Heart failure, dementia is associated with increased stroke severity, in-hospital mortality and complications

This work was performed at Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China.

Abstract

Background

Heart failure (HF) is a risk factor for ischemic stroke. Cognitive impairment is very common in HF and stroke patients. Patients with HF have higher risk of developing dementia. However, there are limited studies investigating the characteristics, in-hospital mortality and complications of stroke patients with both HF and dementia.

Methods and results

Patients in this study were from the China Stroke Center Alliance database. We divided patients into four groups: (A) stroke patients with dementia but no HF; (B) stroke patients with HF but no dementia; (C) stroke patients with both dementia and HF; (D) stroke patients without HF or dementia. We analysed the in-hospital mortality, and complications among the 4 groups. Outcomes include in-hospital mortality and in-hospital complications, including pneumonia, decubitus ulcer, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, gastrointestinal bleeding and deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Multivariable logistic regression was performed to validate the association between HF, dementia, stroke and functional outcomes. Stroke patients with dementia and HF were older, and had a higher proportion of individuals with a history of strokeperipheral vascular disease and dyslipidaemia, and had a higher level of homocysteine, glycosylated hemoglobin and so on. Compared with group D (stroke patients without HF or dementia), all the other three groups have significantly higher proportion of in-hospital mortality and complications, such as pneumonia, decubitus ulcer, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, DVT, gastrointestinal bleeding and poor swallow function. When compared with group B (stroke patients with HF but no dementia), the in-hospital mortality was higher in group C (stroke patients with HF and dementia), but the difference was not statistically significant; the prevalence of decubitus ulcer, gastrointestinal bleeding and poor wallow function were significantly higher in group C. In the logistic regression, the stroke patients with dementia and HF showed significant higher in-hospital mortality (adjusted OR, 2.875; 95% CI, 1.539–5.371; P = 0.001) and higher proportion of pneumonia (adjusted OR 2.596, 95% CI, 2.027–3.325, P < 0.001), decubitus ulcer (adjusted OR, 6.473, 95% CI, 3.999–10.477, P < 0.001) and pulmonary embolism (adjusted OR, 2.876, 95% CI, 1.054–7.850, P = 0.039).

Conclusions

Stroke patients with dementia and HF have an increased risk of in-hospital mortality and complications. Future studies should strengthen the risk factor control among individuals with both dementia and HF for stroke prevention.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) affecting >23 million people per year worldwide, is a leading cause of death.1 Ischemic stroke also leads to disability and increases mortality.2 HF is a risk factor for ischemic stroke,3 and some studies have found that HF can increase the risk of stroke and accounts for 9% of ischemic stroke cases.4 HF may cause isch-emic stroke by thromboembolism and increased procoagulant factor activity. Previous population-based prospective cohort study demonstrated that HF patients had more than 5-fold increased age- and sex-adjusted risk of ischemic stroke in the first month as compared with participants without HF,5 which was also supported by another community-based study.6 One recent cohort study has demonstrated that the HF patients had 1.5- to 2.1-fold higher risk of ischemic stroke compared with the general population from 31 days to 30 years of follow-ups.7 The poor cerebral hypoperfusion or cerebral inflammation, stemming from reduced cardiac output and HF, may contribute to amyloid deposits or vascular cognitive impairment.8 HF has been shown to affect the risk of developing vascular dementia9 and Alzheimer's disease (AD).10 About 44% of HF patients in Asian have cognitive impairment.11 Nearly 50% patients have multiple-domains impairment.

Dementia is very common in elders and is regarded as an independent predictor of poor functional outcomes after stroke.12 Stroke and dementia interacted with each other.13 The prevalence of post stroke dementia ranged from 7.4% in first-ever stroke to 41.3% in hospital-based studies of recurrent stroke. About 10% of patients have dementia before the first stroke.14 Pre-existing cognitive impairment was reported to be a risk factor for poor functional outcomes15-17 and death17 after stroke. Considering the scarcity of epidemiological data about the effects of HF and dementia on in-hospital outcomes in stroke patients and the increased poor prognosis observed with HF or dementia in stroke patients, we suspected that stroke patients with HF and dementia might be associated with the increased risk of poor outcomes. Therefore, this study aims to compare the in-hospital mortality and complications among the 4 groups (A: stroke patients with dementia but no HF; B: stroke patients with HF but no dementia; C: stroke patients with both dementia and HF; D: stroke patients without HF or dementia).

The Chinese Stroke Center Alliance (CSCA) was developed by the Chinese Stroke Association with the goal of improving healthcare quality for patients admitted with acute stroke.18 In this analysis, we aim to determine the effects of HF and dementia in stroke patients on early functional outcomes and in-hospital mortality in these patients using data from CSCA. The results will elucidate the relationship between HF, dementia, the risk of in-hospital mortality, and early poor functional outcomes in stroke patients, providing clinical evidence for strengthening risk factors management.

