Transcoronary study of biomarkers in patients with heart failure: Insights into intracardiac production

Jie Ren, Junhan Zhao and Shengwen Yang contributed equally to the study.

Abstract

Aims

Biomarkers are pivotal in the management of heart failure (HF); however, their lack of cardiac specificity could limit clinical utility. This study aimed to investigate the transcoronary changes and intracardiac production of these biomarkers.

Methods

Transcoronary gradients for B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and five novel biomarkers—galectin-3 (Gal-3), soluble suppression of tumourigenicity 2 (sST2), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1), growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF-15) and myeloperoxidase (MPO)—were determined using femoral artery (FA) and coronary sinus (CS) samples from 30 HF patients and 10 non-HF controls. Intracardiac biomarker production was assessed in an HF canine model using real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) and western blot (WB) analysis.

Results

Compared with the control group, levels of all detected biomarkers were significantly elevated in the HF group, while transcoronary gradients were only observed for BNP, Gal-3 and TIMP-1 levels in the HF group (BNP: FA: 841.5 ± 727.2 ng/mL vs. CS: 1132.0 ± 959.1 ng/mL, P = 0.005; Gal-3: FA: 9.5 ± 3.0 ng/mL vs. CS: 19.7 ± 16.4 ng/mL, P = 0.002; and TIMP-1: FA: 286.7 ± 68.9 ng/mL vs. CS: 377.3 ± 108.9 ng/mL, P = 0.001). Real-time qPCR and WB analysis revealed significant elevation of BNP, Gal-3 and TIMP-1 in the cardiac tissues of the HF group relative to other groups.

Conclusions

This study provided evidence of transcoronary changes in BNP, Gal-3 and TIMP-1 levels in HF patients, offering insights into their intracardiac production. These findings enhance the understanding of the biology of these biomarkers and may inform their clinical application.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) afflicts estimated 37.7 million individuals worldwide, representing 1%–2% of the adult population, imposing a substantial burden on public health systems and individual patients.1, 2 Arrhythmias are integral to the clinical presentation of HF pathogenesis, with supraventricular and ventricular tachyarrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation (AF) and premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), being potential to trigger or exacerbate HF.3, 4 These conditions cause electrical and mechanical dyssynchrony, leading to ventricular dysfunction and HF progression.5 Animal models confirm these findings, showing that sustained tachycardia induces HF-like symptoms, including left ventricular (LV) dysfunction. Effective arrhythmia management reverses LV dysfunction, improves clinical outcomes, and enhances quality of life and prognosis in HF patients.6

In recent years, the exploration of biomarkers has garnered significant attention due to their potential to aid in the diagnosis, severity assessment, risk stratification and treatment guidance of HF.7 B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-proBNP) are well-established biomarkers for HF, predominantly produced by cardiomyocytes in response to myocardial stretch.8 However, the utility of BNP or NT-proBNP can be confounded by conditions such as kidney disease, liver disease and obesity. HF is now recognized as a systemic disease characterized by a complex interplay between myocardial factors, systemic inflammation, renal dysfunction and neurohormonal activation.9 Over the past two decades, a plethora of novel biomarkers related to these aspects of HF pathophysiology have emerged.10, 11 Despite their specificity to certain pathways, the tissue specificity of these biomarkers remains incompletely understood, leaving uncertainty regarding whether they reflect systemic or regional pathological responses, which could limit their clinical applicability.12, 13

To address this knowledge gap, we evaluated the transcoronary gradients of BNP and five novel biomarkers—galectin-3 (Gal-3), soluble suppression of tumourigenicity 2 (sST2), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1), growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF-15) and myeloperoxidase (MPO)—in patients with HF and non-HF controls. And we further assessed the gene/protein expression levels of the above biomarkers in the cardiac tissue specimens from different chambers of the hearts in a canine model of HF.

