Development and Validation of a Lecture Assessment Tool for Emergency Medicine Residents

Abstract

Background

Delivering quality lectures is a critical skill for residents seeking careers in academia yet no validated tools for assessing resident lecture skills exist.

Objectives

The authors sought to develop and validate a lecture assessment tool.

Methods

Using a nominal group technique, the authors derived a behaviorally anchored assessment tool. Baseline characteristics of resident lecturers including prior lecturing experience and perceived comfort with lecturing were collected. Faculty and senior residents used the tool to assess lecturer performance at weekly conference. A postintervention survey assessed the usability of the form and the quantity and quality of the feedback. Analysis of variance was used to identify relationships in performance within individual domains to baseline data. Generalizability coefficients and scatterplots with jitter were used to assess inter-rater reliability.

Results

Of 64 residents assessed, most (68.8%) had previous lecturing experience and 6.3% had experience as a regional/national speaker. There was a significant difference in performance within the domains of Content Expertise (p < 0.001), Presentation Design/Structure (p = 0.014), and Lecture Presence (p = 0.001) for first-year versus fourth-year residents. Residents who had higher perceived comfort with lecturing performed better in the domains of Content Expertise (p = 0.035), Presentation Design/Structure (p = 0.037), and Lecture Presence (p < 0.001). We found fair agreement between raters in all domains except Goals and Objectives. Both lecturers and evaluators perceived the feedback delivered as specific and of adequate quantity and quality. Evaluators described the form as highly useable.

Conclusions

The derived behaviorally anchored assessment tool is a sufficiently valid instrument for the assessment of resident-delivered lectures.

The ability to develop and deliver a high-quality lecture is a critical, translatable skill for residents seeking career paths in education, research, and leadership. Previously, our residents received an assessment of their lecturing performance using a 10-point Likert scale as well as qualitative feedback via a preexisting lecture assessment form. This model was perceived by the authors to be insufficient, inconsistent, and unable to appropriately differentiate levels of performance. There are few previously published studies dedicated to the rigorous description of the skills and characteristics of expert lecturers. Copeland and colleagues1 sought to identify and prospectively validate the characteristics of an effective lecture, ultimately identifying three features that predicted overall lecture quality: ability to engage the participants, lecture clarity, and use of a case-based format. Newman and colleagues have previously described the most robust attempt at deriving an assessment tool for peer evaluation of lecture performance.2, 3 The tool derived by Newman and colleagues4 is not ideally suited for the real-time assessment of resident lecturer performance as it lacks space for formative feedback, does not adequately specify observable behaviors across all levels of performance, and spans three pages with 11 “criteria for effective lecturing.” This spurred the desire to develop an assessment tool that could provide specific and timely feedback on resident lecture performance while also effectively discriminating between novice and experienced lecturers.

In 1989 Messick5, 6 set forth a framework for understanding the validity of an assessment tool. As described, there are five major sources of validity for an assessment tool. 1) Content validity, which is the relationship between the content of the assessment and the preexisting literature; 2) response process, which refers to the format of the assessment and quality control of data collection; 3) internal structure, which is the statistical reliability of the test items; 4) relationship to other variables, which refers to the correlation of assessment scores to known external factors; and 5) consequences of testing, which refers to the short and long-term positive and negative impacts of the assessment on both examinees and those administering the test. The objective of this study was to collect and document evidence of validity in these areas for a novel behaviorally anchored lecture assessment tool.

Methods

Using a nominal group consensus building technique the study authors derived the lecture assessment tool.7 The consensus-building panel was composed of five clinician educators with a combined 22 years of experience in resident education and 11 years in residency program directorship, two individuals with formal training in medical education, and one chief resident within the residency training program. The panel members performed independent literature reviews prior to the first consensus meeting. A research librarian was also consulted to aid in the identification of previously published lecture assessments as well as literature describing the components of an effective lecturer. During the first of a series of three in-person meetings the panel focused on arriving at 100% consensus on the broad domains of performance (Goals and Objectives, Content Expertise, Audience Engagement, Presentation Design, and Lecture Presence). During subsequent meetings, the panel specified observable and characteristic behaviors for five levels of performance within each domain, ultimately arriving at the final assessment tool.8 The panel members piloted the evaluation tool for the first two months of the 2014 academic year. Qualitative feedback on the usability of the form was solicited via e-mail and the comments were used to make iterative changes to the tool prior to the official deployment.

