Communicating a diagnosis of Dravet syndrome to parents/caregivers: An international Delphi consensus

Abstract

Objective

Dravet syndrome is a developmental and epileptic encephalopathy characterized by drug-resistance, lifelong seizures, and significant comorbidities including intellectual and motor impairment. Receiving a diagnosis of Dravet syndrome is challenging for parents/caregivers, and little research has focused on how the diagnosis should be given. A Delphi consensus process was undertaken to determine key aspects for healthcare professionals (HCPs) to consider when communicating a Dravet syndrome diagnosis to parents/caregivers.

Methods

Following a literature search and steering committee review, 34 statements relating to the first diagnosis consultation were independent- and anonymously voted on (from 1, totally inappropriate, to 9, totally appropriate) by an international group of expert child neurologists, neuropsychiatrists, nurses, and patient advisory group (PAG) representatives. The statements were divided into five chapters: (i) communication during the first diagnosis consultation, (ii) information to be delivered during the first diagnosis consultation, (iii) points to be reiterated at the end of the first diagnosis consultation, (iv) information to be delivered at subsequent consultations, and (v) communication around genetic testing. Statements receiving ≥ 75% of the votes with a score of ≥7 and/or with a median score of ≥8 were considered consensual.

Results

The statements were evaluated by 44 HCPs and PAG representatives in the first round of voting; 29 statements obtained strong consensus, 3 received good consensus, and 2 did not reach consensus. The committee reformulated and resubmitted 4 statements for evaluation (42/44 voters): 3 obtained strong consensus and 1 remained not consensual. The final consensual recommendations include guidance on consultation setting, key disease aspects to convey, how to discuss genetic testing results, disease evolution, and the risk of SUDEP, among other topics.

Significance

It is hoped that this international Delphi consensus will facilitate a better-structured initial diagnosis consultation and offer further support for parents/caregivers at this challenging time of learning about Dravet syndrome.

Plain Language Summary

Diagnosis of Dravet syndrome, a rare and severe form of childhood-onset epilepsy, is often challenging to give to parents. This international study developed guidance and recommendations to help healthcare professionals better structure and personalize this disclosure. By following this advice, doctors can provide more tailored support to families, improving their understanding and management of the condition.

Key points

- Dravet syndrome is a rare developmental and epileptic encephalopathy characterized by drug-resistant, lifelong seizures and comorbidities.

- Giving this diagnosis is challenging, due to the large amount of information to be delivered and the difficulty of handling its challenging effect on families.

- Consensual statements provide healthcare professionals with pragmatic guidance for good communication around the diagnosis with parents/caregivers.

1 INTRODUCTION

Dravet syndrome is a developmental and epileptic encephalopathy of infantile onset caused in the majority of cases by pathogenic variants in the SCN1A gene, which encodes the alpha subunit of the NaV1.1 sodium channel.1, 2 This rare and severe condition is associated with drug-resistant, lifelong seizures and comorbidities of various degrees of severity. These include motor impairments such as gait difficulties and poor coordination, intellectual disabilities, speech delays, behavioral difficulties, sleep disturbances, and a heightened risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP).3 It has a premature mortality rate of 6%–18%, with SUDEP being the most common cause of death in children, followed by status epilepticus.3-5 Due to the broad spectrum of symptoms and its clinical evolution over time, managing this condition requires a team of multidisciplinary medical, paramedical, and social care professionals.6-8 As such, the role of the healthcare team is crucial, as parents/caregivers of young children with Dravet syndrome will experience high emotional and physical burden, but also a deterioration of their quality of life (e.g., psychosocial and financial difficulties or restriction of social activities).9-12

Receiving a diagnosis of Dravet syndrome is usually devastating for parents/caregivers.13, 14 Parents not only want their child's condition to be managed by an expert, but often depend on the healthcare team for information and support and rely particularly on appropriate communication skills, but also accountability and thoroughness by their child neurologist.15-17

In recent years, therapeutic and genetic advances18, 19 have enabled the development of national and international recommendations for the clinical management of Dravet syndrome,20-24 including recommendations for the assessment of patient and caregiver's quality of life.25 However, these recommendations20, 25, 26 have mainly looked at the clinical and therapeutic management of Dravet syndrome, and contain fragmented information on how to give the diagnosis to parents.

