The role of hepatic resection in the treatment of hepatocellular cancer

Potential conflict of interest: Dr. Park is on the speakers' bureau for and received grants from Bayer. He consults for Taiho. Dr. Sherman consults for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and Bayer.

The BRIDGE database and data collection were funded by Bristol-Meyers Squibb. Centers were provided with funds for entry of data. The analysis of the data reported here and the preparation of the manuscript were not funded by any source or company.

Abstract

Current guidelines recommend surgical resection as the primary treatment for a single hepatocellular cancer (HCC) with Child's A cirrhosis, normal serum bilirubin, and no clinically significant portal hypertension. We determined how frequently guidelines were followed and whether straying from them impacted survival. BRIDGE is a multiregional cohort study including HCC patients diagnosed between January 1, 2005 and June 30, 2011. A total of 8,656 patients from 20 sites were classified into four groups: (A) 718 ideal resection candidates who were resected; (B) 144 ideal resection candidates who were not resected; (C) 1,624 nonideal resection candidates who were resected; and (D) 6,170 nonideal resection candidates who were not resected. Median follow-up was 27 months. Log-rank and Cox's regression analyses were conducted to determine differences between groups and variables associated with survival. Multivariate analysis of all ideal candidates for resection (A+B) revealed a higher risk of mortality with treatments other than resection. For all resected patients (A+C), portal hypertension and bilirubin >1 mg/dL were not associated with mortality. For all patients who were not ideal candidates for resection (C+D), resection was associated with better survival, compared to embolization and “other” treatments, but was inferior to ablation and transplantation. Conclusions: The majority of patients undergoing resection would not be considered ideal candidates based on current guidelines. Not resecting ideal candidates was associated with higher mortality. The study suggests that selection criteria for resection may be modestly expanded without compromising outcomes, and that some nonideal candidates may still potentially benefit from resection over other treatment modalities. (Hepatology 2015;62:440–451

Abbreviations

-

- AASLD

-

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

-

- BCLC

-

- Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

-

- CSPH

-

- clinically significant portal hypertension

-

- EASL

-

- European Association for Study of the Liver

-

- HCC

-

- hepatocellular carcinoma

-

- HVPG

-

- hepatic vein portal gradient

-

- PH

-

- portal hypertension

-

- RFA

-

- radiofrequency ablation

-

- WHO

-

- World Health Organization

The current European Association for Study of the Liver (EASL) and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) guidelines recommend resection as the primary treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients with a single tumor, Child class A liver function with total bilirubin ≤1mg/dL, no evidence of clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH), and excellent performance status.1, 2 The criteria also require patients to have no evidence of extrahepatic disease or invasion of portal or hepatic veins on imaging.

These guidelines are essentially based on a study from 1999 that drew its conclusions from 77 patients undergoing hepatic resection for HCC.3 In addition, the guidelines are centered on the concept of who would be “ideal” candidates for resection, thus yielding the highest survival for surgery as a treatment modality. The guidelines do not base their recommendations on what treatment modality yields the best outcome in a particular individual. Thus, whereas a patient may not be an ideal candidate for resection, surgery may still yield better outcomes for that individual than the alternative treatment modality proposed by the current guidelines.

It is unclear what proportion of HCC patients are actually treated according to these guidelines in real-world practice. Two Italian studies looking at adherence to HCC guidelines have found that the majority of patients with HCC are not treated according to AASLD/EASL guidelines.4, 5 A multinational study looking specifically at resection of HCC had a population comprised of 36% Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) B and 14% BCLC C patients.6

In addition, multiple studies have tried to show that expanding the guidelines to include patients with multiple tumors, portal hypertension (PH), or Child's B liver function will not have an adverse effect on outcome.7-14 All of these studies have included a relatively small number of patients and based their conclusions on a lack of significance in univariate log-rank or multivariate Cox's analyses.

- In what proportion of cases are the guidelines followed?

- Does straying from the guidelines result in lower survival?

- What factors are associated with mortality after resection and can inclusion criteria be expanded without increasing mortality?

- How does resection compare to other treatment modalities in patients who do not meet criteria for resection based on current guidelines?

Patients and Methods

The global HCC BRIDGE study is a multiregional longitudinal cohort trial including patients newly diagnosed with HCC between January 1, 2005, and June 30, 2011, who are receiving treatment for HCC at sites in the Asia-Pacific, European, and North American regions. The study recruited patients from 42 sites and followed them until death or the data cut-off date of March 1, 2012. Centers were provided funds for data entry by Bristol-Meyers Squibb. This analysis of the data and preparation of the manuscript received no funding from any source. The treatments employed were at the discretion of the centers. Requests to participate in the study were sent to all centers.

