Neural correlates of heart rate variability in PTSD during sub- and supraliminal processing of trauma-related cues

Abstract

Background

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is characterized by dysregulated arousal and altered cardiac autonomic response as evidenced by decreased high-frequency heart rate variability (HF-HRV), an indirect measure of parasympathetic modulation of the heart. Indeed, subtle threatening cues can cause autonomic dysregulation, even without explicit awareness of the triggering stimulus. Accordingly, examining the neural underpinnings associated with HF-HRV during both sub- and supraliminal exposure to trauma-related cues is critical to an enhanced understanding of autonomic nervous system dysfunction in PTSD.

Methods

We compared neural activity in brain regions associated with HF-HRV in PTSD (n = 18) and healthy controls (n = 18) during exposure to sub- and supraliminal processing of personalized trauma-related words.

Results

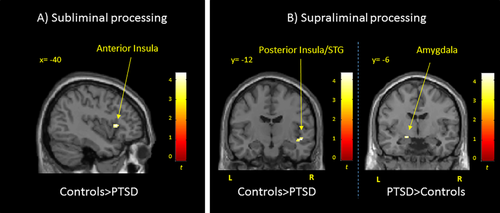

As compared to controls, PTSD exhibited decreased HF-HRV reactivity in response to sub- and supraliminal cues. Notably, during subliminal processing of trauma-related versus neutral words, as compared to controls, PTSD showed decreased neural response associated with HF-HRV within the left dorsal anterior insula. By contrast, during supraliminal processing of trauma-related versus neutral words, decreased neural activity associated with HF-HRV within the posterior insula/superior temporal cortex, and increased neural activity associated with HF-HRV within the left centromedial amygdala was observed in PTSD as compared to controls.

Conclusions

Impaired parasympathetic modulation of autonomic arousal in PTSD appears related to altered activation of cortical and subcortical regions involved in the central autonomic network. Interestingly, both sub- and supraliminal trauma-related cues appear to elicit dysregulated arousal and may contribute to the maintenance of hyperarousal in PTSD. Hum Brain Mapp 38:4898–4907, 2017. © 2017 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is characterized by dysregulated arousal [Etkin and Wager, 2007; Tull et al., 2007] as evidenced by measures of cardiac autonomic regulation [Berntson et al., 2008] at rest and in response to emotional stimuli [Buckley and Kaloupek, 2001; Pole, 2007]. Hyperarousal in PTSD has been linked to increased cardiovascular output, due to increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic control over the heart [Bernston et al., 1997; Blechert et al., 2007]. High-frequency heart rate variability (HF-HRV) is a noninvasive measure of the vagal influences mediating parasympathetic innervation of the heart [Bernston et al., 1997], reflecting the flexible adaptation of physiological and emotional responses to momentary needs [Appelhans and Luecken, 2006]. Critically, lower HF-HRV has been found in individuals with PTSD, both at baseline and in response to trauma-related cues [Cohen et al., 1997; Hauschildt et al., 2011].

In PTSD, studies examining subliminal processing of threat-related stimuli reveal differential responses of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), insula, amygdala, and brainstem to subliminal stimuli [Armony et al., 2005; Bryant et al., 2008; Kemp et al., 2009; Lanius et al., 2016; Rauch et al., 2000]. Notably, the mPFC, amygdala, and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) also show differential patterns of response to supraliminal stimuli [Sartory et al., 2013; Shin et al., 2005; Williams et al., 2006a]. Together, these brain areas form part of a network of regions, the Central Autonomic Network (CAN) (described in Thayer et al. [2009]), that plays a central role in connecting the central nervous system with the cardiac system [Benarroch, 1993]. Indeed, the Neurovisceral Integration Model [Thayer and Lane, 2000] proposes that HF-HRV may index a “core integration” system that integrates internal and environmental cues to regulate cognitive, behavioral, emotional and physiological expressions through brain–body connections. A meta-analysis investigating brain structures associated with HF-HRV [Thayer et al., 2012] identified key components of this network as active during related tasks. Specifically, whereas the amygdala and the ventral mPFC were active across tasks, the rostral mPFC was related specifically to emotion tasks and the left putamen to cognitive tasks. A subsequent meta-analysis [Beissner et al., 2013] identified the amygdala, the anterior and posterior insula, and the midcingulate cortex, as core areas of the CAN active across tasks and neuroimaging modalities (fMRI and PET).