To fill this gap, a Delphi consensus was undertaken to enhance recommendations for existing disease management guidelines and to provide healthcare professionals (HCPs) with practical advice specifically related to the communication of a Dravet syndrome diagnosis. These recommendations include the consultation setting, initial information to be provided to parents/caregivers about the disease and its management, as well as communication modalities. To the best of our knowledge, our study is one of the first to focus solely on the communication of the diagnosis without entering into considerations of choice of treatment or personalized clinical management.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 The Delphi methodology

The Delphi method is an iterative consensus approach based on information collected from a panel of participants with expertise in a topic under consideration.27-31 In recent years, this approach has been widely used in epileptology32-36 and in research on Dravet syndrome.20, 25, 37-39 In accordance with international methodologies,28-30 our study was structured as a Delphi consensus conducted between April 2023 and February 2024 with international experts involved in Dravet syndrome management. Expert opinion was obtained during two rounds of scoring based on statements written by the expert authors of this study (see section Steering committee [SC] and statements). Participants indicated their level of agreement with the statements using a 9-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally inappropriate) to 9 (totally appropriate). There was no option of “no opinion.” The percentage of scores and medians were calculated for each statement separately in each of the two voting rounds.

A “strong consensus” was defined for a statement when ≥75% of the scores were ≥7 and the median score was ≥8. When only one of these two parameters was satisfied, the statement was considered to have obtained a “good consensus”.28, 29 Any other situation was considered as a “lack of consensus.”

2.2 Steering committee (SC) and statements

A multidisciplinary international SC with expertise in pediatric neurology, psychiatry, psychology, nursing, and patient advisory (i.e., the expert group of authors of this study) was formed. Statements for the first round of voting were formulated during three meetings. The proposed statements were based on international recommendations, literature on diagnostic communication about severe pediatric illnesses in general and Dravet syndrome in particular, and the clinical experience of the SC members (Figure S1).

2.3 Composition of the rating group

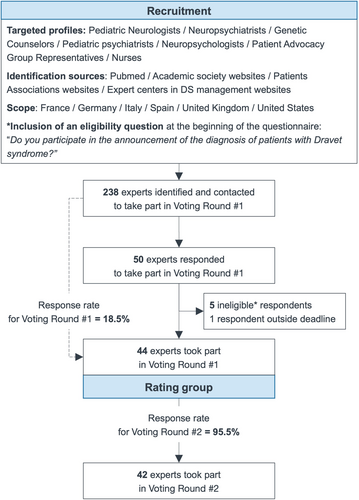

A carefully considered process was undertaken to select experts for the rating group who would be voting on the SC Delphi statements and giving them scores. To ensure that all experts had a high level of expertise in the management of Dravet syndrome and a strong international representation, they were identified via several sources: literature review via PubMed, professional, and patient association websites (i.e., Dravet Syndrome European Federation and Dravet Syndrome Foundation), and identification of expert centers via their professional websites. In terms of medical specialties, the targeted profiles were pediatric neurologists [the majority], neuropsychiatrists, genetic counselors, pediatric neuropsychiatrists, neuropsychologists, and nurses. Patient advisory groups (PAG) were also invited to participate, excluding the two PAGs already represented by the SC. The predetermined goal was to gather 10 voting experts from each of the six countries corresponding to the SC nationalities: France, Spain, Italy, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States, that is, 60 voting experts in the rating group. A filter question was included to ensure that participants had already taken part in at least one diagnostic conversation process for Dravet syndrome before voting could proceed (Figure 1).

Participants in the rating group remained anonymous throughout the process and had no interaction with the SC, whose members were excluded from voting on the Delphi statements.

2.4 Conduct of voting rounds

- Statements with a strong consensus (i.e., ≥75% of scores ≥7 and median ≥8) were validated and directly included in the final recommendation.

- Statements without consensus were either reformulated or modified based on voters' comments and submitted to voting round #2, or either left without consensus.

- Statements with a good consensus (i.e., ≥75% of scores ≥7 or median ≥8) were discussed and proposed for voting round #2 only if, after analyzing voters' comments, the SC found more agreeable wording.

Using the same individual e-mail system with personalized access to the survey site, voters in voting round #1 were invited to take part in voting round #2, this time for four statements, with no option of free-form comments. As predetermined by the SC, the process was stopped after two rounds.

2.5 Ethical aspects

This study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All personal data submitted for the study was separated from the results and anonymized in accordance with European data protection law (GDPR – General Data Protection Regulation). All voters were informed about GDPR prior to participating. Voters were asked at the end of round #2 if they wished to be acknowledged in the article (Table S1).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Composition of a rating group

Forty-nine experts responded to the questionnaire, five of whom failed the eligibility question and were excluded from the study. Of the 44 participants who took part in voting round #1, 42 responded to voting round #2, resulting in a response rate of 95.5% for the second round (Figure 2).

