Real-world comparative effectiveness of sacubitril/valsartan versus RAS inhibition alone in patients with de novo heart failure

Ankeet S. Bhatt and Muthiah Vaduganathan contributed equally to this work.

Abstract

Aims

Large-scale, real-world data on early initiation of sacubitril/valsartan in patients newly diagnosed (de novo) with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) are limited. We examined the effectiveness of sacubitril/valsartan versus angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi)/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) on all-cause and cause-specific hospitalizations among patients with de novo HFrEF from the Optum® dataset in the United States.

Methods

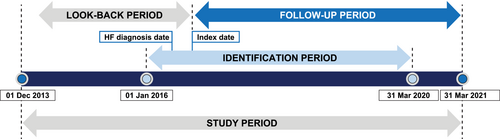

This retrospective cohort study included adult patients with de novo HFrEF (diagnosed ≤30 days) with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤40% who were first prescribed with sacubitril/valsartan or ACEi/ARB from 1 January 2016 to 31 March 2020. The primary endpoint (all-cause hospitalization) and secondary endpoints were analysed in propensity score-matched cohorts.

Results

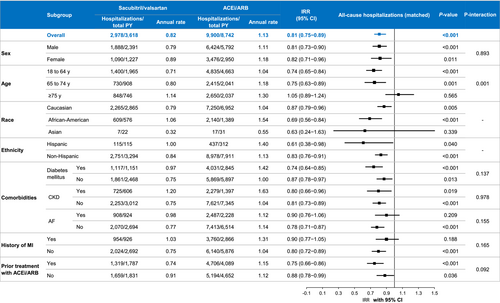

A cohort of 3290 patients with de novo HFrEF who were prescribed with sacubitril/valsartan and a propensity-matched cohort of 6580 patients who were prescribed with ACEi/ARB were analysed. Overall, the mean (SD) age of patients was 63 (14) years, 34% were women, and baseline characteristics were balanced across treatment groups. Hypertension (67%), diabetes (33%) and chronic kidney disease (28%) were highly prevalent comorbidities. Patients in the sacubitril/valsartan cohort when compared with the ACEi/ARB cohort had lower annual rates of all-cause hospitalizations [incidence rate ratio (IRR): 0.81, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.75–0.89, P < 0.001], cardiovascular (CV) hospitalizations (IRR: 0.80, 95% CI: 0.73–0.87, P < 0.001) and HF hospitalizations (IRR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.78–0.95, P = 0.002).

Conclusions

Among patients with de novo HFrEF, sacubitril/valsartan (compared with that of ACEi/ARB) was associated with fewer all-cause, CV and HF hospitalizations. These findings are consistent with clinical trial evidence suggesting potential benefits of early initiation of sacubitril/valsartan in patients with HFrEF, including those soon after diagnosis.

Introduction

International guidelines for the management of heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) strongly recommend switching to sacubitril/valsartan from traditional renin–angiotensin system inhibitors (RASis), namely, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), among symptomatic patients.1, 2 These recommendations are partly based on data from the pivotal Prospective comparison of an ARni with an Acei to Determine the Impact on Global Mortality and morbidity in Heart Failure (PARADIGM-HF) trial that enrolled ambulatory participants with HFrEF. However, PARADIGM-HF specifically excluded patients early after diagnosis with de novo HF.3 Additional evidence from trials including the comParIson Of sacubitril/valsartaN versus Enalapril on Effect on nt-pRo-bnp in patients stabilized from an acute Heart Failure episode (PIONEER-HF) and the Comparison of Pre- and Post-discharge Initiation of LCZ696 Therapy in HFrEF Patients After an Acute Decompensation Event (TRANSITION) trials demonstrated consistent benefits of sacubitril/valsartan compared with traditional RASi (ACEi/ARBs) in patients with acute presentation of HF, including patients newly diagnosed (de novo) or those with worsening HFrEF.4, 5 In the TRANSITION study, patients with de novo HFrEF were more likely to achieve target dosing and had greater absolute reductions in cardiac stress markers.4, 5 However, trials evaluating sacubitril/valsartan in patients with de novo HFrEF were modest in size and included surrogate primary endpoints. In practice, sacubitril/valsartan initiation is often delayed in clinical settings as compared with other conventionally recommended HF therapies, such as ACEi/ARB.6 Therefore, we conducted a retrospective real-world study to examine the comparative effectiveness of sacubitril/valsartan versus ACEi/ARB on clinical outcomes among a contemporary cohort of patients presenting with de novo HF in the United States.