During the initial data collection, centers were audited after enrolment of 15 patients and again after 50 patients to ensure accurate data entry. During the audit, source data were reviewed and compared to entries in the BRIDGE database. All staging was entirely based on imaging data from multiphase contrast enhanced computer-assisted tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging. Pathological data were not used in this analysis. Study coordinators were educated and repeatedly reminded that World Health Organization (WHO) performance status was to be determined based on tumor-related symptoms.

Ablation included both alcohol ablation as well as radiofrequency ablation (RFA). Embolization included transarterial chemoembolization as well as bland embolization. “Other” therapies included locoregional treatments, such as hepatic artery chemoinfusion without embolization, yttrium-90 radioembolization, and external beam radiation, as well as systemic treatments, such as sorafenib, erlotinib, bevacizumab, and adriamycin.

All treatments for each patient were recorded. For the purposes of this analysis, patients with multiple types of treatments were categorized as the treatment modality with the highest likelihood of cure as follows:

Transplantation → Resection → Ablation → Embolization → Other.

- Ideal candidates resected. These patients were required to have a single tumor of any size on imaging with no evidence of extrahepatic spread and no evidence of invasion of the hepatic or portal vein branches. They also were required to have no evidence of CSPH defined as either splenomegaly, varices, or ascites on imaging or platelet count <100,000/μL. In addition, patients were required to have a WHO performance status of 0. Finally, all patients were required to have Child's A liver function with total bilirubin ≤1 mg/dL. All patients in this group underwent resection. Separate analyses were also run, defining PH as both platelet count <100,000/μL and the presence of splenomegaly, varices, or ascites on imaging.

- Ideal candidates not resected. This group was comprised of patients who met criteria for group A, but were treated with a modality other than resection.

- Nonideal candidates resected. This group was comprised of patients who underwent resection, but did not meet the criteria for group A.

- Nonideal candidates not resected. This group consisted of patients who did not meet criteria for group A and were treated with a modality other than resection.

The primary endpoint studied was survival. Survival was calculated using Kaplan-Meier's method, and groups were compared using the log-rank test for univariate analyses. Multivariate analyses were conducted with step-down Cox's proportional hazard regression models. Variables entered into the model included ones that have been repeatedly shown to correlate with survival in HCC patients, those found significant on univariate analysis, as well as those that were significantly different among the groups included in the model.

- All patients who were ideal candidates for resection—groups A+B.

- All patients who were resected—groups A+C.

- All patients who were not ideal candidates for resection—groups C+D.

Results

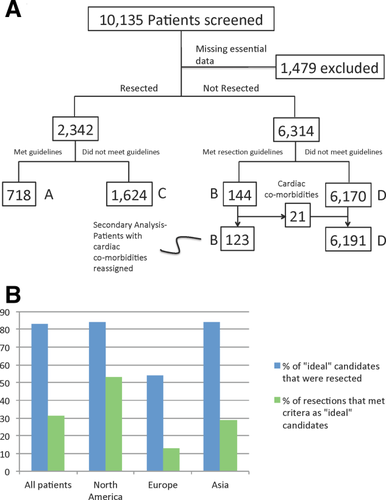

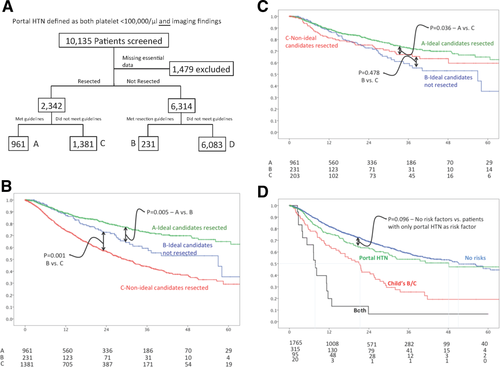

Of the 42 centers enrolling patients, 20 agreed to submit data for inclusion in this study. Of the 10,135 patients, 1,479 were missing essential data that would not allow them to be properly categorized into any of the four groups and were excluded from the analysis. Figure 1A demonstrates the distribution of the patients. The majority of the patients (5,886; 68%) were enrolled from Asian centers, followed by 1,472 (17%) from North American centers, and 1,298 (15%) from European centers.

Flowchart of patients included within the study (A). Adherence to AASLD/EASL criteria by region (B).