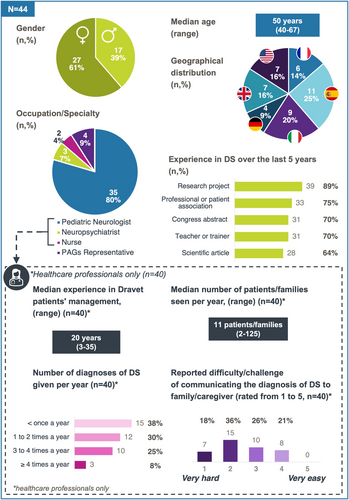

A summary of the characteristics of the rating group is shown in Figure 2. The number of participants per country ranged from 4 (9%, Germany) to 11 (25%, Spain). The vast majority (80%) of voters were pediatric neurologists, 7% were neuropsychiatrists, 4% were nurses and 9% were PAG representatives. Unfortunately, none of the clinical geneticist or counselor contacted accepted to take part in the rating group. These 4 PAG representatives came from four different countries. A significant proportion of respondents (93%) had conducted research on Dravet syndrome in the previous 5 years. The 40 HCPs in the rating group had a median experience of 20 years in managing Dravet syndrome patients, and they had followed a median number of 11 patients/families per year. Sixty-three per cent had given a diagnosis of Dravet syndrome to caregivers once a year or more, and 54% had found the diagnosis conversation process hard or very hard.

3.2 Consensus statements

The SC members proposed 34 statements divided into five topics relating to: (i) communication during the first diagnosis consultation, (ii) information to be delivered during the first diagnosis consultation, (iii) points to be reiterated at the end of the first diagnosis consultation, (iv) information to be delivered at subsequent consultations, and (v) communication around genetic testing.

After voting round #1, 29 out of the 34 statements achieved a strong consensus, 3 statements achieved a good consensus, and 2 statements did not achieve a consensus. Four statements were reformulated by the SC for voting round #2, and 1 statement from the 2 which did not achieve a consensus was not reformulated. After voting round #2, 3 of the 4 statements obtained a strong consensus, and the remaining statement did not obtain a consensus. In the end, 32 statements (94%) obtained a strong consensus, 1 statement (3%) reached a good consensus, and 1 statement (3%) did not reach consensus. The distribution of votes, medians, and results for each topic is given in Tables 1–3.

| Statements | %1-2-3 (n) | %4-5-6 (n) | %7-8-9 (n) | Median | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication during the first diagnosis consultation | 1 | Announcement of the diagnosis should be made by a clinician with expertise in Dravet syndrome who will be the patient's/parent's/caregiver's point of contact for at least the first few years of the child's life | 6.8% (3) | 13.6% (6) | 79.5% (35) | 8 | Strong consensus |

| 2 | In the first consultation, where possible, the presence of a nurse, psychologist, or junior doctor may be useful to give parents/caregivers additional points of contact, being mindful not to overwhelm them | 6.8% (3) | 25.0 (11) | 68.2% (30) | 8 | Good consensus | |

| 3 | Ideally, this first consultation should be promptly followed by other consultation(s) to review information and answer subsequent questions | 2.3% (1) | 13.6% (6) | 84.1% (37) | 9 | Strong consensus | |

| 4 | Allow sufficient time to be devoted to this first consultation | 0% (0) | 4.5% (2) | 95.5% (42) | 9 | Strong consensus | |

| 5 | If possible, an announcement of the diagnosis should be made at a dedicated time, in an outpatient setting (clinic room), preferably face-to-face, in the presence of the parents/caregivers, and avoiding any disturbance | 4.5% (2) | 2.3% (1) | 93.2% (41) | 9 | Strong consensus | |

| 6 | If possible, minor siblings should not be present during this first consultation | 11.4% (5) | 11.4% (5) | 77.3% (34) | 8 | Strong consensus | |

| 7 | The time taken and the choice of words to present each item of information should take into account parents'/caregivers' prior knowledge of the disorder and their level of education | 0% (0) | 4.5% (2) | 95.5% (42) | 9 | Strong consensus | |

| 8 | Dravet syndrome is a clinical diagnosis; the disorder can be discussed with parents/caregivers according to the child's clinical presentation before the genetic testing results are available | 4.5% (2) | 18.2% (8) | 77.3% (34) | 8 | Strong consensus | |

| 9 | Dravet syndrome is a spectrum disorder ranging from more to less severe presentation with an unpredictable course. The healthcare team should not be too pessimistic nor give rise to false hopes during this first consultation, and beyond | 9.1% (4) | 9.1% (4) | 81.8% (36) | 8 | Strong consensus | |

| Information to be delivered during the first diagnosis consultation | 10 |

During the first consultation, parents/caregivers should be given the following information regarding the disorder:

