Experience Academic Wellbeing Index as Predictor of Psychological Wellbeing and Flourishing

Abstract

Background: The correlation between academic performance and educational support environments is crucial for student wellbeing, as highlighted by recent educational reports.

Aims: This study introduces and validates the Experience of Academic Wellbeing Index (EAWI), designed to assess three dimensions of academic experience: presage (personal and contextual regulation), process (regulation in the teaching–learning process) and product (physical and psychological health). Additionally, the predictive relationship with psychological wellbeing and flourishing was tested.

Sample: The sample consisted of 565 university students aged 18–25 from various disciplines, providing a broad base for analysis.

Methods: Employing an ex post facto design, participants completed three validated instruments over 3 months and two inventories on psychological wellbeing and flourishing at the end. Structural validity, reliability and predictive analyses (ANOVA and MANOVA) were conducted.

Results: The EAWI proved to be a reliable psychoeducational construct, significantly predicting psychological wellbeing and flourishing amongst students. It effectively measured the intended variables, confirming its structural validity.

Conclusions: The EAWI is applicable in university settings for assessing and enhancing student academic wellbeing. Its effectiveness in diverse educational contexts warrants further investigation.

1. Introduction

Recent data confirms that issues around the wellbeing and mental health of students in preuniversity and university formal educational contexts are a well-founded concern [1–4]. The PISA 2022 report [5] confirmed that the best academic performance is seen in settings whose ethos is characterised by a sense of belonging, life satisfaction, teacher support for learning and engagement and support for the individual from teachers when needed.

Prior research has shown that educational environments may present factors that promote academic wellbeing or, conversely, academic unwellness. Academic wellbeing has been defined as a subjective feeling of satisfaction that is correlated with physical, mental and social wellbeing in a school or academic environment [6, 7]. Conversely, academic unwellness has been defined as an overall subjective feeling of negative experience which is correlated with physical, mental and social ill-health or unease [8].

It has been determined that better performance and greater learning competence are associated with different factors, inherent of both context [9] and the personal characteristics of individual students [10]. Those things lead to a positive subjective perception of school and university experience, positive academic emotions (satisfaction and pride) and a greater degree of emotional wellbeing [11–14]. Recent works have modelled that relationship and demonstrated protective and risk factors in university contexts [15].

The Conceptual Utility Model for the Management of Stress and Psychological Wellbeing, CUMSPW [16] provides a predictive model to analyse factors in relation to mental wellbeing in different environments. The model has enabled the selection of the—protective and risk—factors empirically analysed here in function of the level of each in the context of the psychology of education, following a clear line from earlier research.

Based on Bigg’s [17] model, the utility model assumes that it is possible to posit three types of factors (presage-process-product) that may operate as protective versus risk factors in the educational process and so may in turn impact the health and academic wellbeing of students. In this instance, an abbreviated version of the factors that can be analysed was used, based on prior findings as to their significance:

1.1. Educational Presage Factors: Personal and Contextual Regulation

The presage and predictive factors analysed relate to personal and contextual factors taken from self- versus external regulation behaviour theory [18–21] which may operate to predict a condition of wellbeing or unwellness and, as such, may be protective or risk factors.

1.1.1. Personal Educational Presage Factors

It has been found that the behavioural personal characteristics of students can exhibit three levels of self-regulatory behaviour [22]. Students who self-regulate and have a high level of conscientiousness, described as behavioural self-regulation (SR); students who do not self-regulate, whether due to regulatory fatigue or because they have developed insufficient self-regulatory behaviour, described as behavioural nonregulation (NR) or deregulation; those whose behaviour is dysregulatory or dysfunctional, with resulting behavioural excesses and deficits, are described as exhibiting behavioural dysregulation (DR). Prior research has shown the consistency of these levels [23–27].

1.1.2. Contextual Educational Presage Factors

Educational context has been shown to be a key element in terms of optimising or hindering personal development and the learning process itself [28]. A regulatory educational context (REC) has been described as a context that has been appropriately configured so as to be propitious to an optimal, integrated process of personal development and learning by individuals to self-regulate and be independent. Conversely, a nonregulatory or deregulatory context (NRC) is one that does not operate as an adequate ‘scaffold’ or assistance to the individual in their development. Finally, a dysregulatory context (DRC) is one that promotes behavioural maladjustment and dysfunction as a result of its structure and background and as a result of behaviours in the context [23, 29, 30].

1.2. Process or Mediating Educational Factors in Academic Wellbeing: Regulation in the Course of the Teaching–Learning Process

1.2.1. Personal Factors Proper to the Student Who Is Learning

An adequate level of self-regulated learning (SRL) and an effective strategy combine to form a protective factor. Much recent prior research has shown that students who have a good level of SR and strategic learning in specific learning processes have a greater level of satisfaction, positive emotion and wellbeing [31]. Consequently, the level of metaskill in, or competence for, learning can be considered a protective factor against stress and a promoter of academic wellbeing [32]. Conversely, the lack of such metaskill or competence is a risk factor for poor academic wellbeing [33, 34].

