Long-term outcomes of entecavir monotherapy for chronic hepatitis B after liver transplantation: Results up to 8 years

Potential conflict of interest: Dr. Yuen received speaker honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Seto advises and is on the speakers' bureau for Gilead and Bristol-Myers Squibb. He is on the speakers' bureau for Novartis.

Abstract

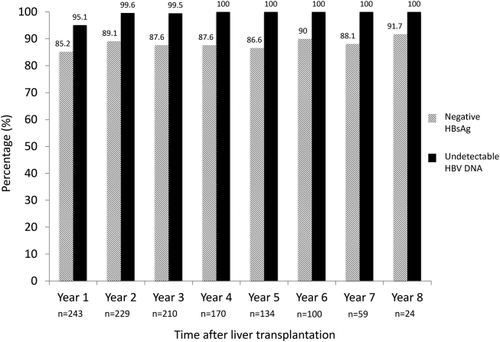

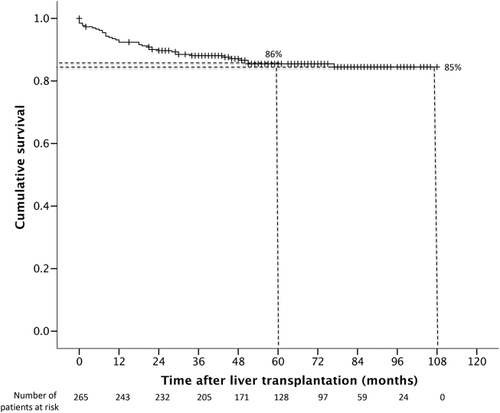

Long-term antiviral prophylaxis is required to prevent hepatitis B recurrence for patients with chronic hepatitis B after liver transplantation. We determined the long-term outcome of 265 consecutive chronic hepatitis B liver transplant recipients treated with entecavir monotherapy without hepatitis B immune globulin. Viral serology, viral load, and liver biochemistry were performed at regular intervals during follow-up. The median duration of follow-up was 59 months. The cumulative rates of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) seroclearance were 90% and 95% at 1 and 5 years, respectively. At 1, 3, 5, and 8 years, 85%, 88%, 87.0%, and 92% were negative for HBsAg, respectively, and 95%, 99%, 100%, and 100% had undetectable hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA, respectively. Fourteen patients remained persistently positive for HBsAg, all of whom had undetectable HBV DNA. There was no significant difference in liver stiffness for those who remained HBsAg-positive compared to those who achieved HBsAg seroclearance (5.5 versus 5.2 kPa, respectively; P = 0.52). The overall 9-year survival was 85%. There were 37 deaths during the follow-up period, of which none were due to hepatitis B recurrence. Conclusion: Long-term entecavir monotherapy is highly effective at preventing HBV reactivation after liver transplantation for chronic hepatitis B, with a durable HBsAg seroclearance rate of 92%, an undetectable HBV DNA rate of 100% at 8 years, and excellent long-term survival of 85% at 9 years. (Hepatology 2017;66:1036-1044).

Abbreviations

-

- anti-HBs

-

- antibody to HBsAg

-

- CHB

-

- chronic hepatitis B

-

- ETV

-

- entecavir

-

- HBIG

-

- hepatitis B immune globulin

-

- HBsAg

-

- hepatitis B surface antigen

-

- HBV

-

- hepatitis B virus

-

- HCC

-

- hepatocellular carcinoma

-

- LAM

-

- lamivudine

For patients undergoing liver transplantation for hepatitis B–related complications, effective antiviral prophylaxis has improved both the short-term and long-term outcome and survival by preventing graft loss and death due to hepatitis B recurrence.1 The use of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) as a prophylactic agent during the 1980s was a major milestone for liver transplant patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.2, 3 The approval of lamivudine (LAM) for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) in 1998 was another major milestone. The major limitation of LAM is the high rate of drug-resistant mutation occurring with long-term use.4 After liver transplantation, the use of LAM monotherapy has been associated with a variable resistance rate of up to 60% at 3 years after transplantation.5-7 The addition of HBIG to LAM reduces the recurrence rate to <5%, and this combined regimen has been adopted by many liver transplant centers leading up to the millennium.