Explanation that it is a spectrum disorder, which means that severity can vary from person to person, but all patients experience these key characteristics. |

2.3% (1) | 6.8% (3) | 90.9% (40) | 9 | Strong consensus |

| 11 | During the first consultation, parents/caregivers should be informed that seizures are frequently triggered by stimuli, predominantly fever or temperature changes | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 100.0% (44) | 9 | Strong consensus | |

| Information to be delivered during the first diagnosis consultation | 12 | During the first consultation, parents/caregivers should be informed that seizures can be prolonged and given an explanation of the term “status epilepticus” | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 100.0% (44) | 9 | Strong consensus |

| 13 | During the first consultation, parents/caregivers should be given a written copy of an acute seizure management protocol, and their understanding of it should be validated. Ensure parents/caregivers have this protocol in place immediately following the first consultation | 2.3% (1) | 2.3% (1) | 95.5% (42) | 9 | Strong consensus | |

| 14 | During the first consultation, parents/caregivers should be informed about the most common seizure types at the patient's age and should be given advice on how to recognize new seizure types to report them to the child's healthcare team | 0% (0) | 9.5% (4) | 90.5% (38) | 8.5 | Strong consensus | |

| 15 |

During the first consultation, parents/caregivers should be offered the following information regarding treatment for Dravet syndrome:

How to administer an ASM, sharing potential issues and how to overcome them. |

0% (0) | 6.8% (3) | 93.2% (41) | 9 | Strong consensus | |

| 16 | During the first consultation, discuss first aid and risk related to epileptic seizures | 0% (0) | 4.5% (2) | 95.5% (42) | 9 | Strong consensus | |

| 17 | During the first consultation, the risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) should be discussed with parents/caregivers. If the clinician is of the opinion that it is not appropriate to discuss this at the first consultation, then discussing SUDEP at the earliest next opportunity is strongly recommended | 9.5% (4) | 11.9% (5) | 78.6% (33) | 8 | Strong consensus | |

| 18 | Given the relationship between SUDEP and generalized tonic–clonic seizures (GTCS), parents/caregivers should be informed about seizure detection/monitoring devices/baby monitors, but noting that any selected device should be individually tailored to the child and none are 100% precise, so close observation is always also required | 7,1% (3) | 16.6% (7) | 76.2% (32) | 8 | Strong consensus | |

| Points to be reiterated at the end of the first diagnosis consultation | 19 |

At the end of the first consultation, the clinician should emphasize the following:

Although the internet is a readily available source of information, it is important to receive information from reliable sources, ideally provided or recommended by the healthcare team |

0% (0) | 2.3% (1) | 97.7% (43) | 9 | Strong consensus |

| 20 | At the end of the first consultation, the clinician should offer parents/caregivers a timely next appointment (weeks) and clarify their preferred format (face-to-face or telemedicine) | 6.8% (3) | 6.8% (3) | 86.4% (38) | 9 | Strong consensus | |

| 21 | At the end of the first consultation, the clinician should provide parents/caregivers with their contact information (doctor and/or nurse) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 100.0% (44) | 9 | Strong consensus | |

| 22 | At the end of the first consultation, parents/caregivers should be given contact details of Dravet syndrome Patient Advisory Groups, together with disorder-specific materials if available — such as brochures/guides (or websites) | 2.3% (1) | 13.6% (6) | 84.1% (37) | 9 | Strong consensus | |

| 23 | At the end of the first consultation, parents/caregivers should be given the opportunity to invite other members of the child's support community to attend the next consultation | 9.1% (4) | 25.0% (11) | 65.9% (29) | 7 | Absence of consensus | |

| 24 | The child's primary care providers should be advised what information was given to the parents/caregivers during the first consultation | 6.8% (3) | 9.1% (4) | 84.1% (37) | 9 | Strong consensus |

- Note: %1-2-3 represents the percentage of votes ≤3; n represents absolute number. %4-5-6 represents the percentage of votes ≥4 and ≤6; n represents absolute number. %7-8-9 represents the percentage of votes ≥7; n represents absolute number. Total number of voters varied from 44 (voting round #1) and 42 (voting round #2, statements #14, #17, #18).

