Unveiling Vulnerability Determinants Among Migrant-Background Students: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Since 2015, the increasing influx of migrant children into European Union countries has raised critical questions regarding their access to equitable education. This fact has highlighted the necessity to examine and systematize the vulnerability determinants that contribute to their socioeducational disadvantages. This systematic literature review explores the vulnerability factors or determinants influencing migrant-background children’s academic underachievement and early school leaving (ESL). Employing the PRISMA approach and utilizing Covidence software for data collection, 74 articles were reviewed. Guided by Bronfenbrenner’s ecological framework, vulnerability determinants were classified into micro-, meso-/exo-, and macrosystemic levels. The review reveals a predominant focus in the literature on microlevel factors, with only limited attention to macrolevel determinants. These research findings underscore the need for further exploration of macrolevel factors and call for a greater focus on intersectionality when addressing migrant-background students’ socioeducational vulnerabilities.

1. Introduction

The crises at the European Union’s borders, starting with the Arab Spring in 2011, followed by the “long summer of migration” in 2015 [1, 2], and further intensified by the 2021 Ukrainian war [3], have significantly increased the presence of nonnational children in EU countries. As defined by Article 1 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child [4], a child is any individual under the age of 18. According to the European Commission [5], between 2014 and 2023, the population of nonnational children grew by 52.6%, reaching nearly eight million in January 2023, while the population of national children decreased by 4.4%. These demographic shifts have led to substantial transformations in the composition of European schools and classrooms [6]. As a result, persistent questions have been raised [7–9] regarding the ability of the European educational systems to provide migrant-background students with an education that supports their “fullest possible social integration and individual development,” as articulated by Article 23 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child [4].

Unless otherwise specified, the term migrant background is used throughout this paper as an umbrella concept referring to individuals who have moved, or are moving, across international borders or within a country away from their habitual place of residence—regardless of legal status, voluntariness of the movement, underlying causes, or duration of the stay [10].

Despite the critical role of education in integrating migrant-background children into their new societies, many of these students face vulnerabilities that adversely affect their academic performance and increase the risk of early school leaving (ESL) [11, 12]. Factors such as language barriers, socioeconomic status (SES), family structure, and the psychological impact of migration contribute to their educational disadvantages [12, 13]. To create an environment conducive to the intellectual and social development of these children, a comprehensive understanding of the factors that either promote or hinder academic success is essential. In 2016, a systematic review was published examining the literature from 1996 to 2015, which identified key challenges faced by refugee students, focusing on both individual- and school-level factors [14]. However, given the changing in the scenario since 2015, as well as the evolving needs of children with migrant backgrounds, there is a need for a more up-to-date review to address and complement our understanding of their socioeducational vulnerabilities.

This paper is aimed at filling this information gap by systematically analyzing the vulnerabilities experienced by migrant-background students, from kindergarten through secondary school, regarding their academic underachievement and ESL, as documented in the existing literature from 2015 to 2023. The central research question guiding this review is as follows: What are the factors associated with migrant-background children’s vulnerability to academic underachievement and ESL?

By applying the conceptual lens of vulnerability to the academic trajectories of migrant-background students, this study is aimed at identifying the key socioeducational challenges that hinder their achievement and increase the risk of ESL. This study represents a unique contribution to the literature as previous research has primarily focused on examining vulnerabilities of migrant-background children within clinical contexts (see [15–21]), with limited exploration of their interaction with the education sector (see [22]).

The structure of the paper is as follows: First, we present the multifaceted concept of vulnerability and its application to understanding the socioeducational vulnerabilities faced by migrant-background students. Furthermore, the concepts of underachievement and ESL are outlined, highlighting their significance as metrics of educational disadvantages. Next, we describe the methodological decisions underlying our systematic literature review, including the syntax terms and inclusion criteria used. The results are presented to offer a systemic perspective that organizes vulnerability determinants across different levels and dimensions. In the Discussion section, we contextualize the key insights within the broader literature.

2. The Vulnerability Concept

Defining the concept of vulnerability is a complex undertaking and has been the object of political and sociological debates during the last two decades. Scholars, policymakers, and mass media have increasingly employed the term since the 1990s [23–29]. Although it is treated in many contexts as a self-explanatory condition [30], the accurate definition of vulnerability remains a significant challenge for academic and societal discourse [31, 32]. Some academics resist its use due to its attribution of inherent weaknesses in specific groups, especially when linked to the concept of “limited capacity” [30], which might lead to stigmatization [24, 30]. However, from a political perspective, a well-defined concept of vulnerability has the potential to contribute to developing more effective and responsive policy frameworks [33].

The United Nations Division of Social Policy and Affairs refers to vulnerability as “a state of high exposure to uncertain risks, combined with a reduced ability to protect or defend oneself against those risks and cope with negative consequences” (p. 201) [34]. In broader terms, vulnerability encompasses certain conditions that increase the likelihood or risk of experiencing disadvantages or adverse outcomes [28]. Despite these definitions, the concept of vulnerability remains poorly delineated in specific contexts [35], such as education, which is the focus of this systematic review. Thus, our approach is rooted in established theoretical frameworks that provide a multifaceted and comprehensive view of the concept when referring to the migrant-background populations in educational settings. Figure 1 offers a comprehensive conceptualization of vulnerability.

