and be responsible for HBV-specific T cell exhaustion. Blockade of these co-inhibitory receptors may reverse immune dysfunction in chronic HBV infection as demonstrated ex vivo93, 94 and in animal studies.95 This approach is being evaluated in human studies in combination with therapeutic vaccination.96

Therapeutic Vaccination

The goal of therapeutic vaccination is to stimulate or boost the host immune response to restore immune control, which should then lead to sustained suppression of HBV replication and ultimately HBsAg loss. Several therapeutic vaccines have been studied in patients with CHB. Although these vaccines have shown some success in animal models, results in humans have been disappointing.97 Novel combination approaches that create a favourable immune environment are being explored to enhance the efficacy of these vaccines. These include combinations with checkpoint inhibitors, TLR or RIG-I agonists, and/or other strategies to decrease viral antigen load.

Engineered HBV-Specific T Cells

The rarity of HBV-specific immune cells in patients with CHB, and their exhausted phenotype and metabolic alterations98, 99 have driven the development of newly engineered HBV-specific T cells.100 T cells able to recognise HBV-infected cells have been constructed using a chimeric antigen receptor (made of an anti-HBs-specific antibody) or using canonical HLA-class I restricted HBV-specific T cell receptors. Preliminary results using these approaches are encouraging, with specific reductions of HBV-infected hepatocytes, HBsAg and HBV DNA in preclinical models.101-103 Their use in patients with HBV-related HCC is being investigated.104

Immunomodulatory therapies currently in development are supported by a strong scientific rationale, but their efficacy in patients with CHB has not yet been demonstrated (Table 3). Future clinical trials of immunomodulatory therapies will need to explore the role of lead-in antiviral therapies, in terms of suppression of both HBV replication and HBsAg production, to determine if their use will result in a higher likelihood of restoring immune control. Combinations of innate immunity boosters and stimulation of adaptive immunity may also be required.

Clinical Trials Aimed at HBV Functional Cure

Assessment of Safety and Indications for Stopping Trials of New HBV Therapies

Given the well-established safety of NAs, the safety of new HBV therapies will need to be comparable and, if additional risk is anticipated, this must be justified by the expected improvement in clinical outcomes. A major concern in HBV drug development is the occurrence of ALT flares. Three types of flares are proposed (Table 4): “immune-associated or antiviral flares” (due to host immune responses, accompanied by decline in HBV DNA and viral antigen levels); “virus-induced flares” (due to enhanced viral activity, either related to a lack of efficacy or drug resistance); and “drug-induced flares” (due to undesired effect of drug, such as autoimmunity or drug-induced liver injury [DILI]).

| Antiviral Flare | Virus-Induced Flare | Drug-Induced Flare | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Timing of flare | Variable depending on mechanism of drug | May be early if due to lack of efficacy, and variable if due to antiviral drug resistance | Any time during treatment |

| Course of flare | Usually self-limiting within weeks | Progressive if not recognised and remedied | Static or progressive |

| Association with HBV DNA | After HBV DNA decline | Preceded by HBV DNA increase | Unrelated |