Methods

Human study design and population

In total, 40 subjects who underwent electrophysiological interventional therapy at our hospital between June 2018 and June 2019 were enrolled. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age <18 years; (2) systemic complications, such as malignant tumour, autoimmune disease, endocrine disease or end-stage renal dysfunction; and (3) blood-borne infectious diseases, such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Clinical status was used to classify patients into two groups: (1) patients with HF-associated symptoms and an LV ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤40% (HF group) and (2) patients diagnosed with AF or supraventricular tachycardia undergoing catheter ablation, with no evidence of HF (control group). Clinical parameters, including biochemistry, and echocardiographic parameters were obtained from the electronic health records. The levels of BNP, galectin 3 and TIMP-1 in the artery blood samples of healthy volunteers (samples were obtained from our previous research cohort14) were measured and compared with those of our HF patients and the controls.

All participants provided written informed consent. This study conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital (2013-496).

Sample collection and preparation

Blood samples (3–4 mL) from the femoral artery (FA) and coronary sinus (CS) were simultaneously collected using EDTA VACUETTE tubes (Greiner Bio-One, Thailand). The samples were immediately centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The plasma (supernatant) was immediately separated and stored at −80°C until use.15

Biomarker measurement

Plasma levels of the six biomarkers were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits according to the manufacturer's instructions, as follows: Human BNP ELISA Kit (Abcam, ab193694), Human Galectin-3 Quantikine ELISA Kit (RD, DGAL30), Human GDF-15 Quantikine ELISA Kit (RD, DGD150), Myeloperoxidase Human Instant ELISA Kit (Invitrogen, BMS2038INST), Human ST2/IL-33R Quantikine ELISA Kit (RD, DST200) and Human TIMP-1 ELISA Kit (Abcam, ab100651). In this study, transcoronary changes were calculated as the difference between the FA and the CS.

HF model establishment

Seventeen male beagles (12 months old; 11–13 kg) were randomly assigned to the sham (N = 5), HF (N = 6) or therapy group (N = 6). One week after settling, all beagles underwent echocardiography and electrocardiography (ECG). Beagles in the HF and therapy groups underwent cardiac pacemaker implantation, while those in the control group underwent a sham operation.

Animals were anaesthetized using intravenous pentobarbital (3%; 30 mg/kg). Under fluoroscopy, the atrial lead was implanted into the right auricle, a ventricular passive lead (7231, Shanghai Lepu Medical Instrument Co., Ltd.) was implanted in the apex of the right ventricle and a ventricular active lead (7211, Shanghai Lepu Medical Instrument Co., Ltd.) was implanted in the septum. The leads were connected to a pacemaker placed subcutaneously on the right thoracic wall. After the operation, pacemakers were turned on using a programming instrument (QM2352A, dual-chamber pacing system analyser, Shanghai Lepu Medical Instrument Co., Ltd.). Pacing was continued for 6 weeks (pacing mode, AOO; pacing frequency, 250 times/min; output, 3.6 V; and pulse width, 0.4 ms). To prevent infection, beagles were injected with 80 U penicillin intramuscularly twice a day for 7 days and fed with a high-protein diet.

After 6 weeks of pacing, follow-up echocardiography and ECG were performed. Subsequently, in the therapy group, pacemakers were replaced with a cardiac contractility modulation (CCM) device (Optimizer II; Impulse Dynamics, USA), which enhances contractility and is beneficial for HF treatment. The parameters were set as follows: pulse width, 2 ms; output voltage, 7 V; R-wave delay, 30 ms; and stimulation, 6–8 h every day. After 1 week, echocardiography and ECG were repeated.

Animal study

The experimental animals were euthanized, hearts were flushed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before excision and cardiac tissue samples were harvested. Tissue samples were washed with cold PBS to remove the blood and were quickly snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. All animal experiments complied with the ARRIVE guidelines and were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health's (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital (FW-2022-0051).

Pathology and molecular biology methods are described in the supporting information.

