Divergent adaptation of hepatitis C virus genotypes 1 and 3 to human leukocyte antigen–restricted immune pressure†

Potential conflict of interest: Dr. McCaughan advises Roche and Schering-Plough. Dr. Gunthard advises and received grants from Gilead and Jansen Cilag. He also received grants from Merck. Dr. Mallal is a consultant for, advises, and is on the speakers' bureau of GlaxoSmithKline. He also advises MSD.

Abstract

Many hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections worldwide are with the genotype 1 and 3 strains of the virus. Cellular immune responses are known to be important in the containment of HCV genotype 1 infection, and many genotype 1 T cell targets (epitopes) that are presented by host human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) have been identified. In contrast, there is almost no information known about the equivalent responses to genotype 3. Immune escape mechanisms used by HCV include the evolution of viral polymorphisms (adaptations) that abrogate this host–viral interaction. Evidence of HCV adaptation to HLA-restricted immune pressure on HCV can be observed at the population level as viral polymorphisms associated with specific HLA types. To evaluate the escape patterns of HCV genotypes 1 and 3, we assessed the associations between viral polymorphisms and specific HLA types from 187 individuals with genotype 1a and 136 individuals with genotype 3a infection. We identified 51 HLA-associated viral polymorphisms (32 for genotype 1a and 19 for genotype 3a). Of these putative viral adaptation sites, six fell within previously published epitopes. Only two HLA-associated viral polymorphisms were common to both genotypes. In the remaining sites with HLA-associated polymorphisms, there was either complete conservation or no significant HLA association with viral polymorphism in the alternative genotype. This study also highlights the diverse mechanisms by which viral evasion of immune responses may be achieved and the role of genotype variation in these processes. Conclusion: There is little overlap in HLA-associated polymorphisms in the nonstructural proteins of HCV for the two genotypes, implying differences in the cellular immune pressures acting on these viruses and different escape profiles. These findings have implications for future therapeutic strategies to combat HCV infection, including vaccine design. (HEPATOLOGY 2009.)

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a genetically diverse RNA virus with six major genotype groups that differ by approximately 30% at the nucleotide (RNA) level.1 Among these, HCV genotypes 1 and 3 are the most prevalent genotypes in Australia and northern Europe. The extensive intergenotype genetic variation is likely to have important implications for the host's cellular immune responses to HCV, which are an important correlate of infection outcome (reviewed by Klenerman and Hill2). These responses are stimulated by the presentation of internally processed viral peptides (epitopes) by human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I molecules to CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Viral polymorphisms within or flanking these epitopes can result in escape from HLA-restricted CTL responses, providing an effective mechanism for the virus to subvert host immune control (reviewed by Bowen and Walker3). We and others4, 5 have shown that viral polymorphisms in the HCV genotype 1 genome are associated with specific HLA class I alleles, indicating adaptation of HCV to HLA-restricted immune pressure.

So far, the majority of studies examining cellular immune responses in individuals infected with HCV have focused on genotype 1 and have used peptide libraries based on a HCV genotype 1 sequence, even when examining individuals infected with genotype 3 (reviewed by Ward et al.6 and Bowen and Walker7). Given the extent of genetic diversity distributed throughout their genomes, it would be anticipated that the repertoire of HLA-restricted viral epitopes could be distinct for the different HCV genotypes. Conversely, areas of the HCV genome that are conserved across genotypes 1 and 3 can provide a basis for cross-genotype HLA-restricted CTL responses, as has recently been demonstrated for an HLA-A1–restricted epitope in the NS3 protein of HCV.8 Furthermore, cellular immune responses are thought to play a role in response to interferon-based therapy, although this remains controversial. Given the higher response rate to interferon-α and ribavirin therapy in genotype 3 compared with genotype 1,9, 10 understanding potential immunological differences will be important. Better understanding of the selection pressures on HCV is also likely to be relevant for new anti-HCV drugs11 and for HCV vaccine design.

We performed HLA typing and HCV sequencing from individuals with chronic HCV infection to compare the viral adaptation profiles between genotypes 1a and 3a.

Abbreviations

CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte, HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; NS, nonstructural; P, position; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Individuals with chronic HCV genotype 1a (n = 187) or 3a (n = 136) infection were recruited from Australia (n = 145), Switzerland (n = 99), and the UK (n = 79). All HCV sequences were obtained from HCV treatment-naïve individuals. Written informed consent was obtained from participants, and local Institutional Review Board approval was obtained by the contributing centers.

DNA and Viral RNA Extraction

DNA was obtained from whole blood using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit following the manufacturer's guidelines. Viral RNA was extracted from plasma samples using either the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN) or the COBAS AMPLICOR HCV Specimen Preparation Kit version 2.0 (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

HLA Genotyping

Sequenced-based four-digit HLA class I typing was performed by direct DNA sequencing methods as described.4

Bulk Viral Sequencing and HCV Genotyping

Initial reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the SuperScript III One-Step RT-PCR System with a Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase PCR kit (Invitrogen) was performed. The first-round product was then used in several nested second-round PCRs containing generic or genotype-specific primer pairs (primer sequences available upon request) together with the Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity Kit (Invitrogen) to cover the area from NS2 to NS5B. Resultant PCR products were bulk (population)-sequenced using the BigDye Terminator version 3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's recommendations, and electropherograms were edited using Assign software (Conexio Genomics). Mixtures were identified where the secondary peak was >20% of the main peak. HCV subtypes were assigned by clinical tests using commercial assays (INNO-LiPA HCV II, Innogenetics Gent) and confirmed by way of phylogenetic analysis (Supporting Fig. 3).