Our core vulnerability concept integrates three of the five dimensions outlined by Brown et al. [39], which have also been adopted by Gilodi et al. [30] specifically for migrant-background populations.

Brown et al.’s [39] categorization of vulnerabilities is particularly relevant as it tackles the central debate in the literature on whether vulnerability emerges from external risks or internal defenselessness [43]. The five vulnerability dimensions identified by Brown et al. [39] are (1) natural or innate vulnerability; (2) situational vulnerability; (3) vulnerability as related to social disadvantage, the environment, and/or geographical spaces; (4) universal vulnerability; and (5) vulnerability as closely related to risk. When applied to migrant-background populations, as argued by Gilodi [30], (1) to (3) are the most relevant.1

The category of innate vulnerability has traditionally been understood as stemming from incomplete maturity and lack of agency and has been commonly is associated with childhood, elderly, and people with disabilities [28, 30, 39]. This form of vulnerability typically refers to a natural susceptibility to harm [50, 51] and the inability to defend oneself [52] due to “natural” characteristics. Moreover, in the case of adolescents, developmental psychology perspectives have characterized youth vulnerabilities, often marked by an identity crisis [53]. However, this essentialist view has been increasingly challenged by a more critical perspective that questions the assumption of vulnerability as a fixed, biological determined condition. Scholars argue that vulnerability is not solely rooted in the body or age, but is socially and relationally constructed, emerging from contextual, institutional, and structural dynamics [39, 54]. This shift in understanding emphasizes that children, elderly individuals, and persons with disabilities are not inherently vulnerable, but can become vulnerable through their interactions with environments and systems that limit their agency to fail to accommodate their needs.

Situational vulnerability is tied to specific circumstances and pertains to individuals facing challenging experiences or social adversities. Unlike innate vulnerability, this type of vulnerability is subject to change over time and has a relational dimension since it arises from the situational interaction “between circumstances and personal characteristics” [32]. It often applies to groups necessitating special assistance, such as asylum seekers, refugees, impoverished individuals, or ethnic minorities. In this context, “vulnerability” highlights experiences requiring both protective and proactive policy frameworks, as it encompasses structural components, personal choice, and agency [30, 55, 56].

Bozdag [57] further explored the concept of the situational dimension of vulnerability when specifically applied to migrant-background populations and distinguished between (1) spatial vulnerability, (2) sociopolitical vulnerability, and (3) sociocultural vulnerability. Spatial vulnerability, commonly observed among undocumented migrants, emerges from environmental risks and difficult living conditions during migration. Sociopolitical vulnerability is rooted in the absence of legal status, resulting in limited access to rights and services, contributing to economic vulnerability. Sociocultural vulnerability, influenced by legal status and ethnic origin in the country of transit or destination, encompasses obstacles such as language barriers, social exclusion, and limited livelihoods.

Finally, social/environmental vulnerability revolves around varying exposure to poverty, hazards, and the impacts of globalization. It is frequently used in the case of natural disasters, where different populations are more or less affected. An example of vulnerability related to the environment and geographical spaces is provided by Pelling [40], who explores the vulnerability and resilience of the local population across three distinct cities in the Global South. On the other hand, vulnerability related to social disadvantage involves material shortages, inability to meet needs, and uncertain reliance on welfare services, highlighting intergenerational disadvantage patterns [36, 39].

In order to understand how the vulnerability determinants work in an integrated and structured system, we adopt an ecological perspective [37, 38, 58] as applied by Leonard [59], McKown [60], and Shams [61]. This framework allows us to categorize the determinants of vulnerability at the microsystem (personal characteristics and immediate environment with its significant relationships, such as school, home, and peers), meso-/exosystem (relationships and environments indirectly influencing students, such as parental involvement, school districts, and neighborhoods), and macrosystem level (structural influences such as societal, cultural, and economic conditions).

2.1. Determinants of Migrant Children’s Vulnerability Concerning Educational Outcomes

In the context of educational outcomes and disadvantages, this study focuses on two metrics: the academic underachievement of students and ESL. In a conceptual sense, academic achievement refers to accomplishing predefined learning objectives [62]. Conversely, academic underachievement refers to a significant difference between the anticipated level of achievement (as determined by cognitive or intellectual ability assessments and standardized test scores) and the actual performance (as reflected in class grades and teacher evaluations) [63]. On the other hand, ESL involves the complete discontinuation of formal education [64].

Academic underachievement and ESL metrics provide a comprehensive understanding of the educational experience of migrant-background children for various reasons. Firstly, these two metrics combined comprehend behavioral, cognitive, and emotional academic engagement, which is crucial in predicting overall academic performance [42]. Secondly, the supposed objectivity of grades and the tangible consequences of ESL provide concrete insights into the challenges and successes faced by migrant-background students, guiding decisions about further education and future career paths. Finally, utilizing these measures goes beyond mere statistics; it fosters a well-rounded and informed approach to addressing the diverse educational needs of migrant-background students.