A preintervention survey was used to record the baseline characteristics of resident lecturers. For each resident-given lecture from September 1, 2014, to June 30, 2016, a printed copy of the lecture assessment was distributed to two faculty members and one fourth-year emergency medicine resident. The evaluators completed the assessment tool during the course of the resident lecture. Evaluators were trained on the use of the form by means of a brief e-mail communication prior to the start of the study period. The forms were collected following each lecture, performance data were entered into a REDCap9 database, and the forms were given to the resident lecturers to keep for their review and records. Immediately following the study period, a postintervention survey assessing the usability of and the quality of the feedback provided by the form was distributed to both evaluators and resident lecturers.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp.), R Version 3.2.5 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), and SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute). To identify relationships between performance in individual domains and baseline data we used one-way analysis of variance with a simple Bonferroni correction or independent-samples t-tests. With the method described by Putka and colleagues,10 generalizability coefficients were calculated for every lecture that had at least two ratings. We also graphically assessed inter-rater relationships using scatterplots with jitter. This study was reviewed by the institutional review board (IRB) and determined to be exempt from IRB review in accordance with 45 CFR 46.101(b).

Results

There were 64 resident lecturers and 39 evaluators included in the study. The baseline characteristics of the 64 resident lecturers included in the study are shown in Table 1. Nearly all participants had a baseline perceived comfort with lecturing rated between 2 and 4 on a 5-point scale (with 1 lowest and 5 highest). Few residents had significant preexisting lecturing experience with only 12 of 64 residents (19%) identifying frequent or regional/national-level lecturing experiences.

| Characteristics | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (±SD) | 29 | (±2) |

| Additional baseline characteristics | ||

| Male | 45 | (70.3) |

| Postgraduate year of training | ||

| PGY-1 | 26 | (40.6) |

| PGY-2 | 13 | (20.3) |

| PGY-3 | 14 | (21.9) |

| PGY-4 | 11 | (17.2) |

| Graduate or professional degrees in addition to MD | 8 | (12.5) |

| MS | 3 | (37.5) |

| PhD | 2 | (25.0) |

| MBA | 2 | (25.0) |

| MPH | 1 | (12.5) |

| Previous lecturing/public-speaking experience | ||

| Rare | 8 | (12.5) |

| Occasional | 44 | (68.8) |

| Frequent | 8 | (12.5) |

| Invited as a regional or national speaker | 4 | (6.3) |

| Current comfort level with lecturing/public-speaking | ||

| 1—Completely uncomfortable | 3 | (4.7) |

| 2 | 15 | (23.4) |

| 3 | 27 | (42.2) |

| 4 | 17 | (26.6) |

| 5—Completely comfortable | 2 | (3.1) |

| Current perception of skills as a lecturer | ||

| Novice lecturer | 12 | (18.8) |

| Some lecturing skills/significant areas for improvement | 30 | (46.9) |

| Good lecturing skills/small areas for improvement | 21 | (32.8) |

| Excellent lecturing skills/rare performance issues | 1 | (1.6) |

| Expert lecturing skills/confident giving any lecture | 0 | (0.0) |

Internal Structure

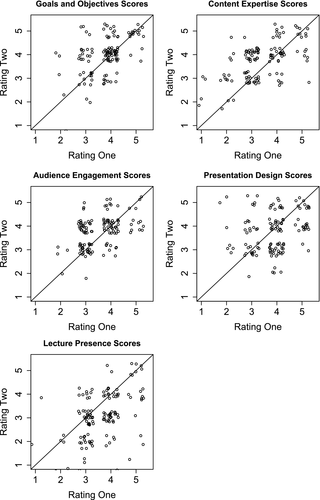

There were 307 evaluations by 60 different evaluators for 123 lectures given by 57 different residents. Ten evaluations that were missing a lecture topic were excluded from analysis. Generalizabilty coefficients for the five domains showed fair inter-rater agreement in the domains of Content Expertise (G = 0.47), Presentation Design (G = 0.48), Audience Engagement (G = 0.45), and Lecture Presence (G = 0.53; Table 2). Inter-rater agreement for the domain of Goals and Objectives was poor (G = 0.20). Scatterplots with jitter for all of the domains are shown in Figure 1 and show close clustering of scores for all domains except Audience Engagement.

