Addressing the cross-country applicability of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB): A structured review of multi-country TPB studies

Abstract

The theories of reasoned action and planned behaviour (TRA/TPB) have received substantial research interest from consumer behaviourists. One important area of interest that has not been adequately researched concerns the impact of national culture on the TRA/TPB components and interrelationships. To date, no systematic assessment of the impact of culture on the TRA/TPB model relationships has been undertaken. In order to understand the potential impact of culture on the TRA/TPB model relationships, a structured review of TRA/TPB studies is undertaken. Studies that have quantitatively applied the TRA/TPB across at least two countries within a consumption domain since 2000 are reviewed. The authors propose that two of Hofstede's cultural dimensions, individualism and power distance, may moderate the TRA/TPB relationships. The review highlights that the impact of subjective norm on intention varies most across countries, with the relationship between intention and both attitude and perceived behavioural control operating more similarly across country samples. Further, a systematic assessment of variation in the TRA/TPB model relationships via multilevel modelling shows that only the subjective norm–intention relationship varies across the countries studied. The relationship between subjective norm and intention is found to be influenced by power distance, with a stronger relationship evident in high power distance cultures. This review is the first of its kind and is of significance in addressing the emic versus etic nature of the TRA/TPB. Importantly, the article outlines relevant avenues and recommendations for future cross-national research utilizing the TRA/TPB. Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Introduction

The theories of reasoned action and planned behaviour (TRA/TPB; Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975; Ajzen, 1985; 1991) have received substantial research interest. The TPB is an expectancy value model that states that behaviour is a consequence of one's behavioural intention (the cognitive representation of a consumer's motivation to enact the behaviour), which is in turn explained by the consumer's attitude (positive or negative evaluation of undertaking the behaviour), subjective norm (perceived peer pressure to enact the behaviour) and perceived behavioural control (perception of the ease or difficulty in performing the behaviour). The TPB is an extension of the TRA (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975) that does not include perceived behavioural control and thus is not designed to explain behaviours that are outside an individual's volitional control. A large number of reviews and meta-analyses have concluded favourably on the ability of the TRA/TPB to explain intention and behaviour across a wide spectrum of contexts (e.g. Albarracin et al., 2001; Armitage and Conner, 2001; Conner and Armitage, 1998; Godin and Kok, 1996; Hagger et al., 2002; Sheeran, 2002; Sheeran and Taylor, 1999; Sheppard et al., 1988; Trafimow et al., 2002; Webb and Sheeran, 2006). There is a rich and diverse literature on the use of the TRA/TPB within consumer behaviour with researchers using these theories to understand consumption contexts such as bidding in online auctions (Bosnjak et al., 2006), purchase of free-of cosmetics (Hansen et al., 2012), shoplifting (Tonglet, 2002) and exercise participation (Yap and Lee, 2013) among others.

One important area of interest that has not been examined within the TRA/TPB research domain concerns the central question as to whether the TRA/TPB can be considered to apply universally (i.e. etic) or indeed whether the TPB is culture bound (i.e. emic). This is important in order to demonstrate the model's applicability and generalizability across national boundaries. Cross-country research is important as it can ‘test the universality and generality of theories and concepts developed in relation to one country to other societies’ (Watkins, 2010 p. 709). The universal acceptance and application of the TRA/TPB have remained largely unchallenged (Malhotra and McCort, 2001), yet researchers have noted that there is a general lack of valid theories that work across countries (Maheswaran and Shavitt, 2001). The current study is the only study to date that systematically reviews studies that utilized the TRA/TPB model across more than one country. The objectives of this review are to (i) document research studies since 2000 that applied the TRA/TPB across more than one country within consumption related topics; (ii) critique the methods applied to assess differences in the TRA/TPB model relationship across countries; and (iii) determine whether the strength of the TRA/TPB model relationships vary across country samples. The findings of this review result in useful recommendations of best practice for cross-country researchers wishing to examine the universal applicability of not only the TRA/TPB but also other theories. The findings can also provide further insight into the behaviour of consumers across different countries and can potentially inform global marketing managers when designing and framing marketing messages.

Culture and its Role Within the Theory of Reasoned Action/Theory of Planned Behaviour

Culture has been defined by Hofstede (1980, p. 25) as ‘the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one human group from another’. At the country-level, culture operates through languages, education systems, social structures, religions, legal systems and so on. Cultural differences can be examined at various levels including individual, sub-unit, organizational as well as country levels (Leidner and Kayworth, 2006; Soares et al., 2007). In this review, TRA/TPB studies are examined at the country level. Separate nations are considered because ‘a culture can be validly conceptualized at the national level if there exists some meaningful degree of within-country commonality and between-country differences in culture’ (Steenkamp, 2001 p. 36). The work carried out by researchers such as Hofstede (1991) has evidenced systematic differences between countries. Furthermore, Smith and Schwartz (1997) examined cultural differences within regions of China, Japan and the USA but actually found much larger differences between the three countries. An examination of culture at the country level can therefore provide a better understanding than an analysis of within-country factors as to why individuals from one country (as against others in a different country) behave the way they do. Indeed, Hofstede (1991, p. 12) asserts that nations ‘are the source of considerable amount of common mental programming of their citizens’.

The examination of the TRA/TPB across countries can improve our understanding of the same behaviour across various cultures. In particular, researchers can learn whether and to what extent the model is culturally sensitive. Ajzen (1991) expected that the three components would predict intention equally well across samples and cultures. However, the claim that the TRA/TPB applies universally (i.e. etic) is contested by the extent to which the TRA/TPB components and their interrelationships are dependent on country/cultural characteristics. Researchers (e.g. Kirkman et al., 2006) have asserted that cultural values may moderate relationships such as those present in the TRA/TPB and earlier findings do suggest that the TRA/TPB works differently in different cultures. For example, in Lee and Green's (1991) study, the importance of attitudes and social norms in determining behavioural intentions were substantially different across Korean and American participants with social norms having a stronger impact on intentions in Korea, a collectivistic culture. More recently, Riemer et al. (2014) argued that the roles of attitude and norms on intention and behaviour are affected by cultural factors such as Hofstede's individualism/collectivism dimension. Hofstede's (1980) framework is the most widely used cultural framework in marketing and is useful for formulating hypotheses in cross-cultural studies (Rabl et al., 2014; Soares et al., 2007). Drawing on Hofstede's framework, we outline possible ways in which culture (at the country level) may influence the TPB model relationships. In line with Rabl et al. (2014) and Zaheer et al. (2012), we decided to focus on a small number of the most relevant cultural dimensions to ascertain whether these dimensions moderate the relationship between intention and its antecedents. For the purpose of the current study individualism–collectivism and power distance are chosen as the two Hofstede dimensions that have received the most empirical attention (Taras et al., 2010).

