The Effect of Unemployment on Food Spending and Adequacy: Evidence from Coronavirus-Induced Firm Closures

Funding information: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service

Abstract

We estimate the impact of involuntary unemployment following employer shutdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic on American households' past-week food expenditures, free food receipt, and food sufficiency, as well as confidence about next month's food adequacy. Over April to June 2020, compared with households containing employed respondents, households with respondents who lost their jobs due to coronavirus-induced firm closures spent 15% less on food, were 36% more likely receive free food, were 10% less likely to have enough food to eat, and were 21% less likely to report at least moderate confidence in their future ability to afford needed foods.

JEL CLASSIFICATION

I12; J21; J63

On March 11, 2020 the World Health Organization declared the spread of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) a pandemic, and on March 13, 2020 President Donald J. Trump declared a national emergency to combat the spread and various effects of the coronavirus in the United States. Many Americans have lost their jobs and suffered losses in employment income in their households, which are likely to have a multitude of social and economic impacts on American families throughout the nation. For example, in April 2020, the unemployment rate increased by 10.3 percentage points to 14.7%, the highest rate and the largest over-the-month increase in the history of the series (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020). Also, to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, most states issued stay-at-home orders and ordered temporary shutdowns of business establishments deemed nonessential, which disproportionately affected workers in lower paying jobs (Dey & Loewenstein, 2020).

One of the most important determinants of a household's food security status is the level of financial resources available to the household (Gundersen et al., 2011; Gundersen & Gruber, 2001). Major economic downturns can thus lead to adverse food intake patterns and diet-related health outcomes. The prevalence of household food insecurity rose sharply during the Great Recession of 2007–2009 (Gundersen & Ziliak, 2018; Ziliak, 2020) and fell below the pre-recession 2007 level for the first time in 2019 (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2020).1 Non-representative Internet survey data show that the percentage of food-insecure households in May 2020 was roughly similar to the level seen during the Great Recession (Ahn & Norwood, 2020), whereas nationally representative survey data show that food insecurity among non-elderly adults increased to its highest ever recorded level (20.9%) in March/April 2020 (Waxman et al., 2020). Using nationally representative data, Ziliak (2020) estimates that, among non-elderly adults, during the COVID-19 pandemic the food insufficiency rate has tripled compared to 2019 and more than doubled relative to the Great Recession.

In this study, we estimate the impacts that coronavirus-induced unemployment has had on household food spending, free food receipt, food sufficiency, and confidence about the future ability to afford food during the coronavirus pandemic. It builds on recent work that seeks to identify the causal effect of unemployment resulting from firm closures on measures of health-related economic hardship. Studies addressing the effect of involuntary job loss on health have found harmful effects on outcomes such as overweight and obesity (Deb et al., 2011), physical health scores (Schiele & Schmitz, 2016), mental health (Cygan-Rehm et al., 2017; Marcus, 2013), blood glucose levels (Michaud et al., 2016), and hospitalization and mortality (Browning & Heinesen, 2012; Eliason & Storrie, 2009). Due in part to the rapidity with which the COVID-19 pandemic affected the U.S. economy, direct effects on many of such outcomes is not possible. However, using data collected in “real time” (described below), we examine how job loss has affected indexes of health and material hardship. Although measures of spending and food sufficiency are not themselves health indicators, they point to future dynamics in latent health status (Li Donni, 2019). Because a firm closure caused by the coronavirus pandemic is completely outside the control of individuals, we argue that, conditional on a wide variety of characteristics we are able to observe, our analysis provides causal estimates of the effects of unemployment on important health-related outcomes. Thus, our findings are especially relevant for local, state, and federal decision makers regarding food assistance or more general income support programs, especially during a pandemic such as the one being experienced throughout the world.

The rest of the paper unfolds as follows. We first describe the data sets used in the analysis. Second, we outline the empirical strategy we employ to identify causal impacts of unemployment on diet-related outcomes. Third, we discuss our main results, which are followed by a discussion of robustness checks. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of the policy implications of the study.

DATA

To help understand the social and economic impacts of COVID-19 on American households, the U.S. Census Bureau developed the Household Pulse Survey (HPS) in partnership with five federal statistical partner agencies: Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Center for Health Statistics, USDA's Economic Research Service, National Center for Education Statistics, and Department of Housing and Urban Development. The sampling frame is built on a master address file that matches physical addresses to email addresses and phone numbers. Weekly data collection began on April 23, 2020 through an online platform used by the U.S. Census Bureau (Qualtrics), and Phase 1 of the HPS continued through the end of July.2

Our analysis uses data from the first data collection period (April 23 to May 5) through the eighth data collection period (June 18–23). Our diet-related dependent variables are (a) total household food spending in the past seven days, (b) household spending on prepared meals from outside establishments (FAFH) in the past seven days, (c) household spending on food to prepare and eat at home (FAH) in the past seven days, (d) household receipt of free groceries or meals in the past seven days, (e) household food sufficiency in the past seven days, and (f) confidence about being able to afford the kinds of food the household needs in the next four weeks.3 Because we are interested in the estimation of causal impacts of unemployment on these dietary outcomes, our analysis focuses on households containing individuals eighteen and older who either (a) reported working for pay or profit in the past seven days (“employed”) or (b) reported that their main reason for not working for pay or profit in the past seven days was because their place of employment closed temporarily due to the coronavirus pandemic or went out of business due to the coronavirus pandemic (“unemployed due to a firm closure”). In order to obtain household-level descriptive statistics and regression estimates, in all analyses we weight observations by the person-level HPS sampling weight divided by the number of adults in the household (hereafter called the “HPS household-level sampling weight”).