Methods

Study design and population

The data in this study were retrieved from the CSCA. It is a national and hospital-based registry cohort study enrolled patients with acute stroke from 1476 hospitals in China.18 The design of the CSCA study have been described previously.18

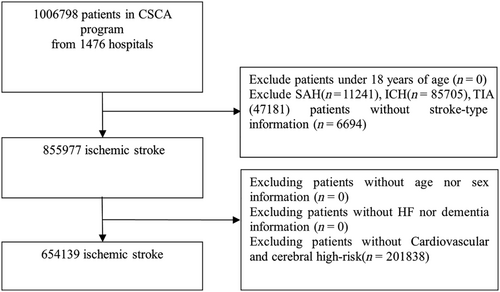

For the patient population of the CSCA, the inclusion criteria included1: aged 18 years or older2; diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke confirmed by brain computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)3; Admission within 7 days of symptom after onset of acute ischemic stroke. Patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage, intracranial haemorrhage, transient ischemic attack (TIA), cerebral venous sinus thrombosis or non-cerebrovascular diseases were excluded. Ischemic stroke patients without any of the cardiovascular risk factors were also excluded. In this study, as the subjects were patients with ischemic stroke with or without a history of dementia or HF (Figure 1). We divided patients into four groups: (A): stroke patients with dementia but no HF; (B): stroke patients with HF but no dementia; (C): stroke patients with both dementia and HF; (D): stroke patients without dementia or HF.

Dementia and HF diagnosis were based on a self-reported history of dementia confirmed by the medical records provided by family members.

Among the participants, 855 977 patients were diagnosed with ischemic stroke. A total of 201 838 patients with missing data, including risk-factor information were excluded. Therefore, a total of 654 139 patients were enrolled in the final study, 3760 (0.58%) stroke patients with dementia but no HF, 8661 (1.32%) stroke patients with HF but no dementia, 317 (0.05%) stroke patients with both dementia and HF, and 641 401 (98.05%) stroke patients without dementia or HF.

This study was approved by the ethics committee at each study centre in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the subjects gave informed consent.

Assessment of epidemiological and clinical information

Demographics (age, sex and education level), medical history and laboratory tests were collected at admission. History of disease (such as hypertension and diabetes), medications usage before admission (antiplatelet, anticoagulation, antihypertensive, lipid-lowing and anti-diabetic drugs), clinical index including systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure and body mass index (BMI), laboratory tests [such as low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C), homocysteine (HCY), glycosylated haemoglobin (GHb), fasting glucose, serum creatinine (Cr), blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and uric acid (UA)] and clinical assessment [National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score and modified Rankin Scale score (mRS)] were also recorded in the study.

We also calculated the CHA2DS2-VASc score [congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 (doubled), diabetes, previous stroke/TIA/thromboembolism (doubled), vascular disease, age: 65–74, sex (female)]. The in-hospital mortality and complications were recorded.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was in-hospital mortality. The secondary outcome was in-hospital complications, including pneumonia, decubitus ulcer, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, gastrointestinal bleeding, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and poor swallow function.

Statistical analysis

In this study, patients were divided into four groups. Continuous variables, if they were normally distributed, were presented as means ± standard deviations or median (quartile) according to their distribution (normal or skewed). Pearson's χ2 test or Fisher's exact test was used to determine the group differences for categorical variables. Statistical comparisons of continuous variables were performed using ANOVA or the Kruskal–Wallis U test (comparison of more than two groups).

Multiple logistic regression models were used to assess the association between dementia or HF and in-hospital mortality and complications in stroke patients. In this study, we defined two models. In model 1, we adjusted for age, sex and education level. In model 2, we adjusted for age, sex, education level, BMI, current smoking, drinking, prior stroke or TIA or ICH, prior myocardial infarction, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, peripheral vascular disease, atrial fibrillation, diabetes and CHA2DS2-VASc score. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Among 1 006 798 patients in the CSCA programme from 1476 hospitals, 11 241 patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage, 85 705 patients with intracranial haemorrhage, 47 181 patients with TIA, 6694 patients without stroke-type information were excluded. And 201 838 patients who have no risk factors were excluded. The final study population was 654 139 patients from 1476 hospitals, representing the final cohort included in our analysis (Figure 1).

