Primary pancreatic peripheral T-cell lymphoma-not otherwise specified mimicking acute pancreatitis: A case report and review of literature

Rahem Rahmati is cofirst author.

Key Clinical Message

Primary pancreatic lymphoma is a rare disease that can mimic acute pancreatitis. Since the prognosis and approaches differ, clinicians should differentiate it from other pancreatic diseases, especially autoimmune pancreatitis and adenocarcinoma.

1 INTRODUCTION

Lymphoma is divided into Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL). Primary pancreatic lymphomas (PPL) constitute fewer than 2% (0.16–4.9%) of all lymphomas, 0.1% of malignant lymphomas, and 0.5% of pancreatic tumors. The vast majority of PPL are extranodal NHL.1-3

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCL) are a rare and heterogeneous group of lymphoid malignancies that comprise approximately 15%–20% of all NHL.4, 5 About 30%–50% of PTCL patients are not further identifiable using existing immunophenotypic and molecular markers and are thus classified as PTCL-not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS).6 The most frequently diagnosed and highly aggressive subgroup of PTCL is PTCL-NOS.7 The least common presentation of PTCL-NOS is extranodal, among which the most commonly reported sites are the spleen (24%), liver (17%), skin (16%), lungs (8%), and the subcutaneous tissue (6%).5

Primary pancreatic T-cell lymphoma is extremely rare and demonstrates a worse prognosis compared to the B-cell ones, with 5-year relative survival estimates of 45.4% and 68.8%, respectively.8 Pancreatic lymphoma symptoms, such as pancreatitis, are often heterogeneous and can be mistaken for other pancreatic diseases like adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors, and chronic pancreatitis. As the management of these conditions differs from the others, it is necessary to differentiate between them. Considering the rarity of PTCL, additional data on the presentation of the disease may guide through a proper diagnosis.1, 9 To the best of our knowledge, the present case report is the first case of primary pancreatic PTCL-NOS mimicking acute pancreatitis.

2 CASE PRESENTATION

A 35-year-old Caucasian female was admitted to the hospital with a 1-day intermittent nonpositional epigastric and left upper quadrant abdominal pain without radiation and progressive jaundice. She denied having nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, or urine color changes. She was hospitalized 2 weeks earlier due to acute pancreatitis. During the previous hospitalization, the patient was diagnosed with acute pancreatitis based on lipase 386 U/L (normal range, 0–70 U/L) and a sonographic confirmation. A week later, she was discharged without complications with lipase 200 U/L, amylase 88 U/L (normal range, 0–90 U/L), and a normal magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). She also had glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency. She had no relevant habitual or family history. Vital signs were stable, but we found tendered epigastric and left upper quadrant area and a soft abdomen with positive Murphy's sign in the physical examination.

3 METHODS

Laboratory evaluation indicated a normal complete blood count, urea nitrogen, creatinine, albumin, amylase, the international normalized ratio (INR), and partial thromboplastin time (PTT). The result of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) serology was also negative. Serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were 375 and 318 U/L, respectively (normal range for both <40). Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and lipase were also elevated with the level of 604 U/L (normal <105) and 274 U/L (normal <160), respectively.