- P1 The effect of attitude on intention will be stronger in countries high in individualism than in countries low in individualism.

- P2 The effect of subjective norm on intention will be stronger in countries high in collectivism than in countries low in collectivism.

- The effect of attitude on intention will be weaker in countries high in power distance than in countries low in power distance.

- The effect of subjective norm on intention will be stronger in countries high in power distance than in countries low in power distance.

- The effect of perceived behavioural control on intention will be stronger in countries low in power distance than in countries high in power distance.

The five propositions given above provide a theoretical viewpoint as to how the TRA/TPB relationships may be influenced by culture, but if Ajzen's (1991) assertion that the TRA/TPB applies universally is correct these propositions will fail to be supported. Understanding these proposed effects is important for consumer behaviour researchers as increasingly the internet provides companies the opportunity to trade across the globe. It is thus important to take account of country-specific factors that would influence how consumer intentions and behaviours are formed across different countries.

Method

To achieve the objectives of this review, past studies were selected for inclusion if they met the following criteria. Firstly, the studies had to be a quantitative application of the TRA or TPB. Further, studies (e.g. Singh et al., 2006) that drew on the TRA/TPB but did not operationalize the TRA/TPB constructs as specified by Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) or Ajzen (1985; 1991) were excluded. For example, Singh et al. (2006) utilized the TPB as an overarching theory but captured the constructs differently (for instance, measuring ease of navigation as a surrogate for perceived behaviour control). Secondly, studies were required to be related to consumer behaviour and as a result must have explored a consumption context. Here, a broad view of consumption was taken to include papers that not only examined consumer purchases but examined individuals' behaviours and decision making in a range of consumption categories such as health promotion/prevention, adopting technology as well as philanthropic consumption acts. Thirdly, studies must have examined data from at least two different countries and reported in sufficient detail on the interrelationships posited by the TRA/TPB for each country so as to meet the requirement for comparison on the TRA/TPB relationships across the countries studied. Fourthly, this review included studies published since 2000, as the number of studies applying the TRA/TPB has intensified since then and researchers have begun questioning whether the TRA/TPB is applicable universally (Malhotra and McCort, 2001). Lastly, this review included only articles published in English language peer reviewed journals and excluded other pertinent contributions from books, theses, online publications and conference publications.

Given the diversity of topics that could be classified as consumption related, the authors did not use any specific terms related to consumption during their literature search. Rather the focus was on identifying all TRA/TPB published research studies, which were undertaken across different countries. The authors began by searching for Ajzen's (1991) article in the Web of Science database and conducted a cited reference search (within Web of Science) that identified all published articles that had cited Ajzen's (1991) article. Within this set of 7,303 articles (as of 28th March 2013) that had cited Ajzen's (1991) article, the authors searched for articles that contained target texts using a mixture of terms: ‘countries’, ‘cross-cultural’, ‘cross-national’ and ‘cross-country’. Examination of the titles and abstracts in the result of this search led to the identification of 350 articles with a cross-country application of the TRA/TPB. Google Scholar was also used to locate Ajzen's (1991) article and then identify subsequent articles that had cited Ajzen's (1991) article (by clicking on the ‘cited by…’ tab underneath the listing). Among this set of articles, similar search terms were applied identifying around 150 articles. To identify additional TRA studies, which might not have cited Ajzen's (1991) work, a search on Google Scholar was conducted using a combination of the search terms: ‘countries’, ‘theory of reasoned action’, ‘TRA’, ‘cross-cultural comparison’, ‘cross-national comparison’, ‘cross-country comparison’ ‘attitude’, ‘subjective norm’ and ‘consumer’. The authors also conducted cited reference searches on three consumer related articles (Bagozzi et al., 1991; Lee and Green, 1991; Malhotra and McCort, 2001), which are frequently cited in studies that apply the TRA across countries. Last, the authors examined the references cited in articles selected for the review to further check for any missed articles. As a result of the above process, approximately 400 articles were identified for further examination. The lead author scrutinized the abstracts of these articles against the inclusion criteria and identified 79 where the full text required detailed examination. Careful scrutiny of the full texts showed 53 articles to be deemed not to fit the inclusion criteria by the lead author. A second author independently conducted the same detailed full text examination of the 79 articles and verified that most of the articles should be excluded but had reservations about the exclusion of three. After discussions between all the authors, these three articles were also included in the review giving the final number of papers to be included in the review as 29.

For this review (Table 1), the authors extracted a number of attributes beyond the basic information (authorship, source, publication date, context, population and countries studied) on each article reviewed. Given the distinction between the TRA and the TPB, the authors recorded whether the TRA or the TPB is utilized in each study. To examine the strength of the evidence regarding the emic versus etic nature of the TRA/TPB model, information on the significance of the paths hypothesized in the TPB model for each of the countries studied was extracted. Comments are given on the explanatory power (R2) of the TRA/TPB for both intention, and where possible behaviour, across each country. The review records additional explanatory variables, impacting intention or behaviour, that were included along with the TRA/TPB antecedents so that the reader can meaningfully compare the R2 values across the studies reported. The review also documents the assessment of three key methodological considerations. These pertain to firstly the translation method employed in the development of the questionnaire, secondly whether an assessment of measurement invariance was undertaken and the level of invariance established and finally whether statistical differences in the strength of the structural paths in the TRA/TPB model were examined. Translation equivalence and measurement invariance need to be established in order to ensure that the meaning of the TRA/TPB constructs in each study were comparable across country samples. This issue is imperative for researchers to make valid cross-country comparisons (Watkins, 2010). For completeness in our reporting and to allow for comparisons across the studies reported, the analytical approach (e.g. multiple regression) adopted is also recorded. From a theoretical point of view, it is important to note the rationale behind the selection of the chosen countries; thus, information is extracted on the criteria for the selection of the countries used in each study and relatedly the nature of any cross-country hypotheses posited.

| Authors (year) | Journal | Context and (population) | Countries (sample size analysed) | TRA/TPB | Augment model | Country choice reason | Country-level hypotheses Y/N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Arvola et al. (2008) |