The determinants of vulnerability faced by students with migrant backgrounds can be categorized based on their proximity to the individual following the ecological perspective [65].

Microlevel or proximal factors for underachievement include host country language proficiency, which affects both reading skills and emotional well-being (depression and low self-esteem) [66–68] as well as the perception of discrimination especially for second-generation migrants more aware of discriminatory practices, as highlighted by Mezzanotte [6]. SES, frequently lower among migrant-background populations, appears to have a more pronounced effect on academic performance than merely having a migrant background [69]. Another critical factor is the duration of residence in the host country, as shorter durations are associated with poorer performance [41].

Conversely, a factor that can mitigate academic underachievement is the early enrollment of migrant-background children in preschools within the host country [69]. Yet their involvement in nonparental childcare is lower than that of native children [7].

Regarding ESL, the OECD [6] pinpointed membership in migrant-background groups as a risk factor for school dropout. In Europe, the likelihood of leaving compulsory education is twice as high for individuals in migrant-background groups compared to native populations [7]. While there is a lack of data regarding the reasons for ESL among second-generation migrant students, available information for first-generation migrant children indicates that factors contributing to ESL include schools’ failing to meet their needs or interests (31%), opting to start working (19%, especially in Spain), facing study difficulties (13%), and family reasons (11%) [70].

At the meso-/exolevel, the composition of classes and schools plays a pivotal role, as the academic performance of migrant-background students is lower when they are in a school or classroom where most of the students also have migrant backgrounds [71–73]. The well-being of migrant-background students is adversely affected by the school’s low SES and an unwelcoming environment. This impact, measured by the proportion of students facing bullying or feeling alienated, influences their integration into the education system and, consequently, their academic achievement [70]. Indeed, Hillmert’s [74] explanatory model highlights the role of both favorable and nonfavorable developmental environments, including institutional support and language training [75]. Early tracking systems pose a barrier that hinders academic achievement [69].

At the macrosystem level, policies and practices that promote social integration, cultural diversity acceptance, and equity efforts are promising strategies to mitigate the commonly found migrant-background student academic disadvantages [72]. Findings by Dronkers et al. [76] and Schlicht-Schmälzle and Möller [77] indicate that the effectiveness of integration policies, such as access to the labor market and antidiscrimination laws, as well as the degree of democracy within the political–institutional context, plays a significant role. Additionally, the structure of the educational system, including factors like early tracking and selection, the duration of compulsory education, and the availability of educational resources, critically influences the academic success of migrant-background students.

For refugee children, the situation is more intricate. Even though they gain access to the educational system, their outcomes and needs remain obscure, as they are not captured in their home country’s educational management information systems and are yet to be included in their host countries [78]. These children encounter additional challenges relating to integration barriers at different systemic levels, including distrust of government programs at the microsystem level and bureaucratic complexities at the macrosystem level [7].

3. Current Study

This systematic review is aimed at exploring how the vulnerability factors associated with children’s migrant backgrounds influence their academic underachievement and ESL.

Two key conceptual decisions have been made to analyze and expose our results systematically. The first conceptual choice pertains to the categorization of the migrant-background populations. Despite the acknowledged risk of overgeneralization in grouping migrants [79–81], we deemed it useful for the coherence of the analysis narrative. Given that differences in nativity, both for oneself and one’s parents, significantly impact acculturation processes within migrant-background families [82–86], we classify the migrant-background populations into three main categories based on the birthplace. First-generation migrants are children born and raised in a country different from their parent’s country of origin. Second-generation migrants are native-born children with foreign-born parents [87]. There is an ongoing debate on whether to categorize refugees as first-generation migrants or as a distinct group of individuals who have moved to seek international protection [88]. In our study, we consider refugees as a separate group to explore potential unique experiences of disadvantages.

The second conceptual decision involves the classification of the vulnerability determinants identified in the literature according to Bronfenbrenner’s three ecological levels [37, 38, 58].

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.1.1. Eligibility Criteria

The search for articles in this systematic review was conducted in June 2023 using the Scopus database.2 Our search covered empirical articles published between 2015 and 2023. We chose this start date for two main reasons: on one side, because of 2015’s unparalleled and unregulated influx of people daily crossing EU borders in pursuit of security and improved living conditions [89]. As the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [90] reported, in 2015, more than one million people crossed the EU borders, arriving by boat from North Africa and Turkey. On the other hand, the most recent study that reviewed vulnerability factors associated with academic underachievement and ESL among migrant-background students was published in 2015, covering literature from 2000 to 2015 [12]. All articles are peer-reviewed and searched exclusively in English, which is regarded as the commonly accepted academic language.

3.1.2. Search Strategy

This systematic review followed the PRISMA principles, which offer a guide for systematic literature review studies [91]. The PRISMA approach proposes a set of specific procedures designed to improve the transparency, consistency, and high-standard quality in reporting systematic reviews and meta-analysis results in academic research.3 For the search strategy, we used the PICO framework, a structured approach commonly used in evidence-based healthcare and research to formulate a focused clinical or research question [92]. Given the conceptual nature of this systematic review, the selection of terms focused predominantly on defining the population (migrant-background children) and the outcome of interest (academic results, academic underachievement, and ESL). The search terms for this study were selected during a systematic review conducted as part of the European project (LET’S CARE). Additionally, several scholars and experts from different fields and countries provided supervision during the term selection process. The selected terms were intended to locate articles elucidating the relationship between being a migrant-background child and succeeding or not succeeding in school.