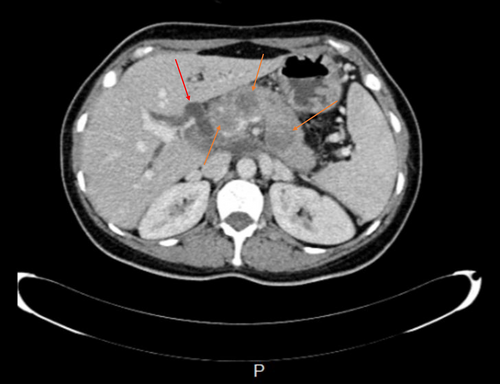

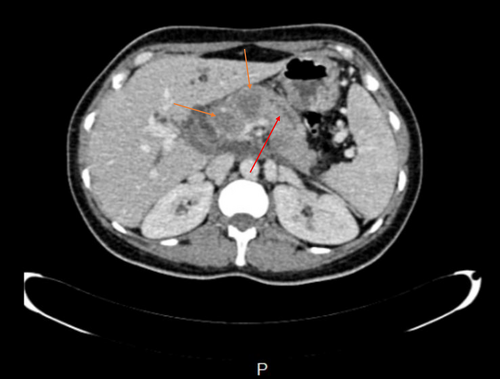

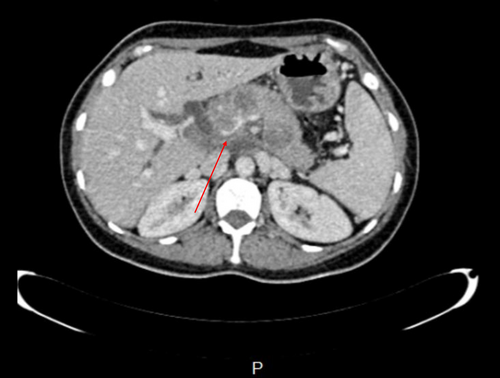

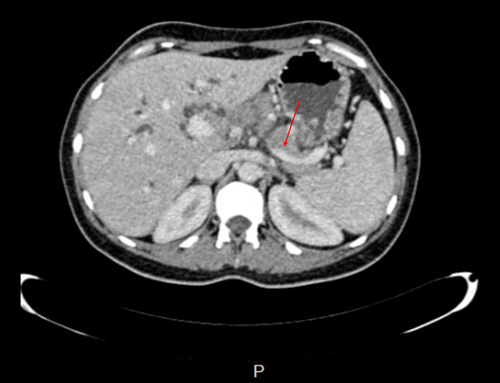

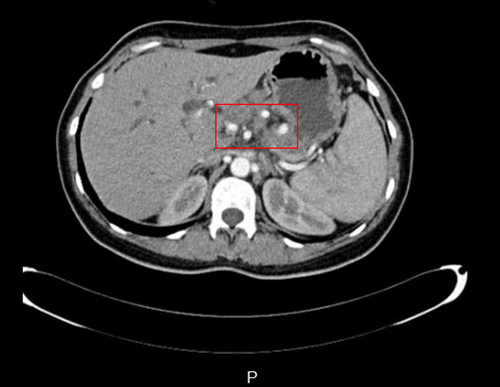

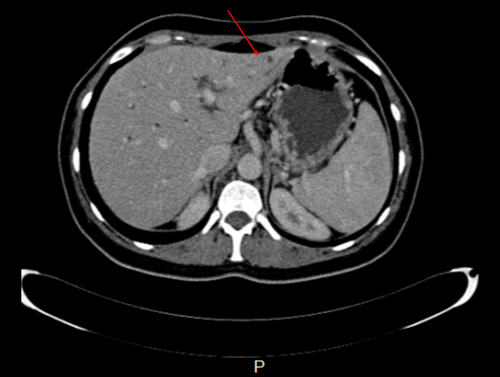

Ensuing abdominal ultrasonography revealed dilated intrahepatic bile ducts, elongated gallbladder with sludge, prominent pancreas, heterogenic hypoechoic areas with faint peripheral flow in the head, and no vascular flow in the neck and tail of the pancreas. Also, oval-shaped lymph nodes with a maximum short axis diameter of 10 mm were seen in the porta hepatitis and peripancreatic area. As recurrent pancreatitis was suspected based on abdominal pain, raised lipase level, and sonographic features, we started pancreatitis supportive therapy as suggested by the guidelines. However, her condition did not improve after 2 days. In this regard, we suspected other possible diagnoses, such as autoimmune diseases, granulomatosis disorder, and malignancies. Therefore, a multidetector computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous contrast was ordered (Figures 1-6).

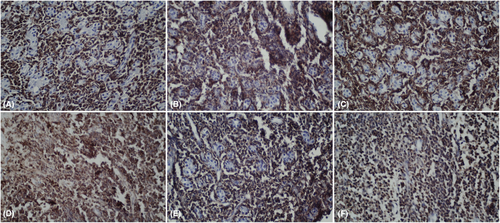

CT scan revealed hypodense areas at the pancreatic head, neck, and body measuring 30*36, 21*25, and 29*24 mm, respectively. Accordingly, the endosonographic biopsy was taken from the hypodense lesions. Pathologic evaluation revealed stage II T-cell lymphoma in the pancreas, based on which T-cell lymphoma was brought up as the culprit for pancreatitis. Immunohistochemical staining revealed that the cells were positive for CD3, CD4, CD8, CD10, CD45, PD-1, GATA3, and Ki67 (60% of tumoral cells) but were negative for CD20, CD30, CD34, TdT, and ALK (Figure 7). Based on the pathological and immunohistochemical evaluations of another expert pathologist, the diagnosis of PTCL-NOS was confirmed for the patient.

