Psychiatric disorders in adolescent cancer survivors: A systematic review of prevalence and predictors

Abstract

Background

Adolescent cancer survivors are a particularly vulnerable group of young patients. Compared with healthy peers, adolescent survivors face more psychosocial difficulties and are at increased risk of developing psychiatric disorders.

Aims

We aimed to establish prevalence rates and predictors of psychiatric disorders in young cancer survivors and discuss areas for targeted interventions.

Method

We systematically reviewed four major online databases: Embase, PsychINFO, Scopus, and Medline for quantitative studies evaluating mental health in adolescent cancer survivors. We used a narrative synthesis approach.

Results

Nineteen studies met our inclusion criteria. Across the sample, up to 34% met criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 13% for clinical depression, and 8% for anxiety. Maladaptive coping, illness relapse, higher number of late effects, brain tumor diagnosis, and poor family functioning and parental distress were associated with higher psychological distress.

Conclusions

A significant subset of adolescent survivors reports PTSD, anxiety, and depression symptoms. Individuals who present with more vulnerabilities and higher risk indices should be routinely assessed in order to reduce the psychological, social, and economic burden associated with poor mental health in this population. Early prevention strategies should target maladaptive coping mechanisms and promote healthy peer relationships and family functioning.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cancer diagnosis and treatment are a stressful and traumatic experience for a patient of any age. However, patients facing cancer at different developmental stages might face distinct challenges. Advances in modern medicine raised the survival rates of childhood cancer* well beyond 80%.1 However, adolescents as a subgroup of childhood cancer patients have seen slower improvement2 and may face more psychosocial difficulties during and after their cancer treatment.3-5 Adolescent patients and survivors present with unique needs due to the nature of their developmental period. Cancer can disrupt normative cognitive development,6 interfere with social activities,7 and impose new demands on the survivor and their family.8, 9 Feelings of distress, anxiety, and depression are a common response at the time of cancer diagnosis10 and tend to subside with time.11, 12 However, a smaller, yet significant, subset of childhood cancer survivors do report a spectrum of adverse outcomes including poorer physical health,13 difficulties in relationships,14 somatic complaints,15, 16 and psychopathology.17-19

Due to methodological obstacles, the exact prevalence rates of psychopathology in adolescent cancer survivors are hard to establish. For the purposes of this review, we consider adolescent survivors to be between 10 and 23 years of age, off cancer treatment, and free of disease. In the existing literature, studies employ various age cutoffs, in part due to the diverging views on how to define adolescent period, and some researchers group adolescents with younger children, while others group them with adults,20 thus the specified age range was agreed upon between authors to capture an optimal sample.

2 ADOLESCENTS, TRAUMA, AND PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

Adolescence is not only a time of rapid growth and psychosocial development21-24 but also the time when most of the psychiatric disorders first arise. The onset of most psychiatric disorders peaks at 14 years of age25 with estimated risks growing higher in late adolescence and early adulthood.26 In population-based samples, anxiety disorders among adolescents tend to be more prevalent, around 31%,26 compared with depression, which is between 4% and 5%.27 Some findings suggest that most of adolescent psychiatric disorders resolve by the late 20s. However, a significant subset of those who have had at least one episode during adolescence, continue to report mental health difficulties throughout their 20s.28

During adolescence, significant or chronic stressors can derail the normative development and trigger psychopathology or contribute to life-long psychiatric disorders.29 Diagnosis and treatment for cancer may be considered as a form of trauma and, as such, impact one's development and psychological well-being. Cancer might even share common biological pathways to the expression of common psychiatric disorders.30 In adult cancer survivors, the rates of depression and anxiety are higher when compared with their spouses or healthy adults30, 31; however, the findings in adolescent survivors are inconclusive.

3 PREDICTORS OF PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

The etiologies of psychiatric disorders are multifactorial, with biological, individual, and societal factors contributing varying degrees of risk. Heritability estimates suggest that between 30% and 40% of variance in depression and anxiety are attributable to genes,32, 33 while the rest can be attributed to environmental causes, including stressful experiences. Childhood cancer patients might endure significant stress as a result of treatment or of the illness itself; however, stress alone might not predict psychological ill health. Research suggests that the developing brain under stress might sustain anatomical and functional changes, which can lead to higher stress reactivity, and consequently to psychiatric disorders.34 Additionally, stress can impair emotion regulation, and cognitive functioning, which can result in maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as rumination or avoidance.34, 35 These maladaptive coping styles have been associated with higher levels of psychological distress and more depressive symptomatology in adult cancer survivors.36, 37 Moreover, risky family environment, marked by emotionally cold and distant relationship, can interact with other biological factors and lead to the development of maladaptive behaviors and psychiatric disorders in the offspring.38

To date, no systematic review evaluated the prevalence and predictors of psychiatric disorders in adolescent cancer survivors. A better understanding of adolescent mental health through cancer survivorship, as well as the risk and protective factors, will allow for development of targeted therapeutic approaches. Thus, the aims of this systematic review were the following: (1) to establish the prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders in adolescent cancer survivors and (2) to systematically review and identify the predictors of psychiatric disorders in the specified population and compare it to healthy peers.

4 METHOD

4.1 Design

A systematic review of the literature was conducted.

