Pylorus-preserving versus Pylorus-resecting: Impact on dynamic changes of nutrition and body composition in pancreatic cancer patients before and after pancreatoduodenectomy

Abstract

Objectives

To investigate if different methods of pancreatoduodenectomy (with or without pyloric preservation) would have different impacts on postoperative nutrition and body composition changes among pancreatic cancer patients.

Methods

Demographic and clinicopathological data, perioperative data were collected, body composition (e.g. skeletal muscle cross-sectional area [CSA], visceral fat area [VFA]) were evaluated with abdominal CT before and after surgery. Sarcopenia patients' proportion changes were also recorded.

Results

The hospital stay in the PRPD group was significantly less than that in the PPPD group (p < 0.05). A significant difference was found in CSA, skeletal muscle index (SMI), VFA, VFA/CSA and albumin (ALB) in both groups between preoperative, 3, and 12 months after surgery. The loss of visceral fat in the PRPD group was more prominent than that in the PPPD group at 3 months and 12 months after surgery (p < 0.05). VFA/CSA was higher in the PPPD group than in the PRPD group (3 months: p < 0.05, 12 months: p < 0.001). The proportion of sarcopenic patients increased significantly over time in the PPPD and PRPD groups (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Postoperative CSA and VFA continued to significantly decrease in both PPPD and PRPD groups, while the incidence of sarcopenia continued to increase. Compared with PRPD, PPPD has a protective effect on visceral fat. PPPD may contribute to better maintaining visceral fat mass and blood ALB levels. CT quantification can be an objective and effective method to evaluate the nutritional status of pancreatic cancer patients during the pre- and postoperative period and can provide a useful objective basis for guiding clinical treatment.

1 INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most fatal malignant tumors and is the fourth most common cause of death due to cancer worldwide. Mortality is always high in developed countries, in recent years, China has a similar disease spectrum to developed countries due to lifestyle changes such as consumption of high-calorie foods, smoking, and reduced physical activity.1 Pancreatic cancer ranks high in morbidity and mortality among malignant tumors in China.2 Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) offers the only curative option for pancreatic cancer patients with resectable lesions. Pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy (PPPD) and pylorus-resecting pancreatoduodenectomy (PRPD) are two widely used stomach-sparing modifications of the classic Whipple procedure.3-5 As the long-term survival for patients who performed PD is poor, while functional and nutritional impairments are common, the postoperative quality of life is paramount.6, 7 Nutritional disorders significantly impair the quality of life for patients after PD. Many patients undergoing PD have experienced weight loss due to chronic malnutrition, cancer cachexia syndrome, malabsorption, or dyspepsia.8-11 It is especially important to assess the changes in body composition after PD, and the prognosis is closely related to the nutritional status of each patient, which is crucial for the postoperative quality of life of the patient.7 Although some studies have suggested that preoperative sarcopenia may indicate a worse prognosis in pancreatic cancer patients undergoing surgery,12, 13 no study has investigated if different methods of PD would have different impacts on postoperative nutrition and body composition changes (such as abdominal muscles, visceral fat) among pancreatic cancer patients. Computed tomography (CT) is a routine follow-up examination of pancreatic cancer patients and one of the most advanced imaging techniques available today, providing a highly accurate estimate of body composition.14, 15 The semi-automatic method can quickly calculate the area of the visceral fat and abdominal muscle, with good repeatability, and it is easy to obtain during the postoperative period. Therefore, we used the data from CT scans to analyze changes in pancreatic cancer patients' body composition before and after surgery and to investigate whether PD with or without pylorus preservation would have an influence on body composition and nutritional status changes in postoperative patients.

2 MATERIALS & METHODS

2.1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We retrospectively analyzed medical records of all adult patients (age > 18 years) who underwent pancreatectomy at Wuhan Union Hospital between January 1, 2013 and May 31, 2019. Patients with pancreatic cancer were included in this study if they had undergone PPPD or PRPD, with available preoperative and postoperative CT scans. Both PPPD and PRPD procedures were suitable for patients with ductal adenocarcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, Vater papillary carcinoma, and duodenal carcinoma, as long as the pylorus and stomach were not involved. In our institution, which procedure to choose depends on the surgical habits of different surgeons. Patients with a follow-up fewer than 12 months, other concurrent surgeries, and other preoperative treatments (e.g., chemotherapy) were excluded. A total of 298 patients were involved in this study.

