Acute myocarditis in a young male after gastroenteritis: A case report and literature review

Abstract

A 16-year-old patient presented with acute myocarditis after gastroenteritis. His ECGs showed STEMI-like evolutionary changes. Serial troponin measurement was maximum on 3rd day. Echocardiography showed a mildly reduced ejection fraction (45%). He made an uneventful recovery after appropriate treatment. After one-month follow-up, his ECG and echo returned to normal.

1 INTRODUCTION

Myocarditis is the inflammation of the myocardium and pericarditis is the inflammation of the pericardium. When these two clinical conditions co-exist, it is termed myopericarditis or perimyocarditis. The incidence of myocarditis is under-recognized, with 1.8 million cases worldwide per year.1 Myocarditis and cardiomyopathy are the third leading cause of death among young adults, accounting for 2%–42% of sudden cardiac deaths.2, 3

2 CASE REPORT

A 16-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department (ED) with severe central chest pain, sweating, dyspnea, and palpitation. Before that, he had a 3-day history of profuse, watery diarrhea, vomiting, epigastric pain, and fever. He recalled eating some local street food. He has been fully vaccinated against COVID-19 including a booster dose. His last vaccine date was 3 months ago. Upon arrival to ED, he was in pain with blood pressure (BP) 130/80 mmHg, heart rate (HR) 100 beats per minute, temperature 100’F, and oxygen saturation (SpO2) 100% on room air. Cardiac examination was unremarkable with no audible murmurs or pericardial friction rub. Lungs were clear. Abdominal examination showed mild tenderness in the epigastric area. There was no jaundice, bleeding manifestations, or rashes.

