Exploring the Predictive Role of Students’ Perceived Teacher Support on Empathy in English-as-a-Foreign-Language Learning

Abstract

The positive psychology turn in language education research has sparked increased scholarly interest in positive psychological variables among learners, such as empathy, which may contribute to their well-being and social networks. Empathy, shaped by both personal and environmental factors, can be influenced by a critical element in the learner’s immediate environment, namely, teacher support. However, the role of perceived teacher support (PTS) in fostering learner empathy remains underexplored. To address this gap, the present study investigated the structure of and relationship between the two constructs, with a sample of 748 Chinese high school English-as-a-foreign-language (EFL) students. Results of exploratory structural equation modelling (ESEM) confirmed the trifactorial structure of PTS in EFL students, consisting of academic, emotional, and instrumental support, and the unidimensional structure of learner empathy. Additionally, PTS and its subconstructs were found to be positively correlated with empathy. Multiple linear regression analysis further revealed that emotional and instrumental support together significantly and positively predicted learner empathy. Implications for enhancing teachers’ impact on learners were discussed.

1. Introduction

In the past two decades, more positive psychological variables were focused in language education, such as enjoyment [1], flow [2], resilience [3, 4], and buoyancy [5]. However, empathy, a crucial psychological factor that enhances well-being [6–8] and fosters positive social relationships [9], has received relatively limited attention. This construct, characterized by shared feelings and active support [10], is commonly understood as putting oneself in another person’s shoes and imagining their experiences as one’s own [11, 12]. The development of empathy not only fosters positive relationships and encourages constructive peer interactions [9] but also closely links to improve students’ English proficiency [11]. Studies have indicated that empathy, as an emotional interaction [10], can be shaped through social interactions within specific sociocultural contexts [13, 14].

Foreign language learning is a socialization process [15], where learners encounter hurdles and problems. Teachers, as significant others in students’ proximal social environment [16, 17], play a vital role in providing social support. The support provided by foreign language teachers not only aids students in overcoming academic hurdles but also fosters the development of competencies like empathy. Nevertheless, limited investigations have explored the intricate relationship between teacher support and empathy within the context of EFL learning. To address this gap, the present study considered PTS as a key environmental factor in fostering learner empathy.

To test this hypothesis, this study first sought to clarify the structure of these two constructs using the recently introduced ESEM approach. Building on this, it further examined the extent to which PTS predicted empathy among EFL learners. This endeavor to understand the structure of and interaction between these constructs is essential for advancing the existing knowledge in this area. Additionally, this insight may shed light on how different dimensions of teacher support contribute to learners’ mental development, offering valuable strategies for promoting empathy in language education.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Studies on Students’ Perceived Teacher Support

The essential role of social support provided by teachers has been consistently underscored by previous studies in mainstream education, where it fosters learners’ positive attitudes toward learning, enhances academic engagement, and optimizes learning outcomes [18, 19]. In the EFL context, teachers are similarly recognized for their significant impact on learners’ well-being and academic achievement [20, 21]. The demanding journey of acquiring and mastering a foreign language often exposes learners to challenges, such as foreign language anxiety and L1 interference [22, 23]. Given the inherently stressful feature of language learning, EFL teachers play a vital role in creating a motivating, supportive, and secure environment that promotes the continuous development of language proficiency [24, 25]. Despite extensive research on teacher support in mainstream education [26–29], EFL teacher support remains underexplored [21] and deserves further investigation, particularly for its role in influencing language achievement and emotional experiences [30].

In foreign language learning, teacher support is understood as a multidimensional construct [3]. This multifaceted concept is informed by two theoretical frameworks: self-determination theory and social support theory [31]. According to the self-determination theory, teacher support refers to cognitive, affective, and autonomy-oriented assistance perceived by students, encompassing three interrelated yet independent dimensions, namely, autonomy support, structure, and involvement [32]. From a social support perspective, teacher support involves providing informational, instrumental, appraisal, and emotional assistance to students [27]. Through this lens, Jiang et al. [33] developed a model of student-perceived teacher support in online contexts, categorizing it into emotional, social, intellectual, and instrumental dimensions. Similarly, Liu and Li [34], drawing on the social support framework, redefined EFL teacher support as comprising academic, instrumental, and emotional dimensions. Academic support involves subject-specific knowledge and feedback provided by teachers, while emotional support includes the trust, empathy, and care they extend toward students. Instrumental support pertains to the provision of supplementary learning materials such as textbooks, extracurricular reading materials, and online resources.