2.2 Patient characteristics

Patient demographics, including age, gender, body mass index (BMI), height, weight, comorbidities (e.g. cardiovascular or hepatic disease, or diabetes), and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade were recorded at first admission. Laboratory tests such as total lymphocyte count (TLC) and albumin were checked before surgery and during follow-up. Type of operation (PPPD or PRPD) was recorded, pathological data as tumor size, histology type, node and perineural infiltration were recorded as well. Perioperative data and hospital course were also collected, including operating time, blood loss, postoperative stay, delayed gastric emptying (DGE), performed relaparotomy or not, and complication morbidity. Data on whether patients received postoperative chemotherapy were also recorded.

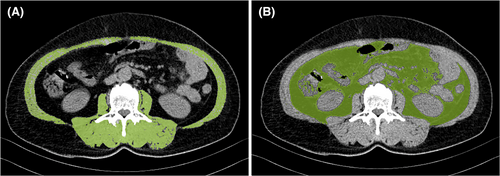

2.3 CT quantification to assess body composition

Data obtained from abdominal CT scans were entered into a semi-automatic volume tool (Syngo Volume tool, Siemens Healthcare) to assess body composition. The patient's baseline abdominal CT (CT0) examination time was within 30 days before surgery (0–30 days, mean 7 days), and the follow-up CT examinations were included as CT1 (short-term): CT examination 3 months after surgery (83–96 days, mean 90.2 days), CT2 (long-term): CT examination 1 year after operation (346–385 days, mean 360 days). Abdominal cross-sectional area (CSA) (cm2) was measured at the level of the third lumbar vertebra, including all muscles bilaterally in this area (internal/external obliques, quadratus lumborum, transversus abdominis, paraspinous, psoas, and rectus abdominis). Muscle density was corrected by using Hounsfield Units (HU) range −29 to 150, visceral fat area (VFA) (cm2) was delineated and obtained on CT by using the adipose tissue threshold (−190 to −130HU) (Figure 1). CSA was adjusted to Skeletal Muscle Index (SMI) by dividing the muscle area by the square of the patient's height, SMI = CSA (cm2)/Height (m2). Sarcopenia was defined: <52.4 cm2/m2 in men and <38.4 cm2/m2 in women.15 All data were collected in a retrospective manner after receiving appropriate approval by the Institutional Review Board.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Quantitative data for statistical variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Variables comparisons were performed by the chi-square test or t-test. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to identify significant differences of mean values before and after operation. Mann–Whitney-U-test was used to identify significant differences of mean values in PPPD and PRPD group. Significance was accepted at the probability level of 0.05. All statistical analyzes were performed using SPSS software version 17.0 (SPSS Inc.).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Patients characters

Comparing the data between the PPPD and PRPD groups (including demographic, clinicopathological data, perioperative data, and hospital course), there was no significant difference in gender, age, body weight, BMI, comorbidity (ex. cardiovascular or hepatic disease, diabetes), histology type, tumor size, positive lymph, and perineural infiltration. The postoperative hospital stay and the incidence of delayed gastric emptying were significantly lower in the PRPD group than those in the PPPD group (p = 0.00519, p = 0.032, respectively). No significant differences were found in operating time, blood loss, relaparotomy, and morbidity between PPPD and PRPD groups. The majority of the patients performed postoperative chemotherapy, no significant difference was found between PPPD and PRPD groups. All of the above results were shown in Table 1.

| Demographic and clinicopathological data | PPPD (131) | PRPD (167) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 61.87 ± 9.01 | 62.35 ± 9.22 | 0.65 |

