Are private hospital emergency departments in Australia distributed to serve the wealthy community?

Abstract

Objective

This study investigates the geographical distribution of private hospitals in Australian capital cities in relation to the Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage.

Methods

Using Geographic Information System analysis, the study examined how private hospitals are distributed across different socioeconomic quartiles, providing a comprehensive visualisation of health care accessibility.

Results

The results indicate an unequal distribution with a substantial concentration of private hospitals within the vicinity of communities classified in the highest socioeconomic classification. This raises significant concerns about health care equity, particularly in light of the increased strain on health care systems before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

This study underscores the need for targeted policy interventions to enhance the resilience and accessibility of the private health care sector, specifically targeting disadvantaged communities. It suggests that comprehensive, geographically-informed data is crucial for policymakers to make informed decisions that promote health equity in the postpandemic landscape.

Abbreviations

-

- ABS

-

- Australian Bureau of Statistics

-

- EDs

-

- emergency departments

-

- GIS

-

- Geographic Information System

-

- ICL

-

- The Inverse Care Law

-

- IRSD

-

- Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage

-

- PED

-

- Private Emergency Department

-

- QGIS

-

- Quantum Geographic Information System

-

- SA1

-

- Statistical Area Level 1

1 INTRODUCTION

Health care access is effectively defined as the degree to which individuals or communities are able to utilise appropriate health care services that meet their needs. The Behavioural Model of Health Services Use, initially introduced by Andersen in 1968, provides a foundational framework in this field. It identifies three core elements that influence health care utilisation: predisposing characteristics such as social class and education; enabling resources, which include factors like health care costs and insurance coverage; and perceived and clinical needs [1, 2]. This model distinguishes between potential access, which refers to the availability of resources facilitating health care use, and realised access, or the actual employment of health care services, a distinction that has guided numerous studies in understanding health care behaviours and needs [3, 4].

Expanding on Andersen's conceptualisation, McKinlay [5] examined the influence of sociodemographic, socio-psychological, and sociocultural factors alongside economic, geographic, and organisational elements in health care access and utilisation, setting a theoretical basis for later models. Penchansky and Thomas [6] further refined the concept of health care access by describing the alignment between patients and the health care system. Their model, building on Andersen's work, emphasises five dimensions of access: availability, accessibility, accommodation, affordability, and acceptability. These dimensions address various aspects of the patient-health care system interaction, underscoring the importance of ensuring equitable health care service distribution.

The Inverse Care Law, first articulated by Tudor Hart [7] in 1971, posits a paradoxical relationship between the availability of good medical or health care services and the actual need for them within the population. According to this principle, those who need health care services the most, typically individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds or residing in underprivileged areas, are often the ones with the least access to high-quality health care. Conversely, those with the slightest necessity for medical services, often individuals from higher socioeconomic groups with better overall health, have the most access to superior health care resources. This concept highlights a fundamental inequity within health care systems, where resources are not always allocated according to need but rather influenced by factors such as income, education, and geographical location. The Inverse Care Law concept underscores the challenges in achieving equitable health care, emphasising the need for targeted policies and interventions that specifically address the disparities in health care access and quality experienced by the most vulnerable segments of the population.

Australia's Medicare system is a foundational pillar of the country's health care infrastructure, offering a universal health scheme to its residents. Established in 1984, Medicare ensures that all Australians have access to a wide range of health and hospital services at little or no cost. It is funded through the country's tax system, which includes a Medicare levy based on individual income levels, to ensure the sustainability and accessibility of health care services [8, 9].

Medicare covers various aspects of health care, including treatment by doctors, specialists, and other health care professionals, hospital care, and, in some cases, prescription medicines and allied health services. Notably, Medicare is designed to provide coverage for both public and private patients in public hospitals, allowing individuals the freedom to choose their preferred health care providers within the public system [9].

One of Medicare's critical features is its role in complementing, rather than replacing, private health insurance. While Medicare offers broad coverage, private health insurance provides additional benefits, such as access to private hospitals, shorter waiting times for elective surgeries, and services that Medicare does not cover, including dental and optical care [10]. This dual system aims to balance the demand between public and private health care services, thereby enhancing the overall efficiency and quality of health care across Australia.