Methods

Data sources and study population

This study used the Optum® deidentified Electronic Health Record dataset (Optum® EHR). The accessed database contains records of ~97 million patients across all main geographical regions in the United States, with proportions of age and race/ethnicity that broadly reflect the overall US population. In addition to the data captured directly from the local EHR structured fields, data [such as left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF)] are extracted from the electronic free-text clinical notes via a natural language processing (NLP) system developed and maintained by Optum.7, 8 Patient-level data were fully deidentified prior to analyses and, therefore, were exempt from institutional review board approval.

Study design

This was a retrospective, propensity-matched, comparative effectiveness study, including individuals ≥18 years of age with de novo presentations of HFrEF and a first prescription for HFrEF of either sacubitril/valsartan or RASi (ACEi/ARB) between 1 January 2016 and 31 March 2020. For this analysis, the index date was indicated as the date of the first prescription of sacubitril/valsartan or new prescription of ACEi/ARB after diagnosis of HF. ACEi and ARB may have been indicated for otherindications prior to incident HFrEF diagnosis. Patients were required to have a first International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revisions, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM) HF diagnosis code9 within 30 days prior to the index date (including the index date). To establish that patients were de novo, the study included only those patients who did not have a previous diagnosis of HF within the 2 year look-back period before the diagnosis associated with the index date. Patients with recorded LVEF > 40% were excluded. Patients with an LVEF of 10% or lower were also excluded, as this may be indicative of patients with end-stage HF for which sacubitril/valsartan is not indicated or may be a potential recording error. Full details of inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in Table S1. Patients were followed from the index date until the end of the study period (31 March 2021) (Figure 1).

Patients were censored at the time of index medication discontinuation, last medical visit or prescription, or death, whichever occurred first. Index medication discontinuation was defined as a newly filled prescription for the alternative medication (e.g., ACEi/ARB filled in those initially filling sacubitril/valsartan at the index date or sacubitril/valsartan filled in those initially filling ACEi/ARB at the index date). Patients on ACEi/ARB for ≤2 days prior to sacubitril/valsartan prescription were allocated to the sacubitril/valsartan cohort, while patients on ACEi/ARB for >2 days before sacubitril/valsartan prescription were assigned to the ACEi/ARB cohort and followed up until prescription of sacubitril/valsartan (Figure S1A,B).

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the rate of all-cause hospitalizations. Hospitalization was defined using admission and discharge dates from the inpatient visits. All inpatient visits within the study duration (excluding the index date) were considered. All-cause hospitalizations were reported in the following time periods: 30 days from the index date, 1 year from the index date and during the entire follow-up period. Key secondary endpoints included time to first all-cause hospitalization and rates of cardiovascular (CV) and HF hospitalizations. CV and HF hospitalizations were defined by ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM (Table S2).10 A key exploratory endpoint was all-cause mortality. The details of endpoint definitions are provided in Table S3. All endpoints were reported for the overall study cohort and examined by key subgroups: demographics including age, race, sex, and the presence of cardiometabolic comorbidities [e.g., prior myocardial infarction, history of diabetes mellitus, history of chronic kidney disease and underlying atrial fibrillation (AF)] and the presence or absence of a history of ACEi/ARB treatment prior to HF diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

Patients meeting the inclusion criteria who were newly initiated on sacubitril/valsartan were matched to patients initiated or continuing treatment on ACEi/ARB. Propensity score matching was performed based on baseline criteria including age, sex, index year, race, ethnicity and geographical region, as well as LVEF, comorbidities [Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (ECI)],11 the presence or insertion of an HF-related device therapy, and other relevant CV medications [including beta-blockers (BBs), calcium channel blockers, loop diuretics and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs)]. LVEF data are provided through the advanced NLP algorithm in Optum® EHR,7, 8 which was specifically designed to extract LVEF values from the physician notes that are singular (e.g., 35%), a range (e.g., 45%–50%) or with a comparator (e.g., >45%). The LVEF data were cleaned according to a previously utilized algorithm (Table S4 for details). The comorbidities evaluated for inclusion in the ECI score were defined by ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes identified during the baseline period.10