| Sex | 0.38 | ||

| Male | 97 | 116 | |

| Female | 34 | 51 | |

| Body weight (kg) | 66.2 ± 15.5 | 65.7 ± 16.1 | 0.778 |

| BMI | 23.9 ± 4.8 | 23.8 ± 4.6 | 0.941 |

| Comorbidity | 0.4922 | ||

| Cardiovascular | 26 | 37 | |

| Diabetes | 8 | 11 | |

| Hepatic | 2 | 4 | |

| ASA grade | 0.4233 | ||

| ASA I + II | 79 | 93 | |

| ASA III + IV | 52 | 74 | |

| Tumor size (cm) (mean ± SD) | 2.69 ± 1.1 | 2.67 ± 1.2 | 0.893728 |

| Histology | |||

| Ductal adenocarcinoma | 88 | 111 | 0.8974 |

| Carcinoma papilla | 25 | 38 | 0.4412 |

| Carcinoma distal bile duct | 16 | 17 | 0.5786 |

| Duodenal cancer | 2 | 1 | 0.4258 |

| Nodal positive | 83 | 101 | 0.6117 |

| Perineural infiltration | 30(+)/101 | 36(+)/131 | 0.7816 |

| Perioperative data and hospital course | |||

| Operating time, min (mean ± SD) | 359 ± 44 | 350 ± 46 | 0.068 |

| Blood loss (ml) | 402 ± 77 | 405 ± 78 | 0.849 |

| Postoperative stay (days), (mean ± SD) | 18.4 ± 8.3 | 15.9 ± 6.8 | 0.005199 |

| Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) | 26 (19.8%) | 18 (10.8%) | 0.0328 |

| Relaparotomy | 16 (12%) | 19 (11%) | 0.8238 |

| Complication morbidity | 0.6243 | ||

| Pulmonary | 2 | 1 | |

| Leakage hepaticojejunostomy | 2 | 2 | |

| Leckage Pancreaticojejunostomy | 8 | 13 | |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 0 | 1 | |

| Pancreatitis | 2 | 1 | |

| Wound infection | 1 | 1 | |

| Bleeding | 9 | 8 | |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | 0.493 | ||

| Yes | 103 | 125 | |

| No | 28 | 42 | |

- Note: Significance of bold means p value <0.05.

- Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

3.2 Changes on nutrition and body composition in PPPD & PRPD patients before and after operation

In the PPPD group, a continuous decrease was found in CSA, SMI, VFA, and VFA/CSA, and TLC. Patients' ALB slightly decreased in the 3rd month compared with the preoperative state, with a minimal increase during 3 to 12 months. A significant difference was found in CSA, SMI, VFA, VFA/CSA ALB, and TLC between preoperative and 3 months after surgery, preoperative and 12 months after surgery, 3 months and 12 months after surgery.

In the PRPD group, a continuous decrease was found in CSA, SMI, VFA, VFA/CSA. ALB slightly decreased in the 3rd month compared with preoperative, with a minimal increase during 3 to 12 months. A significant difference was found in CSA, SMI, VFA, VFA/CSA, and ALB in the PRPD group between preoperative and 3 months after surgery, preoperative and 12 months after surgery, 3 months and 12 months after surgery. TLC in the PRPD group increased in the 3rd month after surgery, and decreased close to the preoperative level in the 12th month after surgery. A significant difference was found in TLC between preoperative and 3 months after surgery, 3 months and 12 months after surgery, and no significant difference was found between 12 months after surgery and preoperative.

Our results showed that in PPPD and PRPD groups, both muscle tissue (CSA, SMI), adipose tissue (VFA), and VFA/CSA ratio significantly decreased after surgery within a short period of time (3 months). VFA reduction was very obvious (−36.48 in PPPD and −42.29 in PRPD). In both the PPPD group and PRPD group, albumin decreased significantly in the first 3 months after the operation and increased slightly in the 12th month after the surgery, but it was still lower than the preoperative state. (Table 2).

| CSA | SMI | VFA | VFA/CSA | ALB | TLC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPPD (n = 131) | ||||||

| preOP | ||||||

| Mean | 131.38 | 47.56 | 117.1 | 0.92 | 4.01 | 2.26 |

| SD | 28.27 | 9.27 | 22.9 | 0.25 | 0.45 | 1.55 |

| 3 months postOP | ||||||

| Mean | 124.72 | 45.17 | 80.62 | 0.64 | 3.81 | 2.23 |

| SD | 27.32 | 8.99 | 23.37 | 0.12 | 0.51 | 0.78 |

| 12 months postOP | ||||||

| Mean | 117.5 | 42.54 | 51.18 | 0.43 | 3.85 | 2.17 |

| SD | 27.53 | 9.09 | 19.47 | 0.12 | 0.56 | 0.85 |

| Difference between 3 months postOP and preOP | ||||||

| Mean | −6.66 | −2.39 | −36.48 | −0.28 | −0.2 | −0.03 |

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Difference between 12 months postOP and preOP | ||||||

