Monotherapy with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for multiple drug-resistant chronic hepatitis B: 3-year trial

Potential conflict of interest: Dr. Lim consults, advises, is on the speakers' bureau, and received grants from Gilead and Bristol-Myers Squibb. He received grants from Novartis. Dr. Byun received grants from Gilead.

A part of this study (2-year results) was presented at the International Liver Congress, Barcelona, Spain, April 15, 2016.

Supported by Gilead Sciences; the Korean National Health Clinical Research project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HC15C3380); the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI14C1061 and HI17C1862); and the Proteogenomic Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Korean government.

Abstract

Combination therapy has been recommended for the treatment of patients harboring multiple drug-resistant hepatitis B virus (HBV). However, we recently demonstrated that monotherapy with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) for 48 weeks displayed noninferior efficacy to TDF plus entecavir (ETV) combination therapy in patients with HBV resistant to multiple drugs, including ETV and adefovir. Nonetheless, whether prolonged TDF monotherapy would be safe and increase the virologic response rate in these patients was unclear. Among 192 patients with HBV-resistance mutations to ETV and/or adefovir, who were randomized to receive TDF monotherapy (n = 95) or TDF/ETV combination therapy (n = 97) for 48 weeks, 189 agreed to continue TDF monotherapy (TDF-TDF group) or to switch to TDF monotherapy (TDF/ETV-TDF group) and 180 (93.8%) completed the 144-week study. Serum HBV DNA <15 IU/mL at week 48, the primary efficacy endpoint, was achieved in 66.3% in the TDF-TDF group and 68.0% in the TDF/ETV-TDF group (P = 0.80). At week 144, the proportion with HBV DNA <15 IU/mL increased to 74.5%, which was significantly higher compared with that at week 48 (P = 0.03), without a significant difference between groups (P = 0.46). By on-treatment analysis, a total of 79.4% had HBV DNA <15 IU/mL at week 144. Transient virologic breakthrough occurred in 6 patients, which was due to poor drug adherence. At week 144, 19 patients who had HBV DNA levels >60 IU/mL qualified for genotypic resistance analysis, and 6 retained some of their baseline resistance mutations of HBV. No patients developed additional resistance mutations throughout the study period. Conclusion: TDF monotherapy was efficacious and safe for up to 144 weeks, providing an increasing rate of virologic response in heavily pretreated patients with multidrug-resistant HBV. (Hepatology 2017;66:772–783).

Abbreviations

-

- ADV

-

- adefovir dipivoxil

-

- ALT

-

- alanine aminotransferase

-

- BMD

-

- bone mineral density

-

- ETV

-

- entecavir

-

- eGFR

-

- estimated glomerular filtration rate

-

- HBeAg

-

- hepatitis B e antigen

-

- HBsAg

-

- hepatitis B surface antigen

-

- HBV

-

- hepatitis B virus

-

- HCC

-

- hepatocellular carcinoma

-

- LAM

-

- lamivudine

-

- NUC

-

- nucleos(t)ide analogue

-

- pol/RT

-

- polymerase/reverse transcriptase domain

-

- TDF

-

- tenofovir disoproxil fumarate

Persistent replication of hepatitis B virus (HBV) is an independent risk factor for disease progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients with chronic hepatitis B.1, 2 By contrast, reducing HBV DNA concentrations to very low or undetectable levels through long-term nucleos(t)ide analogue (NUC) therapy is associated with reduced risk of mortality and HCC.3-5 Nonetheless, eradication of HBV is very rarely achievable, necessitating long-term, almost indefinite, NUC therapy.6, 7

Development of drug-resistant HBV mutants during long-term NUC therapy limits the efficacy of treatment. Patients with persistent drug-resistant HBV viremia are more likely to have hepatitis flares and disease progression and to die than those without drug-resistant HBV.3 Therefore, potent antivirals without the propensity to select for resistance, such as tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and entecavir (ETV), are recommended.8, 9 However, many patients worldwide have developed drug resistance from the widespread use of less potent NUCs, such as lamivudine (LAM) or adefovir dipivoxil (ADV), which have a low genetic barrier to resistance.10 Combination therapy with a nucleoside analogue and a nucleotide analogue is generally recommended for the treatment of patients harboring multidrug-resistant HBV.11

TDF, the oral prodrug of tenofovir, is a nucleotide analogue with potent activity against HBV DNA polymerase, and it was shown to be noninferior to the combination of emtricitabine and TDF in patients with LAM-resistant HBV for up to 240 weeks.12 Further, in our recent randomized trials, we also demonstrated that TDF monotherapy for 48 weeks provided a virologic response comparable to that of TDF plus ETV combination therapy in heavily pretreated patients with HBV resistant to ETV and ADV.13, 14 Nonetheless, the rate of virologic response (serum HBV DNA <15 IU/mL) was suboptimal at 48 weeks of TDF therapy in patients with ETV resistance (71%) and ADV resistance (62%),13, 14 which raised a concern about whether prolonged TDF monotherapy would safely increase the rate of virologic response in these patients. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the safety and efficacy of prolonged TDF monotherapy in patients with ETV-resistant and ADV-resistant HBV for up to 144 weeks as an extension of our two previous trials.