Entecavir (ETV), a cyclic guanosine nucleoside analogue, was approved in 2005. The major advantages of ETV over LAM include the superior antiviral potency and the high barrier to the development of viral resistance. After 7 years of ETV therapy, the resistance rate was only 1.2% compared to 70% for LAM.4, 8 Therefore, the considerable beneficial effects of reducing viral resistance of LAM when combined with HBIG may not be substantiated when ETV is used for liver transplantation. A study of 80 CHB patients treated with ETV monotherapy after liver transplantation with a median follow-up of 26 months demonstrated a high hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) seroclearance rate with excellent virological suppression without evidence of virological rebound.9 However, the follow-up was short, which raised concerns for patients who remained HBsAg-positive and those with HBsAg seroreversion after the initial HBsAg seroclearance after transplantation. A subsequent study reporting on a mixture of nucleoside/nucleotide analogue therapy without HBIG reported excellent long-term outcome and survival.10

In the current study, we aimed to determine the long-term efficacy of ETV monotherapy after liver transplantation for CHB patients with respect to recurrence of hepatitis, virological rebound, and survival.

Patients and Methods

All patients who underwent liver transplantation for CHB-related complications from late 2007 to December 2014 at Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong, and were receiving ETV monotherapy as primary antiviral prophylaxis, without preexisting evidence of lamivudine resistance, were included. No donor organs were obtained from executed prisoners or other institutionalized persons. Patients were all positive for HBsAg for at least 6 months prior to liver transplantation.

Patients were followed up routinely after transplantation at 3-month intervals once clinically stable. Standard laboratory testing including liver biochemistry and alpha-fetoprotein were measured. Viral serological markers were determined including HBsAg, antibody to HBsAg (anti-HBs), hepatitis B e antigen, and HBV DNA. The HBV DNA level was measured using the COBAS TaqMan assay (Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ) with a lower limit of detection of 10 IU/mL.

ANTIVIRAL PROPHYLAXIS

Since late 2007, ETV monotherapy has been used to prevent hepatitis B reactivation and recurrent graft hepatitis with subsequent graft loss for those without evidence of LAM resistance. The standard dose of 0.5 mg daily was used, although 9 patients initially were treated with a 1-mg dose, which was later changed to 0.5 mg daily. No HBIG was used before, during, or after transplantation; and therapeutic vaccination was not routinely used.

IMMUNOSUPPRESSION

The standard protocol immunosuppression for all patients included induction therapy with basiliximab and tacrolimus with or without mycophenolate mofetil. A tacrolimus concentration target of 8-10 ng/mL was adopted for the initial 3 months, followed by 5-8 ng/mL thereafter. For those who were unable to tolerate tacrolimus or required additional immunosuppression, alternative agents including cyclosporine, sirolimus, everolimus, and corticosteroid were used.

SURVEILLANCE FOR HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA

For patients transplanted for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), regular surveillance at intervals of 3-6 months was performed using triphasic contrast computed tomographic or magnetic resonance imaging scanning. No chemotherapy was used in the posttransplant period for those with HCC at the time of transplant.

TRANSIENT ELASTOGRAPHY

Liver stiffness measurement using transient elastography (FibroScan; Echosens, Paris, France) was performed routinely from 2015 onward for all eligible patients. A minimum of 10 valid measurements was obtained for each patient, with the median value representative of the liver stiffness. The results were included in the final analysis only if the success rate was >50% combined with an interquartile range-to-liver stiffness ratio of <30%.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 23.0 (IBM Corp). Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-squared test and Fisher's exact test when appropriate. The Mann-Whitney test was used to analyze continuous independent variables with skewed distribution, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to analyze pair-related samples. The cumulative incidence rates of events and survival were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method, with log-rank testing for comparison. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