1.2.2. Educational Teaching Factors

Regulatory teaching (RT) has also been shown to be a protective factor or a factor that promotes wellbeing. It has been established that effective teaching is itself a promoter of positive emotionality and a subjective experience of satisfaction [35–37]. Conversely, nonregulatory or dysregulatory teaching promotes a subjective experience of dissatisfaction and subjective negative emotionality [38, 39].

1.3. Educational Product Variables Inherent to Academic Wellbeing: Academic Health

Academic health can be defined in line with the suggestion of the World Health Organisation [40] not just as an absence of illness, but as a state of social, mental and physical wellbeing in academic settings. From a contemporary perspective, it entails a state of biopsychosocial wellbeing [41]. Prior research has shown that academic (physical and mental) health is predictive of a state of flourishing [42]. There is also evidence of a significant association between stress and levels of depression and anxiety in students [43].

The Experience of Academic Wellbeing Index (EAWI) is an averaged multidimensional tool that combines the personal and contextual parameters postulated earlier in the Conceptual Model of Management of Stress and Psychological (CMMSPW) [44], in an adapted, abbreviated format. Prior research has defined those parameters with their corresponding weights in each of the factors that it comprises as propitious to a subjective experience of satisfaction and personal growth during a teaching–learning process [45]. The factors that it comprises are as follows:

Average score for SR behaviour in educational settings (SR). This is a score for personal SR which presents different average levels of personal regulation: (1) low, dysregulatory behaviour; (2) moderate, nonregulatory behaviour and (3) high, regulatory behaviour. This construct is based on the theory of internal-external regulation and has been supported by copious evidence [18–21].

Average score for contextual regulation behaviour in educational settings (CR). This is a score for contextual regulation which presents different average levels of contextual regulation: (1) low, DRC; (2) moderate, NRC; (3) and high, regulatory context. This construct is based on the theory of internal-external regulation [18–21], and its discriminative power has been supported by considerable evidence.

1.3.1. Average Score for SRL

This is the level of strategic SRL, which presents different average levels: (1) low, dysregulatory learning; (2) moderate, nonregulatory or deregulatory learning and (3) high, SRL. Extensive evidence has also been collected in relation learning and coping strategies, positive emotionality and achievement [19–21].

1.3.2. Average Score for RT

This is the level of RT, which presents different average levels: (1) low, dysregulatory teaching; (2) moderate, nonregulatory or deregulatory teaching and (3) high, external RT. Considerable evidence has been gathered of its role in levels of stress, learning focuses, emotional levels and stress in students, including during the pandemic, as a mitigating factor [19–21, 45].

1.3.3. Average Score for Physical and Psychological Health

Academic health is a combined construct based on information about physical and mental health of students in a given teaching–learning environment [42]. Both factors can be seen as indicators of physical and mental wellbeing in the model based on this research.

Psychological wellbeing integrates the biopsychosocial model [40] through two paradigms: hedonic, focusing on life satisfaction and happiness [46], and eudaimonic, emphasising human potential and the importance of overcoming challenges for wellbeing. It highlights life purpose, mastery, positive relationships, self-acceptance, growth and autonomy [47–49]. Recent perspectives merge these views, defining flourishing as a state of wellbeing and effective functioning, encapsulating hedonic and eudaimonic elements like competence, emotional stability, meaning, optimism and positive relationships, marking a comprehensive measure of mental wellbeing [50, 51].

Academic wellbeing has been assessed from many perspectives. Thus, some methods of measuring student or academic wellbeing focus on assessing a student’s degree of satisfaction with their educational environment. Like others, Loderer et al. [52], for example, developed a self-completed unidimensional scale that assesses academic wellbeing on the basis of overall judgements from students as to their wellbeing in the learning environment. In a similar fashion, Stockinger et al. [53] developed an academic wellbeing scale on the basis of the Multidimensional Student Life Satisfaction Scale by Huebner [54], comprising six items that measure the psychological wellbeing of students associated with their academic experience. The scales referenced assess wellbeing in terms of overall psychological and emotional wellbeing in educational contexts.

Borgonovi and Pál [55], on the other hand, validated an academic wellbeing scale that contains 58 items that assess different dimensions of student wellbeing including cognitive skills, motivation, psychological aspects, physical health, relationships with others, material wellbeing and quality of teaching. This scale is based on the five traditional dimensions of academic wellbeing: cognitive, psychological, social, physical and material wellbeing. Similarly, Hascher [56] published the Student Wellbeing Questionnaire (SWBQ) which has six factors: positive attitudes towards school, enjoyment of school, positive academic self-concept, concerns about school, physical issues at school and social problems at school. However, these measurement instruments fail to take account of the interaction or combination of the individual’s characteristics and those of their context. Examples include the pre-existing social and personal factors that a student brings to their educational setting and aspects of the teaching–learning process that may directly impact a student’s academic wellbeing.

The EAWI presented in this article, unlike scales based on classical models focused on personal characteristics that affect psychological wellbeing, takes account of metacognitive variables associated with self-regulated conduct in learning and contextual regulation of learning and also includes regulation of learning by educators and a student’s self-regulation in class, as well as academic health, both physical and mental. Consequently, it provides more complete and enriching information about both personal and environmental factors that may act as protective or risk factors for a student’s academic wellbeing. This opens up the opportunity to develop interventions more precisely aimed at improving academic wellbeing, focused on the teaching–learning process, something that other scales do not offer.