Appetite | Purchasing organic food, apples and pizza (food shoppers) | Italy (n = 202), Finland (n = 270), UK (n = 200) | TPB (Int) | Yes | Context | No |

|

Bagozzi et al. (2000) |

Journal of Consumer Psychology | Fast food restaurant consumption (students) | US (n = 246), Italy (n = 123), Japan (n = 419), China (n = 264) | TRA (Int) | No | Culture | Yes |

|

Chai and Pavlou (2004) |

The Journal of Enterprise Information Management | E-commerce adoption (online consumers) | US (n = 181), Greece (n = 70) | TPB (Int) | No | Culture | Yes specific |

|

Chan and Lau (2002) |

Journal of International Consumer Marketing | Purchasing green products (consumers) | US (n = 213), China (n = 232) | TPB | No | Culture | Yes specific |

|

Cheng and Ng (2006) |

Journal of Applied Social Psychology | Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) prevention (consumers) | China (n = 75), Hong Kong (n = 75), Singapore (n = 75), Canada (n = 75) | TPB | Yes | Context and Culture | No |

|

Cordano et al. (2011) |

Environment and Behaviour | Pro-environmental behaviour (students) | US (n = 256), Chile (n = 310) | TRA (Int) | No | Culture | No |

|

Dinev et al. (2009) |

Information Systems Journal | Using protective information technologies-anti-spyware (students) | US (n = 332), South Korea (n = 227) | TPB (Int) | Yes | Culture | Yes specific |

|

Hagger et al. (2005) |

Journal of Educational Psychology | Leisure-time physical activity (high school pupils) | Britain (n = 222), Greece (n = 93), Poland (n = 103), Singapore (n = 133) | TPB | Yes | Culture | Yes |

|

Hagger et al. (2007) |

Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology | Leisure-time physical activity (high school pupils) | Britain (n = 432), Estonia (n = 268), Greece (n = 150), Hungary (n = 235), Singapore (n = 133) | TPB | No | Culture | Yes |

|

Hagger et al. (2009) |

Psychology and Health | Leisure-time physical activity (high school pupils) | Britain (n = 210), Estonia (n = 268), Finland (n = 127), Hungary (n = 235) | TPB | Yes | Culture | Yes |

|

Heeren et al. (2007) |

AIDS Education and Prevention | Condom use (students) | US (n = 160), South Africa (n = 251) | TPB (Int) | No | Not given | No |

|

Januszewska and Viaene (2001) |

Journal of Euromarketing | Chocolate consumption (consumers) | Belgium (n = 429), Poland (n = 463) | TPB (Int) | No | None | No |

|

Jin et al. (2012) |

The Journal of the Textile Institute | Apparel shopping (shoppers) | China (n = 724), India (n = 551) | TPB (Int) | Yes | Culture | Yes specific |

|

Mafe et al. (2010) |

Journal of Service Management | Use SMS to participate in TV programmes (mobile users) | Columbia (n = 259), Spain (n = 205) | TPB (Int) | Yes | Context | No |

|

Malhotra and McCort (2001) |

International Marketing Review | Purchasing athletic shoes (students) | US (n = 225), Hong Kong (n = 215) | TRA (Int) | No | Culture | Yes |

|

Muk (2007) |

International Journal of Advertising | Opt in to SMS advertising (students) | US (n = 160), Korea (n = 152) | TRA (Int) | No | Culture | Yes |

|

Muk (2012) |

Journal of Direct, Data and Digital Marketing Practice | Redeem SMS coupons (students) | US (n = 171), Korea (n = 154), Taiwan (n = 198) | TPB (Int) | Yes | Culture | Yes |

|

Olsen et al. (2008) |

Food Quality and Preference | Consume fish burgers (pupils, parents and students) | Norway (n = 110 pupils and n = 149 parents) Spain (n = 175 students) | TPB (Int) | No | Culture | No |

|

Olsen et al. (2010) |

Appetite | Consume ready-to-eat meals (consumers) | Norway (n = 112), The Netherlands (n = 99), Finland (n = 134) | TRA (Int) | No | Context | No |

|

Pavlou and Chai (2002) |

Journal of Electronic Commerce Research | E-commerce transaction (consumers) | China (n = 58), US (n = 55) | TPB (Int) | No | Culture | Yes specific |

|

Quintal et al. (2010) |

Tourism Management | Visit Australia on holiday (residents with various travel experience) | South Korea (n = 402), China (n = 443), Japan (n = 342) | TPB (Int) | No | Context and culture | No |

|

Ries et al. (2012) |

European Physical Education Review | Leisure-time physical activity (pupils) | Estonia (n = 146), Spain (n = 251) | TPB | Yes | Culture | No |

|

Ruiz de Maya et al. (2011) |

Ecological Economics | Purchasing organic fresh tomatoes or organic tomato sauce (consumers) | Denmark (n = 1003), Finland (n = 855), Germany (n = 999), Greece (n = 1043), Italy (n = 1000), Spain (n = 1006), Sweden (n = 1128), UK (n = 980) | TPB (Int) | No | Not given | Yes |

|

Saba et al. (2008) |

International Journal of Consumer Studies | Vegetable soup preparation (seniors 65+) | Germany, Denmark, Spain, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Sweden and UK (n = 96 in each country) | TPB (Int) | Yes | Not given | No |

|

Soyez (2012) |

International Marketing Review | Pro-environmental behaviour (consumers) | US (n = 169), Canada (n = 283), Australia (n = 214), Russia (n = 204), Germany (n = 226) | TPB (Int) | No | Culture | Yes specific |

|

Tsai and Coleman (2005) |

Annals of Leisure Research | Active recreation participation (students) | Australia (n = 991), Hong Kong (n = 892) | TPB | No | Culture | No |

|

Warner et al. (2009) |

Accident Analysis and Prevention | Comply with speed limit (drivers) | Sweden (n = 219), Turkey (n = 252) | TPB (Int) | No | Culture | No |

|

Yun and Park (2010) |

Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology | Organ donation (students) | US (n = 246), Korea (n = 275) | TPB (Int) | No | Context and culture | No |

|

Yang and Jolly (2009) |

Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services | Mobile data service adoption (consumers) | US (n = 200), Korea (n = 200) | TRA (Int) | Yes | Context and culture | Yes specific |

- Notes: Int = intention; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States of America; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; TV, television; SMS, SHORT MESSAGE SERVICE; TRA, theory of reasoned action; TPB, theory of planned behaviour.

