Dinitrogen Activation with Low-Valent Strontium

Dedicated to Professor Rudi van Eldik on the occasion of his 80th birthday

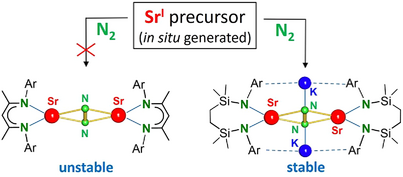

Graphical Abstract

Abstract

DFT calculations on β-diketiminate (BDI) complexes with the full series of alkaline-earth (Ae) metals show that (BDI)AeAe(BDI) complexes of the heavier Ae metals (Ca, Sr, Ba) have long weak Ae─Ae bonds that are prone to homolytic bond cleavage. However, isolation of (BDI)Sr(μ-N2)Sr(BDI) with a side-on bridging N22− dianion should thermodynamically be feasible. Attempts to stabilize such a complex with the super bulky BDI* ligand failed (BDI* = HC[(Me)C = N-DIPeP]2, DIPeP = 2,6-Et2CH-phenyl). First, N2 fixation with a Sr complex was enabled by a heterobimetallic approach. Reduction of (DIPePNN)Sr with potassium gave (DIPePNN)2Sr2K2(N2) (6-Sr); DIPePNN = DIPePN-Si(Me)2CH2CH2Si(Me)2-NDIPeP. A similar Ca product was also isolated (6-Ca). Crystal structures reveal a N22− anion with side-on bonding to Ae2+ and end-on coordination to K+. DFT calculations and Atoms-In-Molecules analyses show mainly ionic bonding. Both 6-Ae complexes are synthons for hitherto unknown (BDI*)AeAe(BDI*) (Ae = Ca, Sr) and react by releasing N2 and two electrons. Although surprisingly stable in benzene, the reduction of I2 and H2 is facile. Fast reaction with Teflon led to formation of crystalline [(DIPePNN)SrKF]2 (7), which is labile and decomposed to KF and (DIPePNN)Sr. Latter reactivity underscores potential use of 6-Ae complexes as very strong, hydrocarbon-soluble reducing agents.

Introduction

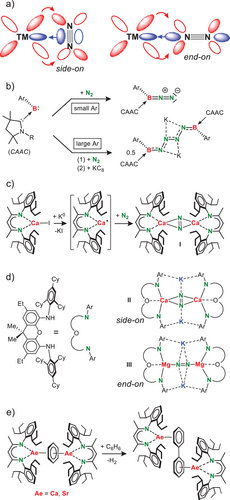

Activation and cleavage of the dinitrogen N≡N triple bond, one of the strongest known chemical bonds, is an important step toward the syntheses of N-containing commodity chemicals.[1] This major challenge can generally be achieved by use of transition metals which can activate N2 by synergistic donor–acceptor bonding, either in side-on or end-on fashion (Scheme 1a). The conversion of N2 to NH3 by Haber–Bosch catalysis is worldwide one of the largest bulk processes. Due to enormous demand and harsh reaction conditions (400 °C–600 °C, 200–400 bar), this process requires nearly 2% of the world-wide energy consumption.[1] Modern investigations focus on N2 fixation under mild, homogeneous conditions by precise catalyst design. [2-5]

Although this work is traditionally based on N2 activation with transition metals, quite some progress has been made with lanthanide metal complexes.[6] Most recently, it was shown that even s- and p-block (semi-)metals are able to activate N2.[7, 8] The Braunschweig group activated N2 at a B center (Scheme 1b),[9] showing that d-orbital participation is not a strict requirement. Later work by Mézailles and coworkers demonstrated N2→NH3 conversion with in situ generated B-centered radicals.[10] Aiming to isolate complexes with a unique Ca─Ca bond, we serendipitously found N2 activation by low-valent CaI radicals (Scheme 1c, I).[11] This was followed by several examples of Mg/K and Ca/K-mediated N2 fixation by Jones and coworkers (Scheme 1d, II-III).[12, 13] Calcium complex I should be regarded to consist of N22− ions that bridge two Ca2+ centers in a side-on (μ-η2,η2)-fashion. Although we never achieved the isolation of a “true” CaI complex, I reacts as a highly reducing CaI synthon by releasing N2 and two electrons. In this function it is able to convert highly stable aromatic arenes like benzene into 8π-electron, anti-aromatic C6H62ˉ (Scheme 1e) which in turn functions as a CaI synthon by release of the arene and two electrons.[14] In addition, dehydrogenative benzene-to-benzene coupling was shown to give biphenyl complexes.[15] These latter investigations showed that the Sr complexes reacted much faster and more selective than the corresponding Ca complexes. Since it is well known that group 2 metal reactivity increases steadily going down the group (Be < Mg < Ca < Sr < Ba),[16] we targeted Sr-mediated N2 activation and the challenging isolation of labile, highly air-sensitive SrI synthons with strongly reducing N22− ions. Herein, we describe our combined computational and experimental studies.