4.2 Search

Our search strategy was developed in tandem with a librarian within our department. Via Ovid search platform, we conducted searches in Embase, PsychINFO, Scopus, and Medline for articles examining the association between cancer survivorship and psychopathology from earliest point available through 20 January 2018. Our search terms were (child* OR adolesc*OR p*ediatric).ab. AND (child* OR adolesc* OR p*ediatric) ti. and (cancer or neoplasm or tumor or leuk*emia or lymphoma).ab. AND (cancer OR neoplasm OR leuk*emia OR lymphoma) ti. AND (depress* OR distress OR dysphoria OR dysthym* OR affective disorder OR mood disorder OR psychopathology OR psychiatric morbidity OR PTSD OR post-traumatic stress disorder OR adjustment OR anxiety OR suicide OR self-harm) ab. Additionally, reference lists were examined in order to retrieve any relevant papers not found in our initial search.

4.3 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In order to be included in our systematic review, the studies had to satisfy the following inclusion criteria: (a) they had to be quantitative studies that looked at adolescent survivors of childhood cancer of any type, from any country, and of any type of research setting; (b) the adolescent sample had to be between 10 and 23 years of age, with the mean age between 10 and 20 years; (c) the mean age at first diagnosis had to be 5 years or older; (d) participants were disease free at the time of the study and off-treatment for a mean of at least 12 months; (e) the study employed a validated measure of psychopathology based on past or present DSM or ICD criteria for mental disorders; and (f) the measures had to rely on self-reports by adolescent cancer survivors or clinician rating. Studies were excluded based on the following criteria: (a) if the full text was not available in English, (b) case-report studies, (c) if they relied solely on qualitative methods, (d) if they employed only proxy measures of psychopathology (eg, self-esteem and worry), and (e) if they only reported parental reports. In order to limit potential bias in sample representativeness, we excluded intervention studies that only recruited participants based on some predetermined cutoff scores for a psychiatric disorder.

4.4 Data extraction

Data were extracted by U.K. and M.W. independently. We extracted authors' names, year of publication, and titles. We also recorded sample characteristics with demographic information that was relevant for our analyses, information about cancer and treatment, measures of psychopathology, and other measures employed, overall findings, and conclusions of each paper. If two or more papers used the same sample, the study that reported more data relevant to the aims of this review was included. Authors of the studies that did not report relevant information were contacted to provide the missing data. If no answer was received upon two attempts of contact, the study was excluded.

4.5 Quality appraisal and data analysis

U.K. and M.W. independently assessed the quality of the studies in the final sample using shortened version of Downs and Black Quality Checklist.39 Any inconsistencies were resolved in consensus meetings. The quality checklist has been utilized in previously published reviews.3, 4 The modified version employs nine criteria, rated and scored as either “Yes” (1) or “No/Unable to determine” (0). Studies that received a rating of 8 or above were considered to be of high quality.

Aims of the current review were addressed by carrying out a narrative synthesis approach. Prevalence rates were extracted from individual studies wherever reported. In order to establish predictors, we extracted and evaluated variables that were significantly associated with psychiatric disorders within individual studies. Effect sizes were calculated and reported where possible.

5 RESULTS

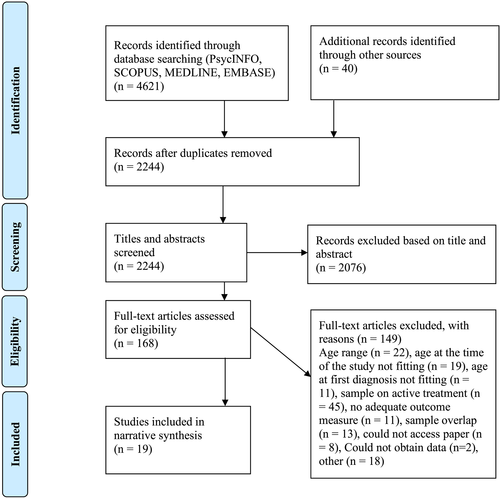

Our literature search yielded 2245 unique articles of which we reviewed titles and abstracts for relevance against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. For the remaining 168 articles, the full text was reviewed and 149 excluded (See Figure 1 for more details). The 21 articles that met our criteria were evaluated and data extracted from them. We contacted two authors, one of whom reported not having the requested data and another who had moved and no longer had access to the original study results. The final sample included in this review consisted of 19 articles. Meta-analysis was not performed due to high heterogeneity of analytic and outcome measurement approaches, cancer subtypes, and lack of control groups in 13 out of 19 studies.

Characteristics of the participants, type of cancer, and the main findings of the studies included in this review are summarized in Table 3. The mean sample age ranged from 13.7 to 20.2 years (M = 16.3 years), and the mean sample age at the time of cancer diagnosis ranged from 5 to 13.7 years (M = 8.4 years, range = 3 months to 18 years).