Although several studies point to dysregulated autonomic responses to supraliminal trauma-relevant stimuli in PTSD, it remains unknown whether subliminal stimuli can affect HF-HRV in PTSD and whether hyper-responsivity to subliminal threat-related cues may contribute to dysregulated arousal and hypervigilance. Indeed, altered arousal responses in PTSD may relate to subtle threatening cues in the environment, thus triggering dysregulation of the autonomic response, even without explicit awareness of the provocation stimulus.

Accordingly, the objective of this study was to compare the neural activity in cortical and subcortical regions in association with HF-HRV during supraliminally and subliminally presented personalized trauma-related cues in individuals with versus without PTSD. Here, we predicted that autonomic flexibility, as measured by HF-HRV, would be lower in individuals with PTSD, a pattern reflected in altered activity of brain areas associated previously with autonomic activity (including the amygdala, insula, basal ganglia, cingulum, and prefrontal cortex) and occurring in interaction with HF-HRV response. Moreover, we hypothesized that presentation of sub- versus supraliminal levels of exposure to threatening stimuli would reveal significant condition-related group differences in brain responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Thirty-six right-handed individuals were included in the study. Of these, 18 subjects had a primary diagnosis of PTSD, and 18 nontrauma exposed participants formed the comparison group. This sample was part of a larger sample reported in previous studies [Rabellino et al., 2015a, 2015b, 2016]. Eight PTSD participants and two healthy controls (three for the subliminal session) were not included in the current study due to unavailability of physiological data. Demographic and clinical characteristics are detailed in Table 1. All participants were administered the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; cut-off score ≥50; Blake et al. [1995]) and the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) [Bernstein et al., 2003]. In addition, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID-I) [First et al., 2002] was administered to assess comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders. Among PTSD participants, 7 (38.8%) had experienced a personal life threat or were witnesses to a violent death, 10 (55.5%) had experienced a personal threat to physical integrity, and 1 (5.5%) individual had sustained a serious injury. In addition, 15 (83.3%) PTSD participants had experienced childhood trauma. All PTSD patients were free of medications for at least six weeks before scanning, and no drug or alcohol use in participants with a history of substance abuse and/or dependence was present within the last 6 months before participating in the study. Subjects were excluded in case of psychosis, bipolar disorder, significant medical or neurologic conditions, history of head injury (loss of consciousness), and fMRI incompatibility. Control participants who met criteria for current or lifetime psychiatric disorders were excluded. The study was approved by the Health Sciences Research Ethics Board of Western University, Canada. All participants were recruited through community advertisements and provided informed written consent.

| PTSD (n = 18) | Controls (n = 18) | t test/χ2 (P) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) years | 38.4 ± 12.2 | 32.9 ± 11.9 | 0.179 | |

| Gender (F %) frequency | 61.1% | 50% | 0.502 | |

| Employment status (employed %) frequency | 64.7% | 83.30% | 0.208 | |

| CAPS score (mean ± SD) | 68.9 ± 11.25 | 0.89 ± 2.61 | <0.001** | |

| CAPS Re-experiencing (mean ± SD) | 22.78 ± 5.76 | 0.78 ± 2.36 | <0.001** | |

| CAPS Avoidance (mean ± SD) | 24.44 ± 5.51 | 0.11 ± 0.47 | <0.001** | |

| CAPS Hyperarousal (mean ± SD) | 21.67 ± 6.64 | 0 | <0.001** | |

| CTQ Emotional abuse score (mean ± SD) | 14.4 ± 5.6 | 6.7 ± 3.2 | <0.001** | |

| CTQ Physical abuse score (mean ± SD) | 9.7 ± 6.1 | 5.7 ± 1.7 | 0.012* | |

| CTQ Sexual abuse score (mean ± SD) | 13.3 ± 7.5 | 5.3 ± 1.2 | <0.001** | |

| CTQ Emotional neglect score (mean ± SD) | 14 ± 5.7 | 8.5 ± 3.7 | 0.002** | |

| CTQ Physical neglect score (mean ± SD) | 10.6 ± 5.1 | 6.4 ± 2 | 0.003** | |

| AXIS I comorbidity (current n [past n]) frequency (only PTSD group) | Major depressive disorder (8 [5]) | |||

| Dysthimic disorder (0 [3]) | ||||

| Panic disorder with agoraphobia (0[1]) | ||||

| Panic disorder without agoraphobia (1[1]) | ||||

| Agoraphobia without panic disorder (2) | ||||

| Social phobia (3) | ||||

| Specific phobia (1) | ||||

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder (1) | ||||

| Eating disorders (1[1]) | ||||

| Somatoform disorder (5) | ||||

| Lifetime history of alcohol abuse or dependence [8] | ||||

| Lifetime history of substance abuse or dependence [5] | ||||

- a *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Controls n = 17 for the subliminal condition (significant between-group differences were substantially identical comparing PTSD and control samples included for the subliminal condition).