Results and Discussion

Computational Studies on the Ae─Ae Bond and N2 Activation

Computational studies on the Ae─Ae bond strength in CpAeAeCp model systems have been reported for the full series of alkaline-earth (Ae) metals.[17, 18] Except for the most stable complex in this series, CpBeBeCp,[19] these are fictitious species. Given that the β-diketiminate (BDI) ligands play a prominent role for stabilization of Ae metals in low oxidation states,[20-22] it is surprising that theoretical work on (BDI)AeAe(BDI) complexes is limited only to Mg and Ca.[23, 24] In order to gain insight on the general stability of (BDI)AeAe(BDI) complexes and the thermodynamics of their reactivities with N2, we started this project with DFT calculations on the full series (Ae = Be, Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba).

Using the standard BDI ligand with DIPP-substituents (BDI = HC[(Me)C = N-DIPP]2, DIPP = 2,6-Me2CH-phenyl), we modelled the complete series of (BDI)AeAe(BDI) complexes (Figure 1); details can be found in the Supporting Information. The validity of our method was confirmed by the fact that the calculated Mg─Mg bond of 2.883 Å fits the experimental value of 2.8457(8) Å quite well and NPA charges on Mg (+0.98) are in line with Mg+I.

The Ae─Ae bond for the heavier metals (Ca, Sr, Ba) become rather long and the heaviest complexes in the series (Sr and Ba) show Ae-arene interactions (Figures 1 and S75). This asymmetry results in partial transfer of electron density from the ring-stabilized Ae metal to the Ae nucleus without this stabilizing interaction. The NPA charges on the metals in (BDI)BaBa(BDI) are now +1.26 (ring-stabilized) and + 0.69 (3-coordinate Ba). This asymmetry is only found for the heavier complexes and only when dispersion is included. Optimization of (BDI)BaBa(BDI) without dispersion correction resulted in a symmetric dimer with 3-coordinate Ba metals and a NPA charge of +0.94 on each Ba nucleus (Figure S76). However, the unrealistically long Ba-Ba distance of 4.75 Å and a negative free energy for homolytic cleavage (ΔG = −1.8 kcal mol−1) indicate instability.

The BDI ligand is clearly too bulky for Be and an extremely long Be-Be distance of 2.624 Å in (BDI)BeBe(BDI) is calculated. For comparison, the experimentally determined Be-Be distance in CpBeBeCp is only 2.055(2) Å.[19]

All (BDI)AeAe(BDI) complexes are thermodynamically stable toward disproportionation into (BDI)2Ae and atomic Ae0 but this stability rapidly decreases down the group. However, if one considers the metal atomization enthalpies (kcal mol−1: Be 77.7, Mg 35.5, Ca 42.6, Sr 39.3, Ba 43.1), none of the complexes are stable. Disproportionation to (BDI)2Ae and metallic (Ae0)n is in all cases exothermic. Their existence can only be rationalized with high kinetic barriers for disproportionation.

In agreement with experiment,[25] Atoms-In-Molecules (AIM) analysis (Figure S84) shows a Non-Nuclear-Attractor (NNA) with a basin of 0.80e at the Mg-Mg axis. All other (BDI)AeAe(BDI) complexes do not have NNA's on the Ae-Ae axis but show weak Ae─Ae bond paths with low values for the electron density ρ(r) and Laplacian ∇2ρ(r) in the bond-critical-points (bcp’s). These values steadily decrease from Be to Ba. However, optimization of the structures without considering dispersion results in even longer Ae-Ae distances and in this case also NNA's are observed for the Ca─Ca (basin: 0.33e) and Sr─Sr (basin: 0.35e) bonds (Figures S85–S86).