Patient demographics and clinical data are summarized in Table 1. Median follow-up of patients was 27 months. There were 3,605 deaths during follow-up. There were a total of 82 perioperative deaths within 90 days of surgery among all of the resected patients (groups A+C). The 90-day perioperative mortality rate was significantly lower among ideal candidates (group A) than among nonideal candidates (group C; 9 of 718 [1.2%] vs. 73 of 1,624 [4.5%]; P < 0.001). However, the rate of morbidity causing prolongation of hospital stay was similar for ideal (group A, 7%) and nonideal candidates (group C, 8%) undergoing resection (P = 0.734).

| Variable n (%) | A Ideal Candidates Resected (n = 718) | B Ideal Candidates Not Resected (n = 144) | C Nonideal Candidates Resected (n = 1,624) | D Nonideal Candidates Not Resected (n = 6,170) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 55 (13.4) | 62(12.9) | 55 (13.0) | 59(12.6) |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 55 (45-65) | 63 (54-73) | 55 (45-64) | 59 (51-68) |

| Range | 19-90 | 24-88 | 18-85 | 18-91 |

| Gender (male, %) | 603 (84) | 120 (83) | 1,327 (82) | 4,970 (81) |

| Liver disease (%) | ||||

| None | 64 (9) | 19 (13) | 155 (10) | 401 (6) |

| HBV | 501 (70) | 67 (47) | 1,043 (64) | 3,066 (50) |

| HCV | 78 (11) | 35 (24) | 281 (17) | 1,357 (22) |

| Alcohol | 24 (3) | 13 (9) | 63 (4) | 580 (9) |

| Other | 22 (3) | 9 (6) | 37 (2) | 756 (12) |

| Missing: 85 | 29 (4) | 1 (1) | 45 (3) | 10 (0.1) |

| Comorbidities (%) | ||||

| Cardiovascular | 51 (7) | 21 (15) | 169 (10) | 849 (14) |

| Missing: 349 | 13 (2) | 0 | 44 (3) | 292 (5) |

| Diabetes | 110 (15) | 29 (20) | 230 (14) | 1,375 (22) |

| Missing: 296 | 14 (2) | 0 | 47 (3) | 235 (4) |

| Hypertension | 191 (27) | 56 (39) | 395 (24) | 1,878 (30) |

| Missing: 190 | 9 (1) | 0 | 36 (2) | 145(2) |

| Pulmonary | 29 (5) | 10 (7) | 196 (12) | 683 (11) |

| Missing: 378 | 11 (1) | 11(8) | 48 (3) | 308 (5) |

| Renal | 29 (4) | 8 (6) | 84 (5) | 367 (6) |

| Missing: 445 | 16 (2) | 10 (7) | 59 (4) | 360 (6) |

| Tumor size, cm, mean (SD) | 5.5 (3.4) | 4.7 (3.4) | 6.0 (3.6) | 5.6 (4.1) |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 4.6 (3.0-7.2) | 3.7 (2.2-6.0) | 5.0 (3.2-8.0) | 4.1 (2.4-8.0) |

| Range | 1.0-22.0 | 1.0-20.0 | 0.9-20.0 | 0.7-28.0 |

| Missing: 761 (%) | 8 (1) | 6 (4) | 102 (6) | 645 (10) |

| Single tumor <2 cm (%) | 86 (12) | 28 (19) | 101 (6) | 659 (11) |

| Missing: 761 | 8 (1) | 6 (4) | 102 (6) | 645 (10) |

| Multiple tumors (%) | 0 | 0 | 425 (26) | 2,526 (41) |

| Missing: 392 | 0 | 0 | 50 (3) | 342 (6) |

| Gross invasion (%) | 0 | 0 | 191 (12) | 587 (10) |

| Missing: 161 | 0 | 0 | 20 (2) | 141 (3) |

| Extrahepatic (%) | 0 | 0 | 215 (13) | 995 (16) |

| Missing: 995 | 0 | 0 | 24 (2) | 971 (16) |

| AFP, ng/mL, mean (SD) | 5,503 (20,549) | 3,916 (25,765) | 12,009 (114,531) | 12,142 (170,871) |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 36 (5-672) | 10 (4.8-98) | 64 (7-1,210) | 64 (10.0-944.5) |

| Range | 0.6-178,518 | 0.7-248,750 | 0.5-3,011,250 | 0.6-12,223,000 |

| Missing: 849 (%) | 46 (6) | 17 (12) | 121 (7) | 665 (11) |

| AFP >400 ng/mL (%) | 253 (35) | 31 (21) | 517 (32) | 1,797 (29) |

| Bilirubin mg/dL, mean (SD) | 0.67 (0.19) | 0.69 (0.19) | 1.04 (1.20) | 1.34 (1.81) |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 0.68 (0.50-0.81) | 0.70 (0.55-0.84) | 0.85 (0.6-1.2) | 0.99 (0.70-1.46) |

| Range | 0.2-1.0 | 0.2-1.0 | 1.0-7.8 | 0.1-43.2 |

| Missing: 340 (%) | 0 | 0 | 29 (2) | 311 (5) |

| Creatinine mg/dL, mean (SD) | 0.95 (0.44) | 0.96 (0.58) | 0.90 (0.29) | 1.12 (0.52) |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 0.90 (0.80-1.03) | 0.87 (0.74-1.01) | 0.89 (0.76-01.00) | 1.00 (1.00-1.10) |