| Alkaline phosphatase level | Normal | Normal | Normal or elevated |

| Bilirubin level | Usually normal | May be elevated | Normal or elevated |

| Liver biopsy | Not needed | Not needed | May be needed for diagnosis |

- Abbreviation: ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

The FDA recommendation on DILI management does not apply to patients with underlying liver disease who usually have elevated liver enzymes at baseline; therefore, a new approach has been proposed that considers both elevations of baseline ALT as well as ALT elevations during treatment105 (Table 5). There is agreement that flares associated with an increase in bilirubin or international normalised ratio (INR) or hepatic decompensation require prompt discontinuation of investigational therapy. It is unclear whether ALT values that trigger halting of treatment can be relaxed, e.g., extending above 10x ULN in cases of “antiviral” flares, if there is no hepatic decompensation, or increase in bilirubin or INR. If relaxed, this would only apply to patients without advanced fibrosis and in whom HBV DNA levels are decreasing. Flares occurring in virally suppressed patients receiving NAs may be more concerning, as these likely reflect DILI, though they may also reflect immune restoration, especially in patients receiving immunomodulatory therapies. To differentiate the types of flares, it is pertinent to consider their timing, course, associated changes in HBV DNA levels, and any concomitant increase in alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin. In some instances, a liver biopsy may be necessary to resolve the cause of the flare (Table 5). All patients with flares need to be closely monitored to determine whether treatment needs to be halted and if so when treatment can be resumed. Flares may also occur after treatment is stopped due to viral rebound or immune recovery, or delayed liver toxicity. Thus, close monitoring after discontinuation of treatment is mandatory.

| Baseline ALT Value | Elevation During Treatment |

|---|---|

| 1 to less than 2× ULN | >5× from baseline and >10× ULN |

| 2 to less than 5× ULN | >3× from baseline |

| Greater or equal to 5× ULN | >2× from baseline |

- Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Design of Phase II and III Trials

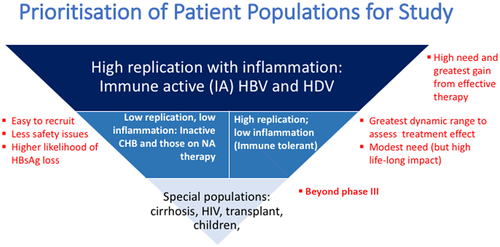

The design of phase II and phase III trials aimed at HBV functional cure requires careful consideration of study populations (Fig. 2). Patients in the immune-active phase with high levels of HBV replication >20,000 IU/mL and hepatic inflammation have the greatest immediate need for treatment and also stand to gain the most from an effective therapy. NA treatment is safe and efficacious in these patients and the major potential advantage of new therapies would be to allow a higher percentage of patients to achieve sustained HBV DNA suppression or HBsAg loss after completing a finite course of treatment. At the opposite end of the spectrum are special populations, e.g., patients with cirrhosis, liver transplantation, and children, for whom the safety and efficacy of new therapies must be established prior to testing. In patients with cirrhosis, hepatitis flares can lead to decompensation and liver-related death/need for liver transplantation; thus, new drug therapies, especially those that are more likely to induce flares, need robust safety data before being evaluated in this population. Patients with HBeAg-positive infection (immune-tolerant phase), who have a low risk of liver complications in the short term, particularly if they are less than 30 years of age, are an important population to consider. A finite therapy with a high rate of HBsAg loss may be especially beneficial for this group, as most are without significant fibrosis and thus achievement of functional cure is anticipated to prevent liver complications in the long term. Effective therapies applied to young patients can also reduce the risk of HBV transmission and stigma associated with HBV infection. Because of the well established safety of nucleos(t)ide analogues, new treatments for HBV will have to be similarly safe, or provide a clinical improvement that justifies any additional risk.

HBV infection is an heterogenous disease and not all therapies can be expected to be effective in all patient groups. Thus, the challenge in phase II studies is identifying patient groups that are sufficiently homogenous for efficacy to be accurately evaluated. The population studied should align with the investigational drug’s mechanism of action. Characteristics of potential importance include baseline HBsAg, HBV DNA or ALT levels, HBeAg status and duration of NA therapy (for those currently on NA). Many phase II studies initially target patients who are virally suppressed on NAs; this has the advantage of being an easily accessible population (most patients with active disease in care are receiving NAs) that is more homogenous and has a lower risk of severe hepatitis flares. Further, given the broad use of NAs in clinical practice, clinical designs may evaluate adding new therapies to NAs or switching from NAs to new therapies versus continuation of NAs. Alternatively, add-on or switching therapies using new antivirals can be compared to withdrawal of NAs to determine whether higher rates of clinical remission or HBsAg loss can be achieved.