Due to the variability of the HCV genome, some samples failed to produce a PCR product and as a result, some individuals did not contribute sequences for all nonstructural proteins. The number of individuals that contributed sequences was as follows (genotype 1a/genotype 3a): NS2:170/129, NS3:181/136, NS4a:153/90, NS4b:178/108; NS5a:174/122, NS5b: 182/128. For the analysis that adjusted for phylogenetic relatedness and for the assessment of sequence variation between and within genotypes, we only included sequences with >90% coverage for the respective protein (see Statistical Methods). For the NS5b protein, the analysis was restricted to residues 2421-2870, because the number of individuals with sequence coverage for the rest of NS5B was insufficient to perform the statistical analyses. The number of individuals that contributed sequences for the analysis that adjusted for phylogenetic relatedness was as follows (genotype 1a/genotype 3a): NS2: 149/108, NS3: 105/93, NS4a: 148/86, NS4b: 93/64; NS5a: 86/72, NS5b: 85/80.

Statistical Methods

HLA Association with Viral Polymorphism.

Associations between HLA alleles and amino acid distribution at each residue of the HCV proteins were assessed via Fisher's exact tests for classification as consensus versus nonconsensus amino acid using S-Plus 8.0 (Insightful Corporation, Seattle, WA).

Assessment of Phylogenetic Relatedness.

Polymorphisms detected across viral genomes are likely to be the result of natural selection (such as HLA-restricted immune pressure) and neutral evolution. The ability to differentiate between these two evolutionary processes could be compromised in cases where an HLA allele is overrepresented in a subgroup of individuals that have viral sequences sharing a recent common ancestor. In these cases, an association between an HLA allele and viral polymorphism may reflect a founder effect rather than a true site of viral adaptation to immune pressure. Others have previously used phylogenetic methods to adjust for these potential confounding factors.5, 12 In this study, we addressed this issue by identifying clusters of possibly related sequence and assessing the potential impact of such relatedness by performing analyses stratified by clusters. This approach is based on the notion that within relatively homogeneous clusters of possibly related sequences, the distributions of HLA types should be random. Clusters were determined using the robust partitioning around medoids method of Kaufman and Rousseeuw13 based on the binary presence/absence of consensus at each residue. Optimal clustering was determined via the average silhouette width, comparing the within to between cluster dissimilarities. Numbers of clusters were determined through plots of the silhouette values across numbers of clusters, and individuals were assigned to their nearest cluster. Genotype 3 sequences were aligned against genotype 1a sequences to maximize comparability between the genotypes.

Stratified Analysis by Way of Mantel-Haenszel Tests.

Associations between polymorphisms at each amino acid residue and the HLA alleles in the population adjusted for cluster strata were then assessed by Mantel-Haenszel tests. Because this procedure combines the associations between viral polymorphisms and HLA alleles within the clusters of possibly related sequences, the risk of confounding through overrepresentation of HLA alleles in phylogenetically related sequences was minimized. Because this analysis is based on calculating similarities between viral sequences that have sufficient overlap, we only included sequences with >90% coverage for the respective protein (genotype 1a, n = 187; genotype 3a, n = 136). Analyses were performed by protein.

Only associations with P ≤ 0.01 for both the Fisher's exact test and the Mantel-Haenszel method were reported. In addition, because P values associated with relatively small frequencies can be biased and dominated by small numbers of misclassified cases, we restricted our report to associations for which there were at least five nonconsensus amino acids and at least five carriers of the HLA allele.

False Discovery Rates and q Values.

False discovery rates (FDR) and associated q values14, 15 need to take account of both the discreteness of the test statistics and also the strong correlations between tests. We obtained the null distributions by replicating the analysis to create the appropriate tables and marginal frequencies, fixing the margins but imputing random hypergeometric table values subject to these fixed margins. Because of the replication of similar tables with corresponding marginal frequencies within each analysis, 50 imputed random tables for each association were sufficient to provide an accurate estimate of the overall null P value distribution. FDR and q values were then obtained similarly to Storey and Tibshirani.15

Inclusion of All HCV Sequences.

Exclusion of HCV sequences with <90% coverage of a particular protein could potentially bias the dataset toward individuals in whom viral sequencing has been more successful (for example, those with more conserved sequences relative to the primers or higher viral loads). We therefore also performed a subsequent analysis including all available HCV sequences. Because the cluster analysis requires higher sequence coverage, we only report results based on P ≤ 0.01 and a q value cutoff of ≤0.2 for the entire dataset.

Data Deposition

The HCV sequences analyzed in this study have been deposited in GenBank. For a listing of accession numbers, please see Supporting Information in the online version of this article.

Results

Characteristics of Study Population.