Patients and Methods

STUDY DESIGN

This study was a combined extension trial of two multicenter randomized trials conducted in patients who had persistent HBV viremia and documented genotypic resistance to ETV (rtT184A/C/F/G/I/L/S, rtS202G, and rtM250L/V, in addition to rtM204V/I; ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT01639066) or to ADV (rtA181V/T and/or rtN236T; ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT01639092). After completing 48 weeks of randomized, parallel comparisons of TDF monotherapy (300 mg once daily) versus TDF/ETV combination therapy, patients were eligible to continue TDF monotherapy (TDF-TDF group) or switch to TDF monotherapy (TDF/ETV-TDF group). Study conduct and methods have been described.13, 14 Only methods unique to this extension study are presented here.

The study was conducted in compliance with all regulatory obligations and the institutional review board of each investigational site.

STUDY SUBJECTS

Patients were enrolled from five centers in Korea between September 2012 and August 2013. Patients with chronic hepatitis B (defined as a positive serum hepatitis B surface antigen [HBsAg] test for at least 6 months) were eligible for enrollment if they had serum HBV DNA levels >60 IU/mL at screening, were currently receiving any NUC other than TDF, and were confirmed to have HBV genotypic resistance mutations to ETV (the presence of rtT184A/C/F/G/I/L/S, rtS202G, or rtM250L/V, in addition to rtM204V/I) and/or ADV (rtA181V/T and/or rtN236T). Patients were required to be between 20 and 75 years old and to have serum creatinine levels <1.5 mg/dL. Prior and/or ongoing LAM, ETV, and ADV therapy in any combination was permitted; and prior interferon therapy was allowed if treatment was discontinued at least 12 months before screening. Patients were excluded if they had prior exposure to TDF for more than 1 week, evidence of decompensated liver disease, any malignant neoplasm, or coinfection with hepatitis C, hepatitis D, or human immunodeficiency virus.

EFFICACY AND SAFETY MEASURES

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients who achieved a virologic response (serum HBV DNA <15 IU/mL) at week 48; a predefined follow-up analysis at week 144 is reported here. Secondary efficacy endpoints included the proportion of patients with HBV DNA <15 IU/mL at week 144, the proportion of patients with HBV DNA levels <60 IU/mL, the change in HBV DNA levels from baseline, the proportion of patients with normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and the proportion of patients with hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) loss/seroconversion (HBeAg-positive patients only) and HBsAg loss/seroconversion, at weeks 48 and 144. The incidence of virologic breakthrough (increases in HBV DNA levels ≥1 log10 IU/mL from nadir on two consecutive tests) was evaluated throughout the study period. The probability of developing resistance was evaluated by genotypic analysis for all patients who experienced virologic breakthrough or persistent viremia (i.e., HBV DNA >60 IU/mL) by the last time point of treatment and at weeks 48, 96, and 144.

Adverse events (clinical and laboratory) were assessed throughout the 144 weeks. Glomerular filtration rate was estimated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation as follows; estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR; milliliters per minute per 1.73 m2) = 175 × serum creatinine−1.154 × age−0.203 (× 0.742 if female). Bone mineral density (BMD) measurements of the lumbar spine and femur were determined by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry at baseline and at weeks 48, 96, and 144.

Adherence to study drugs was assessed by counting the number of pills and empty blister packets returned at each visit.

SERUM ASSAYS

Serum HBV DNA levels were measured using a real-time PCR assay (linear dynamic detection range, 15 IU/mL to 1 × 109 IU/mL; Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL). Resistance mutations were determined by restriction fragment mass polymorphism analyses and direct sequencing of the reverse transcriptase region of the HBV polymerase gene (pol/RT). Serum HBsAg was tested quantitatively (Architect assay; Abbott Laboratories; lower limit of detection, 0.05 IU/mL). Serological markers, including antibody to HBsAg, HBeAg, and antibody to HBeAg, were determined using enzyme immunoassays (Abbott Laboratories).

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Efficacy and safety analyses were performed comparing the originally randomized treatment groups, TDF-TDF and TDF/ETV-TDF. The primary efficacy and safety analyses were performed on the full analysis set, which included all patients who were randomized (intention-to-treat analysis). Patients who discontinued the study prior to week 144 for any reason were considered failures for all endpoints after the time of discontinuation, regardless of HBV DNA suppression. The second analysis was an on-treatment analysis that included all patients on study.

Between-group comparisons of continuous or categorical variables were conducted using the t test, analysis of variance, chi-squared test, or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Differences in the proportion of patients who achieved virologic response between week 48 and week 144 were compared with the McNemar test. Predefined subgroup analyses were performed on the baseline viral load and resistance mutations to ADV.

All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 3.0, http://cran.r-project.org/). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

STUDY PATIENTS

A total of 192 patients with HBV resistant to ETV and/or ADV were randomized to receive TDF monotherapy (TDF-TDF group, n = 95) or TDF plus ETV combination therapy (TDF/ETV-TDF group, n = 97) for 48 weeks (Supporting Fig. S1). Among them, 189 completed week 48 and agreed to receive TDF monotherapy for 96 more weeks and 180 (93.8%) completed 144 weeks. Reasons for discontinuing the study included withdrawal of consent (n = 6), adverse events (n = 2), death due to HCC (n = 2), and death by other causes (n = 2). None had virologic breakthrough at dropout.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of treatment groups were comparable at baseline (Table 1). The median age was 51 years, and the population was predominantly male (81.2%). Forty patients (20.8%) had cirrhosis, and 170 patients (88.5%) were HBeAg-positive. The median HBV DNA level was 3.71 log10 IU/mL. All patients had HBV genotype C. Most patients had been exposed to multiple drugs before enrollment, including LAM, telbivudine, ETV, and ADV. The median overall duration of prior NUC treatments was 95 months. Most patients (76.7%) were being treated with various ADV-based combination therapies at baseline.