To provide further evidence on the emic versus etic nature of the TRA/TPB and to test the propositions developed two methods of analysis were applied to the data collected as part of this review. Firstly, pair-wise tests of difference in the correlations for each of the three TPB relationships reported within a reviewed article were undertaken where possible. Specifically, if an article reported correlation values (and sample sizes) for one of the TPB model relationships across two or more country samples, then a formal assessment based on Fisher's Z-test was undertaken to conclude if the correlation values differed across a pair of country samples. In articles where unstandardized beta values and associated standard errors (or t values) were reported (but not the correlation values), a test of difference in the beta weights across the two country samples was undertaken. The results of these formal tests are reported (see italic results in Table 2) to provide additional aid to the reader in interpreting the cross-country results. However, this piece-meal approach in assessing cross-country variations in the TRA/TPB model relationships does not allow a rigorous examination of the propositions posed in the current research. To overcome this limitation, a second systematic analysis was also undertaken. Thus, multilevel modelling (via hierarchical linear modelling: HLM) was used to assess if the strength of the relationship between intention and its antecedents (attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioural control) varied across the countries included in the review. The HLM analysis assesses if cross-country variations can be systematically explained by the Hofstede dimensions as proposed. The data for this analysis is based on extracting the correlation value, or when the correlation value is not reported the standardized beta weight adjusted using the formula provided by Peterson and Brown (2005). In order to take into account that a number of correlation values are provided within each article, dummy variables were used to control for within article variations. Articles were included in the HLM analysis if data were obtainable within each country sample for two correlation values (for the TRA) or for all three correlation values (for the TPB). In total 67 level-1 cases (covering 24 articles across 17 countries) were used to examine the impact of the Hofstede country-level dimensions on the two TRA relationships. However, a number of articles did not cover the full TPB model and so only 52 level-1 cases (covering 19 articles across 16 countries) were used to examine the impact of the Hofstede dimensions on the perceived behavioural control–intention relationship. Country-level scores for the two Hofstede dimensions were retrieved from Hofstede's website (http://geert-hofstede.com/countries.html).

| Authors (year) | Analysis method (s) | Cross-country test | Translation method used | VarInvar level | Effect size | Key findings from article summarized |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Arvola et al. (2008) |

SEM | No | Translation back-translation | Full metric (chi-sq diff) | Italy (R2apple = 0.74 R2pizza = 0.64), Finland (R2apple = 0.51 R2pizza = 0.56), UK (R2apple = 0.65 R2pizza = 0.45). | PBC dropped because of ‘insignificant contribution to prediction of intentions and because of problems with estimation’ (low reliability). Regression weights varied (in significance and strength) across national samples. For apple study there is a sig. diff. for Att ➔ Int between Italy and Finland. For the pizza study there are sig. diff. between Att ➔ Int for: Italy and Finland; Italy and UK. With sig. diff. in the SN ➔ Int path for: Italy and UK; Finland and UK. |

|

Bagozzi et al. (2000) |

SEM | Yes | Translation back-translation | Not tested | US (R2alone = 0.33 R2friend = 0.19), Italy (R2alone = 0.16 R2friend = 0.07), Japan (R2alone = 0.10 R2friend = 0.05), China (R2alone = 0.08 R2friend = 0.02). | Numerous differences found across the four country clusters with the TRA operating differentially. |

|

Chai and Pavlou (2004) |

MR | No | Translation back-translation | Not tested | None given | Att ➔ Int sig. in both countries but SN and PBC sig. only in US. 10% level sig. diff. in SN ➔ Int path. |

|

Chan and Lau (2002) |

SEM | Yes | Translation back-translation | Not tested | US (R2beh = 0.40), China (R2beh = 0.34). R2int not reported. | Att ➔ Int found to be invariant across the two countries. But SN ➔ Int, Int ➔ Beh and PBC ➔ Int not invariant. With SN and PBC exerting a stronger influence on Int for Chinese consumers. Int ➔ Beh was stronger for American consumers. |

|

Cheng and Ng (2006) |

MR | No | Translation back-translation | Not tested | China (R2int = 0.45 R2beh = 0.43), Hong Kong (R2int = 0.54 R2beh = 0.48), Singapore (R2int = 0.56 R2beh = 0.44), Canada (R2int = 0.56 R2beh = 0.42). | Support for TRA in predicting preventative behaviours across all countries but support for TPB only shown for Hong Kong, Singapore and Canada. |

|

Cordano et al. (2011) |

MR | No | Translation back-translation | Not tested | Chile (R2int = 0.50), US (R2int = 0.49). | Att ➔ Int NS for Chilean sample but SN ➔ Int sig. TRA applies in US sample. |

|

Dinev et al. (2009) |

SEM | Yes, for each hypothesized path | Translation back-translation | Not tested | None given | SN ➔ Int sig. in South Korean sample but not US sample. Att ➔ Int and PBC ➔ Int sig. in both countries. |

|

Hagger et al. (2005) |

Path analysis | Yes | Translation back-translation | Partial metric (No chi-sq diff) | UK (R2int = 0.45 R2beh = 0.20), Greece (R2int = 0.46 R2beh = 0.22), Poland (R2int = 0.63 R2beh = 0.57), Singapore (R2int = 0.43 R2beh = 0.44). | PBC ➔ Int, Int ➔ Beh are sig. in all countries with SN ➔ Int NS for all countries. For the Singaporean sample Att ➔ Int was NS while sig. in all other countries. |

|

Hagger et al. (2007) |

SEM | Yes | Translation back-translation | Full metric (No chi-sq diff) | UK (R2int = 0.56 R2beh = 0.55), Estonia (R2int = 0.58 R2beh = 0.52), Greece (R2int = 0.73 R2beh = 0.24), Hungary (R2int = 0.24 R2beh = 0.21), Singapore (R2int = 0.48 R2beh = 0.59). | The TPB model operates similarly with the exception of the Hungarian sample. Att ➔ Int and Int ➔ Beh sig. in all countries. SN ➔ Int only sig. for Hungarian sample. PBC ➔ Int sig. in all countries except Hungary. |

|

Hagger et al. (2009) |

Path analysis | Yes | Translation back-translation | Full metric (no chi-sq diff) | UK (R2int = 0.70 R2beh = 0.53), Estonia (R2int = 0.59 R2beh = 0.50), Finland (R2int = 0.65 R2beh = 0.52), Hungary (R2int = 0.45 R2beh = 0.23). | Significant cross-country variations found in SN ➔ Int and PBC ➔ Int with the TPB model operating similarly for the British and Hungarian samples whereby SN ➔ Int sig. but PBC ➔ Int NS. All countries Att ➔ Int and Int ➔ Beh sig. |

|

Heeren et al. (2007) |

MR | Yes | None reported | Not tested | US (R2int = 0.53), South Africa (R2int = 0.35). | SE ➔ Int sig. for South Africa but not US. Att ➔ Int and SN ➔ Int sig. in both countries but paths stronger in the American sample. Sig. interactions found between country and each of the TPB antecedents. |

|

Januszewska and Viaene (2001) |

MR | No | Translation only | Not tested | Belgium (R2int = 0.13), Poland (R2int = 0.15). | Att ➔ Int sig in both country samples with SN ➔ Int NS in both and PBC sig. only in Poland. |