| Range | 0.4—8.4 | 0.4-6.8 | 0.1-4.7 | 0.5-12.6 |

| Missing: 611 (%) | 0 | 8 (6) | 55 (3) | 548 (9) |

| INR, mean (SD) | 1.03 (0.09) | 1.05 (0.11) | 1.07 (0.16) | 1.15 (0.34) |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 1.02 (0.98-1.10) | 1.00 (1.00-1.10) | 1.05 (0.99-1.11) | 1.10 (1.02-1.20) |

| Range | 0.8-1.6 | 0.8-1.7 | 0.7-3.7 | 0.8-21.1 |

| Missing: 710 (%) | 0 | 0 | 58 (4) | 652 (11) |

| Albumin g/dL, mean (SD) | 4.2 (0.4) | 4.0 (0.4) | 4.0 (0.5) | 3.8 (2.2) |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 4.2 (4.0-4.5) | 4.1 (3.8-4.4) | 4.1 (3.7-4.4) | 3.8 (3.4-4.1) |

| Range | 3.5-6.8 | 3.0-4.9 | 1.0-7.8 | 1.2-5.7 |

| Missing: 490 (%) | 0 | 0 | 87 (5) | 403 (7) |

| Platelet ×1,000/µL, mean (SD) | 196 (66) | 175 (61) | 170 (93) | 139 (85) |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 181 (147-230) | 162 (121-214) | 153 (103-215) | 126 (82-189) |

| Range | 101-656 | 100-380 | 11-850 | 4-507 |

| Missing: 439 (%) | 0 | 0 | 68 (4) | 371 (6) |

| MELD, mean (SD) | 7.5 (1.68) | 7.7 (2.22) | 8.2 (2.33) | 9.7 (3.39) |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 7.5 (6.4-7.9) | 7.4 (6.4-8.3) | 7.5 (6.4-8.8) | 8.8 (7.5-10.9) |

| Range | 6-27 | 6-25 | 6-37 | 6-43 |

| Missing: 934 (%) | 0 | 8 (6) | 89 (5) | 837 (13) |

| Child's Class (%) | ||||

| A | 718 (100) | 144 (100) | 1,388 (85) | 4,219 (68) |

| B | 0 | 0 | 113 (7) | 981 (16) |

| C | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.1) | 95 (2) |

| Missing: 996 | 0 | 0 | 121 (8) | 875 (14) |

| PH (%) | 0 | 0 | 595 (37) | 3,507 (57) |

| Missing: 231 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 231 (4) |

| Varices/splenomegaly | 0 | 0 | 347 (21) | 2,262 (37) |

| imaging (%) | 0 | 0 | 68 | 261 |

| Missing: 329 | ||||

| WHO performance status (%) | ||||

| 0 | 718 (100) | 144 (100) | 772 (48) | 535 (9) |

| 1-4 | 0 | 0 | 798 (49) | 5,142 (83) |

| Missing: 549 | 0 | 0 | 56 (3) | 493 (8) |

| BCLC stage (%) | ||||

| A | 718 (100) | 144 (100) | 448 (28) | 317 (5) |

| B | 0 | 0 | 110 (7) | 40 (1) |

| C | 0 | 0 | 969 (60) | 5,213 (84) |

| D | 0 | 0 | 41 (3) | 173 (3) |

| Missing: 483 | 0 | 0 | 56 (4) | 427 (7) |

| Treatments (%) | ||||

| Resection | 718 (100) | 0 | 1,624 (100) | 0 |

| Ablation | 0 | 68 (47) | 0 | 1,917 (31) |

| Transplant | 0 | 9 (6) | 0 | 515 (8) |

| Embolization | 0 | 61 (42) | 0 | 3,569 (57) |

| Others | 0 | 6 (4) | 0 | 169 (3) |

- Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; INR, international normalized ratio; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

In What Proportion of Cases Are the Guidelines for Resection Followed?

Figure 1B demonstrates that, overall, more than 80% of patients who met criteria as ideal candidates were treated with resection. However, only one third of patients undergoing resection met criteria as appropriate candidates. These proportions varied considerably among the three different regions contributing patients.

The most common area in which people strayed from the guidelines was by inclusion of patients with a performance status >0, followed by resection of patients with PH (Table 1).

1 Does Straying From Guidelines Result in Lower Survival?

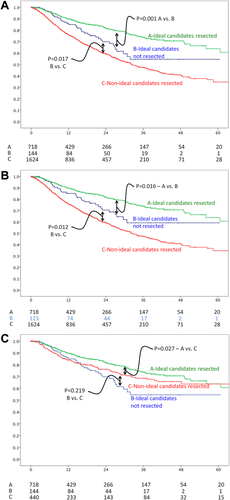

Median survival was not reached for group A; the 3- and 5-year survival rates were 74% and 65%. Group B also did not reach median survival and had 3- and 5-year survivals of 55% and 55%. The median survival for group C was 32.4 months, with 3- and 5-year survivals of 47% and 35% (Fig. 2A).