Baseline demographics

Table 1 showed the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients. Of 654 139 patients with ischemic stroke hospitalized, there were 3760 (0.58%) stroke patients with dementia but no HF (group A), 8661 (1.32%) stroke patients with HF but no dementia (group B), 317 (0.05%) stroke patients with dementia and HF (group C) and 641 401 (98.05%) stroke patients without dementia or HF (group D) (Table 1).

| Variables | Total (n = 654 139) | Group A (n = 3760) | Group B (n = 8661) | Group C (n = 317) | Group D (n = 641 401) | P value | P value A vs. B | P value A vs. C | P value A vs. D | P value B vs. C | P value B vs. D | P value C vs. D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year, mean ± SD) | 66.7 ± 11.6 | 75.3 ± 10.4 | 74.0 ± 11.0 | 76.1 ± 11.1 | 66.6 ± 11.5 | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.18 | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Sex (male, %) | 400 943 (61.3) | 2032 (54.0) | 4292 (49.6) | 162 (51.1) | 394 457 (61.5) | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.31 | <0.001** | 0.59 | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Education level | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.01** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | |||||

| Below elementary | 19 654 (3.0) | 148 (3.9) | 201 (2.3) | 9 (2.8) | 19 296 (3.0) | |||||||

| High school | 195 286 (29.9) | 981 (26.1) | 2061 (23.8) | 116 (36.6) | 192 128 (30.0) | |||||||

| College | 197 389 (30.2) | 1400 (37.2) | 3525 (40.7) | 141 (44.5) | 192 323 (30.0) | |||||||

| Unknown | 241 810 (37.0) | 1231 (32.7) | 2874 (33.2) | 51 (16.1) | 237 654 (37.1) | |||||||

| Physical examination, mean (SD) | ||||||||||||

| SBP, mmHg | 151.7 ± 23.0 | 148.1 ± 24.2 | 146.3 ± 24.7 | 146.2 ± 22.6 | 151.8 ± 23.0 | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.19 | <0.001** | >0.99 | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| DBP, mmHg | 87.6 ± 14.0 | 84.4 ± 14.1 | 84.6 ± 15.2 | 84.6 ± 13.4 | 87.6 ± 14.0 | <0.001** | 0.57 | 0.77 | <0.001** | >0.99 | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| BMI | 24.1 ± 4.3 | 23.3 ± 4.5 | 23.6 ± 5.1 | 23.3 ± 3.7 | 24.1 ± 4.3 | <0.001** | 0.002** | 0.85 | <0.001** | 0.23 | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 3.2 ± 1.5 | 4.2 ± 1.6 | 4.9 ± 1.7 | 5.8 ± 1.7 | 3.2 ± 1.5 | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| mRS score before onset | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.11 | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | |||||

| 1 | 495 870 (75.8) | 1686 (44.8) | 5649 (65.2) | 157 (49.5) | 488 378 (76.1) | |||||||

| 2 | 158 135 (24.2) | 2074 (55.2) | 3012 (34.8) | 160 (50.5) | 152 889 (23.8) | |||||||

| NIHSS score at admission | ||||||||||||

| N, miss (%) | 130 986 (20.0) | 785 (20.9) | 1437 (16.6) | 45 (14.2) | 128 719 (20.1) | |||||||

| (score, mean ± SD) | 5.0 ± 5.4 | 8.0 ± 7.1 | 8.7 ± 7.8 | 9.5 ± 8.6 | 4.9 ± 5.3 | <0.001** | 0.007** | 0.03* | <0.001** | 0.09 | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Medical history, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Prior stroke or TIA | 276 195 (42.2) | 2306 (61.3) | 4068 (47.0) | 260 (82.0) | 269 561 (42.0) | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Prior ICH | 19 838 (3.0) | 167 (4.4) | 227 (2.6) | 49 (15.5) | 19 395 (3.0) | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.03* | <0.001** |

| Hypertension | 539 638 (82.5) | 2554 (67.9) | 5998 (69.3) | 257 (81.1) | 530 829 (82.8) | <0.001** | 0.14 | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.43 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 179 794 (27.5) | 1103 (29.3) | 2166 (25.0) | 93 (29.3) | 176 432 (27.5) | <0.001** | <0.001** | >0.99 | <0.001** | 0.08 | <0.001** | 0.47 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 64 600 (9.9) | 593 (15.8) | 1454 (16.8) | 82 (25.9) | 62 471 (9.7) | <0.001** | 0.16 | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Myocardial infarction | 14 378 (2.2) | 76 (2.0) | 915 (10.6) | 31 (9.8) | 13 356 (2.1) | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.79 | 0.65 | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Atrial fibrillation | 44 802 (6.8) | 295 (7.8) | 3711 (42.8) | 89 (28.1) | 40 707 (6.3) | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Heart failure | 8978 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 8661 (100) | 317 (100) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | - | - | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 14 648 (2.2) | 238 (6.3) | 493 (5.7) | 34 (10.7) | 13 883 (2.2) | <0.001** | 0.17 | 0.003** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Current smoking | 146 427 (22.4) | 364 (9.7) | 1057 (12.2) | 29 (9.1) | 144 977 (22.6) | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Drinking | 151 235 (23.1) | 567 (15.1) | 1496 (17.3) | 39 (12.3) | 149 133 (23.3) | <0.001** | 0.003** | 0.18 | <0.001** | 0.02* | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Medication history, n(%) | ||||||||||||