| Mean | −13.88 | −5.02 | −65.92 | −0.49 | −0.16 | −0.09 |

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Difference between 12 months postOP and 3 months postOP | ||||||

| Mean | −7.22 | −2.63 | −29.44 | −0.21 | 0.04 | −0.06 |

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PRPD (n = 167) | ||||||

| preOP | ||||||

| Mean | 128.93 | 47.11 | 116.3 | 0.93 | 4.04 | 2.08 |

| SD | 25.89 | 7.76 | 20.3 | 0.23 | 0.48 | 0.62 |

| 3 months postOP | ||||||

| Mean | 121.29 | 44.32 | 74.01 | 0.61 | 3.65 | 2.18 |

| SD | 24.48 | 7.64 | 21.52 | 0.11 | 0.37 | 0.56 |

| 12 months postOP | ||||||

| Mean | 115.37 | 42.16 | 45.15 | 0.38 | 3.7 | 2.04 |

| SD | 25.27 | 7.93 | 17.77 | 0.1 | 0.44 | 0.56 |

| Difference between 3 months postOP and preOP | ||||||

| Mean | −7.64 | −2.79 | −42.29 | −0.32 | −0.39 | 0.1 |

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Difference between 12 months postOP and preOP | ||||||

| Mean | −13.56 | −4.95 | −71.15 | −0.55 | −0.34 | −0.04 |

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.606 |

| Difference between 12 months postOP and 3 months postOP | ||||||

| Mean | −5.92 | −2.16 | −28.86 | −0.23 | 0.05 | −0.14 |

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

- Note: Significance of bold means p value <0.05.

- Abbreviations: ALB, albumin; CSA, cross-sectional area; postOP, after operation; PPPD, pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy; preOP, before operation; PRPD, pylorus-resecting pancreatoduodenectomy; SMI, skeletal muscle index; TLC, total lymphocyte count; VFA, visceral fat area.

3.3 Differences in changes on body composition and nutrition between PPPD & PRPD group

With regard to body composition, there was no significant difference in skeletal muscle (CSA, SMI) and visceral fat area (VFA) between PPPD and PRPD groups before operation. Visceral fat was found to be most affected by pancreaticoduodenectomy. The reduction of visceral fat was more prominent in the PRPD group than the PPPD group with statistically significant difference in both 3 and 12 months after surgery (p < 0.05). CSA and SMI showed a continuous decrease at 3 and 12 months after surgery in both PPPD and PRPD groups, although there was no significant difference between the two groups before and after surgery. VFA/CSA, an indicator of sarcopenic obesity, decreased more prominent in the PRPD group than in the PPPD group, with a significant statistical difference (3 months: p < 0.05, 12 months: p < 0.001). (Table 3).

| PPPD (n = 131) | PRPD (n = 167) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSA (cm2) | |||

| preOP | 131.38 ± 28.27 | 128.93 ± 25.89 | 0.443 |

| 3 months postOP | 124.72 ± 27.32 | 121.29 ± 24.48 | 0.249 |

| 12 months postOP | 117.50 ± 27.53 | 115.37 ± 25.27 | 0.493 |

| SMI (cm2/m2) | |||

| preOP | 47.56 ± 9.27 | 47.11 ± 7.76 | 0.651 |

| 3 months postOP | 45.17 ± 8.99 | 44.32 ± 7.64 | 0.388 |

| 12 months postOP | 42.54 ± 9.09 | 42.16 ± 7.93 | 0.704 |

| VFA (cm2) | |||

| preOP | 117.1 ± 22.9 | 116.3 ± 20.3 | 0.753 |

| 3 months postOP | 80.62 ± 23.37 | 74.01 ± 21.52 | 0.013 |

| 12 months postOP | 51.18 ± 19.47 | 45.15 ± 17.77 | 0.006 |

| VFA/CSA | |||

| preOP | 0.92 ± 0.25 | 0.93 ± 0.23 | 0.816 |

| 3 months postOP | 0.64 ± 0.12 | 0.61 ± 0.11 | 0.011 |

| 12 months postOP | 0.43 ± 0.12 | 0.38 ± 0.10 | <0.001 |

| ALB (g/dL) | |||

| preOP | 4.01 ± 0.45 | 4.04 ± 0.48 | 0.640 |

| 3 months postOP | 3.81 ± 0.51 | 3.65 ± 0.37 | 0.004 |

| 12 months postOP | 3.85 ± 0.56 | 3.70 ± 0.44 | 0.012 |

| TLC (109/L) | |||

| preOP | 2.26 ± 1.55 | 2.08 ± 0.62 | 0.195 |

| 3 months postOP | 2.23 ± 0.78 | 2.18 ± 0.56 | 0.550 |

| 12 months postOP | 2.17 ± 0.85 | 2.04 ± 0.56 | 0.133 |

- Note: Significance of bold means p value <0.05.

