“Love, You Need to Give Your Child Love”: Mothers’ Perceptions of Nurturing Care for Young Children in South Africa

Abstract

Background: Nurturing care of young children is aimed at promoting lifelong, intergenerational health and well-being, as well as social and economic benefits. This study is aimed at qualitatively exploring maternal perceptions related to nurturing care, their access to information and support for caregiving, the home and community environments and practices, and how caregivers promote infants’ health and well-being in Soweto, South Africa.

Methods: The study employed a sequential, two-stage process. First, three focus group discussions were conducted with a total of 19 mothers of children aged 0–24 months, which then informed 12 in-depth interviews (four women from each focus group discussion). Focus group discussions and interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim and data were analysed using thematic analysis.

Results: The health and well-being of infants were generally described in relation to their feeding and growth and how physically active they were. The need for pregnancy and caregiving information, accompanied by opportunities to discuss this with a health care worker or other women, was highlighted by participants in this study. Potentially obesogenic and non-responsive infant and young child feeding practices were commonly reported by mothers. Responsive caregiving was described as taking care of children’s physical needs, providing them with love, and playing with them. Female matriarchs were particularly influential in providing caregiving advice and support for mothers. Naturally occurring interactions, such as talking and singing, were commonly reported practices to promote children’s development in the home. Safety concerns were ubiquitous and limited children’s play and exploration outside the home.

Conclusions: This is one of few studies to explore caregivers’ perceptions of nurturing care in the South African context and the first to focus specifically on the first 1000 days. Thus, the study findings can contribute to strengthening initiatives to support caregivers to provide nurturing care for young children in South Africa and other similar contexts. Findings point to the need for better targeted information and support for mothers and other caregivers around nurturing care, especially elements related to infant and young child feeding (including responsive feeding), responsive care, early learning, and how to address safety in the home. There is also a gap in the provision of appropriate information and opportunities to engage with peers and health care workers around issues pertinent to pregnant women within current services. These deficiencies can be addressed through strengthening existing services, leveraging current platforms of care and support for pregnant women and young children, particularly through the health system.

1. Introduction

The 2017 Lancet series on early childhood development (ECD) emphasised the importance of nurturing care, particularly for children under the age of three [1]. Nurturing care—which encompasses good health and nutrition, responsive caregiving, opportunities for early learning, and being cared for in safe and secure environments—is aimed at promoting lifelong and intergenerational health, as well as social and economic benefits [2]. Nurturing care of young children starts in the home and is provided first and foremost by a child’s primary caregivers. This was further emphasised by the 2018 Nurturing Care Framework [3], which also highlighted the important role of health systems in promoting and supporting nurturing care for young children, given the multiple, frequent contacts with pregnant women and children during this time.

In South Africa, these nurturing care commitments are articulated in the 2015 National Integrated ECD Policy [4] and the National Development Plan 2030 [5], which highlights the importance of the first 1000 days and its impact on child school performance and human development. The health sector is recognized through the specific leadership responsibilities assigned to the sector, especially with respect to the period from conception to age two [4]. Two key developments by the National Department of Health have been the redesign of the national child health record, Road to Health Book, which was released in 2018, and the accompanying under-5 Side-by-Side campaign to promote and support nurturing care [6]. This campaign focuses on fostering the supportive relationship between child and caregiver, as well as the relationship with practitioners, including health care workers, who help and advise the caregiver. Side-by-Side seeks to convey that raising a child is a partnership, reminding everyone that “it takes a village to raise a child.” It emphasises the experience of child rearing as a journey shared by caregivers, their children, and everyone who helps and supports them. The Road to Health Book, which is at the centre of the campaign, serves to provide structure to children’s and caregivers’ interactions with health workers through its content, which is organized around five “knowledge pillars” or themes: nutrition, love, play and talk, protection, health care, and extra care [6].

In order to expand and strengthen these national approaches to promoting nurturing care, especially for the youngest children, more information and understanding are required about current caregiving perceptions and contextual practices that promote nurturing care in the South African context. Thus, the aim of this study was to use a qualitative approach to explore maternal perceptions related to nurturing care, as well as mothers’ access to information and support for caregiving, their home and community environments and practices, and how young children’s health and well-being are being promoted.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Status of Nurturing Care of Young Children in South Africa

Persistent inequality alongside rising poverty and unemployment in South Africa, compromises parents’ and caregivers’ ability to provide nurturing care for young children, thereby impacting on their health, development, and well-being in the short and long term [7].

Despite national efforts to support nurturing care of young children, more than half of 4–5-year-olds attending early learning programmes in South Africa are not developmentally on track [8]. The 2022 Thrive by Five Index Report [8] showed that, of the 4–5-year-olds assessed, less than half (48%) were on track in their gross motor development, 30% were on track in their fine motor and visual motor integration, and just over half (55%) were performing as expected for their age in emergent literacy and language skills. In a South African study conducted with 3–5-year-olds attending early learning programmes [9], 40% of caregivers reported that they did not have any pictures or children’s books in the home and significant proportions never engaged in activities, such as reading, telling stories, or singing to children; having more books and toys at home was positively associated with fine motor coordination, visual motor integration, and cognition and executive functioning. More than two-thirds of the sample reported having 2 h or less during the week and weekends to spend with their child [9].