All studies that met our inclusion criteria were cross-sectional in nature, and most recruited their participants through tumor registries and at follow-up clinics. The sample sizes ranged from 21 to 407 young cancer survivors. Nine studies reported on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), four of which used self-reported measures and three clinical interviews by a trained professional. Two studies used multiple measures to assess PTSD. Eight studies assessed depression, and eight measured anxiety among adolescent cancer survivors, six of those measured both outcomes simultaneously. All studies employed self-report measures, and one included a clinician administered diagnostic interview. Details about the measures can be found in Tables 1 and 2.

| Measure Name | Measure Description | Used in |

|---|---|---|

| Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Epidemiologic Version-5 (K-SADS-E-5; Orvaschel, 1995) | Semistructured diagnostic interview | Robinson et al52 |

| Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R; Weiss & Marmar, 1997) | 22-item self-report questionnaire | Kazak et al19; Ozono et al49 |

| Child PTSD Symptom Scale (CPSS; Foa, Johnson, Feeny, & Treadwell, 2001) | 17-item self-report questionnaire | Cousino et al17 |

| University of California at Los Angeles Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index (UCLA-RI; Pynoos et al., 1998) | 22-item self-report questionnaire | Michel et al48 |

| Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)—nonpatient edition of the SCID (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995) | Structured diagnostic interview | Kazak et al19; Alderfer et al40; Pelcovitz et al50 |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index (PTSD-RI; Pynoos, Fred-erick, Nader, & Arroyo, 1987) | 20-item self-report questionnaire | Kazak et al19; Brown et al43 |

| Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for Children and Adolescents (CAPS-CA; Newman et al., 2004) | Semistructured diagnostic interview | Erickson et al45 |

| Child Posttraumatic Stress Reaction Index Revision 2 (CPTS-RI Revision 2; Steinberg & Pynoos, 2001) | 30-item self-report questionnaire | Erickson et al45 |

| Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children-Alternate version (TSCC-A; Briere, 1996)a | 44-item self-report questionnaire | Erickson et al45 |

- a The measure also assessed depression and anxiety in addition to trauma symptoms (ie, dissociation).

| Measure Name | Measure Description | Used by |

|---|---|---|

| Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1985) | 27-item self-report questionnaire | Ozono et al49 |

| Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18; Derogatis, 2001) | 18-item self-report questionnaire | Gianinazzi et al18 |

| Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983) | 53-item self-repot questionnaire | Turner-Sack et al54 |

| Children's Depression Rating Scale (CDRS; Poznanski et al., 1984) | 16-item clinician administered scale | Fritz and Williams46 |

| Behavior Assessment System for Children-2nd Edition Self-Report (BASC-2; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004) | Self-report measure | Cousino et al17; Carpentieri et al44 |

| Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale-Short Form (RADS2-SF; Reynolds, 2002) | 10-item self-report questionnaire | Yallop et al55 |

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) | 20-item self-report questionnaire | Bitsko et al42 |

| Clinical interview based on DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000) | Semistructured interview | Liptak et al47 |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger et al., 1970) | 40-item self-report questionnaire | Ozono et al49; Servitzoglou et al53; Bauld et al41 |

| Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children-short form (MASC-10; March et al., 1997) | 10-item self-report questionnaire | Yallop et al55 |

| Social Anxiety Scale for Children-Revised (SASC-R; La Greca, 1992) | 22-item self-report questionnaire | Pendley et al51 |

| The Beck Youth Inventories-II (BYI-II; Beck et al., 2005) | 20-item self-report questionnaire | Liptak et al47 |

Seven of the studies excluded brain tumor survivors, and two assessed only brain tumors survivors. The majority of the research had been conducted in the United States, while Canada, United Kingdom, Switzerland, Greece, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan each contribute one study (see Table 3).

| Reference | Country | Quality Rating | Aims of the Study/Psychopathology Measured | N | Age at the Time of the Study M (SD) [range] | Age at Diagnosis M (SD) [range] | Time Off Treatment M (SD) [range] | Cancer Specifics | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alderfer et al40 | United States | 8 | To investigate the relationship between family functioning and PTSD in adolescent survivors | 144 | 14.6 (2.4) [11-19 years] | 7.8 years (4.3) [3 months-16.4 years] | 5.3 (2.9) [1-12 years] | Leukemia (31%), solid tumor (22%), lymphoma (22%), bone tumors (8%), other (17%) | 8.3% of survivors met PTSD criteria and did not differ in cancer diagnosis or age at diagnosis from those without PTSD. Survivors with PTSD were five times more likely to emerge from families with poor functioning. |

| Bauld et al41 | Australia | 6 | To assess psychosocial functioning (anxiety) in adolescent cancer survivors and compare it to healthy peers | 32 | 14.9 (1.6) [12-17 years] | 7.5 years | 8 years | Brain tumors excluded, predominantly ALL | Survivors reported higher state anxiety than healthy controls but were overall less anxious. Survivors employed more maladaptive coping mechanisms such as wishful thinking and avoidance. |

| Bitsko et al42 | United States | 7 | To test whether happiness and time perspective mediate positive psychosocial adjustment (depression) to adolescent cancer survivorship | 50 | 20.2 [10-21 years] | 13.7 [10-21 years] | 53.9 months (30.5) | Leukemia (26%), lymphoma (38%), other (36%) | Happiness is a stronger predictor of depression than intensity of treatment. Thinking negatively about one's past is stronger predictors about depression than female gender. |