Table 1 presents the selected search terms. In the first column, we focused on characterizing the population of interest, specifically individuals with a migrant background. The second column refers to the status of the subjects under consideration, where the term “teacher” was included to broaden the scope and encompass relevant articles. The third column represented the targeted outcomes for the study, specifically focusing on academic result, academic underachievement, and ESL in this context. The columns were interconnected through the “AND” operator in the search, ensuring that at least one term from each axis was present concurrently in the search outcomes. The search strategy was executed using keyword research.

| Migrant background | Population | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

|

Student | Attainment |

| OR refuge∗ | OR child | OR “academic achievement” |

| OR foreign∗ | OR pupil | OR “school achievement” |

| OR teacher | OR “academic underachievement” | |

| OR “school underachievement” | ||

| OR “academic results” | ||

| OR “academic performance” | ||

| OR “academic grades” | ||

| OR “academic failure” | ||

| OR “school outcomes” | ||

| OR “academic outcomes” | ||

| OR “learning outcomes” | ||

| OR “learning process” | ||

| OR drop-out | ||

| OR drop out | ||

| OR “drop-out” | ||

| OR “school development” | ||

| OR “academic development” | ||

| OR “school engagement” | ||

|

3.1.3. Study Screening

- •

Did not address vulnerability and/or mitigating factors among migrant-background children;

- •

Focused on university-based contexts rather than school settings;

- •

Were not written in English (beyond the abstract);

- •

Focused primarily on the use of digital tools in education;

- •

Examined internal migration (e.g., Chinese left-behind children);

- •

Addressed nutrition or medical topics;

- •

Focused on the impact of migrant-background students on nonmigrant peers rather than the experience of the migrant-background students themselves.

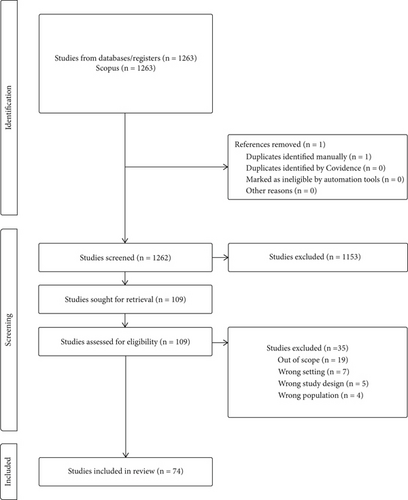

This systematic review employed a double-blind process, with two reviewers overseeing all article selection phases. For the initial screening, we utilized the Covidence software, a web-based collaboration software platform that streamlines the production of systematic and other literature reviews.4 Given that we only accessed the Scopus database, no duplicate records were flagged by the software. However, one duplicate was manually identified by one of the reviewers. Two reviewers independently performed the subsequent eligibility screening, with any discrepancies settled through discussion. An illustrative summary of this process is visually depicted in Figure 2 (PRISMA diagram; Page et al. [93]), ultimately including 74 articles in this review.

- •

Nineteen were considered out of scope since they primarily focused on students’ mental health outcomes, school engagement, or adjustment, which are more self-rated evaluations, and did not consider objective indicators of academic underachievement, such as grade point average (GPA) or test results provided by the teacher, and did not investigate the relationship between vulnerability factors and underachievement or ESL.

- •

Seven studies had a setting that did not fit with the scope of this systematic review, as they revolved around a refugee camp rather than a school context or investigated upper-educational settings.

- •

Five works had a study design that did not fit with the scope of this systematic review, such as literature reviews or theoretical reviews.

- •

Four studies featured a population that did not fit with the scope of this systematic review, focusing on teachers’ perspectives on an intervention program or considering a sample of nonmigrant children.

3.1.4. Data Extraction and Mapping

In the final stage, 74 articles were extracted. In cases where conflicts or discrepancies emerged, discussions were held to reach a consensus.

The extraction phase was conducted using Covidence, which involved an extraction template encompassing various aspects of the articles. This template included information such as general article details (authors, publication year, DOI, and title), sample information (country, migrant backgrounds’ country of origin, sample size, age, and school level), vulnerability aspects (type of migrant backgrounds, presence or absence of a vulnerability definition, and utilization of vulnerability proxies if a definition was not provided), study design details (research design and technique type), and results (a matrix outlining the relationship between significant variables and their correlation with [under]achievement). The template structure was determined through consensus with two experts in the field. The structure is designed to systematically gather essential information relevant to the goals of the review, namely, to map the determinants of vulnerability experienced by migrant backgrounds about academic results. Additional information was collected to offer insights into the contexts and methodologies employed in the various studies. Subsequently, the collected information was exported to an Excel file for further analysis and evaluation.

4. Results

4.1. Overview of the Articles

The geographical areas covered by the 74 articles included in the systematic review are concentrated in the United States and Canada (31) and in the European context (30). Additionally, five articles are developed in the Middle East, three in Oceania, and two in Asia. Three studies stand out for their wide international coverage of OECD countries, drawing upon the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) datasets.

The majority of the articles (63 out of 74) employ a quantitative design, comprising 32 cross-sectional and 31 longitudinal studies. Nine articles adopt a qualitative methodology, while two articles use mixed methods. Among the quantitative articles, the majority (49 out of 63) have sample sizes exceeding 1000, with only nine articles featuring sample sizes below 500. Qualitative articles exhibit sample sizes ranging from 8 to 65, and the two mixed method articles have sample sizes of 80 and 189.

Regarding population coverage, 43 articles are grounded in the context of secondary schools, and 11 encompass both primary and secondary schools. Another 11 articles are drawn exclusively from the primary school context. The remaining nine articles focus on preschool and elementary school contexts. Regarding the population of interest, more than half of the studies (46 out of 74) do not distinguish between migrant generations. They analyze the experiences of students with different migrant backgrounds without distinction. Additionally, six articles focus on the challenges faced by refugees, 15 articles on the experiences of first-generation migrants, and the 15 remaining articles delve into the second-generation migrant population and beyond. With a few exceptions, the majority of these migrant-background children are situated in the Global South [94]. All the details are reported in Table 2.

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Country | ||

| United States and Canada | 31 | 42% |

| Europe | 30 | 40% |

| Middle East | 5 | 7% |

| Oceania | 3 | 4% |

| PISA’s countries | 3 | 4% |

| Asia | 2 | 3% |

| Methodology | ||

| Quantitative | 63 | 85% |

| Cross-sectional | 32 | 51% |

| Longitudinal | 31 | 49% |

| Qualitative | 9 | 12% |

| Mixed method | 2 | 3% |

| Population | ||

| Sample | ||

| Quantitative methodology | ||

| < 500 | 9 | 14% |

| 500 < N < 1000 | 5 | 8% |

| > 1000 | 49 | 78% |

| Qualitative methodology | 8 ≥ N ≤ 65 | 100% |

| Mixed method | 80; 189 | 100% |

| School level | ||

| Primary school | 11 | 15% |

| Secondary school | 43 | 58% |

| Prekindergarten to primary school | 2 | 3% |

| Kindergarten to primary school | 3 | 4% |

| Kindergarten to secondary school | 3 | 4% |

| Primary and secondary school | 11 | 15% |

| From secondary onward | 1 | 1% |

| Migrant status | ||

| Refugees | 6 | 8% |

| First generation | 11 | 15% |

| Second-generation, ethnic minority | 11 | 15% |

| Unspecified | 46 | 62% |

The following sections will systematically address the determinants of vulnerability identified in the selected articles that contribute to academic underachievement and ESL among students with migrant backgrounds. These determinants will be discussed separately within the context of micro- and meso-/exosystems, emphasizing variations among first-generation migrants, second-generation migrants (ethnic minorities), and refugees. Table 3 shows a summary of these determinants. For supporting information, refer to Table S1 (“Characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review, including number and age of participants, country of the study, aim, and migrant cohort”) in the Supporting Information section. The scarcity of literature on macrosystem dimensions will be acknowledged in the Discussion section.

| Level | Sublevel | Vulnerability determinants | Mitigating factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microlevel | Student’s personal attribute |

|

|

| Family-derived factors |

|

|

|

| Relationships with peers and teachers |

|

|

|

| Meso-/exolevel |

|

|

|

4.2. Determinants of Vulnerability in Relation to Academic Underachievement and ESL

4.2.1. A Microsystem Analysis

The analysis of the articles revealed a predominant presence of vulnerability factors at the microsystem level compared to the other systemic levels. For their presentation, we have categorized them into three main categories: personal student attributes, family-derived factors, and other proximity factors, such as relationships with peers and teachers.

4.2.1.1. Student’s Personal Attributes

Among the personal student attributes, language proficiency in the destination country emerges as a shared challenge among all categories of migrant-background students. Fourteen studies highlight the negative impact of having the destination country’s language as a second language on academic achievement for first- and second-generation migrant students [95–107]. For refugees, Karkouti et al. [108] and Tonsing [109] emphasize the lack of language proficiency as a barrier to academic achievement. Conversely, proficiency in the destination country’s language emerges as a catalyst for improved academic performance for all migrant-background students, as shown by 10 studies [109–118]. Also, balanced linguistic and cultural integration is crucial for first-generation migrant students’ academic success [100, 105], while second-generation migrant students are found to benefit from balancing mainstream culture with connections to specific communities [114, 119, 120].

Well-being factors, such as mental health challenges, particularly depressive symptoms and posttraumatic disorders (PTSDs) due to the circumstances of migration, are other common determinants among first- and second-generation migrant students and refugees, contributing to dropout rates [108, 121–124]. Behavioral problems such as disruptive behavior are also linked to dropout for first- and second-generation migrant students [125]. Conversely, factors such as self-efficacy beliefs contribute to academic success for first-generation migrant students [100, 126]. Other studies examine how integrated self-concepts—such as emotional intelligence, ego-identity, and resilience—along with positive attitudes, motivation, cognitive abilities, and behavioral engagement contribute to the academic success of first- and second-generation migrant students [112, 126–136]. Similarly, the concept of “encapsulated resilience of normative longing” underscores refugee students’ inner strength and adaptability, ultimately enhancing their academic performance [113]. High aspiration can protect against vulnerabilities and improve the academic achievement of first- and second-migrant generations [112, 131], while religious faith can protect against academic underachievement for first-migrant generations [126].