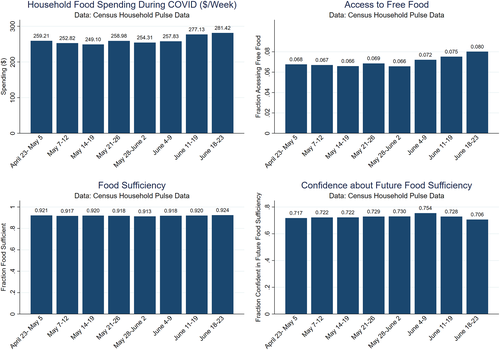

Figure 1 shows the evolution of households' total food spending, access to free food, food sufficiency, and confidence about future ability to afford needed foods over our analysis period. For each variable, there is variation in levels across the weeks of the survey. Total food spending dipped in the early weeks and then rose toward the end of the analysis period. Free food receipt was stable early on and then showed an increasing trend toward the end. Food sufficiency rates were relatively stable during the entire sample period. Confidence about future ability to afford needed foods showed a slightly increasing trend early on followed by a dip toward the end of the sample period.

Note: Observations are weighted by the Household Pulse Survey household-level sampling weight

[Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]In Table 1, summary statistics for the overall sample, employed sample, and unemployed sample are provided for the dependent variables as well as a wide variety of explanatory variables. As expected, there are some differences in demographic characteristics by employment status because coronavirus' impact on business closure decisions partly depends on a worker's ability to work from home, and extant data show that telework participation varies across American workers by demographic group (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019). Although even Americans with postsecondary schooling and high household incomes have been affected, the vast majority of Americans unemployed due to a firm closure have less education and lower household incomes. For example, 46.4% of households affected by such an employment shock contain a respondent who attained a high school degree or less, whereas 21.2% contain a respondent who holds a bachelor's degree or more. Although 12.8% of households affected by a coronavirus-induced business closure reported having a household income of at least $100,000 in 2019, 60.2% reported having a household income of less than $50,000. These patterns show that the exogenous coronavirus-induced unemployment shock has had impacts throughout the entirety of U.S. society, especially among less advantaged households.

| All | Employed | Unemployed due to firm closure | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | Mean | |

| (St. dev.) | (St. dev.) | (St. dev.) | |

| Dependent variables | |||

| Total food spending ($) | 261.354 (190.714) | 262.776 (187.863) | 247.432 (216.155) |

| FAFH spending ($) | 73.438 (86.719) | 74.420 (85.628) | 63.826 (96.225) |

| FAH spending ($) | 187.916 (138.757) | 188.356 (137.107) | 183.607 (153.907) |

| Received free food | 0.070 | 0.065 | 0.118 |

| Enough food | 0.919 | 0.932 | 0.791 |

| Confident in future ability to afford food | 0.728 | 0.753 | 0.478 |

| Explanatory variables | |||

| Respondent characteristics | |||

| Log(number of kids) | 0.524 (0.691) | 0.524 (0.690) | 0.526 (0.705) |

| Log(number of adults) | 1.452 (0.380) | 1.451 (0.377) | 1.461 (0.410) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 0.526 | 0.537 | 0.413 |

| Male | 0.509 | 0.517 | 0.431 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 0.146 | 0.143 | 0.182 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.111 | 0.106 | 0.160 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian/other | 0.090 | 0.088 | 0.105 |

| Age | 44.357 (14.003) | 44.212 (13.807) | 45.776 (15.720) |

| Educational attainment | |||

| High school graduate | 0.253 | 0.241 | 0.368 |

| Some college | 0.206 | 0.203 | 0.232 |

| Associate's degree | 0.095 | 0.095 | 0.092 |

| Bachelor's degree and above | 0.394 | 0.413 | 0.212 |

| Household income | |||

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 0.185 | 0.186 | 0.171 |

| $75,000 to $99,999 | 0.142 | 0.146 | 0.100 |

| $100,000 to $149,999 | 0.169 | 0.178 | 0.082 |

| $150,000 and above | 0.162 | 0.174 | 0.045 |

| General health status | |||

| Fair or poor | 0.116 | 0.109 | 0.185 |

| Tenure | |||

| Own home | 0.638 | 0.650 | 0.517 |

| State-level movement trends (relative to Jan. 3 to Feb. 6, 2020) | |||

| Retail and recreation | −23.462 (14.247) | −23.060 (14.183) | −27.397 (14.275) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | −2.670 (7.925) | −2.491 (7.914) | −4.426 (7.821) |

| Parks | 43.779 (58.025) | 44.829 (58.367) | 33.507 (53.486) |

| Transit stations | −33.826 (17.585) | −33.419 (17.620) | −37.805 (16.723) |

| Workplaces | −40.877 (7.251) | −40.694 (7.212) | −42.661 (7.383) |

| Residential | 15.051 (4.389) | 14.935 (4.371) | 16.176 (4.399) |

| Sample size | 377,264 | 351,106 | 26,158 |

- Note: These are summary statistics for the regression sample involving total food spending. Observations are weighted by the Household Pulse Survey household-level sampling weight.