Procedures

Experimental design

The experimental design was adapted from standard previously published fMRI methods [Liddell et al., 2005; Williams et al., 2004]. A block design was used to present word stimuli at two levels of awareness: subliminal stimuli were presented as eight consecutive 16 ms backward masked segments (mask duration 161 ms) [Liddell et al., 2005], supraliminal stimuli were presented for 500 ms [Felmingham et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2006b]. Sub- and supraliminal conditions were administered in two consecutive runs, counterbalanced across subjects, according to previously established methods [Felmingham et al., 2008]. The stimuli consisted of individualized trauma words, matched for letter/syllable length (see Supporting Information) and provided by the participants (words perceived as direct cue for trauma in PTSD patients or for a stressful experience in controls), alternated with neutral words (words that did not elicit any positive or negative reaction). Each stimulus was repeated five times in a fixed order to prevent anxiety elicited by traumatic stimuli [Bremner et al., 1999]. The duration of each block (lasting 12.5 s) ensured suitable time for HF-HRV analyses [Bernston et al., 1997]. Participants' task was to view the stimuli that were presented. In addition, to ensure continued attention of the participants, a recognition test (here called “button press task”) lasting 4,500 ms was introduced between stimulus presentation blocks. The inter-stimulus interval was jittered and ranged between 823 and 1,823 ms in the subliminal condition, and between 500 and 1,500 ms in the supraliminal condition (for a graphic detailed depiction of the experimental design, see Rabellino et al. [2016]). Each run started with 30 s of resting state as the implicit baseline (fixation cross). All stimuli were presented using E-Prime 2.0 (2007, Psychology Software Tools).

Heart rate data collection and heart-rate-variability analysis

Measurement of heart rate occurred for the whole scanning session using Powerlab 8/35 with LabChart 7 Pro (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA), via a pulse oximeter (200 Hz sampling rate) attached to the participants' left finger.

HF-HRV preprocessing

HF-HRV was calculated based on interbeat intervals extracted from the pulse oximeter data, and log transformed to yield an estimate of respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) which reflects the amplitude of heart rate fluctuations associated with breathing frequencies [Butler et al., 2006; Cacioppo et al., 1994]. RSA calculations from plethysmograph data are reliably and strongly related to those calculated from ECG in other studies [Giardino et al., 2002; Jennings et al., 1987]. Raw pulse oximeter data acquired throughout the task were band-pass filtered from 0.1–3 Hz to remove high-frequency noise and detrended. The peak of each heartbeat cycle was identified in the smoothed data and interbeat intervals (IBIs) were extracted. If IBIs were estimated to occur >1.6 s apart, a beat was assumed to have been missed, and a derivative-based estimation procedure was used to estimate the local max nearest to the mean IBI. If beats were detected <0.5 s apart, it was assumed that a spurious beat was detected and it was removed. Following recent publications suggesting that the time-course of RSA can be understood via time–frequency decomposition [Mager et al., 2004], IBI data from the entire task were subjected to a single continuous Morlet wavelet transform [Torrence and Compo, 1998], which yielded continuously changing point-estimates of power throughout the frequency spectrum over the time-course of the task. Data in the 0.18–0.4 Hz range (consistent with the frequency band in which parasympathetic activity has maximal influence over IBIs) were averaged for each sample to yield a running estimate of HF-HRV using the Matlab HRVAS toolkit [software developed by Ramshur J and downloadable at https://github.com/jramshur/HRVAS], which we have independently verified to provide similar HF-HRV estimates to other canonical software packages. RSA was calculated as log(HF-HRV). Trial- and condition-related averages were computed from these estimates.