|

Jin et al. (2012) |

SEM | No | Translation back-translation | Configural | Not given | The same pattern of effects was found across the two countries with sig. relationships between Att ➔ Int, SN ➔ Int and external PBC ➔ Int (not internal). |

|

Mafe et al. (2010) |

SEM | Yes | None reported | Not tested | Columbia (R2int = 0.39), Spain (R2int = 0.49). | Att ➔ Int sig. in both countries. No direct effect of PBC ➔ Int. SN ➔ Int only sig. in Columbia. |

|

Malhotra and McCort (2001) |

SEM | No | Translation back-translation | Not tested | US (R2direct = 0.66 R2belief = 0.40), Hong Kong (R2direct = 0.21 R2belief = 0.34). | TRA model applicable across both countries. Sig. diff. in both Att ➔ Int and SN ➔ Int paths. |

|

Muk (2007) |

MR | No | Translation back-translation | Not tested | US (R2int = 0.27), Korea (R2int = 0.32). | Country coded as a dummy variable (NS) in the combined analysis. SN ➔ Int NS in both countries but Att ➔ Int sig. Sig. diff. in Att ➔ Int path. |

|

Muk (2012) |

MR | No | Translation back-translation | Not tested | US (R2int = 0.27), Korea (R2int = 0.39), Taiwan (R2int = 0.31). | Att ➔ Int and PBC ➔ Int sig. in both the American and Korean samples. For the Taiwanese sample Att ➔ Int and SN ➔ Int were the only sig. TPB paths. SN ➔ Int was NS for the American and Korean samples. Sig. diff. in Att ➔ Int path (10% level) and PBC ➔ Int path. |

|

Olsen et al. (2008) |

SEM | No | Translation only | Partial metric and partial scalar (no chi-sq diff) | Not given | Individual country path results are not given, but nested model analyses show that there are no differences in the structural relationships of the TPB model across the three groups of young Norwegian, Norwegian parents and young Spanish. Sig. diff. in PBC ➔ Int path for young consumer (not tested for adult sample). |

|

Olsen et al. (2010) |

MR | No | None reported | Not tested | Norway (R2int = 0.15), Netherlands (R2int = 0.19), Finland (R2int = 0.20). | PBC was dropped from the analysis as factor analysis results do not show the PBC items to be discriminant. Att ➔ Int sig. in all countries but SN ➔ Int sig. in only Norway and Finland. |

|

Pavlou and Chai (2002) |

MR with country dummy | Yes (via country dummy variable moderated regression) | Translation back-translation | Not tested | US (R2int = 0.33), China (R2int = 0.77). | Att ➔ Int and SN ➔ Int only sig. in China with PBC ➔ Int sig. in both the US and China. Moderated regression analysis revealed sig. interactions between country and each of the TPB antecedents in determining intention. However the path between social influence ➔ Int was NS moderated by culture while SN ➔ Int was moderated by culture. |

|

Quintal et al. (2010) |

Path analysis | No | Translation back-translation | Not tested | South Korea (R2int = 0.21), China (R2int = 0.44), Japan (R2int = 0.34). | Att ➔ Int only sig. in Japan, SN ➔ Int and PBC ➔ Int sig. in all three countries. Sig. diff. between South Korea and China for all TPB paths (PBC ➔ Int 10% level). Diff. between China and Japan for SN ➔ Int and PBC ➔ Int. |

|

Ries et al. (2012) |

SEM | No | Translation back-translation | Full metric (not chi-sq diff) | Not given | Similar results for both country samples, with Att ➔ Int, PBC ➔ Int and Int ➔ Beh sig. but not SN ➔ Int. |

|

Ruiz de Maya et al. (2011) |

SEM | Yes (but not for each TPB path) | Translation back-translation | Complete equivalence across samples (not chi-sq diff). | Not given | Numerous differences found across the four country clusters with the TPB operating differentially. |

|

Saba et al. (2008) |

MR | No | Translation back-translation | Not tested | Germany (R2int = 0.92), Denmark (R2int = 0.87), Spain (R2int = 0.77), Italy (R2int = 0.93), Poland (R2int = 0.91), Portugal (R2int = 0.92), Sweden (R2int = 0.95), UK (R2int = 0.93). | Stepwise approach used. Similar results for the German and Danish samples (affective Att most important determinant of Int); Swedish and UK samples (affective Att and PBC); Spain and Portugal (cognitive Att); Italy (PBC followed by SN); Poland (PBC). |

|

Soyez (2012) |

SEM | Yes | Translation back-translation | Full metric invariance (chi-sq diff) and partial scalar invariance. | US (R2int = 0.80), Canada (R2int = 0.73), Australia (R2int = 0.58), Germany (R2int = 0.72), Russia (R2int = 0.54). | NS differences found in TPB regression paths across the five countries except for one path where SN ➔ Int differs across Germany and Australia. |

|

Tsai and Coleman (2005) |

SEM | No | Translation back-translation | Not tested | Australia (R2int = 0.78 R2beh = 0.42), Hong Kong (R2int = 0.83 R2beh = 0.35). | Used 1% sig level. SN ➔ Int NS for both countries. Att ➔ Int, PBC ➔ Int and Int ➔ Beh sig. in both countries. PBC ➔ Beh only sig. in Hong Kong. |

|

Warner et al. (2009) |

SEM | No | Translation back-translation | Not tested | Sweden (R2int = 0.85), Turkey (R2int = 0.84). | SN ➔ Int NS for Swedish sample but Att ➔ Int and PBC ➔ Int sig. in both countries. SN ➔ Int also sig. in Turkey. |

|

Yun and Park (2010) |

MR with country dummy | Yes (via country dummy variable moderated regression) | Translation only | Not tested | Not given | In terms of explaining intentions to have a family discussion about organ donation, only the path between SN ➔ Int was moderated by culture, with the path stronger among the American sample. Regarding intentions to sign up for organ donation, both the paths between Att ➔ Int and PBC ➔ Int were moderated by country with Americans having a stronger Att ➔ Int path but a NS PBC ➔ Int path and Koreans a significant PBC ➔ Int path. |

|

Yang and Jolly (2009) |

SEM | No | Translation back-translation | Full metric and scalar (but no chi-sq diff) | Not given | SN ➔ Int NS for Korean sample, sig. for US sample. Att ➔ Int sig. for both countries. |

- Notes: Behaviour is only discussed where measures were collected at a subsequent point in time; augment model means that other measures beyond the TPB were included in the prediction of intention.

- Results in italics relate to additional tests undertaken by the authors.