The response to the arrival of the coronavirus was heterogeneous across states, and state-specific policy responses may be correlated with how food-related behavior was impacted by coronavirus-induced unemployment. In order to account for these differences, we include in our vector of regressors measures of how visits to various categories of places (retail and recreation, grocery and pharmacy, parks, transit stations, workplaces, and residential) changed in a given state over the sample period, relative to a baseline value for that day of the week. In particular, these data capture visits for each day compared to the median value for the corresponding day of the week during a fixed pre-pandemic period (five-week period from January 3 to February 6, 2020; Google LLC, 2020). In the regression analysis, we use the state-specific value for the first day in each survey data collection period (e.g., the value for April 23 is used for the HPS survey period April 23 to May 5). As expected, in the two months after the arrival of the coronavirus, visits to non-residential indoor places where it can be difficult to socially distance fell (i.e., retail and recreation, grocery and pharmacy, transit stations, and workplaces), while visits to non-residential outdoor places where it is easier to socially distance (i.e., parks) and visits to residences rose.

EMPIRICAL STRATEGY

The arrival of the coronavirus in the U.S. was exogenous and unpredictable, but it is important to emphasize that it was not a randomly distributed shock across workers. It is possible that, even in such extraordinary circumstances, some employers choose to lay off the worst-performing workers first, followed by more productive workers. Because we are interested in estimating causal effects of unemployment, we compare diet-related outcomes of employed persons to those who lost their jobs due to a completely exogenous reason—firm closures brought on by the coronavirus pandemic. Importantly, individuals who reported being unemployed for a reason other than a coronavirus-induced business shutdown are not included in the analysis because they could have selected into unemployment for reasons that may be correlated with food-related behaviors. By contrast, individuals who became unemployed due to a firm closure would likely still be employed if the spread of COVID-19 had not significantly disrupted business operations. In particular, we argue that, conditional on our worker-level observables, the coronavirus randomizes workers into the treatment (unemployment) in a way that is unconfounded by selection.

In estimating Equation 1, the parameter α1 measures the average impacts of being unemployed due to a firm closure. In order to account for the HPS sampling design, as noted above, the regression analyses are weighted by the HPS household-level sampling weight. To allow for arbitrary correlation among observations from the same state, standard errors are clustered at the state level. Because we are testing for effects of unemployment on several diet-related outcomes, following Anderson (2008), we also calculate q-values associated with the unemployment indicator in order to account for multiple hypothesis testing, where q-values are calculated considering all food-related variables as a single outcome family.

RESULTS

To help interpret the estimates produced by Equation 1, we begin by estimating a version of Equation 1, where the dependent variable is an indicator for whether the respondent's household has experienced a loss of employment income (overall sample mean = 44.1%) since March 13, 2020—the day President Donald J. Trump declared a national emergency to combat the spread of COVID-19. We find that unemployment due to a firm closure increases the likelihood of a household-level employment income loss by 47.3 percentage points or 107% relative to the overall sample mean. Although we cannot estimate the average size of the income shock, it is clear that the vast majority of households containing respondents who are unemployed due to a firm closure suffered from a recent loss of employment income in the household.

Consistent with such a negative household-level income shock, we find strong and consistent evidence that unemployment due to a firm closure negatively affected diet-related outcomes over the study period. In Table 2, we show that it reduced households' food spending, food sufficiency, and confidence about future ability to afford needed foods, as well as increased free food receipt.5 The estimated effects are all large in magnitude relative to overall sample means and are statistically significant at conventional levels. Compared with households with an employed respondent, we find that households' total food spending is 15.0% lower, likelihood of free food receipt is 35.7% higher, likelihood of being food sufficient is 9.5% lower, and likelihood of being at least moderately confident about being able to afford needed foods in the future is 21.0% lower among households with a respondent who is unemployed due to a firm closure.6 The total food spending difference is mostly driven by FAFH spending, with households containing a respondent who is unemployed due to a firm closure spending 44.8% (8.5%) less than did households with an employed respondent on FAFH (FAH) in the past seven days. All of these results hold firm when accounting for multiple hypothesis testing (q-values all below 0.01).