Preparation of RSA data for RSA-fMRI analyses

To relate RSA to fMRI, running RSA time series were downsampled to yield one value at each TR (3,000 ms) of the functional acquisition of images during the whole block-design procedure. We averaged these estimates across subjects to yield mean RSA values per TR within each group, with the TRs forming the units of analysis. Given the nature of the data, nonparametric tests were used for comparisons among group–condition combinations (Friedman tests) followed by post-hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, adjusted for multiple comparisons.

fMRI data acquisition and analysis

fMRI data acquisition

The study was conducted on a 3.0 T whole-body MRI scanner (Magnetom Tim Trio, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) with a 32-channel head coil. High-resolution (1 mm) T1-weighted anatomical images were acquired at the beginning of each scanning session using a 3D- MPRAGE sequence (TR = 2,300 ms, TE= 2.98 ms, TI= 900 ms, flip angle = 9°, FOV (X, Y, Z) = 256 × 240 ×192 mm, acc. factor = 4). BOLD fMRI images were acquired with a gradient echo planar imaging (EPI) pulse sequence using an interleaved slice (64 slices of 2 mm thickness) acquisition order and tridimensional Prospective Acquisition Correction (3D-PACE). The EPI volumes were acquired with 2 mm isotropic resolution, FOV was 192 × 192 mm, 94 × 94 matrix, TR 3,000 ms, TE 20 ms, flip angle 90°. Head motion was minimized using cushions during scanning.

fMRI analyses

Preprocessing: Image processing and statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Parametric Mapping 8 (SPM8, Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK) implemented in MATLAB R2013a (Mathworks Inc., Sherborn, MA, USA). Images were realigned to the first volume collected, to correct for head-movement, normalized (2 × 2 × 2 mm3) to the echo-planar template of SPM in MNI space and spatially smoothed with an 8-mm full-width at half-maximum isotropic Gaussian kernel. All events were convolved with the standard hemodynamic (double-gamma) response function. Baseline responses were acquired from the initial 30 s of rest-period at the beginning of each run.

Single-subject level

At the single-subject level, the BOLD-response was investigated according to the GLM, including a set of regressors of interest representing each stimulus displayed (neutral and trauma-related words, button task) for each of the two runs separately (subliminal and supraliminal), as well as the mean centered HF-HRV (1 value *TR), all convolved with SPM's canonical double-gamma HRF. Additional regressors of no interest included 6 movement parameters obtained from spatial realignment and the first 4 s of each run to allow for adjustment of HR acquisition. To investigate the BOLD-response specifically inherent to the association with HF-HRV, we calculated design × HF-HRV interactions (neutral words × HF-HRV, trauma-words × HF-HRV) that were subsequently added to create a second model comprising all the regressors (trauma-related words, neutral words, button task, mean centered HF-HRV, neutral words × HF-HRV, trauma-words × HF-HRV, movement parameters). Subsequently, a single BOLD-response contrast map was created for simple main effects and for each combination of within-factors (e.g., subliminal trauma words versus neutral words) accounting for differences in the magnitude of the BOLD signal.

Group level

The individual images obtained from the trauma-related > neutral words contrast were carried on to the group level to perform second-level random effects (subjects nested with groups as random) analyses. Here, two (groups—PTSD vs. controls) by two (HF-HRV interaction—inclusion vs. exclusion) full-factorial analyses were performed for subliminal and supraliminal processing, respectively, to investigate main and interaction effects. Follow-up two-sample t tests were performed to investigate significant group differences in the BOLD signal specifically associated with HF-HRV response during subliminal and supraliminal processing of trauma versus neutral words. A priori region of interest analysis (ROI) approach was used to interrogate results on the basis of previous literature relative to the interaction between BOLD and HF-HRV. Specifically, 15-mm-radius spheres were used for the anterior (centered on MNI coordinates: −30, 26, 8) [Beissner et al., 2013] and posterior insula (center MNI: 42, −14, −8) [Critchley et al., 2000], and a 10-mm-radius sphere was used for the left amygdala (center MNI: −20, −6, −18) [Beissner et al., 2013]. Significant results were considered at a voxel-wise P < 0.05 FWE-corrected threshold within each ROI, adjusted for multiple comparisons (yielding P < 0.016 FWE-corrected).

Finally, regression analyses investigated the correlation between HF-HRV related brain responses and PTSD symptom severity within the PTSD group as measured by the CAPS (results shown at a threshold of P < 0.05 FWE-corrected whole-brain or within aforementioned ROIs and adjusted for multiple comparisons).