A recent statistical overview of South Africa’s youngest children estimated that 1 in every 25 children dies before their fifth birthday. Of those that survive, 71% of children live in households that do not have sufficient income to meet their basic needs, and over 25% of children under 5 years are stunted—a sign of chronic malnutrition that compromises physical growth and brain development [10]. Worryingly, the same analysis showed an almost 70% increase in overweight and obesity amongst this age group from 2016 to 2022, with nearly a quarter of children in this age group classified as overweight or obese [10].

The most recent South African Demographic and Health Survey [11] data highlighted that less than a third (32%) of infants younger than 6 months of age are exclusively breastfed and that only 23% of children aged 6–23 months met the criteria for a minimum acceptable diet.

South African children are at high risk of exposure and experience of violence in their homes and communities [12–15]. Evidence from the Birth to Twenty birth cohort study [14] showed that exposure to violence is pervasive, and it starts early—nearly half of the preschool-age children in the sample had experienced some form of violence, mostly in the form of physical punishment by their parents. The study also showed that there is an increase in children who were victims of violence becoming perpetrators of violence later in childhood and perpetuating these behaviours with their offspring [14].

These worrying statistics emphasise the need for appropriate information, support, and services for parents and caregivers to ensure that infants and young children are cared for appropriately and protected from harm.

2.2. Caregiver Perceptions of Child Development and Care

Whilst there is general agreement on the importance of ECD, previous studies have shown that a critical barrier to improving the development of the youngest children is a tendency to “age up.” The public, including caregivers of young children, perceive that learning only starts around the time when children attend structured early learning programmes, such as preschools, and that adolescence is the best time to influence their development [16, 17].

There is limited local and regional evidence on perceptions of child development and how to promote it in the home. There have been previous studies conducted that explore caregiver perceptions and practices to promote child development and care between birth and 2 years in sub-Saharan Africa. Studies conducted in Malawi [18] and Burkina Faso [19] reported barriers to caregivers providing nurturing care—such as limited time, competing demands, the involvement of other family members in care (such as fathers), financial barriers, and the need for relevant culturally appropriate information and support. Similarly, in a previous South African study [16], parents expressed that, other than a child’s parents, grandmothers were the most appropriate caregivers.

Previous South African research indicates that learning opportunities provided in the home for young children are scarce, and barriers such as poverty and the lack of caregivers’ time (to spend with their child) and safe spaces make it difficult for caregivers to incorporate activities to promote child development into daily life [9, 17, 20, 21].

Previous local studies exploring caregiver perceptions of early childcare have mainly focused on older children [22–25] or have focused on specific domains of nurturing care, such as feeding and growth [26, 27] or play and development [20], with little knowledge about how to support parents and caregivers to provide nurturing care during the first 1000 days.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

This qualitative study employed a sequential, two-stage process, namely, focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted, which then informed in-depth interviews (IDIs) to further explore the research questions and gain a deeper understanding of topics discussed in the FGDs. The study was conducted between February and November 2018. All FGDs and IDIs were held at the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC)/Wits Developmental Pathways to Health Research Unit, in Soweto, Johannesburg, South Africa.

3.2. Participants

Participants, mothers of children aged 0–24 months, were purposively recruited using a sample of mother–child pairs from an existing observational study being conducted at DPHRU. Twenty-eight mothers were randomly selected and invited to participate, with 19 mothers agreeing to take part in one of three FGDs at the study site. Participants were included if they were residents in the greater Soweto area, aged 18 years or older, were able to participate in a FGD either in English or in a vernacular language, and provided informed consent (including agreeing to being followed up for a subsequent interview). From those who had participated in the FGDs, women were approached to participate in an IDI, based on their level of participation in the FGDs; with an aim of having an equal number of participants from each FGD. The number of IDIs per child’s age group was determined according to when data saturation was reached across all dimensions identified during the exploratory FGD phase.

The Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of the University of the Witwatersrand provided ethical approval for the study (M171129 and M170707). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants for both the FGDs and the IDIs as applicable, as well as for audio recording of discussions.

3.3. Data Collection Procedures

FGDs and IDIs were conducted at the study site by a member of the research team and/or by multilingual, qualitatively trained, and experienced graduate-level female research staff from Soweto. The research team includes postdoctoral researchers in the fields of maternal and child health, nutrition, ECD, physical activity, and anthropology. Three FGDs were conducted, and participants were grouped according to the age of their child: 0–6 months; 7–14 months; and 15–24 months. FGDs and IDIs were mainly conducted in English, but participants were able to converse in vernacular languages. Each FGD and IDI was conducted by two facilitators: one to lead the discussion or interview and another to act as an observer and document comprehensive written field notes and observations to supplement the audio files. The FGDs lasted between 60 and 120 min, and the IDIs took between 60 and 90 min.

