Lutembacher's Syndrome in a 45-Year-Old Female From Ambo University Hospital of Ethiopia: A Case Report and literature Review

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Lutembacher's syndrome is characterized by an atrial septal defect (ASD) combined with mitral stenosis (MS) of variable severity, both of which can be either congenital or acquired with or without the presence of varying grades of mitral regurgitation. Appropriate diagnosis with the optimal therapy depends on knowing the syndrome. Furthermore, optimal medical therapy with or without surgical closure of the atrial septal defect is the standard of care for better patient outcomes.

1 Introduction

Though mitral valve lesions that cause heart failure and other consequences are common, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa where rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is prevalent, combinations of mitral stenosis (MS) with or without regurgitation in patients with atrial septal defect (ASD) are rare. We present a Lutembacher's syndrome (LS) in a 45-year-old female, who had been complaining of progressive worsening of shortness of breath over 1 year, along with orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, bilateral leg swelling, and a dry cough, that was confirmed after transthoracic echocardiography showing mild MS with a large ostium secundum ASD measuring 18 mm with a left-to-right shunt, associated with severe mitral regurgitation (MR), biatrial enlargement and severe tricuspid regurgitation, with severe pulmonary hypertension. Symptomatic improvement was attained with conservative medical management, with subsequent plan for possible surgical intervention.

This case presents a detailed clinical summary, supported by a review of similar reports from Africa, emphasizing the potential occurrence of LS in regions like sub-Saharan Africa, where RHD is prevalent. It underscores the importance of maintaining a high level of suspicion before the syndrome progresses to advanced stages.

2 Case Presentation

A 45-year-old black Ethiopian woman presented on May 21, 2024, with a 1-year history of progressive shortness of breath which occurred with significant exertion, and then worsening even with mild activities; that later started to occur at rest for the last 2 months, associated with dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, bilateral leg swelling, and palpitations. For 2 weeks, she complained of a productive intermittent cough which worsens during the supine position and improves in sitting. Associated with the cough, she complained of vague right-sided chest pain that also worsens with deep breathing and low-grade intermittent fever. She also reported reddish urine with pain during urination, with increased urine frequency than usual of 2 weeks duration. However, she did not have a history of syncope, near-drowning, skin rash, jaundice, dizziness, chills, fever, or hemoptysis. She is not a smoker or alcoholic. There was no documented history of acute rheumatic fever (ARF) in childhood. The patient denies any personal or family history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or sudden cardiac death. She is married with four children and has no history of psychiatric illness, drug allergies, or significant childhood illnesses.

Upon physical examination, the patient exhibited dyspnea at 45°. Her vital signs were as follows: Blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg, measured in the supine position; pulse rate was 74 beats per minute (and was regular); respiratory rate was 24 breaths per minute; temperature was 36.70°C; and oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. HEENT examination revealed normal hair distribution, no ear discharges, no tragus tenderness, and pink conjunctiva with muddy sclerae. On lymphoglandular examination: there is no visible anterior neck swelling, and there is also no identified lymphadenopathy in the accessible areas. Pulmonary examination revealed expiratory wheezing with some crackles in both lung fields. On cardiovascular examination, the jugular venous pressure was elevated at 4 cm above the sternal angle, while the point of maximal impulse was at the left fifth intercostal space along the left midclavicular line. There was a grade III pansystolic murmur best heard at the left lower sternal border radiating to the left axilla. On abdominal examination, there is a scaphoid abdomen which moves with respiration; hernia sites were free, the total vertical liver span measures 12 cm, and there were no signs of fluid collection identified; there was no identified organomegaly. Genitourinary and integumentary examinations were unremarkable. Bilateral pitting tibial edema was present in the lower extremities, but there was no clubbing or central or peripheral cyanosis. The patient was alert and oriented with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 15 out of 15.

