Why we need neurodiversity in brain and behavioral sciences

Abstract

In this article, we present the case for the adoption of a neurodiversity paradigm as an essential framework within the brain and behavioral sciences. We challenge the deficit-focused medical model by advocating for the recognition of neurocognitive variances—including autism, ADHD, dyslexia, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder—as natural representations of human diversity. We call for a shift in research and practice towards valuing neurodivergent individuals' unique strengths and contributions and promoting inclusivity and empathy. In critiquing the tendency to pathologize cognitive differences, we argue for a re-evaluation of therapeutic goals to reflect a more nuanced understanding of neurodiversity. Highlighting the socio-ethical implications of therapy-focused research, we urge an appreciation of the potential for innovation and problem-solving that neurodivergent individuals bring to society. The conclusion is a call to action for an integrated approach in research, policy, and societal attitudes that affirms neurodiversity, fostering an environment in which all forms of cognitive functioning are celebrated as part of human advancement.

Key points

What is already known about this topic?

-

Neurodiversity is a concept that recognizes the natural variation in human cognition and challenges the deficit-oriented view of neurodevelopmental differences. The neurodiversity movement advocates for a shift in perspective, from pathologizing cognitive differences to embracing them as integral to human diversity. Research has begun to explore the implications of neurodiversity in various fields, including psychology, education, and the workplace.

What does this study add?

-

This perspective article calls for a paradigm shift in neuroscientific research and practice by critically engaging with current therapeutic modalities. It emphasizes the need to integrate neurodiversity as a cornerstone of cognitive science. It proposes a future in which research methodologies and societal norms are recalibrated to recognize neurodivergent individuals as valuable contributors rather than subjects for normalization, promoting a more inclusive understanding of human cognition.

1 INTRODUCTION

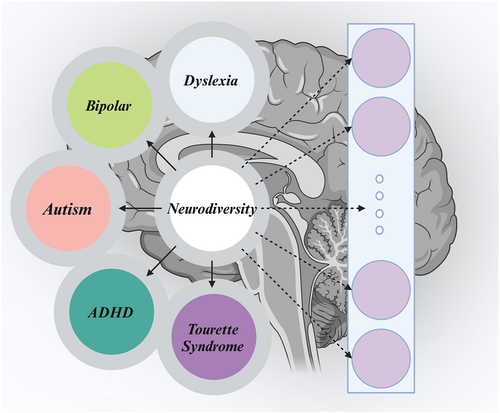

Neurodiversity, a term that has gained significant traction in recent years, refers to the inherent and boundless variation in neurocognitive functioning within the human species.1 This paradigm-shifting concept challenges the notion of a singular, archetypal ‘normal’ or ‘healthy’ brain or mind, instead embracing the full spectrum of cognitive abilities and differences as natural expressions of human diversity.2 Initially coined within the autism community in the 1990s, the concept of neurodiversity has since broadened in scope to encompass a wide array of neurocognitive variances, including but not limited to ADHD, dyslexia, and Tourette syndrome, as illustrated in Figure 1. Rooted in the pioneering work of autistic sociologist Judy Singer and Kassiane Asasumasu, and further expanded upon by scholars such as Martijn Dekker, the neurodiversity paradigm advocates for a fundamental shift in the way cognitive differences are conceptualized and valued in society and science.3, 4

Neurodiversity: A Visual Representation of Dyslexia, Bipolar Disorder, Autism, ADHD, Tourette Syndrome, and Other Neurodivergence. The purple nodes signify the broad inclusivity of neurodiversity, encompassing a wide range of human neurological experiences beyond medically identified conditions.

As a multifaceted construct encompassing biological, psychological, and social dimensions, the neurodiversity paradigm challenges the traditional deficit-oriented discourse. The existing approach frames neurocognitive differences primarily in terms of impairments, deficits, and disorders requiring intervention or correction. By recognizing the complex interplay of factors that shape an individual's neurocognitive profile, this framework instead promotes a more holistic and strengths-based understanding of cognitive differences. It posits that neurocognitive variance is not merely a subject of medical interest but a reflection of the natural diversity of human brain function; this is supported by empirical studies from certain perspectives.5

This perspective article aims to catalyze a paradigm shift in neuroscientific research and practice towards critical engagement with current therapeutic modalities and to underscore the necessity of embracing and integrating neurodiversity as a cornerstone of cognitive science. It envisions a future where research methodologies and societal norms are recalibrated to recognize neurodivergent individuals as integral contributors to the human tapestry rather than subjects for normalization. This reframing is not merely academic but a call to action for embracing cognitive plurality as a fundamental aspect of human advancement and societal enrichment.