| Antiplatelet | 167 537 (25.6) | 1531 (40.7) | 3662 (42.3) | 193 (60.9) | 162 151 (25.3) | <0.001** | 0.10 | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Anticoagulation | 31 822 (4.9) | 206 (5.5) | 1076 (12.4) | 84 (26.5) | 30 456 (4.7) | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.04* | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Antihypertensive | 388 783 (59.4) | 1991 (53.0) | 4980 (57.5) | 223 (70.3) | 381 589 (59.5) | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Diabetic medication | 139 980 (21.4) | 908 (24.1) | 1788 (20.6) | 75 (23.7) | 137 209 (21.4) | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.84 | <0.001** | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.33 |

| Lipid-lowing therapy | 81 351 (12.4) | 835 (22.2) | 1922 (22.2) | 91 (28.7) | 78 503 (12.2) | <0.001** | 0.98 | 0.008** | <0.001** | 0.006** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Laboratory test (mean ± SD) | ||||||||||||

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.8 ± 1.3 | 2.6 ± 1.3 | 2.6 ± 1.3 | 4.0 ± 3.4 | 2.8 ± 1.2 | <0.001** | 0.59 | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.1 |

| HCY, μmol/L | 17.4 ± 13.7 | 19.9 ± 15.8 | 18.3 ± 13.8 | 28.6 ± 24.5 | 17.3 ± 13.6 | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| GHb, % | 6.4 ± 1.9 | 6.4 ± 1.9 | 6.3 ± 1.7 | 8.1 ± 3.7 | 6.4 ± 1.9 | <0.001** | 0.79 | <0.001** | 0.03* | <0.001** | 0.006** | <0.001** |

| FBG, mmol/L | 6.7 ± 3.1 | 6.7 ± 3.1 | 6.7 ± 3.1 | 10.8 ± 8.8 | 6.7 ± 3.1 | <0.001** | 0.79 | <0.001** | 0.91 | <0.001** | 0.52 | <0.001** |

| Cr, mmol/L | 118.2 ± 1019.5 | 130.2 ± 1050.1 | 187.2 ± 1753.4 | 213.5 ± 367.4 | 117.1 ± 1005.9 | <0.001** | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.43 | 0.79 | <0.001** | 0.09 |

| BUN, mmol/L | 5.8 ± 2.5 | 6.3 ± 3.1 | 7.1 ± 3.4 | 8.0 ± 4.0 | 5.8 ± 2.4 | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| UA, μmol/L | 314.2 ± 121.5 | 308.6 ± 124.9 | 357.6 ± 151.6 | 527.9 ± 451.4 | 313.5 ± 120.5 | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.01* | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

- Note: (A) stroke patients with dementia but no heart failure; (B) stroke patients with heart failure but no dementia; (C) stroke patients with both dementia and heart failure; (D) stroke patients without heart failure or dementia.

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CHA2DS2-VASc, Congestive Heart failure, hypertension, Age ≥ 75 years, Diabetes mellitus, Stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), Vascular disease, Age 65 to 74 years, Sex category, Cr, serum creatinine; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FBG, fasting glucose; GHb, glycosylated haemoglobin; HCY, homocysteine; ICH, intracranial cerebral haemorrhage; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein; mRS, modified Rankin Scale score; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; SBP, systolic blood pressure; UA, uric acid.

- ** p < 0.01.

- * p < 0.05.

Compared with patients in group D, those in the other three groups were older, more female, had higher CHA2DS2-VASc score and mRS score, lower BMI higher level of HCY, BUN and a higher proportion of patients with a history of stroke or TIA, dyslipidaemia, atrial fibrillation and peripheral vascular disease; those in the other three groups were more likely to be on antiplatelet, anticoagulation medication and lipid-lowering drugs, suggesting that they suffered from more vascular injury.

Compared with patients in group B, patients in group C have older age, higher CHA2DS2-VASc score, mRS score and a significantly higher proportion of patients with a history of stroke or TIA, intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH), hypertension, dyslipidaemia and peripheral vascular disease, antiplatelet, anticoagulation, antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drugs, higher levels of LDL, HCY, GHb, FBG, BUN and UA.