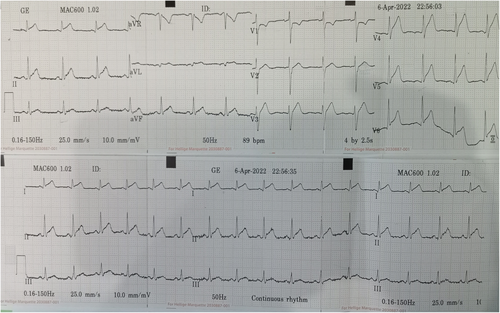

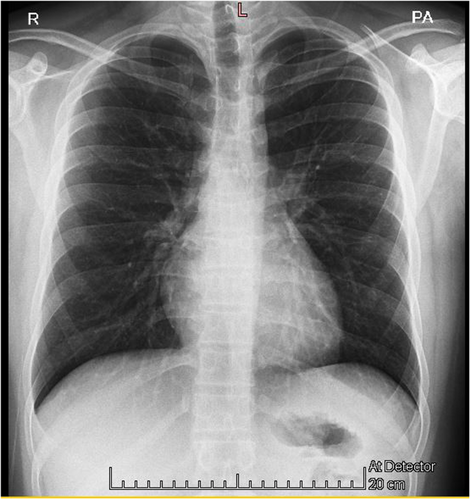

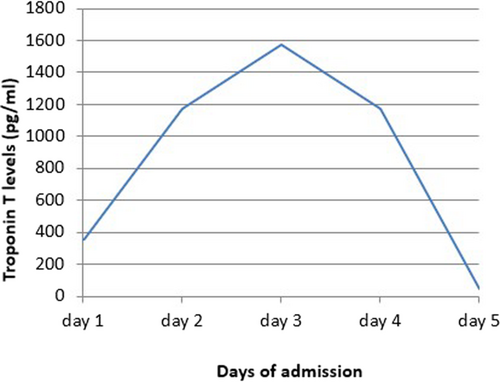

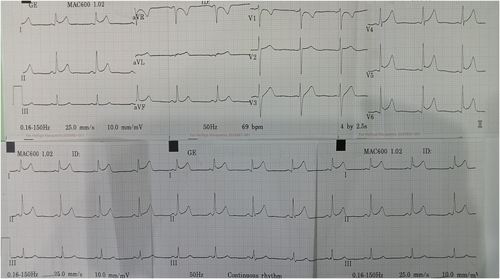

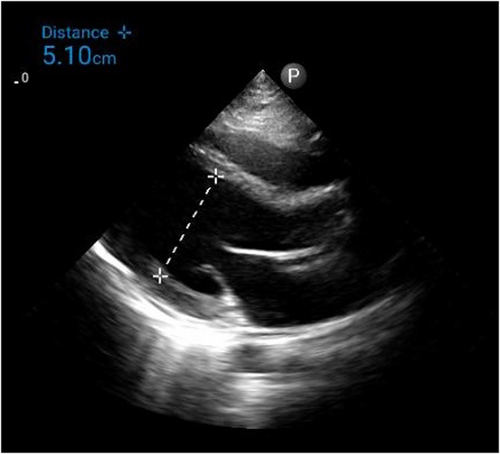

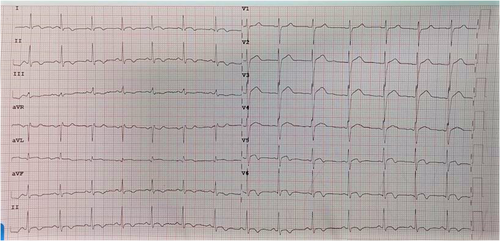

Electrocardiogram (ECG) on admission showed T inversion in aVR and V1 with ST elevation in other leads without reciprocal ST depressions. (Figure 1) Chest radiography (CXR) was unremarkable. (Figure 2) Initial troponin-T was 351 pg/ml, and a repeat assay 6 h later was 1176 pg/ml, with a maximum on the 3rd day (1573 pg/ml). (Figure 3) Other laboratory results were as follows. (Table 1) Salmonella typhi and Salmonella paratyphi A & B antigens were negative. Stool culture did not show any pathogen. The COVID-19 antigen test was negative. Serial ECG 12 h later showed new morphological changes in ST segments; ST elevation with upward concavity with notched and slurred terminal QRS. (Figure 4) Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed mildly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of approximately 45% with no regional wall motion abnormalities or pericardial effusion. (Figure 5; Video S1). Cardiac MRI and endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) have not been done due to limited resources.

| 6.4.2022 | 7.4.2022 | 8.4.2022 | 9.4.2022 | 11.4.2022 | Normal range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White cell count | 8.97 | 4.00–11.00 × 103/μl | ||||

| Hemoglobin % | 15.1 | 11.0–16.5 g/dl | ||||

| Platelet | 243 | 150–400 × 103/μl | ||||

| Urea | 3.7 | 4.5 | 2.7–8.0 mmol/L | |||

| Sodium | 142 | 140 | 135–145 mmol/L | |||

| Potassium | 3.69 | 4.33 | 3.60–5.20 mmol/L | |||

| Chloride | 105.2 | 102.6 | 98.0–107.0 mmol/L | |||

| Bicarbonate | 22.5 | 24.8 | 22.0–29.0 mmol/L | |||

| Creatinine | 106 | 107 | 59–104 μmol/L | |||

| C-reactive protein | 27.93 | 31.88 | 12.43 | ≤5.00 mg/L | ||

| HBsAg | Non-reactive | |||||

| Troponin T | 351 | 1176 | 1573 | 1173 | 46.12 | ≤14.00 pg/ml |

| Uric acid | 392 | 202–417 μmol/L | ||||

| Total cholesterol | 142.4 | ≤200 mg/dl | ||||

| Triglyceride | 118.7 | ≤150 mg/dl | ||||

| HDL | 35.7 | 35–55 mg/dl | ||||

| LDL | 86.6 | ≤130 mg/dl | ||||

| Total bilirubin | 0.413 | ≤1.2 mg/dl | ||||

| AST | 60.4 | ≤40 U/L | ||||

| Alk PO4 | 105 | 40–130 U/L | ||||

| ALT | 45.3 | ≤41 U/L | ||||

| PT | 12.4 | 10–14 s | ||||

| INR | 1.10 | |||||

| APTT | 22.3 | 25–35 s | ||||

| D dimer | 0.31 | ≤0.5 mg/L | ||||

| NT pro-BNP | 248 | <125 pg/ml | ||||

| CK-MB | 43.2 | ≤25 U/L |

- Abbreviations: Alk PO4, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine transaminase; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; AST, aspartate transaminase; CK-MB, creatine kinase-MB; HBsAg, hepatitis B antigen; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL, low density lipoprotein; PT, prothrombin time.

- Bold entries are to highlight the abnormal values.