Despite its comprehensive coverage, the Medicare system faces challenges, particularly in funding and resource allocation, to meet the growing health care needs of Australia's population. These challenges underscore ongoing discussions among policymakers, health care providers, and the public on how to adapt and sustain the Medicare system for future generations, ensuring that it continues to provide equitable and quality health care for all Australians [11-13].

The private health care sector, comprising nongovernmental entities such as private hospitals, clinics, and specialists, plays an essential role in complementing the public health care system. Often financed through private health insurance, these services are crucial for alleviating the strain on public hospitals by expanding health care capacity [8, 14]. Most private hospital insurance policies allow patients choose their doctor or specialist and receive treatment as a private patient in a private or public hospital. Around 2 in every 5 hospitalisations in Australia occur in a private hospital [15]. The private sector also adds a competitive element to health care, fostering improvements in service quality, efficiency, and patient satisfaction [16].

Access to private health care in Australia, while significantly contributing to the country's comprehensive health system, which encompasses hospitals and ancillary health options, is marked by several barriers that can limit utilisation for various population groups [8, 17]. These barriers are multifaceted, encompassing economic, geographic, and systemic factors that collectively shape an individual's ability to seek and receive private health care services [8]. The most pronounced barriers to accessing private health care in Australia are economic. The cost of private health insurance premiums has been steadily increasing, often outpacing inflation and wage growth. For many Australians, especially those from lower-income brackets, the rising cost of premiums makes private health insurance unaffordable. Data shows that more than 55% of the Australian population held private health insurance in 2023, representing a total of 14.7 million individuals [18]. Geographic disparities significantly impact access to private health care services in Australia. Private health care facilities, including hospitals and specialist clinics, are predominantly located in urban and affluent areas. This distribution presents a significant challenge for individuals living in rural or remote regions where such facilities are scarce or nonexistent. Consequently, residents in these areas may have to travel long distances for health care, incurring additional costs and inconvenience, which can deter them from seeking private health care services. Furthermore, there is often a perception that private health care is exclusively for the wealthy, detering middle and lower-income individuals from considering it a viable option. This has resulted in individuals in disadvantaged or less affluent areas relying more on public health care services. Lastly, cultural barriers, including language differences and varying health beliefs, further complicate the accessibility landscape for Australia's culturally diverse population.

While Australia's health care system includes both public and private sectors, there is a significant research gap in understanding how these sectors interact and the resulting disparities in access and quality of care. Specifically, there is limited research on how socioeconomic and geographic factors influence the distribution of health care resources between public and private facilities. Additionally, the impact of private health care availability on public health outcomes, particularly in underserved rural and remote areas, remains underexplored. In conclusion, while Australia's private health care system offers significant benefits to those who can access it, addressing the current barriers is crucial to ensuring equitable health care for the entire population. Bridging these gaps requires concerted efforts from the government, the private health sector, and communities to make private health care more accessible and inclusive.

This study aims to investigate whether wealthy populations are predominantly located close to private health care facilities with emergency departments (EDs) by analysing the geospatial distribution of these facilities based on the Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage (IRSD) and age group.

2 METHODS

The study utilised data from the latest 2021 Census, specifically the Statistical Area Level 1 (SA1) level data on population and IRSD, providing insights into the socioeconomic distribution within the study area. SA1 represents the smallest geographical unit in the census data, encompassing a population range of 200−800 individuals. IRSD is a statistical index used in Australia to rank areas according to their level of economic and social disadvantage. The study also incorporated another data set, the general community profile from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), which includes information on the population's age distribution within each SA1. Population data were extracted and categorised into two age groups: adults (15–64 years), and seniors (65+ years). These specific age ranges were chosen to examine the accessibility of health care services across age groups and to gain insights into the health care utilisation patterns of adults and seniors. Previous research has highlighted the significance of these age groups in terms of their health care needs and public service utilisation [19].

