The African Medicines Agency and Medicines Regulation: Progress, challenges, and recommendations

Abstract

In response to the situation of the African healthcare system, the African Medicines Agency (AMA) was established by the African Union (AU) to regulate access to medicines and support the local manufacture of medications. This study aimed to describe the factors that enabled the establishment of the African Medicines Agency and its successes, challenges, and perceived benefits. We reviewed data sources that explored the progress and challenges of the African Medicines Agency and Medicines Regulation in Africa. The SPIDER framework was used to organise the research focus and to extract the keywords for the literature search. The study data were obtained from PubMed Central, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar. Out of 249 studies screened, 19 were selected for this narrative review. Critical successes observed in the agency's establishment include the appointment of a Special Envoy, the selection of its headquarters, and the signing of its treaty by 37 member states. However, it is hindered by poor political commitment, differences in risk-benefits interpretation and organizational structure, weak legal and regulatory frameworks, inadequate financial mechanisms, and inadequate political and policy leadership in some member states. The value of AMA in achieving optimal health outcomes and its other benefits must be considered despite the challenges being encountered. Therefore, all member states should adopt the best procedures in signing and ratifying the treaty and implementing associated commitments to improve efficiency and accountability in African medicine regulation.

Abbreviations

-

- Africa CDC

-

- Africa Centres for Disease Control

-

- AMA

-

- African Medicines Agency

-

- AMRH

-

- African Medicines Regulatory Harmonization

-

- AU

-

- African Union

-

- EAC-MRH

-

- East African Community Medicines Regulatory Harmonisation

-

- GBT

-

- Global Benchmarking Tool

-

- ML

-

- Maturity Levels

-

- NMRAs

-

- National Medicines Regulatory Agencies

-

- NRAs

-

- National Regulatory Authorities

-

- PMPA

-

- Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Plan

-

- UNECA

-

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa

-

- WHO

-

- World Health Organization

1 INTRODUCTION

Africa is the second most populated continent, with 1.5 billion people, accounting for 17.89% of the global population [1]. The continent's population increases by 2.4% per year and has been projected to reach 2.5 billion by 2050 [1]. However, Africa struggles to meet the health needs of its growing population and remains the only global region with the highest rates of mortality and the shortest average lifespan [2]. This situation is further worsened by the threefold challenge of nutritional disorders, communicable diseases, and noncommunicable diseases [2, 3]. The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa reported that Africa imports ~94% of its medicinal and pharmaceutical products, which is exceedingly lower than the standard of expected local manufacture-to-import ratio [4-6]. Furthermore, potential local manufacturers face a range of threats from a lack of adequate infrastructure and government support to political challenges that constrain the local industry and a lack of public trust [7]. This implies that some patients have no access to locally made drugs and may not be able to afford imported ones, some of which are either fake, substandard, or counterfeits [4, 5, 8]. According to a 2018 systematic review, 18.7% of substandard and falsified medicines were found in the African market, the highest percentage globally [9]. These vulnerabilities are, to a great extent, facilitated by poor local pharmaceutical manufacturing and inefficiencies of the National Medicines Regulatory Agencies (NMRAs) [4, 5, 8-10].

All countries in Africa have NMRA or an administrative unit that conducts some or all expected NMRA functions, except for the Sahrawi Republic. Out of this, only about 7% have developed a moderate capacity to carry out their regulatory functions, and over 90% have minimal to no capacity [10]. The NMRAs also have variable functionalities, and they are at different growth, expertise, and maturity levels (ML). They have different autonomy, organizational structures, and scope of activities, including assessment and registration of food and/or drug products, licensing manufacturers and distributors, imports and exports regulation, and regulation of drug promotion and advertisement [10]. The World Health Organization incorporated the “maturity level” concept in their Global Benchmarking Tool to objectively evaluate regulatory systems on a scale of 1 (existence of some elements of the regulatory system) to 4 (operating at an advanced level of performance and continuous improvement) [11, 12]. Out of the 54 African countries, only five including Tanzania, Ghana, Egypt, Nigeria, and South Africa, currently operate at ML3 with their respective scope of products while the remaining countries operate at lower maturity levels [13].