To improve efficiency, it is desirable to include multiple patient groups in a single trial. However, it is important to ensure that treatment groups are balanced because of the possibility of heterogeneous responses. Additionally, sufficient numbers of patients must be included to allow for analysis of treatment responses in subgroups. Stratification may be useful, with the factors for stratification influenced by the mechanism of action of the drug. For example, HBV genotype has been used as a stratifying variable in PEG-IFN-based studies. However, due to the modest sample size of phase II trials, stratification may be limited to only 1 or 2 factors; HBeAg might be the most appropriate factor as it “captures” many of the other variables such as HBsAg and HBV DNA levels.

Novel clinical trial strategies should be considered. Adaptive designs allow and even enforce continual modifications to key components of trial design while data are being collected. This approach can reduce resource use, decrease time to trial completion, limit allocation of participants to inferior interventions, and improve the likelihood that trial results will be scientifically or clinically relevant.106, 107 However, these innovative trial designs require careful planning and early communication with regulatory agencies to ensure all requirements for approval are concurrently met. Master protocols are another methodological innovation. This is where one overarching protocol is designed to answer multiple questions. With a properly designed master protocol, evaluation of more than 1 or 2 treatments in more than 1 group of patients can be executed within the same overall trial platform and responses can be compared across treatments or across subgroups receiving the same treatment.108 Regardless of the type of trial design chosen, a study to demonstrate superiority is generally preferred for the endpoint HBsAg loss. However, non-inferiority might also be an option, e.g., rates of sustained viral suppression with a finite treatment similar to maintained viral suppression during long-term NA treatment.

Design of Trials of Combination Therapies for Chronic HBV

Combination therapy will be an essential strategy to improve efficacy and the likelihood of HBV functional cure.109 Many combinations can be envisioned. A key question is whether 2 or even 3 antiviral drugs have additive or synergistic effects on HBV replication. For example, a direct-acting antiviral might be used to lower viral replication and improve innate immune function. A second direct-acting antiviral could then be used to decrease antigen load, which might be able to correct immune exhaustion. Addition of a third direct-acting antiviral aimed at preventing hepatocytes from new infection events may also be considered. Finally, immunostimulatory agents could be added to upregulate T cell mediated clearance of infected hepatocytes. Using sequential or add-on strategies may allow for the correction of immune impairments while minimising side effects due to an overwhelming immune response.

Selection of the appropriate patients for combination therapy is crucial. Patients currently not on treatment and patients who are virally suppressed on NAs could be considered. The latter might be preferred initially as they already have undetectable HBV DNA and may have lower HBsAg levels and thus a higher likelihood of HBsAg loss.

Discussion on Endpoints, Trial Design, and Desired Response Rates

Primary Endpoint for Phase II Clinical Trials

The view of both the EMA and the FDA is that the endpoint in phase II clinical trials should be tailored to the drug in question and the benefit should outweigh the risk, which would then allow subsequent development of the drug. Given that HBsAg loss is the preferred primary endpoint for phase III clinical trials, the debate regarding the endpoint for phase II trials centred on HBsAg decline versus HBsAg loss. While some proposed setting a high bar, i.e., requiring HBsAg loss in at least a small percent of participants to minimise the likelihood of negative phase III trials, others argued for a lower bar in early phase trials, e.g., a >1 or >2 log reduction in HBsAg level or a decrease to <100 IU/mL, to minimise the risk of abandoning promising drugs that need to be administered for longer durations or in combination with other antiviral or immunomodulatory therapies to achieve the desired effects. Participants emphasised that effective suppressive therapies already exist for the management of HBV and the goal of new therapies is to achieve what current therapies cannot, i.e., higher rates of HBsAg loss with a finite duration of treatment. Thus, phase II trials should be looking for an early signal of finite treatment efficacy. A decrease in HBsAg level to <100 IU/ml was proposed as a clinically meaningful endpoint for phase II trials, but HBsAg decline must still be sufficiently validated and scientifically justified.