| Brown et al43 | United States | 6 | To examine PTSD in adolescent survivors and their mothers and compare it to healthy controls, and to assess contribution of family functioning to PTSD levels | 52 | 17 (3.4) [13-23 years] | 9.4 (4.9) [1.1-18.5 years] | 11.4 (4.6) [3.1-19.5 years] | Brain tumors excluded, leukemia (51.9%), other solid tumors (48.1%) | None of the survivors met full-PTSD criteria, 36% endorsed subclinical levels; 25% of survivors' mothers met PTSD criteria. Late effects contributed to survivors' PTSD symptomatology. |

| Carpentieri et al44 | United States | 8 | To describe the psychosocial and behavioral functioning in adolescent survivors via self-report, as well as parent and teacher report (using BASC) | 31 | 14.5 [12-18 years] | 8.8 (median = 10) [2-15 years] | 4.1 (median = 3) [1.5-12 years] | Only brain tumor cases | 6.5% and 3.2% of adolescent brain survivors reported depression and anxiety, respectively. Parents of these survivors reported problems with attention and leadership, while teachers reported problems in learning. |

| Cousino et al17 | United States | 8 | To examine associations between survivor's late effects, illness specific family burden and emotional and behavioral outcomes (BASC and PTSD) | 65 | 14.1 (2.1) [10-17 years] | 6.2 (3.5) years | 6.2 (2.8) years | ALL (36.9%), AML (6.2%), brain/CNS tumor (26.2%), neuroblastoma (4.5%), Hodgkin lymphoma (1.5%), soft tissue (6.2%), bone cancer (3.1%), nonmalignant brain tumor (12.3%) | 33.8% of survivors endorsed clinically significant levels of PTSD. PTSD reported greater late effects. |

| Erickson et al45 | United States | 6 | To examine the repressive adaptive style and its influence on psychosocial adaptation in adolescent cancer survivors | 29 | 15.3 (1.82) [12-18 years] | 6.2 (4.4) years | Minimum 1 year, not further specified | Brain tumors excluded, leukemia (31%), lymphoma (21%), solid tumor (24%), sarcoma (14%), other (10%) | 13.8% of all survivors qualified for PTSD diagnosis, all were nonrepressors. Nonrepressors reported poorer QOL, higher anxiety and depression, more variability in PTSD, and heightened total problems. The differences were non-sig. |

| Fritz and Williams46 | United States | 4 | To assess the psychological adjustment (depression) in adolescent cancer survivors | 41 | 17.3 (3.1) [13-21 years] | 11 (3.6) years | 2-8 years | Brain tumors excluded, leukemia (34%), Hodgkin disease (21%), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (22%), bone sarcoma (10%), other (13%) | 7% of survivors reported clinical depression and 12% were in subclinical levels. 50% of the sample was preoccupied with their body, 27% were counter-phobic, and 26% were hypochondrical. |

| Gianinazzi et al18 | Switzerland | 9 | To examine psychological distress (BSI-18) and its risk factors in adolescent cancer survivors and compare it to siblings, norm, and psychotherapy patients | 407 | 17.9 (1.5) [16-19 years] | 5.7 (3.9) years | >5 years | Leukemia and lymphoma (46%), CNS (17%), other (37%) | 13% of survivors reported clinical distress compared with 11% of siblings. Higher distress in survivors was associated with female gender, somatic and psychological late effects, and low perceived parental support. |

| Kazak et al19 | United States | 6 | To describe rates of PTSD and PTSS in adolescent cancer survivors as well as their mothers and fathers | 150 | 14.7 (2.4) [11-19 years] | 7.9 (4.3) [3 months-16 years] | 5.3 (2.9) years | Excluded any case with relapse of illness, leukemia (30.5%), solid tumors (35.1%), lymphoma (21.2%), other (13.2%) | 8% of survivors met criteria for PTSD since diagnosis and 4.7% for current PTSD. Survivors reported high levels of arousal (41%), and re-experiencing (73%). |

| Liptak et al47 | United States | 7 | To assess self-reported brain tumor survivors' psychological well-being (depression, anxiety, and self-concept) and compare it to the outcomes of clinical interviews | 84 | 15.7 (1.9) [12-18 years] | 9.1 (4.9) years | >1 year | Only brain tumor cases | 17% of adolescent survivors reported clinical levels of depression and anxiety. The concordance between self-report and clinician ratings was low, with clinicians reporting higher distress than adolescents. |

| Michel et al48 | United Kingdom | 8 | To establish the contribution of medical and demographic factors to benefit finding and PTG I adolescent survivors and parents | 41 | 13.7 (1.1) [12-16 years] | 5 (3.0) [0-12 years] | 6.6 (2.9) [3-14 years] | Leukemia (50%), CNS (17%), solid tumor (33%) | PTSD symptomatology was not sig. associated with benefit finding in adolescent survivors. Diagnosis of leukemia, greater optimism, and illness impact were associated with higher levels of benefit finding in survivors. |

| Ozono et al49 | Japan | 9 | To identify types of family clusters with cancer survivors, and assess the relationships between psychological distress (anxiety, depression, and PTSD) and family functioning | 88 | 16.2 (2.2) [12-20 years] | 5.4 (3.8) years | >1 year | Brain tumors excluded, ALL (52%), other leukemia (16%), malignant lymphoma (10%), infant neuroblastoma (12%), other solid tumors (10%) | Adolescent survivors from conflictive families had higher levels of PTSD symptomatology, depression, and anxiety. Survivors who experienced a relapse had scored higher on PTSS. |