Liu and Li [34] also developed the Students’ Perceived EFL Teacher Support Scale (SPEFLTSS) and called for further empirical validation of its factor structure. In response to this call, the present study applied the ESEM to explore the structure of PTS among high school EFL learners in China. Previous studies on teacher support have typically used the traditional confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for validation (e.g., [16, 35]). However, CFA often encounters challenges such as poor item-level model fit and inflated interdimensional correlations [36]. ESEM, a popular alternative to traditional CFA [37], combines the strengths of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and CFA, offering more relaxed assumptions, a semiexploratory approach, easier model fitting, and a closer approximation to the true factor structure [38–41]. As such, from a technical perspective, ESEM is better suited for validating the structure of EFL learner PTS.

2.2. Studies on Students’ Empathy

“Social interaction is an inseparable part of dwelling in a social environment” ([12], p. 36). To navigate such interactions successfully, individuals need to be capable of showing concern for others. Empathy, as a relatively high level of concern [10, 42], is regarded as a key component of successful social interaction [43–45], which precisely refers to the ability to comprehend and appropriately respond to others’ emotions [11].

Extensive research in psychology and education has shown that highly empathetic individuals are more likely to perform favorable interactions [9] and establish positive relationships [46] and are less prone to aggressive behavior [1, 47] or burnout [7]. Furthermore, a substantial body of research highlights the significant association between empathy and various psychological variables, such as resilience [8] and boredom [48]. However, research on empathy within foreign language learning remains limited (e.g., [11, 49, 50]). For instance, Guiora et al. [50] found that empathy in foreign language learning was positively related to pronunciation authenticity. Kim T. and Kim Y. [11] reported that students’ empathy was significantly correlated with English proficiency, while Bao and Liu [49] suggested that empathy may help students with low self-esteem engage more actively in class. Additionally, Lei and Lei [51] found that empathy positively predicted creative self-efficacy and that both hope and empathy mediated the relationship between optimism in language learning and creative self-efficacy. Given the critical role of this concept in language learning, it is essential to further investigate the internal structure of this construct within language education and its relationship with other psychological factors.

2.3. The Prediction of Students’ PTS on Empathy in Language Learning

Research has shown that adolescents’ empathy is influenced by various individual factors (e.g., [52, 53]) as well as contextual factors (e.g., [54, 55]). For instance, empathetic responses can be shaped by personal past experiences [13, 17, 56]. Moreover, this construct as an emotional response to others’ feelings can develop when individuals feel accepted, understood, and supported [13, 57]. Support from educational environments—such as schools, peers, and teachers—plays a crucial role in fostering learners’ empathy [58, 59]. Among these external factors, teachers, as significant figures in proximal learning environments [17], can shape the growth of empathy by offering appropriate support, effective guidance, and high expectations. Numerous empirical studies show that students who perceive greater support from teachers experience more positive academic emotions and fewer negative ones (e.g., [60, 61]). Additionally, teacher support can be viewed as a specific manifestation of concern for students. This concern, stored in students’ subconscious through past experiences, can be activated when they encounter empathy-related emotional stimuli [13]. This process enables students to better understand others’ feelings, thereby fostering the development of empathy.

- 1.

What are the structures of EFL learner PTS and empathy?

- 2.

What are the levels of EFL learner PTS and empathy, and are there significant differences across grade levels?

- 3.

How does EFL learner PTS predict their empathy?

3. Method

3.1. Participants

A total of 748 senior high school students from Northeast China (302 males and 446 females) participated in the current study. However, 77 samples were deemed outliers (see Section 3.4), resulting in a valid sample size of 671 (see Table 1). All participants reported having Mandarin Chinese as their first language and were learning English as a foreign language.

| Male | Female | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Grade 1 | 133 | 43.2 | 175 | 56.8 | 308 | 45.9 |

| Grade 2 | 65 | 34.6 | 123 | 65.4 | 188 | 28.0 |

| Grade 3 | 65 | 37.1 | 110 | 62.9 | 175 | 26.1 |

- Note: N = 671.