- Abbreviations: ALB, albumin; CSA, cross-sectional area; postOP, after operation; PPPD, pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy; preOP, before operation; PRPD, pylorus-resecting pancreatoduodenectomy; SMI, skeletal muscle index; TLC, total lymphocyte count; VFA, visceral fat area.

There were significant differences in albumin levels between PPPD and PRPD groups at 3 months and 12 months after surgery, but no difference was found in Albumin levels before operation between PPPD and PRPD groups. There was no significant difference in TLC between the PPPD group and the PRPD group before and after surgery. (Table 3).

3.4 Changes of sarcopenia patients' proportion in PRPD & PPPD patients

Referring to sarcopenia criteria,14 the differences in the proportion of patients with sarcopenia among PPPD and PRPD groups were not statistically significant in the preoperative or postoperative state (Table 4, P1). However, the proportion of patients with sarcopenia in the PPPD and PRPD groups was found to increase over time, and the difference was statistically significant (Table 4, P2). Within 12 months after PD, the proportion of patients with sarcopenia increased to 73% in PPPD and 68% in PRPD, respectively.

| PPPD (n = 131) | PRPD (n = 167) | Total (n = 298) | P1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pre-OP | 48 | (37%) | 51 | (31%) | 99 | (33%) | 0.267 |

| 3 m-postOP | 69 | (53%) | 96 | (57%) | 165 | (55%) | 0.4068 |

| 12 m-postOP | 96 | (73%) | 113 | (68%) | 208 | (70%) | 0.2929 |

| P2 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

- Note: Significance of bold means p value <0.05.

- Abbreviations: postOP, after operation; PPPD, pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy; preOP, before operation; PRPD, pylorus-resecting pancreatoduodenectomy.

4 DISCUSSION

The patients' nutritional status after pancreatoduodenectomy is usually poor. Cachexia, sarcopenia, and obvious weight loss are frequently observed in patients after pancreatoduodenectomy due to malnutrition, postoperative dysfunction, metabolic chaos, chemotherapy toxicity, etc. Several studies have compared the postoperative body composition and nutritional status changes in the PPPD and PRPD groups, but they were based on non-imaging modalities such as laboratory findings, demographic characteristics, or bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA).5, 16, 17 CT or MRI is currently considered the gold standard for quantitative assessment of visceral fat and intra-abdominal muscle.18, 19 As patients after PD will routinely undergo abdominal and pelvic CT scans to detect metastasis or recurrence, CT is the optimal tool for analyzing postoperative body composition changes. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to dynamically compare the changes in patients' body composition before and after pancreatic cancer surgery based on CT quantitative analysis, and to explore the effects of PPPD and PRPD on nutritional status and body composition changes based on nutrition parameters and CT examinations during 12 months after PD.

Consistent with previous studies,7, 20, 21 our research also found no difference between PPPD and PRPD in operating time, perioperative blood loss, relaparotomy and morbidity of complication. The incidence of delayed gastric emptying (DGE) in PPPD patients was higher than that in PRPD patients in our study, which might result in prolonged postoperative nasogastric tube placement time, and pyloric spasms caused by pyloric weaning and denervation after PPPD might be a possible cause.22, 23 Post-operation hospital stay in PRPD was shorter than in PPPD in our study, which might be due to higher DGE incidence in the PPPD group.

Our research found that in terms of body composition, both PRPD and PPPD patients showed significant muscle and abdominal fat loss in the 3rd month after surgery compared with the preoperative state, the same phenomenon existed in the 12th month after surgery, and these above differences were statistically significant. Postoperative wasting,24-26 chemotherapy toxicity,27, 28 delayed gastric emptying,29 etc., will contribute to the loss of muscle and fat in patients after PD, which will be related to poor quality of life. A previous study used BIA to observe the changes in body composition after PD30 and found fatmass continuously decreased after pancreatectomy. Park et al found that although some patients' body weight recovered within 6 months after surgery, their body fat continues to decrease.31 Our research results were consistent with these researches.