Statistical analysis

For the clinical characteristics, continuous variables are shown as mean [standard deviation (SD)] or median [with inter-quartile range (IQR)], as appropriate, while categorical variables are shown as number (percentage). Between-group comparisons were performed using Student's t test for normally distributed and the Kruskal–Wallis test for non-normally distributed continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson's χ2 test. Spearman's test was used for correlation calculation. Data were analysed using STATA 15.0. Plots were generated through Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Clinical characteristics in HF patients

In this study, a cohort of 30 patients with HF and 10 healthy controls were enrolled. The clinical characteristics are detailed in Table 1. HF patients were stratified according to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification, with Classes II–IV, while the control group comprised individuals with normal cardiac function. There were significant differences between HF patients and controls in left atrial diameter [LAD, 42.0 (38.0–45.0) vs. 34.0 (31.0–36.0) mm, P < 0.01, data shown as the median with IQR] and LV end-diastolic dimension (LVEDD, 67.3 ± 9.5 vs. 45.7 ± 3.2 mm, P < 0.01). Moreover, the LVEF was markedly lower in the HF group, with a mean value of 30.5% (IQR: 26.0–38.0) compared with 62.5% (IQR: 62.0–66.0) in the controls (P < 0.01). Additionally, the plasma levels of NT-proBNP were significantly elevated in HF patients, with a median value of 941.5 (IQR: 374.9–2114.0) pg/mL versus 29.4 (IQR: 14.8–82.7) pg/mL in the control group (P < 0.01). No significant differences were noted between the two groups in the remaining evaluated parameters.

| Characteristics | Control group (n = 10) | HF group (n = 30) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 52.5 (5.2) | 58.7 (10.3) | 0.08 |

| Sex (male) | 7 (70.0%) | 22 (73.3%) | 0.84 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 23.9 (3.2) | 25.3 (3.6) | 0.31 |

| Systolic pressure (IQR) | 119.0 (98.0–128.0) | 115.0 (97.0–126.0) | 0.62 |

| Diastolic pressure (IQR) | 70.0 (61.0–81.0) | 72.0 (64.0–82.0) | 0.74 |

| Alcohol history | 2 (20.0%) | 8 (26.7%) | 0.67 |

| Smoker | 4 (40.0%) | 13 (43.3%) | 0.85 |

| NYHA classification | |||

| I | 10 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.01 |

| II | 0 (0.0%) | 16 (53.3%) | |

| III | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (40.0%) | |

| IV | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (6.7%) | |

| Echocardiography | |||

| LAD, median (IQR) | 34.0 (31.0–36.0) | 42.0 (38.0–45.0) | <0.01 |

| IVS, mean (SD) | 9.2 (1.2) | 8.7 (1.3) | 0.32 |

| LVEDD, mean (SD) | 45.7 (3.2) | 67.3 (9.5) | <0.01 |

| LVEF, median (IQR) | 62.5 (62.0–66.0) | 30.5 (26.0–38.0) | <0.01 |

| RV, median (IQR) | 22.5 (18.0–24.0) | 23.0 (20.0–25.0) | 0.42 |

| Albumin, mean (SD) | 44.6 (2.1) | 43.6 (3.6) | 0.41 |

| ALT, median (IQR) | 20.0 (14.0–24.0) | 20.0 (16.0–28.0) | 0.79 |

| CREA, mean (SD) | 76.5 (16.3) | 87.8 (17.4) | 0.08 |

| CK-MB, mean (SD) | 12.4 (3.2) | 11.0 (4.9) | 0.41 |

| TC, mean (SD) | 4.9 (1.2) | 4.1 (1.1) | 0.06 |

| NT-proBNP, median (IQR) | 29.4 (14.8–82.7) | 941.5 (374.9–2114.0) | <0.01 |

- Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; CK-MB, creatine kinase MB; CREA, creatinine; HF, heart failure; IQR, inter-quartile range; IVS, interventricular septum; LAD, left atrial diameter; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RV, right ventricle; TC, total cholesterol.