To combat the numerous challenges confronting the NMRAs, the African Medicines Regulatory Harmonization (AMRH) initiative was launched in 2009 as part of the African Union (AU) Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Plan. The major objective of the AMRH initiative was to address the continent's fragmented, ineffective, and poor regulatory systems through collaboration among member states to ensure faster approval and timely access to essential medical products, among others [10, 14]. The AMRH initiative was also a foundation for establishing the African Medicines Agency (AMA) by the AU member states. The AMA represents the regulatory body of the AU, which covers medicine and medicine-related policy formulation and implementation. This agency is intended to ensure the ethical operations of pharmaceutical industries and the drug supply chain activities in general [15]. It also seeks to provide expertise in countries without regulatory competence, strengthen governance in the conduct of pharmacovigilance, provide oversight of clinical trials, promote pharmaceutical manufacturing, and improve efficiency and transparency [16].

The Treaty for the establishment of AMA was formally adopted in 2019. The AU required a minimum of 15 member states to ratify the AMA Treaty before it could be implemented. By contributing to the continental socioeconomic development agenda, AMA is expected to be a key driver in removing technical trade barriers among the regional countries [14, 17-19]. This study describes the factors that enabled the establishment of the AMA, as well as the successes, challenges, and perceived benefits of its establishment.

2 METHODS

2.1 Search strategy

This study was conducted as a narrative review of data sources. It explored the factors that enabled the establishment of the AMA, and the successes, challenges, and benefits of Medicines Regulation in Africa. We used the SPIDER framework to organize the research focus and to extract the keywords for the literature search. This is recommended as an appropriate choice for nonclinical research, which employs qualitative and mixed studies [20]. A breakdown of the applied framework is given below:

Sample—AU member states

Phenomenon of Interest—AMA treaty and medicines regulation

Design—Reports, commentaries, reviews, qualitative studies, quantitative studies, mixed studies

Evaluation—Successes, challenges, perceived benefits, progress

Research type—Mixed method.

2.2 Keywords and databases

The keywords used in the literature search were derived from the SPIDER framework, as illustrated above. The keywords are highlighted as AU member states, African Medicines Agency treaty, challenges, benefits, and progress. To make a search string, the synonyms of these keywords were included as search terms, and these terms were joined with boolean operators, representing conjunctions used in designing search strings to widen or narrow literature searches. Hence, the search string was made by conjoining the search terms with the “AND” boolean operator. outlined as “African Union member states OR AU member states OR AU states” AND “African Medicines Agency treaty OR AMA treaty” AND “challenges OR problems OR drawbacks” AND “Benefits OR rewards OR advantages” AND “progress OR way forward OR reports.” A comprehensive search was then carried out on PubMed, PubMed Central, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar as the selected databases. Additional searches were conducted for gray literature and government reports.

To further ensure the absence of bias during selection, groups of rules that must be fulfilled to include studies in the review were determined. These rules are given as inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.3 Inclusion criteria

-

Studies that highlighted the successes, challenges, progress, and/or recommendations for the African Medicines Agency and Medicine Regulation in Africa and other similar continental initiatives.

-

Articles published in peer-reviewed journals.

-

Articles published on authentic websites such as the World Health Organization, United Nations, African Development Bank, Africa Union, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and New Partnership for African Development.

-

Literature published in English.

-

Articles published between 2010 and 2024.

-

Supporting information and data from commentaries and other reports.

2.4 Exclusion criteria

-

Unavailable full texts.

-

Articles with low relevance to the review topic.

-

Scanty reports.

The collected articles were managed using Mendeley Reference Manager after a prior review of the title and abstract. The retrieved data were discussed narratively to explore the aim of the study.