RESULTS

Cardiovascular Response (HF-HRV)

During subliminal processing, in comparison to controls, the PTSD group showed lower HF-HRV when processing neutral and trauma-related words [all χ2 (1) ≥ 21.000, all P ≤ 0.0001, PTSD < controls all P < 0.0001] (Fig. 1). During supraliminal processing, as compared to controls, the PTSD group showed lower HF-HRV, when processing trauma-related and neutral words (all χ2 (1) ≥8.048, all P ≤ 0.005, PTSD < controls all P < 0.0001; see Fig. 1).

Average HF-HRV in each condition during subliminal (SUB) processing and supraliminal (SUPRA) processing in the PTSD group (blue) and in the control (CNTR, red) group. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. *indicates significant between-group differences (adjusted for multiple comparisons).

Neural Correlates Associated With HF-HRV

Subliminal processing of trauma-related words

A significant Group × HF-HRV interaction was revealed in the left dorsal anterior insula. Post-hoc t tests indicated that, as compared to controls, the PTSD group exhibited decreased BOLD response in the dorsal anterior insula when considering brain activity associated with HF-HRV versus brain activity independent from HF-HRV (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Brain regions showing neural activity associated with HF-HRV in PTSD as compared to controls during (A) subliminal processing of trauma-related versus neutral words and (B) supraliminal processing of trauma-related versus neutral words. Results are shown at P < 0.05 FWE-corrected threshold, adjusted for multiple comparisons, within a priori ROIs. PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder group; STG = superior temporal cortex.

| Brain region | x | y | z | k | Z | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subliminal processing trauma>neutral words | |||||||

| CNTR > PTSD neural activity in interaction with HF-HRV > independent from HF-HRV | Dorsal anterior insula | −40 | 18 | 6 | 26 | 3.91 | 0.011* |

| Supraliminal processing trauma > neutral words | |||||||

| CNTR > PTSD neural activity in interaction with HF-HRV > independent from HF-HRV | Posterior insula/STG | 50 | −10 | −8 | 25 | 4.35 | 0.002* |

| PTSD > CNTR neural activity in interaction with HF-HRV | Amygdala | −18 | −6 | −12 | 14 | 3.81 | 0.006* |

- CNTR, controls; HF-HRV, high-frequency heart rate variability; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; STG, superior temporal gyrus.

- Results are reported below P < 0.016 FWE-corrected threshold within a priori ROIs (*). Coordinates are reported in the MNI space.

Supraliminal processing of trauma-related words

A significant Group × HF-HRV interaction was found in the posterior insular/superior temporal cortex. When considering neural activity associated with HF-HRV versus independent from HF-HRV, post-hoc t tests revealed decreased activity in the posterior insular/superior temporal cortex in PTSD as compared to controls. When considering brain activity associated with HF-HRV, in comparison to controls, the PTSD group showed increased response in the left centromedial amygdala (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Regression with symptoms

PTSD symptom severity as assessed by CAPS was found to correlate positively with neural activity associated with HF-HRV in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) during subliminal processing of trauma versus neutral words (Table 3). By contrast, PTSD symptom severity correlated negatively with neural response associated with HF-HRV in the dorsal anterior insula during the same condition. Finally, during supraliminal processing of trauma-related versus neutral words, PTSD symptom severity correlated positively with neural activity associated with HF-HRV within the left centromedial amygdala (Table 3).

| Brain region | x | y | z | k | Z | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subliminal trauma > neutral words | |||||||

| Positive correlation with CAPS | dlPFC | 56 | 22 | 34 | 76 | 5.11 | 0.026 |

| Negative correlation with CAPS | Dorsal anterior insula | −34 | 34 | 4 | 12 | 4.06 | 0.014* |

| Supraliminal trauma > neutral words | |||||||

| Positive correlation with CAPS | Amygdala | −26 | 0 | −20 | 15 | 3.89 | 0.007* |

- CAPS, Clinician Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale; CNTR, controls; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

- Results are reported below P < 0.05 FWE-corrected threshold whole brain, or below P < 0.016 FWE-corrected threshold within a priori ROIs (*). Coordinates are reported in the MNI space.