| Assessment Category | Generalizability Coefficient | q | k | Variance Components | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratee | Rater | Ratee × Rater | ||||

| Goals | 0.198 | 0.501 | 1.882 | 0.075 | 0.110 | 0.472 |

| Expertise | 0.468 | 0.471 | 1.984 | 0.147 | 0.023 | 0.310 |

| Design | 0.482 | 0.480 | 1.954 | 0.169 | 0.129 | 0.233 |

| Engage | 0.445 | 0.491 | 1.910 | 0.284 | 0.284 | 0.412 |

| Presence | 0.529 | 0.472 | 1.984 | 0.253 | 0.080 | 0.372 |

Relationships to Other Variables

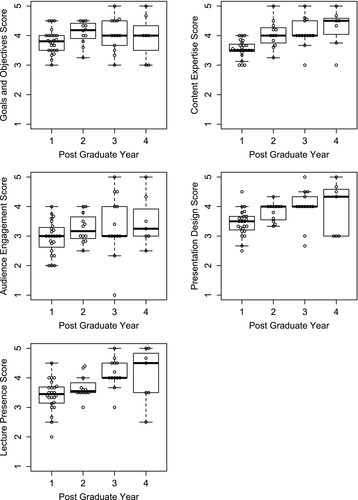

In general, more senior level residents had higher performance in the domains of Content Expertise (p < 0.001), Presentation Design (p = 0.014), and Lecture Presence (p = 0.001) compared to more junior residents (Figure 2). Those residents with higher baseline perceived comfort level with lecturing had significantly higher performance in the domains of Content Expertise (p = 0.035), Presentation Design (p = 0.037), and Lecture Presence (p < 0.001). There was also significantly better performance in all domains for “morbidity and mortality” (M&M) case conferences (given by chief residents) and fourth-year resident “Capstone Lectures” compared to all other lectures (Table 3).

| Assessment Category | M&M/Capstone Lectures | Other Lectures | Difference | p-value | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Lower | Upper | |||

| Goals & objectives | 4.29 | 0.66 | 3.83 | 0.67 | –0.457 | 0.012 | –0.81 | –0.10 |

| Content expertise | 4.38 | 0.56 | 3.68 | 0.57 | –0.704 | <0.0001 | –1.02 | –0.39 |

| Presentation design/structure | 4.13 | 0.72 | 3.59 | 0.62 | –0.539 | 0.002 | –0.88 | –0.20 |

| Audience engagement | 3.97 | 0.86 | 3.10 | 0.82 | –0.874 | <0.0001 | –1.31 | –0.44 |

| lecture presence | 4.32 | 0.71 | 3.58 | 0.70 | –0.741 | <0.0001 | –1.11 | –0.37 |

- M&M = morbidity and mortality.

Evidence Based on Consequences of Testing

There were 65 responses to the postintervention survey (26 lecturers, 17 evaluators, and 22 who were both lecturers and evaluators). Of the 48 lecturers who responded, 44 (92%) described the feedback provided by the form as specific. The quality of the feedback provided was described as adequate to excellent in quality by 45 (94%) lecturers. In addition, 44 (92%) lecturers perceived the quantity of feedback to be adequate to more than expected. All evaluators felt the form allowed them to provide at least somewhat specific feedback. The quality of the feedback able to be provided was described as adequate to excellent by all evaluators. Of the 39 evaluators, 38 (97%) perceived the quantity of the feedback to be adequate to more than expected. In assessing the usability of the form, 35 (92%) evaluator respondents were able to fill out the form completely during the course of the resident lecture and 34 (87%) evaluators indicated that the form was highly usable.