These results also confirmed the diagnosis of PPL. Additional assessments with Positron emission tomography (PET)-CT and MRI of the brain rejected CNS invasion by the tumor cells. Therefore, applying guidelines, the patient received adjuvant chemotherapy with six regular cycles of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin, and prednisone) regimen.

4 CONCLUSION AND RESULTS

No significant changes occurred in the three masses in the monthly clinical and imaging follow-ups. During the treatment period, she experienced a terrible constant headache. A CT scan was subsequently ordered, confirming the tumoral involvement of the CNS. Since morphine alleviated her headache, she refused any other medical or surgical treatment. Her last visit happened around 1 year following the diagnosis, and she was lost to follow-up after that visit.

5 DISCUSSION

Acute pancreatitis may be caused by a myriad of factors. The incidence of pancreatitis is expected to increase during the next generation due to the rising rates of many risk factors.10 However, it is rare to see acute pancreatitis in the context of NHL11-13 of the pancreas, which only affects 0.2% to 2% of NHL cases, with or without peripancreatic lymph node involvement.11, 14 Male predominance has been documented for PPL cases in several studies with an average age of 55 or the seventh decade of life.15-17 Contrastly, our patient was a female in her mid-thirties.

Based on the high expression of either GATA3 or TBX21, there are two main molecular subgroups of PTCL-NOS.18 In about one-third of PTCL-NOS, elevated expression of GATA3 and its target genes defines a subtype. The transcription factor, GATA3, controls the expression of interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, and IL-13 throughout T-helper 2 cell development. High expression of TBX21 and target genes characterize the other subtype of PTCL-NOS, accounting for nearly 50% of the total. Interferon-gamma and granzyme B expression are regulated by TBX21, making it the primary regulator of T-helper 1 and cytotoxic T-cell development.18 Immunohistochemistry identification of the PTCL-GATA3 subtype and a high International Prognostic Index (IPI) score were independently linked with poor overall survival in a multivariate analysis.19

Among very few reported pancreatic T-cell lymphomas, our patient was the first case of primary PTCL-NOS in the head, neck, and body of her pancreas. By contrast, the most common subtype of PPL, large diffuse B-cells, is mainly found in the head of the pancreas.1, 14-17, 20 According to the nine case reports with 10 cases and efficient details on pancreatic T-cell lymphomas (Table 1), the median age of the patients is 56.7 (nine cases, min: 28-max: 82), and males predominate (five cases, 55%). Only one of the studies disclosed the patient's prior gastric cancer. Most cases have the involvement of the head of the pancreas (nine cases, 90%) and have abdominal pain as the most prevalent symptom (eight cases, 88%). The survival of the patients ranges from zero to 31 months, and just one study reported a case with metastases.

| Author | Year | Country | Age | Sex | Diagnosis | CT findings | Survival rate | Location | Size | Treatment | Symptoms | Laboratory data [LDH/ CA 19–9/ CEA] | Medical history | Metastases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satake et al.38 | 1991 | Japan | 52 | M | Large cleaved-cell (intermediate grade) NHL | Diffuse enlargement of the entire Pancreas with periaortic lymph node swelling | DOD 6 months later | Entire | 70 × 80 mm | Chemotherapy | Abdominal pain + pruritus + diarrhea + weight loss + abdominal mass | CA 19–9 was elevated [143,7 Flml, normal of less than 37 p/ml], with normal CEA | Neg | NA |

| Nishimura et al.31 | 2001 | Japan | 52 | M | Peripheral T-cell | NA | DOD 8 months later | Entire | NA | Chemotherapy | Abdominal pain | NA | NA | NA |

| Nishimura et al.31 | 2001 | Japan | 46 | F | Anaplastic large T-cell | NA | No evidence of disease 4 months later | Head | 40 mm | Surgery and chemotherapy | Abdominal pain | NA | Gastric cancer | NA |

| Matsubayashi et al.39 | 2002 | Japan | 82 | M | NHL, diffuse, of mixed medium-to-large cell type | A weakly enhanced, diffusely swollen pancreas | DOD 2 months later | Entire | NA | Conservative therapy | Abdominal fullness + loss of appetite | Slightly high levels of LDH, with a normal range of CA 19–9 and CEA | Neg | Gastric subserosa and lymph nodes adjacent to the pancreas, aorta, spleen, and biliary system |