This study population is drawn from three cohorts of chronically HCV-infected individuals, comprising predominantly males (73%) who had acquired HCV through injection drug use (65%), with a median age of 46 years (Table 1). There were 130 (40%) individuals coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the study, of whom the majority (91% in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study and 75% in the Australian cohort) had a CD4+ T cell count above 200 cells/μL, which others have shown is generally sufficient to maintain HCV-specific CD8+ T cell activity.16, 17 As shown in Supporting Fig. 1, the HLA class I allele frequency distribution was typical of Caucasian populations and was similar across the study groups. Of the 45 HLA alleles with a frequency of 2% or more, only three alleles differed significantly between the genotypes and four between the cohorts (Supporting Fig. 1). Hence, with only a few exceptions, the frequency of the HLA types of individuals infected with either genotype was similar, providing the basis for comparison of HLA-restricted immune pressure on the two genotypes.

| Australian Cohort(n = 145) | Swiss HIV Cohort Study (n = 99) | Oxford (UK) Cohort (n = 79) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCV genotype 1a, n (%) | 87 (60) | 62 (63) | 38 (48) |

| HCV genotype 3a, n (%) | 58 (40) | 37 (37) | 41 (52) |

| Mode of transmission, n (%)* | |||

| Injection drug use | 35 (49) | 78 (79) | 48 (61) |

| Blood transfusion | 21 (29) | 1 (1) | 8 (10) |

| Other | 16 (22) | 20 (20) | 23 (29) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 28 (20) | 37 (38) | 23 (29) |

| Median age (interquartile range), years | 46 (39–52) | 44 (40–48) | 51 (45–56) |

| HIV-infected (%) | 31 (21) | 99 (100) | 0 (0) |

- * Unknown in 73 subjects from the Australian cohort.

HLA-Associated Viral Polymorphisms Within the Nonstructural Proteins of Genotypes 1a and 3a.

We first examined the viral adaptation pattern across the nonstructural proteins for both genotypes. In this analysis, associations between HCV polymorphism and carriage of specific HLA class I alleles at each residue of the nonstructural HCV proteins were investigated. Significant associations with an odds ratio >1 are consistent with mutational escape from HLA-restricted cellular immune pressure; viral polymorphisms that abrogate HLA-restricted CTL responses are overrepresented in the presence of the restricting HLA allele. Associations with an odds ratio <1 indicate overrepresentation of consensus in individuals that carry the respective HLA allele, indicating sites where the consensus viral sequence appears best adapted to T cell responses acting at these sites across the host population.4, 5, 18, 19 In order to minimize confounding through founder effects,12 the analysis was adjusted for viral phylogenetic relatedness (see Statistical Methods).

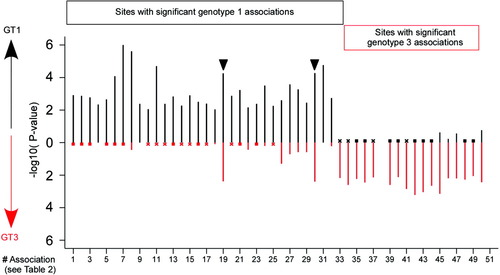

We identified 51 HLA-associated viral polymorphisms in total for both genotypes with P < 0.01 in the unadjusted and phylogeny-adjusted analysis (32 for genotype 1a and 19 for genotype 3a; Table 2A and 2B). Only two HLA-associated viral polymorphisms were common between the genotypes (HLA-A*0101 at NS3-1444 and HLA-B*1501 at NS5B-2467 [boxes in Table 2A and 2B]). For the remaining 47 sites where an HLA-associated viral polymorphism was identified in one HCV genotype, 12 were completely conserved in the alternative genotype, with no evidence for common HLA-restricted polymorphism across genotypes at the remaining sites (Fig. 1). With respect to the different HLA loci, we identified 14, 25, and 12 HLA-associated viral polymorphisms for HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C, respectively. However, in some instances (particularly for HLA-B and HLA-C), we have shown4 that associations at the same site for HLA alleles of different loci can, in part, be explained by the linkage disequilibrium that is observed within the major histocompatiblity complex. Of those associations shown in Table 2A and 2B, three are associated with strongly linked HLA-B and HLA-C alleles within common extended major histocompatiblity complex haplotypes (noted in Table 2A).

| # | Protein | Residue | HLA | Con-sensus | Unadjusted P-value | Phylogeny-adjusted P-value | q-value | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NS2 | 824 | C1502 | V | 0.0012 | 0.0007 | 0.37 | 10.0 |

| 2 | NS2 | 841 | C0401 | W | 0.0014 | 0.0021 | 0.37 | 22.0 |

| 3 | NS2 | 851 | C1502 | T | 0.0016 | 0.0002 | 0.38 | 29.0 |

| 4 | NS2 | 856 | B3503 | Q | 0.0046 | 0.0031 | 0.59 | 23.0 |

| 5∧ | NS2 | 957 | B1302 | R | 0.0022 | 0.0008 | 0.42 | 10.0 |

| 6∧ | NS2 | 957 | C0602 | R | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.04 | 8.8 |

| 7*∧ | NS2 | 958 | B3701 | D | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.00 | 810.0 |

| 8∧ | NS2 | 958 | C0602 | D | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.00 | 38.0 |