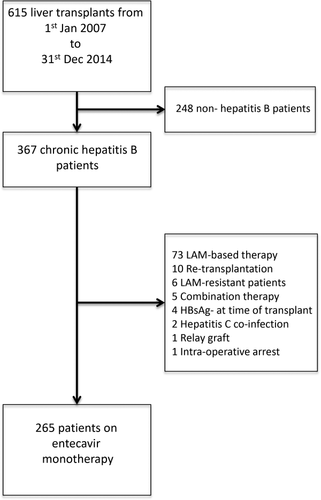

A total of 615 patients underwent liver transplantation from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2014, at The Liver Transplant Center, Queen Mary Hospital (Hong Kong). Of these, 367 were CHB patients, of whom 102 were excluded because of non-ETV-based therapy, presence of LAM-resistant mutations prior to transplantation, retransplantations, hepatitis C coinfection, use of hepatitis B graft, and intraoperative arrest. A total of 265 patients who received ETV monotherapy as their primary antiviral prophylaxis after liver transplantation were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). The median duration of follow-up was 59 months (range 0-108). Two hundred and twenty (83%) were male, with a median age at the time of transplant of 53 years (range 23-68). The proportions of patients receiving deceased and living donor liver transplants were 51% and 49%, respectively. The primary indications for transplant include chronic decompensation in 75 (28%) patients, severe acute flares of CHB in 93 (35%) patients, and HCC in 97 (37%) patients. The basic patient characteristics and laboratory data are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Total number (n) | 265 |

| Gender | |

| Male, n (%) | 220 (83%) |

| Female, n (%) | 45 (17%) |

| Age (years) | 53 (23-68) |

| Follow-up (months) | 59 (0-108) |

| Type of transplant, n (%) | |

| Living donor liver transplant | 130 (49%) |

| Deceased donor liver transplant | 135 (51%) |

| Indication for liver transplant, n (%) | |

| Cirrhosis with liver decompensation | 75 (28%) |

| Acute flare of chronic hepatitis B | 93 (35%) |

| HCC | 97 (37%) |

- Continuous variables are expressed as median (range).

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | 143 (4-886) |

| ALP (U/L) | 113 (20-471) |

| AST (U/L) | 72 (18-3,000) |

| ALT (U/L) | 48 (9-3,000) |

| Albumin (g/L) | 34 (17-54) |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 80 (33-885) |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 20.9 (10.9-82.0) |

| INR | 1.9 (1.0-5.3) |

| MELD score | 23 (6-51) |

| HBV DNA (log IU/mL) | 1.85 (0.78-8.23) |

| HBV DNA distribution at time of transplant | |

| HBV DNA undetectable | 39% |

| HBV DNA ≤4 logs IU/mL | 35% |

| HBV DNA >4-6 logs IU/mL | 15% |

| HBV DNA >6 logs IU/mL | 11% |

- Continuous variables are expressed as median (range).

- Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; INR, international normalized ratio; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

All surviving patients were considered for transient elastography. Of the 265 patients, 217 underwent liver stiffness measurement. In the 48 patients without liver stiffness measurement, 33 had died, 2 had retransplantation, 8 were followed up elsewhere, and 5 had underlying mobility or significant medical comorbidities unrelated to the liver. Of the 217 patients with liver stiffness measurement, 214 had valid measurements, with a median time of acquisition of 50 months posttransplant (range 6-100).