Plasma biomarker levels and transcoronary changes of HF biomarkers

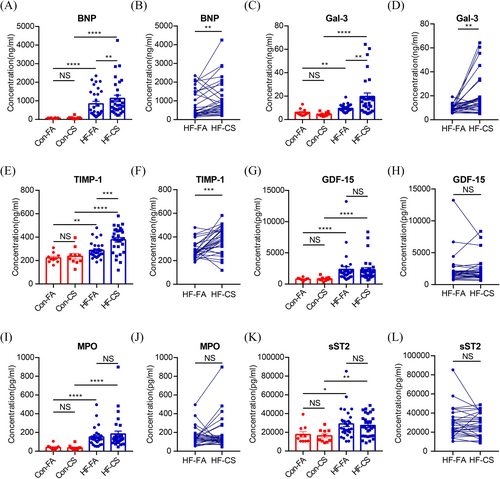

There were no significant differences in the biomarker between the control and healthy populations. This finding underscores the representativeness of our control group (Figure S1). In comparison with the control group, the HF group exhibited significantly elevated levels of BNP in both the FA and CS samples (Figure 1A; FA: 841.5 ± 727.2 vs. 67.9 ± 21.3 ng/mL, P < 0.0001; CS: 1132.0 ± 959.1 vs. 90.40 ± 67.5 ng/mL, P < 0.0001, respectively). Notably, the control group did not exhibit a transcoronary gradient for BNP, whereas the CS levels were significantly higher than the FA levels in the HF group (Figure 1B, 1132.0 ± 959.1 vs. 841.5 ± 727.2 ng/mL, P = 0.005). As well, Gal-3 and TIMP-1 levels were markedly increased in the HF group compared with the control group across both FA and CS measurements (Figure 1C, Gal-3: FA: 9.5 ± 3.0 vs. 6.2 ± 3.1 ng/mL, P = 0.004; CS: 19.7 ± 16.4 vs. 4.6 ± 1.6 ng/mL, P < 0.0001; Figure 1E, TIMP-1: FA: 286.7 ± 68.9 vs. 223.1 ± 43.0 ng/mL, P = 0.0028; CS: 377.3 ± 108.9 vs. 237.7 ± 75.5 ng/mL, P = 0.0007, respectively). And transcoronary gradients for Gal-3 and TIMP-1 were also observed only in the HF group (Figure 1D, Gal-3: FA: 9.5 ± 3.0 vs. CS: 19.7 ± 16.4 ng/mL, P = 0.002; Figure 1F, TIMP-1: 286.7 ± 68.9 vs. 377.3 ± 108.9 ng/mL, P = 0.001). These results suggest that cardiac tissue could produce BNP, Gal-3 and TIMP-1, which are released into the circulation in HF settings. Although the HF group had significantly higher FA and CS levels of GDF-15 (Figure 1G,H, 782.7 ± 232.5 vs. 2338.0 ± 2373.0 pg/mL, P < 0.0001; 837.0 ± 326.8 vs. 2302.0 ± 1838.0 pg/mL, P < 0.0001), MPO (Figure 1I,J, 39.5 ± 27.5 vs. 152.2 ± 95.3 ng/mL, P < 0.0001; 36.3 ± 26.3 vs. 183.7 ± 169.8 ng/mL, P < 0.0001) and sST2 (Figure 1K,L, 17 637.0 ± 9341.0 vs. 28 938.0 ± 15 507.0 pg/mL, P = 0.0137; 16 219 ± 6733 vs. 27 263 ± 11 663 pg/mL, P = 0.0068; respectively) than the control group, transcoronary gradients were not observed in either group, indicating no significant production or absorption of these biomarkers in the heart.