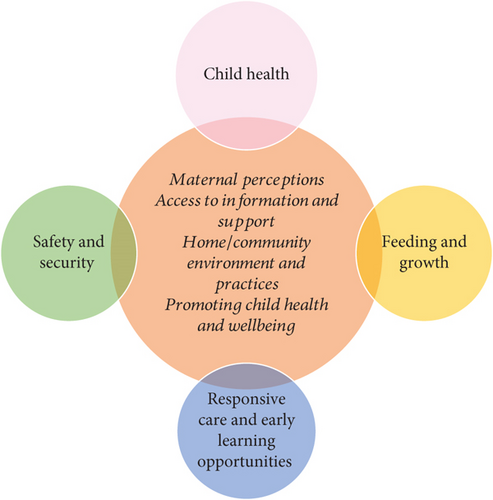

Prior to the FGD, a short sociodemographic questionnaire was completed by each participant, with the assistance of a trained member of the research staff. The study topic guides (for FGDs and IDIs) were informed by the framework presented in Figure 1, which was based on the Nurturing Care Framework for ECD [3] and included an exploration of the key interrelated components of nurturing care: child health, feeding and growth, safety and security, responsive caregiving, and opportunities for early learning [2]. Questions explored maternal perceptions related to nurturing care, their access to information and support for childcare, the home and community environments and practices, and how young children’s health and well-being are promoted in the home.

IDIs were conducted to gain a deeper understanding of the discussion topics raised during the FGDs and to further explore gaps identified during the FGD analysis. The themes that emerged from the FGD analysis were used to develop and refine the IDI guide. Accordingly, a semistructured interview guide was used to promote open dialogue around the topics and allow for exploration into any new discussion topics. FGDs and IDIs were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, with translation where required.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data were analysed using thematic analysis [28, 29] in Dedoose 8.2.31 software (SCRC Co., Manhattan Beach, California, United States), with a combination of deductive (drawing on study framework) and inductive approaches. Each FGD transcript was analysed by one of three researchers, through a series of steps: familiarization with the data (including written notes); coding the data; identifying patterns; and generating, reviewing, and naming themes. Researchers’ cross-checked transcripts and coding frameworks to ensure that we were coding similarly; thereafter, meetings were held to compare, contrast, and discuss emerging themes.

A fourth, independent researcher then assessed the quality and validity of the coded data and differences, and the issues raised were discussed and agreed upon collectively. The fourth researcher cross-checked and collated themes that were common and unique across all the transcripts to develop a FGD data codebook. Thereafter, data analysis and interpretation of themes and the codebook were reviewed, refined (until no new themes emerged), and finalised as a group. This codebook was also used as a basis for coding the IDIs.

All four researchers, using a thematic grouping approach, independently analysed the IDIs according to the identified focus areas. Where the FGD codebook did not include sufficiently detailed themes for a particular research area, further subthemes/themes were identified and added. The themes and subthemes were analysed, compared, and agreed upon amongst the researchers. Aspects related to feeding and growth, as well as play and physical activity, have been reported in more detail in prior publications on this work [20, 26, 27]. Thus, in relation to these components of nurturing care, we will present findings that are more closely related to responsive care, including responsive feeding and early learning, rather than more general descriptions of findings in these domains.

4. Results

Nineteen mothers consented to participate in the FGDs, and 12 mothers agreed to an IDI (four from each FGD). The age of mothers in the study was (mean ± SD) 27 ± 6 years, ranging from 21 to 38 years. All participants had completed Grade 12 or attended at least some secondary school, and the majority (n = 15) were unemployed. Most mothers (n = 13) had more than one child, and less than half were married or living with a partner.

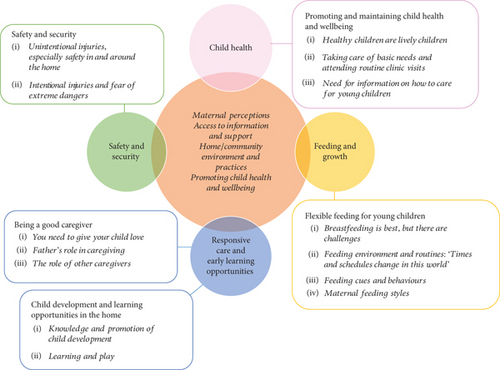

Five main themes emerged from the FGDs and IDIs, and the results are presented accordingly: (1) promoting and maintaining child health and well-being, (2) feeding young children, (3) being a good caregiver, (4) child development and learning opportunities in the home, and (5) safety and security.

4.1. Promoting and Maintaining Child Health and Well-Being

4.1.1. Healthy Children Are Lively Children

Children’s health was generally described in relation to feeding and growth or body size, and how physically active or inactive they were. A poor appetite was considered a sign of illness, and some mothers perceived children who were too big or heavy as unhealthy as it affected their ability to move around or play and could interfere with their general health. However, others expressed that a “chubby” baby was generally considered desirable and a sign of a happy and healthy baby.