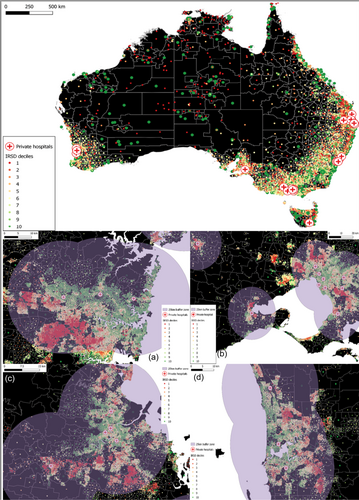

2.1 Private hospitals with ED

The study focused on private hospitals with a stand-alone ED, where the health care facilities do not share their structure with another public hospital, in the Australian capital cities: Melbourne in Victoria (VIC) (Figure 1); Adelaide in South Australia (SA); Sydney in New South Wales (NSW) (Figure 1); Brisbane in Queensland (QLD) (Figure 1); Hobart in Tasmania (TAS); Perth in Western Australia (WA) (Figure 1). However, Canberra in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and Darwin in the Northern Territory (NT) were not included in the study as no stand-alone private hospital with an ED was found.

2.2 Data extraction and analysis

To assess PED accessibility, geographic and socioeconomic data were integrated into the Quantum Geographic Information System (QGIS; version 3.24) software for spatial analysis. A 25 km buffer zone was established around each PED, and all SA1 centroids falling within this buffer were included in the study set. Previous studies assessing the spatial accessibility of health care services by Euclidean distances have classified distances >25 km from hospitals and emergency access as remote from health care services [19, 20].

Each SA1 centroid in the study set was then linked to the closest hospital. The distance between SA1 centroids and hospitals was calculated as the direct line distance, considering that all hospitals were situated within high-density road networks, allowing for a reasonable estimation of travel distance. Data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel (version 2205; Microsoft) to confirm no duplicate entries or missing values. Finally, tables, charts, and graphs were created to better visualise the results.

The study used publicly accessible data from the ABS and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) websites [21]. Hence, no ethical approval was required. Exemption from ethics review was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Western Australia (Approval number: 2021/ET000358).

3 RESULTS

The study integrated the population distribution across age categories (15–64 years, and 65+ years), at distances up to 25 km from each PED.

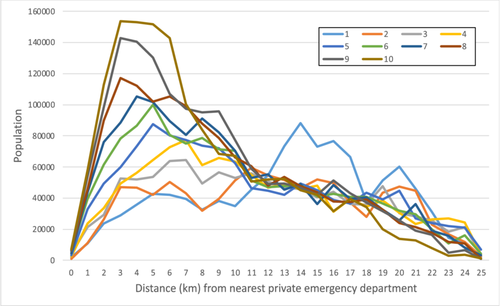

3.1 Population distribution

The analysis suggests that the spatial positioning of PEDs in the Australian capital cities significantly favours wealthier communities. For people living in immediate proximity (within 1 km) of a PED, the least socioeconomically disadvantaged group (IRSD rank 10) has the highest population (n = 7277). A similar trend prevails for individuals living within 25 km of PED. Moreover, the highest population proportions for both the most disadvantaged (IRSD decile 1) and least disadvantaged (IRSD decile 10) groups appear at distances of 3 km and 14 km. This is evident with population proportions reaching 153,767 for the least disadvantaged and 88,338 for the most disadvantaged group. The least disadvantaged groups remain dominant at virtually all distances. Interestingly, population numbers for both extremes of the IRSD scale seem to decrease after 15 km from PED. This may indicate that fewer individuals reside in these more distant areas regardless of socioeconomic status (SES) (Figure 2).