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. EFL Learner PTS

The SPFLTSS [16] was utilized in this study to measure students’ perceptions of the support they obtained from their English teachers. This scale employed a 6-point Likert format ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree). It comprises three dimensions: academic support, emotional support, and instrumental support [16]. Academic support (Q1–Q5) encompasses both the subject-specific knowledge conveyed by EFL teachers in class and the feedback provided based on student performance (n = 5, α = 0.89; e.g., Q1: The English teacher carries out special teaching for our weak points [such as attributive clauses, etc.]). Emotional support (Q6–Q9) involves teachers’ demonstration of trust, empathy, love, and care towards students (n = 4, α = 0.90; e.g., Q6: The English teacher is very concerned about my study). Instrumental support (Q10–Q12) pertains to teachers’ provision of various supplementary learning materials to students, including textbooks, extracurricular reading materials, and online resources (n = 3, α = 0.88; e.g., Q10: The English teacher helps me choose suitable learning materials). The scale exhibited high internal consistency reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.93 for the entire scale.

3.2.2. EFL Learner Empathy

EFL learners’ empathy was measured by four items from the Student Academic Resilience in English Learning Scale (SARELS) [4]. These items came from the empathy subscale of L2 learner resilience questionnaire by Kim T. and Kim Y.’s [11] but were rephrased in Chinese to suit the EFL context in China (see Table S1). In addition, they have high reliability and validity (see [4]). Therefore, we used them in our study, where they exhibited good reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.89.

3.3. Data Collection

Data were collected using an online questionnaire distributed via Wenjuanxing from January to March 2023. After obtaining their online consent, students were invited to voluntarily complete the questionnaire. Participants were informed in advance that the data would be used solely for research purposes and that the study aimed to explore their English learning experiences. They were also assured that their grades and academic standing would not be affected and that no personally identifiable information would be disclosed.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using R 4.3.3, Mplus 8.3, and SPSS 26.0, comprising four stages. In the first stage, the researchers cleaned the data and assessed normality. R was used to identify and remove missing data and outliers, with multivariate outliers detected using the Mahalanobis D2 measure for all variables. According to the guidelines of Alamer and Marsh [62] and Hair et al. [63], the significance level was set at 0.001. Samples with D2 corresponding to a p-value below 0.001 were considered outliers and excluded, resulting in the removal of 77 cases, leaving a valid sample of 671 participants.

Next, data normality was assessed by examining both univariate and multivariate aspects. Univariate normality was evaluated through skewness and kurtosis tests, using cut-off values of ±3 and ±8, respectively, as recommended by Kline [64]. Multivariate normality was assessed using Mardia’s test [65], with p-values for both skewness and kurtosis required to exceed 0.05 to confirm multivariate normality. The univariate normality test results indicated that skewness values for each item on both scales fell within ±3 and kurtosis values were within ±8 (see Table S2). Thus, the data demonstrated univariate normality. However, results of Mardia’s test showed that the p-values for skewness and kurtosis were both below 0.05, indicating a lack of multivariate normality. In such cases, it is recommended to use estimators robust against nonnormality, such as maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR; [66]).

In the second stage, the researchers evaluated the construct validity of the SPFLTSS and empathy scale. Construct validity assessment involved examining factor structure, convergent validity, and discriminant validity [67]. First, following Liu and Li [34] and Kim T. and Kim Y. [11], ESEM was employed to validate the factor structures of both scales. Using a user-friendly ESEM code generation tool [68], the researchers obtained precise, tailored codes for analysis. In terms of model fit indices, the recommendations of Alamer and Marsh [62] were as follows: A comparative fit index (CFI) and a Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) close to 0.95 indicate good model fit, while values near 0.90 are considered acceptable. The root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) values of 0.07 or lower indicate acceptable fit, while values of 0.05 or lower suggest a good fit. Given the confirmatory nature of the study and the nonnormality of the data, we used MLR estimation with target rotation.

To assess convergent validity in the ESEM analysis, we examined the strength of item loadings on their respective factors, ensuring they significantly loaded onto the hypothesized factors [69]. Discriminant validity was supported if items hypothesized to load on one factor did not load significantly on other factors or if crossloadings were weaker than target loadings [62]. This stage of the analysis was conducted in Mplus.