| AS (Total food spending) | AS (Total FAFH spending) | AS (Total FAH spending) | Received free food | Enough food | Confident in future ability to afford food | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployed due to firm closure | −0.163*** | −0.598*** | −0.089*** | 0.025*** | −0.087*** | −0.153*** |

| (0.025) | (0.049) | (0.029) | (0.005) | (0.009) | (0.008) | |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| q-value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Effect size relative to sample mean | −15.0% | −44.8% | −8.5% | 35.7% | −9.5% | −21.0% |

| Individual characteristics | ||||||

| Log(number of kids) | 0.256*** | 0.160*** | 0.309*** | 0.061*** | −0.020*** | −0.043*** |

| (0.009) | (0.014) | (0.010) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.004) | |

| Log(number of adults) | 0.437*** | 0.479*** | 0.498*** | 0.027*** | −0.021*** | −0.059*** |

| (0.018) | (0.031) | (0.015) | (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.005) | |

| Married | 0.074*** | 0.021 | 0.104*** | −0.004 | 0.015*** | 0.010** |

| (0.012) | (0.021) | (0.015) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.004) | |

| Male | 0.058*** | 0.151*** | 0.025** | −0.014*** | 0.004 | 0.023*** |

| (0.009) | (0.021) | (0.010) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Hispanic | 0.209*** | 0.443*** | 0.174*** | 0.033*** | −0.005 | −0.073*** |

| (0.021) | (0.031) | (0.023) | (0.003) | (0.006) | (0.008) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.160*** | 0.423*** | 0.081*** | 0.017*** | −0.057*** | −0.125*** |

| (0.026) | (0.053) | (0.029) | (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.009) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian/other | 0.048*** | 0.058 | 0.01 | 0.004 | −0.005 | −0.047*** |

| (0.015) | (0.035) | (0.021) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.008) | |

| Age | 0.007*** | 0.003 | 0.010*** | 0.001* | −0.002*** | −0.014*** |

| (0.002) | (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Age squared | −0.000*** | −0.000*** | −0.000*** | −0.000* | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| High school graduate | −0.104** | −0.201* | −0.057 | −0.030*** | 0.055*** | 0.066*** |

| (0.047) | (0.106) | (0.035) | (0.009) | (0.013) | (0.016) | |

| Some college | −0.165*** | −0.334*** | −0.107*** | −0.034*** | 0.075*** | 0.093*** |

| (0.047) | (0.108) | (0.034) | (0.009) | (0.013) | (0.017) | |

| Associate's degree | −0.182*** | −0.335*** | −0.136*** | −0.035*** | 0.087*** | 0.111*** |

| (0.042) | (0.102) | (0.035) | (0.009) | (0.013) | (0.017) | |

| Bachelor's degree and above | −0.200*** | −0.473*** | −0.143*** | −0.037*** | 0.104*** | 0.184*** |

| (0.045) | (0.102) | (0.032) | (0.009) | (0.013) | (0.015) | |

| Household income $50,000 to $74,999 | 0.141*** | 0.240*** | 0.123*** | −0.033*** | 0.061*** | 0.114*** |

| (0.024) | (0.038) | (0.025) | (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.008) | |

| Household income $75,000 to $99,999 | 0.217*** | 0.413*** | 0.170*** | −0.046*** | 0.081*** | 0.172*** |

| (0.021) | (0.044) | (0.025) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.007) | |

| Household income $100,000 to $149,999 | 0.302*** | 0.484*** | 0.266*** | −0.058*** | 0.083*** | 0.216*** |

| (0.024) | (0.048) | (0.030) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.006) | |

| Household income $150,000 and above | 0.459*** | 0.754*** | 0.403*** | −0.080*** | 0.077*** | 0.261*** |

| (0.027) | (0.072) | (0.026) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.006) | |

| Fair or poor general health status | −0.088*** | −0.148*** | −0.106*** | 0.010** | −0.126*** | −0.199*** |

| (0.013) | (0.023) | (0.018) | (0.004) | (0.008) | (0.005) | |

| Own home | −0.029** | −0.080*** | −0.002 | −0.013*** | 0.040*** | 0.057*** |

| (0.012) | (0.022) | (0.017) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.006) | |

| State-level movement trends (relative to Jan. 3 to Feb. 6, 2020) | ||||||

| Retail and recreation | 0.000 | 0.002 | −0.000 | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.002* |

| (0.002) | (0.006) | (0.003) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Grocery and pharmacy | −0.002 | 0.013* | −0.005* | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.002** |

| (0.003) | (0.007) | (0.003) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Parks | −0.000 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000* | −0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Transit stations | 0.001 | −0.004 | 0.000 | −0.002* | 0.000 | 0.002* |

| (0.002) | (0.005) | (0.003) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Workplaces | −0.003 | −0.008 | 0.005 | 0.005*** | −0.000 | −0.001 |

| (0.005) | (0.015) | (0.006) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.002) | |

| Residential | 0.001 | −0.003 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.003** | 0.002 |

| (0.010) | (0.019) | (0.010) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| R-squared | 0.139 | 0.075 | 0.106 | 0.063 | 0.138 | 0.224 |

| N | 377,264 | 378,977 | 380,408 | 385,936 | 385,911 | 386,064 |

- Note: Each regression is weighted by the Household Pulse Survey household-level sampling weight. Standard errors clustered at the state of residence level are in parentheses. Other controls included but not shown: dummies for survey week and dummies for state of residence.