| Pelcovitz et al50 | United States | 7 | To examine PTSD and family functioning in survivors and their mother and compare it to physically abused adolescents and healthy controls | 23 | 17.6 (3.1) [15-19 years] | 10.5 [2-18 years] | 3.3 [0-11 years] | Leukemia (52%), lymphoma (30%), carcinoma (13%), Wilms tumor (4%) | 34.8% of survivors met lifetime, and 17.4% met current PTSD criteria, rates higher than in abused and healthy controls. Survivors reporting PTSD described their families as more chaotic, and 83% had mothers with PTSD. |

| Pendley et al51 | United States | 6 | To describe psychosocial (social anxiety) and body image difficulties in adolescent survivors and compare them to healthy controls | 21 | 11-21 years | 12.2 (2.69) years | 17 (8.65) months | Leukemia (38.1%), lymphoma (42.9%), other solid tumors (19%) | Survivors did not report higher social anxiety than peers. Those who were off treatment for more than a year reported lower self-worth, more social anxiety, and more negative body image perceptions. |

| Robinson et al52 | United States | 7 | To assess PTSS and PTSD in young adult survivors of childhood cancer and compare them to healthy peers | 56 | 18.6 (0.8) years | 8-15 years | >1 year | Brain tumors excluded, lymphoma (39%), leukemia (37%), solid tumors (24%) | 3% of survivors met current or past PTSD criteria compared with 6% of comparison. Late effects were associated with more PTSD symptomatology. Only 31% of survivors described cancer as a traumatic event. |

| Servitzoglou et al53 | Greece | 8 | To describe psychological well-being (of AYA cancer survivors and compare them to healthy peers | 45 | 19.8 [15-29 years, analyses split for adolescents | 8.8 [1-15 years] | >2 years | Leukemia (49.5%), sarcoma (17.5%), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (12.6%), Hodgkin disease (8.7%), Wilms tumor (2.9%), other (6.9%) | Survivors reported higher state and trait anxiety than controls. Survivors with younger age at diagnosis had higher levels of anxiety. |

| Turner-Sack et al54 | Canada | 6 | To examine survivors' psychological distress (via BSI) and assess demographic, disease-variables, and coping strategies in relationship to PTG | 31 | 15.7 (2.25) years | 7.45 (4.75) [2-17 years] | 6.5 (2.7) [2-10 years] | Brain tumors excluded; ALL (58%), Hodgkin lymphoma (13%), AML (10%), other (19%) | Younger age at diagnosis and less avoidant coping predicted lower psychological distress. Distress went down with time passed since diagnosis. |

| Yallop et al55 | New Zealand | 8 | To describe psychological well-being (depression and anxiety) of adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and compare it to healthy controls | 107 | 15.3 [12-18 years] | 5.6 [0-15 years] | >2 years | Leukemia and lymphoma (49%), CNS (13%), other (38%) | 6% and 7% of survivors reported depression and anxiety, respectively. Survivors were sig. less likely to report abnormal psychological functioning, however, those with CNS tumors, older individuals, older at the time of diagnosis and from lower SES reported more psychosocial difficulties. |

- a N = Survivor sample size.

- Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; AYA, adolescent and young adult; CNS, central nervous system; PTG, posttraumatic growth; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; PTSS, posttraumatic stress symptoms; QOL, quality of life; SES, socioeconomic status.

Based on our quality checklist, eight (42%) studies met criteria for high quality, and only one (5%) study missed more than three quality indicators.46 Majority of the studies were penalized due to lack of random sampling and representativeness of the population studied.

5.1 Prevalence of psychiatric disorders

Rates of PTSD among adolescent cancer survivors ranged from none43 to 35%.50 Additionally, Brown et al43 reported that 36% (n = 18) of survivors self-endorsed subthreshold PTSD symptomatology, a significantly higher proportion than healthy controls (d = 0.6). Studies that utilized clinical interviews for the assessment of PTSD also found large variability in PTSD rates. Robinson et al52 reported 3% of survivors meeting current or past PTSD criteria, with survivors experiencing lower levels of PTSD symptomatology (d = 0.36) than a control group. Alderfer et al40 reported 8%, and Erickson et al45 reported 13.8% of survivors meeting full-PTSD criteria. Kazak et al,19 who excluded any survivors who experienced relapse found that 4.7% of survivors met the criteria for current PTSD diagnosis, and 8% had PTSD sometime since the initial diagnosis. Based on the survivors' responses on Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID), arousal symptoms were predominant with 41.3% of adolescent survivors endorsing enough arousal symptoms to fulfill criteria for PTSD cluster D.19 In a sample evaluated by Pelcovitz et al,50 17.4% of adolescent survivors met current, and 34.8% met lifetime criteria for PTSD. The PTSD rates were higher in survivors than in abused children and healthy controls, though the study was statistically underpowered to detect significance.50 Overall, a substantial subset of adolescent cancer survivors considers their cancer experience traumatic and appears to be at risk for developing PTSD.