The sacubitril/valsartan cohort and ACEi/ARB cohort were matched in a 1:2 fashion using a Greedy Two-To-One algorithm. Baseline characteristics were compared across matched cohorts. Continuous variables were reported as proportions, means [standard deviation (SD)] and median [inter-quartile range (IQR)] as appropriate, while categorical variables were reported as proportions. Negative binomial models were used to compare rates of hospitalizations and adjusted for influential covariates. All-cause hospitalization rates were reported 30 days after index date, 1 year after index date and in the entire follow-up period. Annual hospitalization rates, incidence rate ratio (IRR), 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P values were reported. Cox proportional hazard models were used to compare time to first all-cause hospitalization for patients in the sacubitril/valsartan group versus those in the ACEi/ARB group. All endpoints were analysed using propensity score-matched regression cohorts. All statistical analyses were conducted using R programming language (Version 4.1.0) and RStudio (Version R4.1.0; RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA, USA).

Results

Study population

A total of 58,716 patients were prescribed with sacubitril/valsartan during the identification period, of whom 3290 patients (5.6%) had de novo HF presentations. During the same period, a total of 9,321,620 patients were prescribed with ACEi/ARB, of whom 47,678 patients (0.5%) had de novo HF presentations. These patients formed the unmatched sacubitril/valsartan and ACEi/ARB cohorts, respectively. A complete description of patient eligibility criteria is available in Figure S2. Baseline characteristics of the unmatched cohorts are included in Table S5.

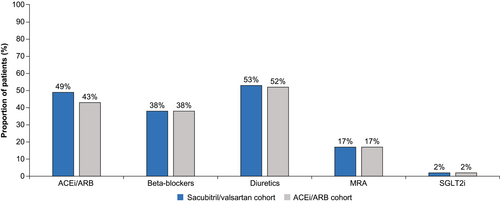

The propensity score-matched cohort included 3290 patients in the sacubitril/valsartan-treated group and 6580 patients in the ACEi/ARB-treated group. Overall, matched patients had a mean (SD) age of 63 (14) years, 34% were female, and 17% were African American across the two cohorts; hypertension (67%), diabetes (33%) and renal impairment (28%) were common. The matched cohorts were similar in their baseline characteristics and comorbidities (Table 1). Guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) for HF was similar among the matched sacubitril/valsartan and ACEi/ARB cohorts (Figure 2).

|

Sacubitril/valsartan n = 3290 |

ACEi/ARB n = 6580 |

P value | SMDa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 63.5 (13.8) | 63.7 (14.4) | 0.201 | 0.021 |

| Age distribution, n (%) | 0.052 | 0.055 | ||

| 18–64 years | 1707 (51.9) | 3377 (51.3) | ||

| 65–74 years | 807 (24.5) | 1516 (23.0) | ||

| ≥75 years | 776 (23.6) | 1687 (25.6) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | 0.863 | 0.004 | ||

| Male | 2166 (65.8) | 4345 (66.0) | ||

| Female | 1124 (34.2) | 2235 (34.0) | ||

| Year of index, n (%) | ||||

| 2016 | 244 (7.4) | 505 (7.7) | 0.923 | 0.020 |

| 2017 | 576 (17.5) | 1156 (17.6) | ||

| 2018 | 878 (26.7) | 1776 (27.0) | ||

| 2019 | 1274 (38.7) | 2541 (38.6) | ||

| 2020 | 318 (9.7) | 602 (9.2) | ||

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Missing/other/unknown | 152 (4.6) | 289 (4.4) | 0.890 | 0.017 |

| African American | 568 (17.3) | 1108 (16.8) | ||

| Asian | 15 (0.5) | 29 (0.4) | ||

| Caucasian | 2555 (77.7) | 5154 (78.3) | ||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Missing/unknown | 224 (6.8) | 440 (6.7) | 0.971 | 0.005 |

| Hispanic | 123 (3.7) | 244 (3.7) | ||

| Not Hispanic | 2943 (89.4) | 5896 (89.6) | ||

| LVEF, mean (SD) | 26.9 (7.4) | 26.8 (7.9) | 0.741 | 0.005 |

| Comorbidities, signs and symptoms, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 2209 (67.1) | 4375 (66.5) | 0.531 | 0.014 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 1742 (53.0) | 3496 (53.1) | 0.881 | 0.004 |

| Shortness of breath | 1566 (47.6) | 3096 (47.1) | 0.623 | 0.011 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1080 (32.8) | 2122 (32.2) | 0.579 | 0.012 |