3 RESULTS

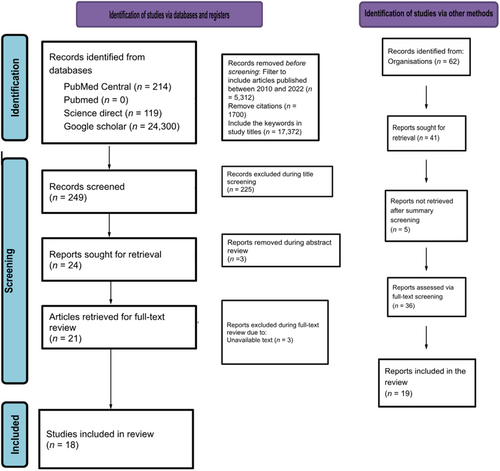

The search yielded zero results in PubMed, 214 in PubMed Central, 119 in ScienceDirect, and 24,300 in Google Scholar. The publication year filter was added, eliminating 40 articles from PubMed Central, 72 from ScienceDirect, and 5200 from Google Scholar. 1700 citations were further removed from Google Scholar, and the search was further narrowed by searching for “African Medicines Agency,” “Medicines,” “Regulatory,” and “Regulation” in the study titles. The total number of studies that underwent title screening was 249. The screening of titles led to the removal of 225 studies, after which three studies were removed during abstract review. This led to a retrieval of 21 articles for the review. Out of this number, four texts were removed during the full-text screening. Thus, 17 studies were used in this review. In addition, we also included two gray literature published by the WHO and the AU, making a total of 19 publications. A chart illustrating this process is given in Figure 1.

Eight of the studies delved into the current scope of medicine regulation in African countries, successes in the AMA's establishment, and how the AMA will benefit the healthcare system [17, 21-26]. Eleven of the studies focused on the global benchmarking standards for national regulatory agencies, current maturity levels for African regulatory agencies, and their respective functions [11-13, 27-34]. Inadequate access to quality and affordable medicines in African countries as well as inadequate local research and the AMA's role in addressing them were highlighted by three of the studies [29, 35, 36]. Two works of literature highlighted the economic commitment needed for the AMA's establishment and its perceived economic benefits [26, 28]. Similarly, the legal requirements and structure, challenges to its establishment, and lessons from previous harmonization initiatives were discussed in 13 studies [10, 22, 24, 26, 27, 30, 36-41]. A study discussed the use of global health diplomacy in AMA's establishment [42].

3.1 Current status of establishment of the AMA, progress and notable milestones

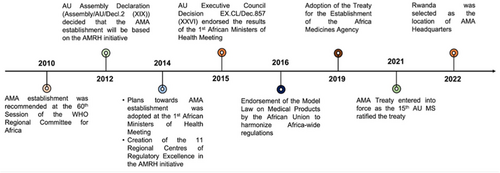

Figure 2 shows the milestones of the AMA establishment [14, 18, 19, 27, 38].

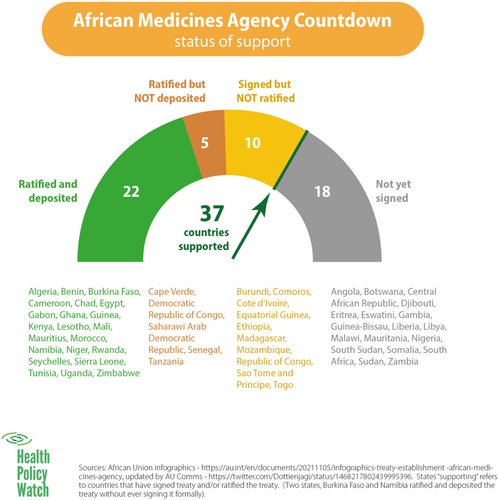

The member states began signing the treaty on June 12, 2019, with Rwanda taking the lead and being the first to sign the treaty [14]. On October 5, 2021, Cameroon became the 15th country to deposit its ratification instrument. Consequently, the AMA Treaty came into force on November 1, 2021 [19]. As of October 2023, 37 of the 55 member states had signed the treaty (Figure 3).

The treaty has recorded remarkable successes due to a combination of efforts, which include the appointment of a Special Envoy to advocate for the treaty among member states, the drive to fulfill the Partnerships for African Vaccine Manufacturing, the accomplishments of other specialized health organizations of the AU, the Africa Centres for Disease Control (Africa CDC), AMRH, AVREF, and mutual working relationship between some NMRAs and relevant stakeholders—government officials, Ministry of Health, security agencies amongst others [30].