| 9 | NS2 | 962 | B3503 | N | 0.0042 | 0.0021 | 0.55 | 19.0 |

| 10 | NS2 | 998 | B1302 | N | 0.0090 | 0.0087 | 0.76 | 6.3 |

| 11∧ | NS2 | 1006 | B3701 | R | 0.0000 | 0.0004 | 0.01 | 44.0 |

| 12∧ | NS2 | 1006 | C0602 | R | 0.0042 | 0.0089 | 0.55 | 6.8 |

| 13 | NS2 | 1017 | B1501 | G | 0.0015 | 0.0098 | 0.37 | 7.3 |

| 14 | NS3 | 1341 | A1101 | A | 0.0054 | 0.0026 | 0.61 | 11.0 |

| 15 | NS3 | 1366 | C1502 | A | 0.0013 | 0.0009 | 0.37 | 36.0 |

| 16 | NS3 | 1368 | B5101 | S | 0.0031 | 0.0002 | 0.51 | 23.0 |

| 17* | NS3 | 1398 | B0801 | K | 0.0041 | 0.0061 | 0.55 | 8.0 |

| 18* | NS3 | 1403 | B0801 | L | 0.0091 | 0.0067 | 0.77 | 12.0 |

| 19* | NS3 | 1444 | A0101 | F | 0.0001 | 0.0005 | 0.04 | 0.1 |

| 20 | NS3 | 1495 | A0101 | K | 0.0013 | 0.0079 | 0.37 | 6.7 |

| 21 | NS3 | 1503 | C1203 | A | 0.0006 | 0.0000 | 0.18 | 31.0 |

| 22 | NS3 | 1635 | A1101 | V | 0.0070 | 0.0083 | 0.67 | 6.5 |

| 23 | NS4A | 1695 | B2705 | I | 0.0041 | 0.0033 | 0.55 | 11.0 |

| 24 | NS4B | 1876 | B4001 | T | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.11 | 23.0 |

| 25 | NS5A | 2000 | C0401 | M | 0.0056 | 0.0025 | 0.61 | 12.0 |

| 26 | NS5A | 2036 | A2402 | T | 0.0026 | 0.0020 | 0.45 | 16.0 |

| 27 | NS5A | 2155 | B3501 | P | 0.0003 | 0.0034 | 0.10 | 38.0 |

| 28 | NS5A | 2227 | B4403 | I | 0.0005 | 0.0001 | 0.18 | 33.0 |

| 29 | NS5A | 2234 | B5101 | R | 0.0035 | 0.0002 | 0.51 | 23.0 |

| 30$ | NS5B | 2467 | B1501 | Q | 0.0001 | 0.0004 | 0.04 | 10.0 |

| 31 | NS5B | 2510 | A3101 | S | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.01 | 63.0 |

| 32 | NS5B | 2796 | C0303 | G | 0.0018 | 0.0014 | 0.39 | 19.0 |

- Adjusted for phylogenetic relatedness using sequences with >90% coverage for the respective protein. HLA associations common to genotypes are boxed.

- ∧ HLA alleles within an extended MHC haplotype.

- * Within known epitopes.

- $ The HLA-B*1501 association at NS5B-2467 falls within a predicted epitope (SYFPEITHI and BIMAS).

| # | Protein | Residue | HLA | Con-sensus | Unadjusted P-value | Phylogeny-adjusted P-value | q-value | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33 | NS2 | 981 | B4403 | I | 0.0066 | 0.0029 | 0.78 | 9.6 |

| 34 | NS3 | 1073 | A2402 | T | 0.0025 | 0.0005 | 0.69 | 16.0 |

| 35 | NS3 | 1133 | A0301 | V | 0.0058 | 0.0029 | 0.78 | 12.0 |

| 36 | NS3 | 1383 | B5101 | A | 0.0035 | 0.0085 | 0.74 | 13.0 |

| 37 | NS3 | 1416 | B0702 | A | 0.0073 | 0.0057 | 0.78 | 7.7 |

| 38* | NS3 | 1444 | A0101 | F | 0.0041 | 0.0070 | 0.74 | 0.2 |

| 39 | NS3 | 1560 | A2402 | S | 0.0025 | 0.0097 | 0.69 | 16.0 |

| 40* | NS3 | 1637 | A1101 | L | 0.0075 | 0.0074 | 0.78 | 5.9 |

| 41 | NS3 | 1646 | A0101 | M | 0.0014 | 0.0050 | 0.63 | 13.0 |

| 42 | NS4B | 1759 | B5701 | A | 0.0006 | 0.0066 | 0.63 | 17.0 |

| 43 | NS5A | 1982 | B5701 | D | 0.0009 | 0.0001 | 0.63 | 17.0 |

| 44 | NS5A | 2248 | B3501 | T | 0.0022 | 0.0065 | 0.69 | 18.0 |

| 45 | NS5A | 2320 | A0201 | G | 0.0007 | 0.0023 | 0.63 | 0.1 |

| 46 | NS5A | 2320 | C1502 | G | 0.0062 | 0.0068 | 0.78 | 12.0 |

| 47 | NS5A | 2321 | C0602 | A | 0.0061 | 0.0063 | 0.78 | 14.0 |

| 48 | NS5A | 2354 | B3501 | S | 0.0053 | 0.0081 | 0.78 | 9.0 |

| 49 | NS5A | 2367 | B5101 | S | 0.0087 | 0.0085 | 0.83 | 16.0 |

| 50 | NS5A | 2372 | A1101 | V | 0.0036 | 0.0054 | 0.74 | 8.6 |

| 51$ | NS5B | 2467 | B1501 | Q | 0.0039 | 0.0012 | 0.74 | 22.0 |

- Adjusted for phylogenetic relatedness using sequences with >90% coverage for the respective protein. HLA associations common to genotypes are boxed. Genotype 3a HLA-associated viral polymorphisms at position NS5A-2367 and NS5A-2372 correspond to positions 400 and 405 in the NS5A protein, respectively.

- * Within known epitopes.

- $ The HLA-B*1501 association at NS5B-2467 falls within a predicted epitope (SYFPEITHI and BIMAS).