- Abbreviations: AS, arsinh or inverse hyperbolic sine; FAFH, food away from home; FAH, food at home.

Robustness checks

Time-varying heterogeneity within states over time

In our regression analysis, we include state fixed effects in our vector of regressors, which control for all permanent differences across states. Even though our analysis period is relatively short (April 23 to June 23), one may argue that this period is a very dynamic one, with many changes occurring within states over time. For example, policy responses to the spread of COVID-19 have varied not only across but also within states over time. Of course, these factors are of concern if they are related to both unemployment and our dietary outcome variables, and are not well captured by the vector of state-specific movement trends across the different categories of places shown in Table 1. We address this potential concern by augmenting our main estimation equation with state-specific linear time trends (Table A1) and state-specific quadratic time trends (Table A2). We find that controlling for unobserved state-level factors that move in a linear or nonlinear fashion within states over time barely change the estimated effects of unemployment. Thus, it is unlikely that our estimates are subject to omitted variable bias caused by time-varying heterogeneity that varies within states over time.

Alternate control group

As mentioned above, a substantial share of the respondents who were involuntarily displaced due to a business closure were from households with incomes below $50,000. Although we control for a rich set of characteristics, including household income, one may be concerned that our conclusions are driven by our choice of the control group (all employed respondents in the data). We explore this by running our main specification, excluding all respondents from households with incomes of at least $50,000 (Table 3). Although the magnitudes of the coefficient estimates slightly differ from those shown in Table 2, which is expected due to the difference in the counterfactual group, the effect sizes and conclusions are very similar to those from the main analysis.

| AS(Total food spending) | AS(Total FAFH spending) | AS(Total FAH spending) | Received free food | Enough food | Confident in future ability to afford food | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployed due to firm closure | −0.211*** (0.034) | −0.621*** (0.079) | −0.114*** (0.040) | 0.038*** (0.008) | −0.100*** (0.011) | −0.139*** (0.010) |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| q-value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Effect size relative to sample mean | −19.0% | −46.3% | −10.8% | 32.7% | −12.1% | −26.5% |

| Individual characteristics | ||||||

| Log(number of kids) | 0.303*** (0.017) | 0.179*** (0.024) | 0.360*** (0.019) | 0.073*** (0.006) | −0.028*** (0.006) | −0.050*** (0.007) |

| Log(number of adults) | 0.408*** (0.027) | 0.453*** (0.033) | 0.444*** (0.023) | 0.026*** (0.008) | −0.026*** (0.007) | −0.055*** (0.010) |

| Married | 0.083*** (0.026) | 0.026 (0.048) | 0.102*** (0.026) | −0.011* (0.006) | 0.029*** (0.006) | 0.017 (0.010) |

| Male | 0.045** (0.019) | 0.187*** (0.038) | −0.001 (0.021) | −0.020*** (0.006) | 0.005 (0.005) | 0.039*** (0.008) |

| Hispanic | 0.336*** (0.027) | 0.561*** (0.045) | 0.300*** (0.028) | 0.043*** (0.006) | −0.002 (0.012) | −0.083*** (0.012) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.299*** (0.038) | 0.617*** (0.065) | 0.202*** (0.040) | 0.012 (0.012) | −0.076*** (0.009) | −0.128*** (0.013) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian/other | 0.204*** (0.043) | 0.323*** (0.086) | 0.122** (0.050) | −0.003 (0.010) | −0.001 (0.014) | −0.052*** (0.015) |

| Age | 0.002 (0.003) | −0.007 (0.008) | 0.007** (0.004) | 0.003** (0.001) | −0.006*** (0.001) | −0.018*** (0.002) |

| Age squared | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000** (0.000) | 0.000*** (0.000) | 0.000*** (0.000) |

| High school graduate | −0.107* (0.059) | −0.264** (0.127) | −0.063 (0.050) | −0.025* (0.014) | 0.038*** (0.012) | 0.028 (0.023) |

| Some college | −0.190*** (0.046) | −0.452*** (0.116) | −0.120*** (0.038) | −0.029** (0.012) | 0.064*** (0.014) | 0.059*** (0.022) |

| Associate's degree | −0.213*** (0.061) | −0.448*** (0.121) | −0.154*** (0.055) | −0.029** (0.014) | 0.091*** (0.015) | 0.086*** (0.026) |

| Bachelor's degree and above | −0.201*** (0.057) | −0.532*** (0.128) | −0.140*** (0.043) | −0.036** (0.015) | 0.130*** (0.012) | 0.190*** (0.020) |

| Fair or poor general health status | −0.111*** (0.018) | −0.148*** (0.043) | −0.133*** (0.024) | 0.005 (0.006) | −0.160*** (0.012) | −0.209*** (0.008) |

| Own home | −0.016 (0.024) | −0.06 (0.040) | 0.018 (0.027) | −0.019** (0.009) | 0.063*** (0.006) | 0.080*** (0.012) |

