Incidental Primary Angiomyolipoma of Ovary: A Rare Case Report and Literature Review

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Primary angiomyolipomas of the ovary which are not associated with genetical systemic diseases, particularly tuberous sclerosis, are extremely rare and are more likely to pose diagnostic challenges. This tumor, particularly of epithelioid variant, is more likely to be malignant and can carry a high possibility of metastasizing. Use of immunohistochemistry consisting of melanocytic biomarkers (HMB45 and Melan A) helps to ascertain their presence.

1 Introduction

Angiomyolipoma (AML) is a benign mesenchymal neoplasm that primarily affects the kidneys [1]. Despite the kidneys being the most common organs to be involved, AML has also been found in extrarenal locations, including female and male genital tracts, retroperitoneal space, and gastrointestinal tract [1, 2]. AML may either be sporadic or it may be associated with genetic and systemic diseases, particularly tuberous sclerosis (TSC) which results from TSC 1 and 2 genes mutation [2]. The sporadic variant of AML is usually unilateral, slow-growing, and it commonly affects old individuals, whereas familial variants grow fast, affect young patients, and they tend to be bilateral [3]. AML has also been reported in women with lymphangioleiomyomatosis, which is taken as a diagnostic criterion of AML, and predominant epithelial cells with atypia may be seen in about 8% of the AML variant that is associated with TSC, and a small percentage of such subtypes shows a tendency to undergo malignant transformation [4, 5]. Primary AML of the ovary is extremely rare, and this may pose diagnostic challenges to clinicians in cases of diagnosis and treatment due to the lack of evidence from large studies. We present the case of primary AML of the ovary and we also review the existing literature.

2 Case History

We present the case of a 43-year-old female with an uneventful pregnancy who was referred from a health facility due to failure to progress to the second stage of labor for almost 4 h. Her past medical and family history was uneventful. Neither did she have a family history of genetic disease nor the possibility of having TSC. In the emergency room, a general physical examination revealed normal vital signs. An obstetric examination revealed full-term size contracted uterus (fundal height = 36 weeks), longitudinal lie, cephalic presentation, occipitoposterior position, head fully engaged, fetal distress, and the cervix was fully dilated. A diagnosis of a persistent occipitoposterior positioned baby was made, and the patient was rushed to the theater. An emergency Cesarean section was performed, and both the fetus and the placenta were delivered successfully.

2.1 Diagnosis, Investigations, and Treatment

During operation, a suspicious right ovarian mass was found incidentally measuring 12.3 × 7.0 × 4.2 cm, and right oophorectomy was done. The abdomen was closed in layers, and hemostasis was achieved. The fetus weighed 3.0 kg with an Apgar score of 8, and it was resuscitated successfully. The patient was prescribed IV fluids, ceftriaxone 1 g–12 hourly, and metronidazole 500 g–8 hourly for 3 days, and she was discharged on the 4th day postoperatively.

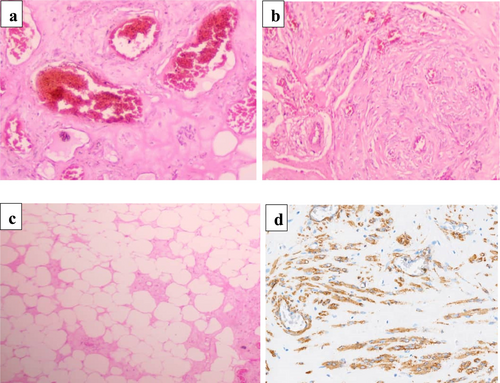

Macroscopically, the submitted specimen showed an ovarian mass that was encapsulated, ovoid, gray-brownish in color, and firm in consistency, and it measured 11.9 × 7.0 × 3.8 cm. The cut surface of the mass showed a heterogeneous, fibrous, and yellowish-tan appearance without cystic changes (Figure 1). Microscopically, the tissue sections showed complete effacement of the normal ovarian tissue by a tumor consisting of three components (mature fat, smooth muscle cells, and thick-walled blood vessels) (Figure 2a–c). All cellular lineages did not show elements of malignant features. A panel of immunohistochemistry antibody staining, consisting of SMA, HMB45, CD31, desmin, and S100, was done, and only the SMA antibody showed strong and diffuse intranuclear staining (Figure 2d) while all other antibodies were negative. Therefore, the tumor was histologically confirmed to be AML.

2.2 Outcome and Follow-Up

The patient was clinically evaluated after 1 month, and an abdominal CT scan was performed to check for the presence of hepatic or renal tumors suggestive of AML, which turned out to be negative. She was followed up for a period of 18 months, and there was no evidence of recurrence, and she is currently stable.

3 Discussion

Extrarenal cases of AML occur almost four times among females compared to males [5]. However, there are very few cases of primary ovarian AML reported in the literature. Clinically, the majority of AMLs (60%) are asymptomatic; however, about one-third of the patients report symptoms such as abdominal or flank pain, haematuria, chills, and fever [6]. Less commonly, it is symptomatic and is discovered as an incidental finding at operation for some unrelated cause or at autopsy, as it was for the present case [7]. In the present case, the patient had a vault-fistula due to obstructed labor; however, the tumor was discovered as an incidental finding during repair of the vault-fistula.