A decrease in HBsAg level to <100 IU/mL was suggested as a clinically meaningful endpoint because it has been associated with a high probability of subsequent spontaneous HBsAg clearance as well as HBsAg clearance after discontinuation of long-term NA therapy.19 This endpoint might be easier to achieve in patients with low pre-treatment HBsAg level or with drugs that directly target HBsAg production or secretion but may not be appropriate for all phase II trials. The use of HBsAg decline as a surrogate endpoint will need to be sufficiently validated and scientifically justified to ensure progression into phase III clinical trials.

A particular challenge of designing phase II studies is identifying a target population with sufficient heterogeneity to be representative of the population with CHB but not so diverse that it hinders analysis because of multiple subgroups.

Primary Endpoint and Desired Response Rate for Phase III Clinical Trials

A majority felt that HBsAg loss with or without anti-HBs seroconversion 6 months after completion of treatment should be the primary endpoint for phase III trials. Suppression of serum HBV DNA to undetectable levels would also be required. While over two-thirds of the participants voted for “HBsAg loss in ≥30% of patients after 1 year of therapy” as the desired response rate for phase III trials, it must be acknowledged that this target is arbitrary and not sufficiently nuanced to reflect subcategories of patients for whom lower target rates of HBsAg loss may be acceptable. A target, although arbitrary, is required to guide the first wave of drug development, and this target will be re-assessed based on the results of the first phase II and phase III clinical trials. It was emphasised that a “one-size fits all” approach should be avoided as there may be subgroups of patients who respond far better than others and clinical trial design and target response rates should be tailored to patient characteristics. In addition, new treatments that can result in sustained off-treatment HBV DNA suppression after a short (e.g., <2 years) course of therapy in a high percentage of patients should also be considered an improvement over current therapies, even if HBsAg loss is not achieved.

Criteria for Approval of Diagnostic Assays for New HBV Markers Used to Determine Efficacy Endpoints

New assays have been developed to quantify markers of HBV (quantitative HBsAg, HBcrAg, HBV RNA, and anti-HBc) as surrogates for hepatic cccDNA, to confirm target engagement of new antiviral therapies, and to predict HBsAg loss. These assays are currently used in clinical trials of new antiviral and immunomodulatory therapies and need to be standardised and validated such that they can be available for clinical use when new drugs are approved. A majority felt these assays should have demonstrated validity in predicting HBsAg loss while a smaller proportion felt that new HBV markers should have demonstrated utility in guiding therapy.

Prerequisites for Testing a New Therapy in Combination With Other (New or Existing) Therapies

The FDA and EMA requires data on antiviral activity, mechanism of action, safety, and drug-drug interactions. In situations where a new drug is being combined with a pre-existing drug, animal toxicity studies are not required unless there is some non-clinical data indicating that there might be overlapping toxicity. However, some drugs in development that do not demonstrate the intended antiviral activity in phase I or II trials may work synergistically in combination with other drugs. It was suggested that these drugs may be tested if there are no safety concerns and if there is scientific rationale for combination therapies.

Target Patient Population for New HBV Therapies

A majority of the participants voted for “HBeAg-positive or HBeAg-negative CHB virally suppressed on NA” as the target population for initial trials because investigators have easy access to these patients and there is less complexity in interpreting ALT flares. The next target group for new therapies would be HBeAg-positive or HBeAg-negative immune-active patients not currently on treatment. However, some countered that clinical trials should target patients with HBeAg-positive infection (immune-tolerant) first because effective treatments are currently available for immune-active patients, and also because some new strategies in development could have the potential to be particularly effective in this population. One advantage of studying immune-tolerant patients is the homogeneity of this population; but the high HBsAg load might be a bigger challenge for both direct-acting antivirals and immunomodulatory therapies, although the high levels provide a wide dynamic range to quantify direct antiviral effects.