Survival curves of patients stratified by whether they met AASLD/EASL criteria for resection and type of treatment used. All patients (A). Patients with cardiac comorbidities in group B removed (B). Including only BCLC A patients (C).

It is possible that some patients in group B were not resected because of significant comorbidities. To help address this issue, the 21 patients originally included in group B who had cardiac comorbidities were reassigned to group D and survival was reexamined; there was no appreciable change in outcomes (Fig. 2B).

Group C included patients with tumors at more advanced stages; thus, lead-time bias might explain the decreased survival of this group. To help address this issue, survival was compared among the three groups including only the patients with BCLC stage A tumors. While the outcomes for groups A and B remained unchanged, survival for group C improved appreciably, but remained significantly lower than group A (Fig. 2C).

Multivariate analysis of all ideal candidates for resection (groups A+B) revealed that treatments other than resection were associated with a nearly 2-fold increase in risk of mortality (Table 2).

| Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All ideal candidates for resection (groups A+ B), n = 862 | |||

| Age >70 years | 1.068 | 0.655-1.740 | 0.792 |

| Cardiac comorbidity | 1.158 | 0.655-2.134 | 0.655 |

| AFP >400 ng/mL | 1.566 | 1.085-2.261 | 0.017 |

| Treatment other than resection | 2.068 | 1.349-3.170 | <0.001 |

| Tumor size >3 cm | 3.041 | 1.781-5.193 | <0.001 |

| All resected patients (groups A+C), n = 2,342: PH defined as presence of either imaging findings (splenomegaly, varices, and ascites) or platelet count <100,000/μL | |||

| Age >70 years | 0.984 | 0.755-1.281 | 0.902 |

| PH | 1.170 | 0.959-1.427 | 0.123 |

| Multiple tumors | 1.278 | 1.036-1.576 | 0.022 |

| AFP >400 ng/mL | 1.445 | 1.207-1.730 | <0.001 |

| WHO performance >0 | 1.503 | 1.375-1.644 | <0.001 |

| Extrahepatic tumor | 1.513 | 1.167-1.961 | 0.002 |

| Gross vascular Invasion | 1.783 | 1.373-2.315 | <0.001 |

| Tumor size >3 cm | 1.839 | 1.482-2.415 | <0.001 |

| Child's B or C (only 2 patients Child's C) | 1.923 | 1.446-2.558 | <0.001 |

| All resected patients (groups A+C), n = 2,342: PH defined as presence of both imaging findings (splenomegaly, varices, and ascites) and platelet count <100,000/μL | |||

| Age >70 years | 1.083 | 0.832-1.410 | 0.555 |

| PH | 1.237 | 0.973-1.571 | 0.082 |

| Multiple tumors | 1.346 | 1.095-1.654 | 0.005 |

| AFP >400 ng/mL | 1.435 | 1.198-1.719 | <0.001 |

| WHO performance >0 | 2.300 | 1.923-2.750 | <0.001 |

| Extrahepatic tumor | 1.558 | 1.209-2.008 | <0.001 |

| Gross vascular Invasion | 1.759 | 1.357-2.280 | <0.001 |

| Tumor size >3 cm | 1.817 | 1.425-2.316 | <0.001 |

| Child's B or C(only 2 patients Child's C) | 1.750 | 1.311-2.337 | <0.001 |

| All nonideal patients (groups C+D), n = 7,794 | |||

| Age >70 years | 1.314 | 1.175-1.470 | <0.001 |

| Multiple tumors | 1.0256 | 0.967-1.154 | 0.226 |

| PH | 1.109 | 1.013-1.215 | 0.026 |

| Gross vascular invasion | 1.353 | 1.198-1.528 | <0.001 |

| AFP >400 ng/mL | 1.4216 | 1.292-1.551 | <0.001 |

| Extrahepatic tumor | 1.563 | 1.408-1.735 | <0.001 |

| Child' class (reference = A) | |||

| B | 1.581 | 1.419-1.763 | <0.001 |

| C | 1.855 | 1.299-2.648 | <0.001 |

| Tumor size >3 cm | 1.728 | 1.543-1.963 | <0.001 |

| WHO performance >0 | 2.158 | 1.858-2.507 | <0.001 |

| Treatment (reference = resection) | |||

| Embolization | 1.257 | 1.109-1.429 | <0.001 |

| Ablation | 0.843 | 0.722-0.981 | 0.029 |

| Transplant | 0.189 | 0.133-0.271 | <0.001 |

| Other | 1.782 | 1.334-2.383 | <0.001 |

- Abbreviation: AFP, alpha-fetoprotein.

2 What Factors Are Associated With Mortality After Resection and Can Inclusion Criteria Be Expanded Without Increasing Mortality?