2 THERAPY-ORIENTED MEDICINE AND THE NEURODIVERSITY PARADIGM

The progress of neuroscience research aimed at developing therapies for conditions such as autism, ADHD, bipolar disorder, and dyslexia has undoubtedly enhanced our understanding of and ability to treat such disorders. However, an uncritical embrace of these therapy-oriented achievements risks reinforcing the notion that neurodivergence requires correction, an idea rooted in a neurotypical bias. This bias can inadvertently pathologize natural variations in brain functioning, presenting them as deviations from a 'norm' rather than acknowledging a spectrum of neurological diversity.

For example, while the discovery of the KDM5A gene's role in autism by EI Hayek et al. expands our knowledge,6 it also raises questions about the end goals of such research—are we seeking to 'fix' individuals to fit a neurotypical mold, or to broaden our societal understanding and acceptance? Similarly, genetic links between ADHD and the immune system established by Fontana et al. could help develop medical interventions; however, these interventions may overlook the strengths and contributions of those with ADHD.7 Transcranial magnetic stimulation for bipolar disorder, as researched by Levenberg and Cordner,8 and the 'Multitudes' digital assessment tool for dyslexia developed by UCSF in 2022 represent significant strides in their respective interventions. Yet, they also exemplify the medical model's tendency to view neurodivergent conditions as problems in need of solutions. We are not arguing to convict therapy-oriented epistemology but to urge a re-examination of the epistemological basis of research such as that illustrated above.

It is important to acknowledge that the deficit-focused medical model stems not only from neurological differences but also from the suffering experienced by neurodivergent individuals. For instance, psychiatric "patients" suffer an increased risk of self-harm as well as suicide.9 This highlights the merits of the conventional approach in addressing the challenges faced by these individuals. However, it is crucial to strike a balance between providing necessary support and intervention while also embracing natural variation in human cognition and behavior. Although these studies offer new avenues for early detection and intervention of deviations from a given norm, it is crucial to ask who defines that norm. Is the ultimate aim to integrate neurodiverse individuals into society as they are, or to conform them to a narrow definition of normalcy? As we move forward, the field of neuroscience and society at large must adopt a truly inclusive approach that regards neurodiversity not as a minority or majority issue but as an integral part of the human experience.

3 SOCIO-ETHICAL CONSIDERATION UNDER NEURODIVERGENT LENS

Importantly, beyond their clinical application, studies of this type have significant socio-ethical implications. This can be exemplified in medical research. A study on ARID1B gene mutations in ASD provided compelling evidence of how specific gene-level modifications can lead to varied cellular changes in brain organoids.10 This raises critical questions about the predictability and safety of proposed targeted genetic interventions. Given that the modifications affect complex cellular processes, the probability of even precise changes translating into predictable trait alterations in individuals with ASD remains uncertain. The inherent diversity of the autism spectrum means that what may be beneficial for some may not be for others, and a change that addresses one trait could inadvertently affect another. But from a social perspective, we should step back further to think about whether the changes should even be made at all.

The ethical implications of such gene modification are profound from a societal perspective. If neurodiversity, including the range of traits seen in ASD, is a natural and valuable expression of human diversity, then interventions aimed at normalizing these traits to fit a neurotypical standard must be approached with caution. The potential for unintended side effects11 —both at the cellular level and in broader cognitive and behavioral terms—is not just a medical concern but a societal one. We must consider whether the pursuit of genetic modification to alter ASD traits respects the individuality of neurodiverse people or seeks to conform them to a narrowly defined standard; more specifically, we must interrogate the very basis of a standard of normalcy on which we judge which parts of an individual should be altered or accepted. Finally, we must question whether it is ethically appropriate to even attempt the decision to change the personal traits of an individual.