Primary Endpoint for Clinical Trials of New HDV Treatment

Several compounds with different modes of action are currently in clinical development for chronic hepatitis D (Table 6). Surrogate markers and endpoints for HDV treatment are not well defined. Recently, a group of experts evaluated the existing evidence and suggested possible endpoints that could be used across different clinical trials.110 During this endpoint meeting there was no clear agreement on the choice of endpoint for HDV trials; specifically, whether finite treatment or maintenance treatment should be the goal and if these should vary depending upon the phase of study. Participants preferred undetectable serum HDV RNA 6 months after stopping treatment as the endpoint for finite treatment, whereas for maintenance treatment, a 2-log reduction in HDV RNA might suffice. Importantly, HDV RNA assays need to be standardised according to the World Health Organization standard—only standardised assays should be used to evaluate treatment in clinical trials.

| Compound | Phase of Development | Comments/Data |

|---|---|---|

| Entry (NTCP) inhibitor: Myrcludex B (Myr Pharmaceuticals) | Phase III (in progress) | |

| Farnesyltransferase inhibitor: Lonafarnib (Eiger) | Phase III (in progress) |

|

| Interferon: Pegylated interferon-lambda (Eiger) | Phase II |

|

| Nucleic acid polymers: (REP compound series) (Replicor) | Phase II |

|

- Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; GI, gastrointestinal; PEG-IFN, pegylated-interferon; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Ideally, finite treatment should also result in HBsAg loss and long-term follow-up is needed to detect any late relapses. Normalisation of ALT is also desired. A concern in HDV treatment is the possibility of HBV reactivation when HDV is suppressed. To mitigate this risk, NA therapy may be considered in patients before they are enrolled in HDV treatment trials, especially if cirrhosis is present.

Conclusions

Agreement was reached on several important aspects of clinical trials aimed at achieving HBV “cure”. Until there is agreement on a term that is acceptable to all stakeholders including patients, the goal of new HBV treatment is “functional cure” defined as HBsAg loss (based on current assays with LLOD ~0.05 IU/mL) and undetectable HBV DNA (based on current assays). Seroconversion to anti-HBs is desired but not required. The primary endpoint of phase III trials should be HBsAg loss and undetectable HBV DNA 6 months after completion of treatment. HBsAg loss in ≥30% of patients after 1 year of therapy is the desired rate of response in these phase III trials. An intermediate goal may be sustained HBV DNA suppression without HBsAg loss after completing a short course of therapy currently defined as “partial functional cure”. Demonstrated validity in predicting HBsAg loss was voted as the most appropriate criterion for the approval of diagnostic assays for new HBV markers used to determine efficacy endpoints. The safety and antiviral activity of monotherapies should ideally be satisfied before drugs are tested in combination in clinical trials. The HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative immune-active patients who are treatment naïve or are virally suppressed on NAs should be the priority for phase II/III trials aimed at HBV functional cure. Some experts advocated inclusion of patients with HBeAg-positive infection (immune-tolerant) among the priority groups. HBsAg loss is also the ideal primary endpoint for phase III clinical trials of new finite HDV treatments. Undetectable serum HDV RNA 6 months after stopping treatment is an alternative endpoint. Different endpoints can be used for maintenance therapies (e.g., on treatment HDV RNA suppression).

Given the safety of NAs, new HBV therapies will need to have comparable safety or have achievable endpoints that make additional risk justifiable. ALT flares that occur during treatment administration and are associated with an increase in direct bilirubin (>1.0 mg/dL or >20 µmol/L) or INR (>1.5) should prompt temporary or permanent cessation of treatment for all patients regardless of ALT level. In addition, it will also be important to investigate patient preferences and patient reported outcomes in both phase II and phase III clinical trials.

Designing phase II studies is a challenge, particularly with respect to the patient population (sufficient heterogeneity to be informative but yet not too heterogenous as to cloud interpretation of efficacy), choice of intermediate endpoints to support advancing to phase III studies, and the desired response rate. The design of these studies will be dictated by the mode of action of the drugs, the clinical data that exists and the study population.