In the third stage, descriptive statistics and one-way ANOVA were performed. Descriptive statistics were calculated for the PTS and empathy scores, and one-way ANOVA was used to explore whether significant differences existed across student grade levels. The statistical and practical significance of intergroup differences was assessed through p-values and η2 values. Based on Cohen’s [70] thresholds, η2 values of 0.01, 0.06, 0.14, and 0.2 represent small, medium, large, and very large effect sizes, respectively.

In the fourth and final stage, multiple regression analysis was run to examine the predictive effects of the three dimensions of students’ PTS on empathy. This stage, along with the previous one, was carried out in SPSS.

4. Results

4.1. RQ1: Structures of EFL Learner PTS and Empathy

4.1.1. Three-Dimensional Structure of EFL Learner PTS

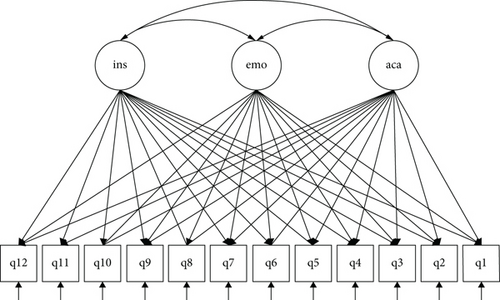

ESEM was run to examine whether the trifactorial structure of the students’ perceived support from their English teachers fit the data in the current sample (see Figure 1). The ESEM results further confirmed that the trifactorial model with 12 items showed a good fit, further confirming the results of Liu and Li [34]. Specifically, the RMSEA and SRMR were 0.045 and 0.017, respectively, and the CFI and TLI were all greater than 0.90 (CFI = 0.984, TLI = 0.968). The values reached the cut-off scores mentioned above.

All 12 items significantly loaded on their hypothesized factors, with factor loadings all greater than 0.50, demonstrating good convergent validity. Discriminant validity was also supported (see Appendix Table A1), as all crossloadings of the items in the ESEM model were either nonsignificant or smaller than the target item loadings.

4.1.2. Unidimensional Structure of EFL Learner Empathy

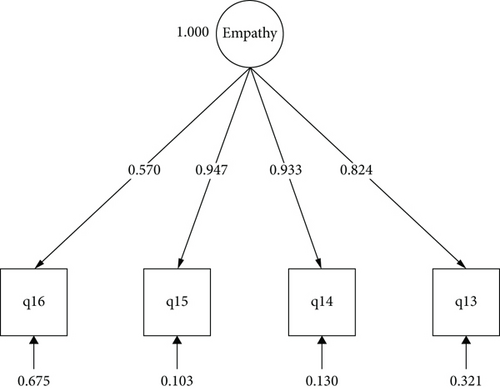

ESEM was run to examine whether the unidimensional structure of the students’ empathy fit the data in the current sample (see Figure 2). The ESEM results confirmed that the unidimensional model with four items showed an acceptable fit. Specifically, the RMSEA and SRMR were 0.054 and 0.013, respectively, and the CFI and TLI were 0.996 and 0.988, respectively. The values reached the cut-off scores mentioned above.

All the items were significantly loaded on the hypothesized factor, with all the factor loadings exceeding 0.50 (see Figure 2), supporting its convergent validity. Owing to the unidimensionality, the discriminant validity was not examined.

4.2. RQ2: Levels of EFL Learner PTS and Empathy

Both scales used were 6-point Likert scales, with a median score of 3.5. A mean score above the median indicates high levels of PTS and empathy, while a mean below the median indicates lower levels.

4.2.1. High Levels of EFL Learner PTS

Descriptive statistics for students’ PTS (see Table S3) revealed an overall mean of 5.52 (SD = 0.62), suggesting that students reported a high level of perceived support from their English teachers. Among the three dimensions of PTS, academic support had the highest mean (M = 5.72, SD = 0.48), followed by emotional support (M = 5.51, SD = 0.71). Instrumental support had the lowest mean (M = 5.22, SD = 1.00). However, all three dimensions had mean values above 3.5, indicating consistently high levels of PTS across all dimensions.

No statistically or practically significant difference was found in overall teacher support (p = 0.068, η2 = 0.008) across the three grade levels (see Table S4). There was also no significant difference in academic support (p = 0.461, η2 = 0.002) among students of different grades. Although emotional support (p = 0.045, η2 = 0.009) showed a barely statistically significant difference, the effect size (η2 less than 0.01) was negligible, rendering the difference practically irrelevant. Instrumental support, however, did exhibit a significant difference across grades with a small effect size, just reaching the threshold for practical significance (p = 0.034, η2 = 0.010). Tukey’s post hoc analysis indicated that second-year students perceived significantly higher instrumental support than first-year students.