| Renal impairment | 911 (27.7) | 1823 (27.7) | 1.000 | <0.001 |

| COPD | 525 (16.0) | 1081 (16.4) | 0.569 | 0.013 |

| Sleep apnoea | 530 (16.1) | 1045 (15.9) | 0.793 | 0.006 |

| Depression | 385 (11.7) | 771 (11.7) | 1.000 | <0.001 |

| Anaemia | 190 (5.8) | 374 (5.7) | 0.890 | 0.004 |

| Dementia | 71 (2.2) | 146 (2.2) | 0.903 | 0.004 |

| Cardiac comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 864 (26.3) | 1675 (25.5) | 0.402 | 0.018 |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 1246 (37.9) | 2421 (36.8) | 0.306 | 0.022 |

| CRT-D | 183 (5.6) | 389 (5.9) | 0.513 | 0.015 |

| CRT pacemaker | 50 (1.5) | 110 (1.7) | 0.632 | 0.012 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 332 (10.1) | 699 (10.6) | 0.436 | 0.017 |

| ICD | 10 (0.3) | 22 (0.3) | 0.950 | 0.005 |

| Ischaemic heart disease (including MI) | 1791 (54.4) | 3635 (55.2) | 0.461 | 0.016 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 223 (6.8) | 467 (7.1) | 0.586 | 0.013 |

| Valvular heart disease | 1268 (38.5) | 2474 (37.6) | 0.375 | 0.019 |

- Abbreviations: ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; SD, standard deviation; SMD, standardized mean difference.

- a SMD represents difference in means or proportions between treatment groups, divided by the standard errors. SMD of ≤0.1 indicates that covariates were balanced between the treatment groups after propensity score matching.

Study endpoints

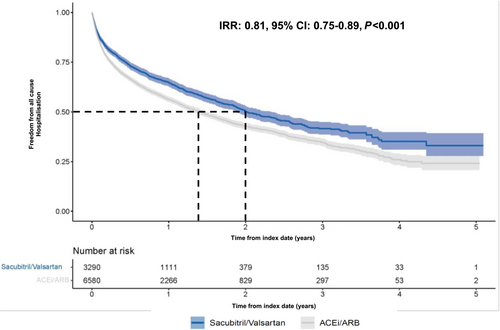

Among the overall matched study populations, there were 12,878 all-cause hospitalizations during follow-up (annual rate: 1.04 hospitalizations/person-year). Patients in the sacubitril/valsartan cohort experienced an annual rate of all-cause hospitalization of 0.82 hospitalizations/person-year compared with 1.13 hospitalizations/person-year among those in the ACEi/ARB cohort (IRR: 0.81, 95% CI: 0.75–0.89, P < 0.001) (Figure 3). The association with fewer all-cause hospitalizations among those in the sacubitril/valsartan cohort, compared with those in the ACEi/ARB cohort, persisted across most of the major subgroups of interest (Figure 4). Patients aged <75 years in the sacubitril valsartan cohort versus the ACEi/ARB cohort had lower rates of all-cause hospitalizations [18–64 years (IRR: 0.74, 95% CI: 0.65–0.84, P < 0.001) and 65–74 years (IRR: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.63–0.89, P = 0.001)], a finding not seen in patients aged ≥75 years (IRR: 1.05, 95% CI: 0.89–1.24, P = 0.565, P for interaction by age = 0.001). The observed association of fewer all-cause hospitalizations in the sacubitril/valsartan cohort was consistent regardless of prior exposure to ACEi/ARB (P for interaction = 0.092). Similar observations were seen in the unmatched patient cohorts (Figure S3).