In-hospital mortality and complications

Compared with other three groups, stroke patients with dementia and HF had a higher proportion of decubitus ulcer (6.3%). Compared with patients in group B (stroke patients with HF but no dementia), patients with HF and dementia had a significantly higher proporation of gastrointestinal bleed (6.9%) and poor swallow function (28.1%). Patients with HF and dementia had higher in-hospital mortality (3.5%), higher proportion of pneumonia (35.0%), pulmonary embolism (1.3%) and DVT (3.8%), but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 2).

| Variables | Total (n = 654 139) | Group A (n = 3760) | Group B (n = 8661) | Group C (n = 317) | Group D (n = 641 401) | P value | P value A vs. B | P value A vs. C | P value A vs. D | P value B vs. C | P value B vs. D | P value C vs. D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality | 3269 (0.5) | 54 (1.4) | 236 (2.7) | 11 (3.5) | 2968 (0.5) | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.02* | <0.001** | 0.73 | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Pneumonia | 62 485 (9.6) | 999 (26.6) | 2709 (31.3) | 111 (35.0) | 58 666 (9.1) | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.001** | <0.001** | 0.16 | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Decubitus ulcer | 2395 (0.4) | 130 (3.5) | 123 (1.4) | 20 (6.3) | 2122 (0.3) | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.01* | <0.001** | <.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Pulmonary Embolism | 1428 (0.2) | 16 (0.4) | 48 (0.6) | 4 (1.3) | 1360 (0.2) | <0.001** | 0.36 | 0.04* | 0.005** | 0.10 | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Myocardial infarction | 3099 (0.5) | 26 (0.7) | 279 (3.2) | 9 (2.8) | 2785 (0.4) | <0.001** | <0.001** | <.001** | 0.02* | 0.70 | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 9596 (1.5) | 214 (5.7) | 201 (2.3) | 22 (6.9) | 9159 (1.4) | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.36 | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| DVT | 6422 (1.0) | 77 (2.0) | 188 (2.2) | 12 (3.8) | 6145 (1.0) | <0.001** | 0.66 | 0.04* | <0.001** | 0.06 | <0.001** | <0.001** |

| Poor swallow function | 60 848 (9.3) | 967 (25.7) | 1977 (22.8) | 89 (28.1) | 57 815 (9.0) | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.36 | <0.001** | 0.03* | <0.001** | <0.001** |

- Note: (A) Stroke patients with dementia but no heart failure; (B) Stroke patients with heart failure but no dementia; (C) Stroke patients with both dementia and heart failure; (D) Stroke patients without heart failure or dementia.

- Abbreviation: DVT, deep vein thrombosis.

- * p < 0.05.

- ** p < 0.01.

The associations between dementia and HF and in-hospital mortality and complications in stroke patients were further explored using logistic regression analysis (Table 3). In unadjusted logistic regression analysis, dementia and HF in stroke patients were associated with increased risks of in-hospital mortality and in-hospital complications, such as pneumonia, decubitus ulcer, pulmonary embolism, gastrointestinal bleeding, DVT and poor swallow function. After adjusting for all the possible confounders, dementia and HF remained to be an independent factor for in-hospital mortality (OR, 2.875; 95% CI, 1.539-5.371, P = 0.001), pneumonia (OR, 2.596 95% CI, 2.027-3.325, P<0.001), decubitus ulcer (OR, 6.473; 95% CI, 3.999-10.477, P<0.001) and pulmonary embolism (OR, 2.876; 95%CI, 1.054-7.850, P = 0.039) in stroke patients.

| Variables | Crude results | Adjusted results (model 1) | Adjusted results (model 2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| In-hospital mortality | ||||||

| Stroke with dementia but no heart failure | 3.136 (2.391–4.112) | <0.001** | 1.959 (1.491–2.573) | <0.001** | 1.990 (1.504–2.632) | <0.001** |

| Stroke with heart failure but no dementia | 6.035 (5.276–6.902) | <0.001** | 4.154 (3.624–4.762) | <0.001** | 2.395 (2.031–2.824) | <0.001** |

| Stroke with heart failure and dementia | 7.745 (4.239–14.149) | <0.001** | 4.727 (2.576–8.673) | <0.001** | 2.875 (1.539–5.371) | 0.001** |

| Stroke without heart failure or dementia | ||||||

| In-hospital complications | ||||||

| Pneumonia | ||||||

| Stroke with dementia but no heart failure | 3.597 (3.345–3.869) | <0.001** | 2.441 (2.265–2.630) | <0.001** | 2.390 (2.214–2.580) | <0.001** |

| Stroke with heart failure but no dementia | 4.521 (4.317–4.735) | <0.001** | 3.314 (3.160–3.477) | <0.001** | 2.310 (2.189–2.438) | <0.001** |

| Stroke with heart failure and dementia | 5.364 (4.259–6.757) | <0.001** | 3.530 (2.781–4.482) | <0.001** | 2.596 (2.027–3.325) | <0.001** |