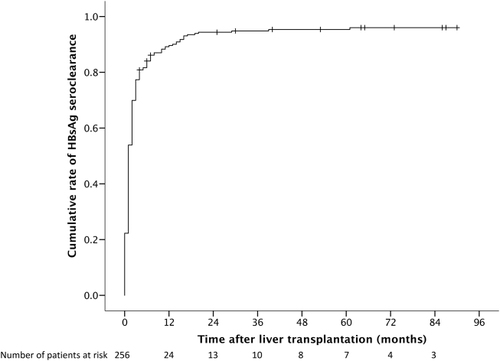

HBsAg

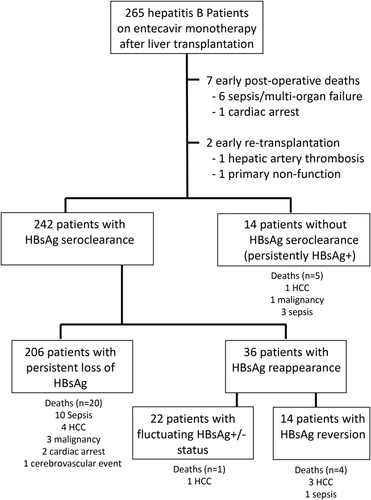

The cumulative rate of HBsAg seroclearance was 77% by 3 months, 90% by 1 year, and 95% by 5 years (see Fig. 2). Nine patients (3%) had no serological testing performed as a result of early postoperative mortality or retransplantation. The majority of HBsAg seroclearance occurred early after transplantation, with only 10% occurring after 1 year posttransplant. Of the 242 patients who had HBsAg seroclearance after transplantation, 206 (85%) were sustained without evidence of HBsAg reappearance. The cumulative rate of HBsAg reappearance was 13% at 3 years after initial HBsAg reappearance, with minimal increase after 3 years. The numbers of patients with persistent, transient, and no HBsAg seroclearance and their outcomes are summarized in Fig. 3.

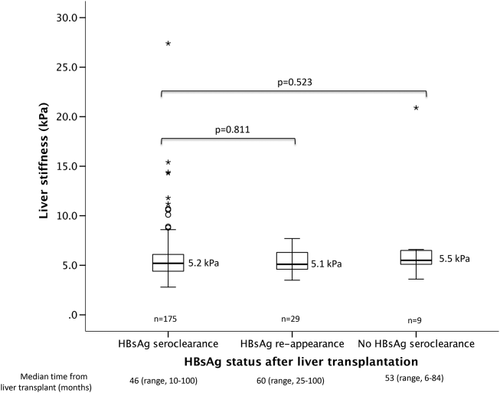

A total of 36 patients had HBsAg reappearance after initial loss of HBsAg. Of these, 22 had fluctuating HBsAg status with episodes of positivity and negativity throughout the follow-up period, and 14 had persistent HBsAg seroreversion. Five out of 36 patients died (4 from HCC recurrence and 1 from aspergillosis). Of the remaining 31 patients, 29 underwent valid transient elastography. There was no significant difference between those patients who had HBsAg reappearance after initial HBsAg loss compared to those who had sustained HBsAg seroclearance (5.1 versus 5.2 kPa, respectively; P = 0.811; Fig. 4).

Fourteen (6%) patients had persistently positive HBsAg without any evidence of seroclearance. None of these patients had any virological rebound. Five patients died of unrelated causes (3 from sepsis/infection, 1 from lymphoma, and 1 from HCC recurrence). Of the remaining 9 patients, 2 had add-on tenofovir early after transplant because of slowly declining HBV DNA and 7 had undetectable HBV DNA with completely normal graft function. There was no significant difference in liver stiffness measurement between those who were persistently positive for HBsAg and those who achieved HBsAg seroclearance and maintained HBsAg negativity (5.5 versus 5.2 kPa respectively; P = 0.523; Fig. 4). Of the 9 patients, all but one had liver stiffness <7.0 kPa, indicating a lack of significant fibrosis. Only 1 had liver stiffness of 20.9 kPa. A liver biopsy performed showed only nonspecific changes without any significant fibrosis, with ultrasonography showing normal graft size and parenchymal echogenicity and with completely normal graft function. The long-term HBsAg negativity rate was durable, with 85% being HBsAg-negative after 1 year posttransplant, extending to 92% at 8 years after transplantation (Fig. 5).

ANTI-HBs ANTIBODY

A total of 108 developed detectable anti-HBs during the follow-up period. This occurred very early within the posttransplant period, with cumulative rates of 31% by 1 month and 40% by 6 months. The rate of anti-HBs development after liver transplant was higher for those receiving grafts from anti-HBs-positive donors compared to those who were anti-HBs-negative (P < 0.001). For those who received grafts from donors who were anti-HBs-positive and anti-HBc-positive, the cumulative rate of anti-HBs development after transplantation at 1 year was 61% compared to 16% for donors who were negative for both (P < 0.001). The majority (83%) who developed detectable anti-HBs had loss of anti-HBs during the follow-up period, with a median time from antibody detection to antibody loss of 4 months (range 0-94). There was no significant difference in the rate of permanent HBsAg loss for those who received a graft from an anti-HBs-positive donor compared to those from an anti-HBs-negative donor (79.9% versus 85.1%, respectively; P = 0.315).