Correlation between biomarker gradients and clinical parameters

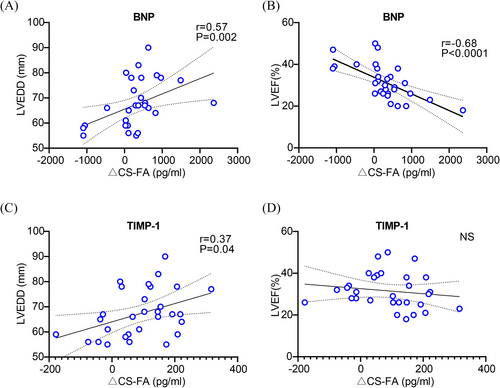

The correlation analysis unveiled a significant correlation between BNP levels and HF-associated clinical features, such as LVEF and LVEDD (Figure S2). Transcoronary BNP gradients also exhibited strong correlations with these clinical features (LVEF, r = −0.68, P < 0.0001; LVEDD, r = 0.57, P = 0.002) (Figure 2A,B). Notably, BNP levels did not correlate with blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, hepatorenal function indices, including alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, nor with inflammatory markers such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and cardiac troponin T (Figure S2). Also, significant correlations were observed between LVEDD and the transcoronary gradients of TIMP-1 (Figure 2C, r = 0.37, P = 0.04). Beyond these, no other significant correlations were found between other biomarker gradients and clinical characteristics (Figures S2 and S3). The findings revealed that BNP, as a biomarker for HF, is of great advantage for clinical applications.

Intracardiac production of HF biomarkers in HF model

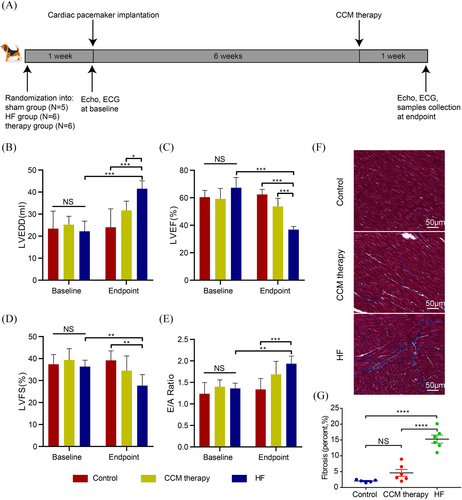

An illustrative schematic of the model development is depicted in Figure 3A. Dogs subjected to HF and CCM groups developed characteristic HF symptoms, such as diminished appetite, tachypnoea and reduced physical activity, at 6 weeks after induction. In contrast, the sham group remained asymptomatic throughout the study period. Baseline echocardiographic assessments revealed no significant intergroup differences. However, after 7 weeks, the HF group exhibited a marked decline in cardiac architecture and function, as evidenced by increased LVEDD, decreased LVEF, LV fractional shortening (LVFS) and an elevated E/A ratio compared with the control group (LVEDD: 41.5 ± 3.7 vs. 24.0 ± 8.3 mm, P < 0.0001; LVEF: 36.8 ± 2.3% vs. 62.4 ± 3.8%, P < 0.0001; LVFS: 27.7 ± 5.0% vs. 39.2 ± 4.3%, P = 0.001; and E/A ratio: 1.9 ± 0.18 vs. 1.3 ± 0.25, P = 0.003, Figure 3A–E). The HF dogs exhibited a partial restoration of cardiac mechanical function in response to CCM therapy (LVEDD: 31.7 ± 4.2 vs. 41.5 ± 3.7 mm, P = 0.01; LVEF: 53.6 ± 6.0% vs. 36.8 ± 2.3%, P < 0.0001; LVFS: 34.5 ± 6.7% vs. 27.7 ± 5.0%, P = 0.06; and E/A ratio: 1.7 ± 0.3 vs. 1.9 ± 0.18; P = 0.17; Figure 3B–E). As evidenced by histological staining, the HF group had an increased deposition of blue-stained collagen fibres in LV, whereas CCM therapy partially reversed the pathological changes (Figure 3F,G). All the above results confirmed the successful construction of the HF model, which provided a solid material basis for subsequent research.

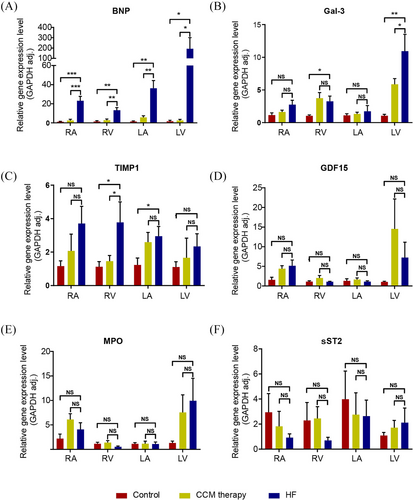

We employed real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) to quantify mRNA levels in distinct chambers of the heart. For concordance with the protein levels in plasmas as quantitated by ELISA, we found that the mRNA expression levels of BNP, Gal-3 and TIMP-1 were significantly elevated in the cardiac tissues of the HF group compared with those in other groups (Figure 4A–C). In the HF group, BNP expression was clearly elevated throughout the heart tissues (Figure 4A). Gal-3 expression was predominant in the LV, whereas the expression of TIMP-1 is predominantly localized to the right heart (Figure 4B,C). The gene expression of ST2, GDF-15 and MPO in the myocardium did not differ statistically significantly between the three groups (Figure 4D–F). These results were in agreement with the transcoronary changes observed in the ELISA study.