| Characteristics | Total | TDF-TDF | TDF/ETV-TDF |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 192 | 95 | 97 |

| Agea (years) | 51 (22-70) | 51 (22-68) | 51 (26-70) |

| Male, n (%) | 156 (81.2%) | 74 (77.9%) | 82 (84.5%) |

| ALTa (IU/L) | 32 (11-275) | 32 (12-275) | 32 (11-243) |

| Abnormal ALT, n (%) | 57 (29.7%) | 26 (27.4%) | 31 (32.0%) |

| Abnormal ALT by AASLD criteria, n (%) | 113 (58.9%) | 57 (60.0%) | 56 (57.7%) |

| Bilirubina (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.3-2.5) | 0.8 (0.3-2.5) | 0.9 (0.3-2.5) |

| Albumina (g/dL) | 4.4 (2.8-5.2) | 4.4 (1.6-5.2) | 4.4 (2.8-5.1) |

| INRa | 0.99 (0.85-1.40) | 0.98 (0.85-1.35) | 0.99 (0.85-1.40) |

| Creatininea (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.5-1.4) | 0.9 (0.5-1.4) | 0.9 (0.5-1.4) |

| eGFRa (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 92 (49-142) | 92 (49-143) | 92 (54-139) |

| Phosphatea (mg/dL) | 3.2 (1.7-5.0) | 3.2 (1.7-5.0) | 3.2 (2.0-4.6) |

| Cirrhosis,b n (%) | 40 (20.8%) | 18 (18.9%) | 22 (22.7%) |

| HBsAg levela (log10 IU/mL) | 3.58 (0.35-4.73) | 3.57 (2.16-4.62) | 3.60 (0.35-4.73) |

| HBeAg positivity, n (%) | 170 (88.5%) | 84 (88.4%) | 86 (88.7%) |

| HBV DNAa (log10 IU/mL) | 3.71 (1.78-9.00) | 3.89 (1.78-9.00) | 3.65 (1.98-8.79) |

| HBV genotype C, n (%) | 192 (100%) | 95 (100%) | 97 (100%) |

| NUCs exposed before enrollment,c n (%) | |||

| ETV only | 5 (2.6%) | 3 (3.2%) | 2 (2.1%) |

| ADV only | 2 (1.0%) | 0 | 2 (2.1%) |

| LAM and ETV | 16 (8.3%) | 7 (7.4%) | 9 (9.3%) |

| LdT and ETV | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 1 (1.0%) |

| ADV and LAM | 15 (7.8%) | 7 (7.4%) | 8 (8.2%) |

| ADV and ETV | 11 (5.7%) | 6 (6.3%) | 5 (5.2%) |

| ADV, LAM, and LdT | 6 (3.1%) | 2 (2.1%) | 4 (4.1%) |

| ADV, LAM, and ETV | 112 (58.3%) | 55 (57.9%) | 57 (58.8%) |

| ADV, LAM, LdT, and ETV | 24 (12.5%) | 15 (15.8%) | 9 (9.3%) |

| Overall duration of NUC treatments before enrollmenta (months) | 95 (11-273) | 99 (11-273) | 93 (11-194) |

| Ongoing treatment at baseline, n (%) | |||

| ADV | 11 (5.7%) | 4 (4.2%) | 7 (7.2%) |

| ETV | 34 (17.7%) | 18 (18.9%) | 16 (16.5%) |

| ADV+LAM | 23 (12.0%) | 12 (12.6%) | 11 (11.3%) |

| ADV+LdT | 15 (7.8%) | 10 (10.5%) | 5 (5.2%) |

| ADV+ETV | 109 (56.8%) | 51 (53.7%) | 58 (59.8%) |

| Response to ongoing treatments at baseline, n (%) | |||

| Partial virologic response | 165 (85.9%) | 79 (83.2%) | 86 (88.7%) |

| Virologic breakthrough | 27 (14.1%) | 16 (16.8%) | 11 (11.3%) |

| HBV-resistance mutations,d n (%) | |||

| to LAM and ETV | 90 (46.9%) | 45 (47.4%) | 45 (46.4%) |

| to ADV only | 15 (7.8%) | 9 (9.5%) | 6 (6.2%) |

| to LAM and ADV | 36 (18.8%) | 21 (22.1%) | 15 (15.5%) |

| to LAM, ETV, and ADV | 51 (26.6%) | 20 (21.1%) | 31 (32.0%) |

| ADV-resistance mutations,d n (%) | 102 (53.1%) | 50 (52.6%) | 52 (53.6%) |

| Single (rtA181T/V or rtN236T) | 68 (35.4%) | 35 (36.8%) | 33 (34.0%) |

| Double (rtA181T/V and rtN236T) | 34 (17.7%) | 15 (15.8%) | 19 (19.6%) |

| Prior treatment with interferon, n (%) | 8 (4.2%) | 5 (5.3%) | 3 (3.1%) |

- a Median (range).

- b Cirrhosis was diagnosed by ultrasonography with identification of liver surface nodularity and splenomegaly.

- c NUCs that were used >6 months.