The agreement gained from this meeting will be instrumental for the planning and design of trials that will provide new treatment options for chronic HBV infection that will be finite, increase the rate of HBsAg loss or sustained suppression of HBV or HDV replication compared to existing therapies, and preserve excellent safety profiles.

Acknowledgment

We thank the following participants (alphabetical order) for their discussion in the closed session: Nezam H. Afdhal, Spring Bank Pharmaceuticals; David Apelian, Eiger; Nathaniel Brown, Hepatitis B Foundation; Maria Beumont-Mauviel, Janssen; Gavin Cloherty, Abbott; Markus Cornberg, EASL; Theodore Dickens, GlaxoSmithKline; Eric Donaldson, FDA; Anuj Gaggar, Gilead Sciences; Bruce Given, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals; Uri Lopatin, Assembly Biosciences; Anna Lok, AASLD; Veronica Miller, HBV Forum; Poonam Mishra, FDA; Gaston Picchio, Arbutus; Peter Revill, ICE-HBV; Silke Schlottmann, EMA; Norah Terrault, AASLD; Andrew Vaillant, Replicor Inc; Laura Vernoux, Fujirebio; Su Wang, Patient representative; Cynthia Wat, Roche; John Young, Roche; Fabien Zoulim, EASL.

Disclaimers

This article reflects the views of the authors and should not be construed to represent US Food and Drug Administration views, guidance or policies; nor the official policy or views of the EMA/CHMP or the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM).

Author Contributions

MC, ASL, NT, FZ organised the HBV endpoint conference, outlined, edited, and approved the final manuscript. The 2019 EASL-AASLD HBV Treatment Endpoints Conference Faculty contributed content and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Appendix

EASL-AASLD HBV Treatment Endpoints Conference Faculty: Thomas Berg (Section of Hepatology, Clinic of Gastroenterology, University Hospital Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany); Maurizia R. Brunetto (Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Pisa and Hepatology Unit, University Hospital of Pisa, Italy); Stephanie Buchholz (Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices, BfArM, Bonn, Germany)**; Maria Buti (Liver Unit, Hospital Universitario Valle Hebron. Barcelona 08021); Henry LY Chan (Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong); Kyong-Mi Chang (Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine; Medical Research, The Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA, USA); Maura Dandri (I. Department of Medicine, University Medical center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg and German Center for Infection Research (DZIF), Germany; Geoffrey Dusheiko (Kings College Hospital and University College London Medical School, London, UK); Jordan J. Feld (Toronto Centre for Liver Disease, Toronto General Hospital, Toronto, Canada); Carlo Ferrari (Unit of Infectious Diseases and Hepatology, Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Parma, Italy); Marc Ghany (Liver Diseases Branch, National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; Harry L.A. Janssen (Toronto General Hospital, University of Toronto, Canada); Patrick Kennedy (Barts Liver Centre, Blizard Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, London, UK); Pietro Lampertico (CRC “A. M. and A. Migliavacca” Center for the Study of Liver Disease, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Università degli Studi di Milano, Milan, Italy); Jake Liang (Liver Diseases Branch, National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA); Stephen Locarnini (Victorian Infectious Diseases Laboratories, Melbourne, Australia); Mala K. Maini (Division of Infection and Immunity, University College London, UK); Poonam Mishra* (Division of Antiviral Products, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, USA); George Papatheodoridis (Department of Gastroenterology, Medical School of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, General Hospital of Athens “Laiko”, Athens, Greece); Jörg Petersen (IFI Institute at the Asklepios Klinik St Georg Hamburg, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany); Silke Schlottmann* (Food and Drug Administration, USA); Su Wang (Saint Barnabas Medical Center, RWJ Barnabas Health, USA, and World Hepatitis Alliance, UK and Hepatitis B Foundation, USA); Heiner Wedemeyer (Essen University Hospital, University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany.

*This article reflects the views of the author and should not be construed to represent US Food and Drug Administration views, guidance or policies.

**This article represents the opinion of the author and does not represent the official policy or views of the EMA/CHMP or the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM).