Bis(N-Heterocyclic Carbene) Manganese(I) Complexes: Efficient and Simple Hydrogenation Catalysts

Abstract

The use of bis(NHC) manganese(I) complexes 3 as catalysts for the hydrogenation of esters was investigated. For that purpose, a series of complexes has been synthesized via an improved two step procedure utilizing bis(NHC)-BEt3 adducts. By applying complexes 3 with KHBEt3 as additive, various aromatic and aliphatic esters were hydrogenated successfully at mild temperatures and low catalyst loadings, highlighting the efficiency of the novel catalytic system. The versatility of the developed catalytic system was further demonstrated by the hydrogenation of other substrate classes like ketones, nitriles, N-heteroarenes and alkenes. Mechanistic experiments and DFT calculations indicate an inner sphere mechanism with the loss of one CO ligand and reveal the role of BEt3 as cocatalyst.

Introduction

The reduction of esters to alcohols is an important reaction in academic and industrial chemistry. Traditionally, this transformation has been performed in the presence of stochiometric amounts of metal-hydrides (e.g. LiAlH4, DIBAL-H, NaBH4), which obviously comes along with the formation of stochiometric amounts of waste, often tedious workup procedures and limited functional group tolerance. In this regard, the catalytic hydrogenation using H2 gas represents an environmentally and economically more attractive approach. Indeed, fatty acid esters are hydrogenated since many decades to the corresponding fatty alcohols using heterogeneous copper chromite catalysts;1 however, harsh reaction conditions (>200 °C, 40–300 bar) are necessary, which omit the use of more sensitive substrates.2 Therefore, the development of alternative systems working under milder conditions has attracted much attention over the last two decades and several active homogeneous catalysts working at lower temperature and/or pressure mainly based on Ru3 but also on Os3d and Ir4 have been reported.

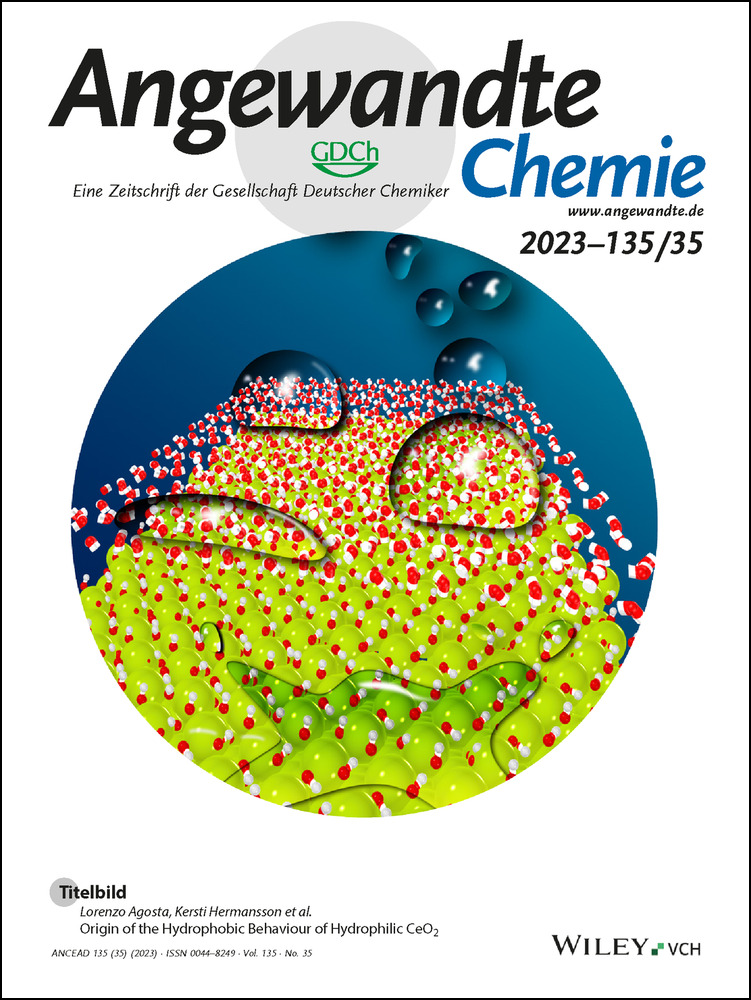

More recently, many efforts focused on the replacement of noble-metals in such molecularly-defined catalysts by more abundant and cheaper 3d metals such as Mn,5 Fe,6 Co,7 and Cu.8 Especially Mn9 attracted much scientific attention due to the limited knowledge of such complexes as hydrogenation catalysts. As shown in Figure 1, most of the reported systems rely on phosphine-based pincer ligands and include N−H or C−H acidic sites in the ligand-backbone according to the concept of bifunctional metal-ligand cooperativity.10 From this low structural diversity, one might get the impression that a bifunctional ligand is essential for an efficient Mn-based hydrogenation catalyst. Yet, there are scarce examples of Mn complexes bearing non-bifunctional, bidentate phosphine ligands for catalytic hydrogenation reactions.11

Selected examples of Mn-based catalysts for the hydrogenation of carboxylic acid esters.

However, phosphine-based ligands come along with certain disadvantages, e.g. the sensitivity towards oxygen and their often tedious preparation procedures. In this regard, N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) offer a promising alternative to phosphine ligands and several efforts were made very recently, to replace phosphines in the classical PNP and NNP ligands by NHCs (e.g. Figure1, Pidko and Filonenko 2022, Liu 2023).5f, 5h, 12 Notably, due to their strong σ-donor and relatively weak π-acceptor properties, these carbene-based ligands allow for the formation of stable Mn complexes13 and the strong electron donation paired with less steric demand at the active coordination sites compared to phosphines often leads to an enhanced reactivity of the corresponding Mn hydrido complexes.5h Hence, bidentate bis(NHC) ligands represent an attractive ligand class for hydrogenation catalysts due to their strong electron-donating properties as well as their easy and modular synthesis allowing for the convenient finetuning of electronic and steric properties of the corresponding Mn complexes. In 2018, Mn complexes bearing these bidentate bis(NHC) ligands were described for the electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO14 and, recently, their application has been extended to hydrosilylation,15 dehydrogenative coupling16 and transfer hydrogenation17 reactions. However, so far these systems have not been explored as catalysts for direct hydrogenation reactions. Some time ago, our group reported a Ru-based catalyst for the hydrogenation of esters containing the same bis(NHC) ligand motif,18 therefore, we were curious about the performance and the potential advantages of bis(NHC) Mn complexes in catalytic hydrogenation reactions. Here, we report the synthesis of a series of Mn complexes bearing bidentate bis(NHC) ligands and their successful use as efficient catalysts for the hydrogenation of carboxylic acid esters. This work represents scarce examples of Mn-based hydrogenation catalysts with non-bifunctional ligands. During the preparation of this manuscript a related catalytic system has been reported by the groups of Bastin and Sortais.19

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Characterisation of bis(NHC)-BEt3 Adducts 2 ⋅ 2 BEt3 and bis(NHC) Mn Complexes 3

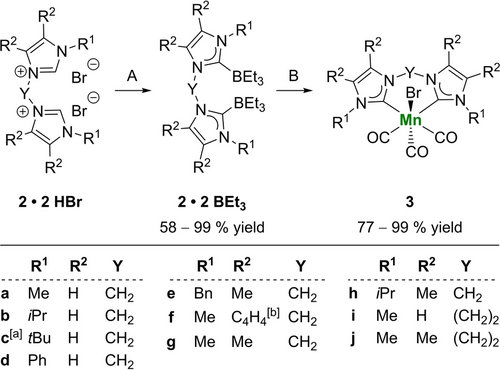

Initially, we prepared bis(imidazolium) salts 2 ⋅ 2 HBr from the corresponding alkyl dibromides and imidazoles 1 at 130 °C in almost quantitative yields.15b, 20 Notably, in the preparation of the ethylene-bridged bis(imidazolium) salt 2 j ⋅ 2 HBr with highly basic 1,4,5-trimethylimidazoles partial elimination occurred even at lower temperature (70 °C) (see SI, section 4). However, the resulting monoionic side products could be easily removed by washing with DCM due to their better solubility in that solvent. The direct preparation of bis(NHC) manganese complexes 3 from bis(imidazolium) salts, KOtBu and MnBr(CO)5 required more tedious aqueous workup/purification procedures leading to the corresponding complexes in moderate yields.14 Therefore, an improved protocol for their synthesis via NHC-BEt3 adducts as intermediates was developed. Using LiHBEt3 for deprotonation and as BEt3 source,21 we observed a nucleophilic attack at the bridging, electrophilic carbon atom leading selectively to a mono(NHC)-BEt3 adduct and 3-(triethylborane)-1-methylimidazole (see SI, section 5). Fortunately, the use of the less nucleophilic, sterically demanding base NaHMDS and the separate addition of BEt3 resulted in the clean formation of desired 2 ⋅ 2 BEt3. A small number of BEt3-adducts 2 ⋅ 2 BEt3 was obtained as white to yellow solids in most cases in very good to quantitative yields and all compounds have been analyzed by 1H, 13C and 11B NMR spectroscopy as well as elemental analysis (Scheme 1).

Synthesis of bis(NHC) MnI complexes 3 from bis(imidazolium) bromides 2 ⋅ 2 HBr via bis(NHC)-BEt3 adducts 2 ⋅ 2 BEt3. Conditions A: 1) NaHMDS (2.1 eq.), 2) BEt3 (2.1 eq.), THF, −78 °C to rt, 16 h. Conditions B: Mn(CO)5Br (1.0 eq.), THF, reflux, 16 h. [a] 2 c ⋅ 2 BEt3 and 3 c were not synthesized. [b] Benzimidazol/benzimidazolilydene.

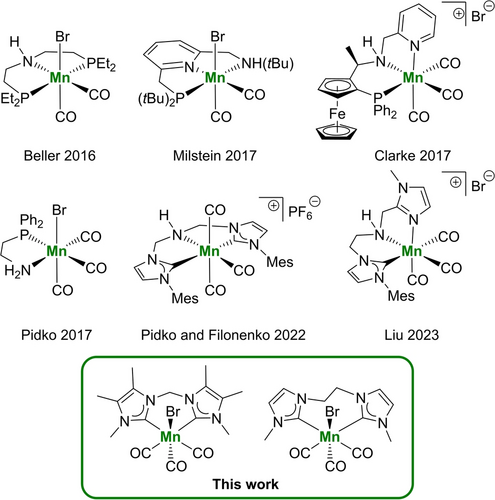

By refluxing bis(NHC)-BEt3 adducts 2 ⋅ 2 BEt3 with Mn(CO)5Br in THF complexation of the bis(NHC) ligands under loss of two CO ligands occurred (Scheme 1). After washing with Et2O and n-pentane, complexes 3 were obtained as yellow to orange powders in good to very good yields (>80 %). Further purification could be achieved by recrystallisation of these powders from DCM/n-pentane mixtures to remove bis(imidazolium) salt impurities. In general, complexes 3 were characterized by NMR and IR spectroscopy, HR-MS, elemental analysis and in some cases single crystal X-ray diffraction (Figure 2). The obtained data is consistent with related manganese complexes.14, 16b

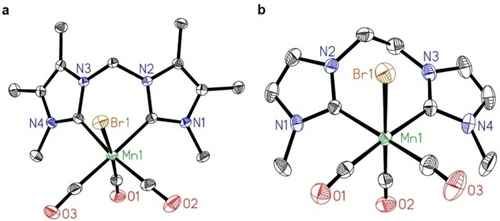

Molecular structures of a) complex 3 g and b) complex 3 i in the solid state. Displacement ellipsoids set at 50 % probability level. Hydrogen atoms and solvent molecules omitted for clarity. For the structure of 3 i only one of the two molecules of the asymmetric unit is shown.22

In most cases, 1H NMR spectra of complexes 3 show broad signals at room temperature, which can be assigned to a fluxional behavior of the ligand conformation in solution. From the obtained molecular structure of complex 3 g (Figure 2a) as well as the literature-known structure of 3 a,14 it is well visible that for methylene-bridged complexes (Y=CH2) the ligand backbone is bent, adopting a boat-shape conformation similar to complexes of other transition metals, e.g. Pd,23 Rh,24 Ir,25 Cr,26 Mo26 or W26. The methylene-bridge between the NHC units either points towards (syn) or away (anti) from the bromido ligand, allowing for two possible diastereomer conformers both with Cs-symmetry (SI section 9, Figure S18) For structure 3 a, the syn-conformer is computed to be more stable than the anti-conformer by 1.69 kcal/mol, and the ring inversion barrier is 13.52 and 11.83 kcal/mol for the forward and backward inversion, respectively, indicating an equilibrium of the two conformers and the reversibility of the ring inversion at room temperature.

For ethylene-bridged complexes (Y=(CH2)2), there are also such syn- and anti-conformations regarding the position of the ethylene-bridge and the bromido ligand. Additionally, the ethylene-bridge can adopt either an eclipsed or staggered conformation, giving four conformers in total (SI section 9, Figure S19). DFT calculations show that the different conformers are close in energy, therefore we assume that interconversion leads to broad signals in the NMR spectra at room temperature. At elevated temperatures (373 K) sharper peaks are observed; however, a clear assignment of resonances was not possible in most cases. As an exception, complexes 3 a and 3 g with methyl substituents at the wing tips (R1=Me) show sharp NMR resonances at room temperature. We assume that for these substituents interconversion between the conformers is fast due to less steric repulsion between R1 and the CO ligands. The IR spectra of complexes 3 feature strong absorption bands of the CO ligands. According to their Cs symmetry, methylene-bridged complexes show three CO absorptions, typically between 2000 and 1860 cm−1. For complex 3 i four absorption maxima are observed, likely due to the presence of different conformers as discussed above (compare Supporting Information section 9, Figure S19). In contrast, complex 3 j, for which only the staggered syn- and anti-conformer in close energy (0.09 kcal/mol) were computed to be stable, only exhibits three CO bands. Ionization of complexes 3 by ESI took place under cleavage of the bromido ligand and the resulting positive fragment was detected by HRMS.

Catalytic Hydrogenation of Esters

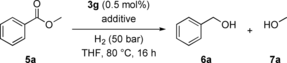

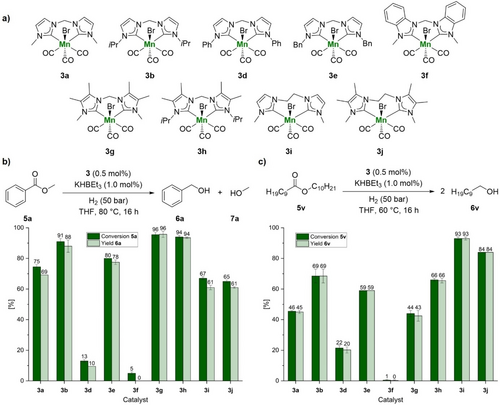

Having a small library of synthesized bis(NHC) MnI complexes 3 in hand, we tested them for ester hydrogenation using methyl benzoate 5 a and decyl decanoate 5 v as model substrates for aromatic and aliphatic esters, respectively (Scheme 2). In these experiments, 1 mol% of KHBEt3 was added to activate the precatalysts. To differentiate the performance from most previously known manganese-based hydrogenation catalysts, we applied low metal loading (0.5 mol%) at comparably low temperatures of 60–80 °C for both benchmark reactions.

Catalytic performance of bis(NHC) MnI complexes 3 for the hydrogenation of esters. a) Lewis structures of bis(NHC) MnI complexes 3. Catalyst comparison for the hydrogenation of b) methyl benzoate 5 a and c) decyl decanoate 5 v. Values represent the average of two experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviation. Reaction conditions: 1 mmol methyl benzoate 5 a or decyl decanoate 5 v, 5 μmol 3 (0.5 mol%), 10 μmol KHBEt3 (1.0 mol%), 4.0 ml THF, 50 bar H2, 80 °C (methyl benzoate 5 a) or 60 °C (decyl decanoate 5 v), 16 h. Conversion of methyl benzoate 5 a or decyl decanoate 5 v and yield of benzyl 6 a alcohol or 1-decanol 6 v were determined by GC using hexadecane as internal standard. The differences of conversion and yield in the case of methyl benzoate 5 a are mainly due to the formation of benzyl benzoate via transesterification.

For the hydrogenation of methyl benzoate 5 a, complexes 3 g and 3 h with a 4,5-dimethyl-imidazol backbone (R2=Me) showed the best activity with almost full conversion and yield. In comparison to 3 g, the activity decreased for complex 3 a with a less electron-donating imidazole backbone (R2=H) and almost no conversion was observed for complex 3 f with the benzimidazole backbone. For the wing tip substituent R1, also increasing catalytic activity with increasing electron-donation of the substituent in the order of Ph<Me<Bn<iPr (3 d≪3 a<3 e<3 b) is observed. Ethylene-bridged complexes 3 i and 3 j showed worse catalytic activity than their methylene bridged congeners 3 a and 3 g, which we assign to changes in the complex geometry rather than the electronic properties of the present bis(NHC) ligands.

In contrast, the hydrogenation of decyl decanoate 5 v using ethylene-bridged complexes 3 i and 3 j proceeded better than with methylene-bridged analogues leading to high conversions and yields of the desired product. Regarding wing tip substituent R1, the same trend as for methyl benzoate has been observed and catalytic activity enhanced with increasing electron donation of the substituent (3 d<3 a<3 e<3 b). Dimethylation of the ligand backbone had almost no effect on the catalytic performance leading to similar results for complexes 3 a and 3 g as well as 3 b and 3 h, respectively. In case of complex 3 f bearing a benzimidazole backbone, no hydrogenation was observed. Overall, the best results were obtained with complex 3 g for the hydrogenation of methyl benzoate 5 a and with complex 3 i for the hydrogenation of decyl decanoate 5 v.

Generally, the catalytic activity of complexes 3 correlates with the electron donator strength of the corresponding bis(NHC) ligand, which interestingly is in agreement with observations using palladium complexes.27

In general, molecularly defined ester hydrogenation catalysts require the addition of significant amounts of strong basic reagents, e.g. 2–75 mol% of KOtBu.5 Hence, the influence of the used additive and additive loading was explored in more detail. Also, other crucial parameters such as reaction temperature, catalyst loading, and hydrogen pressure were investigated, too (Table 1). While applying only 1 mol% of KHBEt3 as additive led to almost full conversion of 5 a and high yield of 6 a (entry 1), KOtBu, KHMDS and KH at the same additive loading showed significantly lower conversions and yields (entries 2, 4 and 5). At an increased additive loading of 20 mol% of KOtBu, 92 % conversion of 5 a but a yield of only 74 % of 6 a were obtained. In this case, a white precipitate was obtained which was identified as benzoic acid after acidic workup (see SI, section 6). This observed side reaction might explain the need of higher additive loadings to reach full conversion as well as the difference between conversion and yield. Furthermore, the influence of the cation was investigated by using NaHBEt3 and LiHBEt3 as additives (entries 8 and 9). In comparison to KHBEt3 only a slight decrease in performance was observed with NaHBEt3 whereas LiHBEt3 gave much lower conversion and yield. As control experiments the reaction was performed without any additive (entry 10) as well as without manganese complex 3 g (entry 11) showing only very small reactivity. Lowering of the reaction temperature (entry 12) or catalyst loading (entry 13) led to a decreased catalytic performance. Applying 30 bar of hydrogen pressure only slightly decreased conversion and yield (entry 14).

|

|||||

# |

additive |

Add. load. [mol %] |

Conv. 5 a[b] [%] |

Yield 6 a[b] [%] |

Yield 8 a[b] [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

KHBEt3 |

1.0 |

96(2) |

94(2) |

2(1) |

2 |

KOtBu |

1.0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

KOtBu |

20.0 |

92 |

74[d] |

3[d] |

4 |

KHMDS |

1.0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

5 |

KH |

1.0 |

15 |

5 |

8 |

6 |

KHBEt3 |

0.5 |

70 |

70 |

1 |

7 |

KHBEt3 |

2.0 |

90 |

88 |

4 |

8 |

NaHBEt3 |

1.0 |

91 |

84 |

4 |

9 |

LiHBEt3 |

1.0 |

49 |

31 |

16 |

10 |

none |

– |

0 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

KHBEt3[e] |

1.0 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

KHBEt3[f] |

1.0 |

53 |

49 |

4 |

13 |

KHBEt3[g] |

0.6 |

52 |

50 |

3 |

14 |

KHBEt3[h] |

1.0 |

92 |

91 |

3 |

- [a] General reaction conditions: 1 mmol methyl benzoate 5 a, 5 μmol 3 g (0.5 mol%), 4.0 mL THF, 50 bar H2, 80 °C, 16 h. [b] Conversion of methyl benzoate 5 a and yield of benzyl alcohol 6 a and benzyl benzoate 8 a were determined by GC analysis using hexadecane as internal standard. [c] Average of two experiments given. Values in parentheses represent the standard deviation. [d] Formation of potassium benzoate observed. No tert-butyl benzoate detected via GC analysis. [e] Without complex 3 g. [f] Reaction performed at 60 °C. [g] 3 μmol 3 g (0.3 mol%) used. [h] Reaction performed with 30 bar H2.