Multivariate analysis of all patients undergoing resection (groups A+C) confirmed that most factors typically thought to be correlated with survival after resection were indeed significantly associated with mortality (Table 2). However, in those undergoing resection, PH alone, defined as the presence of either varices, splenomegaly, or platelet count <100,000/μL, but excluding those with ascites, was not associated with an appreciable decrease in survival either on uni- or multivariate analyses (Table 2; Fig. 3A). In patients with Child's A liver disease undergoing resection, platelet count ranged from 11,000 to 817,000/μL, with only 38 patients having a platelet count <50,000/μL.

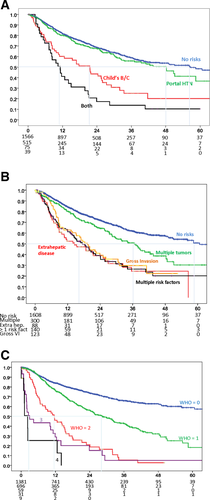

Survival for patients undergoing resection stratified by liver function (A), tumor characteristics (B), and WHO performance status (C). Abbreviation: HTN, hypertension.

Expansion of criteria to include more-severe liver dysfunction (Fig. 3A), advanced tumor characteristics (Fig. 3B), or compromised performance status (Fig. 3C) was associated with a significant detrimental effect on survival.

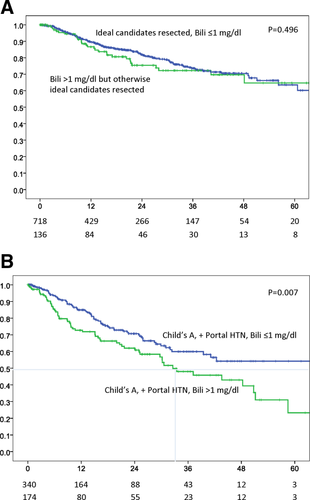

Resection of otherwise ideal candidates, but with total bilirubin over 1 mg/dL, did not have an appreciable impact on survival. The range for total bilirubin in this group was 0.2-2.2 mg/dL, with only 8 patients having total bilirubin >2 mg/dL. Figure 4A shows that, in patients who were otherwise ideal candidates for resection, a total bilirubin cutoff of 1 mg/dL had no correlation with survival. However, if the criteria were slightly expanded to also include patients with PH, then a total bilirubin cutoff of 1 mg/dL played a more discriminatory role (Fig. 4B). Thus, either PH alone or elevated total bilirubin alone had minimal effects on survival, but the presence of both was detrimental.

Survival for ideal candidates undergoing resection stratified by total bilirubin (Bili) cutoff at 1 mg/dL (A). Survival of Child's A patients with PH undergoing resection stratified by total bilirubin cutoff at 1 mg/dL (B). Abbreviation: HTN, hypertension.

A total of 3,103 patients were found to have PH when defined as the presence of both platelet count <100,000/μL as well as imaging findings of splenomegaly, varices, or ascites (missing = 439). The patient flow diagram and results of univariate analyses of survival when defining PH as both the presence of imaging findings and platelet count <100,000/μL are displayed in Fig. 5. Likewise, the results of the multivariate analysis of all resected patients (groups A+C) using this definition of PH are listed in Table 2. There was no meaningful difference in outcomes when using the varying definitions of PH. Median survival after resection for patients with PH who were otherwise ideal candidates was 48 months, irrespective of which definition of PH was used.

Figures based on a definition of PH that required both platelet count <100,000/μL and imaging findings of PH (varices, splenomegaly, or ascites). Flowchart of patients included within the study (A). Survival curves of patients stratified by whether they met AASLD/EASL criteria for resection and type of treatment used. All patients (B). Including only BCLC A patients (C). Survival for patients undergoing resection stratified by liver function (D). Abbreviation: HTN, hypertension.

3 How Does Resection Compare to Other Treatment Modalities in Patients Who Do Not Meet Criteria for Resection Based on Current Guidelines?

Multivariate analysis of all patients who were not ideal candidates for resection (groups C+D) revealed that age >70 years along with the typical tumor characteristics and markers of liver function correlated significantly with mortality (Table 2). However, the presence of multiple tumors was not significantly associated with survival in these patients. Multivariate analysis of this same group of patients was conducted, substituting BCLC class for its individual components, Child's class, gross vascular invasion, and performance status. BCLC stage was independently associated with outcome, but the other results remained unchanged (Table 3).

| Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age >70 years | 1.2237 | 1.119-1.369 | <0.001 |

| Multiple tumors | 1.034 | 0.954-1.119 | 0.416 |

| PH | 1.156 | 1.068-1.2751 | <0.001 |

| AFP >400 ng/mL | 1.515 | 1.398-1.642 | <0.001 |

| Tumor size >3 cm | 1.770 | 1.597-1.961 | <0.001 |

| BCLC stage (reference = A) | |||

| B | 1.431 | 1.039-2.019 | 0.039 |

| C | 2.4319 | 1.905-2.823 | <0.001 |

| D | 5.612 | 4.272-7.371 | <0.001 |

| Treatment (reference = resection) | |||

| Embolization | 1.431 | 1.271-1.611 | <0.001 |

| Ablation | 0.849 | 0.737-0.979 | 0.022 |

| Transplant | 0.195 | 0.141-0.272 | <0.001 |

| Other | 1.784 | 1.358-2.344 | <0.001 |

- Groups C+D, n = 7,794, with BCLC stage in place of Child's class, gross vascular invasion, extrahepatic disease, and performance status.