Depression and anxiety rates were modest in our sample, up to 8.5%42 and 8%,47 respectively, when measured using self-reported questionnaires. In addition to 8.5% that scored in clinical levels of depression, Bitsko et al42 reported that an additional 8.5% experienced mild depressive symptomatology and Fritz and Williams46 found an additional 12% of the sample that reached subthreshold levels of clinical depression.46

Case-control studies reported higher levels of depression and anxiety among adolescent cancer survivors than in control groups. In an online survey study, 6% and 7% of adolescent cancer survivors scored in clinical levels for depression and anxiety, respectively, with cancer survivors reporting significantly more depression compared with a population-based control (d = 1.06).55 Gianinazzi et al18 evaluated psychological functioning of adolescent survivors and compared it to that of siblings, population-based control, and functioning of psychotherapy patients prior to their engagement in therapy. Thirteen percent of survivors reported clinically significant distress based on the Global Severity Index (GSI). Adolescent survivors reported significantly more anxiety (d = 0.25) and more depression (d = 0.15) than control group. Survivors with higher GSI scores reported more anxiety than psychotherapy patients (d = 0.46).18

Two studies evaluated psychological outcomes of brain tumor survivors alone.44, 56 Both studies found large discrepancies between self-ratings and clinician or parent ratings. Carpentieri et al44 reported that 6.5% and 3.2% of adolescents self-reported at-risk levels of depression and anxiety, respectively, based on BASC-2, while parent and even teacher reports indicated higher levels of survivors' symptomatology. According to parental reports, 16% of brain tumor survivors experienced depressive symptomatology, and 12.5% experienced anxiety. Teachers reported higher anxiety among survivors than parents, with 19.4% of survivors having at-risk levels of anxiety and 9.7% experiencing at-risk levels of depressive symptomatology.44

Liptak et al (2012) similarly found large discrepancy between self-reported symptomatology and clinician ratings. Among adolescent brain survivors, 6% self-endorsed depression and 8% anxiety; however, 24% met criteria for depression and anxiety when evaluated by a trained clinician.56

5.2 Predictors of psychiatric disorders in adolescent cancer survivors

Studies in our review assessed a wide range of variables and their relationship to psychopathology. We identified several predictors of psychiatric disorders; some of these predictors are nonmodifiable (ie, gender), while others are modifiable (ie, coping styles).

5.2.1 Demographics

The majority of the studies did not include demographic variables in their analyses. While two studies did not find evidence that gender, race, and parental education were not associated with psychopathology in survivors,17, 52 Gianinazzi et al18 reported female gender to be a significant risk factor for greater psychological distress among adolescent survivors. Yallop et al55 reported that older age at the time of the study, older age at diagnosis, and lower socioeconomic status were positively correlated with psychosocial difficulties; however, none of the demographic variables were significantly related to clinical levels of anxiety or depression.

5.2.2 Coping styles

Four studies assessed coping mechanisms and adaptive styles among adolescent cancer survivors.41, 45, 53, 54 Survivors employed maladaptive coping strategies more frequently than healthy peers. When faced with challenges, they relied more on wishful thinking and avoidance and distancing strategies.41, 53 In another sample, survivors who were rated as nonrepressors endorsed more PTSD symptoms than repressors and reported lower quality of life.45

Contrary to the authors' prediction, Turner-Sack et al54 found that less avoidant coping (denial, behavioral disengagement, and substance use) was associated with lower levels of distress in survivors, a finding that the authors attributed to low statistical power and a small sample size.

5.2.3 Cognitive vulnerabilities

In a sample of Greek adolescents, the majority of survivors perceived their future with optimism; however, survivors were less likely to report long-term plans than healthy controls and reported significantly more worries about health-related issues.53 Fritz and Williams46 who found low levels of depressive symptomatology in majority of the sample, also found that over 50% of adolescents expressed concern about their bodies, and 26% of them were affected with hypochondria. In yet another sample, greater levels of optimism among survivors were associated with more better psychological adaptation and positive outlook48; however, none of these studies explored how cognitive constructs related to varying degrees of psychopathology in young survivors.

Bitsko et al42 found that happiness and one's thinking about the past were stronger predictors of depression and quality of life in survivors than gender or treatment intensity, suggesting those areas could be targeted in interventions. Additionally, lower perceived parental support and lower levels of social desirability were associated with more anxiety and PTSD symptoms, respectively.18, 50

5.2.4 Late effects and treatment severity

Many survivors experience illness late effects that result from cancer treatment. Higher treatment severity is often associated with higher number of late effects, which can be physical, somatic, or psychological. Cousino et al17 assessed the relationships between brain tumor survivors' late effects, illness-specific family burden, and psychosocial outcomes. Parental reports indicated that 11% of survivors exhibited clinically significant internalizing problems and that higher number of late effects predicted illness-specific family burden, which in turn predicted child's internalizing symptoms.17 We found that higher number and severity of cancer late effects, as well as occurrence of illness relapse was also correlated with greater overall psychological distress, and more PTSD,17, 18, 49, 50 as well as lower self-esteem and greater difficulties in social relationships among adolescent cancer survivors.53

Though some studies in our review observed decreasing levels of psychological distress as more time elapsed since initial diagnosis,53, 54 Pendley et al51 found that survivors who were off-treatment for at least a year reported significantly lower self-worth (d = 1.1), more social anxiety (d = 1.11), and more negative body image (d = 0.88) compared with survivors within the first year since treatment completion.51 The authors suggested that this may be due to the slowing down of positive changes and late effects becoming more apparent after the first year of remission.51