Considering the issues discussed above, the objective of this research was to empirically test the validity and reliability of academic or educational wellbeing as a multidimensional subjective construct of experience of teaching–learning in a given educational or academic setting. The study hypotheses were as follows: (1) The three measurements of general personal and contextual regulatory (presage) factors, specific (process) factors of regulation of the teaching–learning process and the state of the mental and physical health (product factors) will be positively correlated and will saturate in a significant multidimensional structural construct and that those measurements will have appropriate levels of reliability. (2) The factors comprising the index will show sufficient, significant predictive power in relation to psychological wellbeing and flourishing, and that the differential levels (high-moderate-low) of academic wellbeing will significantly determine levels of mental wellbeing and flourishing, which are taken as criteria of external validity.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The sample was made up of a total of 672 students at two universities in Spain, aged 18–25. Of the sample, 85.5% were women, and 14.5% were men. The mean age was 21.33 years. The students were evenly split between the two universities. The sample was a convenience sample of students taking academic courses at different levels. Only students whose completed sociodemographic details showed no clinical diagnosis (ADHD, depression, anxiety, personality disorder, etc.) were selected. Students who did not complete the full suite of inventories (presage-process-product and external validity) were removed from the sample.

2.2. Instruments

The Self- versus External-Regulation Scale (SRL-ERL) [19–21]. This scale evaluates self and external regulation behaviours in learning through six subscales, each featuring six items that assess internal behavioural regulation and the influence of the educational context. These items categorise responses as regulatory, nonregulatory or dysregulatory. For instance, internal regulatory behaviours are assessed by items like ‘I observe and monitor myself to check whether I am managing,’ whilst external dysregulatory influences are measured by items such as ‘The context of my life (family, environment, friends) encourages me to focus my attention on taking decisions to enjoy the moment and to delay decisions that are important for me.’ The scale’s structural validity and reliability are confirmed with robust metrics (chi − square = 2066.344, p < 0.52, df = 579; chi/df = 3.569; RMR = 0.0231; NFI = 0.902, RFI = 0.917; IFI: 0.928; TLI = 0.916; CFI = 0.927; RMSEA = 0.035; Hoelter = 633, 658) and overall reliability (alpha = 0.730; Spearman-Brown 0.786). Subscale reliability coefficients range from 0.759 to 0.915, demonstrating consistent internal consistency and reliability in measuring the intended constructs.

2.2.1. Interactive Assessment of the Teaching–Learning Process (ATLP)

The scales for ATLP, student version [57], were used to evaluate the perception of regulation in the teaching–learning process in students. The scale entitled RT is Dimension 1 of the confirmatory model. IATLP-D1 comprises five factors: specific RT, regulatory assessment, preparation for learning, satisfaction with the teaching and general RT; Dimension 2 which measures perception of SR of learning (32 items), based on the following six factors: satisfaction with the learning process, learning and self-regulation strategies, SRL behaviour at university, motivation to learn, self-evaluation and planning of learning and learning strategies. The scale showed a factor structure with adequate fit indices (chi − square = 590.626; df = 48, p < 0.36; CF1 = 0.958, TLI = 0.959, NFI = 0.950, NNFI = 0.967; RMSEA = 0.068) and adequate internal consistency (IATLP D1: α = 0.830; specific RT, α = 0.897; regulatory assessment, α = 0.883; preparation for learning, α = 0.849; satisfaction with the teaching, α = 0.883 and general RT, α = 0.883).

Entwistle Teaching–Learning Questionnaire (ETLQ) [58]. This inventory measures the degree of satisfaction with the experience of formal teaching–learning at university [59]. It has three dimensions: D1, teaching and learning experiences (F1. F9)/9 (items: 1–44); D2, perceived easiness of demands made (F10. F14)/5 (items: 45–54) and D3, knowledge and learning acquired (F15)/1 (items: 55–62). Confirmatory factor analysis showed an adequate factorial structure (chi − square = 178.53; p < 0.24; CFI = 0.93, GFI = 0.94 and RMSEA = 0.03) [60] and appropriate reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.854; omega = 0.832). This construct was used as correlate for the external validity of the EIPEA scale. There were significant, moderate correlations between the factors on the two scales, which shows their factor independence (see Table 1).

| D1.RT | D2.SRSL | ATLP.Tot | |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1.ETLQ | 0.712 ∗∗ | 0.610 ∗∗ | 0.712 ∗∗ |

| D2.ETLQ | 0.300 ∗∗ | 0.308 ∗∗ | 0.395 ∗∗ |

| D3.ETLQ | 0.410 ∗∗ | 0.546 ∗∗ | 0.511 ∗∗ |

| TOT.ETLQ | 0.605 ∗∗ | 0.618 ∗∗ | 0.691 ∗∗ |

- Note: D1.ETLQ, teaching and learning experiences (F1–F9)/9 (items: 1–44); D2.ETLQ, perceived easiness of demands made (F10–F14)/5 (items: 45–54); D3.ETLQ, knowledge and learning acquired (F15)/1 (items: 55–62); D1.RT, regulatory teaching; D2.SRSL, self-regulated and strategic learning; ATLP.Tot, total of regulatory teaching and self-regulated learning. ∗∗p < 0.01.

2.2.2. Student Health Behaviour

This variable was measured using the Physical and Psychosocial Health Inventory [42]. The WHO defines health as a comprehensive state of physical, mental and social wellbeing, beyond just the absence of disease or infirmity. The questions in the inventory focus on the effects of study, for example, ‘I feel anxious about my studies.’ Students responded on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Taken as a whole, the items provide a general assessment of the subjects’ general health, incorporating aspects such as eating, sleep and recreational habits, and the possible anxiety, depression or stress caused by studying. In the Spanish sample, the model obtained good fit indices (X2 = 109,713; DF = 19, CMIN/DF = 5774; p < 0.09; CFI = 0.951, RFI = 0.908, GFI = 0.959, IFI = 923; TLI = 0.959; RMSEA = 0.034), with a Cronbach alpha = 0.779; omega = 0.781.

2.2.3. Psychological Wellbeing

The study employed the Spanish version of the Psychological Wellbeing Scale [61], which features 29 items across six dimensions as defined by Ryff and colleagues ([47–49]). These dimensions include self-acceptance (e.g. ‘Generally, I feel positive and confident about myself’), autonomy (e.g. ‘I tend to be influenced by people with strong opinions’), positive relationships (e.g. ‘I feel that my friendships contribute a lot to my life’), personal growth (e.g. ‘I feel that I have developed a lot as a person over time’), mastery of the environment (e.g. ‘Generally, I feel that I am in charge of my situation’) and purpose in life (e.g. ‘I have clear direction and purpose in my life’). The internal consistency of these scales was strong, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.70 to 0.85. Responses were rated on a 1–5 Likert scale, indicating higher scores reflect greater wellbeing. Confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated a good fit, with indices including χ2 = 35.0, p < 0.08, df = 24, χ2/df = 1.46, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.05 and SRMR = 0.06, validating the scale’s structure.

2.2.4. The Flourishing Scale

The study used a Spanish-language version that had been validated in Spanish-speaking populations of the Flourishing Scale [46, 62]. The scale measures flourishing or optimal experience and contains eight items. Responses are given on a 1–5 Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The individual items comprise statements such as ‘I have a useful, meaningful life’ or ‘I am a good person and I live a good life’. Cronbach’s alpha for the Spanish-speaking sample is 0.85, with omega at 0.81. Unidimensionality of the scale and measurement invariance in the samples were confirmed (chi − square = 79,392; degrees of freedom [44–24] = 20; p < 0.10; Ch/Df = 3970; SRMR = 0.052; NFI = 0.946; RFI = 0.953; IFI = 0.959; TLI = 0.955; CFI = 0.958; RMSEA = 0.039; HOELTER = 757 [p < 0.05] and 905 [p < 0.01]).

2.3. Procedure

The guidance services of both universities invited teaching stuff to participate, and they in turn invited their students to participate voluntarily and anonymously. Students gave informed consent and then voluntarily completed the questionnaires online: http://www.inetas.es [63]. Participants were asked to complete the inventories outside class time online once a month over the study period. Five different teaching–learning processes were assessed in the different courses over a period of 2 years. The presage variable (SRL-ERL) was measured in September to October 2021 and 2022. The process variable (teaching and learning process) was measured in February to March 2021 and 2022. Finally, the product variable (health academic, flourishing and wellbeing) was measured in May to June 2021 and 2022. The process was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of within the framework of a larger R&D Project (2018–2021; ref. PGC2018-094672-B-I00).

Study data were kept anonymously on a secure server. Access granted to the research team was restricted to anonymised responses. Numerical identifiers were used to link participants to their responses. The study was carried out in accordance with generally recognised ethical principles of psychology. Personal data was protected to the standard required by law. The data server was hosted by NETERRA DATACENTERS EUROPE1; data processing was carried out by Mapache Software Europe under appropriate data security protocols. The principal investigator acted as data controller.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Structural Confirmatory Analysis

Structural equational modelling (SEM) and a mediational model for complex measurement [64] were carried out. Goodness of fit was initially assessed by the chi-squared:degrees of freedom ratio, followed by CFI, NFI, RFI and TLI. All measurements of fit for the incremental model exceeded the threshold set of 0.90 [65]. CF was also adequate at 0.928. The results for the original scale were reproduced. RMSEA was 0.08 below the 0.09 threshold value [66]. RMSEA would optimally exceed 0.90. The Hoelter index was used to determine sample size adequacy. The software used for statistical analysis was AMOS V. 23.0 [67].

To test Hypothesis 1, normality was assessed, and bivariate Pearson correlation analysis and predictive analysis were performed. To test Hypothesis 2, ANOVA and MANOVA were carried out using SPSS V. 26.0 [68]. For the statistical analysis, the mean of scores for the variables in the Experience of Educational or Academic Wellbeing index (EEAWI) was used.