3.2 Age groups

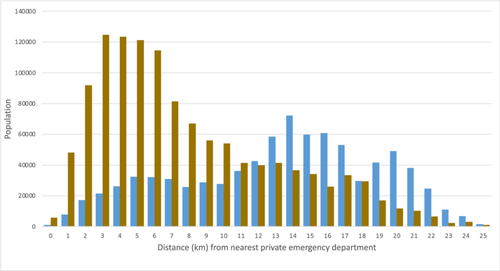

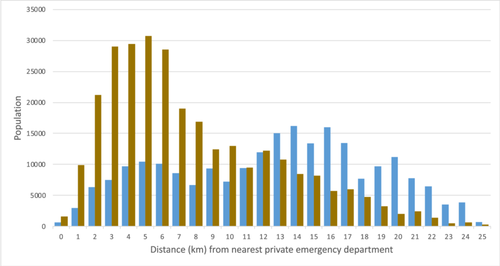

In the 15–64 age group, a noticeable trend emerges whereby there is a consistent increase in population numbers as we progress from the most disadvantaged to the least disadvantaged group, at virtually all distances from PED (Figure 3). Specifically, for the most proximal group, those living within 1 km, the most socioeconomically disadvantaged group has a population of 1217, while the least disadvantaged group has a population of 5698 (Table 1). The data peaks at 124,780 individuals in the least disadvantaged group (IRSD rank 10) living 3 km away from PED. A similar trend emerges within the 65 and above age category (Figure 4). The numbers generally grow with decreasing levels of socioeconomic disadvantage at all proximities. In the case of those living within 1 km, the most socioeconomically disadvantaged have a population of 654, while the least disadvantaged have a population of 1579 (Table 2). The apex of the population counts in this age bracket is observed at 30,691, corresponding to the least disadvantaged situated 5 km from PED (Figure 4).

| 15–64 age group | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| 0 | 1217 | 466 | 3518 | 1935 | 2631 | 5308 | 3725 | 5256 | 4686 | 5698 |

| 1 | 7746 | 8785 | 17,539 | 19,035 | 27,637 | 32,714 | 35,259 | 37,927 | 43,756 | 48,000 |

| 2 | 17,253 | 20,292 | 23,389 | 27,547 | 39,772 | 50,076 | 61,364 | 74,516 | 79,977 | 91,750 |

| 3 | 21,584 | 37,017 | 42,480 | 38,951 | 48,681 | 63,025 | 72,376 | 95,507 | 116,112 | 124,780 |

| 4 | 26,309 | 36,162 | 41,600 | 43,997 | 57,855 | 69,503 | 85,834 | 90,144 | 114,907 | 123,537 |

| 5 | 32,463 | 32,615 | 41,748 | 50,113 | 69,656 | 81,887 | 82,382 | 81,869 | 105,016 | 121,073 |

| 6 | 32,072 | 36,816 | 49,082 | 58,393 | 63,028 | 64,517 | 71,399 | 84,986 | 85,391 | 114,359 |

| 7 | 30,901 | 32,154 | 51,279 | 63,156 | 62,015 | 59,827 | 64,961 | 80,464 | 78,233 | 81,411 |

| 8 | 25,762 | 23,863 | 39,017 | 48,396 | 58,867 | 62,762 | 74,031 | 71,888 | 76,616 | 66,898 |

| 9 | 28,764 | 31,615 | 45,310 | 51,869 | 56,721 | 58,203 | 67,550 | 63,821 | 78,673 | 56,122 |

| 10 | 27,623 | 42,122 | 41,773 | 51,079 | 49,373 | 57,183 | 57,701 | 54,833 | 64,216 | 54,094 |

| 11 | 36,107 | 47,302 | 45,632 | 43,690 | 36,675 | 40,693 | 42,268 | 49,181 | 47,494 | 41,309 |

| 12 | 42,550 | 43,369 | 40,823 | 37,744 | 36,355 | 37,317 | 43,952 | 38,886 | 39,635 | 39,874 |

| 13 | 58,437 | 42,486 | 37,834 | 39,149 | 33,931 | 38,975 | 36,244 | 43,005 | 38,786 | 41,357 |

| 14 | 72,162 | 37,978 | 36,719 | 37,661 | 40,957 | 39,273 | 40,298 | 38,455 | 38,528 | 36,585 |

| 15 | 59,826 | 42,591 | 33,943 | 39,754 | 37,699 | 34,333 | 29,620 | 35,776 | 34,529 | 34,093 |

| 16 | 60,782 | 40,902 | 36,575 | 25,915 | 31,931 | 34,320 | 40,753 | 32,130 | 42,841 | 26,061 |

| 17 | 52,981 | 30,400 | 28,464 | 32,888 | 30,275 | 33,860 | 33,178 | 31,535 | 36,589 | 33,447 |

| 18 | 29,721 | 22,756 | 28,714 | 28,527 | 35,147 | 33,786 | 33,915 | 32,823 | 31,586 | 29,396 |

| 19 | 41,598 | 34,825 | 39,689 | 31,920 | 31,709 | 29,555 | 27,091 | 27,028 | 26,546 | 16,902 |