Homolytic Ae─Ae bond cleavage is slightly endergonic with bond energies rapidly decreasing down the group. Only for (BDI)BeBe(BDI) an exergonic cleavage is found. This is related to steric stress between the two oversized BDI ligands. Due to the rather low bond energies for the heavier Ae─Ae (Ca, Sr, Ba) bonds, it is plausible that these species are in equilibrium with highly reactive (BDI)Ae● radicals dominating their reactivities.

Steric stress in (BDI)BeBe(BDI) is also released by reaction with N2 which is highly exergonic, especially for end-on N2 bridging in which case BDI···BDI repulsion is reduced even further. For all other metals, side-on N2 coordination is preferred. In the range of (BDI)AeAe(BDI) complexes, the Mg complex is the only complex for which N2 fixation is endergonic. In this light, the recently observed N2 activation with a low-valent Mg complex is remarkable (III).[12] Since for the Mg-N2 complex III the triplet state was calculated to be 13.9 kcal mol−1 more stable than the singlet state, far-fetching conclusions from this preliminary computational study can only be drawn after full evaluation of the alternative triplet states. As we reported earlier for Ca-N2 complex I,[11] the activation of N2 likely proceeds through reactive (BDI)Ae● radicals.

The calculations in Figure 1 suggest that hypothetical (BDI)SrSr(BDI) is only weakly bound and unstable. In contrast, the corresponding Sr-N2 complex is nearly as stable as the Ca-N2 complex I and was target of further experimental investigations.

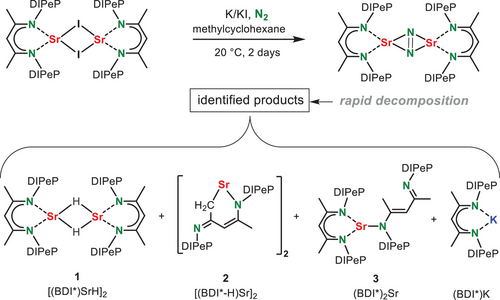

Experimental Studies on N2 Activation with SrI

The successful verification of N2 activation with an in situ formed low-valent β-diketiminate Ca complex (Scheme 1c) was enabled by introduction of a super bulky ligand with DIPeP-substituents at N: HC[(Me)C = N-DIPeP]2, DIPeP = 2,6-Et2CH-phenyl. This ligand, abbreviated herein as BDI*, is not only very bulky[26] but its flexible alkyl arms enable dissolution of the highly reducing products in inert alkane solvents.[11] Aromatic solvents would be immediately reduced to 8π-electron, anti-aromatic dianionic rings. (cf. Scheme 1e). Using the BDI* ligand, N2 activation studies with in situ generated low-valent SrI can be performed in alkane solvents.

The room temperature reduction of [(BDI*)SrI]2 with K/KI[27] under an N2 atmosphere in methylcyclohexane (Scheme 2) led to various products that can be conveniently assigned by their typical 1H NMR signals for the backbone methine group in the BDI* ligand (Figure S51). Thus, we were able to identify the products [(BDI*)SrH]2 (1), [(BDI*-H)Sr]2 (2) and (BDI*)2Sr (3) as well as overreduction to (BDI*)K. This was confirmed by addition of THF and crystallization of the THF adducts of 2·(THF)2 and 3·(THF)2 which were identified in the product mixture by X-ray diffraction (Figures S52 and S54). Compounds 1 and 2 are proposed to be formed by reductive cleavage of the C─H bond of the backbone Me group. Formation of 3 may be explained by disproportionation of (BDI*)SrSr(BDI*) as described in Figure 1. Although a solid-state mechanochemical reduction of [(BDI*)SrI]2 with K/KI using the ball-mill gave a different product distribution (Figure S53), we have not been able to identify or isolate the expected (BDI*)Sr(μ-N2)Sr(BDI*) product. This stands in strong contrast with the successful isolation of the corresponding Ca complex I.[11] Failure to isolate the target Sr complex is most likely due to its longer, more ionic, and weaker bonds which result in a much higher reactivity and lower stability.