| State-level movement trends (relative to Jan. 3 to Feb. 6, 2020) | ||||||

| Retail and recreation | −0.009 (0.007) | −0.009 (0.013) | −0.004 (0.008) | −0.002 (0.002) | −0.000 (0.002) | −0.006** (0.002) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | −0.003 (0.006) | 0.019 (0.015) | −0.01 (0.008) | 0.000 (0.002) | 0.000 (0.002) | 0.002 (0.002) |

| Parks | −0.000 (0.001) | −0.002* (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.000* (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) |

| Transit stations | 0.001 (0.005) | 0.002 (0.008) | −0.003 (0.006) | −0.005** (0.002) | 0.000 (0.001) | 0.005*** (0.002) |

| Workplaces | 0.007 (0.010) | 0.001 (0.023) | 0.024 (0.015) | 0.009** (0.004) | −0.002 (0.003) | 0.001 (0.004) |

| Residential | −0.008 (0.016) | −0.021 (0.039) | 0.013 (0.016) | −0.001 (0.005) | 0.006 (0.004) | 0.001 (0.005) |

| R-squared | 0.131 | 0.099 | 0.103 | 0.054 | 0.102 | 0.131 |

| N | 88,918 | 89,464 | 90,102 | 91,589 | 91,532 | 91,605 |

- Note: Each regression is weighted by the Household Pulse Survey household-level sampling weight. Standard errors clustered at the state of residence level are in parentheses. Other controls included but not shown: dummies for survey week and dummies for state of residence.

- Abbreviations: AS, arsinh or inverse hyperbolic sine; FAFH, food away from home; FAH, food at home.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we leverage a new experimental data product from the U.S. Census Bureau to investigate the link between unemployment and food spending/adequacy during the coronavirus pandemic (April 23 to June 23). We find that unemployment due to coronavirus-induced firm closures significantly reduced food spending, both on FAH and FAFH. Although unemployment due to a firm closure significantly increased households' likelihood of free food receipt, it was clearly not enough to offset the reduction in households' food spending. Indeed, compared with households containing employed persons, we find that households containing respondents who are unemployed due to a firm closure are significantly less likely to report having had a sufficient amount of food in the household in the past seven days and are also significantly less likely to report being at least moderately confident to be able to afford the kinds of food their households will need in the next four weeks. Given evidence that food donations improve food security (Mousa & Freeland-Graves, 2019), these results point to the potential role of USDA food assistance programs in providing food assistance for low-income households, inclusive of those households that may need temporary assistance following firm closures. Prior work has shown how economic activity affects the spread of viruses, which are clearly a major threat to human health (Adda, 2016). This study complements that literature by showing that involuntary workforce displacements during a pandemic can also have important adverse health consequences.

Unlike selective layoffs, which can be a function of worker productivity and other unobserved characteristics that may be related to health behavior (e.g., risk preferences), unemployment caused by firm closures is uncorrelated with a worker's productivity. Our analysis comparing employed persons to individuals who reported being unemployed in the past seven days because of a firm closure, conditional on our observables, may thus be interpreted as producing causal estimates of the impact of unemployment on important dietary outcomes. As a consequence, our study throws light on the usefulness of income support programs, especially during a major pandemic that results in major disruptions in business operations. As the US and other nations grapple with the many social and economic effects of COVID-19, our study suggests that food assistance or more general income support programs that target households with unemployed persons may help to soften the negative dietary impacts of job and income losses.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. The findings and conclusions in this publication are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy. The authors would like to thank Craig Gundersen and Matthias Rieger for very helpful comments and suggestions.

Endnotes

Appendix

| AS(Total food spending) | AS(Total FAFH spending) | AS(Total FAH spending) | Received free food | Enough food | Confident in future ability to afford food | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployed due to firm Closure | −0.164*** (0.026) | −0.598*** (0.049) | −0.089*** (0.029) | 0.025*** (0.005) | −0.087*** (0.009) | −0.153*** (0.008) |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| q-value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Effect size relative to sample mean | −15.1% | −45.0% | −8.5% | 35.7% | −9.5% | −21.0% |

| Individual characteristics | ||||||

| Log(number of kids) | 0.256*** (0.009) | 0.159*** (0.014) | 0.309*** (0.010) | 0.061*** (0.003) | −0.020*** (0.003) | −0.043*** (0.004) |

| Log(number of adults) | 0.437*** (0.018) | 0.480*** (0.031) | 0.498*** (0.015) | 0.027*** (0.004) | −0.022*** (0.003) | −0.059*** (0.005) |

| Married | 0.074*** (0.012) | 0.02 (0.021) | 0.104*** (0.015) | −0.004 (0.003) | 0.015*** (0.003) | 0.010** (0.004) |

| Male | 0.059*** −0.009 |

0.152*** −0.021 |

0.026*** −0.010 |

−0.014*** −0.003 |

0.004 −0.003 |

0.023*** −0.003 |

| Hispanic | 0.209*** (0.021) | 0.445*** (0.031) | 0.174*** (0.023) | 0.033*** (0.003) | −0.005 (0.006) | −0.073*** (0.008) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.160*** (0.026) | 0.423*** (0.053) | 0.081*** (0.029) | 0.017*** (0.006) | −0.057*** (0.005) | −0.125*** (0.009) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian/other | 0.048*** (0.015) | 0.059* (0.035) | 0.010 (0.021) | 0.004 (0.005) | −0.005 (0.005) | −0.048*** (0.009) |