5.2.5 Tumor type

All but two studies recruited survivors of various types and stages of childhood cancer, which makes differences between the impact of different types of diagnoses hard to detect. Brain tumor cases face more psychosocial difficulties particularly in the area of peer relationships and self-concept.47, 56 A discrepancy was observed between the self-ratings and clinician ratings; clinicians reported higher levels of social difficulties than brain tumor survivors, who either did not report any problems or did not perceive the nature of their social relationship as troublesome or developmentally inappropriate.56 Moreover, when evaluated by teachers and parents, brain tumor survivors exhibited more problems with attention and leadership in school settings.44

In a sample that included all types of diagnoses, Michel et al48 found that a diagnosis of leukemia predicted more “benefit finding” than a diagnosis of other tumors. Benefit finding implies a more positive disposition and has been associated with higher levels of optimism and self-esteem and lower levels of trait anxiety.57 Ozono et al,49 in a sample that exuded brain tumor cases, reported that the type of cancer diagnosis did not appear to be related to the levels of anxiety or depression among the adolescent survivors.

5.2.6 Family environment

Family environment and parental mental health are often implicated in a child's adaptation to chronic illness and the life after it. Alderfer et al40 assessed family functioning via Family Assessment Device (FAD) in areas of problem solving, communication, roles, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, behavioral control, and general functioning. Cancer survivors who reported PTSD had a fivefold increased chance to come from poorly functioning families compared with healthy controls. Seventy-five percent of survivors meeting PTSD criteria came from families with poor family functioning, particularly in the areas of problem solving, affective responsiveness, and affective involvement.40

Ozono et al49 evaluated family functioning with the Family Relationship Index (FRI), which assesses the interpersonal relationships and organizational structure within a family unit. Additionally, the authors measured parental mental health and applied a clustering method to identify three different types of family environments that formed as a result of facing childhood cancer: supportive, intermediate, and conflictive type. These types varied on three main dimensions: family cohesiveness, expressiveness, and conflict. Thirteen percent of families fell within the conflictive type, marked by highest level of family conflict and lowest levels of family cohesiveness and expressiveness. Survivors from families that fell within the conflictive type reported the highest levels of clinically significant PTSD symptomatology, as well as depression and anxiety. Moreover, parents of cancer survivors in the conflictive type also reported highest rates of psychopathology, while adolescent survivors who came from the supportive families had the lowest levels of depression and anxiety symptoms.49

In addition to poorly functioning family environments, there is evidence for a strong positive association between mother's PTSD and child's PTSD symptoms.19, 42, 50 The adolescent survivors who met the PTSD criteria reported their families to be more chaotic, and results show that 83% of them had mothers who met full PTSD criteria.50 Another study reported close to 30% of mothers and 12% of fathers of adolescent cancer survivors meeting full PTSD criteria,19 while Brown et al43 reported 25% of mothers of survivors meeting PTSD compared with 7% of mothers in the control group. Kazak et al19 found that 99% of the families that participated in the study had at least one member re-experiencing cancer-related events, suggesting that childhood cancer profoundly impacts all family members.

Only one study compared survivors' outcomes to those of siblings' and found that survivors reported clinically significant psychological distress at a higher frequency.18

5.2.7 Peers

The relationship between psychological adaptation and cancer survivors' peer involvement and activities was directly evaluated by a single study in our review. Pendley et al51 recruited 21 adolescent survivors, and healthy controls matched in age, gender, and ethnicity in order to evaluate social anxiety, body image, peer activities, loneliness, self-perceptions, and school attendance. The authors report that adolescent survivors participated in significantly fewer peer activities compared with healthy controls (d = 0.94); however, survivors did not report significant differences in feelings of loneliness or social anxiety.51

6 DISCUSSION

Due to the continuing development of medical interventions, childhood cancer diagnoses are no longer synonymous with early death. Nevertheless, the illness and its treatment can be traumatic for everyone involved and can compromise psychosocial development and adaptation of a young survivor. It is important that researchers, medical workers, and clinicians understand the psychological profiles of adolescent cancer survivors and areas in which they might require most help and support. In our review, we were guided by two main research questions: (1) What is the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in adolescent cancer survivors? and (2) What are the predictors of psychiatric disorders in this population? We aimed to develop a better understanding of the nature of psychiatric disorders in adolescent survivors, and how to best address them. This systematic review can be informative for any professional working with young survivors by demonstrating the most common psychological difficulties and predispositions to mental health disorders in this population. Poor mental health in young people remains the leading cause of disability58; thus, routine assessment of psychological functioning, from intake through treatment completion and follow-up care, should become a norm in oncology settings.

Nineteen studies summarized in our review assessed PTSD, depression, and anxiety among adolescent cancer survivors. The rates of psychopathology showed large discrepancies between different samples, some reporting rates higher than population-established norms,17, 18, 42, 45, 56 some similar to population levels,47, 53 and others lower.43, 50, 52 Nevertheless, our results suggest that a significant proportion of adolescent survivors are at risk for developing clinically significant symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, and depression.