Histologically, a classical AML is a mesenchymal tumor with a noninfiltrating growth pattern [8]. It is composed of variable proportions of three components, including tortuous thick-walled blood vessels lacking elastic lamina, bundles of smooth muscle that seem to emanate from the vessel wall, and mature adipose tissue [9]. Immunohistochemically, the classical AML subtype shows a strong expression of melanocytic markers (HMB45 and Melan A) and CD117 positivity has also been reported in some cases [5, 10, 11]. For the cases of the epithelioid subtype, the epithelioid cells typically show co-expression of HMB45, Melan A, SMA, and calponin [5, 9].

The application of HMB45 and other melanocytic markers in diagnosing extrarenal AML is questionable because to date most reported extrarenal AMLs, except for hepatic AMLs, have been negative for HMB45, including the present case, although a few cases (Table 1) were positive for HMB45. The differential diagnoses of the AML, especially the epithelioid variant, include poorly differentiated tumors, both primary and metastatic tumors, of the kidneys or the liver, such as metastatic melanoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, renal cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, adrenocortical carcinoma, and oncocytoma of the kidneys [12]. However, lipoleiomyoma is a differential diagnosis of classical AML. Histologically, lipoleiomyomas are composed of variable amounts of adipocytes and smooth muscle cells, separated by thin fibrous tissue [13]. The pathogenesis of lipoleiomyoma is not clear, though fatty metaplasia of the smooth muscle cells of a leiomyoma has been thought responsible for the development of lipoleiomyomas [14]. It has also been observed that there are more cases of AML that stain positive for HMB45 compared to lipoleiomyoma [15].

| Age (years) | Laterality | Variant of AML | IHC antibody panel | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | Right | Classic | Desmin, vimentin, S-100P, Actin, and HMB-45 were positive | [16] |

| 60 | Right | Epithelioid | Strongly positive for HMB-45, h-caldesmon, desmin, SMA, TF3, CD10, ER (weak), and PR (weak) and negative for myogenin, MART, CD30, CD99, MUC4, p63, ALK, inhibin-α, MDM2, CD117, S-100, SOX10, CKpan, CKCAM5.2, and EMA | [17] |

| 54 | Left | Epithelioid | Strongly positive for H-caldesmon and SMA but focal positivity for Melan-A, HMB45, S100, c-kit, and CD34 and negative for EMA, MNF116, and calponin | [18] |

| 33 | Right | Classic | Positive for HMB45 and TF3 and negative for SMA, desmin, inhibin-α, calretinin, and CEA | [19] |

| 68 | Right | Classic | HMB45 was negative | [20] |

| 48 | Right | Classic | Positive for SMA and negative for HMB45, CD117, and S100 | Current case |

Development of AML may either be familial type, which is associated with the TSC Complex (TSC) or sporadic. The hamartin gene (TSC1) and tuberin gene (TSC2) which are found on chromosome 9q34 and 16p13, respectively, are usually involved in the pathogenesis of AML [16]. Another gene that is associated with TSC is RHEB, which is located on human chromosome 7q36 [17]. Genetic alteration in either one or both of these genes causes overgrowth of neoplastic lesions comprising of proliferating smooth muscle, vascular channels, and mature adipose tissue, with a low chance of transforming to malignancy [18]. In the work of Qin et al., it was observed that the sporadic type of AML was not associated with genetic alterations in both TSC1 and RHEB genes [19]. Their study found that 7 out of 8 cases with sporadic AML had deletion-type mutations in TSC2, and none of the cases tested had mutations for the TSC1 and RHEB genes. Mutation of TCS2 gene has been commonly associated with the development of sporadic type of AML [19]. Also, patients with high mutations for the TSC2 gene had a loss of heterozygosity (LOH) compared to cases with low mutations. In another study by Wang et al., it was reported that stopping TSC2 gene expression leads to the activation of the mTORC1 molecular signaling pathway via driving RHEB into a GDP-bound state, that is why inhibitors of mTORC1 have been found helpful in the management of patients, for example, with renal AML [20]. We did not detect mutations for any of these genes in our patient due to logistic challenges.

4 Conclusion

AML of the ovary is usually very rare and is incidentally diagnosed due to the lack of some symptoms that are usually seen in the most common type of AML, which affects the kidneys and is usually accompanied by tuberous sclerosis, in which patients tend to present with tumors from various parts of the body, including the brain. Our report has, in one way or another, helped to provide emphasis on knowing that AML of the ovary should always be considered one of the differential diagnoses for solid and benign-looking ovarian masses.

Author Contributions

James J. Yahaya: conceptualization, data curation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Emmanuel D. Morgan: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, writing – original draft. Veronica Nyakato: investigation, methodology, writing – review and editing. Emmanuel Othieno: project administration, supervision, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the team of gynecologists at Terrewode Women's Community Hospital (TWCH) for their support.

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Consent

Written informed consent was signed by the patient for the publication of the case details and any accompanying images. A copy of this consent is available upon request by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal for review purposes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.