4.2.2. Moderate-to-High Levels of EFL Learner Empathy

The average score for students’ global empathy was 4.30 (SD = 1.22) (see Table S5), indicating that students displayed a moderate to high level of empathy in English learning. This result aligns with Lei F. and Lei L. [51], who also found moderate to high levels of empathy among Chinese university EFL students. There was no statistically or practically significant difference in empathy scores across the three grades (p = 0.209, η2 = 0.005; see Table S6), indicating that students in all grades maintained consistently high levels of empathy.

4.3. RQ3: Prediction of EFL Learner PTS on Empathy

The multiple linear regression analysis conducted in this study met the key assumptions of independent samples (DW = 1.861, close to 2), absence of multicollinearity (VIF < 5), and normal distribution of residuals (see Figure S1). Significant positive correlations were found between empathy and the three dimensions of teacher support, indicating a strong positive relationship between the independent variables and the dependent variable. Specifically, the correlation coefficient between empathy and teacher academic support was 0.343 (p < 0.05), between empathy and teacher emotional support was 0.440 (p < 0.05), and between empathy and teacher instrumental support was 0.463 (p < 0.05) (see Table S7).

| R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | DW | F (3, 667) | β | t (667) | Tolerance | VIF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV | Empathy | 0.484 | 0.235 | 0.231 | 1.861 | 68.187 ∗ | ||||

| IV | Aca | −0.009 | −0.171 | 0.461 | 2.167 | |||||

| Emo | 0.219 | 3.805 ∗ | 0.346 | 2.889 | ||||||

| Ins | 0.305 | 5.850 ∗ | 0.422 | 2.369 | ||||||

- Note: N = 671; DW = Durbin–Watson statistic; Aca = academic support; Emo = emotional support; Ins = instrumental support.

- Abbreviations: DV = dependent variable; IV = independent variable.

- ∗p < 0.05.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

This study sought to explore the predictive role of students’ PTS in their empathy in EFL learning, as well as to examine the structures and levels of these constructs among Chinese senior high school students.

The findings revealed that students’ PTS demonstrated a trifactorial ESEM structure, comprising academic, emotional, and instrumental support, while their empathy exhibited a unidimensional ESEM factor structure. The three-factor structure of students’ PTS and the unidimensional structure of their empathy are consistent with the findings of Liu and Li [34] and Kim T. and Kim Y. [11]. The satisfactory fit of the three-factor ESEM model of students’ PTS suggests that items in the SPFLTSS not only represent their corresponding latent variables but also correlate with other latent variables conceptually related to their target latent variables [71, 72]. This model may more accurately reflect the actual structure of students’ PTS, as nonzero crossloadings are inherent in psychological measures and can often be logically anticipated from the nature of the items themselves [36, 37]. However, crosscultural research highlights that culturally specific factors influence how individuals interpret and respond to these constructs [73, 74]. Thus, further empirical research across diverse populations is needed to confirm whether the three-factor model generalizes to other contexts.

Descriptive analysis indicated that participants perceived a high level of teacher support, slightly higher than what was reported by Zhao and Yang [21], where most Chinese high school students reported moderate levels of support. This discrepancy could be attributed to regional sampling differences. Moreover, no statistically significant differences were observed in total teacher support across grade levels. This could be linked to China’s unique educational environment, where schools provide a comprehensive support system for all students [75]. The significant difference in perceived instrumental support across grades may reflect the changing focus of instruction at different stages. In the first year of high school, teachers help students adapt to the new environment [76, 77], while in the second year, the emphasis shifts to refining study strategies and improving academic performance, which often involves providing additional learning resources.

Participants’ levels of empathy were moderate to high, consistent with Lei and Lei’s [51] findings regarding foreign language learners in Chinese universities. Besides, there was no statistically or practically significant difference observed in students’ empathy scores among different grade groups. The lack of significant differences in students’ empathy among student grades may be related to Chinese community culture, where classrooms function as communities where students study and interact with each other [78], enabling them to better perceive others’ feelings, express thoughts effectively, and guide conversations appropriately in English based on the particular context or interlocutor.