| Stroke without heart failure or dementia | ||||||

| Decubitus ulcer | ||||||

| Stroke with dementia but no heart failure | 10.797 (9.019–12.927) | <0.001** | 6.770 (5.639–8.128) | <0.001** | 5.486 (4.547–6.619) | <0.001** |

| Stroke with heart failure but no dementia | 4.340 (3.615–5.212) | <0.001** | 2.879 (2.393–3.465) | <0.001** | 1.951 (1.575–2.417) | <0.001** |

| Stroke with heart failure and dementia | 20.287 (12.874–31.969) | <0.001** | 11.926 (7.524–18.904) | <0.001** | 6.473 (3.999–10.477) | <0.001** |

| Stroke without heart failure or dementia | ||||||

| Pulmonary embolism | ||||||

| Stroke with dementia but no heart failure | 1.986 (1.212–3.254) | 0.007** | 1.774 (1.081–2.912) | 0.023 | 1.382 (0.813–2.348) | 0.232 |

| Stroke with heart failure but no dementia | 2.824 (2.134–3.738) | <0.001** | 2.585 (1.949–3.428) | <0.001** | 1.463 (1.059–2.021) | 0.021* |

| Stroke with heart failure and dementia | 7.856 (3.242–19.034) | <0.001** | 6.971 (2.873–16.916) | <0.001** | 2.876 (1.054–7.850) | 0.039* |

| Stroke without heart failure or dementia | ||||||

| Myocardial infarction | ||||||

| Stroke with dementia but no heart failure | 1.584 (1.075–2.334) | 0.0199* | 1.261 (0.855–1.860) | 0.2416 | 1.300 (0.867–1.949) | 0.205* |

| Stroke with heart failure but no dementia | 7.851 (6.934–8.889) | <0.001** | 6.693 (5.898–7.596) | <0.001** | 2.113 (1.789–2.496) | <0.001** |

| Stroke with heart failure and dementia | 7.819 (4.162–14.689) | <0.001** | 6.213 (3.301–11.696) | <0.001** | 1.501 (0.712–3.168) | 0.2861 |

| Stroke without heart failure or dementia | ||||||

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | ||||||

| Stroke with dementia but no heart failure | 4.166 (3.624–4.790) | <0.001** | 4.206 (3.654–4.841) | <0.001** | 3.667 (3.178–4.230) | <0.001** |

| Stroke with heart failure but no dementia | 1.640 (1.424–1.889) | <0.001** | 1.621 (1.406–1.869) | <0.001** | 1.337 (1.146–1.559) | 0.0002** |

| Stroke with heart failure and dementia | 5.152 (3.339–7.947) | <0.001** | 4.894 (3.169–7.559) | <0.001** | 3.259 (2.091–5.078) | <0.001** |

| Stroke without heart failure or dementia | ||||||

| DVT | ||||||

| Stroke with dementia but no heart failure | 2.161 (1.722–2.712) | <0.001** | 1.769 (1.409–2.222) | <0.001** | 1.496 (1.187–1.887) | 0.0007** |

| Stroke with heart failure but no dementia | 2.294 (1.981–2.656) | <0.001** | 1.928 (1.663–2.234) | <0.001** | 1.143 (0.970–1.346) | 0.1099 |

| Stroke with heart failure and dementia | 4.067 (2.283 7.245) | <0.001** | 3.250 (1.823–5.797) | <0.001** | 1.720 (0.948–3.121) | 0.0745 |

| Stroke without heart failure or dementia | ||||||

| Poor swallow function | ||||||

| Stroke with dementia but no heart failure | 3.499 (3.250–3.766) | <0.001** | 2.665 (2.473–2.871) | <0.001** | 2.604 (2.412–2.812) | <0.001** |

| Stroke with heart failure but no dementia | 2.988 (2.840–3.144) | <0.001** | 2.342 (2.224–2.467) | <0.001** | 1.648 (1.555–1.746) | <0.001** |

| Stroke with heart failure and dementia | 3.943 (3.086–5.039) | <0.001** | 2.884 (2.249–3.698) | <0.001** | 2.100 (1.622–2.719) | <0.001** |

| Stroke without heart failure or dementia | ||||||

- DVT= deep vein thrombosis. Model 1: Adjusted for age, sex and education level. Model 2: Adjusted for age, sex, education level, BMI, current smoking, drinking, prior stroke or TIA or ICH, prior myocardial infarction, hypertension, dyslipidemia, peripheral vascular disease, atrial fbrillation, diabetes and CHA2DS2-VASc score.

- * p < 0.05.

- ** p < 0.01.