The average score for SR in educational settings was calculated using the formula [(SRL-NRL-DRL)/3] with scores in the range [+1.00 to −2.17]. Cluster analysis generated a numerical value of (1) low regulation or DR (−2.17 to −0.78), (2) moderate regulation or NR (−0.77 to −0.23) and (3) high regulation (−0.22 to 1.00), in function of the level achieved.

The average score for external or contextual educational settings was calculated using the formula [(ER-ENR-ED)/3] with scores in the range [+1.00, −2.11]. Cluster analysis generated a numerical value of (1) low external regulation or DR (−2.11 to −0.785), (2) moderate external regulation or NR (−0.784 to −0.06) and (3) high regulation external (−0.05 to 1.00), in function of the level achieved.

The average score for strategic or SRL was calculated as the average for the dimension (D2 = F4 + F8 + F3 + F5 + F7 + F6) with cluster analysis to stratify the following levels: (1) low (1.00 to 3.275), (2) moderate (3.276 to 4.02) and (3) high (4.03 to 5.00).

The average score for RT was calculated as the average score for this dimension (D1 = F1 + F2 + F0 + F10) and cluster analysis to stratify the following levels: (1) low level or dysregulatory teaching (1.00 to 3.08), (2) moderate level or nonregulated learning (3.09 to 3.98) and (3) high level or RT (3.99 to 5.00).

The average score for physical health was determined by cluster analysis to stratify (1) low level of physical health (1.00 to 2.93), (2) moderate level of physical health (2.94 to 3.95) and (3) high level of physical health (3.96 to 5.00).

The average score for mental wellbeing was determined by cluster analysis to stratify (1) low level of mental wellbeing (1.00 to 2.32), (2) moderate level of mental wellbeing (2.33 to 3.67) and (3) high level of mental wellbeing (3.68 to 5.00).

The average combined score for the scores set out above allows us to locate a student using the index of experience of factors of academic wellbeing, which itself requires the average score for protective-risk factors [16]:

Low index (1) = low protection and high risk (1.00 to 0.79).

Moderate index (2) = moderate protection and moderate risk (1.80 to 2.42).

High index (3) = high protection and low risk (2.43 to 3.00).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results

The descriptive results showed relative fit to normality parameters in the different factors analysed (see Table 2).

| Mean | SD | Asymmetry | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRLE | −0.36 | 0.61 | −0.06 | −0.617 |

| REC | −0.34 | 0.72 | 0.143 | −0.897 |

| RT | 3.63 | 0.71 | −0.379 | 0.053 |

| SRL | 3.38 | 0.75 | −0.26 | 0.008 |

| PHYSHEALTH | 3.83 | 0.76 | −0.657 | 0.358 |

| PSYCHEALTH | 2.91 | 0.95 | −0.026 | −0.435 |

| WBTOT | 4.43 | 0.67 | −0.313 | −0.378 |

| FLTOT | 4.12 | 0.65 | −0.811 | 0.63 |

- Abbreviations: FLTOT, flourishing total; PHYSHEALTH, physic health; PSYCHEALTH, psychological health; REC, regulatory educational context; regulated, learning; regulation, behaviour in educational situations; RT, regulatory teaching; SRL, self; SRLE, self; WBTOT, psychological wellbeing total.

3.2. Linear Associations and Predictions

3.2.1. Association Results

Correlation analysis showed significant moderate correlations but without loss of factorial independence. It is noteworthy that there was a significant positive relationship amongst all the factors of varying strength. The dimension of personal regulation or SR in learning contexts (SRL) showed a significant positive correlation with all dimensions. Its correlation was particularly strong with SRL and mental health. This shows that general nonregulatory behaviour makes more likely poorer regulation in specific learning and a lower level of mental wellbeing and flourishing. The dimension of contextual regulation or REC showed a positive correlation with RT, with physical and mental health and with wellbeing and flourishing. In other words, nonregulatory and dysregulatory educational contexts entail lower levels of mental wellbeing and flourishing (see Table 3).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SR | ||||||

| 2. ER | 0.639 ∗∗ | |||||

| 3. SRL | 0.338 ∗∗ | 0.197 ∗∗ | ||||

| 4. RT | 0.268 ∗∗ | 0.237 ∗∗ | 0.565 ∗∗ | |||

| 5. PHYSHEALTH | 0.192 ∗∗ | 0.191 ∗∗ | 0.205 ∗∗ | 0.352 ∗∗ | ||

| 6. PSYCHEALTH | 0.268 ∗∗ | 0.212 ∗∗ | 0.145 ∗∗ | 0.116 ∗∗ | 0.144 ∗∗ | |

| 7. INDEX | 0.285 ∗∗ | 0.240 ∗∗ | 0.227 ∗∗ | 0.297 ∗∗ | 0.690 ∗∗ | 0.716 ∗∗ |

- Abbreviations: ER, regulatory educational context; INDEX, EAWI; PHYSHEALTH, physic health; PSYCHHEAL, psychological health; regulated, and strategic learning; regulation, in educational situations; RT, regulatory teaching; SR, personal self; SRL, self.