Comparison of P values between genotypes at HLA-associated viral polymorphism sites reveals limited overlap. The P values (listed in Table 2) that define the significance of the HLA-associated polymorphism is shown as a black bar for genotype 1a and as a red bar for genotype 3a (−log10 scale). The P value for the alternative genotype at the same site and for the same HLA type is indicated. A cross indicates where the sequences for the alternative genotype at the selected site are completely conserved. A square indicates where the alternative genotype at the selected site has a P value >0.9. In three sites (#4, #9, #31) there were fewer than three individuals carrying the respective HLA allele and the comparison was therefore not performed. The two sites with significant associations for the same HLA type and genotype are indicated by an arrowhead; the P values of the corresponding genotype 3 associations (sites #38 and #51) are shown at the genotype 1 sites.

Four HLA-associated polymorphisms for genotype 1a were within previously published epitopes (marked with an asterisk in Table 2A). Furthermore, when we expanded the dataset to include all available HCV sequences (including sequences with <90% sequence coverage), HLA-B*2705-associated viral polymorphisms at positions NS5B-2841 and 2846 were detected for genotype 1a, which fall within a described epitope20 (Table 3). Two HLA-associated viral polymorphisms for genotype 3a fall within previously described epitopes, including the overlapping site at NS3-1444, which falls within the NS3-1436 epitope restricted by HLA-A*0101, where the consensus sequence is identical to that in genotype 1a (Fig. 2). Not surprisingly, the site NS3-1444 is also a highly polymorphic residue for both genotypes (Fig. 3). This epitope has been the focus of previous attention in that the escape mutation has come to dominate population sequences and emerge as consensus (negatope), consistent with the fact that HLA-A*0101 is a relatively high-frequency HLA allele, present in ≈15% of the study population and suggestive of similar or improved replicative capacity of the adapted variant.8 The HLA-B*1501 association at NS5B-2467 falls within an epitope that has been predicted using Web-based epitope prediction programs (SYFPEITHI and BIMAS21, 22).

| # | Protein | Residue | HLA | Consensus | Unadjusted P-value | q-value | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* | NS2 | 958 | B3701 | D | 0.0000 | 0.00 | 880.0 |

| 2 | NS2 | 958 | C0602 | D | 0.0000 | 0.00 | 33.0 |

| 3 | NS2 | 1006 | B3701 | R | 0.0000 | 0.00 | 46.0 |

| 4 | NS3 | 1272 | A3201 | H | 0.0005 | 0.19 | 25.0 |

| 5* | NS3 | 1397 | B0801 | K | 0.0002 | 0.14 | 11.0 |

| 6* | NS3 | 1444 | A0101 | F | 0.0000 | 0.00 | 0.1 |

| 7 | NS3 | 1495 | A0101 | K | 0.0004 | 0.18 | 6.0 |

| 8 | NS3 | 1637 | B4403 | L | 0.0000 | 0.00 | 22.0 |

| 9 | NS4B | 1723 | B3701 | M | 0.0002 | 0.13 | 38.0 |

| 10 | NS5A | 2155 | B3501 | P | 0.0002 | 0.10 | 34.0 |

| 11 | NS5B | 2467 | B1501 | Q | 0.0000 | 0.00 | 9.5 |

| 12 | NS5B | 2510 | A3101 | S | 0.0000 | 0.00 | 94.0 |

| 13* | NS5B | 2841 | B2705 | A | 0.0004 | 0.18 | 12.0 |

| 14* | NS5B | 2846 | B2705 | M | 0.0005 | 0.19 | 12.0 |

- Phylogenetic adjustments were not performed, because some sequences in the unrestricted dataset contained small fragments. Only associations with q < 0.2 are shown.

- $ Association #8 is for HCV genotype 3a; the remaining associations are for HCV genotype 1a.

- * Within known epitopes.

Different variation patterns between genotypes within published epitopes containing HLA-associated viral polymorphism sites reflect divergent cellular immune pressures acting on the virus. The proportion of nonconsensus residues within and flanking published epitopes is indicated for individuals carrying the respective HLA allele (black bars) and for those not carrying the HLA allele (white bars). Arrowheads indicate significant associations (P < 0.01 in unadjusted and phylogeny-adjusted analysis). *P < 0.01 in unadjusted analysis only. The published epitope is shown above each graph for genotype 1 and 3 although they have only been confirmed for genotype 1 (with the exception of the NS3-A*0101 epitope). The NS5B-B*1501 epitope has been predicted using Web-based epitope prediction programs (SYFPEITHI and BIMAS). The association within the NS5B-B*2705 epitope could only be assessed in the unrestricted dataset as only four HLA-B*2705–positive individuals had >90% sequence coverage for NS5B (see Subjects and Methods). Note minor variation from data presented in Gaudieri et al.11 due to inclusion of HCV genotype 1B sequences and selection based on two-digit HLA typing in Gaudieri et al. SYFPEITHI scores for consensus amino acids are indicated in brackets above the epitopes. $SYFPEITHI does not predict the published octamer epitope but a nonamer epitope at position 1635-1643 (scores 27 and 17 for genotypes 1 and 3, respectively).