- TPB, theory of planned behaviour; TRA, theory of reasoned action; Int, Intention; Att, attitude; chi-sq, chi-squared; sig., significant; SN, subjective norm; Beh, behaviour; SEM, structural equation modelling; MR, multiple regression; PBC, perceived behavioural control; SE, self-efficacy; diff, difference.

- p < 0.05 used unless otherwise stated.

Findings of the Review

The discussion of the articles identified in this review is organized as follows. First, an overview of articles identified is presented before moving on to discuss substantial methodological and theoretical issues arising from the findings as presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Context, source and theory applied

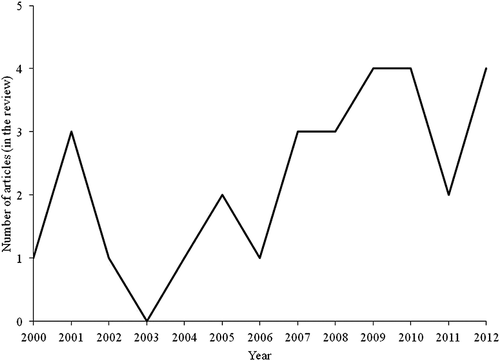

The articles included in this review investigated the impact of culture on the TRA/TPB across a range of consumer contexts including food purchases, leisure activities, pro-environment behaviours, technology usage and health choices. The most common consumption issues explored were technology and food consumption. Most of the articles were published in context-related journals (e.g. Appetite) with some published in mainstream marketing journals (e.g. International Marketing Review and Journal of Consumer Psychology). Figure 1 shows that a greater number of the studies reviewed were conducted toward the end of the review period.

The majority (23 out of 29) of the articles reviewed employed the TPB while six employed the TRA. Only seven of these studies captured behaviour at a later time period from intention. In terms of augmenting the TRA/TPB, around a third (11 out of 29) of the studies included additional constructs as antecedents of either intention or behaviour.

Countries and samples studied

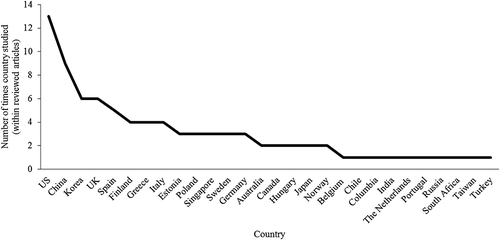

The average number of countries studied was three with over half (16 out of 29) examining only two countries. Researchers (e.g. Franke and Richey, 2010) recommend the use of at least seven to ten countries to explore cross-national phenomena. Only two articles, each investigated eight countries, met this criterion (Ruiz de Maya et al., 2011; Saba et al., 2008). Figure 2 provides a breakdown of the frequencies of countries investigated across the articles reviewed. The figure shows that the US, China, South Korea and the UK were the most popular countries chosen. In total, 28 different countries spanning all the continents except Antarctica were examined with ten countries examined only once. Very few studies included countries in Africa or South America.

Regarding the rationale for the choice of countries, the reason most frequently given was cultural differences (e.g. based on Hofstede's dimensions) with some based on context specific reasoning. In some articles, (e.g. Ruiz de Maya et al., 2011; Saba et al., 2008) little or no discussion was provided on the choice of countries selected. The lack of rationale behind the selection of the countries chosen was also evidenced in the nature of country-level hypotheses formulated. Almost half of the articles (14 out of 29) failed to develop country-level hypotheses of any kind. Only seven of the articles formulated specific country-level hypotheses for one or more of the relationships in the TRA/TPB model. A further eight articles offered more general hypotheses stating an expectation of either no or some country/cultural differences.

Both student and mainstream consumer samples were common and sample sizes were mainly satisfactory, with most analysing samples of approximately 200 per country. A small number of studies utilized sample sizes, which were much higher and closer to 1000 per country which make statistical tests more sensitive thus yielding more significant results (e.g. Ruiz de Maya et al., 2011; Tsai and Coleman, 2005). One exception that utilized small sample sizes (of around 50) was Pavlou and Chai (2002), and the results of this study should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Measurement issues

In terms of questionnaire design, only three of the articles failed to report the questionnaire translation method used. Apart from three that used one-way translation only, all others employed translation-back-translation as proposed by Brislin (1986) to ensure that questionnaire items had equivalent meanings in their chosen countries. Some studies failed to report fully the items utilized in the research and this limited the authors' ability to comment on whether Ajzen's (1991) guidelines regarding target, action, context and time were adhered to (see Table 2 for specific studies).

An assessment of measurement invariance was undertaken and reported in only a third (10 out of 29) of the articles. Measurement invariance refers to ‘whether or not, under different conditions of observing and studying phenomena, measurement operations yield measures of the same attribute’ (Horn and McArdle, 1992 p. 117). Establishing measurement invariance is particularly important in cross-country research because when constructs are measured in different countries, one cannot assume that the scores obtained will have identical meaning and thus be comparable across the country samples (Watkins, 2010). Steenkamp and Baumgartner (1998) outlined six levels of invariance with increasing levels of cross-sample constraint conditions covering configural, metric, scalar, factor covariance, factor variance and error variance invariance. These authors also stated that ‘in practical applications, full measurement invariance frequently does not hold, and the researcher should then ascertain whether there is at least partial measurement invariance’ (p. 81). Metric invariance assesses if the first-order factor loadings are equal across country samples. Achieving metric invariance ensures that the scores on the measurement items can be meaningfully compared across countries. When the purpose of the research is to explain variance in a focal dependent construct by a set of independent constructs, metric (or partial metric) invariance needs to be established. Even if the items measuring a latent factor possess equivalent metrics across country samples, additional assessment of scalar invariance (i.e. equality of measurement intercepts) is needed to assure comparability of latent means across countries. Thus, scalar invariance is important if researchers want to comment on how the average values of the TPB constructs differ across the countries studied.

Of the 10 studies that reported measurement invariance, two approaches were taken to compare the assessment of invariance, firstly the likelihood ratio test based on the chi-square statistic, as recommended by Steenkamp and Baumgartner (1998), and secondly a comparison of goodness-of-fit indices, as recommended by Chen (2007). Using either method as reported in Table 2, nine of the studies were able to evidence at least partial metric invariance. However, few studies reported scalar invariance with only three studies achieving at least partial scalar invariance. One study (Ruiz de Maya et al., 2011) evidenced all six levels of invariance based on Chen (2007), thus concluding the complete equivalence of the TPB across the eight countries studied. It is worrying that a majority of the studies failed to demonstrate measurement invariance as readers cannot be confident that the reported cross-country comparisons are valid.