| Galarreta et al.40 | 2012 | Peru | 28 | F | T cell NHL, CD3+ CD20- | A diffuse heterogeneous mass along with a mildly dilated pancreatic duct and dilated intra and extra-hepatic bile ducts | DOD 0 months | Head | NA | Postmortem diagnosis | Fatal acute cholangitis+ insidious weight loss+ obstructive jaundice | NA | NA | NA |

| Liu et al.41 | 2013 | China | 62 | M | Extra-nodal NK/T-cell | Mild dilation of the main pancreatic duct |

No evidence of disease. Expired 6 months after surgery |

Head | 44 mm | Surgery | Upper abdominal pain + weight loss | Normal levels of LDH and CA 19–9 [22.9 IU/L] | Neg | Neg |

| Demirel et al.42 | 2018 | Turkey | 47 | F | PTCL-NOS | 18-FDG PET/CT revealed a focal increase of uptake of FDG in the corpus of the pancreas, while no distinctive lesion was detectable on unenhanced CT. A pancreatic lesion had not been shown by the diagnostic enhanced CT before and during chemotherapy | NA | Body | 16 mm | After receiving chemotherapy, consolidation with autologous stem cell transplantation | Abdominal pain+ nausea+ left lower abdominal tenderness | NA | NA | NA |

| Chon et al.43 | 2020 | Korea | 80 | F | Extra-nodal NK/T-cell | Diffuse enlargement of the pancreas with peripancreatic haziness, homogenous mass with central necrosis in the pancreatic head | DOD 32 days later | Head | 55 mm | One cycle of cisplatin-based concurrent chemoradiotherapy | Hypertension+ epigastric pain for 3 days | Elevated levels of CA 19–9 [45 U/mL] and CEA [6.82 ng/mL] | NA | NA |

| Facchinelli et al.44 | 2020 | Italy | NA | NA | PTCL | NA | DOD 31 months later | Mostly head | The mean size of 81 mm | Neg | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Nadaleto et al.45 | 2021 | Brazil | 62 | M | Non-Hodgkin matures T-cell | A large tumor close to the superior and inferior vena cava involving the gastroduodenal artery | No evidence of disease after 8 months | Head | 73 mm | Surgery and Chemotherapy | Cholestatic symptoms for 40 days+ progressive epigastric pain+ itchy skin+ gynecomastia+ weight loss of about 8 kg | Elevated CA 19–9 [>10.000 U/mL] and CEA [6.5 ng/m] | Neg | NA |

- Abbreviations: 18-FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose F 18; CA-19-9, carbohydrate antigen; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; DOD, died of disease; F, female; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; M, male; N/K, natural killer; NA, not applicable; Neg, Negative; NHL, Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; PET/CT, Positron emission tomography/Computed tomography; PTCL-NOS, Peripheral T-cell lymphoma-not otherwise specified.

PPL is difficult to consider in the differential diagnosis because of the nonspecific presentations of pancreatic disorders, including abdominal pain.15, 16, 21-23 It normally takes 4–5 weeks to receive a diagnosis from the first symptom onset.15 Abdominal pain, jaundice, and acute pancreatitis were also our patient's symptoms, with prevalence rates of 83%, 37%, and 12% in the literature, respectively.16, 17 The patient had no other NHL symptoms, such as fever, chills, or night sweats, found in about 2% of PPL patients.20

Due to the differences in the treatment methods and the prognosis between PPL, autoimmune pancreatitis, and more common adenocarcinoma, their differentiation seems essential. Though there is a similarity between the symptoms and the imaging findings, some clues exist to differentiate them.1, 24 Serological alterations, histological characteristics, such as lymphocyte infiltration and pancreatic interstitial fibrosis, and imaging findings, including pancreatic enlargement and irregular constriction of the major pancreatic duct, are all linked with autoimmune pancreatitis.25 However, PPL suspicion is based on a CT scan showing pancreatic bulky, homogeneous, and poor enhancing lesions as opposed to adenocarcinoma.1, 15, 26, 27 The vascular encasement is prevalent in PPL, although ductal adenocarcinoma is more likely if the vessel walls drastically change with early infiltration, erosion, stenosis, and tumoral thrombosis.28 In PPL, enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes are also frequent, and fat stranding is constant,28 as in our patient with a short axis diameter of 10 mm. Although concurrent dilatation of the common bile duct and pancreatic duct is prevalent in pancreatic head adenocarcinoma, it was identified in this case and under half of the PPL patients in a study conducted by Boninsegna et al.28 involving three pancreatic disease referral centers. Moreover, biliary, pancreatic duct or venous obstruction is uncommon in PPL,29 while we found collapsed splenic vein and portal vein thrombosis in our patient.