- d Genotypic resistance test was performed by both direct sequencing and restriction fragment mass polymorphism analyses. HBV-resistance mutation to LAM was defined as rtM204V/I with or without rtL180M. HBV-resistance mutation to ETV was defined as rtT184A/C/F/G/I/L/S, rtS202G, or rtM250L/V, in addition to rtM204V/I. HBV-resistance mutation to ADV was defined as rtA181T/V and/or rtN236T. ADV, 10 mg/day; ETV, 1 mg/day; LAM, 100 mg/day; TDF, 300 mg/day.

- Abbreviations: AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; INR, international normalized ratio; LdT, telbivudine.

All patients had HBV-resistance mutations to ETV (rtL180M, rtT184A/C/F/G/I/L/S, rtS202G, and rtM250L/V, in addition to rtM204V/I) and/or ADV (rtA181T/V, rtN236T, and rtA181T/V+rtN236T) in various combinations.

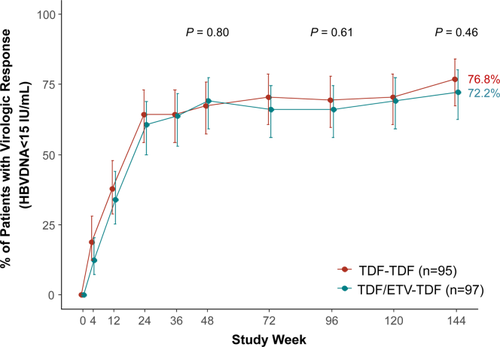

VIROLOGIC RESPONSE

By intention-to-treat analysis, no significant difference in the proportion of patients who achieved a virologic response at week 48 was observed between the TDF-TDF and TDF/ETV-TDF groups (Table 2 and Fig. 1; Supporting Fig. S2). Of the patients who were randomized to TDF alone, 66.3% (63/95) had HBV DNA levels <15 IU/mL at week 48 compared with 68.0% (66/97) of those receiving TDF/ETV (P = 0.80). At week 144, the proportion of patients with HBV DNA levels <15 IU/mL increased to 74.5% (143/192), which was significantly higher compared with that at week 48 (P = 0.03), with no significant difference between groups (76.8% versus 72.2%; P = 0.46).

| Endpoint | At Week 48 | At Week 144 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total (N = 192) |

TDF-TDF (n = 95) |

TDF/ETV-TDF (n = 97) |

P |

Total (N = 192) |

TDF-TDF (n = 95) |

TDF/ETV-TDF (n = 97) |

P | |

| HBV DNA <15 IU/mL, n (%) | 129 (67.2%) | 63 (66.3%) | 66 (68.0%) | 0.80 | 143 (74.5%) | 73 (76.8%) | 70 (72.2%) | 0.46 |

| HBV DNA <60 IU/mL, n (%) | 155 (80.7%) | 74 (77.9%) | 81 (83.5%) | 0.32 | 161 (83.9%) | 79 (83.2%) | 82 (84.5%) | 0.80 |

| HBV DNA <15 IU/mL, on-treatment, n (%) | 129/189 (68.3%) | 63/94 (67.0%) | 66/95 (69.5%) | 0.72 | 143/180 (79.4%) | 73/90 (81.1%) | 70/90 (77.8%) | 0.58 |

| HBV DNA <60 IU/mL, on-treatment, n (%) | 155/189 (82.0%) | 74/94 (78.7%) | 81/95 (85.3%) | 0.24 | 161/180 (89.4%) | 79/90 (87.8%) | 82/90 (91.1%) | 0.47 |

| HBV DNA change from baselinea (log10 IU/mL) | –3.42 ± 1.55 | –3.33 ± 1.74 | –3.51 ± 1.34 | 0.43 | –3.67 ± 1.60 | –3.70 ± 1.77 | –3.65 ± 1.43 | 0.86 |

| Residual HBV DNA levelb (log10 IU/mL) | 1.93 (1.20-7.99) | 2.08 (1.30-7.99) | 1.72 (1.20-3.04) | 0.05 | 1.81 (1.23-2.75) | 1.94 (1.34-2.75) | 1.66 (1.23-2.40) | 0.05 |

| Virologic breakthroughc | 2 (1.0%) | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0.99 | 6 (3.1%) | 4 (4.2%) | 2 (2.1%) | 0.39 |

| ALTd (IU/L) | 28 (8-122) | 26 (8-114) | 32 (8-122) | 0.23 | 26 (10-243) | 25 (12-243) | 28 (10-193) | 0.57 |

| ALT change from baselined (IU/L) | –1 (–246 to 75) | –1 (–246 to 62) | –1 (–211 to 75) | 0.93 | –2 (–256 to 210) | –2 (–256 to 210) | –1 (–219 to 35) | 0.25 |

| ALT normal, n (%) | 140 (72.9%) | 72 (75.8%) | 68 (70.1%) | 0.38 | 148 (77.1%) | 74 (77.9%) | 74 (76.3%) | 0.79 |

| ALT normal by AASLD criteria, n (%) | 98 (51.0%) | 55 (57.9%) | 43 (44.3%) | 0.60 | 104 (54.2%) | 54 (56.8%) | 50 (51.5%) | 0.46 |

| ALT normalization,e n/N (%) | 32/57 (56.1%) | 16/26 (61.5%) | 16/31 (51.6%) | 0.45 | 35/57 (61.4%) | 17/26 (65.4%) | 18/31 (58.1%) | 0.57 |

| ALT normalization by AASLD criteria,e n/N (%) | 35/113 (31.0%) | 23/57 (40.4%) | 12/56 (21.4%) | 0.03 | 45/113 (39.8%) | 23/57 (40.4%) | 22/56 (39.3%) | 0.91 |