- ∗∗p < 0.001.

3.2.2. Predictive Results

Linear prediction analysis complemented the relationship described above. The factors that comprise the construct educational or academic wellbeing predicted mental wellbeing to a degree that was significant (r2 = 0.425) (F(6, 306) = 36,687, p < 0.001). The most predictive factors were the level of SR in learning situations (B = 0.171; p < 0.01), a REC (B = 0.122; p < 0.05), the level of self-regulated specific learning (B = 0.232; p < 0.01), the level of RT (B = 0.540; p < 0.05), physical health (B = 0.242; p < 0.01) and psychological health (B = 0.205; p < 0.01).

In addition, the factors that comprise educational or academic wellbeing predicted flourishing to a degree that was significant (r2 = 0.432) (F(6, 253) = 33,101, p < 0.001). In this case, the most predictive factors were the level of specific self-regulated during learning (B = 0.175; p < 0.01), physical health (B = 0.493; p < 0.001) and mental health (B = 0.101; p < 0.05).

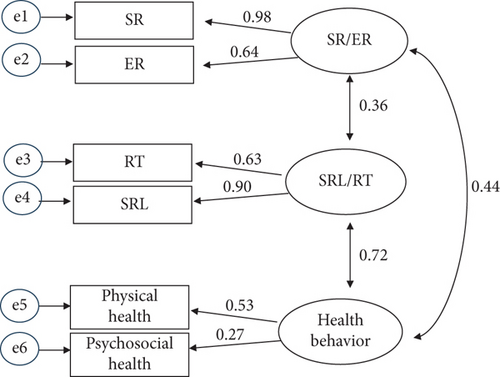

3.2.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Dimensions of the EAWI

The modelling tested showed adequate values (X2 [27–21] = 21,893, p < 0.52; CMIN/DF = 3649; NFI = 0.979; RFI = 0.926; IFI = 0.985; TLI = 0.945; CFI = 0.984; RMSEA = 0.035; Hoelter = 1237 [p < 0.01], 1651 [p < 0.01]). It shows that the experience of academic wellbeing is constituted by its three dimensions: (1) presage, conformed of the factors SR and REC; (2) process, conformed of the factors regulatory learning and strategic SRL and (3) product, conformed of the factors physical health and mental wellbeing (see Figure 1).

3.3. Effect of Level of Experience of Academic Wellbeing (Low-Moderate-High) on Mental Wellbeing and Flourishing

3.3.1. Adequacy of Groups

To establish the adequacy of the group, we took this factor as the independent variable (IV) (level of protective factors: low-moderate-high) and analysed its effects on the dependent variables (DVs) compromising the factors. We observed a significant principal effect of the IV on the six factors that comprise it (F[12, 608] = 34,801 (Pillai); p < 0.001; r2 = 0.407; power = 1.00). Levene’s test of equal error variance in all cases did not have sufficient level of significance (L[2, 308] < 2104, p > 0.05) (see Table 4).

| Groups of protective factors (IV) | Total average (n = 311) | Post | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Low (n = 77) | 2. Moderate (n = 134) | 3.High (n = 100) | |||

| Personal self-regulation | 1.36 (0.55) | 2.02 (0.72) | 2.71 (0.49) | 2.08 (0.80) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗ |

| Contextual regulation | 1.32 (0.57) | 1.90 (0.84) | 2.76 (0.51) | 2.03 (0.88) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗ |

| Self-regulated learning | 3.11 (0.58) | 3.71 (0.49) | 4.13 (0.42) | 3.70 (0.62) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗ |

| Regulatory teaching | 3.12 (0.71) | 3.66 (0.66) | 4.17 (0.50) | 3.69 (0.74) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗ |

| Physical health | 3.28 (0.73) | 3.71 (0.74) | 4.33 (0.44) | 3.81 (0.77) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗ |

| Psychology health | 2.22 (0.85) | 2.99 (0.85) | 3.62 (0.72) | 3.00 (0.96) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗ |

- ∗p < 0.05.

Partial effects showed a significant principal effect of the group of index factors (or protective factors) on each specific DV. The largest effects were for personal SR (F[2, 310] = 105,574, p < 0.001; r2 = 0.407; power = 1) and regulatory context (F[2, 310] = 98,306, p < 0.001; r2 = 0.390; power = 1). In every case, post analyses were 3 > 2 > 1 (p < 0.001), although the remaining variables were between r2 = 0.371 (SRL) and r2 = 0.271 (physical health).