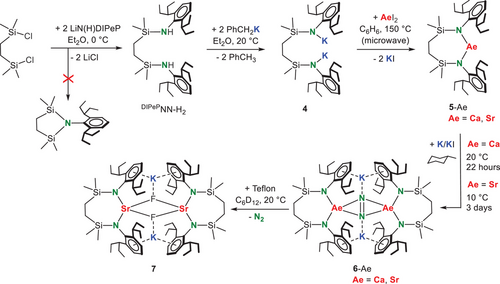

Heterobimetallic N2 Activation

To increase complex stability, we chose to follow a heterobimetallic approach. This concept, which is directly related to Mulvey's inverse crown ether chemistry,[28] takes advantage of stabilizing anions in a crown of metal cations and was recently successfully used to stabilize N22− (cf. II-III)[12, 13] or the SiH62ˉ anion.[29] The essential building blocks for this chemistry are a chelating bis-amide ligand, an Ae2+ cation and an alkali metal cation.[12, 13] [29-33] Most recently, bis-amide complexes of the heaviest Ae metals Sr and Ba have been reported.[32, 34] However, these compounds were found to be notoriously insoluble in non-donor solvents. Modifying a ligand synthesis of Hill and coworkers,[30] we developed a considerably more soluble and bulkier bis-amide ligand system based on the DIPeP-substituent (DIPePNN, Scheme 3). The preligand (DIPePNN-H2) was obtained in quantitative yield by reaction of (DIPeP)N(H)Li with a chlorosilane bridge in Et2O at 0 °C (crystal structure: Figure S68). Solvent choice and temperature control are essential to avoid cyclic side-products. For comparison, reaction of this bridge with the less bulky (DIPP)N(H)Li led to considerable quantities of a cyclic side-product,[30] showing that the use of very bulky substituents is also advantageous in ligand preparation.

Deprotonation of DIPePNN-H2 with benzylpotassium gave (DIPePNN)K2 (4) (crystal structure of its THF adduct: Figure S69). Using salt-metathesis, 4 could be converted to the heavier Ae metal complexes 5-Ae (Ae = Ca, Sr). As we aim for donor-free products this conversion was performed in benzene. Due to the bulk of the ligand this was a challenging reaction. However, using harsh microwave conditions the complexes could be obtained in >80% isolated yields.

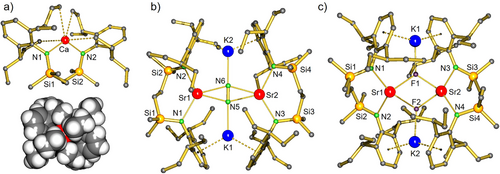

The crystal structure of 5-Ca (Figure 2a) shows a monomeric complex with approximate, non-crystallographic, C2-symmetry. Product 5-Ca is an odd example of a complex with a bent two-coordinate metal center. With a N-Ca-N angle of 119.86(4)°, a large part of the Ca coordination sphere remains “naked”. The bulky DIPePNN-ligand restricts dimerization and instead provides only weak secondary Ca···CH3CH2 interactions (Ca···C: 3.090(2)-3.134(2) Å). Donor-free 5-Sr could not be crystallized but the C2-symmetric complex 5-Sr·(THF)2 is monomeric with a four-coordinate Sr atom that shows Sr─N and Sr─O bonds of 2.466(2) Å and 2.591(2) Å, respectively (Figure S70).

Reduction of the donor-free monomeric bis-amide complexes 5-Ae with K/KI[27] in methylcyclohexane gave the corresponding N2 complexes 6-Ae. Reductions with KC8 or K0 gave the same products but were less selective. The conversion of 5-Ca with K/KI was clean and the raw product is essentially pure. After crystallization 6-Ca was isolated in the form of orange crystals in 83% yield. Isolation of the analogue6-Sr required temperature lowering to 10 °C. Temperatures below 10 °C gave very slow conversion, higher temperatures led to product decomposition. Despite temperature control, the formation of 6-Sr was only circa 75% selective and the product could be crystallized in a low yield of 9%. This much lower yield is not only due to instability but also to its very high solubility in alkanes.

Although 6-Ca and 6-Sr crystallize in different space groups, their structures are very similar (Figures 2b and S72–S73). The crystal structure of 6-Ca is highly symmetric (space group Fddd, D2 symmetry) with three perpendicular crystallographic C2 axes through the center of the aggregate. Complex 6-Sr shows no crystallographic symmetry but is close to being D2 symmetric. The Ae2+ and K+ cations and embedded N22− anion are coplanar, showing side-on Ae-N2-Ae and end-on K-N2-K bridging.