Statistical testing of model relationships and explanatory power of the TRA/TPB

Statistical tests for cross-country differences in the TRA/TPB structural/regression paths were conducted in only 12 of the studies. Overall, the majority of the articles revealed the presence of notable cross-country variations in the TRA/TPB model relationships. It is apparent from Table 2 that very few studies statistically tested for cross-country differences in the structural paths. A common finding across the articles examined in this review is that conclusions are incorrectly drawn based on whether or not a component exerts a statistically significant impact on intention (or behaviour) in each country sample. Conclusions based on such reasoning are problematic because the significance test assesses if the regression weight within a country sample is significantly different from zero, with the test statistic being a function of the sample specific standard error. Large differences in the standard errors across the country samples may result in similar beta weights with different statistical significance results (p values). For example, Warner et al. (2009) found that subjective norm did not impact intention in Sweden (β = 0.06, p > 0.05), while in Turkey, subjective norm did impact intention (β = 0.09, p < 0.05). One might be tempted to suggest a cross-country difference for this path, but without a specific test of the difference between the beta weights (e.g. based on multi-group analysis and the chi-square difference test), one cannot assert that a real difference in the beta values exists. Furthermore, even if the paths are statistically significant across two or more country samples, this does not imply that the paths are equivalent. For example, would the results (βChina = 0.47, p < 0.001 versus βCanada = 0.20, p < 0.05) reported in Cheng and Ng (2006) for the path between subjective norm and intention differ across the two countries? A formal test of the difference in beta weights is required. In particular, qualitative comments suggesting that the beta weight for the Chinese sample is ‘larger’ are not appropriate.

In order to overcome the lack of formal statistical testing reported in the articles reviewed, the authors carried out tests where data (e.g. correlations) were available and where tests of some form to assess cross-country differences had not been reported. As a result, cross-country tests are reported in the last column of Table 2 for seven articles. Of the 31 tests undertaken, 16 were statistically significant (up to 10% level). Further, just over half of the cross-country tests conducted for both the attitude–intention and the subjective norm–intention paths showed significant differences (6 out of 11) while for the perceived behavioural control–intention relationship four out of nine were significant. These tests confirm that the TPB interrelationships can vary across countries, but it remains unanswered from these tests whether or not systematic cross-country variations exist that can be explained by cultural or other country-level factors.

The explanatory power of the TRA/TPB for intention across countries is reported in most studies showing a large spread of values (see Table 2 for specific studies). For example, Olsen et al. (2010) reported consistent low effect sizes (R2 ≤ 0.20), whereas Saba et al. (2008) reported consistently high effect sizes (R2 adjusted > 0.75). On average, the TRA/TPB accounted for 50 per cent (61% among the augmented models; 41% in the non-augmented models) of the variance in intention and 41 per cent of the variance in behaviour respectively, which compares favourably against Armitage and Conner's (2001) benchmarks of 39 per cent for intention and 27 per cent for behaviour for the non-augmented TPB model. A number of the articles reported medium to high effect sizes but generally there was no consistent evidence of within study differences in the R2 values observed when contrasting Western (European or US) samples against Eastern (i.e. Asian) samples. For instance, Muk (2007; 2012) reported marginally higher effect sizes (for intention) for Korea and Taiwan than the US, and Pavlou and Chai (2002) reported R2 = 0.33 (for intention) for the US sample and 0.77 for the Chinese sample, whereas Malhotra and McCort (2001) also examining variance in intention reported the opposite with high R2 value (0.66) for the US sample as against a low R2 value (0.21) for the Chinese (Hong Kong) sample. These mixed findings therefore suggest that differences in the explanatory power of the TRA/TPB across countries cannot necessarily be explained by country-level factors.

Testing the role of culture within the theory of reasoned action/theory of planned behaviour model

To assess the five propositions, HLM analyses were conducted based on the 67 attitude–intention correlations, the 67 subjective norm–intention correlations and the 52 perceived behavioural control–intention correlations as reported earlier. The first step assessed whether or not there is significant variation in the size of the correlations between intention and each of its antecedents (attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control). If no significant variation is found this implies that there are no country differences and the conclusion can be drawn that culture does not impact on the relationship(s) within the TPB model. If however, there is significant variation to be explained, the next step is to test the propositions posed. Given that the correlation between individualism and power distance is strong (r = −0.75, p < 0.001) for the set of countries under investigation, separate tests of the propositions were undertaken whereby each Hofstede dimension was analysed individually for each TPB relationship. Dummy variables representing articles were included in all analyses.

The initial assessment of variance components showed that the correlations between intention and both attitude and perceived behavioural control did not differ across the countries (p's > 0.50). Thus, no evidence was found to indicate that the relationships between attitude–intention and perceived behavioural control–intention differed systematically across cultures. On the other hand, evidence of significant (p < 0.01) cross-country variation was found in the subjective norm–intention relationship. As a result, propositions 2 and 4 can be assessed but 1 and 3 cannot. Testing propositions 2 and 4 in two separate HLM analyses revealed support for proposition 4, such that power distance explained systematic differences in the subjective norm–intention relationship (B = 0.003, SE = 0.002, t = 1.99, p < 0.10, two-tail) with a stronger correlation evident in countries high in power distance. Furthermore, an examination of the variation component showed that power distance adequately explains the cross-country variation in the subjective norm–intention relationship with no further cross-country variation left to be explained (p > 0.05). Regarding proposition 2, the results showed that individualism did not explain variation in the subjective norm–intention relationship (p > 0.2) and thus proposition 2 failed to gain support. Overall, these HLM results suggest that cultural differences only affect the relationship between subjective norm and intention and that power distance is an important and sufficient cultural dimension to explain the cross-country variation found.

Discussion and Recommendations

This review has evidenced cross-country differences in the TRA/TPB model relationships. Principally regarding the relationship between subjective norm and intention whereby countries high in power distance (e.g. China, Saudi Arabia and Iraq) have a stronger association between subjective norm and intention. The systematic assessment of cultural differences using multilevel analysis methods overcame the limitations of the studies reported regarding their ability to provide a testable rationale in explaining the observed variations across the country samples studied. One reason for this failure lies in the small number of countries being assessed in the articles reviewed. This limitation is further compounded in the articles reviewed by the lack of specific and well-argued cross-country hypotheses offered as well as the lack of invariance testing.

Nonetheless, the review findings do highlight some variation in the influence of attitude and perceived behavioural control on intention across countries and contexts. However, few articles made predictions regarding differences in the attitude–intention and perceived behavioural control–intention relationships. Of these, the consensus was that no variation was expected across country samples. This view is partially supported by this review as no systematic variation was evident for either of these relationships. Thus, although differences across countries in these relationships do occur, overall they may not vary consistently or with enough magnitude to conclude that cultural differences played a part. However, the lack of statistical evidence may be attributable to the small sample size at the country level (n = 16 or 17) in the country-level regression within the HLM analysis.