3.3.2. Effect of the Level of the EAWI on Mental Wellbeing and Flourishing

There was a significant principal effect of the level of the Academic Wellbeing Index (low-moderate-high) on total mental wellbeing (F[2, 291] = 73,357; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.337; power = 1.00). Levene’s test of equality was not significant (L[2, 288] = 2346; p > 0.12). In addition, there was an observed secondary effect in its components (F[12, 568] = 12,163; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.204). Levene’s test of equality was not significant (L[2, 288] = 2346; p > 0.12). Partial effects showed greater power of the level of academic wellbeing in relation to self-acceptance (F[12, 568] = 63,841; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.307), to personal growth (F[12, 568] = 38,077; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.287) and to purpose (F[12, 568] = 34,379; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.193). In the case of flourishing, the trend was the same, with an apparent significant principal effect of educational or academic wellbeing on the level of flourishing (F[2, 291] = 35,075; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.218; power = 1.00). Direct values are shown in Table 5.

| DV | Levels of academic wellbeing experience index (IV) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Moderate | High | Total average | Post | |

| (n = 134) | (n = 254) | (n = 194) | (n = 582) | ||

| Wellbeing | 3.90 (0.61) | 4.42 (0.61) | 5.49 (0.45) | 4.49 (0.69) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| Self-acc. | 3.23 (0.97) | 3.99 (0.84) | 4.76 (0.63) | 4.09 (0.97) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| Relationships | 3.95 (0.88) | 4.29 (1.03) | 5.05 (0.74) | 4.46 (1.00) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| Autonomy | 3.88 (0.72) | 4.30 (0.69) | 4.81(0.77) | 4.37 (0.80) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| Environment | 3.84 (0.92) | 4.46 (0.89) | 4.81 (0.82) | 4.44 (0.94) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| Growth | 4.35 (0.93) | 4.94 (0.80) | 5.42 (0.58) | 4.97 (0.86) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| Purpose | 4.08 (0.75) | 4.56 (0.74) | 5.02 (0.66) | 4.60 (0.79) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| Flourishing | 3.70 (0.63) | 4.11 (0.60) | 4.49 (0.41) | 4.13 (0.63) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

- ∗∗p < 0.01.

3.3.3. Effect of the Level of Each Variable in the EAWI on the Level of Mental Wellbeing and of Flourishing

The MANOVA and ANOVA carried out showed significant principal effects in all cases, showing the effect of a low-moderate-high level of each of the variables considered that make up the index on mental wellbeing: SR (F[2, 278] = 33,294 (Pillai); p < 0.001; r2 = 0.193; power = 1.00), external regulation (F[2, 278] = 23,602 (Pillai); p < 0.001; r2 = 0.152; power = 1.00), SRL (F[2, 278] = 33,294 (Pillai); p < 0.001; r2 = 0.193; power = 1.00) and regulated teaching (F[2, 278] = 17,057 (Pillai); p < 0.001; r2 = 0.098; power = 1.00).

There were also similar effects for flourishing: self-regulation (F[2, 278] = 23,602 (Pillai); p < 0.001; r2 = 0.152; power = 1.00), external regulation (F[2, 278] = 18,099 (Pillai); p < 0.001; r2 = 0.121; power = 1.00), SRL (F[2, 278] = 16,377 (Pillai); p < 0.001; r2 = 0.105; power = 1.00) and regulated teaching (F[2, 278] = 11,790 (Pillai); p < 0.001; r2 = 0.070; power = 1.00). Levene’s test of error variance equality was not significant in any instance (see Table 6).

| IV level | 1. Low | 2. Moderate | 3. High | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 134) | (n = 254) | (n = 194) | (n = 582) | Post | |

| DV. Psychological wellbeing | |||||

| SR | 4.11 (0.64) | 4.42 (0.64) | 4.85 (0.57) | 4.49 (0.68) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| ER | 4.20 (0.68) | 4.31 (0.66) | 4.79 (0.61) | 4.46 (0.97) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| SR learning | 3.80 (0.64) | 4.48 (0.60) | 4.74 (0.57) | 4.47 (0.67) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| ER teaching | 4.15 (0.69) | 4.36 (0.66) | 4.71 (0.61) | 4.47 (0.67) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| Physical health | 3.84 (0.92) | 4.46 (0.89) | 4.81 (0.82) | 4.44 (0.94) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| Pshych. health | 3.92 (0.61) | 4.32 (0.69) | 4.77 (0.57) | 4.45 (0.67) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| DV. Flourishing | |||||

| Self-Reg. | 3.95 (0.70) | 4.01 (0.59) | 4.41 (0.51) | 4.14 (0.63) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| Ext. Reg. | 3.90 (0.59) | 3.98 (0.69) | 4.39 (0.49) | 4.12 (0.63) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| SR learning | 3.63 (0.63) | 4.11 (0.58) | 4.38 (0.55) | 4.13 (0.63) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| ER teaching | 3.39 (0.67) | 4.02 (0.60) | 4.33 (0.59) | 4.13 (0.63) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| Physical health | 3.72 (0.91) | 4.36 (0.86) | 4.78 (0.61) | 4.25 (0.83) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

| Psychol. health | 3.50 (0.93) | 4.05 (0.57) | 4.42 (0.46) | 4.12 (0.63) | 3 > 2 > 1 ∗∗ |

- ∗∗p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

- 1.

The three measurements constituting the construct will correlate and saturate in a significant single multidimensional structural construct showing adequate reliability values. This hypothesis has been confirmed with the appearance of both the expected significant values and appropriate structural values and individual reliability values. These results ratify prior results that have shown a significant positive association between personal-contextual regulation, a RT–learning process and levels of mental and physical health [69, 70]. They also provide further evidence that the factors comprising the EAWI work on the premise of the Matthew effect: in other words, ‘more to more’ and ‘less to less’ [71].