| HBeAg seroclearance,f n/N (%) | 19/170 (11.2%) | 12/84 (14.3%) | 7/86 (8.1%) | 0.20 | 26/170 (15.3%) | 17/84 (20.2%) | 9/86 (10.5%) | 0.56 |

| HBeAg seroconversion,f n/N (%) | 5/170 (2.9%) | 2/84 (2.4%) | 3/86 (3.5%) | 0.31 | 7/170 (4.1%) | 6/84 (7.1%) | 1/86 (1.2%) | 0.50 |

| HBsAg seroclearance, n | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | — |

| HBsAg change from baselinea (log10 IU/mL) | –0.24 ± 0.45 | –0.27 ± 0.52 | –0.21 ± 0.37 | 0.34 | –0.41 ± 0.47 | –0.45 ± 0.52 | –0.36 ± 0.41 | 0.21 |

| HBsAg level decrease from baseline ≥1 log10 IU/mL, n (%) | 15 (7.8%) | 10 (10.5%) | 5 (5.2%) | 0.17 | 23 (12.0%) | 15 (15.8%) | 8 (8.2%) | 0.11 |

- Intention-to-treat population, missing equals failure.

- a Mean ± standard deviation.

- b Median (range) in patients who had HBV DNA detectable at week 48 and week 144, respectively.

- c Cumulative number of patients with virologic breakthrough. Virologic breakthrough was defined as an increase in HBV DNA levels ≥1 log10 IU/mL from nadir on two consecutive tests.

- d Median (range).

- e Among those with abnormal ALT at baseline.

- f Among those HBeAg-positive at baseline.

- Abbreviation: AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

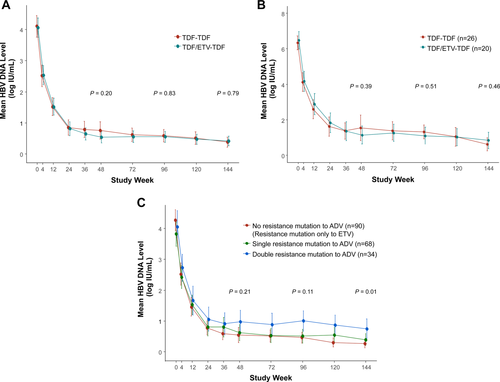

In the on-treatment analysis, the proportion of patients who achieved HBV DNA levels <15 IU/mL was not significantly different between the TDF-TDF and TDF/ETV-TDF groups at week 48 (67.0% versus 69.5%; P = 0.72) and at week 144 (81.1% versus 77.8%; P = 0.58; Table 2; Supporting Fig. S3). At week 144, the proportion of patients with HBV DNA levels <15 IU/mL increased to 79.4% (143/180), which was significantly higher compared with that at week 48 (P < 0.001). The proportion of patients who had HBV DNA levels <60 IU/mL at week 144 was 87.8% in the TDF-TDF group and 91.1% in the TDF/ETV-TDF group (P = 0.47; Table 2; Supporting Fig. S4). The mean change from baseline in serum HBV DNA levels was not significantly different between the TDF-TDF and TDF/ETV-TDF groups at week 48 (−3.33 log10 IU/mL versus −3.51 log10 IU/mL; P = 0.43) and at week 144 (−3.70 log10 IU/mL versus −3.65 log10 IU/mL; P = 0.86; Table 2 and Fig. 2A). Among 180 patients who completed week 144, 37 had HBV DNA detectable at week 144, with median levels of 1.94 log10 IU/mL in the TDF-TDF group and 1.66 log10 IU/mL in the TDF/ETV-TDF group (P = 0.05).

VIROLOGIC RESPONSE IN PATIENT SUBGROUPS

Among patients who had a high viral load (HBV DNA levels >5 log10 IU/mL) at baseline, the mean HBV DNA levels significantly decreased from baseline without significant difference between the TDF-TDF (n = 26) and TDF/ETV-TDF (n = 20) groups at week 48 (−4.79 log10 IU/mL versus −5.34 log10 IU/mL, P = 0.27) and at week 144 (−5.79 log10 IU/mL versus −5.63 log10 IU/mL, P = 0.68; Fig. 2B). The proportion of patients with HBV DNA levels <15 IU/mL was also comparable between the two groups at week 48 (42.3% versus 45.0%, P = 0.86) and at week 144 (61.5% versus 60.0%, P = 0.92; Supporting Fig. S5).

Because there was no significant difference in virologic response between the TDF-TDF and TDF/ETV-TDF groups throughout the study period, we combined the data of the two treatment groups for the further subgroup analyses. When classified according to baseline ADV-resistance mutations, the three groups of patients, i.e., no resistance mutation to ADV, single-resistance mutation to ADV (either rtA181T/V or rtN236T), and double-resistance mutations to ADV (both rtA181T/V and rtN236T), had significantly different mean HBV DNA levels at week 144 (0.27 log10 IU/mL versus 0.40 log10 IU/mL versus 0.75 log10 IU/mL, P = 0.01; Fig. 2C). The three groups were also significantly different in the proportion of patients with HBV DNA <15 IU/mL at week 144 (82.2% [74/90] versus 72.1% [49/68] versus 58.8% [20/34], P = 0.02; Supporting Fig. S6). For the proportion of patients with HBV DNA <60 IU/mL, the three groups also showed a gradual nonsignificant difference throughout the study period (87.8% [79/90] versus 82.4% [56/68] versus 76.5% [26/34] at week 144, P = 0.29; Supporting Fig. S7).