| 20 | 49,154 | 38,615 | 24,420 | 24,590 | 37,495 | 26,395 | 21,910 | 19,742 | 21,850 | 11,890 |

| 21 | 38,212 | 36,148 | 22,581 | 19,134 | 22,437 | 24,532 | 29,919 | 17,448 | 15,677 | 10,394 |

| 22 | 24,698 | 17,175 | 20,719 | 21,602 | 19,957 | 16,938 | 15,831 | 14,491 | 13,648 | 6443 |

| 23 | 11,045 | 12,747 | 14,332 | 21,283 | 18,000 | 8937 | 12,925 | 9914 | 4183 | 2447 |

| 24 | 6926 | 9408 | 17,167 | 20,292 | 17,552 | 13,431 | 7069 | 9020 | 5571 | 3137 |

| 25 | 1530 | 1825 | 3229 | 2968 | 5432 | 3308 | 2612 | 821 | 801 | 1087 |

- Note: 0 represents 0–1 km (but not including 1 km), and 25 represents 25–26 km (but not including 26 km).

- Abbreviation: IRSD, Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage.

| 65+ age group | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| 0 | 654 | 587 | 720 | 590 | 495 | 1259 | 899 | 1303 | 1289 | 1579 |

| 1 | 2943 | 2498 | 3793 | 4581 | 5270 | 6693 | 8601 | 7897 | 10,312 | 9884 |

| 2 | 6346 | 5997 | 6051 | 6015 | 9611 | 11,609 | 14,514 | 15,235 | 18,357 | 21,222 |

| 3 | 7470 | 9905 | 10,222 | 10,545 | 11,143 | 15,374 | 16,212 | 21,549 | 26,842 | 28,987 |

| 4 | 9712 | 10,430 | 10,467 | 12,412 | 15,495 | 16,954 | 19,588 | 22,139 | 25,675 | 29,411 |

| 5 | 10,417 | 9628 | 12,016 | 14,462 | 17,967 | 18,223 | 19,241 | 19,989 | 25,314 | 30,691 |

| 6 | 10,108 | 13,638 | 14,749 | 14,372 | 17,231 | 15,949 | 18,052 | 20,333 | 21,457 | 28,517 |

| 7 | 8561 | 10,860 | 13,357 | 14,120 | 15,393 | 15,348 | 15,623 | 18,464 | 19,133 | 19,029 |

| 8 | 6696 | 7940 | 10,489 | 12,821 | 14,785 | 15,801 | 17,221 | 15,876 | 18,510 | 16,887 |

| 9 | 9371 | 7778 | 11,387 | 14,004 | 15,462 | 13,238 | 14,608 | 14,834 | 17,026 | 12,415 |

| 10 | 7222 | 9210 | 11,074 | 12,565 | 13,216 | 13,381 | 12,798 | 11,387 | 13,271 | 12,975 |

| 11 | 9410 | 12,167 | 10,206 | 11,240 | 9596 | 10,518 | 10,815 | 11,372 | 11,408 | 9475 |

| 12 | 11,964 | 11,294 | 9972 | 8843 | 8547 | 9616 | 11251 | 9233 | 9363 | 12,227 |

| 13 | 15,037 | 9335 | 9307 | 9773 | 8126 | 8663 | 9068 | 10,658 | 10,707 | 10,806 |