To be able to make sure your child is eating and if they are not then to be aware that they are not and why they are not…to understand if they do not eat, then they are sick. (FGD; mothers of children aged 15–24 months)

I think the baby is healthy because in most cases if the baby is fat or they grow too much it means they are “fresh” like they eat well… Uhm (sigh) in some cases maybe the baby is fat or chubby, happy like she just looks normal. (IDI; mother of a 17-month-old)

A lot of the times, the child is too heavy for himself, when he walks and even when they play, even when they are young they have short breath even despite being so young, all because of the fat, because he’s overweight. (IDI; mother of an 8-month-old)

A physically active child was regarded as a healthy child and described as “busy” and “lively.” In contrast, a child who was considered “quiet” or “not playing” was thought to be an unhealthy child. Mothers also mentioned other caregiving aspects that contribute to keeping children healthy, such as the importance of having attentive and loving caregivers or that a “happy” child was a sign of health. Play was perceived as important and generally regarded as both a reflection or marker of a healthy child and an enabler of a child’s general health and well-being. Socialising with other children was viewed as important for a child’s healthy development.

He has to be busy, like if he’s playing, he’s busy, I see that he’s healthy. (FGD; mothers of children aged 7–14 months)

When mine does not play I worry, I think he feels there’s something wrong in his body. (IDI; mother of a 13-month-old)

We play games. It’s like exercise. Like throwing balloons, throwing a balloon, like uh, I run after him, and I play ‘tag you’re it’… ja. (IDI; mother of a 2-month-old)

I think that it’s better if the baby plays with other kids, even if it’s for a few hours or something so that he or she may know or connect with other people. It does not matter if you are unemployed or employed, but the children need to play with other kids so they connect, so that she must not be scared to play with others because some kids grow up being shy and alone. (FGD; mothers of infants aged 0–6 months)

4.1.2. Taking Care of Basic Needs and Attending Routine Clinic Visits

In addition to basic caregiving and feeding practices, regular attendance at routine clinic visits (for immunisation, growth monitoring, etc.) was considered important for maintaining children’s health and protecting them against illness.

Okay, healthcare is all about the child’s health; in terms of taking them to the clinic, and the food they eat. (FGD; mothers of children aged 7–14 months)

Your child must be happy at all times and also taking your child for regular visits at the clinic. Some people claim their kids do not fall ill and they have never set foot inside the clinic after giving birth, but then you will not be able to help your baby when she’s ill because missed clinic visits cannot be rectified once baby is sick. You cannot give a 12-year-old an injection that she needed to get at 1 years old, it means you have not been looking after your child. (FGD; mothers of children aged 15–24 months).

4.1.3. Need for Information on how to Care for Young Children

Health facilities (clinics) and health professionals (such as nurses) were regarded as important sources of information. However, the advice and support received from family and friends, particularly grandmothers and great-grandmothers, were considered as most important. Some mothers reported that they would rather follow the advice offered by family matriarchs, as these were often the people who assisted and supported them with childcare.

Mothers also referred to the information in clinics and the Road to Health Book as being helpful but felt that they needed health workers to explain the information to them, particularly regarding signs of illness or injury, and child development milestones and activities. Easily accessible pregnancy-related information was also an area that mothers felt needed improvement. Speaking to other mothers, searching the Internet (Google), or using online or social media parenting groups when having concerns were frequently mentioned as sources of information.

[I get information] on the development of my baby from the book, her book. Some from my mother, some from the clinic walls…, a lot of the information is plastered on the walls at the clinic, so you read it when you walk past. The nurses, if you took the baby for a vaccine, they do that and give you the next date, you must just read the stuff for yourself. (IDI; mother of a 17-month-old)

I only ask my mom for anything if I do not know. My mom gets upset and takes offense when I do not take her advice. She says if my child gets sick, I must go to the clinic and just live there with my child. (FGD; mothers of infants aged 0–6 months)

I want to be empowered; I want to know more about how I can help my baby because my mom will not always be around…Tips on what to do when the baby is sick, and the clinic is too far (IDI; mother of a 17-month-old)

I read, like online. Like, these group chats, and… Mommyhood (sic). There’s one that I’m on, like the advice and stuff it helps. Ja, it is mommies giving each other advice (FGD1; mothers of infants aged 0–6 months)

4.2. Flexible Feeding for Young Children

4.2.1. Breastfeeding Is Best, But There Are Challenges

Mothers generally regarded breastfeeding as the best feeding choice for young infants, based on the information provided at the health facilities and the affordability of breastmilk. However, issues were raised regarding the challenges of breastfeeding and maternal and/or family concerns about the adequacy of exclusively breastfeeding young infants. Breastfeeding challenges related to anxieties about producing enough milk and the difficulties of breastfeeding in public spaces were raised.

I think breastfeeding is better than giving your child formula from a bottle. Breastfeeding is good, yes, sometimes you cannot afford to buy milk because you do not have money, so then what will the child eat in that instance? So, the breast milk is better because you do not have to buy it. (FGD; mothers of infants aged 0–6 months)

And we are all different, some parents have little breast milk, like I cannot fill up one bottle, I have to make more milk and fill up two bottles or my child will not be full. (FGD; mothers of children aged 15–24 months)

And some mothers make life difficult for ourselves; we dress in clothes that will make it hard to breastfeed. You’ll find your child crying and you ignore them because you do not know what to do, you’ll end up stripping your clothes. (FGD; mothers of infants aged 0–6 months)

Mothers reported that mixed feeding (breast and formula feeding) as well as the early introduction of complementary feeding was commonly practised in their communities. Infants are frequently fed solids in the first weeks or months after birth, with maize or sorghum-based porridges being a common first food. This is given either in a bottle (in a more liquid form) or fed to the infant with a bowl and spoon. Water and tea are also given to young infants. Mothers reported that early feeding of solids is introduced in response to anxieties about exclusive breastfeeding not being enough to satisfy hunger in young infants, to optimise their child’s growth (a “chubby” baby signifies health), to help infants sleep better (particularly during the night), and to help soothe infants who were regarded as “fussy.”

She [her baby] arrived at home and mom said give her food because she’s hungry. (FGD; mothers of children aged 7–14 months)

Yes, you must give him, like porridge…I gave him at two months…he was problematic, he was breastfeeding a lot. Ja, he would not sleep at night, he was difficult to put to sleep…sometimes a little food in the tummy is necessary. (IDI; mother of a 12-month-old boy)

If my child was 6 months without eating solids, he’d be skin and bones only not chubby as he is now. (FGD; mothers of infants aged 0–6 months)

4.2.2. Feeding Environment and Routines: “Times and Schedules Change in This World”

Feeding happened when and where was most appropriate in the household; shared family mealtimes were not the norm. Feeding young children in front of the television (TV) and the child eating separately from the rest of the family were commonly reported practices. There was general awareness and agreement on the frequency of meals that young children should consume, and although all mothers did not strictly schedule mealtimes, there was some consistency as to the general times when children ate meals. However, the use of set mealtimes (“schedules”) or routines for feeding (e.g., a standard place where the baby is fed) was not regularly practiced amongst the participants. The main explanation provided by some mothers highlighted the importance for children to be able to adapt to changes in routines and that set mealtimes could cause difficulties if the child was not at home or was not fed “on time.” Mothers reported that they sometimes had to feed their children whilst they are in public transport or experiencing delays in their usual routines; thus, it was deemed important that children understand that things do not always go as expected.

We do not sit at the table. He eats and runs around…(or) He sits and watch TV, by the sofa, he eats there. (IDI; mother of a 1-month-old boy)

… Let us say you normally give her porridge at 12 pm, now you are in a taxi and have cold porridge and she wants the hot porridge that you usually give her at 12 pm not the cold one, she’ll be fussy the entire journey. (FGD; mothers of children aged 7–14 months)

Like if they normally eat at 1 pm and one day the food that you give her is not there at 1 pm, you need to change the feeding times because things happen, so you need to teach your child that times and schedules change in this world we live in, and things do not happen at the same time every day; yes you’ll give them what they need but not at the same time every day necessarily. (FGD; mothers of infants aged 0–6 months)

4.2.3. Feeding Cues and Behaviours

Sometimes, feeding times were determined by the caregiver, when the child indicated signs of hunger (such as crying), or when older children said that they would like to eat. Some mothers reported observing the child’s behavioural cues as key to deciding whether to feed them or if the child is showing signs of satiety. Others commented that they would note the time or the amount the child ate or physical signs, such as a “big tummy,” to indicate whether the child was full.

She does not cry but fakes as if she’s crying and she becomes restless and moving around, but when she reaches for the breast and of course milk does not satiate her so, I know then as well to feed her solids. (FGD; mothers of children aged 7–14 months)

I listen to him; I know him I can feel his stomach and I can see his food on the plate that he must be full now. (IDI; mother of an 8-month-old)

I just guess (that she is hungry), I do not wait for her to cry or anything, I just make food for her especially if I’ve already made food, I give her, and she eats. (IDI; mother of a 17-month-old)

For as long as he stops opening his mouth, because he’s big now, when he does not want to eat, he says no, he either throws the food out or distracts you. If he wants to eat, he will open his mouth and if he does not want to, he shows it. (IDI; mother of a 23-month-old)

4.2.4. Maternal Feeding Styles

A mixture of parent-led and child-led feeding was reported, ranging from coercive, parent-controlled practices using strategies such as pressurizing the child to eat, restrictions (withholding food or limiting choice), and emotional feeding (such as to comfort or soothe the child) to more permissive, child-controlled practices, such as eating in a disorganized or unstructured feeding environment (e.g., eating whilst watching TV) and providing foods based on child preference. Food refusal was a frequent complaint, with “force feeding” a commonly employed strategy. Some mothers felt that this practice was influenced by how they were fed as children and was passed on by their mothers. However, examples of positive responsive feeding practices, such as allowing the child to feed himself if age-appropriate and reintroducing foods if the child initially refuses, were also mentioned.

Right now, he feeds himself like you give him his plate of food and you put it in front of him and he feeds himself… He plays with his food and makes a mess on the floor. (IDI; mother of an 18-month-old)

[Interviewer]: Okay, so when you say he eats on his own, how does he do it?

[Mother]: He eats uh, like yoghurt and stuff on his own, but then other food he does not… I do not make him eat because he’s picky, he’ll eat one thing and not the other. (IDI; mother of a 2-year-old)

Yoh, she does not like food, like she’s picky on certain days or sometimes, you have to force her. I force her if she has not eaten, and she does not want to eat. I force her, I’ll give her three or four teaspoons if I see that she genuinely does not want to eat. As long as she’s had something. (IDI; mother of a 17-month-old)

4.3. Being a Good Caregiver

4.3.1. “You Need to Give Your Child Love’

Being a good mother or caregiver was described as taking care of children’s basic (or physical) needs, such as making sure that they are not only clean and well-fed but also loved and played with. Some mothers reported that their children respond to their emotional state and that the bond and love between mother and child is unique and cannot be replaced or replicated by other caregivers. The importance of being aware of their child’s behaviours and needs was emphasised by mothers and indicates a “strong” bond between the mother and the baby.

Love, you need to give your child love, and the child will bond with you through the eye contact and the like, so they know that my mother is (FGD; mothers of children aged 7–14 months)

Attention, making sure that she’s playing; if my child is playing, she’s well, if she’s happy she’s well. And then also giving them love, then they’ll be fine; yoh, the love that I have for my child, I cannot describe it but then… Like I give my all, even my whole being, there’s nothing I would not do for my child, if she starts crying, I’m already there. (FGD; mothers of children aged 7–14 months)

…he’s 6 months and he’s already responsive when you talk to him, so ultimately what I want to say also is that you need to love your child, if you do not give your child that love, no one else will. Yes, there may be the dad and siblings and grandmother, but a mother’s love is special. (FGD; mothers of infants aged 0–6 months)

I… I love him, I kiss him, I play with him, I talk to him, and we have conversations you know, ja. (IDI; mother of a 19-month-old)

Even the change in emotions, they register that, because sometimes you’ll find yourself crying and they also cry… They pick up on these changes in emotions, sometimes my child will see me crying and she’ll reach out to me and pull my face close to her because she wants to know what’s going on with me. (FGD; mothers of infants aged 0–6 months)

4.3.2. Father’s Role in Caregiving

Mothers reported fathers’ role in caregiving as providing financial and material support, playing with children, and presenting children with recreational opportunities (such as walks to the park); where cohabiting, fathers shared in some of the caregiving responsibilities (e.g., feeding and bathing). Several mothers indicated that fathers had minimal input in the day-to-day caregiving activities (such as feeding) and needed to consult with them (mothers) regarding parenting decisions.

My partner gets piece jobs… and he does something for the child if he has the money. (IDI; mother of a 23-month-old)

When he’s with his dad…they play with a ball and pass it to each other like volleyball or drive through the neighbourhood and go to the mall. (IDI; mother of an 18-month-old)

Ja, he does [take care of child] too but a lot of the things it’s me because if there’s something he wants to do, he has to run it past me and if I agree then ja we’ll do it. If I do not then no. (IDI; mother of a 17-month-old)

4.3.3. The Role of Other Caregivers

Besides fathers, female family members, especially grandmothers, were particularly influential in caregiving practices and decisions. Some employed mothers used child day care, but this was not always regarded as a positive choice for young children. Several mothers preferred that their children were cared for by family members, such as grandmothers or aunts. There were general concerns about the quality of care that young children receive in group childcare arrangements, such as day care centres or with childminders caring for more than one young child, especially infants, at a time.

On my side, I will leave my baby with someone I trust, not a crèche because there are many children there, so she has to focus on this baby and that one and that one. (FGD; mothers of infants aged 0–6 months)

Yes, some do not have someone to stay with the baby, others are scared of leaving the baby at crèche because some crèches aren’t good. (IDI; mother of a 17-month-old)

4.4. Child Development and Learning Opportunities in the Home

4.4.1. Knowledge and Promotion of Child Development

Mothers reported using certain developmental milestones as markers of “good development,” such as walking, to gauge whether their children were developing appropriately according to what they expected for their age. Hence, mothers felt that activities such as talking and playing with their baby and watching TV, especially cartoons as it was deemed age-appropriate content, helped to promote child development. Watching TV, particularly cartoons or children’s programmes, was more commonly reported and was considered as having educational value for young children.

When a child is first born, they cannot see and then at 3 months they start to see. When you move your hand across their eyes they can see, they play with the curtains when you put them on the bed, things like that. I wanted to see if my child could walk. When he started walking, I knew that he was developing fine, and talking when I would say something, and he repeated it, I could see that my child is fine. (IDI; mother of a 23-month-old)

I’m always with her, we play, sleep and wake up, and sometimes we have nothing to do so we just watch TV, but most of the time it’s cartoons. At least she’s focusing on something, it’s better than just sitting. (IDI; mother of a 17-month-old)

They told us (nurses) during the pregnancy, they say even when they baby is playing in your stomach, you must play with him so he can hear you and know his mother’s voice. (IDI; mother of a 13-month-old)

4.4.2. Learning and Play

Naturally occurring activities, such as talking to and singing to young children, rather than toys were commonly reported ways caregivers promoted children’s development in the home. Providing children with space to explore and run around and having toys available in the home were considered important by mothers; however, this was often dependent on finances and whether mothers felt that it was age appropriate. Few mothers reported that they told stories or read to their children; these activities were regarded as being for older children. Many mothers felt that book reading was appropriate to introduce when children were preschool age, with one indicating that reading books with young children “was only what people on TV did.”