The three dimensions of students’ PTS were positively associated with their empathy, with greater perceived emotional and instrumental support from teachers significantly predicting higher levels of empathy. This finding supports the idea that environmental factors, such as teacher support, shape empathy development by providing students with experiences of concern and support [13, 14]. It also partially echoes prior studies (e.g., [60, 61]) showing that teacher support impacts students’ emotional experiences. Interestingly, we noted that among the three dimensions of teacher support, academic support did not have a significant impact on students’ empathy. This may be because students perceive the delivery of subject-specific knowledge as a teacher’s responsibility [79], rather than an act of concern, thus having no significant effect on their empathy in our study.

This study has both theoretical and practical significance. Theoretically, it confirmed the three-factor structure of PTS using ESEM, reinforcing the tridimensional nature of teacher support as proposed by Liu and Li [34] and further clarifying its internal structure. The study also explored the impact of the three dimensions of PTS on students’ empathy, addressing gaps in the research on the relationship between these constructs. Practically, this study examined the levels of PTS and empathy among Chinese high school students, providing valuable feedback for researchers, policymakers, and educators regarding educational quality. The findings suggest that teachers can enhance students’ perception of support by providing academic, emotional, and instrumental assistance, thereby fostering empathy development and further improving language learning outcomes.

Nevertheless, this study acknowledges several limitations. First, the generalizability of the findings may be limited, as the participants were students in the secondary education phase within the specific context of China’s educational system. Future research could expand the sample to include higher education contexts, such as universities, vocational schools, and beyond. Additionally, crosscultural differences in students’ perceptions of teacher support and empathy should be considered. Researchers may better capture more context-specific feature of student variables by conducting crosscultural studies with students from diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. Second, the complex dynamics of the variables investigated in this study remain underexplored due to the use of a cross-sectional research design. A longitudinal design would allow researchers to track the development of learners’ perceptions of teacher support and empathy over time. Finally, the influence of other factors on learner empathy has yet to be explored, as this study focused specifically on the predictive effect of perceived teacher support. Future research could enrich the literature by examining how a variety of personal and social factors (e.g., personality traits, family, and peer support) impact learner empathy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

There is no funding for this paper.

Appendix 1

| Items | Academic support | Emotional support | Instrumental support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 The English teacher carries out special teaching for our weak points (such as attributive clauses, etc.). | 0.806 ∗ | 0.002 | 0.027 |

| Q2 The English teacher teaches us how to compensate for limited knowledge (such as guessing meanings from the context, etc.). | 0.786 ∗ | 0.093 | 0.086 |

| Q3 The English teacher teaches us the pronunciation of words, fixed usage, etc. | 0.908 ∗ | 0.058 | −0.062 |

| Q4 The English teacher expands our extracurricular cultural knowledge related to the textbook content. | 0.576 ∗ | 0.133 | 0.107 |

| Q5 The English teacher teaches us practical knowledge (such as writing sentence patterns, etc.). | 0.729 ∗ | 0.086 | −0.019 |

| Q6 The English teacher is very concerned about my study. | 0.057 | 0.929 ∗ | −0.102 |

| Q7 The English teacher is very patient with me and will not give up on me even if my basis is poor. | 0.075 | 0.987 ∗ | −0.188e |

| Q8 The English teacher has high expectations of me. | −0.122 ∗ | 0.688 ∗ | 0.247 ∗ |

| Q9 The English teacher understands the difficulty of my English learning. | −0.013 | 0.666 ∗ | 0.233 ∗ |

| Q10 The English teacher helps me choose suitable learning materials. | 0.063 | 0.038 | 0.811 ∗ |

| Q11 The English teacher helps me choose suitable extra-curricular reading materials. | 0.068 | 0.000 | 0.873 ∗ |

| Q12 The English teacher shares with me online learning resources (such as word memorization software, etc.). | 0.104 | 0.182 | 0.531 ∗ |

- Note: N = 671. Bold values indicate target factor loadings, reflecting the primary association strength between variables and their theoretically hypothesized latent constructs. Nonbold values represent nontarget factor loadings, indicating secondary associations of variables with nontarget latent constructs, consistent with ESEM’s exploratory design that permits cross-loadings.

- ∗p < 0.05.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data generated during the current study will not be openly available due to sensitivity concerns and are available only from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.