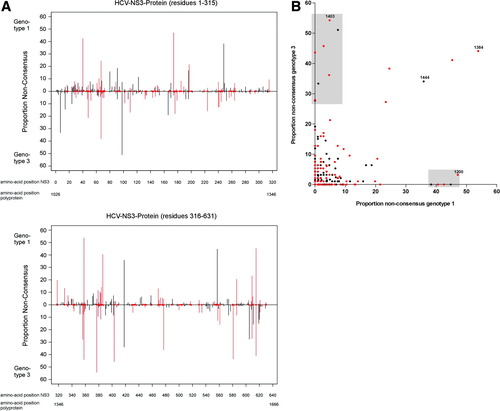

(A) Polymorphism profile of the HCV NS3 protein for genotypes 1a and 3a shows differences in consensus amino acids and sites of polymorphism. Vertical bars indicate the proportion of sequences with nonconsensus residues for genotype 1a above the line and genotype 3a below the line. A red circle along the x-axis and red bars indicate residues with a different consensus amino acid for the genotypes. Similar plots for NS2, NS4, NS5A, and NS5B are provided in Supporting Fig. 2. (B) Correlation of polymorphism rates between genotypes for the HCV NS3 protein. Black dots indicate residues with identical consensus amino acids for both genotypes; red dots indicate residues where the consensus amino acid differs between genotypes. Some residues are conserved for one genotype but display a high polymorphism rate for the alternative genotype (indicated by the shaded areas). The two residues 1200 and 1403 indicate examples of residues with different consensus and with highly different polymorphism rates between the genotypes. Residue 1384 is highly polymorphic for both genotypes and has a different consensus. Residue 1444, which represents an escape site for an NS3-A*0101 epitope (Fig. 2) is polymorphic for both genotypes and shares the identical consensus amino acid. Similar plots for NS2, NS4, NS5a, and NS5b are provided in Supporting Fig. 2.

Amino Acid Variation Within Published and Predicted Viral Epitopes that Contain a Viral Adaptation Site Show Different Patterns of Viral Adaptation for Genotype 1a and 3a.

The proportion of nonconsensus residues within and flanking published epitopes is indicated in Fig. 2 for individuals carrying the respective HLA allele and for those not carrying the HLA allele. Carriage of the restricting HLA allele was associated with viral polymorphisms at several sites within immunogenic epitopes, consistent with viral escape from HLA-restricted immune pressure. At multiple sites, including experimentally established viral escape sites (for example, NS3-1397-1398 for HLA-B*0801 and NS5B-2841 and 2846 for HLA-B*270520, 23-25), there was nearly complete conservation in the alternative genotype, even in individuals carrying the relevant HLA alleles (Fig. 2). Although in most epitopes only one site reached statistical significance, the polymorphism rate in those individuals expressing the relevant HLA type was clearly higher at additional sites within the epitope (for example, position [P]1 and P2 for the NS2-957 HLA-B*3701; P2 and P3 for the NS3-1395 HLA-B*0801 epitope; P1-P7 for the NS5B-2841 HLA-B*2705-epitope) (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the HLA-A*1101–associated viral polymorphism at NS3-1637 for genotype 3a falls within the described NS3-1636 HLA-A*1101 epitope, but the HLA-A*1101-associated viral polymorphism for genotype 1a flanks this epitope at 1635 (Fig. 2). Of note, the epitope prediction program SYFPEITHI21 predicts a nonamer epitope at positions 1635-1643 for both genotypes, but not the published octamer epitope.

For the NS3-B*0801 and the NS5B-B*2705 epitopes, the Web-based epitope prediction program SYFPEITHI21 predicted good epitope binding for both genotypes, mainly based on similar anchor residues. Nevertheless, genotype 3 sequences were completely conserved at sites with HLA-associated polymorphisms in genotype 1 sequences. This may be due to poor immunogenicity of the genotype 3 sequences despite good predicted binding, divergent epitope processing pathways, or higher fitness costs of potential escape mutations in genotype 3 sequences. Furthermore, at least one substitution was present in every genotype 1–infected individual carrying HLA-B*2705. Of the HLA-B*2705–positive individuals infected with genotype 1, 60% carried more than one substitution in the HLA-B*2705 epitope, whereas there was almost complete conservation in genotype 3–infected individuals.

From the seven putative viral adaptation sites identified in our previous study within NS3,4 four sites (NS3-1397,1403,1444,1635) are replicated and associated with the identical HLA allele using the more conservative cutoff in this study. Furthermore, in our recent study exploring the potential overlap between HLA-restricted immune pressure and anti-HCV drug resistance mutations,11 we tested for HLA associations at various drug-resistance sites. The HLA associations observed in that study are reproduced in the analysis performed here (using the Fisher's exact test for the entire dataset) but are not included as they fall above the stringent cutoff set in this study. Three sites shown in Tables 2 and 3 overlapped with HLA-associated viral polymorphisms identified by Timm et al.5 (NS3-1398, NS3-1444, NS5B-2841). In addition, three sites identified in the report by Timm et al. were of borderline significance in our study (NS2-881, P = 0.04; NS3-1019, P = 0.07; NS5A-2153, P = 0.02). However, this comparison was hampered by the different HLA typing resolution used.

Different Polymorphism Profiles for HCV Genotypes 1a and 3a Likely to Impact on Viral Presentation to the Host's Immune Response.

In order to better understand the limited overlap in the HLA-restricted immune pressure across the nonstructural proteins of genotypes 1 and 3, we investigated the genetic characteristics of the two genotypes that could result in differences in the viral adaptation profiles observed in our analysis. We initially examined the sequence variation between the genotypes, because this will have a significant effect on the repertoire of T cell epitopes that are presented by the host HLA alleles. Viral polymorphism profiles for each of the nonstructural proteins were compared for the two HCV genotypes, as shown in Fig. 3 and Supporting Fig. 2. In this analysis, we considered the rates of amino acid polymorphism defined as the overall percentage of nonconsensus amino acids at a particular site. This analysis revealed substantial differences in the polymorphism rates between the genotypes in that many polymorphic sites in genotype 1 sequences were conserved in genotype 3 and vice versa (Fig. 3A,B).