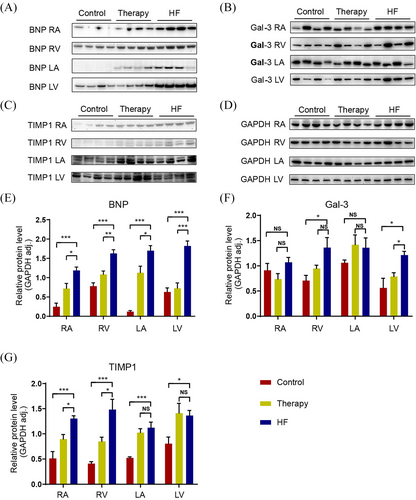

We performed western blot (WB) to assess the protein levels in myocardium in order to confirm the elevated expression of BNP, Gal-3 and TIMP-1 in HF cardiac tissues. As illustrated in Figure 5, the myocardium (all atrial and ventricular tissues) showed increased BNP expression in the HF group when compared with the control group (Figure 5A). Gal-3 protein expression was significantly higher in ventricular tissue of HF hearts, especially LV (Figure 5B). Same as reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) analysis of cardia tissues indicating, protein TIMP-1 expression is mainly elevated in the right heart (Figure 5C). And the gene expression signature of BNP, Gal-3 and TIMP-1 in HF cardiac tissues could at least partially reverse by administration of therapy for HF (CCM therapy) (Figure 5D–F).

Discussion

In order to ascertain the cardiac specificity of the modulated levels of circulating biomarkers observed in HF patients, we evaluated the transcoronary gradients of BNP and five additional HF biomarkers in patients. Furthermore, we assessed the expression levels of these biomarkers across different chambers of the heart in a canine model of HF. The data revealed that myocardial tissues under HF conditions are capable of synthesizing and releasing BNP, Gal-3 and TIMP-1 into the bloodstream. In contrast, the remaining biomarkers (sST2, GDF-15 and MPO) are likely to originate from extracardiac sources.

Plasma BNP level has been established as the gold standard biomarker for HF, widely used for diagnostic, monitoring and therapeutic management in HF patients. In our study, the transcoronary gradient of BNP was found to be significantly correlated with LVEF and LVEDD, suggesting that BNP levels are associated with the mechanical wall stress of the heart. We further substantiated the intracardiac production of BNP in the animal model, with the left ventricle being the primary site of BNP synthesis. The cardiac specificity of BNP may underpin its broad utilization in the clinical setting of HF.16, 17