3 Differential Diagnosis

High left atrial pressure caused by MS was considered to stretch open the patent foramen ovale (PFO), resulting in an ASD that allowed for a left-to-right shunt and additional exit for the left atrium (LA) in LS when you have mitral valve lesion with the presence of ASD. The ASD in this syndrome might be either congenital or acquired, so as MS. Though this cannot be confirmed because the patient presented with both at the same time, the appearance of both lesions on echocardiographic imaging is strongly suggestive of LS.

Typically, the right ventricle (RV) is more compliant than the left. As a result, when MS is present, blood flows to the right atrium (RA) via the ASD rather than backward flow into the pulmonary veins, avoiding pulmonary congestion, which is most likely why this patient presented late, though at the expense of progressive dilatation and, eventually, failure of the RV, as well as reduced blood flow to the left ventricle (LV), as in this case report. Eisenmenger syndrome or irreversible pulmonary vascular disease is extremely rare in the context of a big ASD and significant left atrial pressure caused by MS or MR, as was the case in this case study.

Survival to old age has also been observed in this syndrome, albeit the long-term natural history of ASD is influenced negatively by MS/MR, which increases the left-to-right shunt and predisposes to atrial fibrillation and right ventricular failure. MS, particularly when combined with MR, increases susceptibility to infective endocarditis, in contrast to the low frequency of infective endocarditis in uncomplicated ASD, as in our case.

4 Investigations and Management

Complete blood count revealed leukocytosis with left shift and mild eosinophilia; 14,000 WBC/mm3, polymorphonuclear cells of 84% (11,760), and 10.5% (1470 cells) of lymphocytes, 5.1% (714 cells) of eosinophils, 0.39% (56), hemoglobin of 14.1 g/dL, while the platelets were 275,000 platelets/mm3 (Table 1).