3.2.1 Communication during the first diagnosis consultation (9 statements)

Firstly, voters agreed strongly that giving the diagnosis should be made by a clinician with expertise in Dravet syndrome. Voters agreed with a good consensus that where possible, a nurse, psychologist, or junior doctor should also be present, being mindful not to overwhelm caregivers with too many professionals present. Voters strongly agreed that sufficient time should be taken in this first consultation and that if possible, the diagnosis should be made at a dedicated time, in an outpatient setting (clinic room), preferably face-to-face and avoiding any disturbance and without the presence of minor siblings if possible. Voters strongly agreed that the time taken and the choice of words used to present each item of information to parents/caregivers should consider their knowledge of the disorder and their level of education.

Strong consensuses were reached agreeing that Dravet syndrome is a clinical diagnosis that can be discussed with parents/caregivers according to clinical presentation before genetic test results are available and that Dravet syndrome is a spectrum disorder ranging from more to less severe presentation with an unpredictable course, implying that the healthcare team should not be too pessimistic nor give rise to false hopes to parents/caregivers during the first consultation and beyond.

Finally, the first consultation should be promptly followed by other consultation(s), to review information initially provided to parents/caregivers and answer subsequent questions (Table 1).

3.2.2 Information to be delivered during the first diagnosis consultation (9 statements)

All nine statements concerning information that should be given to parents/caregivers during the first consultation achieved a strong consensus. Voters agreed that such information should be: an explanation of the term “Dravet syndrome” —being a rare but severe and complex developmental and epileptic neurological disorder—; that the child's symptoms point to the diagnosis; that Dravet syndrome is a genetic condition but not necessarily hereditary (i.e., mutations arise de novo); that it is characterized by lifelong seizures and intellectual disability in addition to a range of other difficulties in various areas (language, motor skills, behavior, etc.) that evolve over time and are of variable severity; and that Dravet syndrome is a spectrum disorder and so, severity can vary from person to person, although all patients experience key characteristics.

Voters also agreed that in the first diagnosis consultation, parents/caregivers should be informed that seizures are frequently triggered by stimuli, predominantly fever or temperature changes, and that they can be prolonged; that parents/caregivers should be given an explanation of the term “status epilepticus” and a written copy of an acute seizure management protocol, validating their understanding of it and ensuring its immediate deployment. Voters also agreed that parents/caregivers should be informed about the most common seizure types according to the patient's age, and that they should be given advice on how to recognize new seizure types in order to be able to report them to the HCP.

Voters also achieved strong consensus agreement on the information to be given to parents/caregivers regarding Dravet syndrome treatment: the need for long-term treatment; the aim of such treatment – to prevent and reduce the frequency and duration of seizures; the possible need for multiple concurrent treatments, which might be different from or in addition to the treatment already in place (i.e., there are preferred medications for Dravet syndrome); the potential appearance of side effects related to anti-seizure medications (ASM); how to administer the ASM; and that certain ASMs should be avoided in Dravet syndrome (e.g., sodium channel blockers).

Strong consensus was also reached to having a discussion with parents/caregivers during the first diagnosis consultation about first aid and risk related to epileptic seizures. Importantly, voters strongly agreed that the clinician should discuss the risk of SUDEP with parents/caregivers during the first consultation. However, if the clinician feels that this discussion is not appropriate at the first consultation, experts strongly recommend discussing SUDEP at the earliest next opportunity.

Finally, given the relationship between SUDEP and generalized tonic–clonic seizures, voters agreed that parents/caregivers should be informed about seizure detection and monitoring devices and that any selected device should be individually tailored to the child as none are 100% precise, and therefore close observation is also required (Table 1).

3.2.3 Points to be reiterated at the end of the first diagnosis consultation (six statements)

Voters strongly agreed that the following points should be reiterated at the end of the first diagnosis consultation: that parents/caregivers are welcome to contact the healthcare team at any time; the importance of obtaining information only from reliable sources, ideally provided or recommended by the healthcare team; that parents/caregivers are given doctor/nurse contact information and contact details of a Dravet syndrome PAG, together with disorder-specific materials, if available. In addition, it was strongly agreed that the child's primary care providers should be advised what information was given to parents/caregivers at this first consultation, and that clinicians should offer parents/caregivers a timely next appointment (within weeks), clarifying parents'/caregivers' preferred format for this meeting (face-to-face or telemedicine). However, no consensus was reached on whether or not parents/caregivers should be given the opportunity to invite other members of the child's support community to attend the next consultation (Table 1).

3.2.4 Information to be delivered at subsequent consultations (six statements)

All statements relating to information to be delivered at subsequent consultations achieved strong consensus from the rating group. Voters confirmed that the second consultation should start by giving parents/caregivers the opportunity to recount key information discussed at the initial consultation and address potential questions; that clinicians should remind parents/caregivers of the emergency protocol/plan and the goals for seizure control.