In this light, every therapeutic advancement should be weighed not only on its medical efficacy but also on its alignment with the principles of neurodiversity. This involves critically examining whether our approaches inadvertently perpetuate a view of neurodivergence as a deficit rather than a distinct and valid form of human neurocognitive functioning. Such introspection and recalibration of our research methodologies and therapeutic goals are crucial. They will ensure that while we pursue scientific progress and beneficial treatments, we simultaneously honor and preserve the richness of neurocognitive diversity. This in turn will allow us to foster a more inclusive and empathetic understanding of the myriad ways in which human brains can function and thrive.

It should be noted that our provocation aims to epistemologically complement the therapeutic approach to research. We urge different ways of perceiving and researching neurocognitive conditions in the hope of opening novel avenues of investigation and innovation. Our endeavor is not a lonely island but echoes a widespread shift in the fields of neuroscience and medicine; this is evidenced by the current interdisciplinary call for papers on the value of neurodiversity from 38 academic journals, including the International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience, the European Journal of Neuroscience, and Developmental Neurobiology among others.12 To further demonstrate the importance of our perspective, we will present some empirical cases which challenge the “ontological certainty” assumed by the neurotypical perspective, and illuminate the often-unrecognized strengths of the neurominority.

4 CONFRONTING NEUROTYPICAL BIAS IN RESEARCH DESIGN

To elucidate our position, we must address the concept of cognitive bias, as exemplified by our previous examples. This phenomenon stems from the brain's tendency to filter information through the prism of personal experience and preference.13 Such mental heuristics allow for rapid processing of the potentially overwhelming influx of sensory inputs and cognitive demands by prioritizing consistent patterns or expectations. However, this becomes problematic when it informs the framework of research, particularly in the context of neurodiversity. The resultant 'neurotypical bias' occludes the spectrum of neurological experiences, skewing research towards a homogenous perspective.

In neurodiversity studies, traditional behavioral research paradigms may fail to incorporate the varied internal experiences of neurodiverse individuals.14 As these paradigms are routinely based on the experiences of neurotypical subjects, they may inadvertently marginalize those of neurodiverse populations. To help researchers step into neurodivergent shoes to promote more inclusive study design, we will illustrate research into inner speech—a cognitive function presumed to be ubiquitous—drawing arguments from Alderson-Day and Fernyhough and Alderson-Day and Pearson.15, 16

Inner speech is the experience of talking to oneself in one's mind. It is a silent form of speech that only the individual can hear, which often involves words or short phrases that can help in organizing thoughts, problem-solving, self-reflection, or planning. Inner speech is integral to our conceptions of memory, development, and interpersonal communication.15 However, as Alderson-Day and Pearson16 point out, this may not be as universal as neurotypical researchers might expect, particularly within neurominority groups. For instance, some autistic individuals may not predominantly employ inner speech to interact with the world, preferring instead visual or other sensory-driven modalities.17 Empirical evidence, including anecdotal and autobiographical accounts alongside research by Hurlbut et al. 18 Soulières et al. 19 and Sahyoun et al. 20 indicates a pronounced visual, rather than verbal, internal processing preference among many autistic individuals.15 In contrast, several studies have observed a more pronounced use of inner speech in ADHD children than in their neurotypical counterparts. Schizophrenic people present a further different mode of inner speech, in the form of auditory verbal hallucinations, hearing voices in the absence of any speaker. At the same time, observations of no difference between neurodiverse and neurotypical groups have also been made. These findings are corroborated by neuroimaging studies within those demographics.19, 20 With the example of inner speech, we can see the value for neurotypical researchers to consider neurodivergent groups when conducting relevant research. We should also realize that a one-size-fits-all approach should always be avoided in the context of human neurodivergence. A central focus of our call to action involves further attempts to promote mutual understanding and establish this as a basis for research ethics.