- 2.

The factors that comprise the index will show significant differential determinative predictive capacity in relation to mental wellbeing and flourishing. The hypothesis has been confirmed and the corresponding null hypothesis rejected because the level (low-moderate-high) of the EEAWI significantly determined the level of mental wellbeing and flourishing, which have been taken as external validity criteria. Prior research has generated partial results on the same lines [51].

The most obvious limitation is that the index has been calculated in university populations in Spain rather than in a wider population and diverse cultures. Consequently, it would be necessary to revalidate the calculations in other populations, different types of individuals of varied nationalities and cultures. Doing so will require the use of multicultural versions of the tests used. The e-coping with stress tool (http://www.inetas.net) is already available in multicultural versions.

The construct presented allows the calculation of an overall level of the index using the combined average scores for the six elements of the index of educational or academic wellbeing. In other words, we can determine the level of protection versus risk of an individual or group on the basis of their scores. An individual who has an average aggregate protective scores will be above the 75th percentile on the overall index; an individual with a central average value will be between the 26th and 75th percentile and, finally, an individual on the 25th percentile and below will be at high risk. In each case, the levels of personal-contextual, teaching–learning and health correlate can be assessed. Those scores can be used to determine the correct path of intervention. In fact, the e-utility developed by proof of concept project (PDC2022-133145-I00) can be used to perform the calculation.

In conclusion, the index presented in this study can be an important tool for assessment and diagnosis in educational psychology in preuniversity and university settings in a similar way to other means of assessment in the same contexts [72–74], achieving a balance between academic excellence and wellbeing and satisfaction amongst students and to create a school ethos of wellbeing, as propounded by PISA 2022 [5]. Future research should gather fresh evidence, without forgetting the theoretical context and the generally applicable model which has given rise to the index and the e-coping tool developed to apply it.

4.1. Implications for the Education Sector of the EAWI

The EAWI arose from the observed need for those engaged in carrying out educational psychology assessments for a measurement tool that would be a step forward for evaluation and improve the teaching–learning process in schools in order to improve performance, student satisfaction with the teaching–learning process and student wellbeing.

In terms of practical implications for educational policy and praxis, it is a highly valuable instrument of primary and secondary prevention for educational psychologists. It supports the creation and maintenance of proregulatory educational settings that are well-structured and provide support to students, and so foster SR and personal autonomy in students. It also allows students to be encouraged to develop SR by adopting better time management and goal-setting strategies and practising their self-control skills.

Improving academic wellbeing requires boosting the SRL of students by adopting metacognitive strategies and appropriate study strategies and through increased motivation. In that sense, teaching praxis should focus on supporting positive emotionality, regulation of learning and student satisfaction, which in turn implies that teacher training should prioritise proregulatory teaching strategies. Student health should be supported by addressing the physical and mental needs of students by providing support resources and staff to promote overall wellbeing. The EAWI is offered as a useful tool for the assessment and improvement of academic wellbeing in students that will allow institutions to identify students’ individual and collective needs and so promote educational equity and strengthen the collaborative effort of teachers and allow them to adopt a holistic approach to students’ needs.

In sum, the EAWI contributes in a practical sense to improving the quality of student experience by providing a holistic view of the combined factors that predispose students to psychological wellbeing and flourishing in educational settings.

4.2. Relevance of the EAWI to the Personal Development of Mid and Late Adolescents

Although the sample for this study comprised late adolescents and young adults (18–25), we anticipate that future studies will consider the applicability of the EAWI in adolescents below the age of 18. The use of the EAWI to support personal development in adolescents requires that professionals understand and apply its multidimensional approach, which brings together personal, contextual and health factors. Specifically, the EAWI assesses aspects such as individual SR and the impact of the educational environment on student wellbeing. This in turn requires the creation of educational settings that promote individual autonomy and self-regulation, as well as providing the support and structures that adolescents need. The EAWI also considers regulation within the teaching–learning process, which requires assessment of SRL skills and the effectiveness of teaching methods. This underlines the importance of encouraging mid and late adolescents to be active participants in their own learning and of implementing classroom practice that supports positive emotionality and student satisfaction. The EAWI also assesses the impact of educational contexts on the physical and mental health of students and the need to provide intervention and support to address the health challenges that adolescents face. In summary, the implementation of the EAWI will allow teaching staff and institutions to create a fairer and more effective learning environment and so foment the optimal personal development and overall wellbeing of mid and late adolescents. In fact, the EAWI has given rise to the EBE Battery [44], a tool for the measurement and improvement of preuniversity and university education.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (10.13039/100014440) through projects PID2022 ref. 136466NB-I00 and PDC2022 ref. 133145-I00. Additional funding was provided by the Consejería de Universidad, Investigación e Innovación de la Junta de Andalucía within the program 54A (Scientific Research and Innovation) and the ERDF Andalusia 2021–2027 Program, within the Specific Objective RSO1.1 (Developing and improving research and innovation capabilities and assimilating advanced technologies) (Ref: P_FORT_GRUPOS_2023/66).

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.