| Age | 0.007*** (0.002) | 0.003 (0.004) | 0.010*** (0.003) | 0.001* (0.001) | −0.002*** (0.001) | −0.014*** (0.001) |

| Age squared | −0.000*** (0.000) | −0.000*** (0.000) | −0.000*** (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) | 0.000*** (0.000) | 0.000*** (0.000) |

| High school graduate | −0.104** (0.047) | −0.203* (0.107) | −0.056 (0.035) | −0.030*** (0.009) | 0.055*** (0.013) | 0.066*** (0.016) |

| Some college | −0.165*** (0.047) | −0.335*** (0.109) | −0.107*** (0.034) | −0.034*** (0.009) | 0.075*** (0.013) | 0.093*** (0.017) |

| Associate's degree | −0.182*** (0.043) | −0.338*** (0.103) | −0.136*** (0.035) | −0.035*** (0.009) | 0.087*** (0.013) | 0.112*** (0.017) |

| Bachelor's degree and above | −0.200*** (0.045) | −0.474*** (0.103) | −0.143*** (0.032) | −0.037*** (0.009) | 0.104*** (0.013) | 0.184*** (0.015) |

| Household income $50,000 to $74,999 | 0.142*** (0.024) | 0.240*** (0.038) | 0.123*** (0.025) | −0.034*** (0.004) | 0.061*** (0.005) | 0.114*** (0.008) |

| Household income $75,000 to $99,999 | 0.217*** (0.021) | 0.413*** (0.044) | 0.169*** (0.025) | −0.046*** (0.004) | 0.081*** (0.004) | 0.172*** (0.007) |

| Household income $100,000 to $149,999 | 0.301*** (0.024) | 0.484*** (0.047) | 0.266*** (0.030) | −0.058*** (0.004) | 0.083*** (0.004) | 0.216*** (0.006) |

| Household income $150,000 and above | 0.460*** (0.027) | 0.754*** (0.072) | 0.403*** (0.026) | −0.080*** (0.004) | 0.077*** (0.004) | 0.261*** (0.006) |

| Fair or poor general health status | −0.088*** (0.013) | −0.148*** (0.023) | −0.106*** (0.018) | 0.010** (0.004) | −0.126*** (0.008) | −0.199*** (0.005) |

| Own home | −0.028** (0.012) | −0.079*** (0.022) | −0.001 (0.017) | −0.013*** (0.004) | 0.040*** (0.004) | 0.057*** (0.006) |

| State-level movement trends (relative to Jan. 3 to Feb. 6, 2020) | ||||||

| Retail and recreation | −0.000 (0.003) | 0.013* (0.007) | −0.005 (0.004) | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.001 (0.001) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | −0.007 (0.005) | −0.004 (0.010) | −0.006 (0.005) | 0.0000 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) |

| Parks | 0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.001) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000* (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Transit stations | 0.001 (0.003) | 0.003 (0.007) | −0.002 (0.004) | −0.000 (0.001) | 0.001* (0.001) | 0.002 (0.001) |

| Workplaces | 0.005 (0.006) | −0.021 (0.019) | 0.018* (0.010) | 0.004 (0.002) | −0.001 (0.002) | −0.003 (0.003) |

| Residential | −0.000 (0.011) | −0.002 (0.022) | −0.002 (0.011) | 0.002 (0.002) | 0.004** (0.002) | 0.002 (0.003) |

| R-squared | 0.139 | 0.076 | 0.107 | 0.064 | 0.139 | 0.225 |

| N | 377,264 | 378,977 | 380,408 | 385,936 | 385,911 | 386,064 |

- Note: Each regression is weighted by the Household Pulse Survey household-level sampling weight. Standard errors clustered at the state of residence level are in parentheses. Other controls included but not shown: dummies for survey week and dummies for state of residence.

- Abbreviations: AS, arsinh or inverse hyperbolic sine; FAFH, food away from home; FAH, food at home.

| AS(Total food spending) | AS(Total FAFH spending) | AS(Total FAH spending) | Received free food | Enough food | Confident in future ability to afford food | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployed due to firm closure | −0.164*** (0.026) | −0.599*** (0.049) | −0.090*** (0.029) | 0.025*** (0.005) | −0.087*** (0.009) | −0.153*** (0.008) |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| q-value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Effect size relative to sample mean | −15.1% | −45.1% | −8.6% | 35.7% | −9.5% | −21.0% |

| Individual characteristics | ||||||

| Log(number of kids) | 0.256*** (0.009) | 0.159*** (0.014) | 0.309*** (0.010) | 0.061*** (0.003) | −0.020*** (0.003) | −0.043*** (0.004) |

| Log(number of adults) | 0.437*** (0.018) | 0.479*** (0.031) | 0.498*** (0.015) | 0.027*** (0.004) | −0.022*** (0.003) | −0.059*** (0.005) |