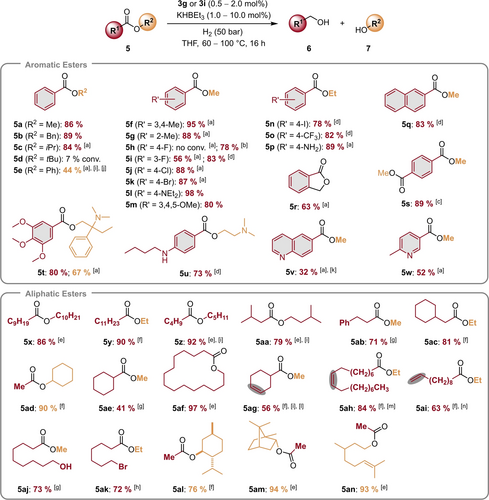

To investigate the scope of the reaction various aromatic and aliphatic esters were exposed to our hydrogenation conditions applying complex 3 g (for aromatic esters) or 3 i (for aliphatic esters) as (pre)catalyst (Scheme 3). Methyl benzoate 5 a and benzyl benzoate 5 b are readily converted to their corresponding alcohols with very good yields. Sterically more hindered isopropyl benzoate 5 c gave the desired product, too, albeit slightly higher temperature and catalyst loading are required, while tert-butyl benzoate 5 d showed low conversion under these conditions. Phenyl benzoate 5 e provided moderate yields of phenol and the formed benzyl alcohol underwent full transesterification to form benzyl benzoate. In this case, we assign the lower conversion to the high acidity of phenol and the formation of phenoxide complexes. In contrast, electron-rich aromatic esters (5 f, 5 g, 5 l, and 5 p) are smoothly converted to their corresponding alcohols. Remarkably, tertiary (5 l) and even primary amines (5 p) are tolerated by this hydrogenation procedure. Notably, alcohols formed from esters with electron-withdrawing groups can inhibit the active catalyst species by the formation of the corresponding alkoxide complexes in a similar manner to phenol mentioned above. Nevertheless, esters 5 h, 5 i, 5 j, 5 k, 5 n and 5 o provided the desired alcohols at somewhat higher temperature and/or higher catalyst loading. Interestingly, halogenated esters displayed varying activity. While methyl p-chlorobenzoate 5 j and methyl p-bromobenzoate 5 k are readily hydrogenated at 100 °C applying 1 mol% of 3 g and 2 mol% KHBEt3, surprisingly, the fluorinated congener 5 h showed no conversion under these conditions. Yet, a fluoro substituent in meta-position (5 i) is tolerated much better, giving the corresponding alcohol in 56 % and with increased catalyst loading even in 83 % isolated yield. Presumably, the fluorinated position is susceptible to nucleophilic aromatic substitution with KHBEt3 or a manganese hydrido complex, which is facilitated by the conjugated ester group. Increasing the loading of KHBEt3 to 10 mol% leads to full conversion for methyl p-fluorobenzoate as well as an isolated yield of 78 % of the alcohol. An iodo substituent (5 n) resulted in lower activity than chloro and bromo substituents, nevertheless, its alcohol was isolated in 78 % yield after applying 2 mol% of 3 g. Furthermore, hydrogenation of the naphthyl ester 5 q gave the corresponding alcohol in good yield. Although lactones and diesters are challenging substrates due to potential side reactions like oligomerization, the corresponding diols from five-membered lactone 5 r and diester 5 s were isolated in good to very good yields. Interestingly, in case of quinoline-derived ester 5 v reduction of either the ester function or the quinoline ring occurred to a similar extent. Here, 37 % of the corresponding alcohol and 20 % of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline-6-carboxylate were isolated. As an example, for heterocyclic esters, the hydrogenation of the niacin-derived ester 5 w proceeded easily and the desired alcohol was isolated in good yield. Similarly, tertiary and secondary amines in the pharmaceutical substrates, trimebutine 5 t and tetracaine 5 u, were well tolerated by our hydrogenation procedure and the corresponding alcohols were isolated in good to very good yield.

Mn-catalyzed hydrogenation of various aromatic and aliphatic esters 5 to their corresponding alcohols 6 and 7. Values below the Lewis structures of esters 5 represent the isolated yields of the corresponding alcohols 6 (red) and/or 7 (orange). Standard conditions: 1 mmol of ester 5, 0.5 mol% 3 g, 1 mol% KHBEt3, 50 bar H2, 4 mL THF, 80 °C, 16 h. [a] 100 °C, 1 mol% 3 g, 2 mol% KHBEt3; [b] 100 °C, 1 mol% 3 g, 10 mol% KHBEt3; [c] 80 °C, 2 mol% 3 g, 4 mol% KHBEt3; [d] 100 °C, 2 mol% 3 g, 4 mol% KHBEt3; [e] 60 °C, 0.5 mol% 3 i, 1 mol% KHBEt3; [f] 80 °C, 1 mol% 3 i, 2 mol% KHBEt3; [g] 100 °C, 1 mol% 3 i, 2 mol% KHBEt3; [h] 100 °C, 2 mol% 3 i, 4 mol% KHBEt3; [i] Yield determined by GC analysis using hexadecane as internal standard; [j] 22 % benzyl benzoate observed by GC analysis. Formed benzyl alcohol undergoes transesterification with phenyl benzoate and liberates phenol, so only 22 % of ester are converted; [k] 20 % methyl 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline-6-carboxylate isolated; [l] 13 % cyclohexylmethanol, 5 % cyclohex-2-enylmethanol, 3 % cyclohex-1-enylmethanol and 5 % methyl cyclohexanecarboxylate observed by GC analysis; [m] The isolated material was an inseparable mixture of regioisomers and diastereomers with an overall (Z) : (E) ratio of 55 : 45 according to GC analysis; [n] 1-undecanol was isolated.

Next, we tested the hydrogenation of various aliphatic esters applying (pre)catalyst 3 i. Esters containing different aliphatic chains (5 x, 5 y, and 5 z) were smoothly hydrogenated already at low temperatures (60 or 80 °C) and low catalyst loadings (0.5 or 1.0 mol%). Sterically more demanding esters containing branched alkyl chains or substituents in closer proximity to the ester group (5 aa, 5 ab and 5 ac) gave slightly lower yields. Steric hindrance appears to be more problematic in R1 than in R2, since cyclohexyl acetate 5 ad was easily hydrogenated whereas methyl cyclohexanecarboxylate 5 ae provided only moderate yield of cyclohexylmethanol. Lactones with larger ring size could be smoothly hydrogenated, e.g. the 16-membered lactone 5 af was converted to the corresponding diol. Interestingly, this catalyst system showed some activity for the hydrogenation of non-activated olefins, which has yet only rarely been observed for homogeneous Mn complexes.11c For example, the internal C=C double bond in 5 ag was partially hydrogenated and next to the ester function in compound 5 ai also the terminal alkene moiety was hydrogenated and undecane-1-ol was isolated in 63 % yield. For the sterically more hindered C=C double bond in citronellyl acetate 5 an, no hydrogenation occurred at the standard conditions and citronellol was isolated in excellent yield. Esters 5 aj and 5 ak containing a hydroxy or a bromide functional group were reduced to their corresponding alcohols with good yields. Furthermore, the natural terpenes menthyl acetate 5 al and bornyl acetate 5 am yielded (±)-menthol and (−)-borneol in 76 % and 94 % yield, respectively.

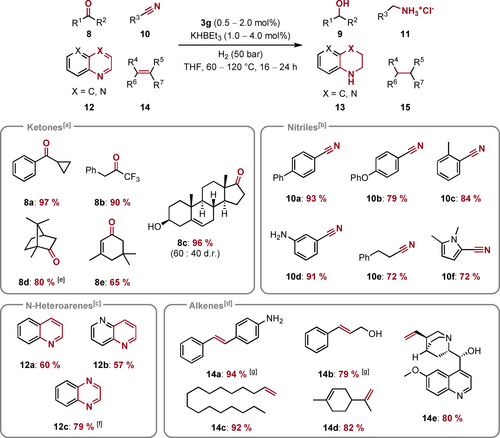

Since we observed the reduction of other moieties like alkenes (5 ae or 5 ag) and N-heteroarenes (5 r) next to ester groups, we were curious about the applicability of our catalytic protocol to other substrate classes. Therefore, we investigated the hydrogenation of ketones 8, nitriles 10, N-heteroarenes 12 and alkenes 14 (Scheme 4). Aromatic and aliphatic ketones are readily converted to the corresponding alcohols (8 a, 8 b, 8 c and 8 d). For the steroid dehydroepiandrosterone 8 c a 60 : 40 mixture of diastereomers was obtained. Interestingly, at temperatures below 60 °C only low activity is observed, which we assign to the energy required for catalyst activation. In case of isophorone 8 e, partial hydrogenation of the conjugated C=C double bond takes place. Moreover, aromatic nitriles with electron-donating groups and aliphatic nitriles (10 a–e) are hydrogenated at 120 °C using 2 mol% of 3 g as (pre)catalysts and were isolated in good to very good yields. Electron-poor nitriles showed only low conversion under these conditions, likely due to catalyst inhibition by substrate coordination. The N-heterocyclic nitrile 10 f is readily converted to the corresponding amine and was isolated in 72 % yield. Additionally, several N-heteroarenes like quinoline 12 a, 1,5-naphtyridine 12 b or quinoxaline 12 c are hydrogenated by the presented catalytic system. Moreover, various alkenes including aromatic (14 a, 14 b) and aliphatic (14 c, 14 d, 14 e) substituents were hydrogenated at 80 °C or 100 °C applying a catalyst loading of 1 mol%. Functional groups such as amines (e.g. in quinine 14 e) and alcohols (e.g. in cinnamyl alcohol 14 b) are readily tolerated by the catalytic procedure. Interestingly, no reduction of the more substituted C=C double bond in limonene 14 d was observed.

Mn-catalyzed hydrogenation of ketones 8, nitriles 10, N-heteroarenes 12 and alkenes 14 to alcohols 9, amines 11, tetrahydro-N-heteroarenes 13 and alkanes 15, respectively. Values below the Lewis structures represent isolated yields. [a] Standard conditions: 1 mmol of ketone 8, 1 mol% 3 g, 2 mol% KHBEt3, 50 bar H2, 4 mL THF, 80 °C, 16 h; [b] Standard conditions: 0.5 mmol of nitrile 10, 2 mol% 3 g, 4 mol% KHBEt3, 50 bar H2, 2 mL THF, 120 °C, 24 h. Corresponding amines were isolated as the hydrochloride salts; [c] Standard conditions: 0.5 mmol of N-heteroarene 12, 2 mol% 3 g, 4 mol% KHBEt3, 50 bar H2, 2 mL THF, 120 °C, 24 h; [d] Standard conditions: 1 mmol of alkene 14, 0.5 mol% 3 g, 1 mol% KHBEt3, 50 bar H2, 4 mL THF, 80 °C, 16 h; [e] 60 °C, 0.5 mol% 3 g, 1 mol% KHBEt3; [f] 1 mol% 3 g, 2 mol% KHBEt3; [g] 100 °C, 1 mol% 3 g, 2 mol% KHBEt3.

Overall, the presented catalytic systems show high efficiency and rank among the best known manganese catalysts for ester hydrogenation.5 In particular, the hydrogenation of various aliphatic esters at only 60 °C and 0.5 mol% catalyst loading is remarkable. The scope is relatively broad and different classes of substrates including ketones, nitriles, N-heteroarenes and, most impressively, alkenes are shown to be hydrogenated efficiently aside from esters. Functional groups like halides, alcohols and tertiary, secondary, and even primary amines are tolerated. However, the high activity as well as the ability to hydrogenate different functional groups results in diminished selectivity in certain cases (substrates 5 v, 5 ag, 5 ah, 5 ai or 8 e). Further limitations of the catalytic system remain heteroaromatic substrates, which are only partially tolerated, as well as lactones with a small ring size.

Mechanistic Investigations

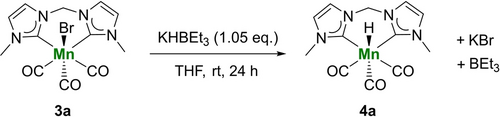

Since the presented catalytic systems represent the first examples of bis(NHC)-based manganese complex catalyzed hydrogenation of carboxylic acid esters, a deeper understanding of the mechanism is important. As a starting point of our mechanistic investigations, hydrido complex 4 a was prepared in almost quantitative yield by the reaction of bromido complex 3 a with one equivalent of KHBEt3 at room temperature over 24 h (Scheme 5). The 1H NMR spectrum of 4 a shows a hydride resonance at −6.79 in THF-d8. The carbonyl vibrations observed by IR spectroscopy are shifted to lower wave numbers (1962, 1866, 1823 cm−1 for 4 a;) in comparison to the corresponding bromido complex (1998, 1917, 1879 cm−1 for 3 a). This observation agrees with the higher electron donation of the hydrido ligand compared to the bromido ligand. Similar shifts between 3 a and 4 a have been found by DFT calculations (SI, section 9.1). As in case of structure 3 a, structure 4 a also exhibits a syn- and anti-conformer, and the former is more stable by 3.84 kcal/mol and should be the major conformer (99.8 %).

Synthesis of bis(NHC) manganese hydrido complex 4 a from bromido complex 3 a with KHBEt3.

Interestingly, hydrido complex 4 a without additive present does not show any catalytic activity in the hydrogenation of methyl benzoate (Table 2, entry 2), but in the presence of complex 4 a and KHBEt3 (entry 3) hydrogenation of methyl benzoate takes place. Obviously, KHBEt3 is not only responsible for formation of hydrido complex 4 a, but also necessary for the catalytic activity. Therefore, we assume that BEt3 liberated during hydrido complex formation plays a crucial role in the catalytic system. A control experiment applying 4 a and BEt3 (entry 4) confirmed this assumption. Also, other borane-based additives have been tested with 4 a and comparable activity was found for 9-borabicyclo(3.3.1)nonane (9-BBN) (see Supporting Information section 11.3 for details). In contrast, the combination of bromido complex 3 a and BEt3 does not catalyze the model reaction (entry 5). Furthermore, the presence of strongly coordinating, monodentate ligands such as CO or PMe3 results in a complete shutdown of the reaction (entries 6 and 7).

|

|||||

# |

[Mn] |

additive |

additive load. [mol %] |

Conv. 5 a[b] [%] |

Yield 6 a[b] [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

3 a |

KHBEt3 |

1.0 |

75(2)[c] |

69(0)[c] |

2 |

4 a |

– |

– |

2(0)[c] |

1(1)[c] |

3 |

4 a |

KHBEt3 |

0.5 |

73 |

64 |

4 |

4 a |

BEt3 |

1.0 |

61(1)[c] |

59(1)[c] |

5 |

3 a |

BEt3 |

1.0 |

0 |

0 |

6[d] |

3 a |

KHBEt3 |

1.0 |

0 |

0 |

7[e] |

3 g |

KHBEt3 |

1.0 |

0 |

0 |

- [a] Reaction conditions: 1 mmol methyl benzoate 5 a, 5 μmol [Mn] (0.5 mol%), 4.0 ml THF, 50 bar H2, 80 °C, 16 h. [b] Conversion of methyl benzoate 5 a and yield of benzyl alcohol 6 a were determined by GC using hexadecane as internal standard. [c] Average of two experiments given. Values in parentheses represent the standard deviation. [d] The autoclave was charged with 10 bar of CO and 50 bar of H2. [e] Reaction was performed in the presence of 5 mol% PMe3.

Moreover, the reaction of 4 a, BEt3 and methyl benzoate (in a 1 : 1 : 2 ratio) was investigated by NMR spectroscopy (see Supporting Information for details), but no transformation was observed after heating the sample at 80 °C for 16 h without H2. However, if the mixture was heated in an autoclave to 80 °C under 50 bar of H2 pressure for 3 h, a clear, light-yellow solution with a blue precipitate was obtained. NMR spectroscopic analysis of the solution confirms quantitative conversion of methyl benzoate to benzyl alcohol and methanol. In addition, the presence of hydrido complex 4 a and another, unidentified manganese complex as well as decomposition of BEt3 to unidentified products is observed (SI section 11). IR analysis of the blue reaction residue shows two absorption bands in the carbonyl area at 1854 and 1781 cm−1, respectively, indicative for an electron-rich manganese species containing only two CO ligands (SI section 11.2). The reaction residue was also tested for catalytic activity in the presence and absence of KHBEt3, but no reaction was observed (SI, section 11.2.2). Therefore, we conclude that the species is not involved in the catalytic cycle.