On the other hand, the impact of subjective norm on intention is found to vary significantly across countries in this review. A number of studies (e.g. Bagozzi et al., 2000; Chan and Lau, 2002; Jin et al., 2012; Pavlou and Chai, 2002) formulated specific hypotheses for the subjective norm–intention relationship drawing on Hofstede's (1980) individualism dimension. The hypotheses in these studies proposed that the role of subjective norm on intentions would be stronger in collectivistic or interdependent cultures; however, the role of power distance as a moderator was not explored. Therefore, the findings from this review agree with Maheswaran and Shavitt's (2001) observation that cross-country research is still too focused on one of Hofstede's cultural dimensions (individualism–collectivism) as our multilevel results show that power distance rather than individualism explains systematic differences in the subjective norm–intention relationship. The results from a meta-analysis (Manning, 2009) examining the role of norms within the TPB found that descriptive norm (perceived prevalence of the behaviour) and injunctive norm (perceived peer approval/disapproval) are conceptually different and as a result both measures should be modelled within the TRA/TPB. Therefore, although the findings of this review highlight differences in the impact of norms across countries, there is a need for future research to capture and model both normative components in order to provide further insight into the cross-country consistency of the effects of these normative elements. Further, researchers need to go beyond individualism–collectivism and explore Hofstede's other cultural dimensions as well as other cultural frameworks such as Schwartz's (2006) cultural values when forming their hypotheses. Drawing together the results of the review, it can be concluded that the TRA/TPB operates differently across countries and as a result researchers need to take into account the country of study when discussing the findings from their studies. Thus, although an etic approach may be adopted in the collection and analysis of cross-country data, an emic approach to the interpretation of the results should take national culture into account and potentially provide a richer theoretical understanding of the role of culture within the TRA/TPB. A caveat to our research, however, is that it cannot be ruled out that the country-level differences identified are not due to factors other than Hofstede's dimensions (e.g. other cultural values, study variations and methods of data collection), and hence, future research should control for a wider range of factors that could impact on how the TPB operates across studies.

Maheswaran and Shavitt (2001) recognize that there is not enough attention paid to societies with a rich cultural heritage such as Latin America, Africa and the Middle East—a view that is evidenced herein. Thus, future studies should consider applying the model in these societies. TRA/TPB studies across a greater diversity of cultures would enable a stronger assessment of whether the TRA/TPB is indeed influenced by cultural factors.

Related to the above is the importance of using a large number of countries in cross-country studies. Franke and Richey (2010) recommend the use of seven to ten countries to explore cross-national phenomena. However, it should be noted that comparing Eastern and Western cultures using one Eastern country and six Western countries would not suffice in order to achieve a balance of cultural influences. Many of the reviewed studies examined only two countries on the basis of differences in Hofstede's individualism/collectivism scores. As influences on people's behaviours in these countries are likely to differ for other cultural (e.g. power distance, egalitarianism versus hierarchy) or contextual reasons (e.g. economic factors, market structures and maturity), one way around this would be to examine two or more highly individualistic countries and two or more countries with low individualism scores. This would provide reassurance that the likelihood of other cultural or contextual factors affecting the validity of the results is reduced. However, to be able to confidently assert that a particular cultural factor has an impact on the TRA/TPB components or interrelationships, the authors recommend that multiple (around 30 or more) countries with a wide cultural variation should be examined with multilevel analysis employed to assess the country-level (cultural) causal effect. The large number (n > 30) of country samples is needed in order to allow a valid examination of the country-level regression model within the multilevel analysis.

A further recommendation is that future studies should include a clear rationale explaining why the particular set of countries has been selected, as this is critical for theory development. The rationale should then lead to specific hypotheses formulated at the country level as results obtained at an individual level may not necessarily be valid at the country-level (Tsui et al., 2007). Lastly, researchers must conclude on the country-level hypotheses in a rigorous manner, namely based on sound statistical reasoning. Qualitative comments contrasting the observed size of scale means, path/regression coefficients or R2 values are anecdotal at best and can often be misleading. Thus, formal statistical tests such as chi-square difference test (e.g. Olsen et al., 2008), Chow test, or moderated regression followed by simple slope analysis (e.g. Yun and Park, 2010) are necessary to draw valid conclusions on the specific hypotheses posed. Although our research examines the operalization of the TRA/TPB at the country-level, further research is needed to also examine within-country or subcultural differences, which would also likely impact the application of the TRA/TPB. Finally, our review is limited given the small number of countries (17) examined across the 29 articles reviewed. In particular, multilevel analysis with only 17 countries as level-2 units offers limited opportunity to evidence significant results. This had led to our inability to assess two of our propositions. With the increase in the reporting of cross-country TRA/TPB studies, future reviews should be able to examine more articles and country samples.

In light of increasing global marketing practices, these findings have important practical implications for global marketing managers in understanding drivers of consumer behaviour and when framing marketing messages across countries. Marketing managers should bear in mind that in high power distance countries (e.g. China, Saudi Arabia and Iraq), the impact of subjective norm on behavioural intention is stronger thus marketing messages incorporating references to societal norms in these countries would likely be more effective in persuading consumers to engage in behaviours. Lastly, although the multilevel analysis failed to evidence systematic cross-country variation in the attitude–intention and perceived behavioural control–intention relationships, this review has nevertheless identified some evidence of cross-country variations in these relationships. Thus, cross-country marketing campaigns need to take these variations into account in considering the adoption of a standardized marketing approach.

Biographies

Dr Louise Hassan is a reader in managerial studies at Bangor Business School. Her research interests and activities are international in nature. Dr Hassan's work has appeared in journals such as the Journal of Advertising, Journal of Business Research, Journal of Consumer Affairs, Psychology and Marketing, International Marketing Review and the European Journal of Marketing.

Prof. Edward Shiu was appointed to his present position in Bangor Business School in January 2011. Prior to joining Bangor, he was senior lecturer and director of the MSc in International Marketing programme at Strathclyde Business School in Glasgow. He published in a range of journals including the European Journal of Marketing, International Marketing Review, Journal of Business Research and the Journal of Marketing Management.

Dr Sara Parry is a lecturer in marketing at Bangor University, Wales, UK. Her research interests include small and medium enterprise marketing, relationship marketing and the marketing of technologies. She has published in a wide range of journals including the Journal of Marketing Management, Journal of Consumer Behaviour, Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development and the International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research.