DISCUSSION

This study compared the neural correlates of HF-HRV in response to subliminal and supraliminal processing of personalized trauma-related words between individuals with and without PTSD. As a trauma-exposed control group was not included in this study, we cannot be certain that the results relate directly to PTSD diagnosis rather than to trauma exposure (see also Limitations section). In keeping with previous studies, as compared to healthy controls, individuals with PTSD showed decreased HF-HRV [Blechert et al., 2007; Buckley and Kaloupek, 2001; Chalmers et al., 2014; Pole, 2007; Sack et al., 2004; Thome et al., 2017]. Our study is novel, however, in revealing that among individuals with PTSD, this pattern of lower HF-HRV emerges even during subliminal processing. Critically, brain regions previously identified as key hubs of the CAN (see meta-analyses) [Beissner et al., 2013; Thayer et al., 2012] showed altered activation in association with HF-HRV in individuals with PTSD; these patterns were not apparent in controls, pointing to disease specificity. In comparison to controls, PTSD participants also showed decreased activation of the dorsal anterior insula in association with HF-HRV during processing of subliminal trauma-related versus neutral words, as well as decreased activation of the posterior insula in association with HF-HRV during supraliminal processing of trauma-related versus neutral words. Finally, increased activity of the left amygdala in association with HF-HRV emerged in PTSD as compared to controls during supraliminal processing of trauma-related versus neutral words. These results point toward a highly specific pattern of failure of parasympathetic arousal modification in PTSD when threatening stimuli are presented both over and under the threshold of awareness. These findings suggest strongly that better characterization of physiological arousal associated with altered brain activation in PTSD as compared to controls will be critical to elucidating the mechanisms underlying dysregulated affective reactivity so commonly observed in this disorder. In particular, the shutdown of vagal modulation, in concert with altered neural activations, may expose individuals with PTSD to emotion dysregulation in response to unconscious triggers in their environment, perhaps through altered awareness of internal stimuli and impairment of executive functions (e.g., attentional focus) [Aupperle et al., 2012].

Subliminal Processing of Trauma-Related Words

In PTSD as compared to controls, processing of subliminal trauma-related words elicited decreased neural activity in the left anterior insula associated with decreased HF-HRV. The insula is considered functionally related to interoceptive and emotional awareness in humans [Critchley et al., 2000; Critchley, 2009; Damasio, 1999], plays a key role in the detection of salient stimuli [Menon, 2011; Menon and Uddin, 2010], and is viewed as central to the regulation of autonomic function [Beissner et al., 2013; Gianaros et al., 2004; Nagai et al., 2010; Thayer et al., 2009]. Its role in excitatory versus inhibitory processes, however, remains debated [Ahs et al., 2009; Beissner et al., 2013; Gianaros et al., 2004; Lane et al., 2009]. Our finding of decreased neural activity associated with HF-HRV in the anterior insula suggests strongly disrupted insula involvement in the partial mediation of parasympathetic activity of the autonomic nervous system in PTSD. Here, a lack of awareness of visceral responses during exposure to triggering subliminal cues may result in a failure of parasympathetic modulation of the autonomic system in PTSD compared to controls. This reduced insula response may lead to decreased vagal control over the heart, with resulting physiological and emotional hyperarousal symptoms [Hauschildt et al., 2011; Nagpal and Gleichauf, 2013].

These findings reveal key abnormalities in the ability of individuals with PTSD to regulate autonomic response, particularly when processing subliminal traumatic cues. This, in turn, may result in an inflexible hyperarousal autonomic response in PTSD. Indeed, individuals with PTSD may perceive subliminal threatening stimuli in the environment, thus triggering autonomic reactions and quick responses to threat without conscious reflective awareness. Such a physically demanding state may prevent individuals with PTSD from flexibly maintaining the homeostasis of the autonomic system, resulting in negative consequences on behavior, autonomic balance, and, ultimately, health.

Supraliminal Processing of Trauma-Related Words

As compared to controls, the posterior insula (extending to the superior temporal lobe) showed decreased activity in association with HF-HRV in PTSD during supraliminal processing of trauma-related versus neutral words. The posterior insula has been linked to the sympathetic modulation of the heart [Beissner et al., 2013]. Our findings may relate specifically to PTSD and suggest an altered modulation of the sympathetic response while under threat in this population. In addition, these findings point to a possible functional distinction between the anterior and posterior insular regions during subconscious vs. conscious processing, respectively. Taken together, these findings point towards the urgent need for further research on the functional distinction of the anterior and posterior insula within the CAN during processing of conscious versus subconscious stimuli.