Voters also agreed that the following information may be covered with parents/caregivers at subsequent visits: details about the different types of seizures, details about the treatment strategy and options (including sequence of treatments and dose escalation), details about additional therapeutic options (medication, diet), details about SUDEP, genetics of the disorder, and long-term outcomes and comorbidities.

Also, that intellectual disability – a well-established comorbidity – should be proactively discussed with parents/caregivers early in the course of the disorder, with notice that the child's development will be observed to identify potential concerns to allow for early intervention.

A strong consensus was obtained regarding information to be considered for patient monitoring: monitoring the child's development and educational needs, identification of additional patient-specific seizure triggers, advice to keep a calendar/diary of seizures, and guidance about the need for regular electroclinical monitoring, blood levels of ASMs, and routine blood tests.

Finally, voters strongly agreed that the remaining information to consider for these subsequent visits included a reminder about the importance of vaccinations and prevention of infections; enquiry about the development/behavior of the child and related concerns; discussion about working with educational institutions (nursery/school) for developmental assessment/special education services; enquiry about the well-being/psychological state of siblings and parents/caregivers; suggestion of psychological support for the family; information about any financial/social assistance available, including the supply of a social worker's contact information; and information about possible local rehabilitation services (Table 2).

| Statements | %1-2-3 (n) | %4-5-6 (n) | %7-8-9 (n) | Median | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | The second consultation should start by giving parents/caregivers the opportunity to recount key information discussed at the initial consultation and address their questions | 0% (0) | 6.8% (3) | 93.2% (41) | 9 | Strong consensus |

| 26 | Essential information that parents/caregivers should be reminded of during the second or third consultation includes:

|

0% (0) | 2.3% (1) | 97.7% (43) | 9 | Strong consensus |

| 27 | At subsequent visits, the following information may be covered with parents/caregivers:

|

4.5% (2) | 4.5% (2) | 90.9% (40) | 9 | Strong consensus |

| 28 | Intellectual disability is a well-established comorbidity that should be proactively discussed with parents/caregivers early in the course of the disorder. Parents/caregivers should be advised that their child's development will be observed to identify potential developmental concerns and so allow for early intervention | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 100.0% (44) | 9 | Strong consensus |

| 29 | Information to parents/caregivers that should be considered during the second or third consultation regarding patient monitoring includes:

|

2.3% (1) | 2.3% (1) | 95.5% (42) | 9 | Strong consensus |

| 30 | Other information to parents/caregivers that should be considered for the second or third consultation is:

|

2.3% (1) | 9.1% (4) | 88.6% (39) | 9 | Strong consensus |

- Note: %1-2-3 represents the percentage of votes ≤3; n represents absolute number. %4-5-6 represents the percentage of votes ≥4 and ≤6; n represents absolute number. %7-8-9 represents the percentage of votes ≥7; n represents absolute number.

3.2.5 Communication around genetic testing (4 statements)

All statements on genetic testing reached a strong consensus. Voters agreed that the rationale for genetic testing must be discussed with parents/caregivers before the patient's blood is drawn; that parents/caregivers should be informed that not identifying a pathogenic variant in the SCN1A gene does not exclude a diagnosis of Dravet syndrome; that before presenting the genetic testing results to parents/caregivers, they should be reminded that: (i) “genetic” does not mean “hereditary,” emphasizing that if the genetic change is inherited from either parent, this is not the parent's “fault”’; and (ii) genetic testing results do not predict the long-term outcome of the disorder as there is high individual variability. The voters also strongly agreed that genetic testing results should be presented to parents/caregivers by the specialist in an outpatient setting, according to local guidance, and preferably face-to-face, and that there should be sufficient time to answer parents'/caregivers' questions (e.g., future pregnancies, siblings, etc.). Results should be provided in conjunction with genetic counseling, if available (Table 3).

| Statements | %1-2-3 (n) | %4-5-6 (n) | %7-8-9 (n) | Median | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 | The rationale for genetic testing must be discussed with parents/caregivers before blood is drawn. | 2.3% (1) | 6.8% (3) | 90.9% (40) | 9 | Strong consensus |

| 32 | Parents/caregivers should be informed that not identifying a mutation does not exclude a diagnosis of Dravet syndrome since it is a clinical diagnosis. | 2.3% (1) | 0% (0) | 97.7% (43) | 9 | Strong consensus |

| 33 | Before presenting genetic testing results:

|

2.3% (1) | 0% (0) | 97.7% (43) | 9 | Strong consensus |

| 34 | Genetic testing results should be presented to parents/caregivers by the specialist in an outpatient setting, according to local guidance, preferably face-to-face. Sufficient time should be dedicated to answer parents'/caregivers' questions (e.g., future pregnancies, siblings, etc.), and results should be provided in conjunction with genetic counseling, if available. | 2.3% (1) | 4.5% (2) | 93.2% (41) | 9 | Strong consensus |

- Note: %1-2-3 represents the percentage of votes ≤3; n represents absolute number. %4-5-6 represents the percentage of votes ≥4 and ≤6; n represents absolute number. %7-8-9 represents the percentage of votes ≥7; n represents absolute number.