We also compared differences in changes in body composition and hematological parameters reflecting nutritional status between the PPPD and PPRD groups. It was found that these indicators (CSA, SMI, TLC) were not different between the two groups. Although the indicators reflecting skeletal muscle changes (CSA, SMI) of the two groups decreased significantly at 3rd and 12th month after surgery, there was no significant difference between PPPD and PPRD groups. Previous studies reported that although BMI change and weight loss were not statistically different between PRPD and PPPD groups, BMI and body weight were significantly lower postoperatively compared to preoperatively in each group.17, 32, 33 However, these studies have not been able to show which and how much body component (muscle or fat) is lost. In our study, VFA decreased more significantly in the PRPD patients than those in the PPPD, which suggested that indicators reflecting visceral fat changes (VFA, VFA/CSA) would be a more independent predictor than indicators reflecting skeletal muscle changes (CSA, SMI) to reflect postoperative body composition changes in pancreatic cancer patients. ALB of PPPD and PRPD groups of patients dropped to the lowest point at the 3rd month after surgery, and recovered slightly at the 12th month. PPPD was better than PRPD in maintaining postoperative ALB levels in this study. Although there were significant differences in ALB levels between the two groups, the ALB levels in both groups were within the normal physiological range. If we only refer to the results of postoperative blood tests, it may not be enough to objectively reflect the true nutritional status of postoperative patients. In contrast, the addition of CT quantification analysis demonstrated superiority in quantifying body composition.

The proportion of patients with sarcopenia after PD showed a continuous increase in 3 months and 12 months. Regardless of the PPPD group or the PRPD group, the proportion of patients with sarcopenia at 3 months and 12 months after the surgery was significantly higher than that before surgery with statistical significance (p < 0.001, Table 4). This finding is similar to previous studies in which sarcopenia was significantly increased after surgery compared to before surgery, suggesting a poorer prognosis and shorter overall survival in cancer patients.34 No significant difference was found in the proportion of patients with sarcopenia between PPPD and PRPD groups regardless of before and after PD in this study. Although sarcopenia is an indicator of overall survival after pancreatic cancer surgery, a recent randomized trial found no difference in overall survival after PPPD and PRPD,17 our study may help explain why the two surgical procedures (PPPD and PRPD) had no effect on patients' overall survival after surgery.

The present study presents some limitations. Firstly, this is a single-center retrospective study, further work is required validation by well-designed, prospective, multicenter studies. Secondly, postoperative chemotherapy may affect appetite and thus nutritional status, but there was no difference in the proportion of patients who received postoperative chemotherapy in our two groups, so this effect can be ignored. Thirdly, our research subjects are only Asians, and different ethnic groups may have different results, which needs to be verified in a wider cross-regional study. Lastly, whether inconsistency in body composition between PPPD and PRPD patients affects overall quality of life and overall survival requires further studies to verify.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this study was based on CT quantitative method to measure the body composition (abdominal muscle and VFA) of patients, so as to dynamically observe the changes in body composition in pancreatic cancer patients within 12 months after surgery. Postoperative CSA and VFA continued to significantly decrease in both PPPD and PRPD groups, while the incidence of sarcopenia continued to increase. However, compared with PRPD, PPPD can contribute to better maintaining visceral fat mass and blood ALB levels. In conclusion, CT quantification can be an objective and effective method to evaluate the nutritional status of pancreatic cancer patients during the pre- and postoperative period and can provide a useful objective basis for guiding the clinical treatment of patients.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Qianna Jin: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing -original draft. Qianqian Ren: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization. Xiaona Chang: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology. Xiaoming Lu: Data curation, Investigation, Writing -review & editing. Guobin Wang: Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Writing -review & editing. Nan He: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing -review & editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We sincerely appreciate the editor and reviewers for their constructive comments. This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82172755) and.

Research Fund of Molecular Imaging Key Laboratory, HuBei province, China (No.02.03.2015-151).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All of the authors do not report relevant conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets used in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.