Cardiac fibrosis emerges as a central pathophysiological process in HF. Gal-3 and TIMP-1 have been identified as pivotal players in myocardial remodelling.18 Gal-3 is a lectin that specifically binds to β-galactosides and is widely expressed across various human tissues.19 The expression of Gal-3 is observed in activated macrophages, basophils, mast cells, endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, sensory neurons and certain epithelial cells.20 In the heart, Prud'homme et al. found that Gal-3 expression is triggered by the recruitment of bone marrow-derived immune cells.21 Gal-3 has been shown to correlate strongly with biomarkers of cardiac extracellular matrix (ECM) turnover, such as the amino-terminal propeptide of type III procollagen (PIIINP), TIMP-1 and matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2).22 Moreover, Gal-3 has been established as an independent prognostic indicator for long-term all-cause mortality in HF patients.23, 24 However, the expression of Gal3 in cardiomyocytes and its precise localization in cardiac tissue require further elucidation. TIMP-1 plays a pivotal role in modulating the ECM by inhibiting the activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).25 In paediatric subjects with a single ventricle with right ventricular (RV) failure, TIMP-1 expression is markedly altered.26 Moreover, a study encompassing 25 subjects who underwent pulmonary endarterectomy (PEA) revealed a correlation between the amelioration of RV function and the fluctuating levels of TIMP-1.27 In patients with repaired tetralogy of Fallot (rTOF), RV fibrosis is a common complication associated with elevated TIMP-1, which may serve as a reflection of RV fibrosis and is linked to negative clinical outcome markers.28 An MMP/TIMP-1 imbalance has been observed in end-stage HF,29 and it is also an independent predictor of all-cause death in HF patients. Elevated levels of TIMP-1 were also found to correlate with deteriorating systemic RV function and to predict adverse clinical outcomes, underscoring its prognostic significance.30 Our findings indicate a significant increase in transcoronary levels of Gal-3 and TIMP-1 in HF patients. This suggests that Gal-3 and TIMP-1 may play a role in the pathogenesis of HF, warranting further in-depth investigations to elucidate their precise mechanisms of action in the progression of the disease.

In recent years, HF has been recognized as a systemic illness, with a variety of pathways and pathological processes involved, including inflammation, renal dysfunction and activation of neurohormones.31-33 In spite of many of the HF biomarkers representing specific pathways, there is no clear understanding of their significance, tissue specificity. In our study, the plasma levels of sST2, GDF-15 and MPO increased in the circulation in patients with HF; while, there was no net transcoronary gradient, indicating that the increased levels did not rely on cardiac release.

sST2 acts as a decoy receptor for interleukin-33 (IL-33). This interaction is significant in the context of immune responses and inflammation.34 Studies have implicated the vascular endothelium in both the liver and lungs as potential contributors to the elevation of serum sST2 levels.35 Notably, the IL-33/ST2 signalling axis is particularly active in the endothelium of arterial vessels, highlighting its relevance in vascular biology.36 This comprehensive distribution and response pattern indicate that sST2 is a key player in the body's response to injury and inflammation, with significant implications for cardiovascular health and disease.37 GDF-15, a stress response cytokine, exhibits elevated expression levels in response to diverse cellular stressors, including inflammation, hypoxia, tissue damage, myocardial ischaemia and malignancies.38 The highest expression of GDF-15 is observed in the kidney, followed by the liver. During inflammation and organ injury, GDF-15 expression is up-regulated across nearly all liver cell types, with a marked increase in cholangiocytes and endothelial cells.39 Collectively, these findings suggest that the liver plays a significant role in modulating the circulating levels of GDF-15, potentially serving as a key tissue in the regulation of this cytokine's systemic response to stress. MPO, an enzyme predominantly found in human polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) and monocytes, plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of vascular inflammation and endothelial dysfunction.40, 41 MPO catalyses the production of reactive species, thereby contributing to endothelial dysfunction. This enzyme has been detected in the endothelium and subendothelial space in various human inflammatory conditions, suggesting its involvement in the local vascular redox environment. MPO's activity can subtly alter this redox state, leading to significant shifts in cellular signalling pathways, which are essential for the manifestation of vascular inflammatory disease phenotypes. Consequently, pharmacological inhibition of MPO is considered a promising therapeutic approach to mitigate endothelial dysfunction associated with vascular inflammation.42

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we did not have data on mRNA and protein expression in patients with HF, as tissue samples are rare and difficult to acquire. Second, transcoronary gradients were not measured in the canine model because of the lack of available commercial kits for dogs. Third, although cardiac magnetic resonance imaging may provide more information on cardiac structure and myocardial pathology, it was not available for most patients in this study; therefore, we used echocardiography parameters instead.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we provided direct evidence of transcoronary changes in six biomarkers in patients with HF, as well as insight into their origin. Our findings provide a better understanding of the biology of these putative biomarkers, promoting their use in clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (2024BZR-7242126), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82400430) and National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding, Elite Medical Professionals Project of China-Japan Friendship Hospital (ZRJY2021-QM18)

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Open Research

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.