The AMA has also tackled the regulation of traditional medicines. Although African countries such as Cameroon, Ethiopia, Ghana, Uganda, and Zimbabwe have adopted WHO recommendations on Traditional Medicines, postmarketing surveillance and follow-up investigations of these medicines' efficacy and safety are poor or nonexistent [37]. Additionally, regulatory policies for these medicines amongst NMRAs in Africa are not harmonized, and this presents a major concern due to Africans' continued dependence on traditional medicines. All these challenges are effectively addressed by incorporating traditional medicines into AMA's scope [32, 38].

Another notable deliverable of the AMA is its ability to merge presently fragmented national pharmaceutical markets on a continental level. It is expected to have a value of over $40 billion by 2030s, owing to Africa's status as the second most populous continent [1, 31, 32]. This consolidated status will improve Africa's statusin collaboration with health agencies, including the WHO [14].

3.2 Medicines regulatory systems and maturity levels in Africa

Table 1 shows the National Regulatory Authorities (NRAs) in African countries operating at Maturity Level 3 as of June 2024. Of the 55 African countries, only six have NRAs with good maturity levels. These NRAs are classified as having ML3; defined as having a stable, well-functioning, and integrated regulatory system [39].

| No. | Country | Regulatory authority | Maturity level | Scope of product | Year announced |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Egypt | Egyptian Drug Authority (EDA) | ML3 | Vaccines (producing) | 2022 |

| 2 | Ghana | Food and Drugs Authority | ML3 | Medicines Vaccines (nonproducing) |

2020 |

| 3 | Nigeria | National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) | ML3 | Medicines Vaccines (nonproducing) |

2022 |

| 4 | South Africa | South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) | ML3 | Vaccines (producing) | 2022 |

| 5 | Tanzania | Tanzania Medicines and Medical Devices Authority (TMDA) | ML3 | Medicines Vaccines (nonproducing) |

2018 |

| 6 | Zimbabwe | Medicines Control Authority of Zimbabwe (MCAZ) | ML3 | Medicines Vaccines (nonproducing) |

2024 |

- Abbreviation: NRAs, National Regulatory Authorities.

3.3 Challenges facing the AMA

Some countries are yet to sign or ratify the treaty due to peculiar challenges, including poor political commitment, corruption, language barriers, clashes, misconceptions, differences in risk-benefits interpretation and organizational structure amongst the countries, weak legal and regulatory frameworks, inadequate financial mechanisms, and inadequate political and policy leadership [14, 35].

Among countries that have signed the treaty, implementing the provisions has been hampered by the lack of human, financial, and material resources [32, 33]. It is estimated that US$100 million will be needed to fund AMA for its first 5 years of operation [14].

4 DISCUSSION

An essential component of any health system is an effective regulatory framework that plays a key role in assuring medical products' quality, safety, and efficacy [34]. This review describes the factors that enabled the establishment of the AMA and its successes, challenges, and perceived benefits. The establishment of the AMA represents a significant milestone in improving healthcare regulation and access across the African continent. Since Rwanda's initial signing of the treaty on June 12, 2019, the progress has been noteworthy, culminating in the treaty coming into force on November 1, 2021, after Cameroon deposited its ratification instrument as the 15th country on October 5, 2021. By October 2023, 37 out of 55 member states had signed the treaty, showcasing widespread support for this crucial initiative [18, 19].

As an AU regulatory agency, the AMA aims to improve the harmonization of regulatory policies, thus resulting in an enabling environment for improved local medicine production and registration. This will facilitate healthy competition between pharmaceuticals, reduced cost of medical products, and easier access to safe and quality medicines resulting in increased revenue for NMRAs, particularly those with complete financial autonomy [36, 40, 43]. Furthermore, by serving as a continental regulatory body, the AMA can effectively regulate clinical trials for new therapies for infectious diseases in Africa, empower existing organizations such as the Pan African Clinical Trials Registry, and promote public participation in clinical trials. It will facilitate information sharing and ensure transparent clinical research in Africa [14, 37].