Several studies in our review reported subthreshold levels of psychopathology.19, 43, 50, 55 These individuals who do not meet full criteria for any given disorder should be equally attended to in order to prevent worsening of symptoms. There is growing evidence showing that subthreshold levels of psychopathology are associated with an array of adverse outcomes: suicidal ideation, higher comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders, and overall higher social and functional impairment.59-63 Young cancer patients should be regularly assessed from intake through treatment completion for their symptoms, even when they do not initially meet any psychiatric disorder criteria. Early intervention strategies contribute to better long-term adaptation and coping.64

In addition to psychiatric disorders, two studies in our review assessed somatization as an independent construct.18, 44 The small number of studies that report somatization reflects cancer survivorship literature at large. Somatic symptoms are difficult to differentiate from the illness side effects, late effects, or mood symptomatology; however, findings in adult cancer patients show that somatization may be entirely independent from depression and anxiety.65 Some patients exhibit significant somatic symptoms even upon full remission of cancer and report higher PTSD and distress levels.66 Somatization can affect pain perception, treatment outcomes, and quality of life.15 Research suggests that fatigue, one of the most common complaints in survivors, might have a more significant negative impact on one's well-being than nausea, depression, or pain.67 Managing somatic symptoms in adolescent survivors may help in reducing psychological distress and negative or excessive help-seeking behaviors.

Our data synthesis identified several predictors for psychiatric disorders in adolescent cancer survivors. Survivors at a higher risk for PTSD employed more repressive coping mechanisms,45 reported lower levels of social desirability,43 came from families with poorer emotional functioning, lower support, and more conflict,40, 49 experienced a relapse,49 or reported more illness late effects.17, 18, 50 Consistent with the broader literature on the relationship between parental and child mental health,68 adolescent cancer survivors reporting PTSD were also more likely to have mothers with clinically elevated PTSD scores.19, 42 Higher levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms were also associated with poorer overall family functioning,49 female gender,18 higher number of late effects,17, 18 lower perceived parental support,18 less time passed since diagnosis,44 older age at assessment and at diagnosis, and lower socioeconomic status.55

In line with the existing literature in adult cancer populations,69, 70 coping mechanisms such as wishful thinking and avoidance were associated with greater anxiety,41 while higher levels of happiness and less thinking about one's past predicted lower depression.42 Social anxiety was associated with poorer body image and larger illness impact and was significantly higher in adolescent survivors who had been off-treatment for at least a year.51

6.1 Limitations and future directions

Our review presents with some limitations and methodological issues, which also pertain to the field of psycho-oncology at large. The number of studies considering psychological adaptation to cancer in adolescence is scarce. The paucity of research, small sample sizes, grouping of all cancer types, and grouping of adolescents with either children or young adults may partially be explained by overall low number of cancer cases in this particular age range.1 We have tried to address this issue by selecting a wide age range (10-23 years); however, the variability is still very large. Additionally, we were interested in the survivorship period after the first 12 months of treatment completion. This is the time when the rapid positive changes such as hair growth, and increases in energy slow down, and when patients are confronted with novel challenges of being in remission.41 Unfortunately, the range of years since treatment completion also varied greatly in our sample, thus limiting our ability to suggest at what point in the survivorship adolescent survivors might be experiencing most clinically significant psychological symptoms. Future studies should carefully consider the age of participants, as well as the age at diagnosis, and conduct separate analyses for adolescent cancer survivors whenever possible.

Secondly, we mostly relied on self-report measures of psychiatric disorders in adolescent cancer survivors. Although some evidence suggests that these are more reliable than parental ratings in this specific population of adolescents,71 future work should aim to confirm this finding and further explore the discrepancies, particularly in patients with diagnosis of brain tumors.

Moreover, some studies report participation rates as low as 30%.42 Some authors noted that participants declined due to unwillingness to talk about their illness or reliving past events,19, 40 which might be, in cases like PTSD, the exact construct that the studies are trying to measure. Additionally, most studies lacked a control group, and an array of questionnaires not adapted to populations with cancer has been utilized.

7 CONCLUSIONS AND CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

Adolescents cancer survivors are a unique and understudied group in oncological research, with lowest participation rates in clinical trials, and slowest progress in improvement of care.2, 68 Working with adolescents in medical settings requires establishing adolescent-friendly ways of discussing their concerns, expressing their needs following their illness, and reflecting back on it. A one-size-fits-all approach is not suitable for this population. Young cancer survivors should be monitored for signs of psychological distress and offered follow-up consultations even in case of subclinical presentations of psychiatric disorders. In particular, those adolescents that present at the clinic with more risk factors such as poorer family functioning or lower levels of optimism should be offered further psychological evaluations and interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This article is part of Ms Kosir's doctoral project. Her work is supported by Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Fund and Ad Futura Scholarship from the Slovenian Government. ESRC and Ad Futura had no role in the design, analysis, or preparation of this manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Conceptualization, U.K., M.W., J.W., L.B.; Methodology, U.K., M.W., J.W., L.B.; Investigation, U.K., M.W., L.B.; Formal Analysis, U.K., M.W., L.B.; Writing -Original Draft, U.K., M.W., J.W., L.B.; Writing - Review & Editing, U.K., M.W., J.W., L.B.; Visualization, U.K., M.W., J.W., L.B.; Supervision, J.W., L.B.