Children were allowed to play outside, but excursions to the park or other recreational spaces were not common practice amongst participants. This was mainly due to safety concerns or deemed as inappropriate for younger children as they would not be able to use the play equipment. When children visited the park, they were mostly taken by their fathers.

I’ll only start buying toys when he’s like 2 years or something and he knows what to do with them. (FGD; mothers of infants aged 0–6 months)

Ja, I do not read to him…I like [singing] songs. Maybe gospel, ja or maybe I put on a DVD, ja. (IDI; mother of a 2-month-old)

[Interviewer]: Do you ever read to him?

[Mother]: No, I do not

[Interviewer]: When do you plan on reading to him?

[Mother]: When he’s a bit smarter, at age 3. (IDI; mother of an 18-month-old)

4.5. Safety and Security

4.5.1. Unintentional Injuries, Especially Safety in and Around the Home

Young children reportedly played mainly indoors or in the backyard of their homes under close adult supervision. Mothers preferred that children play inside the home as they could control the environment and remove any potential dangers to provide a safe play space.

She goes outside for maybe 5 minutes, if she leaves without me seeing her, I fetch her immediately. I prefer that she plays indoors because outside she can pick up funny things and eat them… We put things that can harm her on top, out of her reach where they cannot harm her. (IDI; mother of a 17-month-old)

I make sure that the shutter door is locked so she cannot go outside because it’s not safe outside. (IDI; mother of a 7-month-old)

Home and community safety concerns were significant barriers to children’s ability to play and explore outside the home, even in the backyard or immediate environment of the house. Mothers reported environmental dangers such as ingestion of small objects, children playing around pit toilets, fear of infection from placing objects in their mouths, and young children running into the road and playing with rat poison as potential dangers.

He must not go inside the toilet; he must not go inside the toilet. I make sure that there aren’t any objects that he could eat, there in the yard you know, ja. (IDI; mother of a 19-month-old).

… like on the street where I live, it’s very busy and even the cars drive as though it’s the freeway, so it’s safe if they play inside the yard… Because you know exactly where they are, you will not be stressed about where he is. (IDI; mother of an 8-month-old)

4.5.2. Intentional Injuries and Fear of Extreme Dangers

Child safety in the community was a pervasive concern amongst participants, with fears of kidnapping and intentional harm to young children, especially girls, being a particular worry to mothers, thus limiting children’s ability to play and explore safely and freely in their community and their enjoyment of local recreational opportunities, such as visiting the park.

…the difficulties under which our children are growing up, the help that we need is safe spaces, we are used to our environment but it’s not safe. (IDI; mother of a 2-month-old)

Like when he’s in the yard I think he’s safe and like recently they abduct children, so when he’s in the yard I think it’s safe because you know exactly where they are, you will not be stressed about where he is. (IDI; mother of an 8-month-old)

…my baby does not play outside. It’s not safe, babies get kidnapped out there and when she’s hurt, nobody will say who did it, they’ll all claim that they do not know so it’s easier if she plays where I can see her. (IDI 9; mother of a 17-month-old)

5. Discussion

This study aimed to qualitatively explore maternal perceptions related to nurturing care, mothers access to information and support for caregiving, their home and community environments and practices, and how caregivers promote infants’ health and well-being.

Our findings (Figure 2) showed that the health and well-being of young children were generally described in relation to their feeding and growth and how physically active they were. Potential obesogenic feeding practices, such as early introduction of solid foods, use of porridge-based bottle feeds, and “controlling” feeding styles, were commonly reported by mothers. Mothers spoke about a special bond with their children, which allowed them to understand their children’s needs better than other caregivers. Responsive caregiving was described as taking care of children’s physical needs, providing them with love, and playing with them. Fathers had limited caregiving roles, with female matriarchs being particularly influential, and their advice and support were considered the most important with regard to caregiving. Naturally occurring interactions, such as talking and singing, were the most common practices to promote children’s development in the home. Safety concerns were significant barriers to children’s ability to play and explore outside the home. The demand for pregnancy and caregiving information, accompanied by opportunities to discuss this with a health worker or other women, was highlighted by participants in this study. The need for strengthening communication between health care workers and mothers/caregivers, particularly related to childcare and feeding, has been emphasised in previous studies [30, 31].

Children who ate well or were “chubby” were regarded as healthy, and children who had a poor appetite or were “skinny” were regarded as ill. The aspiration was to have a baby who was “fresh” (normal weight or slightly overweight for their age), as this was an indication of a happy and thriving child. This was also found in prior studies conducted in this setting, exploring health worker and child minder perceptions of preschool children’s body size and growth [24]. Previous research has shown that this may be driven by fear of the social stigma associated with acute malnutrition of young children, suspicion of HIV, the perception of being a “bad mother,” or that the family is struggling [24, 32, 33]. However, this also applied to children who were thought to be overweight or “too large for their age,” as they were perceived as less active compared to their peers. This was not necessarily regarded as a marker of child health or development but rather that these children tended to be “lazier” than their counterparts. According to the 2016 South African Demographic and Health Survey, 13% of children under the age of five were overweight (weight-for-height greater than +2 standard deviations from the reference median) nationally [11]. The latest National Food and Nutrition Security Survey data showed that this figure has increased to 23% in 2021–2023 [34]. Physical activity is a known indicator of health and well-being, and healthy physical activity and lifestyle habits are established early in life [35, 36].