5 ARE NEUROMINORITIES DISADVANTAGED?

In advocating for a shift towards research through a neurodiverse lens, we must highlight a critical oversight: the tendency of brain-related studies to predominantly focus on the challenges faced by neurominority groups, while neglecting the unique advantages these individuals may possess. These attributes, while present across the general population, often manifest more intensely within neurodivergent groups. It is essential to recognize that in the spectrum of neurodivergence, there exist points where attributes considered advantageous can be as prevalent as those deemed challenging. Neurominority groups often exhibit a remarkable range of behaviors and cognitive abilities that, although under-researched within brain science, have the potential to significantly contribute to individual success and quality of life. If studied with as much rigor and interest as the difficulties, these exceptional traits could offer a more balanced and comprehensive understanding of neurodiversity. Ultimately, this would promote a more inclusive view of cognitive function and its impact on human accomplishment.

One such strength is 'hyperfocus,' a term referring to the ability of people, particularly those with ADHD, ASD, and schizophrenia, to concentrate intensely on tasks that deeply interest them. This contrasts with the common emphasis on their challenges with mundane tasks that fail to engage their attention.21 Hyperfocus is not simply about being absorbed in a task; it varies in presentation depending on the situation, the individual's motivation, and their daily life experiences.22 While also associated with challenging outcomes—including difficulty in managing emotions and links to mood disorders23—it is a dynamic ability that can lead to remarkable productivity; its occurrence and neurological manifestations in neurominority groups are worthy of further study.

Children with ADHD often exhibit 'risk-taking behavior', meaning they are more inclined to engage in activities that involve uncertainty or potential danger.24 This trait can be advantageous during developmental stages, encouraging exploration and learning. When parents have a good understanding of their child's neurological needs and provide the right support, this risk-taking can be positively guided.25 Unfortunately, the risk-taking behavior among ADHD and ASD children also attracts negative attention, resulting in less rather than more understanding of children's needs from a neurological perspective.

The brain processes underlying behaviors such as hyperfocus and risk-taking are not well-researched. This is partly because these traits exist in a spectrum and are present to varying degrees in all individuals, not just those with neurological differences. However, neurominority groups are often erroneously viewed through a deficit-centered lens, which leads to a failure to recognize the unique balance of strengths and challenges that characterize their cognitive processing and functioning. Overall, this results in a biased and incomplete understanding of their experiences and abilities. This lack of research is even more pronounced for less common conditions, such as Tourette Syndrome, where 'exceptional creativity'26—the ability to think in novel and inventive ways—is a notable but under-investigated characteristic.

6 CONCLUSION: A CRITICAL AND ACTIONABLE PATH FORWARD FOR EMBRACING NEURODIVERSITY

As we conclude our exploration into the importance of embracing neurodiversity within the realms of brain and behavioral sciences, it is clear that the journey ahead is complex but essential. The neurodiversity paradigm challenges the traditional deficit-oriented medical model, advocating for a shift in perspective that recognizes neurodivergent individuals as integral contributors to human diversity rather than subjects for normalization.

6.1 Implications for future research and practice

In the future, researchers must critically examine inherent biases and develop subsequent methodologies that are genuinely inclusive of neurodivergent perspectives. This involves acknowledging the unique strengths and abilities of neurodivergent individuals and integrating these insights into our collective understanding of cognitive and behavioral sciences. As Fletcher-Watson and Happé27 emphasize, participatory research designs that involve neurodivergent individuals in the research process are crucial to ensure that studies reflect their lived experiences and priorities. By actively engaging neurodivergent individuals as co-researchers and collaborators, we can generate more accurate, relevant, and ultimately meaningful findings that truly capture the essence of neurodiversity.

Bourke28 reflects on the importance of participation, method, and power in participatory research in health, emphasizing the need to consider power dynamics and ensure that participants have a meaningful role in shaping the research process. This is particularly relevant in the context of neurodiversity research, where historically, neurodivergent individuals have been excluded from the research process or treated as passive subjects rather than active collaborators. Fletcher-Watson et al29 build upon this idea by discussing inclusive practices for neurodevelopmental research, including community-based participatory research (CBPR). They highlight the importance of partnerships with groups that are convened and led by community members, such as neurodivergent individuals; examples of successful participatory research projects include working with autistic young people in a CBPR framework to study mental health experiences. Gourdon-Kanhukamwe et al30 further expand on the potential of such methods by calling for a combination of participatory research and open science practices to advance neurodiversity research. They argue that this combination can strengthen the relationship between the public and scientific communities, empower neurodivergent people, and ensure that current research is meaningful and relevant to the neurodivergent community. By embracing open science practices, such as sharing research data, materials, and findings in accessible formats, researchers can promote transparency, collaboration, and inclusivity in neurodiversity research. However, we also acknowledge the challenges of implementing participatory research, such as the need for more open science resources and training in neurodiversity research.