| 14 | 16,176 | 8506 | 8897 | 7983 | 8437 | 9458 | 8713 | 9149 | 8208 | 8449 |

| 15 | 13,373 | 9492 | 6651 | 8353 | 7340 | 6960 | 6609 | 7951 | 7629 | 8178 |

| 16 | 15,961 | 8891 | 7565 | 5395 | 6801 | 8467 | 7743 | 5858 | 8431 | 5682 |

| 17 | 13,446 | 6804 | 7807 | 6716 | 6327 | 7061 | 6241 | 5891 | 6375 | 5995 |

| 18 | 7726 | 5073 | 7260 | 5999 | 8393 | 6913 | 6673 | 6287 | 5524 | 4747 |

| 19 | 9671 | 8459 | 8143 | 6466 | 7286 | 6900 | 5500 | 5563 | 5173 | 3245 |

| 20 | 11,189 | 8831 | 5881 | 5886 | 7352 | 5377 | 3757 | 4407 | 3764 | 1992 |

| 21 | 7792 | 8584 | 5695 | 4304 | 4581 | 5125 | 6283 | 4024 | 3288 | 2399 |

| 22 | 6442 | 5945 | 5015 | 4692 | 3948 | 3020 | 3336 | 3408 | 2927 | 1394 |

| 23 | 3490 | 4153 | 4166 | 5606 | 3890 | 2063 | 2754 | 1886 | 602 | 530 |

| 24 | 3884 | 2530 | 4182 | 4065 | 3560 | 2750 | 1245 | 1688 | 1112 | 611 |

| 25 | 732 | 672 | 635 | 571 | 1318 | 841 | 694 | 161 | 117 | 271 |

- Note: 0 represents 0–1 km (but not including 1 km), and 25 represents 25–26 km (but not including 26 km).

- Abbreviation: IRSD, Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage.

4 DISCUSSION

This study aimed to scrutinise the distribution of PEDs within Australian capital cities, focusing primarily on the surrounding area-level SES and employing Geographic Information System for detailed visual comprehension. Health affordability emerges as a central concern globally, influencing individuals' and communities' well-being and quality of life through the prism of medical service costs, insurance coverage, and access to quality care. It underlines the need for all individuals to have a fair opportunity to reach their full health potential, regardless of social, economic, or environmental circumstances [22].

The study further revealed accessibility variations across age groups, with both the adult (15–64 years) and senior (65+ years) cohorts experiencing enhanced access to PEDs amidst decreasing socioeconomic disadvantages. This trend suggests a systemic advantage that might influence overall health outcomes for these demographics. It becomes crucial to factor in these age groups' specific health care needs and utilisation patterns, particularly as older adults often necessitate more immediate health care interventions.

The analysis illuminated a clear pattern: individuals residing in less socioeconomically disadvantaged areas (highest IRSD decile) enjoy closer proximity to PEDs and constitute the highest population counts within a 1−25 km radius. This trend exemplifies the Inverse Care Law's manifestation within the Australian context, suggesting wealthier populations have more accessible emergency health care services. The findings align with the wealth-health gradient proposed by Frijters [23], who assert that wealthier individuals have better health outcomes because they have superior access to health care resources. Previous research also highlighted that health care accessibility is a multifaceted issue shaped by various socio-demographic elements [24]. Yet, it is also noteworthy to observe the decrease in population counts for both extremes of the IRSD scale beyond 15 km from private hospitals. This trend may point to other noneconomic factors influencing hospital distribution, such as private insurance availability, population density and urban-rural divides [25, 26]. Consequently, it suggests that the relationship between private hospital distribution and wealth distribution may be interwoven with other socio-demographic factors, illustrating the multidimensional nature of health care accessibility.

4.1 Implications for equity and policy

The findings underscore a pressing need for policy interventions to bridge health care accessibility disparities. The prevailing PED distribution not only mirrors but may also intensify existing inequalities, favouring wealthier demographics over those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and remote locales. Such an uneven distribution can significantly affect the affordability of PED for individuals of lower SES, supporting earlier research conducted by Davis [27], which examined the inequities in health care access. While access does not equate to affordability directly, the concentration of PED in higher SES neighbourhoods suggests a business model targeted towards patients who can afford the higher costs associated with private health care. This point aligns well with the argument of Quek [28], who indicates that the market-driven nature of private health care often overlooks the needs of those who are unable to pay. Furthermore, the results demonstrate that the challenges posed by affordability are not a distant problem but can be found within a radius as small as 0–1 km, supporting the argument by Singh [29] that even minor geographical differences can produce significant disparities in health care affordability. Addressing these disparities necessitates strategic planning in establishing new PED facilities and revising transportation and referral systems to foster equitable access. Moreover, the necessity for a nuanced health care planning approach that encompasses socioeconomic and age-related factors is evident. Policymakers are prompted to devise targeted strategies to mitigate barriers encountered by socioeconomically disadvantaged groups and older adults, potentially through subsidised PED access for low-income individuals or enhanced public transportation systems to bolster accessibility for remote residents.