Individual factors such as gender and age also impact academic achievement and ESL. Being male is consistently linked to lower academic achievement and higher ESL rates [101, 115, 118, 121, 123, 127, 132, 137, 138]. This holds for first- and second-generation migrants and refugees. Furthermore, Fierro et al. [139] found that the intersecting male gender with a low SES further exacerbates those academic difficulties. Female students are generally favored in academic achievement, although pregnancy is a vulnerability factor [140]. In terms of intersectionality, female students benefit from attending preschool but are hindered by low parental involvement [141, 142]. In general terms, attending preschool is foundational for subsequent academic success among migrant-background students, correlating positively with math, reading, and science achievement [101, 102, 143, 144]. Higher age at arrival and age at admission are also vulnerability factors for migrant-background students’ and refugees’ academic achievement [95, 110, 123]; however, older age generally improves literacy competence and academic progress [102, 132, 139, 145].

Other factors impacting academic outcomes include poor health for second-generation migrants, foster care placement for refugee students, and feelings of fear of deportation and uncertainty for both migrant generations and refugees [108, 120, 121, 123, 140, 146]. Legal permanency status plays a significant positive role in the academic outcomes of refugee students [123].

4.2.1.2. Family-Derived Factors

Concerning family-derived factors, several findings indicate that family structure and parental conflict with parents significantly affect academic achievement across all migrant-background categories [105, 112, 140, 147–149]. Nonintact families, family separation, and adverse life events, such as parents’ divorce, death, and illness, are correlated with lower school GPAs [105, 148, 149]. Additionally, the number of siblings has a direct proportional effect on academic achievement [135, 138]. Conversely, positive relationships with parents due to positive parenting and family cohesion contribute to positive academic trajectories [135, 139, 150–152]. Ambrosetti et al. [153] discuss the concept of family subjective well-being, which includes the emotional and psychological state of family members, quality of relationships, and level of support, enhancing academic outcomes for both generations of migrant-background students.

Low SES hinders the academic achievement of first- and second-generation migrant children [95, 99, 118, 137, 154, 155], with legal and economic uncertainty positively affecting dropout rates of first-generation migrant students [147]. Elevated SES, on the other hand, correlates positively with academic achievement [101, 106, 107, 110–112, 114, 115, 117, 121, 127, 128, 132, 135, 140, 146, 153, 156, 157]. High family background, including parental education, effort, expectation, and intellectual discussions, has a direct positive relation with academic achievement [101, 106, 107, 110–112, 114, 115, 117, 121, 127, 128, 132, 135, 140, 146, 153, 156, 157].

Parental academic involvement and support are crucial for academic achievement in both migrant generations, with higher levels linked to better academic outcomes and lower levels to poorer performance [126, 127, 131, 135, 138, 140, 154, 158–160]. A crucial element for the involvement and support of the family is the knowledge of the educational system since a limited family knowledge of the host country’s educational system correlates negatively with academic success [105]. Excessive parental control, however, negatively affects the academic achievement of those students [131]. Martinez-Taboada et al. [134] highlight how home–school cultural dissonance contributes to poorer academic performance among first-generation migrant students. Acting as brokers in high-stakes contexts, such as language mediators in official settings, negatively impacts academic achievement for both migrant-background generations [150]. Parental educational expectations, integration, and positive social model are positively related to academic achievements among first- and second-generation migrant students [104, 130, 131, 153, 154, 161, 162].

4.2.1.3. Relationships With Peers and Teachers

Perceived discrimination, including stereotype threat and awareness of negative stereotypes about one’s ethnic group, significantly impacts the well-being and academic performance of both first- and second-generation migrant students [103, 104, 120, 126, 133, 134, 139, 153, 158]. Conversely, awareness of societal discrimination is sometimes linked to higher educational attainment [152].

Negative interactions, such as conflict with teachers and peer deviancy, are associated with lower academic achievement and higher dropout rates among migrant-background students [100, 121]. In contrast, positive relationships with peers and teachers improve literacy progress and overall academic success across migrant-background student categories [95, 100, 102, 108, 114, 125, 127, 139, 145, 153, 157, 161, 163–165]. Furthermore, social support from teachers and peers is crucial in increasing the academic achievement of first- and second-generation migrant students [127].

4.2.2. A Meso-/Exosystem Analysis

Regarding meso-/exosystem factor analysis, Borgonovi and Ferrara [95], Pivovarova and Powers [107], and Peguero et al. [125] identify that school poverty, larger school sizes, and urban locations are linked to higher ESL rates among both migrant-background generations. Additionally, class size influences academic achievement, with larger classes negatively affecting migrant-background students’ performance, while smaller classes benefit them [107].