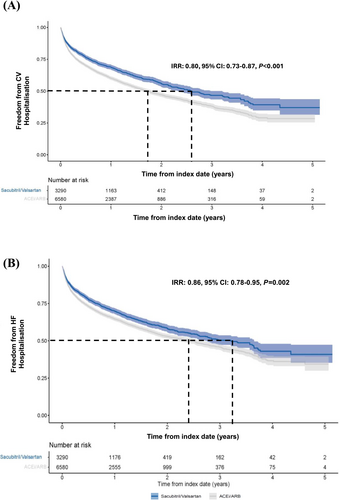

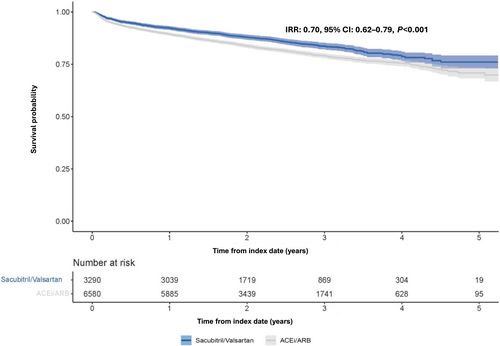

Patients in the matched sacubitril/valsartan versus ACEi/ARB cohorts were associated with a 21% reduction in the expected hazard of all-cause hospitalization at any time after index date [hazard ratio (HR): 0.79, 95% CI: 0.73–0.84, P < 0.001]. Patients in the sacubitril/valsartan cohort had fewer overall CV hospitalizations (IRR: 0.80, 95% CI: 0.73–0.87, P < 0.001) (Figure 5A) and HF hospitalizations (IRR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.78–0.95, P = 0.002) (Figure 5B) compared with those in the matched ACEi/ARB cohort. The results were largely consistent across the major subgroups of interest (Figure S4A–C). There were fewer deaths from any cause in patients in the sacubitril/valsartan cohort compared with those in the ACEi/ARB cohort (IRR: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.62–0.79, P < 0.001) (Figure 6).

Discussion

This retrospective analysis of patients with de novo HFrEF in a large real-world US dataset found that treatment with sacubitril/valsartan was associated with lower annual rates of all-cause and cause-specific hospitalizations compared with ACEi/ARB. The association with fewer hospitalizations in the sacubitril/valsartan cohort appeared consistent across most major subgroups of interest, including those with and without prior exposure to ACEi/ARB. These results further support and inform on the use of sacubitril/valsartan in patients presenting with de novo HFrEF.

The findings from this study are largely consistent with results from a recently conducted retrospective cohort study, which indicated that sacubitril/valsartan was associated with a 13% greater risk reduction in first all-cause hospitalization than ACEi among patients with HFrEF without prior exposure to ACEi/ARB.10 Findings from such real-world studies further support the results of randomized clinical trials with sacubitril/valsartan, including those that specifically included patients with and without prior history of HF and in populations with and without prior exposure to ACEi/ARB.4, 5 Importantly, these trials evaluated surrogate primary endpoints, were modest in size and did not exclusively consider a de novo HFrEF population; therefore, these real-world data are complementary in establishing the potential effectiveness of sacubitril/valsartan versus ACEi/ARB in this high-risk patient population early after diagnosis.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and American Heart Association (AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA) guidelines recommend sacubitril/valsartan for the treatment of chronic HFrEF based on data from the PARADIGM-HF trial. However, PARADIGM-HF excluded patients with acute decompensated HFrEF, patients with de novo HF and patients naïve to ACEi/ARB treatment. Additionally, the trial design included sequential run-in phases, which may have preferentially included those with demonstrated tolerability to ultimately undergo randomization. The guidelines do not provide clear guidance regarding the optimal timing and sequence of initiation of therapy in patients with de novo HFrEF.12 Among patients with de novo HFrEF, large implementation gaps remain, and patients are often not initiated on GDMT even after an acute decompensation event and only after substantial delay.13 Patients hospitalized with de novo presentation of HFrEF are more likely to be younger and female, have non-ischaemic aetiology and fewer comorbidities, and generally have higher post-discharge survival compared with acute on chronic HF.14 However, a substantial morbidity burden remains, due to which one of six patients with de novo HFrEF is likely to experience worsening HF events within 18 months of initial diagnosis and, once progressed to the worsening HF stage, remains at a higher risk of 2 year mortality and recurrent HF hospitalizations.15 Therefore, early medical optimization for this prevalent and high-risk condition is imperative.