- Abbreviation: AFP, alpha-fetoprotein.

In these patients, none of whom met criteria as ideal candidates for resection, surgery was associated with lower mortality, when compared to embolization and “other” treatments when controlling for variables that significantly impact survival of HCC patients. However, surgery fared worse than ablation and transplantation in the same population on the multivariate analysis.

Discussion

The vast majority of patients with HCC who meet the EASL/AASLD criteria for resection are treated with surgery. However, it seems that the majority of patients, roughly two thirds, of those undergoing resection do not meet these criteria. It seems that the most common areas where clinicians stray from the current recommendations are by inclusion of patients with a performance status >0 and inclusion of patients with PH.

It would appear that the EASL/AASLD guidelines function well in fulfilling the role for which they were designed, identifying those who will have the best outcomes after resection. In fact, median survival was not reached in ideal patients undergoing hepatic resection. In addition, it seems that straying from EASL/AASLD guidelines for resection, either by resecting nonideal candidates or denying surgery to ideal ones, was associated with a significant decrease in median survival.

Expansion of criteria along the lines of tumor characteristics, liver function, and performance status was associated with a significantly lower survival, even when limiting analysis to BCLC stage A patients. Likewise, subjecting patients who were ideal candidates for resection to a treatment other than hepatectomy was also associated with a 2-fold increase in risk of death, even when taking into account the presence of cardiac comorbidities.

Our analyses did reveal that there may be modest room for expansion of criteria for resection without any appreciable compromise in survival. We found that patients with Child's A liver disease and moderate PH had essentially the same survival after resection as those without PH. It is very important to point out that our definition of CSPH, platelet count <100,000/μL or presence of splenomegaly and/or varices on imaging, is different than the one used by EASL/AASLD guidelines, with hepatic vein portal gradient (HVPG) ≥10 mmHg.2 However, data are emerging that there is, in fact, good correlation between HVPG and platelet count as well as with imaging findings of PH.15

Many, if not most, centers do not routinely perform venous pressure measurements and rely instead on the universally available surrogates of platelet count, splenomegaly, and varices to determine the presence and degree of PH. In fact, of the 13 referral centers represented by the authors in this article, only one routinely measures HVPG before hepatectomy for HCC. Thus, it seems that the current EASL/AASLD recommendations are based on a definition of PH that is not used by a large proportion of centers treating HCC. Perhaps future versions of EASL/AASLD guidelines can incorporate these more widely used, noninvasive methods for assessing PH.

Whereas it seems that many centers are already offering hepatectomy to such patients, formally expanding resection criteria to include those with moderate PH, with a limit of platelet count above 50,000/μL and without ascites, would increase the pool of ideal candidates by approximately 60%. It is difficult to comment on expansion beyond this limit owing to such a small number of patients with platelet count below this level in our cohort. These results were consistent across two separate definitions of PH, one defining PH as the presence of either imaging findings of PH or platelet count <100,000/μL whereas the second definition required the presence of both criteria.

A recent meta-analysis by Berzigotti et al. also looked at the role of PH in the outcomes after resection of HCC, but drew a very different conclusion.16 They found PH as significantly associated with mortality after hepatic resection. The definition of PH used in the study was slightly different than the ones used here. In addition, the Berzigotti et al. study was a meta-analysis spanning 17 years whereas the study reported here is based on individual patient data over a much shorter, more contemporary period. Whereas some of the differences in the conclusions can be attributed to differences in definition and study design, it is clear that the role of PH in outcomes after resection of HCC remains a topic of debate.

We also discovered that, in otherwise ideal candidates, a bilirubin cutoff of 1 mg/dL resulted in no appreciable difference in survival after resection. Again, formal expansion of criteria to include patients with mild elevation of bilirubin up to 2 mg/dL would allow for approximately 25% more patients to undergo resection without any loss in long-term outcome. Again, our data do not allow us to comment on expansion beyond this cutoff.

However, it seems that, in the context of PH, a bilirubin cutoff of 1 mg/dL does have the ability to stratify patients in terms of survival after resection. Thus, whereas expansion along each variable by itself, in otherwise ideal resection candidates, did not worsen outcomes after surgery in our study, the combination of the two does seem to yield significantly lower survival.