4 DISCUSSION

This study provides key recommendations for the communication of a Dravet syndrome diagnosis to parents/caregivers. These recommendations from international Dravet syndrome experts address crucial components of the HCP-caregiver discussion at a first diagnosis consultation, including explanation of key characteristics of the disease and its evolution, seizure types/triggers/variability, and the high incidence of prolonged seizures and status epilepticus, with emphasis on the importance of carrying an up-to-date acute seizure management protocol (statement #13, Table 1). This is in line with recent recommendations that all children with a diagnosis of Dravet syndrome should have a personalized emergency protocol which should be completed, signed and stamped by the neurologist, and always accompany the patient for emergency staff in the event of a long-lasting severe seizure.24

Recommendations for the first diagnosis consultation also include information about treatments for Dravet syndrome (Tables 1 and 2). Consensus was reached in communicating about the need for long-term treatment(s) for the prevention and reduction of seizure frequency and duration, and preferred medications to treat Dravet syndrome. Current therapeutic guidelines recommend valproic acid as first-line therapy for Dravet syndrome, with clobazam, stiripentol, or fenfluramine as first- or second-line therapy, and pharmaceutical grade cannabidiol as a third-line option, while carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, or phenytoin (except to treat statues epilepticus in certain cases) are contraindicated in these patients.20 When drug-related adverse events or interactions are suspected, monitoring ASM blood levels can be relevant.20, 23

One statement (statement #30, Table 2) stresses the importance of recommending vaccination to caregivers. The fact that some children with Dravet syndrome experience seizure onset after vaccination can lead to vaccine hesitancy in this population. However, it has been demonstrated that vaccines do not alter the disease course or outcome, and are highly recommended.40

Expert voters agreed that Dravet syndrome is a clinical diagnosis and can be discussed with caregivers before the genetic results are available (statements #8 and #32, Tables 1 and 3). This is in line with the position statement by the International League Against Epilepsy, affirming that the absence of a gene variant should not preclude a clinical diagnosis of Dravet syndrome, and its treatment should not be delayed in the setting of a clinical diagnosis.41 Relevance is also given to reduce parental guilt when the genetic variant found in the patient with Dravet syndrome turns out to be inherited (statement #33, Table 3).

Despite clinical recommendations and caregiver desires, many pediatric and adult neurologists do not routinely inform individuals with epilepsy and their families about SUDEP.42, 43 Recent consensuses already recommend informing families of patients with Dravet syndrome of the risk of SUDEP.20, 25 Importantly, this study adds a notion of temporality, strongly advising HCPs to discuss SUDEP with caregivers as soon as the diagnosis is made or very soon afterwards (statement #17, Table 1).

This study focused on giving a diagnosis to parents/caregivers of young children. As such, the description of comorbidities was not covered in detail in the statements, when patients are not yet or mildly affected by DS-related motor and intellectual comorbidities. Information about late stages of the disease and associated comorbidities was purposely not addressed in detail as to not overwhelm the caregivers. Nevertheless, it is important to give information regarding early monitoring and management of these comorbidities, as described in statements #27 to #30.

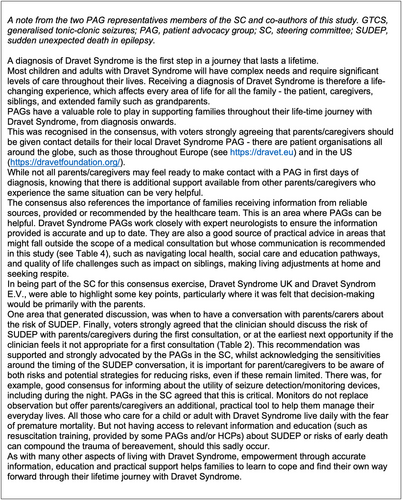

It is worth noting that these recommendations, which include the voice and perspectives of caregivers (Figure 2 and Figure 3) and complement already existing consensus guidelines for diagnosis and disease management,18, 20, 24 leave room for final decision by the clinician, employing terms such as “should” or “if possible” and avoiding direct wording, as communication needs to be highly individualized and consider family situations and educational levels.