BIOCHEMICAL AND SEROLOGIC RESPONSES

The proportion of patients with normal ALT levels was not significantly different between the TDF-TDF and TDF/ETV-TDF groups at week 48 (75.8% versus 70.1%; P = 0.38) and at week 144 (77.9% versus 76.3%; P = 0.79; Table 2).

The proportion of HBeAg-positive patients who achieved HBeAg seroconversion was low, with no significant difference between the two groups at week 48 (2.4% versus 3.5%; P = 0.31) and at week 144 (7.1% versus 1.2%; P = 0.50; Table 2).

None of the patients achieved HBsAg loss or seroconversion. The median change in serum HBsAg levels from baseline was –0.45 log10 IU/mL and –0.36 log10 IU/mL at week 144 in TDF-TDF and TDF/ETV-TDF groups, respectively, with no significant difference between groups (P = 0.21; Table 2; Supporting Fig. S8). The number of patients who showed an HBsAg level decrease from baseline ≥1 log10 IU/mL was 15 (15.8%) and 8 (8.2%) in the TDF-TDF and TDF/ETV-TDF groups, respectively (P = 0.11; Table 2).

VIROLOGIC BREAKTHROUGH AND RESISTANCE SURVEILLANCE

Over the 144-week treatment period, 4 patients in the TDF-TDF group and 2 patients in the TDF/ETV-TDF group experienced virologic breakthrough (P = 0.39; Table 2); all cases were associated with decreased adherence to study medication (<80%) and were transient, requiring no treatment modification. During virologic breakthrough, some of the baseline resistance mutations, but no additional substitutions, were detected in pol/RT in the patients (Table 3).

| Patient No. | Treatment Group | Week at Test | Treatment at Test |

HBV DNA Level at Test (log10 IU/mL) |

HBV Mutation at Baseline | HBV Mutation at Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with virologic breakthrough | ||||||

| 2064 | TDF-TDF | 36 | TDF | 8.04 | rtM204V/I+rtL180M+rtA181T | rtA181T |

| 1001 | TDF-TDF | 48 | TDF | 7.99 | rtM204V+rtL180M+rtM250V | rtM204V+rtL180M+rtM250V |

| 2014 | TDF-TDF | 120 | TDF | 5.36 | rtM204V/I+rtL180M+rtA181T/V+rtM202G | rtA181T |

| 1062 | TDF-TDF | 120 | TDF | 2.62 | rtM204V+rtL180M+rtM250V | rtM204V+rtL180M+rtM250V |

| 2045 | TDF/ETV-TDF | 36 | TDF/ETV | 2.00 | rtM204V/I+rtL180M+rtA181T/V+rtN236T+rtT184L | rtM204V/I+rtL180M+ rtT184L |

| 2015 | TDF/ETV-TDF | 96 | TDF | 2.59 | rtM204V/I+rtL180M+rtA181T/V+rtN236T | none |

| Patients with HBV DNA >60 IU/mL at discontinuation | ||||||

| 1001 | TDF-TDF | 96 | TDF | 2.68 | rtM204V+rtL180M+rtM250V | rtM204V+rtL180M+rtM250V |

| 2098 | TDF/ETV-TDF | 60 | TDF | 2.84 | rtM204V/I+rtL180M+rtA181T/V+rtM202G | rtL180M+rtM202G |

| Patients with HBV DNA >60 IU/mL at week 144 | ||||||

| 1062 | TDF-TDF | 144 | TDF | 2.40 | rtL180M+rtM204V+rtM250V | L180M+rtM204V+rtM250V |

| 2014 | TDF-TDF | 144 | TDF | 2.20 | rtL180M+rtM204VI+rtA181T+rtS202G | A181T |

| 2041 | TDF-TDF | 144 | TDF | 2.40 | rtM204VI+rtA181TV+rtN236T | A181T+rtN236T |

| 2050 | TDF-TDF | 144 | TDF | 2.70 | rtA181TV+rtN236T+rtM250V | A181T+rtN236T |

| 2064 | TDF-TDF | 144 | TDF | 2.75 | rtL180M+rtM204VI+rtA181T | A181T |

| 1045 | TDF/ETV-TDF | 144 | TDF | 2.32 | rtL180M+rtM204V+rtS202G | L180M+rtM204V+rtS202G |

- Genotypic resistance test was performed by both direct sequencing and restriction fragment mass polymorphism analyses.

Among the 12 patients who discontinued the study, two had HBV DNA >60 IU/mL at the last time point of treatment and qualified for genotypic resistance analysis. At the last time point, no additional substitutions were detected in the pol/RT gene compared to baseline (Table 3).

At week 144, 11 and 8 patients in the TDF-TDF and TDF/ETV-TDF groups, respectively, had HBV DNA levels >60 IU/mL (P = 0.47) and qualified for genotypic resistance analysis. Among them, 5 patients in the TDF-TDF group and 1 patient in the TDF/ETV-TDF group had at least one detectable HBV resistance mutation at week 144 (P = 0.21; Table 3), all of which were present at baseline. No patients developed additional substitutions in pol/RT compared to baseline.