Discussion

In the current study, we found that histories of dementia and HF was associated with a higher rate of in-hospital mortality and complications such as pneumonia, decubitus ulcer and pulmonary embolism in acute ischemic stroke patients. Prior literature reported that patients with both dementia and HF had a higher risk of death.19 In addition, the recent study also indicated that stroke patients with dementia and HF should be given more care and targeted treatment because that their condition may progress differently and more quickly compared with other individuals.

In this study, we found that the stroke patients with HF are associated with high risks of in-hospital death and complications, such as pneumonia, decubitus ulcer and pulmonary embolism. Previous study showed that the incidence of stroke is higher in patients with HF than patients with cancers.20 Stroke is a catastrophic complication of HF.21 study reported that a history of heart disease was associated with stroke mortality.22 The HF may promote endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerosis and hypercoagulability induced by inflammation, which is contributed to stroke. On the other hand, the microvascular dysfunction in both brain and heart may lead to cognitive impairment and heart failure. Compared with HF patients with no stroke, HF patients with stroke was associated with markedly increased risk of death. (all-cause mortality rate: 4.0 (95% CI, 3.7–4.3) per 100 patient-years vs. 27.8 (95% CI, 22.1–35.0) per 100 patient-years).23 These findings support a predictive effect of HF in stroke poor outcome.

Nearly 0.3% ischemic stroke patients have any type of dementia in China.24 Dementia, either degenerative or vascular brain pathology, could predict the mortality25 and poor in-hospital outcomes for stroke patients.24, 26 Prior study suggested that pre-stroke mobility was worse in patients with dementia, and together with dementia was associated with mortality at 1 and 3 months after stroke.13 The reasons for the increased mortality were that dementia maybe associated with more severe vascular deficits, and a higher risk of developing complications. Secondly, dementia itself maybe an already weak individual, it is difficult to respond to stroke injury or aggressions. Thirdly, the patients with dementia often received less effective treatment partially because of poor compliance, such as anticoagulant drugs, thrombolysis and endovascular treatment.27 Also the demented patients are usually not well control the vascular risk factors. One study demonstrated that patients with AD and mixed dementia might have worse survival after stroke when compared with patients with vascular dementia.25 However, some studies reported that the pre-stroke dementia was not an independent predictor for death.28 They considered that the death was probably due to the stroke characteristics rather than the pre-stroke dementia.29 This difference might be due to different baseline characteristics.

HF was associated with an increased risk of dementia because of hypoperfusion. The HF patients had a 21% higher risk of developing dementia.30 HF can also cause inflammation, leading to cerebral endothelial dysfunction and microvascular dysfunction. Another study also reported that the amyloid-β accumulation in both brain and heart may indicate a shared pathogenesis of both dementia and HF,31 they share pathophysiologic mechanisms and can occur concomitantly.32 In this study, we found that stroke patients with HF and dementia have an increased risk of in-hospital mortality. There are several reasons. Patients with dementia might be more likely to suffer from stroke because of reduced neuroplasticity and neuronal loss, which may explain worsening of dementia and poorer recovery after stroke.33 Patients with dementia were with less opportunity to achieve sufficient rehabilitation. Secondly, stroke is not timely found in dementia patients, missing the window for acute reperfusion treatments. These reperfusion treatments may not be active because of reduced life expectancy.34 As we all known, patients receiving acute reperfusion treatment might have a favourable prognosis.35 It needs better understanding the complex relationship among dementia, HF, and mortality in stroke patients.

In this study, patients with HF and dementia were significantly elder than other three groups. Both HF36 and dementia are associated with ageing.37 Age was a key predictor of poor outcome. In this study, we found that stroke patients with HF and dementia have a higher risk of in-hospital mortality even after adjusting age. As for gender difference, previous study showed that the proportion of men (68.9%) was higher than women (31.1%) in acute stroke.38 Other study suggested that women with stroke were more likely to experience AD than men, while had lower risk of having vascular dementia.10 In this study, we found that stroke with dementia and HF have higher percentage of male. That because it did not record particularly the dementia types, the association of between dementia and stroke outcome in females might be underestimated. However, in this study, we found that stroke patients with HF but no dementia have higher percentage of female. A recurrent study found that the prevalence of HF in female was higher than that in male.39 Stroke patients with dementia have highest rate of illiteracy. This result is consistent with previous studies,40 suggesting that higher education levels is a protective factor against dementia in patients with vascular disease. Lower education level is a well-known risk factor for AD, as it may be associated with poorer cognitive performance and reserve.41

As previously mentioned, several studies indicated that co-morbidity in stroke was very common. Co-morbidities have a strong impact on outcome and mortality after stroke. The Swedish Stroke Register (Riksstroke) study demonstrated high co-morbidity burden in first-ever ischemic stroke patients, which more than doubled the proportion of poor outcome.42 Dementia patients had a high risk of medical complications and mortality. The histories of dementia, kidney and HF were the strongest predictors of poor outcome in patients with stroke.43 All these previous findings are consistent with our results.