This study presents various limitations. Although the Delphi consensus is a structured method, it has inherent limitations tied to the composition of the voting panel, the survey instrument, and the criteria utilized for consensus definition.44 To mitigate these biases, (i) a rigorous method was used to establish a two-part consensus: a consensus rate (75% of responses ≥7) to measure overall agreement and a median score (≥8) to assess response distribution; (ii) selection of voters was based on their expertise and knowledge, confirmed by the voting group characteristics, with a median of 20 years of experience in managing Dravet syndrome patients, and 93% of the panel involved in Dravet syndrome research within the past 5 years (Figure 2). Furthermore, the low attrition rate (4.5%) across the two voting rounds indicates a high level of engagement from the voting panel; (iii) the study ensured strict separation between the expert panelists and the SC members, who neither voted nor directly interacted with the participants, who were interviewed anonymously. The design of our Delphi procedure does not allow subgroup analysis, although it would have been interesting to look at the specific results of patient associations.

One limitation concerns statement #22 about PAG referral. Associations with a focus on supporting Dravet syndrome families may not be available in all countries. However, caregivers may choose to refer to supranational associations or associations with focus in rare epilepsies or diseases in order to retrieve quality information.

Although the number of voters in this study fell below the initial target of 60 participants, it was comparable to other Delphi studies in epilepsy or Dravet syndrome.20, 25, 37-39 All target countries were represented, although the number of participants per country was imbalanced, which may illustrate a greater influence on the present recommendations of clinical practice in some countries versus others. In addition, a larger representation of healthcare profiles other than child neurologists (e.g., neuropsychiatrists, neuropsychologists, nurses, genetic counselors) would have been desirable. Also, certain participants with different healthcare profiles practiced in the same care center, thus increasing group influence in the results.

The scope of this study was intentionally restricted to the communication around diagnosis in young children, in line with the expectation that diagnoses nowadays are made mainly in young children thanks to recent genetic and medical advances.19

5 CONCLUSION

Receiving the diagnosis of Dravet syndrome is particularly challenging for parents/caregivers. The high emotional impact and the sheer volume of information to be received in a limited timeframe mean that giving the diagnosis must be carefully considered and structured by HCPs. This international Delphi consensus offers HCPs managing patients with Dravet syndrome a structured set of pragmatic guidance for orderly and assertive communication with parents/caregivers specifically during the communication of the diagnosis, including recommended initial information to give to parents/caregivers about the disease and its management. It is hoped that these key recommendations will be used to better structure initial diagnosis consultations (and beyond) to support parent/caregivers at this challenging time.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were part of the Steering Committee (SC) except Dr. Cardenal-Muñoz, an employee of Biocodex, to minimize interference. ECM contributed to study conceptualization, literature review, and manuscript preparation. All members of the SC equally contributed to this study: defined the final scope of the study, reviewed literature, formulated (or reformulated) statements for first and second rounds of voting. RSC supervised study and SC. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content and integrated revisions and agreed to the publication of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study received institutional support and was funded from Biocodex.

The Steering Committee would like to thank the participants in the rating group (Table S1). The study received operational and editorial support from an independent medical publishing and communications agency (Medical Education Corpus). English revision and proofreading of the article was done by an independent medical writing agency (A–Z Medical Writing). We thank Medical Education Corpus and A–Z Medical Writing for their support in the development of this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Prof. AB has received honoraria for presenting at educational events, advisory boards and consultancy work for Biocodex, Encoded Therapeutics, Jazz/GW Pharma, Nutricia, Servier, Stoke Therapeutics, and UCB/Zogenix. Mrs. DB received honoraria for consulting and lecture from Eisai and Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Prof. FD received honoraria for consulting from Biocodex, UCB Pharma/Zogenix, Ethos srl, Neuraxpharm Italy S.p.A. Mrs. CE declares no conflict of interest. Mrs. SF declares no conflict of interest. Mr. AG declares no conflict of interest. Dr. KN received honoraria for consulting for Biocodex, UCB Pharma/Zogenix, Eyzs, Takeda, and Longboard. Prof. SSB received honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Biocodex, UCB Pharma, Desitin Arzneimittel, Eisai, Zogenix, GW/Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Ethypharm, Takeda, Marinus Pharma. Dr. ECM is a full-time employee of Biocodex. Dr. RSC received honoraria for presentations and manuscript writing from Biocodex, UCB Pharma/Zogenix. The authors confirm that they have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.