VIRAL LOAD

Of the 265 patients, 253 had available HBV DNA measurements at the time of transplantation. Only 99 (39%) had undetectable HBV DNA at the time of transplant, while 154 (61%) had detectable HBV DNA (Table 2). Of those 154 with detectable HBV DNA, 90 (35%) had HBV DNA ≤4 logs IU/mL, 37 (15%) had HBV DNA >4-6 logs IU/mL, and 27 (11%) had HBV DNA >6 logs IU/mL. The 64 patients with HBV DNA >4 logs IU/mL at the time of transplantation were followed up for a median of 69.5 months compared to 57 months for those with HBV DNA ≤4 logs (P = 0.111). For those with HBV DNA >4 logs IU/mL, 70.3%, 17.2%, and 12.5% had permanent, transient, and no loss of HBsAg, respectively, compared to 83.0%, 13.7%, and 3.3% for those with HBV DNA ≤4 logs IU/mL (P = 0.014). Five patients with HBV DNA >4 logs IU/mL had switch or add-on tenofovir therapy compared to only 1 patient with HBV DNA ≤4 logs IU/mL. There was no significant difference in median liver stiffness for those with HBV DNA >4 logs versus ≤4 logs IU/mL (5.4 versus 5.1 kPa, respectively; P = 0.150) and no difference between the two groups in the proportion of patients with liver stiffness >7.0 kPa (7.0% versus 9.3%, respectively; P = 0.784) and >9.0 kPa (5.3% versus 4.0%, respectively; P = 0.709).

Comparison between those transplanted for severe acute flares and those transplanted for chronic decompensation/HCC showed a significantly shorter median waiting time from listing to transplantation (3 versus 40 days, respectively; P < 0.001) and a significantly higher median HBV DNA at the time of transplant (4.13 versus 0.78 log IU/mL, respectively; P < 0.001).

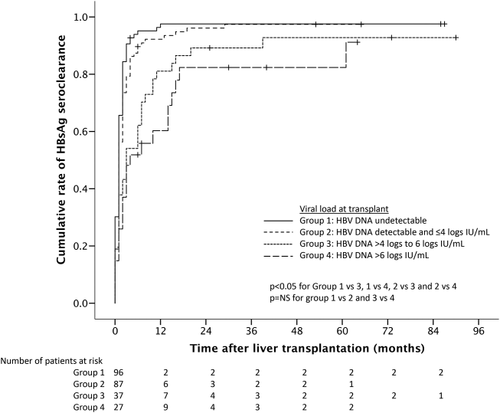

By year 1 posttransplant, 95% had undetectable HBV DNA, reaching almost 100% by year 2 (Fig. 5). The viral suppression was sustainable in the long term with undetectable HBV DNA observed in 100% at year 8 after liver transplantation (Fig. 5). The rate of HBsAg seroclearance was significantly higher for those with HBV DNA ≤4 logs IU/mL compared to those with higher viral loads (Fig. 6). At 1 year posttransplant, the HBsAg seroclearance rates were 98%, 92%, 81%, and 60% for HBV DNA at transplant of undetectable levels, ≤4 logs IU/mL, >4 to 6 logs IU/mL, and over 6 logs IU/mL, respectively (P < 0.001).

HCC

A total of 97 patients had HCC at the time of transplantation and were followed up for a median of 51 months. After transplant, 88.3%, 10.6%, and 1.1% had persistent, transient, and no HBsAg seroclearance, respectively. Seventy-seven patients had liver stiffness measurement performed, and there was no significant difference in liver stiffness between those with and without HCC (5.3 versus 5.2 kPa, respectively; P = 0.488). There was no significant difference between the proportion of HCC and non-HCC patients with liver stiffness >7.0 kPa (6.6% versus 10.2%, respectively; P = 0.372) and >9.0 kPa (5.3% versus 4.4%, respectively; P = 0.747).

There were a total of 13 HCC recurrences. For those with recurrence, there was a higher rate of HBsAg reappearance compared to those without (45.5% versus 7.4%, respectively; P = 0.003). Of the 36 patients with transient loss of HBsAg and with reappearance, 26 did not have HCC at the time of transplant and there was no occurrence of de novo HCC. The remaining 10 patients had HCC at the time of transplant, of whom 6 had HCC recurrence. Transient elastography was performed in only 1 of the 13 recurrences due to earlier deaths, with normal stiffness of 3.6 kPa.