Discussion

We present evidence for the validity of a behaviorally anchored assessment tool for resident-delivered lectures using Messick's validity framework.5, 6

Content Validity

Content validity refers to the relationship between the content of the assessment and the preexisting literature and is dependent on the robustness of the derivation process. As evidence of the content validity for this lecture assessment form, the derivation was performed using a nominal group consensus-building methodology. The consensus panel possessed a broad base of experience in resident medical education and included a resident stakeholder. This allowed for the incorporation of the viewpoints of the subject of evaluation as well as the evaluators. The derivation process included a literature search conducted simultaneously by all members of the consensus panel and done with the consultation of a clinical informationist. The derived lecture assessment tool is a new implementation and organization of previously published literature describing the qualities of effective lecturers.

Response Process

Response process refers to the format of the assessment and quality control of data collection. The format of the derived lecture assessment tool is immediately familiar to resident learners as behaviorally anchored assessment tools are used broadly in medical education (Step 2 Clinical Skills Examination,11 ACGME Milestone Evaluations,12 and the National Clinical Assessment Tool for Medical Students in the Emergency Department13). The derived form has clearly defined observable behaviors for all levels of performance in each domain, readily allowing for the rapid identification of a level of performance of a lecturer by the evaluator.

Internal Structure

Internal structure refers to the statistical reliability of the test items. This assessment tool displays fair agreement for four of five domains. We posit the poor agreement in the domain of goals and objectives may be due to the presence of a number of lectures built on a “case follow-up” format, where the formal stating of goals and objectives at the beginning of a lecture is uncommon. In fact, in this lecture format, the learning objectives may be diffused and implied throughout the lecture and may never be formally delineated. A graphical review of the data through scatterplots with jitter shows that, for those lectures with more than one evaluation, the majority of evaluations tend to fall within one level of performance of one another. Desiring to have the assessment form be as easy to implement as possible, we intentionally limited the intensity of training to a series of e-mail communications. With limited formal training prior to its implementation, this form displays an acceptable level of reliability for a low-stakes evaluation. It would be expected that more rigorous training would result in improved agreement.

Relationship to Other Variables

Relationship to other variables refers to the correlation of assessment scores to known external factors. Prior to the start of the study, we hypothesized that a valid assessment would show improved performance for lecturers with greater preexisting lecturing experience and higher perceived comfort with lecturing. We also hypothesized improved performance by senior residents in comparison to junior residents and higher performance for the lecture types delivered by our most senior residents. In examining the relationship between performance on the assessment and other variables, we found significantly higher performance in all domains for the lecture types delivered by our most senior residents. We also found higher performance in multiple domains for senior residents and for those residents with higher baseline perceived comfort with lecturing. M&M conferences, delivered by our chief residents, and Capstone Lectures, delivered by our fourth-year residents are widely considered to be the best delivered and structured lectures given by our residents. This evaluation form was able to effectively capture this, finding a statistically significant improved performance for these lectures compared to all other resident lectures.

Evidence Based on the Consequences of Testing

Evidence based on consequences of testing refers to the short- and long-term positive and negative impacts of the assessment on both examinees and those administering the test. The data we gathered in this domain of validity specifically focused on the short-term consequences of using the form. We found that the form is highly usable, able to be filled out during the course of even brief resident lectures, and able to be deployed with a minimum of training while still providing high-quality, specific feedback.

There is the potential for significant long-term benefits to using this form. As a valid assessment, it can effectively document the lecturing ability of a resident and would be expected to show improvement in lecturing performance over time. As such, this assessment tool has the potential to be a powerful component of a resident's teaching portfolio. In addition, the form has the potential to be a powerful educational tool. We have found that residents receiving these evaluation forms have begun to “teach to the form” by including more interactive and engaging lecturing methods (small group breakouts, buzz groups, directed questioning).

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. This was a single-site study and it is not known whether performance on this form will be replicable in different training environments. The inter-rater reliability of the assessment tool was likely limited due to a limited amount of training on the use of the assessment. Another potential limitation of the study is that three of the study authors contributed to >20% of the total number of evaluations completed due to their role in the program leadership. As study authors, they were aware of the objectives of the study and reviewers, in general, were not blinded to the level of training of the residents delivering the lectures. However, when controlling for these frequent raters there was no impact on generalizability coefficients.

Conclusions

The derived behaviorally anchored assessment has sufficient evidence for validity for its use as a tool as a low-stakes assessment of resident-delivered lectures. In addition, it is able to provide timely and high-quality feedback on lecturing performance.