SAFETY

Safety profiles throughout the 144-week study period were similar between treatment groups, with comparable frequencies of adverse events and serious adverse events (Table 4). None of the serious adverse events was judged to be related to the study medication. HCC was diagnosed in 3 patients in the TDF-TDF group and in 4 patients in the TDF/ETV-TDF group. Two patients in the TDF-TDF group died due to sudden cardiac arrest and sleep apnea at weeks 98 and 122, respectively. Transient on-treatment ALT flares (increase of ALT >5 × the upper limit of normal range) were observed in three patients in each group, which were not associated with an increase in HBV DNA levels.

| Adverse Event Categorya | Total | TDF-TDF | TDF/ETV-TDF |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 192 | 95 | 97 |

| Any adverse event | 120 (62.5%) | 62 (65.3%) | 58 (59.8%) |

| Serious adverse events | 33 (17.2%) | 18 (18.9%) | 15 (15.5%) |

| HCC | 7 (3.6%) | 3 (3.2%) | 4 (4.1%) |

| Deaths | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| ALT flareb | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Discontinuation due to adverse eventc | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Dose reduction due to adverse eventd | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| eGFR <50 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Serum phosphate <2.0 mg/dL | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Bone fracture | 3 | 2 | 1 |

- a Patients are counted only once for each category.

- b ALT flares (increase of ALT >5 times the upper limit of the normal range) were transient and not associated with an increase in HBV DNA levels.

- c Epigastric pain and headache, which were judged to be related to TDF and ETV, respectively.

- d TDF dose was reduced due to transient elevation of creatinine by the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which was not suspected to be associated with TDF treatment.

eGFR significantly increased from baseline at week 144 (3.14 mL/min/1.73 m2, P = 0.002) without a significant difference between the TDF-TDF and TDF/ETV-TDF groups (P = 0.55; Supporting Fig. S9). The mean change in serum phosphate level at week 144 was minimal (−0.01 mg/dL; P = 0.80) and comparable between the groups (P = 0.86; Supporting Fig. S10).

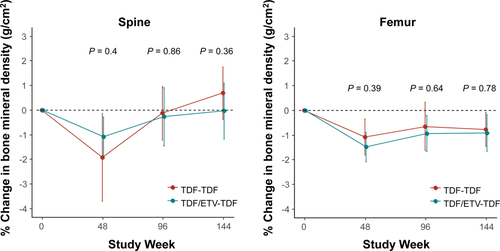

Baseline dual-energy X-ray absorptiometric assessments for the spine and femur revealed 15 patients (7.8%) with evidence of osteoporosis (T scores below −2.5) and 66 patients (34.4%) with evidence of osteopenia (T score range, −1 to above −2.5). At week 144, the proportion of patients with osteoporosis and osteopenia was 12 (6.7%) and 64 (35.6%), respectively, which was not significantly different when compared with baseline (P = 0.41). The mean percent change in BMD (grams per square centimeter) at week 144 from baseline was 0.33% at the spine (P = 0.42) and −0.84% at the femur (P = 0.002), without a significant difference between the TDF-TDF and TDF/ETV-TDF groups (P = 0.20 for spine and P = 0.77 for femur; Fig. 3). The mean change in FRAX score at week 144 from baseline was 0.16 for major osteoporotic score (P = 0.04) and 0.09 for hip fracture score (P = 0.14; Supporting Fig. S11). Bone fractures were reported in 2 patients (at weeks 112 and 136) in the TDF-TDF group and in 1 patient (at week 72) in the TDF/ETV-TDF group, all of which were associated with trauma.

Discussion

This 3-year trial in heavily pretreated patients with HBV resistant to multiple drugs, including LAM, ETV, and/or ADV, showed that TDF monotherapy was safe and gradually increased the rate of virologic response. In the initial 48-week parallel comparison, TDF monotherapy demonstrated a noninferior virologic response rate compared to the combined therapy with TDF plus ETV. Both the extension of TDF monotherapy and the switch from TDF/ETV combination to TDF monotherapy after 48 weeks showed effective viral suppression in the patients for up to 144 weeks. TDF monotherapy was associated with no additional emergence but rather a marked reduction in detectable resistance mutations of HBV. Few patients experienced transient virologic breakthrough during treatment, which were associated with low adherence to the drug. The treatment was well tolerated, and the overall patient retention rate was high (93.8%) at 144 weeks.

Our patients had persistent viremia during a median 95 months of overall treatments with various NUCs before entering this study. They had developed multidrug-resistant HBV through sequential accumulation of resistance mutations to LAM, ETV, and/or ADV. Treatment options for these patients with multidrug-resistant HBV are severely limited. ETV monotherapy should not be a treatment option for these patients because most of the patients were resistant to LAM and ETV.15 Furthermore, 45.3% of our patients had HBV clones with LAM-resistant and ADV-resistant mutations that are known to reduce the susceptibility to the combination of LAM and ADV by >50-fold.16 Our previous study clinically demonstrated that the combination of LAM and ADV exerts virtually no antiviral effect in patients with multidrug-resistant HBV.17

Because ETV may have minimal antiviral efficacy in the presence of HBV mutants resistant to LAM and ETV, treatment responses to TDF plus ETV combination therapy would theoretically be mediated by TDF alone, which was clinically demonstrated by the initial phase of our study.13 Furthermore, our finding that 83.9% of patients with TDF monotherapy had HBV DNA <60 IU/mL at week 144 was similar to the results of a recent single-arm trial with TDF+ETV in patients with previous NUC treatment failure, which showed the proportion of patients with HBV DNA <50 IU/mL to be 85% at week 96.18 Our data are in accordance with previous in vitro studies which showed that HBV strains harboring ETV resistance–associated substitutions, rtM204V/I, rtT184, rtS202, and/or rtM250, exhibit no cross-resistance to tenofovir.19 However, HBV strains expressing ADV resistance–associated substitutions, rtA181T/V and/or rtN236T, demonstrate reduced susceptibility to tenofovir, ranging from 2.9-fold to 10-fold of that of the wild-type virus.20 Nonetheless, TDF concentrations achieved in vivo are high enough to suppress the replication of HBV variants, preventing the accumulation of additional substitutions.21

