Abbreviations

-

- ALP

-

- alkaline phosphatase

-

- IBD

-

- inflammatory bowel disease

-

- LOXL2

-

- lysyl oxidase-like protein 2

-

- PSC

-

- primary sclerosing cholangitis

“Blessed is he who expects nothing, for he shall never be disappointed.”

Alexander Pope

In modern hepatology we have sung the song for the advent of effective antifibrotic drugs for decades, recalling the line of a masterpiece of the late Leonard Cohen, “a million candles burning for the help that never came.” We realize but hardly accept that most likely such drugs will not work without resolving the causative problem of a liver disease such as viral hepatitis. In liver diseases with so far unknown etiology, as in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), the task of successful antifibrotic treatment will be pursued even harder.

Lysyl oxidase-like protein 2 (LOXL2) is a member of the large and diverse LOX and LOXL family that promotes stabilization of the extracellular matrix, chemotaxis, cell growth, and cell mobility and may also be engaged in the regulation of bile duct permeability.1-4 Induction of LOXL2 activity was demonstrated in fibrotic liver diseases.5 Therefore, targeting LOXL2 with the monoclonal humanized antibody simtuzumab could potentially have antifibrotic effects, seal leaky bile ducts, and, by inhibiting epithelial–mesenchymal transition, prevent cholangiocarcinoma. All of these potential benefits would make simtuzumab an ideal compound for the treatment of PSC patients. However, the carefully performed placebo-controlled phase 2b trial of simtuzumab presented by Muir et al. in this issue of Hepatology failed to show any clinical benefit. Simtuzumab administrated in two different doses over 96 weeks surprisingly did not even show an effect on liver fibrosis, as determined with various tests including measurement of hepatic collagen content.6 Thus, the list of studies where an anti-LOXL2 strategy with simtuzumab in different diseases failed is growing. These studies, including liver fibrosis due to chronic hepatitis C or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, pancreas cancer, and lung fibrosis, provided negative results despite successful preclinical studies with antimouse/rat-LOXL2 antibodies in various animal models for such diseases.7-10 Now, with the current negative results in hand, one might hubristically debate whether it had been prudent to directly go for a phase 2b design and skip a phase 2a trial in PSC patients.

The reasons that simtuzumab did not measure up to its expectations in the present PSC study remain enigmatic and could be numerous. (1) Simtuzumab does not reach the region where it should act; however, we do not even know whether such a region should be extracellular or intracellular. This could be related to a lack of sufficient tissue penetration or to rapid clearance from the portal field or space of Disse. Alternatively, the compound might also have been degraded or bound by unknown human-specific proteins. Unfortunately, there was no pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic assay available to assess whether LOXL2 indeed was effectively inhibited in PSC livers, which might have helped to resolve this question. (2) The antibody is not antifibrotic in men because non-LOXL2 proteins of the large family of LOXL enzymes might have interfered with selective allosteric target inhibition by simtuzumab. (3) The positive experimental results from testing a monoclonal anti-LOXL2 antibody with high affinity for mouse LOXL2 in Mdr2 (Abcb4) knockout mice and 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine-fed mice may not be representative of human PSC for a number of reasons, including the use of different drugs in mice and humans and different dynamics of fibrosis between humans and rodents. (4) Potential problems in the current study design include erroneous assumptions in regard to progress of liver fibrosis in PSC, wrong chosen time points of starting such a drug in patients with already advanced and fixed liver fibrosis, drug dosing, and treatment duration. (5) The hypothesis that an antifibrotic drug might help in PSC may be wrong! In this respect one might recall the negative results of colchicine treatment in PSC.11 Of note, single antifibrotic treatment strategies in PSC could even perpetuate cholangitis and pericholangitis because typically observed periductal fibrosis may also represent in part a wound healing process of the bile duct in PSC. Thus, from a theoretical point of view, inhibiting liver fibrosis, more specifically periductal fibrosis in PSC, may represent a double-edged sword: saving the liver parenchyma but injuring the bile ducts and portal fields.

Well-designed and carefully performed clinical trials should be undoubtedly published in high-ranked journals such as Hepatology even if results are negative. Beyond that, the current study by Muir et al. provides key valuable clinical information about PSC and useful advice, in particular pointing to some pivotal questions.

This study again demonstrates that serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels are important in PSC because 34% of patients with ALP >324 U/L had clinical events, indicating that ALP serum levels should be used as a stratification factor for clinical trials. Again, liver stiffness was shown to be a meaningful clinical parameter, and an increase >8.7 kPa as measured by transient elastography was indicative of a 6-fold increase of clinical events in PSC patients. There are numerous additional important clinical findings of this study that cannot be discussed in detail here but certainly will trigger important responses and letters from the readers! We also learn from this study that we need to continue the discussion of repeated liver biopsies as being pivotal for high-quality PSC trials. Personally, I think the answer is yes as far as we lack equally valid and reliable noninvasive markers. In addition, we still will gain important information from repeated liver biopsies in PSC patients under verum or placebo treatment, obtaining liver tissue for detailed investigations beyond liver histology (e.g., omics).

One of the hard tasks in developing agents or useful combinations of drugs for the treatment of PSC still seems to be the selection of well-suited surrogate endpoints because the need for liver transplantation or death due to liver failure occur in unsteady intervals in PSC patients. Even so, the risk will remain that we may perform PSC treatment trials of increasing quality by using appropriate surrogate parameters but still with drugs that do not help at all or fail in our specific study population.

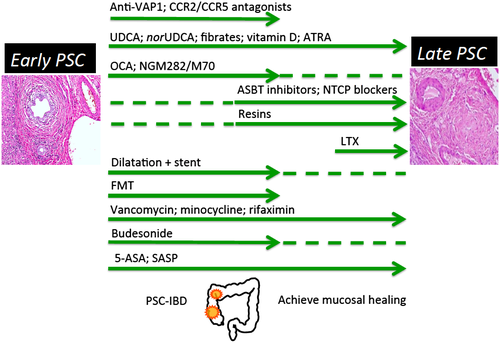

It is likely that the comprehensible goal of precision treatment with one single drug in PSC currently is an overambitious or unrealistic one because we still do not know the cause of PSC. Currently, “PSC” remains a kind of umbrella term and from a clinical perspective a mixed bag. Despite numerous promising approaches, we currently should accept that a successful one-pill strategy would remain unlikely for such a complex disease like PSC. Rather, stage-adapted combination medical therapy is likely to emerge, as already established in chronic congestive heart failure. The highly dynamic development of drugs and treatment strategies for PSC with more than 40 ongoing studies registered at ClinicalTrials.gov underscores the importance for the International PSC Study Group to discuss and validate appropriate study design and to coordinate clinical testing for more rapid progress and best benefit for our patients. Consequently, we should intensify our combined efforts to identify the etiology of PSC, integrating transformative technologies with partners from both different scientific disciplines and industry. In addition, we currently should aim to develop a conceptual framework for a game-changing tailored combination therapy in PSC–inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (Fig. 1). Special emphasis should be given to the fact that PSC patients in an early phase of disease have most likely different medical needs than those in an advanced or late stage. It will be interesting to see whether in the future there will be a place for anti-LOXL2 strategies beside simtuzumab in the treatment of PSC.

Potential conflict of interest

Nothing to report.