A comparison with global examples highlights the effectiveness of universal health care systems in mitigating these disparities. For instance, the United Kingdom's National Health Service (NHS) provides a model where universal health care funded through taxation has significantly reduced disparities in health care access, ensuring that even the poorest segments of the population can access high-quality health care without financial barriers [30]. This underscores the potential for policy interventions to reduce inequities in health care accessibility and affordability.

4.2 Health equity considerations

The emergence of health equity as a pivotal component of global health policy and planning accentuates the necessity for all individuals to attain their full health potential, unhampered by social, economic, or environmental barriers. The alignment with the wealth-health gradient suggests that superior health care access among wealthier individuals directly correlates with better health outcomes. However, the noted decrease in population counts beyond 15 km from PEDs invites further investigation into noneconomic factors influencing health care distribution, such as population density and urban-rural divides. Overcoming the challenges of establishing private health care institutions in economically disadvantaged areas requires a collaborative effort involving government incentives, community engagement, and innovative business models to ensure culturally competent and widely accepted health care services. By tackling the inequalities in health care access, Australia can pave the way toward a more equitable and healthy future for all its citizens, irrespective of their SES.

4.3 COVID-19 and equity

In Australia, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted several critical issues regarding health equity. While Australia's health care system is robust by international standards, the pandemic has revealed vulnerabilities, particularly in access to care and health outcomes for Indigenous populations, individuals living in remote and rural areas, and socioeconomically disadvantaged groups [31, 32]. For example, the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines and the ability to access testing and treatment facilities were not uniform across the country, often reflecting broader issues of health care accessibility [33]. Remote and rural communities, as well as Indigenous Australians, faced significant barriers due to geographic isolation, limited health care infrastructure, and systemic socioeconomic disadvantages.

Moreover, the pandemic has spotlighted the mental health crisis, exacerbating issues such as anxiety, depression, and other mental health conditions across all demographics, with notably higher impacts on populations already experiencing health inequities [34]. The increased demand for mental health services has further strained the existing health care resources, pushing the need for an equitable distribution of mental health support services. The post-COVID-19 landscape has further highlighted health equity issues, revealing and exacerbating existing disparities. The spatial alignment of PEDs with wealthier communities within Australian capitals reveals a pattern consistent with previous research, emphasising the impact of socioeconomic standing on health care affordability and accessibility.

4.4 Limitations and future studies

The study's focus is exclusively on spatial accessibility to private hospitals. Factors such as service affordability, quality of care, or specialist availability are not encompassed within the scope of this research. The analysis provides a cross-sectional portrayal of the current situation.

Longitudinal assessments could provide valuable insights into how changes in health care accessibility and socioeconomic conditions over time impact patient outcomes. Additionally, qualitative studies focusing on patient experiences would offer a deeper understanding of the personal and social factors influencing health care access and affordability. These studies could explore the lived experiences of individuals from various socioeconomic backgrounds, shedding light on the specific barriers they face and the coping strategies they employ. Such research would enhance our understanding of the complex dynamics at play and inform the development of more effective and equitable health care policies.

5 CONCLUSION

In conclusion, while Australia's private health care sector is an integral part of the national health system, accessibility to private health care is significantly influenced by geographic location, SES, and health insurance coverage. The IRSD serves as a valuable indicator for understanding the intricate relationship between private health care accessibility and socioeconomic disadvantage. To address these disparities, there is an urgent need for robust health policies that promote a more equitable distribution and integration of private health care facilities across the country. These policies should ensure equal access to health care services regardless of SES or geographical location, particularly in light of the challenges highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Furthermore, special emphasis must be placed on enhancing health care accessibility in rural and remote areas, where private health care services are markedly underrepresented. This could involve strategic planning to establish new health care facilities, revise transportation and referral systems, and provide targeted subsidies for low-income populations. By prioritising these efforts, significant strides can be made in reducing health disparities and fostering a more inclusive health care system that meets the needs of all Australians, regardless of their socioeconomic or geographic circumstances.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Mazen Baazeem, Estie Kruger, and Marc Tennant wrote the main manuscript text. Mazen Baazeem analysed the data and prepared the tables and figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Exemption from ethics review was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Western Australia (Approval number—2021/ET000358).

INFORMED CONSENT

Not applicable.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support this study are available in the ABS website [https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/datapacks].