In our study, the associations between sacubitril/valsartan (vs. ACEi/ARB) and lower hospitalizations were more apparent in younger and middle-aged patients (<75 years) compared with older patients ≥75 years. Typically, older patients have an excess burden of comorbidities, lower systolic blood pressures, greater frailty and greater competing risks for the outcomes studied. While these factors might influence the continuation of sacubitril/valsartan and have haemodynamic effects, which could place these patients at greater risk for non-HF-related hospitalization, secondary analyses from clinical trials largely support the benefit of sacubitril/valsartan in these populations.16-18 Notably, patients with de novo HFrEF, compared with those with worsening HF, are generally younger with fewer comorbidities, indicating that this population may have an increased tolerability to therapy and may especially benefit from early initiation of sacubitril/valsartan.5, 14, 19

Clinical practice guidelines recommend four-drug therapy for HFrEF, and the most recent update now indicates a Class IB recommendation for the rapid initiation of GDMT shortly following an HF event.2 It has been shown that in clinical practice, a significant proportion of patients with de novo HFrEF remain undertreated, even after an acute decompensation event. These data reinforce the potential role for sacubitril/valsartan initiation shortly after a de novo HF event.13

The early divergence in the Kaplan–Meier curve observed in this study may be attributed to the early initiation of sacubitril/valsartan in newly diagnosed HFrEF patients, leading to significant early reductions in hospitalization rates compared with ACEi/ARB. This early benefit, observed in our study and supported by the PIONEER trial,4 contrasts with the PARADIGM study3 potentially due to differences in patient populations and timing of treatment initiation. Early initiation of sacubitril/valsartan after the initial HF diagnosis can potentially reduce the risk of adverse clinical outcomes and delay disease progression due to reversal of left ventricular remodelling.5, 20, 21 Many barriers towards initiation of sacubitril/valsartan among patients with de novo HFrEF likely exist, including concerns regarding the excess rates of hypotension, the complexity around switching and washout if patients are already receiving ACEi or ARB for other indications (e.g., hypertension), and a lack of transparency around cost and access. Although discontinuation of treatment with sacubitril/valsartan was relatively rare among patients enrolled in clinical trial settings, run-in phases may have preferentially excluded patients at risk for poor tolerability. The data presented here add important insights to the limited pool of evidence that supports prompt initiation of sacubitril/valsartan in newly diagnosed patients with HFrEF to reduce the risk of hospitalizations. These findings add further evidence to support the benefit of early integration of sacubitril/valsartan among a broad, diverse and high-risk real-world population in the United States.

Limitations

The results from this study should be interpreted in the context of a few limitations. Categorization of patients as patients with de novo HF was based on the absence of HF diagnosis codes in the look-back period of 2 years and 29 days from the index date. However, the history of patients beyond the look-back period was not considered, which may have potentially led to mis-categorization of some patients as patients with de novo HF. Patients outside particular integrated delivery networks with captured data were not included in the analysis, which may have contributed to the underestimation of hospitalization rates. Rates of treatment-associated adverse events, such as symptomatic hypotension or electrolyte disturbances, were largely unavailable with substantial missing data and therefore were not evaluated in the context of this analysis. Finally, in the context of a retrospective, nonrandomized, real-world study, the possibility of residual confounding may have impacted the findings despite our attempts at propensity score matching.

Conclusions

Results from this retrospective, comparative effectiveness study of a large real-world US dataset suggest that early initiation of sacubitril/valsartan in patients with de novo HFrEF is associated with lower rates of all-cause hospitalizations, CV hospitalizations and HF hospitalizations compared with ACEi or ARB. These findings reinforce the benefits observed in prospective clinical trials and extend the data supporting the use in a diverse, real-world cohort of US patients. Early optimization of therapy, including the use of sacubitril/valsartan, shortly after de novo HFrEF diagnosis, should be considered.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Gabriella Farries (Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland) for her contribution in the statistical analysis and critical review of the manuscript and Tripti Sahu (Novartis Healthcare Pvt. Ltd., India) for providing medical writing support in accordance with the Good Publication Practice (GPP) 2022 guidelines (https://www.ismpp.org/gpp-2022).

Conflict of interest statement

ASB has received research grant support to his institution from the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging, American College of Cardiology Foundation, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and consulting fees from Sanofi Pasteur, Merck and Novo Nordisk. MV has received research grant support, served on advisory boards or had speaker engagements with American Regent, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer AG, Baxter Healthcare, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cytokinetics, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pharmacosmos, Relypsa, Roche Diagnostics, Sanofi and Tricog Health and participates on clinical trial committees for studies sponsored by AstraZeneca, Galmed, Novartis, Bayer AG, Occlutech and Impulse Dynamics. BPJ, SS, CE and HS are employees of Novartis. MS is a consultant with Novartis, Merck, Bayer, Vifor Pharma, Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, BioVentrix, Servier, Novo Nordisk, Cardurion and AnaCardio.