In addition to participatory research practices and open science, future research must also re-evaluate therapeutic goals and interventions to align with a strengths-based approach. Instead of aiming to “normalize” neurodivergent individuals, the focus should shift towards supporting them in ways that enhance their well-being and enable them to leverage their unique strengths. This involves developing targeted interventions and accommodations that celebrate and nurture the diverse abilities of neurodivergent individuals, empowering them to thrive in their personal and professional lives. By adopting a strengths-based approach, researchers and practitioners can move away from a deficit-based perspective and instead focus on the inherent value and potential of neurodiversity.

Furthermore, the growing body of neurodiversity literature must also explore the inherent value of diversity in cognitive processing for its own sake. While research on 'general' cognition among the assumed typical populace is often driven by curiosity and the desire to expand our knowledge, research on neurodivergent cognition frequently focuses on addressing impairments or making comparisons to neurotypical populations. However, by adopting a curiosity-driven lens, we can create a science that celebrates and learns from neurodiversity without the need for constant comparison or pathologization. This approach recognizes the inherent worth in appreciating the full spectrum of human cognitive processing and functioning, enriching our collective understanding of the diversity within our species. By shifting the focus from a deficit-based perspective to an exploration driven by genuine interest and appreciation, we can foster a more inclusive and affirming narrative surrounding neurodiversity.

6.2 Societal benefits of embracing neurodiversity in scientific research

The adoption of neurodiversity-inclusive practices in scientific studies offers significant societal benefits. By valuing the full spectrum of neurocognitive functioning, we can foster a more inclusive and innovative society. Neurodivergent individuals often bring unique problem-solving skills and innovative thinking to the table, which could lead to breakthroughs in specialized fields.31 In the workplace, embracing neurodiversity can lead to a more diverse and skilled workforce, as seen in programs implemented by companies like Microsoft and SAP, resulting in a broader range of skills within their teams and increased productivity.32 Understanding and valuing neurodiversity also promotes empathy and social cohesion, reducing social isolation for neurodivergent individuals and building stronger and more supportive communities. In education, embracing neurodiversity can lead to more personalized and effective learning strategies, improving educational outcomes for all students.33 Additionally, a neurodiversity-affirming approach in scientific research can contribute to the overall health and well-being of neurodivergent individuals, improving mental health outcomes and quality of life.34

6.3 A call to action

In conclusion, the collective mission of researchers, practitioners, policymakers, and engaged citizens is to forge an ever-more inclusive society. This imperative calls for the endorsement of policies that empower neurodivergent individuals and the dismantling of existing barriers that marginalize neurocognitive diversity. While the critiques of Singer35 underscore the complexity of these efforts advocating for a nuanced appreciation of neurodivergent experiences, they do not diminish the transformative potential of the neurodiversity movement. For brain scientists, the path ahead is rich with the promise of discovery—each finding a thread in the broader tapestry of human cognition. Our commitment to exploring the neurological underpinnings of neurodiversity not only advances scientific understanding but also fosters innovative interventions tailored to diverse neurological profiles. By translating our research into actionable insights, we can influence policy, promote educational and occupational inclusivity, and drive societal change. It is our unique privilege to chart the unexplored territories of the brain, to uncover the strengths that lie in cognitive differences, and to advocate for an environment where every neurodivergent individual can thrive. As we contribute to this journey, let us reinforce our resolve to celebrate the intricate variations of the human mind, and in doing so, cultivate a more equitable, empathetic, and enlightened future. This, we believe, is not merely an academic or scientific endeavor but a profoundly moral one, wherein our greatest triumph lies in the affirmation of neurocognitive diversity as a cornerstone of human innovation and communal strength.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Yinghui Xia: Conceptualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing. Peng Wang: Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing. Jonathan Vincent: Project administration; Supervision; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was financially supported by the China Scholarship Council (202208060121).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this study.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethics approval was not needed in this study.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.