SURVIVAL

Overall survival rates were 93%, 88%, 86%, and 85% at 1, 3, 5, and 9 years, respectively, after liver transplant (Fig. 7). There were a total of 37 deaths during the follow-up period, of which 20 (54%) were due to sepsis/infection, 9 (24%) to HCC recurrence, 3 (8%) to cardiac arrest, 4 (11%) to malignancy, and 1 (3%) to traumatic cerebrovascular event. Two patients required retransplantations within a few weeks due to hepatic artery thrombosis and nonfunctioning graft.

SAFETY

There were no side effects attributable to ETV reported during the follow-up period. There were no deaths attributed to HBV reactivation or from recurrence of HBV-related graft hepatitis. All 265 patients were on ETV monotherapy as primary prophylaxis after liver transplantation. Six (2%) patients had additional or change in their antiviral prophylaxis during their follow-up period, of whom 3 had additional tenofovir add-on therapy and 3 had switch to tenofovir monotherapy. The reasons for adding or switching to tenofovir and the results after these changes are described in Table 3. Two patients had a history of potential LAM resistance, and tenofovir was used as a precaution despite the HBV DNA being undetectable, with HBsAg fluctuating between negative and positive status. The remaining 4 patients had tenofovir as a precaution because of slowly declining HBV DNA after transplantation; the HBV DNA levels were already low at the time of change (≤2.4 log IU/mL). All 6 patients had change in therapy as a precaution, and none of these 6 patients had evidence of virological rebound. The remaining 260 patients were maintained on ETV monotherapy.

| No. |

Baseline HBV DNAHBV DNA |

Switch/Add-On HBV DNA |

Time to Switch/Add-On (Months) |

Rebound | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.74 | Undetectable | 59 | None | Possible history of LAM-R, add-on as precaution |

| 2 | 2.54 | Undetectable | 59 | None | Possible history of LAM-R, switch as precaution |

| 3 | 4.65 | Undetectable | 26 | None | Slow decline, add-on as precaution |

| 4 | 5.34 | 1.59 | 20 | None | Slow decline, switch as precaution |

| 5 | 7.23 | 2.40 | 10 | None | Slow decline, add-on as precaution |

| 6 | 5.12 | 2.08 | 14 | None | Slow decline, switch as precaution |

- HBV DNA measured in log international units per milliliter.

There was a significant increase in median serum creatinine from the time of transplant to 1 year posttransplant (79.0 versus 97.0 μmol/L, respectively; P < 0.001). For those with follow-up to 5 years, there was no significant difference in median serum creatinine levels between 1 and 5 years posttransplant (95.5 versus 96.0 μmol/L, respectively; P = 0.953). Two patients with preexisting chronic renal disease required long-term hemodialysis within 1 year posttransplant, with renal deterioration unrelated to the use of nucleoside analogues.

Discussion

The approval of oral nucleos(t)ide analogues with high barriers to resistance in the last decade has revolutionized CHB treatment, replacing LAM as the first-line therapy.11 Similarly, a changing paradigm in antiviral prophylaxis has been observed for CHB patients after liver transplantation. The main drawback of LAM therapy was its high resistance rate. The combination approach of HBIG and LAM proved to be highly effective at preventing HBV reactivation and was superior to either agent alone.12-14 However, the use of HBIG requires regular parenteral injections, which is costly and inconvenient. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of oral antiviral therapy alone after cessation of limited duration of HBIG.15-17 In 2011, a study in 80 patients using ETV monotherapy alone without the use of HBIG was demonstrated to be effective at preventing HBV reactivation after liver transplantation for CHB-related complications.9 There was no graft loss attributable to HBV recurrence, although the median follow-up was only 26 months. Therefore, the durability of viral suppression, in addition to the long-term outcome, remains unknown.