Dawson et al.30 suggested five criteria for diagnosing PPL, including the absence of peripheral lymphadenopathy, lack of involvement of mediastinal lymph node, normal peripheral white blood cell count, mass localized in the whole, or just a segment of the pancreas, with involvement of lymph nodes limited to the pancreas itself, and lack of involvement of liver or spleen, all of which were met in the current case except liver involvement.14 This pancreatic lesion could be found in the entire pancreas, as in our patient, or isolated or multiple in only a section of the pancreas.27

Despite the importance of imaging, histopathology and cytology are required for the confirmation and subclassification of lymphoma (Table 1).26 Based on 19 cases of PPL analysis in Japan, B-cell lymphoma patients were meaningfully older than T-cell ones. However, the T-cell phenotype had a longer duration of being symptomatic.31 Five-year and overall survival rates for individuals with PTCL-NOS are around 20%–30%, and figuring out the best treatment is challenging. When it comes to treating PTCL-NOS, chemotherapy is still the gold standard. The complete response rate with conventional anthracycline-based treatment is 40%–60%, and the overall survival rate is 30%–40%.6 When combined with autologous stem cell transplantation, the chemotherapy regimen CHOEP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, and etoposide) may be the most effective treatment, curing about half of patients. However, the best method for treating PTCL-NOS has not been established yet.32

On the contrary, patients with PPL have a 5-year survival rate of 26%–66%1 and a cure rate of 30% when treated with chemotherapy or surgery.26 In most cases, chemotherapy with or without rituximab is the mainstay of the treatment.16 Rituximab is indicated to treat almost all CD20+ NHL33; hence, it had no indication regarding her negative CD20. Unlike epithelial malignancies, patients with lymphoma benefit from chemotherapy rather than surgery, which may worsen morbidity.3, 28 However, our patient's prognosis had not changed since the chemotherapy started. Besides, she revealed a CNS involvement. The recurrence rate of extranodal lymphomas is as high as 23.52%–34.21% in the earlier reported cases.16

Only a few studies have been published that specifically investigate the likelihood of CNS disease and relapse in PTCL.34 The CNS-International Prognostic Index (CNS-IPI) does not consider primary lymphoma of the pancreas at elevated risk of CNS involvement.35 Although PTCL affects the CNS in only around 4%–6% of patients,34 Facchinelli et al.16 reported one in every five of their PPL patients showing CNS relapse or advancement. The Swedish Lymphoma Registry study identified GI tract involvement as a significant risk factor for CNS relapse in PTCL.36 The literature discusses the potential usefulness of CSF cytology and circulating tumor DNA in predicting CNS involvement or recurrence alongside MRI or whole-body PET-CT, particularly for B-cell lymphoma.37 Biological risk factors, such as MYC translocation along with a BCL2 and/or BCL6 translocation or MYD88L265P, CD79, PIM1, and ETV6 mutations, are also used to identify individuals at high risk for CNS involvement.37

In conclusion, given the notable CNS involvement of our patient, as well as the rising prevalence of acute pancreatitis and its rare etiology of malignancy, particularly PPL and PTCL-NOS, the findings of this case could assist physicians in earlier diagnosis and proper management, as specific treatment is required when PPL is the etiology of pancreatitis. However, our report is subject to certain limitations. The details of the patient's treatment and the images of the brain CT scan were missed since it was done in another county, though the patient's oncologist confirmed its report. She was also lost to follow-up, and her outcome remained unknown.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Fatemeh Zarimeidani: Data curation; project administration; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Rahem Rahmati: Data curation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Elahe Meftah: Writing – review and editing. Maryam Soheilipour: Conceptualization; investigation; supervision; validation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Dr. Yaser Salehinajafabadi, Dr. Pardis Nematollahi, and Dr. Maryam Anjomshoa for their support.

FUNDING INFORMATION

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The authors declare that human ethics approval was not needed for this study.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.