Another point on which to caution readers is regarding the lack of data on the extent of resection. Thus, it is possible that patients with PH or elevated bilirubin had more-limited resections than those without. We simply do not know. However, we must keep in mind that the current guidelines do not allow for even limited resections in such patients. The data from the BRIDGE study clearly demonstrate that safe resection with excellent outcomes is possible for patients with moderate PH or for those with slightly elevated bilirubin, but not both. Unfortunately, BRIDGE does not allow us to define the extent of a safe resection. Clearly, clinical judgment will be paramount in selecting these patients for surgery.

A far more complex issue than which patients will achieve the best outcomes with resection is the question of which treatment modality would be best to use for patients who are not considered ideal candidates for hepatic surgery. The current guidelines are based on the principle of selecting candidates who will achieve the best results with surgical resection, not on selecting the treatment that yields the best results in a particular patient. Thus, whereas a patient may not be an ideal candidate for resection, surgery may still yield the best survival of all the available treatment strategies (Tables 2 and 3). Unfortunately, our data did not allow us to identify the characteristics of these patients that might benefit from surgery.

Our multivariate analysis of over 7,600 nonideal patients (groups C+D) seemed to support the majority of the currently endorsed treatment algorithm. Those patients who are not ideal candidates for hepatic resection are better served by transplantation or ablation. In fact, transplantation was associated with a 5-fold decrease in mortality, compared to hepatectomy, in patients that did not meet AASLD/EASL criteria for resection. Though it true that this was not examined on an intention-to-treat basis, the inclusion of dropouts is unlikely to completely eliminate such a large hazard-ratio benefit. Nevertheless, our results show that the applicability of transplant is quite limited, given that transplantation accounted for only 7% of treatments in this group of patients.

The relative roles of resection and ablation as first-line treatments have been debated, even among HCC patients who would meet AASLD/EASL criteria for surgery. Three randomized trials have provided conflicting results.17-19 Again, our study seems to suggest that hepatic resection is the best choice in such patients, corroborating the findings of a large cohort study recently published from the Japanese nation-wide survey.20 However, our study also finds that nonideal surgical candidates may be better served with ablation, rather than resection, and that ablation seems to be a much more widely applied treatment modality, compared to transplantation, for this group of patients.

A more unexpected finding was that resection of such nonideal patients yielded better outcomes than embolization and “other” treatments. These findings will undoubtedly lead to significant debate, but are consistent with some previously published studies supporting resection over embolization.21-23 More important, a recent randomized trial comparing resection with arterial embolization for patients with BCLC B HCC found a significant survival advantage with surgery.24 These findings will certainly bring into question the role of transarterial chemoembolization in treatment of patients with BCLC stage B tumors.

There are some obvious shortcomings of this study that must be acknowledged. Perhaps the most limiting deficiency is the short follow-up of 27 months. This results in the survival data being reliable only to approximately 36 months, after which less than 10% of the population remains at risk. As a result, conclusions regarding long-term survival are not possible. Nevertheless, the large number of patients allows us to reach robust conclusions regarding intermediate outcomes. Another limitation was the lack of a uniform treatment algorithm used across the centers. However, this particular aspect of the study does allow us to compare similar patients that were treated with different modalities at different institutions. Finally, there was no uniform standard technique used for the various treatment modalities at the various centers. For instance, whereas one center may use drug-eluting beads for embolization, another may still be using gelatin foam and lipiodol. There is no easy way to surmount this particular limitation other than relying on the very large sample size to overcome the heterogeneity of technique within each of the various treatments used. As with any large database study, it is impossible to determine exactly how certain treatment decisions were made. Though we have attempted to correct for this to the best of our abilities by running a separate analysis excluding patients with cardiac comorbidities, it is certainly possible that patients were assigned to a particular treatment for reasons not obvious from review of the data.

In summary, our analysis of over 8,500 patients undergoing treatment for HCC yielded important insights into the role of hepatic resection. It appears that, though a relatively rare event, approximately 20% of candidates who meet current EASL/AASLD criteria for resection are denied surgery, and this course of action is associated with a 2-fold increase in mortality. A much more common practice is to offer surgery to patients beyond the recommended criteria. In fact, the majority of patients in all regions undergoing resection did not meet AASLD/EASL criteria. Our study suggests that the current AASLD/EASL criteria might be expanded to include patients with either moderate PH or slightly elevated total bilirubin >1 mg/dL, but not both, without any appreciable increase in mortality. However, expansion of criteria along other lines, such as tumor characteristics, liver function, and performance status, is associated with significantly lower survival. Finally, for patients who do not meet AASLD/EASL criteria for surgery, resection may still associated with longer survival, when compared to embolization and “other” treatments, and shorter survival, in comparison to ablation and transplantation, when controlling for other relevant factors.