The current study reported the long-term outcome of ETV monotherapy as antiviral prophylaxis after liver transplantation in a larger cohort, with results for up to 8 years. There was a high rate of HBsAg seroclearance, with a proportion of patients developing transient anti-HBs levels shortly after transplantation. The development of positive anti-HBs is likely the result of passive transfer from the donor given the rapid detectability after transplant, the higher rate observed with anti-HBs-positive donors, and the transient nature.

Importantly, the current long-term study demonstrated that the HBsAg negativity rate and HBV DNA suppression were durable, with an HBsAg-negative rate of 91.7% and an HBV DNA undetectable rate of 100% at 8 years after transplantation. The efficacy of ETV monotherapy was also reflected by the excellent long-term survival at 85% at 9 years after transplantation, without any retransplantation or deaths related to HBV reactivation. Of note, delta infection is exceedingly rare in Hong Kong and has not been observed in the transplant population.

Although approximately 15% of patients remain HBsAg-positive throughout the duration of follow-up, this did not signify HBV reactivation as HBV DNA remained completely suppressed. It also does not signify HBV recurrence as chronically infected patients are rarely able to completely eliminate HBV, even after transplantation. The administration of HBIG in this setting will invariably lead to a higher rate of HBsAg negativity by the formation of immune complexes, thereby evading detection. However, the additional clinical benefit conferred by adding HBIG may be negligible in light of the excellent long-term outcome and survival demonstrated with an HBIG-free regimen in the current study. In addition, liver stiffness measurements did not show any significant differences between those who had durable HBsAg seroclearance compared to those who remained HBsAg-positive after transplantation. This would suggest that there is no increase in significant fibrosis for those who remain HBsAg-positive on the background of undetectable HBV DNA. In a previous histological study of 36 HBsAg-positive patients with undetectable HBV DNA after liver transplantation using oral antiviral therapy only, there was no evidence of HBV infection from the liver biopsies.18 Furthermore, the level of HBsAg for those without HBsAg seroclearance or those with HBsAg reappearance after transplantation has been shown to remain at a very low level.9

Of the 36 patients with HBsAg reappearance, 4 had HCC recurrence, suggesting possible isolated HBsAg production resulting from transcription of integrated HBsAg gene within the tumor tissue in these patients. Indeed, a study in a cohort of HBV-related HCC patients demonstrated the presence of HBsAg using immunohistochemical staining of extrahepatic tumor tissue.19

This study also demonstrated that despite >60% detectable HBV DNA at the time of transplant, a high rate of HBsAg seroclearance and viral suppression can still be achieved. However, higher levels of viral load were significantly associated with a lower rate of HBsAg seroclearance. Similar observations were made in an earlier study with HBIG monotherapy that showed higher rates of recurrence with higher HBV DNA levels, suggesting that high-dose HBIG may not be able to neutralize the high circulating levels of HBsAg.2 With the availability of living donor liver transplantation, those patients transplanted for acute flares had a significantly shorter waiting time, with less time on antiviral therapy and a higher viral load at the time of transplantation compared to those transplanted for chronic decompensation and HCC.

The current study showed that ETV was safe and well tolerated. There were 6 patients who either had additional or a switch to tenofovir therapy as a precaution. Similar to pretransplant patients, a tiny proportion of patients receiving ETV may have primary nonresponse or delayed virological response.20 This highlights the fact that continual monitoring of HBV DNA is needed, and tenofovir can be useful as an alternative or additional agent for those who may harbor the rtM204 mutation or have a slow viral decline. The initial increase at year 1 of serum creatinine that was observed is unlikely due to the effect of ETV and is likely due to multiple factors, including the use of calcineurin inhibitors. Unlike nucleotide analogues such as adefovir and tenofovir, ETV is not known to be directly nephrotoxic. The serum creatinine at the time of transplant may be spuriously low due to advanced liver disease with reduced creatine production, combined with a low skeletal muscle mass. Reassuringly, there was no further decline observed from year 1 to year 5 posttransplant.

In conclusion, long-term ETV monotherapy was highly effective in the prevention of HBV reactivation after liver transplantation for CHB patients, with a durable HBsAg seroclearance rate of 92% and an HBV DNA undetectable rate of 100% at 8 years. This was associated with excellent overall long-term survival of 85% at 9 years posttransplant, without any graft loss or death due to HBV reactivation.