Table 1 summarizes some of the most important bond distances and angles for 6-Ae in comparison to other known Ae-N2 complexes. The Ca-N2 distances in 6-Ca are nearly 0.1 Å longer than those in II. For that, the K-N2 distances in 6-Ca are nearly 0.1 Å shorter than those in II. Although the ionic radius of Sr2+ (1.18 Å, 6-coordinate) is 0.18 Å larger than that of Ca2+ (1.00 Å, 6-coordinate),[35] the Sr-N2 bonds in 6-Sr are only 0.12 Å longer than the Ca─N2 bonds in 6-Ca. This indicates a very tight Sr-N2 interaction which results in longer K─N2 bonds in 6-Sr. The N-N distances vary from 1.230(9)-1.265(3) Å which is the typical range for N = N bonding in N22−; for comparison the triple bond in N2 has a length of 1.098 Å. The small variation in N = N bond lengths and partially large standard deviation as well as different coordination geometries do not allow for clear-cut conclusions on the degree of bond activation. Measurement of the Raman frequencies is probably a more accurate method to evaluate N2 activation. Unfortunately, complexes 6-Ae are both sensitive to laser light and decompose upon radiation (Figures S41 and S49). Although this is especially the case for 6-Sr, a weak N = N stretching band could be observed at 1428 cmˉ1 (6-Ca: 1440 cmˉ1). The efficiency of N2 activation increases along the row: III < 6-Ca < 6-Sr < II < I. In general, N2 activation increases with metal size Mg < Ca < Sr. Activation is also considerably stronger in the homometallic Ca complex I when compared to heterobimetallic Ca/K complexes (6-Ca or III).

| Complex | 6-Ca | 6-Sr | I·(THF)2 | II | III |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ae-NLa) | 2.373(3) |

2.522(3)-2.533(3) [2.526] |

2.393(2), 2.396(2) [2.395] |

2.342(3)-2.354(2) [2.346] |

2.047(3)-2.069(2) [2.056] |

| Ae-N2 | 2.4324(17) |

2.527(2)- 2.565(3) [2.552] |

2.301(2), 2.303(2) [2.302] |

2.348(2)-2.357(2) [2.351] |

1.987(2)-1.993(2) [1.990] |

| K-N2 | 2.608(5) |

2.668(3), 2.707(3) [2.688] |

− |

2.688(3), 2.692(3) [2.690] |

2.762(3)-2.819(3) [2.793] |

| N-N | 1.230(9) | 1.251(4) | 1.258(3) | 1.265(3) | 1.255(2) |

| NL-Ae-NL | 112.5(2) |

123.2(1), 122.4(1) [122.8] |

83.9(1) |

130.2(1), 130.2(1) [130.2] |

140.2(1), 140.7(1) [140.5] |

| N-N (Raman) | 1440 | 1428 | 1375 | 1419 | 1530 |

- a) NL is the N of the DIPePNN-ligand.

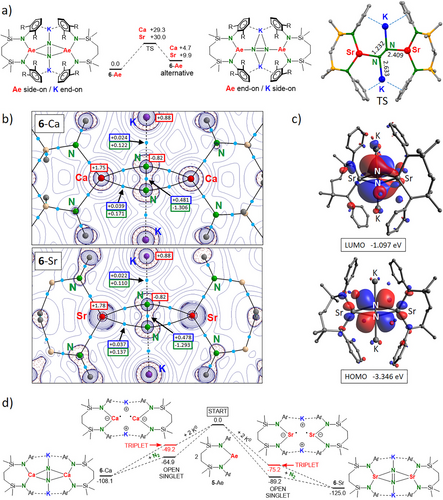

The computed structures of 6-Ae compare well to the crystal structures (Figure S90). We also located energy minima for alternative structures in which the coordination mode for N22− switched to end-on Ae-N2-Ae and side-on K-N2-K bridging (Figure 3a). For 6-Sr this alternative structure is high in energy (ΔH = +9.9 kcal molˉ1) but for 6-Ca it is more stable (ΔH = +4.7 kcal molˉ1). The heterobimetallic Mg/K-N2 complex III favors end-on Ae-N2-Ae bonding.[12] Therefore, the tendency to form end-on complexes decreases from Mg > Ca > Sr. This may be explained by the higher electronegativity of Mg which favors more covalent σ-bonding. It could also be rationalized by the Hard-Soft-Acid-Base theory in which the smaller Mg2+ prefers bonding with the more compact end-on sp-hybrid orbitals whereas larger metal cations like Ca2+ and Sr2+ favor interaction with the more diffuse p-orbitals.