The short-term rate of virologic response (HBV DNA <15 IU/mL) with TDF monotherapy and TDF/ETV combination therapy was suboptimal (66.3% and 68%, respectively, at week 48). These results were concerning because persistently replicating HBV clones would be more likely to develop additional resistance mutations.22 However, the increasing rate of virologic response and no emergence of resistance mutations during long-term TDF monotherapy are reassuring. Although the rate of virologic response at week 48 in our patients was lower compared to those reported in previous clinical trials of TDF in treatment-naive or LAM-resistant patients,23, 24 our data became similar with previous studies12, 25 upon long-term TDF treatment.

The majority (88.5%) of our patients were HBeAg-positive at baseline, and the influence of host factors in achieving virologic response was suspected by the considerably low HBeAg seroconversion rate (4.1%) at week 144 compared to those of previous reports in treatment-naive patients treated with TDF (21%) for 48 weeks.24 These findings suggested that the duration of TDF treatment required to achieve virologic response would be prolonged particularly in patients with multidrug-resistant HBV variants. Even for patients with virologic response, the rate of HBeAg seroconversion and decrease in HBsAg levels during the treatment were minimal, which necessitates long-term indefinite treatment for the patients.

The most worrisome group of patients during TDF monotherapy was those with double ADV-resistance mutations (both rtA181T/V and rtN236T). In vitro susceptibility data showed that double-mutation (rtA181T/V and rtN236T) resulted in a 7-fold to 10-fold reduction in sensitivity to tenofovir compared to that of the single rtA181T mutant.20, 26 In fact, by subgroup analysis, the patients with double ADV-resistance mutations showed a significantly lower rate of virologic response (HBV DNA <15 IU/mL) throughout the study period compared to those with no or single ADV-resistant mutations. However, most of the patients maintained a very low level of HBV DNA (median 71 IU/mL at week 144), and there was a considerable reduction in detectable resistance mutations during the study period.

Treatment with TDF was well tolerated, consistent with other long-term trials of TDF in treatment-naive and LAM-resistant patients.12, 25 Mean eGFR showed a small but significant increase from baseline at week 144, which may be associated with the fact that almost all patients at enrollment were taking ADV, which frequently causes renal impairment.27, 28 The decrease in spine and femur BMD reached a nadir at week 48. Interestingly, spine BMD was subsequently restored, while femur BMD stabilized up to 144 weeks. These results are consistent with those observed during TDF therapy in LAM-resistant patients over 240 weeks.12 Bone fractures that occurred in three patients were associated with trauma; therefore, their clinical significance is unknown. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation was not a protocol requirement of our study.

This study may have some limitations as an open-label single-arm extension study. Because there was no difference in the two arms during the first 48 weeks when patients were randomized to TDF+ETV versus TDF, extending the comparison of the two groups over 48 weeks was unlikely to show a difference. Although not comparative post–week 48, these long-term data may provide important information about the safety and efficacy of prolonged TDF monotherapy in patients with multidrug-resistant HBV. Second, the predominant population had relatively low HBV DNA levels at baseline. This may be associated with the decreased replicative fitness of HBV with multiple mutations21 and the preceding partially effective combination therapies.29, 30 However, the subgroup of patients with high viral load at baseline also showed persistent and significant decreases in HBV DNA over the study period. Third, all of the patients included in this study had genotype C HBV, which may indicate some limitations in the generalization of the results. However, no evidence has been suggested that HBV genotype may have an impact upon the antiviral efficacy of TDF.23, 24 Fourth, the markers of proximal tubular dysfunction, such as urine retinol-binding protein to creatinine ratio and urine beta-2-microglobulin to creatinine ratio, were not assessed in this study. Because long-term treatment with TDF could be associated with proximal tubulopathy, subclinical tubular injury should be assessed in future studies. Lastly, liver biopsies were not taken and noninvasive markers of hepatic fibrosis were not assessed in this study, so we were unable to draw any conclusions about the impact of long-term treatment on fibrosis stage.

In conclusion, TDF monotherapy for up to 144 weeks provided an increasing rate of virologic response in heavily pretreated patients with multidrug-resistant HBV. Very few patients experienced virologic breakthrough, no additional resistance mutations emerged, and the treatment was generally well tolerated. Given the necessity of long-term indefinite NUC treatment to maintain viral suppression and taking into consideration the lower potential risk of adverse events, lower cost, and noninferior antiviral efficacy compared with TDF/ETV combination therapy, our data suggest that TDF monotherapy may be a proper long-term treatment option for patients with multidrug-resistant HBV.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Seungbong Han for his help with statistical analyses; YunJeong In, Sinae Kim, Hyang Ki Lee, and Bomi Park for their help with data collection; the Academic Research Office and the Clinical Trial Center affiliated with Asan Medical Center for their operational oversight of the trial; and Ms. Vanessa Topping for critically reviewing the paper. None received compensation for their work.

REFERENCES

Author names in bold denote shared co-first authorship.