| Variables | Results | Normal ranges |

|---|---|---|

| WBC | 14,000/mm3 | 4–10 k/mm3 |

| Neutrophils in % | 84% | 50%–70% |

| Hgb | 14.1 g/dL | 13–16 g/dL |

| Platelet | 275,000/mm3 | 150–450 k/mm3 |

| MCV | 87 fl | 80–95 fl |

| Creatinine | 0.8 mg/dL | |

| ESR | 11 mm/h | 5–20 mm/h |

| Aso titer | Negative | |

| TSH | 4 | 0.35–5 |

| BNP | 350 pg/mL | < 100 pg/mL |

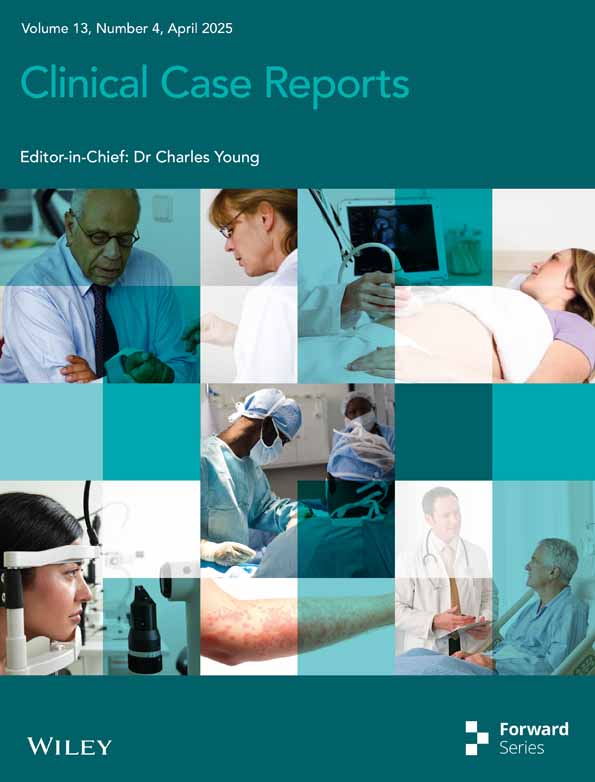

PA chest x-ray revealed borderline cardiomegaly, a sign of right atrial and right ventricular enlargement, with minimal right-side pleural effusion with futures of grade I pulmonary edema. Transthoracic echocardiography was performed using both 2D views and Doppler imaging, revealing several key findings. The mitral valve demonstrated calcified and restricted leaflets with diastolic doming (yellow arrow), and a mitral valve area of 1.32 cm2, consistent with mild MS. Additionally, a hypoplastic posterior mitral leaflet was noted (pink arrow), along with a dilated RV and a flattened interventricular septum. The left-sided chambers displayed a pansystolic eccentric jet of MR with a vena contracta greater than 0.7 cm, indicating severe MR, accompanied by significant left atrial dilation and left ventricular enlargement. The estimated left ventricular ejection fraction was 35%, reflecting impaired systolic function.

In terms of the right heart, the tricuspid valve demonstrated a peak velocity (Vmax) of 4.527 m/s and a peak pressure gradient (PGmax) of 82 mmHg, resulting in an estimated systolic pulmonary arterial pressure (sPAP) of 85 mmHg and right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) of 85 mmHg, suggesting severe tricuspid regurgitation and pulmonary hypertension, with significant dilation of the RV and RA. Finally, a moderate-to-large, hemodynamically significant ASD of the ostium secundum type, measuring 18 mm (yellow arrow), was observed, with substantial left-to-right shunting (pink arrow), leading to further right atrial and ventricular enlargement (Figure 1A–D and Videos 1 and 2).

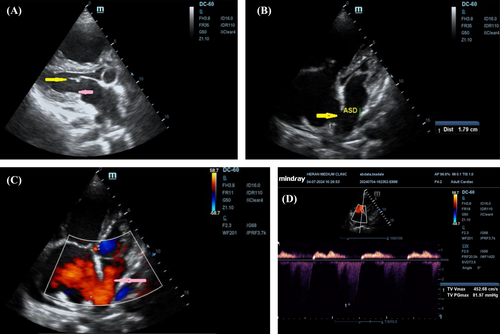

Electrocardiography performed on admission demonstrates sinus tachycardia, incomplete right bundle branch block (RBBB), and axis deviation, which is followed by p-pulmonale (Figure 2).

5 Results and Follow-Up

The patient was diagnosed with LS with acute heart failure as she had heart failure signs and symptoms. Treatment included 1 mg/kg of frusemide, oral daily 5 mg bisoprolol, oral daily 5 mg of enalapril, oral daily 12.5 mg of spironolactone, intramuscular monthly 1.2MU benzathine penicillin G, and supportive medical care with continuous monitoring for surgical treatment awaited.

6 Discussion

LS is the rare combination of congenital and/or acquired MS or MR (usually rheumatic) with a congenital ASD, or sometimes a PFO [1]. ASD may also develop iatrogenically during percutaneous mitral balloon valvuloplasty (PMBV) for those who had the procedure or spontaneously as a result of gradual stretching of the atrial septum, as probably a case in our patient, which is caused by considerable atrial enlargement in people with MS or MR [2]. This syndrome is more common among female patients and generally is more common in adults as MS is usually an acquired valvopathy following a longer period of RHD [3]. Familial occurrences have been observed; though it is an isolated case [4].

In a typical heart, blood flows from the LA to the LV through the mitral valve. However, in LS, MS impedes this flow, increasing LA pressure. The concurrent ASD provides an alternative pathway for blood to shunt from the LA to the RA, leading to right atrial volume overload. This abnormal shunting results in increased blood flow to the RV and pulmonary circulation, potentially causing pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular hypertrophy [3-5].

The pathophysiology of LS involves a complex interplay between ASD and MS. The elevated LA pressure due to MS promotes left-to-right shunting across the ASD. This shunt exacerbates right-sided volume overload, contributing to RA and RV dilation. Over time, these changes can lead to right-sided heart failure. Additionally, the increased pulmonary blood flow may result in pulmonary vascular remodeling and hypertension [3, 5]. We believe this was also the pathophysiologic cause of the ASD in our case, where a generally small ASD develops.