Another crucial node of the CAN, the left centromedial amygdala, showed increased BOLD response associated with HF-HRV during supraliminal processing of trauma-related cues in PTSD as compared to controls. The amygdala is considered a critical hub of the CAN through its bidirectional communication with other key regions (i.e., cingulate cortex, insula, and hypothalamus) involved in activation/suppression of heart rate response [Beissner et al., 2013; Benarroch, 1993; Gianaros et al., 2004; Thayer et al., 2012]. Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis [Beissner et al., 2013] suggests that the amygdala plays a dual role in sympathetic and parasympathetic regulation during emotion tasks. Another meta-analysis investigating the neural correlates of HRV found that the left amygdala is centrally involved in HRV response across different tasks [Thayer et al., 2012]. Moreover, in a pattern similar to that reported here, the left amygdala has been related to the HRV response [Beissner et al., 2013; Gianaros et al., 2004; Thayer et al., 2012] and to emotion regulation of consciously perceived negative affect cues [Morris et al., 1998; Williams et al., 2006a, 2006b]. Our results support further the notion that exaggerated neural activity in the amygdala is not only associated with the emotional dysregulation typically found in PTSD [Frewen and Lanius, 2006; Hopper et al., 2007; Lanius et al., 2010], but may also be associated with dysregulated parasympathetic components of the autonomic response. Here, we suggest that the connection proposed in previous meta-analyses between the amygdala and inhibitory/excitatory nuclei in the brainstem (nucleus tractus solitarius, caudal, and rostral ventrolateral medullary neurons) [Beissner et al., 2013; Thayer et al., 2012] may foster emotional and autonomic hyperarousal in PTSD with chronic consequences in response to stressful stimuli.

Correlation With PTSD Symptom Severity

The negative correlation between PTSD symptom severity as measured by CAPS and BOLD response in the dorsal anterior insula during subliminal processing, and the positive correlation between CAPS scores and BOLD response in the left amygdala during supraliminal processing in association with HF-HRV, suggest that the more severe PTSD symptomatology, the less the individual is able to adaptively modulate parasympathetic outflow during exposure to stressful stimuli, either subliminally and supraliminally, via key hubs of the CAN.

Moreover, the positive correlation of PTSD symptom severity with neural activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex associated with HF-HRV during subliminal processing points toward the compensatory role played by the prefrontal cortex as this region attempts to over-regulate an unbalanced autonomic and emotional response to trauma triggers in PTSD [Fonzo et al., 2016; Shaw et al., 2009; White et al., 2015].

Limitations

Limitations of this study include a relatively small sample size that prevents the ability to generalize the results to the PTSD population at large. Moreover, we did not include measures of state dissociation and flashbacks experienced during the scanning session. Furthermore, a third comparison group, including trauma-exposed individuals without PTSD would have allowed us to discern between potential confounding variables (e.g., trauma exposure versus PTSD symptomatology). In this study, however, we found that individuals who experienced traumatic events similar to those experienced by our PTSD sample (e.g., childhood physical and emotional abuse) met the criteria for other psychiatric disorders thus excluding them from this study.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, a pattern of altered activation of major CAN regions implicated in regulating autonomic function emerged among individuals with PTSD in association with HF-HRV. This pattern was apparent regardless of whether it was measured in response to subliminal processing of trauma-related words (decreased anterior insula) or during supraliminal processing of trauma-related words (decreased posterior insula and increased amygdala). As noted by previous authors [Park and Thayer, 2014], lower HRV (at rest) is associated with hypervigilant responses towards neutral cues in the environment. Accordingly, we suggest that our findings point towards aberrant neural mechanisms that together are responsible for the maintenance of autonomic hyperarousal, as exhibited by reduced variability of the cardiovascular response in PTSD as compared to controls. On balance, our findings suggest strongly the need for future research to include more than one measure of the biophysiological response to threat and fear in PTSD to more fully validate and elucidate the neural and physiological mechanisms underlying the stress response. Moreover, our results indicate that further investigation of subliminal stimuli is crucial to improve our understanding of the effects of trauma reminders occurring in everyday life beyond the level of conscious awareness. Practitioners and researchers alike will need to remain alert to PTSD symptoms involving altered autonomic responses triggered by subliminal threatening stimuli that arise as the result of biased attention to potential trauma cues in the environment.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflict of interest.