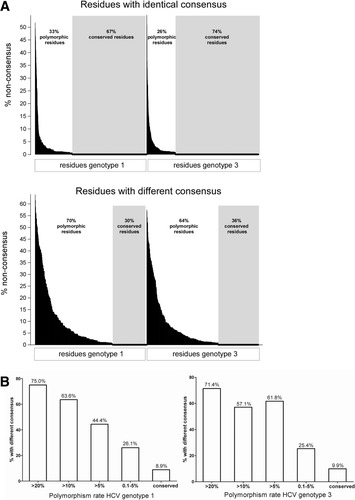

We also noted that sites where the two HCV genotypes shared a common consensus amino acid were more than twice as likely to be conserved at the population level (67% in genotype 1a; 74% in genotype 3a) compared with sites where the genotype consensus amino acids differed (genotype 1a, 30%; genotype 3a, 36%) as shown in Fig. 4A. Similarly, the majority of residues with high polymorphism rates displayed different consensus amino acids between the genotypes (Fig. 4B). Hence, the bulk of intragenotype variation occurs at sites where the consensus sequence varies between the genotypes. These genotype differences are likely to result in substantial variation in the escape potential of sites across the viral genome to HLA-restricted immune pressure.

Residues with different consensus amino acids between genotypes are more polymorphic than residues with identical consensus. (A) The polymorphism rates of all residues from HCV-NS2 to HCV-NS5B are shown for residues where the consensus is identical and for residues where the consensus differs between the genotypes. The residues are sorted by polymorphism rate, conserved residues are completely conserved in all individuals. (B) The proportion of residues with different consensus between the genotypes is indicated on the y-axis for different polymorphism rates within a genotype on the x-axis. The majority of highly polymorphic residues display different consensus amino acids between the genotypes.

Divergent Consensus Sequences, Proteasomal Cleavage Sites, and Selective Pressures Between Genotypes 1a and 3a.

Overall, the consensus amino acid sequence differed between HCV genotypes 1a and 3a at 515 of 2,147 residues examined (24%; Supporting Table 1). For a proportion of these sites (32%), the variant amino acid for one genotype was the consensus for the other. However, for many sites the mutational pathway for the genotypes was distinct. We also identified a large number of sites where different consensus sequence variation was predicted to abrogate proteasomal cleavage (55 for genotype 1a, 47 for genotype 3a; Supporting Table 1). Furthermore, when we tested for evidence of positive selection (using the Single-Likelihood Ancestor Counting algorithm implemented in the program HyPhy26) acting at sites across the nonstructural proteins, only five out of 34 sites were common to both genotypes. Overall, the large number of different consensus amino acids and predicted processing sites and the divergent selective pressures between the genotypes are likely to result in differences in the repertoire of HLA-restricted viral epitopes across the genomes (see Supporting Material for a more detailed analysis).

Discussion

In this study, we have shown substantial differences in the patterns of viral adaptation to HLA-restricted immune pressure between HCV genotypes 1 and 3. From the 51 sites with HLA-associated viral polymorphisms, there were only two sites with the identical viral polymorphism and HLA type between HCV genotypes 1a and 3a. In a large majority of sites with significant HLA associations, the alternative genotype was either entirely conserved or there were no polymorphisms in individuals carrying the relevant HLA allele (Fig. 1). More direct comparisons of HCV amino acid variation within published epitopes (Fig. 2) identified similarly distinct polymorphism profiles between HCV genotypes. Together, these findings suggested that the patterns of viral adaptation to the host's immune pressure vary considerably between the genotypes. This supported the hypothesis that viral escape is driven by the host's immune pressure and restricted by viral (genotype) characteristics.

This study also served to highlight the diverse mechanisms by which viral evasion of CTL responses may be effectively achieved, and the potential role of genotype sequence variation in these processes. First, the substantial differences in the consensus sequences for HCV genotypes 1a and 3a can abrogate HLA binding to critical anchor residues within viral epitopes, as suggested by the complete abrogation of predicted HLA-B*3701 binding to the NS2 957-964 epitope in genotype 3a shown in Fig. 2. Second, genetic distance and physicochemical properties may have an important influence on genotype-specific mutational pathways resulting in differences in the escape potential of sites across the genome between the genotypes (Supporting Table 1). This is also highlighted in Fig. 4, which shows that at sites of high intragenotype variation the consensus amino acid of the two genotypes tend to differ, implying divergent mutational potential between the genotypes. Third, the divergent sequence context flanking immunogenic epitopes may have a substantial impact on epitope processing, in keeping with the finding that ≈20% of genotype-associated amino acid variants are predicted to influence proteasomal cleavage of target peptides. Fourth, genotype-specific polymorphisms outside the anchor positions may impair the recognition of the HLA-epitope complex by CD8+ T cells.

Dazert and colleagues25 have recently demonstrated that CTL escape mutations within the HLA-B27 NS5B-2841 epitope occur in the majority of individuals carrying HLA-B*2705, but spare the binding anchors at positions 2 and 9. The nearly complete conservation of the anchor positions (P9 more so than P2) irrespective of carriage of the restricting allele for both genotypes (Fig. 2) reflects the substantial fitness cost of polymorphisms at these sites.25 However, more than one polymorphism was present in most HLA-B*2705–positive genotype 1–infected individuals, in line with the previous observation that clustered mutations outside the anchor position are required for efficient escape.25 In contrast, a single mutation at position 9 appears sufficient to abrogate T cell responses in the A*0101–restricted NS3-1436 epitope8 (Fig. 2).