In the transition state for N2 rotation, the N22− dianion has been rotated within the Ae(N2)Ae plane by circa 45° and is now end-on bridging the Ae2+ and K+ cations in μ4-fashion (Figure 3a). For both, Ca and Sr, the energy barriers are relatively high (ΔH = +29.3 and +30.0 kcal molˉ1, respectively). Therefore, such rotational processes are unlikely at room temperature.

Atoms-In-Molecules (AIM) shows bond paths between the N2 nuclei and the Ae metals (Figure 3b). Small values for the electron density ρ(r) and Laplacian ∇2ρ(r) in the bcp’s indicate ionic Ae─N2 bonding. This is confirmed by the calculated NPA charges in 6-Ca (Ca: +1.75, N2: −1.64) and 6-Sr (Sr: +1.78, N2: −1.66). Both complexes have similar HOMO's and LUMO's. The HOMO for 6-Sr clearly shows d-orbital contribution of Sr (5.4% for each Sr atom) overlapping with the in-plane N2 π*-orbital (Figure 2c). The d-orbital contribution for Ca in 6-Ca is somewhat smaller (4.0% for each Ca atom). The LUMO's are located on N2 and consist mainly of the N2 π*-orbital perpendicular on the Ae(N2)Ae plane.

The energy profile for N2 activation shows that this is a highly exothermic process. Formation of 6-Sr from 5-Sr and K0 (ΔH = −125.0 kcal molˉ1) is considerably more exothermic than the formation of 6-Ca (ΔH = −108.1 kcal molˉ1); Figure 3d. Although there are many possible pathways for product formation, we propose the following Ae intermediates: {[(DIPePNN)AeI]ˉK+}2. Formation of these intermediates is also quite exothermic. The large energy differences of circa 15 kcal molˉ1 between the triplet and unrestricted open singlet state indicates that, despite large Ae···Ae distances, these proposed intermediates have little diradicaloid character.[36]

Both, 6-Ca and 6-Sr, are reasonably well soluble in alkanes. 1H NMR spectra of a cyclohexane-d12 solution of 6-Ca show over a large temperature range (−40 °C to + 80 °C) broad resonances (Figure S39). In contrast, the 1H NMR spectrum of 6-Sr in cyclohexane-d12 shows at 25 °C mainly sharp well-resolved resonances corresponding to the high symmetry in the crystal structure (Figure S42). Line-broadening of the C(H)Et2 signals may be attributed to dynamic anagostic C(H)Et2···Sr interactions. The broad 1H NMR signals for 6-Ca compared to sharp resonances for 6-Sr may be explained by different singlet-triplet gaps. Although for both compounds the singlet state is most stable, both show very small singlet–triplet gaps (ΔH for Ca: 2.1 kcal mol−1, Sr 0.3 kcal mol−1). The differences in signal broadening are therefore likely related to differences in metal sizes and complex dynamics like the ring puckering of the seven-membered silazane ring.

In form of pure compounds 6-Ca and 6-Sr are fully stable in benzene, even at reflux temperature. This stands in strong contrast with complex II which instantly decomposed when dissolved in benzene.[13] Even the Mg-N2 complex III is able to reduce benzene.[37] As the N22− anions in 6-Ca and II or III are in all cases highly protected by super bulky ligands, this difference in stability is unclear.

In strong contrast, methylcyclohexane-d14 solutions of 6-Ca and 6-Sr both reacted already at −75 °C with H2. However, despite these controlled conditions, these reactions were unselective and well-defined products could not be isolated. Also, reactions with I2 led to the formation of several products that could not be identified. During our investigations on the synthesis of 6-Sr, a small batch of yellow crystals was isolated. X-ray diffraction showed a dimeric complex of composition [(DIPePNN)SrKF]2 (7, Figure 1d). The presence of fluoride was confirmed by a 19F NMR resonance at –68.1 ppm (298 K, C6D12). The compound, which has a similar build up as a previously reported heterobimetallic Ca/K fluoride complex,[31] could be considered a soluble form of K+Fˉ stabilized between two neutral (DIPePNN)Sr fragments. However, as the 19F NMR signal of complex 7 slowly disappeared over time, the complex was found to be quite unstable in solution. From the appearance of 1H NMR signals for (DIPePNN)Sr (5-Sr), we assume that precipitation of KF salt is the driving force for this decomposition.