Several regional initiatives have also been active in Africa, as case studies of the need for a pan-African agency. For example, the East African Community Medicines Regulatory Harmonization has enabled joint assessments, leading to shorter timelines for medicine approval, as reported by assessors representing seven EAC authorities [10, 35]. In its pilot phase (2012–2017), the registration timeline of medical products was reduced by over 1 year, from 24 months to 8–12 months. Creating a pan-African platform may extend this benefit to other AU member states [10]. This study has also confirmed the AMA's intention to collaborate with existing NMRAs as opposed to concerns about replacement. It will address challenges faced by NMRAs of member states, including duplicative evaluation efforts and limited resources [14].

The AMA has achieved remarkable milestones through a combination of strategic efforts, which includes the appointment of a Special Envoy to advocate for the treaty among member states, regulation of traditional medicines, the alignment with the Partnerships, and the collaborative efforts of specialized health organizations [41, 44].

-

Recommendations

Due to the optimal health outcomes and benefits, governments should actualize commitments on the continental level, and all member states should adopt effective procedures in signing and ratifying the treaty and bring the commitment made by their respective governments to fruition. Additionally, further studies should explore why some African countries are not signing and ratifying the AMA treaty (Table 2).

-

Limitation of study

Although there was no quality assessment for each included study, we obtained most of them from peer-reviewed journals. On top of that, pieces of gray literature were also included, and the range of data used in this review applies the triangulation of data, which reduces the risk of publication bias and thereby improves the validity of the results [47].

Due to the lack of literature on the topic, the review could not retrieve information on factors that enabled the AMA and adequately cover some areas, such as the involvement of member states in AMA operationalization.

| Key areas | African Medicines Agency | European Medicines Agency | South-east Asia Regulatory Network | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involved countries | African Union member states (proposed) | European Union member states | 11 WHO Southeast Asian countries | |

| Medicine authorization (for human and veterinary use) | Influence on drug authorization | No, but the AMA can provide advice to the member states | Yes, through a recommendation to the EU Commission | No |

| Ability to issue drug authorization | No | No | No | |

| Inspection of manufacturers (Good Manufacturing Practices) | Yes, although the final approval of these manufacturers lies within the national authorities | No | No | |

| Quality control | Yes, through networking of quality control laboratories | Yes, through a reporting system & a rapid alert system | No | |

| Pharmacovigilance | No | Yes | Yes, through information exchange | |

| Postmarketing surveillance | Yes, through information exchange | Yes | Yes, through information exchange | |

| Clinical trial regulation | Yes, through regulatory guidance and/or coordination of regulatory oversight | Yes | No | |

| Capacity building | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

5 CONCLUSION

The value of AMA in achieving optimal health outcomes and the benefit it will bring to the African region cannot be overemphasized. The compliance of the present member nations with the treaty is an enabler to the conferred unity in the standards of national health systems. However, challenges such as poor data management, resource availability, low implementation of policies, and delays in regional and regulatory harmonization pose serious threats to the continental agency. The African region must surmount these challenges to achieve progress. The Agency will stand out as a strategic instrument to strengthen health systems and monitor the effectiveness of medicines, vaccines, and other health commodities. In addition, the AMA has the potential to facilitate the sharing of technical know-how and knowledge transfer among other continental initiatives such as the European Medicines Agency, South-East Asia Regulatory Network, and National Medicines Regulatory Agencies.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Adeniyi Ayinde Abdulwahab: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); supervision (equal); validation (equal); writing—original draft (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). Ukamaka Gladys Okafor: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); supervision (equal); validation (equal); writing—original draft (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). Damilola Samuel Adesuyi: Data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); methodology (equal); writing—original draft (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). Adriana Viola Miranda: Formal analysis (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); validation (equal); writing—original draft (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). Rashidat Onyinoyi Yusuf: Data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); validation (equal); writing—original draft (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). Don Eliseo Lucero-Prisno: Data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); validation (equal); writing—original draft (equal); writing—review and editing (equal).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This is a narrative review, hence, there was no need for ethical approval.

INFORMED CONSENT

Not applicable.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The authors confirm that all relevant data to this study are available in the article.