Schools’ ethnic composition and a high proportion of nonnative speakers in classrooms are also negatively associated with academic achievement for both migrant-background generations [96, 111, 158]. Similarly, Kunz [114] found that segregation and clustering of low-performing students correlate with lower academic achievement for second-generation migrant students.

Results regarding school type are mixed. Private and Catholic schools positively impact math and science competencies [101, 143], whereas ultra-Orthodox schools are associated with lower academic achievement for both first- and second-generation migrants in Israel [138]. However, pertaining to religious affiliations positively influence the social and cultural capital of refugee children, thereby enhancing their academic achievement [166]. School resources, such as second language acquisition support, curriculum flexibility, and inclusive practices, are directly proportional to academic achievement for both migrant-background generations [97, 114, 156, 159].

A supportive and safe school climate is linked to better academic achievement among first- and second-generation migrant students [107, 126], while an unsafe and conflictive environment negatively impacts academic performance [104, 146, 159]. Lastly, early tracking systems are associated with lower academic achievement for both migrant-background generations [95, 106].

Concerning teachers’ characteristics, studies have found that teacher bias, stereotyping, and prejudice toward migrant-background students have a detrimental effect on their academic achievement [104, 146, 159]. Teachers’ work overload also negatively impacts refugee students’ academic outcomes [108]. Conversely, teacher availability and qualifications positively affect academic achievement [107].

Other important factors include school mobility, which negatively affects academic achievement due to frequent school changes for all migrant-background generations [140]. Finally, residing in nonmetropolitan areas negatively influences academic achievement for all migrant-background categories [101], while positive community factors significantly shape academic success. First-generation migrant students benefit from community belonging and a supportive school climate [105], while community safety is linked to literacy and numeracy achievements, with working memory identified as a mediating factor, according to Kim et al. [119].

5. Discussion

This systematic review is aimed at identifying the determinants associated with migrant-background children and youth’s vulnerability to academic underachievement and ESL as highlighted in the literature. Using Bronfenbrenner’s ecological approach, we have categorized these factors into micro-, meso-/exo-, and macrosystemic levels. The review reveals a focus on microlevel factors and a near absence of macrolevel determinants in the literature analyzed. The only macrolevel determinants identified are inconsistent protective policies and increased immigration enforcement, which negatively affect the academic achievement of second-generation migrant students [104, 147], as well as residing in new immigration countries, which poses significant challenges for both first- and second-generation migrant students [97]. This gap hinders a comprehensive ecological understanding of the vulnerability factors influencing academic achievement among migrant students, as individuals and groups are embedded within broader systems of sociopolitical hierarchies and dynamics, subsequently reproduced at the local level and within interpersonal relationships [30]. Therefore, the complex dynamics at play remain overlooked without a structural perspective on educational disadvantages.

A notable finding across the results is that 58% of the studies focus on secondary school levels, indicating that the vulnerability determinants identified affect especially adolescent students from migrant backgrounds. According to the World Health Organization [167], adolescence is defined as a period between 10 and 19 years old, a stage marked by critical developmental transitions. This aligns with Alsaker and Kroger [168], who regard adolescence as a particularly vulnerable period characterized by psychological changes, shifts in self-concept, and evolving relationships with peers and parents, factors that are especially pronounced among migrant-background youth [169]. Therefore, the vulnerability determinants should be interpreted within the context of these developmental dynamics.

The micro- and meso-/exolevel vulnerability determinants can be categorized following Brown et al. [39] and Bozdag [57] vulnerability subdimensions.

Situational vulnerability factors include spatial, sociocultural, and sociopolitical elements. Language proficiency deficits and discrimination hinder communication and integration, while sociopolitical aspects, like foster care conditions for unaccompanied minors or fear of deportation for migrant students without distinctions, affect educational trajectories. Conversely, strong language skills and legal stability can improve academic outcomes for migrant youth. These findings partially align with Rangvid [170], who identified language barriers as a key factor explaining the academic achievement gap between native and migrant-background students in a study based on PISA 2006 data. Notably, this study was conducted prior to 2015 and did not account for vulnerability factors directly associated with the migration process.

Social/environmental vulnerability encompasses broader, intersectional aspects, such as SES, family dynamics, and school relationships. Negative family interactions, low parental education, and lack of academic support adversely impact academic performance, while cohesive family structure, high SES, and supportive school environments mitigate these effects. Positive role models and high parental expectations benefit first-generation migrants, and preschool attendance improves outcomes for both first- and second-generation students. These findings reaffirm the importance of social and institutional contexts in shaping educational experiences. Gender also influences ESL rates, with male students showing consistently higher dropout rates than female students [101, 138], while early pregnancy poses specific educational risks for female students [140]. Notably, this review reconceptualizes such patterns as manifestation of social/environmental vulnerability, rather than outcomes of biologically rooted or “innate” traits. Contrary to essentialist perspectives that treat gender as a biologically rooted vulnerability (particularly in childhood and adolescence) [171, 172], this review aligns with Luna’s [173] interpretation of vulnerability as context-dependent. From this view, it is not gender per se, but socially constructed roles, expectations, and inequalities associated with gender that contribute to educational disadvantage. These findings are consistent with previous reviews, including those by Graham et al. [14], Maehler et al. [11], Radhouane [12], which emphasize the importance of proximal factors, such as gender, age, family composition, SES, and students’ attitudes, as well as intermediate factors, including neighborhood and school characteristics and peer and teacher support. However, unlike the current systematic review, these studies did not address macrolevel factors and focused on specific migrant categories, thus narrowing their scope. Graham et al. [14] align with the present review in highlighting meso-/exosystemic factors such as the importance of teachers’ ability to understand and appreciate students’ cultural heritage without resorting to stereotypes. Moreover, our review aligns with Graham et al.’s one by identifying a predominance of microlevel factors and a scarcity of macrolevel factors.