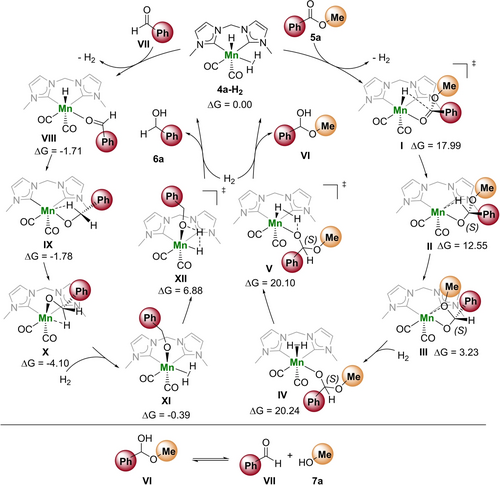

To gain further insight into the mechanism of the hydrogenation of methyl benzoate (5 a), we performed DFT calculations (see Supporting Information for details). Under the H2 rich conditions, we started our computations by substituting one equatorial CO ligand in 4 a by a molecular hydrogen (4 a-H2). However, many attempts to get such a complex via an energetic favourable way failed, either via direct CO dissociation (38.50 kcal/mol) nor OtBu mediated H2 hydrogenolysis (30.96 kcal/mol) as well as BEt3 mediated exchange and CO insertion forming propionaldehyde (29.06 kcal/mol). Therefore, from a computational as well as an experimental perspective, it is unclear how exactly a CO ligand is lost.

Starting from 4 a-H2 and 5 a based on the inner-sphere mechanisms, we found a two-step pathway (Scheme 6). The first step is the Mn−H transfer to the coordinated methyl benzoate via transition state I followed by the formation of a more stable bidentate complex of the formed methoxy(phenyl)methanolate via the C−H and C−OMe exchange (II to III). The second step is the hydrogenolysis of the methoxy(phenyl)methanolate IV via transition state V to methoxy(phenyl)methanol VI as the first intermediate, which is the rate determining step with an apparent Gibbs free energy barrier of 20.24 kcal/mol. Due to the face-coordination of 5 a, we computed the (R)- and (S)-configurations and found that the formation of (S)-methoxy(phenyl)methanol has a lower Gibbs free energy barrier than (R)-methoxy(phenyl)methanol (20.10 vs. 25.12 kcal/mol). Methoxy(phenyl)methanol (VI) can decompose to benzaldehyde (VII) and methanol (7 a). In a similar way, we also computed the hydrogenation of benzaldehyde (VII) following the inner-sphere mechanism. Starting from the complex of benzaldehyde (VIII), it is not possible to locate the corresponding Mn−H transfer transition state and all attempts resulted in the formation of the C−H agostic interacted intermediate IX, which undergoes further isomerisation to intermediate X. Hydrogenolysis via transition state XII results in benzyl alcohol (6 a). As expected, a much lower apparent Gibbs free energy barrier (6.88 kcal/mol, SI) for the hydrogenolysis step (XII) of alkoxide XI has been found.

Mechanistic proposal for the Mn-catalyzed hydrogenation of methyl benzoate. Gibbs free energies (M06L-SCRF) are given in kcal mol−1 and referred to 4 a-H2.

Based on the control experiments, spectroscopic investigations and DFT calculations, we propose the following mechanism: Initially, one CO ligand is cleaved from hydrido complex 4 a to create a vacant coordination site, which is supported by 1) strongly coordinating, monodentate ligands (including strongly coordinating substrates) inhibiting the hydrogenation and 2) the observation of only two CO stretches in the reaction residue. We speculate, that the CO cleavage might be facilitated by BEt3, which was shown to form a catalytically active species with hydrido complex 4 a. However, the detailed role of KHBEt3/BEt3 for the catalytic system is not clear and requires further investigation. Subsequently, substrate coordination to the Mn center occurs, followed by an inner-sphere hydride transfer to the substrate and liberation of the product by hydrogenolysis.

Conclusion

In summary, we present a novel catalytic system for the efficient hydrogenation of carboxylic acid esters based on MnI complexes bearing simple phosphine-free, non-bifunctional bis(NHC) ligands. An improved synthetic access to these bis(NHC) MnI complexes 3 utilizing bis(NHC)-borane adducts has been developed. Complexes 3 have successfully been applied as (pre)catalyst with KHBEt3 as cocatalyst in the hydrogenation of various aromatic and aliphatic esters at low temperatures and low catalyst loadings. The general applicability was further demonstrated by the hydrogenation of other substrate classes such as ketones, nitriles, N-heteroarenes and alkenes. Control experiments reveal the essential role of BEt3 as cocatalyst and indicate an inner-sphere mechanism. This mechanistic proposal is further supported by DFT calculations. Overall, we present rare examples of Mn-based hydrogenation catalysts containing simple phosphine-free, non-bifunctional ligands. We believe that the use of simpler ligand frameworks is a great improvement in the field of homogeneous Mn catalysis.

Author Contributions

N.B. conceptualized the work. H.J., K.J and M.B contributed to the further drafting of the project. N.B. performed synthetic and catalytic experiments for data collection. A.S. measured SC-XRD data and solved molecular structures. H.J. performed DFT calculations. N.B. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. A.S., H.J. and K.J. wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We thank Katja Andres for her support with the syntheses of bis(imidazolium) salts and bis(NHC)-BEt3 adducts. Furthermore, the authors thank Astrid Lehmann for performing elemental analyses, Dr. Marcus Klahn for HRMS measurements, Andreas Koch for VT NMR measurements, and PD Dr. Wolfgang Baumann, Dr. Dilver Peña Fuentes and Susann Buchholz for NMR measurements. We are also grateful to Johannes Fessler for helpful discussions. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.