RHD remains a significant public health issue in sub-Saharan Africa, where it is a leading cause of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The region is characterized by high rates of ARF, particularly among children and young adults, which often progresses to RHD. Epidemiological studies have shown that RHD is more prevalent in rural areas with limited access to healthcare, and it disproportionately affects individuals in lower socioeconomic groups. In Ethiopia, RHD is a major contributor to cardiovascular disease, with studies revealing a prevalence of 1–2 cases per 1000 population. The disease burden is exacerbated by challenges such as delayed diagnosis, limited access to early medical interventions like penicillin prophylaxis, and a shortage of resources for surgical treatment [6, 7]. Despite high prevalence, there is a scarcity of reports on LS of acquired MS.

A literature review of LS in Africa reveals three reported cases. Echocardiographic findings in the reported cases of LS include: in Morocco, a 41 mm ostium secundum ASD, severe MS with a mitral valve area of 0.8 cm2, severe bi-atrial and right ventricular dilation, severe tricuspid regurgitation, and severe pulmonary hypertension (73 mmHg) [8]. In Cameroon, severe MS, a 28 mm secundum-type ASD, pulmonary hypertension (PASP = 50 mmHg), and congestive heart failure were observed [9]. In Nigeria, a 27 mm ostium secundum ASD, mild MS (mitral valve area 3 cm2), severe mitral and tricuspid regurgitations, moderate pulmonary regurgitation, pulmonary hypertension (mean pulmonary artery pressure = 51 mmHg), and biventricular diastolic dysfunction were noted [10]. These findings suggest echocardiographic findings in LS typically involve significant structural abnormalities and pulmonary hypertension, which complicate management and prognosis (Table S1).

Several key factors influence the clinical symptoms and results of LS, including the size of the ASD, the severity of the MS or MR, and the right ventricular compliance, or ability to adapt [11]. A larger ASD typically results in a more prominent left-to-right shunt—as in this case report—which can increase blood flow to the lungs and put additional strain on the right side of the heart. In severe cases of MS or MR, blood flow from the LA to the LV is restricted or the backflow regurgitant will increase, resulting in higher pressure in the left atrial and pulmonary circulation, increasing the burden on the heart and leading to heart failure symptoms with signs and symptoms of pulmonary congestion.

Furthermore, the RV's ability to handle this higher workload—known as ventricular compliance—is critical. If the RV cannot adjust to the increased pressure, it may cause right-sided heart failure, worsening the patient's condition. These combined characteristics have a substantial impact on the severity of symptoms including shortness of breath, exhaustion, and heart failure, as well as the overall prognosis and treatment strategies of the affected patients.

Treatment of LS involves a combination of medical and surgical management, tailored to the severity of the condition. Initial management includes medical therapy to control symptoms of heart failure and prevent thromboembolism, which often involves anticoagulation, diuretics, and heart failure medications such as ACE inhibitors or beta-blockers [12]. Surgical intervention, typically septal defect closure or mitral valve replacement/repair, is recommended in cases of significant MS or large ASDs causing hemodynamic compromise. However, the timing and approach depend on the patient's clinical status and available resources. Surgical outcomes are generally favorable when performed early; although in resource-limited settings, medical management remains the primary option for symptom control [12, 13].

7 Conclusion

LS is a rare and complex congenital heart disease. The existence of mitral valve lesions, especially in areas where RHD is prevalent, will result in a missed diagnosis and delay early appropriate care. Early detection with high clinical suspicion leads to earlier surgical therapy with a better patient outcome.

Author Contributions

Megersa Negesa Geleta: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, software, supervision. Endalew Damelew Liyew: data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, software, supervision, validation. Tamirat Godebo Woyimo: formal analysis, investigation, validation. Soressa Tafere Jore: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, validation. Kedir Negesso Tukeni: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, validation.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Ambo University Hospital team for their participation in the patient's care and collaboration in the preparation of this manuscript.

Ethics Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report following the journal's patient consent policy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the manuscript of this article.