Based on clinical symptoms, laboratory parameters, and ECG findings, post-gastroenteritis perimyocarditis was a provisional diagnosis. He was initially treated with intravenous fluids, antibiotics, prophylaxis subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin, low-dose β-blocker, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI). ECG on 3rd day showed evolutionary changes such as ST elevation falling back with diffuse T wave inversion. (Figure 6) He responded well to treatment with troponin-T level decreasing to 46.12 pg/ml. He was discharged on Day 7. At follow-up, one month after discharge, he was symptoms-free with normal LVEF and normal ECG.

3 DISCUSSION

The etiologies of myocarditis are multifactorial: infections (viral, bacterial, fungal, parasitic), systemic diseases (autoimmune, malignancy), drug hypersensitivity, and toxins.3 It occurs mostly in young males, without conventional risk factors for atherosclerosis. Inflammation of the myocardium due to direct invasion by pathogens, post-infectious immune reaction, toxic injury, or ischemic insult stimulate innate, humoral (autoreactive antibodies), and cell-mediated (T lymphocytes) immune responses. This leads to myocytes necrosis and cell death. Chronic myocarditis results in myocytes fibrosis, structural remodeling, and cardiomyopathy.4, 5 Myocarditis can present with ACS-like presentation, heart blocks, ventricular arrhythmia, cardiogenic shock, and sudden cardiac death.3 Chest pain is usually due to immune-mediated coronary vasospasm or co-existed pericarditis.

A standard 12-lead ECG is recommended in all patients.3 Sinus tachycardia, non-specific ST/T changes, and variable heart blocks are the most common. In 2012, a study by Gaetano Nucifora et al. revealed that the sum of ST-elevation (sumSTE), normalization of STE after 24 hours, and development of negative T wave, have significant relation to the extent of myocardial damage. In infarct-like myocarditis, STE is followed by gradual normalization of ST segment, and occurrence of T wave inversion.6 Perimyocarditis, should be suspected if ECG shows PR depression or STE with upward concavity, with or without terminal QRS notching or slurring.7 In our case, diffuse STE with upward concavity and both notched and slurred terminal QRS can be seen (Figure 4). Thus, we suspect both pericarditis and infarct-like myocarditis simultaneously occur.

In myocarditis, troponin levels gradually rise with a peak on the 2nd or 3rd day.8 Troponins, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and CRP levels should be measured in all patients although routine viral serology is not recommended.3 N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-proBNP) may be useful prognostic markers.

Echocardiography (Echo) is recommended by ESC for serial non-invasive monitoring of cardiac function. Cardiac MRI (CMR) has 100% sensitivity and 90% specificity in detecting.9 According to the “Lake Louise Criteria,” the presence of mid-myocardial and epicardial or patchy late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) indicates acute myocarditis.6 Cardiac computed tomography (CT) may be used if CMR is not accessible. Endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) is the gold standard to confirm the diagnosis and its etiology. However, its use is limited because of invasiveness and low sensitivity. Thus, EMB is not usually recommended except for some clinical settings.3, 10

Acute myocarditis resolves spontaneously in about 50% of cases. Physical activity should be restricted for at least 6 months. Aspirin should be used with caution and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be avoided. ACEIs or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), β-blockers, diuretics, and aldosterone antagonists can be used as heart failure therapy. Hemodynamically unstable patients may need positive inotropic agents and mechanical circulatory support. Anti-arrhythmic medications, implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD), or temporary pacemakers may be required in patients with arrhythmias or heart blocks. The role of anti-viral remains controversial. Immunosuppressive therapy may be beneficial in some cases. Other immunomodulatory therapies such as high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and immunoadsorption (IA) have been shown to improve LV function in some studies. However, larger randomized controlled clinical trials are needed to determine their efficacy and safety.3 All patients with myocarditis should undergo regular monitoring at a cardiology clinic for long-term complications.

4 CONCLUSION

Myocarditis is not uncommon in clinical practice. It should be considered an important differential diagnosis when a young patient, with no significant cardiovascular risk factors, presents with acute chest pain. A history of recent viral infection supports the diagnosis. Timely diagnosis and management is the key to improve patient outcomes. This case highlights that clinicians should be aware of this potentially lethal cardiac manifestation when treating a patient with gastroenteritis.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

May Thu Kyaw: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; resources; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Thein Myint: Conceptualization; investigation; supervision. Thant Zaw Lwin: Investigation; supervision.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The preprint publication can be found in Authorea, link: https://doi.org/10.22541/au.166686863.33849468/v1

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Not applicable.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and patient's guardian to publish this case report and any accompanying images.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data supporting the conclusions are presented in the manuscript.