The origin of the fluoride anions in 7 is undoubtedly the Teflon-coated stirring bars used in the synthesis of 6-Sr. Indeed, the Teflon-coated stirring bars generally turned black during these experiments. For this reason, it is advisable to use glass-coated stirring bars for this chemistry.

Additional proof for this reactivity was found in the very fast reaction of 6-Sr with Teflon powder. The addition of commercially available Teflon powder to a cyclohexane solution of 6-Sr led to immediate gas evolution and a colour change from white to black, a reaction that was complete within minutes. In addition to 19F NMR resonances of Teflon decomposition products, we observed a strong resonance at –68.4 ppm which is indicative for 7 (Figure S59). However, due to the poor stability of this complex we have not been able to isolate larger quantities. Similar observations were made for the reactivity of 6-Ca with Teflon powder. The fast reaction of Teflon with 6-Ca and 6-Sr, which are CaI and SrI synthons, contrasts with the much lower reactivity of a MgI complex which needs activation by dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) and long reaction times to reach full conversion at room temperature.[38]

Conclusion

According to DFT calculations, (BDI)SrSr(BDI) is thermodynamically not stable toward SrII/(Sr0)n disproportionation. As the Sr─Sr bond energy is smaller than 20 kcal molˉ1, also homolytic cleavage is facile. However, similar as found for the analogue Ca compounds, N2 activation to give a stable (BDI)Sr(μ-N2)Sr(BDI) complex with a side-on bridging N22− dianion should be feasible. However, while (BDI*)Ca(μ-N2)Ca(BDI*) stabilized by super bulky BDI* ligands have been synthesized, all attempts to prepare the comparable Sr complex failed and only decomposition products could be isolated. This instability is likely the result of the higher ionicity of Sr compounds and the much larger size of Sr2+ (1.18 Å) compared to Ca2+ (1.00 Å). Both make the target Sr complex much more reactive than (BDI*)Ca(μ-N2)Ca(BDI*).

The first example of N2 fixation with a Sr complex could be realized using a heterobimetallic approach. In complex 6-Sr the N22− anion is embedded in a metal crown consisting of two Sr2+ and two K+ cations. While the Sr2+ cations bind the N22− anion in a side-on fashion, the K+ cations are coordinated end-on. Calculations show that a structure with side-on Sr─N2 bonding is 9.9 kcal molˉ1 more stable than alternative end-on Sr─N2 bonding. The transition state between these two conformations is high (ΔH = 30.0 kcal molˉ1), indicating that at room temperature there is no free N2 rotation. The HOMO of 6-Sr mainly consists of a N2 π* orbital but also has considerable contributions of both Sr d-orbitals. With NPA charges of + 1.78 on Sr and −1.66 on N2 bonding in 6-Sr is mainly of ionic nature. A similar synthetic approach led to isolation of the analogue Ca complex 6-Ca.

Preliminary reactivity studies show that both, 6-Ca and even 6-Sr, are stable in benzene under reflux conditions. Considering the facile reduction of benzene with known bulky Ae-N2 complexes, it is unclear why 6-Ae would not react with benzene. However, both 6-Ae complexes react under release of N2 smoothly with H2 or I2 but the products of these reactions could not be isolated. The very high reactivity of 6-Sr as a synthon for low-valent SrI was demonstrated by the reduction of Teflon (used as stirring bar coating) which is generally highly inert. This gave a small quantity of crystalline [(DIPePNN)SrKF]2 (7) which could be seen as a molecular KF embedded between two (DIPePNN)Sr compounds. Unfortunately, this complex is very labile and easily loses KF. The stirring bar as source of fluoride was confirmed by the vigorous N2 release when 6-Ae complexes are brought in contact with Teflon powder. This reactivity underscores potential use of 6-Ae complexes as very strong reducing agents which are hydrocarbon-soluble and can be dosed in exact stoichiometry. We are currently targeting the most challenging isolation of even more reactive Ba-N2 complexes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank A. Roth for CHN analyses, Dr. C. Färber and J. Schmidt for assistance with NMR analyses, K. Gerein for the Raman measurements of 6-Ca and 6-Sr and D. Pusztai for assistance with reactivity studies. The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft is acknowledged for funding (HA 3218/12–1). Dr. N. Patel is grateful for funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme as a Marie Skłodowska-Curie post-doctoral fellow on the NITRO-EARTH project (101064276).

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Electronic Supporting Information available

Experimental details, NMR spectra, crystallographic details including ORTEP, details for DFT calculations.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.