The stroke patients with HF and dementia had more underlying diseases and co-morbidities indicated by higher CHA2DS2-VASc score. Recent study showed that CHA2DS2-VASc could significantly predicted executive function in older patients.44 Higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores in patients with heart disease were found to be associated with increased risks of stroke, dementia and mortality.45 Patients have histories of HF and dementia took more medications (antiplatelet, anticoagulation, antihypertensive, diabetic medication, lipid-lowering medicine) before admission. It might be related to more co-morbidities and favourable medication adherence. Patients with HF with dementia may be reminded to take their medications by caregivers. However, stroke patients without HF or dementia (group D) have a lower usage of medications (antiplatelet agents, anticoagulation and lipid-lowering medicine), mostly associated with poor adherence to medication. Lifestyle risk factors are reported to be associated with low health literacy.46 Patients with low health literacy might have difficulties in complex health tasks, getting and understanding health information, as well as prevention measures.46 Evidence has showed that the low health literacy was related to increasing mortality in patients with cardiovascular diseases after adjusting for cognition.47 These findings further highlight the significance of early identification and treatment of risk factors for stroke and cognition. The median in-hospital NIHSS score was higher in stroke patients with HF and dementia, which means that the severity of stroke in patients with HF and dementia were significantly severer than other three groups. An increased NIHSS score was an independent predictor for mortality in patients with ischemic stroke.

Another significant finding of this study was that the in-hospital mortality and complications of stroke patients with HF and dementia group was significantly higher than those in other 3 groups, even in the fully adjusted models that included potential confounders, such as age, sex, education level, BMI, current smoking, drinking, prior stroke or TIA or ICH, prior myocardial infarction, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, peripheral vascular disease, atrial fibrillation, diabetes and CHA2DS2-VASc score. This means that HF and dementia might be independent risk factors to increase the risk of in-hospital mortality in patients with ischemic stroke. The infection, such as pneumonia, might aggravate in-hospital mortality.

HF and dementia might also be independent risk factors for in-hospital complications, such as pneumonia, decubitus ulcer and pulmonary embolism in hospital. The pulmonary embolism was related to impaired mobility, whereas most patients with HF and dementia usually have limited mobility and long-term bed rest. Thus, our data suggested that the targeted medical care or rehabilitation therapy should be given to elderly patients with HF and dementia. We show a strong influence of co-morbidity on stroke outcomes, and further research is needed to develop a comprehensive therapy that includes multimorbidity as key focus. Better knowledge of the relationship among dementia, HF, and mortality has the potential to guide the development of specialized strategies and improve post-stroke care.

This study has several limitations. First, the CSCA programme contains more tertiary centres, smaller hospitals do not participate in, which may have selection bias. Second, the CSCA database lack the follow-up information. Assessments of 1-year or long-term outcomes, were unavailable. Thirdly, although the diagnosis of dementia was made by a physician, information on dementia was obtained from medical documentation provided by patients' family members, which may underestimate the incidence of dementia. A possible bias could arise from the misdiagnosis of HF or other conditions in patients who actually died of dementia. And we did not classify the specific subtypes of dementia, such as Alzheimer's disease or vascular dementia, which makes it impossible for us to analyse the heterogeneity of different dementia types, and its relationship among HF, stroke and in-hospital mortality and complications. Future study should use cognitive assessment tools to evaluate the prior cognitive status and make classification. Forthly, the HF could be categorized as HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) according to the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). However, we did not address the specific type of HF, which may have different effects on the in-hospital outcomes after stroke. Fifthly, in this study, stroke patients with HF and dementia were older than others. Ageing was associated with poor functional outcome,48, 49 although we adjusted for age in the statistics, we did not completely exclude the impact of age on the poor outcomes after stroke besides HF, dementia and stroke. In the future study, we might also explore the relationship between HF, dementia and functional outcome after stroke according to the stratification of age. Lastly, the CSCA database did not record cognitive-related drug usage, such as donepezil and memantine, which might have an influence on the stroke outcome.

Conclusions

Stroke patients with HF and dementia had increased risks of in-hospital mortality and complications such as pneumonia, decubitus ulcer and pulmonary embolism in acute ischemic stroke patients compared with other patients. It emphases the need to develop a comprehensive approach that concerns co-morbidity to improve and optimize the stroke treatment strategies.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants for their involvement.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Yongjun Wang is an Editorial Board member of CNS Neuroscience and Therapeutics and a co-author of this article. To minimize bias, they were excluded from all editorial decision-making related to the acceptance of this article for publication.

Funding

None.

Open Research

Data availability statement

No additional unpublished data are available.