| Married | 0.074*** (0.012) | 0.021 (0.022) | 0.103*** (0.015) | −0.004 (0.003) | 0.015*** (0.003) | 0.010** (0.004) |

| Male | 0.059*** (0.009) | 0.151*** (0.021) | 0.026*** (0.010) | −0.014*** (0.003) | 0.004 (0.003) | 0.023*** (0.003) |

| Hispanic | 0.210*** (0.021) | 0.445*** (0.031) | 0.174*** (0.023) | 0.033*** (0.003) | −0.005 (0.006) | −0.073*** (0.008) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.160*** (0.026) | 0.423*** (0.053) | 0.081*** (0.029) | 0.017*** (0.006) | −0.057*** (0.005) | −0.125*** (0.009) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian/other | 0.048*** (0.015) | 0.059* (0.035) | 0.01 (0.021) | 0.004 (0.005) | −0.005 (0.005) | −0.048*** (0.009) |

| Age | 0.007*** (0.002) | 0.002 (0.004) | 0.010*** (0.003) | 0.001* (0.001) | −0.002*** (0.001) | −0.014*** (0.001) |

| Age squared | −0.000*** (0.000) | −0.000*** (0.000) | −0.000*** (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) | 0.000*** (0.000) | 0.000*** (0.000) |

| High school graduate | −0.104** (0.047) | −0.204* (0.106) | −0.056 (0.035) | −0.031*** (0.009) | 0.055*** (0.013) | 0.066*** (0.016) |

| Some college | −0.165*** (0.047) | −0.336*** (0.109) | −0.107*** (0.034) | −0.035*** (0.009) | 0.075*** (0.013) | 0.093*** (0.017) |

| Associate's degree | −0.182*** (0.042) | −0.339*** (0.103) | −0.136*** (0.035) | −0.036*** (0.009) | 0.087*** (0.013) | 0.112*** (0.017) |

| Bachelor's degree and above | −0.200*** (0.045) | −0.475*** (0.102) | −0.142*** (0.032) | −0.038*** (0.009) | 0.104*** (0.013) | 0.184*** (0.015) |

| Household income $50,000 to $74,999 | 0.141*** (0.024) | 0.241*** (0.038) | 0.123*** (0.025) | −0.034*** (0.004) | 0.061*** (0.005) | 0.114*** (0.008) |

| Household income $75,000 to $99,999 | 0.217*** (0.021) | 0.414*** (0.044) | 0.169*** (0.025) | −0.046*** (0.004) | 0.081*** (0.004) | 0.171*** (0.007) |

| Household income $100,000 to $149,999 | 0.302*** (0.024) | 0.484*** (0.047) | 0.266*** (0.030) | −0.058*** (0.004) | 0.083*** (0.004) | 0.216*** (0.006) |

| Household income $150,000 and above | 0.460*** (0.027) | 0.755*** (0.072) | 0.403*** (0.026) | −0.080*** (0.004) | 0.077*** (0.004) | 0.261*** (0.006) |

| Fair or poor general health status | −0.087*** (0.013) | −0.147*** (0.023) | −0.106*** (0.018) | 0.009** (0.004) | −0.126*** (0.008) | −0.199*** (0.005) |

| Own home | −0.028** (0.012) | −0.079*** (0.022) | −0.002 (0.017) | −0.013*** (0.004) | 0.040*** (0.004) | 0.057*** (0.006) |

| State-level movement trends (relative to Jan. 3 to Feb. 6, 2020) | ||||||

| Retail and recreation | −0.005 (0.005) | 0.006 (0.012) | −0.009 (0.006) | −0.002* (0.001) | −0.002 (0.002) | −0.001 (0.002) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | −0.002 (0.006) | 0.008 (0.012) | −0.002 (0.007) | −0.000 (0.001) | −0.000 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.002) |

| Parks | 0.000 (0.000) | −0.001 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.000** (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) |

| Transit stations | 0.003 (0.006) | 0.006 (0.010) | −0.001 (0.006) | −0.001 (0.001) | 0.003*** (0.001) | 0.001 (0.002) |

| Workplaces | 0.004 (0.005) | −0.046 (0.027) | 0.019 (0.012) | 0.006** (0.003) | 0.001 (0.002) | −0.001 (0.004) |

| Residential | 0.004 (0.012) | 0.001 (0.023) | 0.005 (0.012) | −0.000 (0.002) | 0.002 (0.002) | −0.001 (0.004) |

| R-squared | 0.140 | 0.076 | 0.107 | 0.065 | 0.139 | 0.225 |

| N | 377,264 | 378,977 | 380,408 | 385,936 | 385,911 | 386,064 |

- Note: Each regression is weighted by the Household Pulse Survey household-level sampling weight. Standard errors clustered at the state of residence level are in parentheses. Other controls included but not shown: dummies for survey week and dummies for state of residence.

- Abbreviations: AS, arsinh or inverse hyperbolic sine; FAFH, food away from home; FAH, food at home.