These analyses also indicated that the evolution of adaptive HCV variants within the nonstructural proteins was set against a background of overall negative selection, in keeping with the wide array of functional roles that these compact and tightly integrated proteins serve (Supporting Material).27 The fact that viral adaptation is highly constrained may help to explain why persistent infection is not always established following HCV infection, and also suggests that viral adaptation to HLA-restricted CTL could frequently incur costs to viral replicative capacity.

Given the similar function and structure of nonstructural HCV proteins in genotypes 1 and 3, the large number of amino acid differences in the genotype consensus sequences might be surprising. However, we found that in a large proportion of these sites (32%) an intragenotype amino acid polymorphism for one genotype was the consensus for the alternative genotype. This suggested that functional constraints within the tightly integrated HCV protein structure are likely to limit the possible alternative amino acids that are compatible with the function of the protein, and that mutational pathways would result in an accumulation of alternative amino acids that were closest to the consensus sequence. In this respect, at some sites the consensus of one genotype might represent the escape variant of the alternative genotype.

This study has some limitations. First, it is likely that our analysis did not detect relevant HLA-associated viral polymorphisms for rare HLA alleles due to low numbers of individuals carrying the respective allele. Second, the inclusion of a substantial proportion (40%) of individuals coinfected with HIV might influence the degree of HLA-associated viral polymorphisms as severe HIV-induced immunosuppression is associated with lower HCV-specific T cell responses.16, 17 However, the large majority (90%) of the coinfected individuals in this study had a CD4+ T cell count above 200 cells/μL. We would therefore expect that the HLA-restricted immune pressure in the coinfected individuals would be similar to that for monoinfected individuals. In addition, HCV infection precedes HIV infection in the large majority of cases.28 Therefore, escape mutations that are established during acute infection are likely to be under similar immune pressure in HCV-monoinfected and HIV/HCV-coinfected individuals. Third, although we checked for phylogenetic relatedness, such adjustments are always estimations, and one cannot exclude the possibility that in some instances an association between an HLA allele and viral polymorphism may still retain an element of founder effect confounding. Fourth, in many instances the HLA-restricted polymorphisms represent putative escape mutations within potential epitopes that have not been experimentally confirmed. However, all these limitations would affect both genotypes equally so the important conclusion that the selection pressures differ markedly between genotypes should not be substantially affected.

In summary, we have identified major differences between HCV genotypes 1a and 3a in the patterns of HLA-associated viral polymorphisms across the nonstructural proteins indicating largely independent, nonoverlapping T cell responses. Differences in the polymorphism profiles and consensus amino acids between the genotypes correlated with the lack of overlap in viral adaptation sites. Accordingly, sequence content is highly relevant in determining HLA-restricted immune pressure within the genotypes, and the epitope repertoire generated for the two genotypes in the same HLA population would likely have limited overlap. The two adaptation sites that overlap between the genotypes were found in areas of conservation, and one falls within an HLA-A1–restricted epitope that has recently been shown to induce CTL responses in individuals infected with genotypes 1 and 3.8 Cross-genotype epitopes are likely to occur in predominantly conserved areas with similar consensus sequence. These results may provide some explanation as to the relative lack of cross-protection between genotypes in HCV-infected individuals29, 30 and may be relevant to the difference in the response rates to immunomodulatory-based therapy with interferon-α and ribavirin.9, 10, 31

The different patterns of in vivo immune pressure on HCV as reflected by the limited overlap in viral adaptation between the genotypes also have implications for HCV vaccine design. T cell vaccine immunogens that contain escaped amino acids may be poorly immunogenic in some HLA contexts within a host population. In this respect, knowledge of viral escape patterns is important for generating immunogenic T cell vaccines. The limited overlap in putative escape patterns between genotypes observed in this study suggests that this information has to be generated for the genotypes separately.

Acknowledgements

We thank the individuals and clinical staff at the different sites that have contributed to this study and the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. We also thank Dr. Larry Park and Kiloshni Naidoo for their contribution. The members of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study are M. Battegay, E. Bernasconi, J. Böni, HC Bucher, P. Bürgisser, A. Calmy, S. Cattacin, M. Cavassini, R. Dubs, M. Egger, L. Elzi, P. Erb, M. Fischer, M. Flepp, A. Fontana, P. Francioli (President of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, CH-1011 Lausanne), H. Furrer (Chairman of the Clinical and Laboratory Committee), C. Fux, M. Gorgievski, H. Günthard (Chairman of the Scientific Board), H. Hirsch, B. Hirschel, I. Hösli, C. Kahlert, L. Kaiser, U. Karrer, C. Kind, T. Klimkait, B. Ledergerber, G. Martinetti, B. Martinez, N. Müller, D. Nadal, M. Opravil, F. Paccaud, G. Pantaleo, A. Rauch, S. Regenass, M. Rickenbach (Head of Data Center), C. Rudin (Chairman of the Mother & Child Substudy), P. Schmid, D. Schultze, J. Schüpbach, R. Speck, P. Taffé, P. Tarr, A. Telenti, A. Trkola, P. Vernazza, R. Weber, and S. Yerly.