The results also underscore the need to consider the intersection of gender with other vulnerability determinants, such as low SES. This aligns with Keller et al. [174], who highlight that the intersection of low SES, gender, and migrant background significantly hinders academic achievement. Further, gender-related vulnerability is context-dependent: Male students often face academic difficulties due to social acceptance issues, prejudice, and stigmatization [175, 176], but female students can be penalized by other types of vulnerability factors, such as premature pregnancy among adolescents and low parental support.

This systematic review makes several key contributions to the literature. First, it provides an update to Graham et al.’s [14] findings on the academic challenges faced by migrant-background students by incorporating data from studies published between 2015 and 2023. Second, it applies Bronfenbrenner’s ecological framework, utilizing all three systemic levels, which offers a holistic perspective on the vulnerability factors linked to educational disadvantages for migrant-background students. Third, it broadens the focus to include all migrant populations, allowing for a comprehensive examination of the phenomenon. Furthermore, the inclusion of the vulnerability dimension frames these factors into a coherent conceptual framework. Lastly, the review underscores the specific vulnerabilities of migrant-background students during critical developmental stages, such as adolescence, highlighting the urgent need to address contextual and structural barriers in the educational environment, with particular attention to marginalized youth.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

The findings presented in this systematic review should be interpreted while considering its specific limitations. Firstly, the inclusion criteria were restricted to articles published in English, which may have excluded valuable research published in other languages. Secondly, while we selected Scopus for its extensive coverage of scientific journals and high-quality bibliometric data, making it the largest and most relevant database for peer-reviewed research in the social sciences [177, 178], relying solely on this database may have led to the exclusion of relevant studies indexed in other databases. Thirdly, as a literature review, its conclusions are inherently limited by the scope and quality of existing literature. Lastly, although the terms used for the syntaxis have been the result of extensive debates, they have influenced the scope and comprehensiveness of this systematic review. The terms chosen intrinsically constrain the study due to potential variations in terminology. Future research could address these limitations by incorporating studies in multiple languages, utilizing additional databases for article retrieval and conducting empirical investigations and meta-analysis to validate this review’s findings, particularly if addressing or considering the literature biases identified in this systematic review.

7. Conclusion

This systematic review has identified and systematized the determinants of vulnerability among students with migrant backgrounds according to the literature that explores their impact on educational achievement and ESL.

The study reveals a predominant focus of this literature on quantitative methodologies, with a scarcity of qualitative and mixed method studies. Moreover, our review identified a gap in addressing macrolevel vulnerability factors, underscoring the need for a deeper exploration of how structural factors influence the educational outcomes of migrant students. Building upon established frameworks, we categorized the identified determinants of vulnerability into three dimensions: innate, situational, and social/environmental. Integrating these various determinants is important to offer a nuanced and comprehensive understanding of migrant students’ experiences. The review has also revealed a moderate consideration of intersectionality in understanding these vulnerabilities. The literature emphasizes the critical role of protective factors, such as emotional resilience and legal permanency status, in mitigating these vulnerabilities and promoting academic success among migrant-background students.

This review showcases how, by employing the concept of vulnerability analytically rather than stigmatically—considering its multidimensional and multilevel nuances, including macrolevel influences—scholars as well as policymakers and educators can better identify, understand, and address the educational needs of migrant students and mitigate the intergenerational transmission of social exclusion.

Disclosure

This review was not registered in any public database, and a formal protocol was not prepared for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This article has been elaborated within the research project LET′S CARE: Building Safe and Caring Schools to Foster Educational Inclusion and School Achievement, funded by the European Commission under the Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Programme, Contract No: 101059425.

Acknowledgments

We express our heartfelt gratitude to all the researchers at Comillas Pontifical University who are involved in the project “Let us Care” and Bergen University for valuable insights.

Endnotes

1Universal vulnerability explores the interconnected nature of human existence, challenging the notions of autonomy and independence [45]. Vulnerability related to risk delves into “the potential to suffer harm or loss” and is closely related to an individual’s capacity to anticipate a hazard, cope with it, resist it, and recover from its impact [46] and presents connections to institutional power and regulations [47–50].

2At first, we contemplated using the WoS database as well, but ultimately, we opted to exclusively proceed with the Scopus database due to its comprehensive coverage and expansion of WoS’ content.

3PRISMA stands for “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses.” Official website: http://www.prisma-statement.org/.

4Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at http://www.covidence.org

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supporting information of this article.