Although most mothers were advised of the benefits of breastfeeding for young infants, many had not exclusively breastfed for the recommended period, with mixed feeding and early introduction of solid foods being commonly reported practices. This was mainly due to the perception that infants were not satiated with breastmilk and needed food and/or breastmilk substitutes to appease their hunger. It may also be related to the general preference emerging from this study’s findings for a “chubby” baby, which is a physical expression of a child’s appetite and good health. This advice was often provided by trusted female members, most commonly grandmothers and other female elders, who appeared to significantly influence caregiving decisions and practices. Fathers had limited caregiving roles, particularly related to feeding, with mothers taking responsibility for most of the parenting decisions. The important role of female matriarchs in caregiving decision-making, including feeding practices, is well documented in the local and global literature. Thus, there is greater recognition of the importance of including partners and family members, particularly female elders, in interventions that are aimed at supporting infant and young child feeding [37–39]. However, despite increasing policy shifts and some efforts to implement more comprehensive approaches to supporting child health and development, most support interventions are routinely applied through the health system (the first and most frequent contact point for pregnant women and young children) [40] and remain focused largely on the individual mother–child dyad.

Mothers frequently reported “controlling” feeding styles, such as pressurizing or “force-feeding” children, or adopting more casual approaches to feeding, such as feeding children in front of the TV. The use of feeding routines was also not common practice amongst participants in this study, neither was using feeding time as an opportunity to encourage communication and interaction between the mother and child. The importance of the family and household environment for children’s healthy growth and development is well recognized; however, most current national-level nutritional interventions focus on children’s diets, with limited consideration of the important influences of the family and caregiving environment [41, 42]. Caregiver–child interactions and dietary patterns and practices are established and can be entrenched early in life [43–45].

Stemming from the responsive parenting literature, it is predicted that responsive feeding practices and interactions promote children’s awareness of their internal hunger and satiety cues, attention and interest in feeding, ability to communicate their needs to their caregiver, and their ability to effectively progress to independent feeding. These practices are characterised by caregivers providing pleasant feeding environments, with minimal distractions that promote interaction, and creating predictable mealtime routines and expectations, with caregivers who respond promptly, appropriately, and consistently to children’s signals and behaviours [42]. Non-responsive feeding practices, such as a lack of reciprocal caregiver–child interaction evidenced in more controlling (e.g., forcing or restricting food intake), laissez-faire feeding styles (e.g., lack of encouragement to feed, uninvolved feeding, or early expectation of independent feeding), or where the child controls the feeding situation (i.e., indulgent feeding style), are associated with feeding difficulties and poor growth (underweight and overweight) [42, 46–48]. Thus, the commonly reported non-responsive feeding practices in our study raise the need for more targeted information and support for caregivers on how to adopt responsive feeding practices.

Caregiver awareness or sensitivity was expressed through reports of a unique bond between a mother and child, which allowed mothers to instinctively know what their babies need. This was spoken about as something that was either present (or not); not as something that could be taught or developed in mothers through support or intervention. Responsive caregiving was described as taking care of children’s physical needs, providing them with love, and playing with them. This concurs with findings from previous studies, where parents perceived young children as developing “naturally”—if a child receives the required love, food, and care, the development will take place [16], thus highlighting that both physical and emotional needs of children should be met to promote early development.

Mothers spoke mainly about ensuring that these needs are met, rather than the interactions that occur between them and their babies during these routine activities. Although talking and singing were frequently reported practices to promote children’s development in the home, few mothers mentioned using feeding or bathing interactions as opportunities to engage in communication and play with their infants.

As in studies conducted in Malawi [18] and Burkina Faso [19], telling stories or reading to children were less frequently mentioned; however, in this study, access to screen time for young children, especially TV, was the norm and often seen as educational. This is consistent with previous research conducted on a similar age group in this context, which reported that caregivers were highly responsive but provided low levels of cognitive stimulation in the home [49]. Similarly, data from the Statistics South Africa’s 2018 ECD report, indicated that caregivers commonly engaged in daily singing (74%) and talking (50%) with young children; reading/storytelling (36%) was less common [50]. There appeared to be an assumption that development will happen automatically if children’s basic needs are met, with little mention of the active role that caregivers, particularly mothers (as primary caregivers in this study), play in promoting child development. Several mothers reported that books and toys were more appropriate for children from preschool age and did not deem these appropriate for younger children. These findings concur with previous research that explored popular understandings of ECD in South Africa, further emphasising the importance of effective social behaviour change communication strategies to increase public awareness and understanding of young child development [17].

Safety concerns were significant barriers to children’s ability to play and explore outside the home. Excursions to the park or other recreational spaces were less commonly reported. Fears about physical harm to young children, especially extreme dangers, such as rape and kidnapping of children, were mentioned frequently and influence the ability of children to explore their environment outside the home. This also translated to safety concerns about the use of caregivers outside the immediate family or using group childcare, such as day care centres and childminders. Despite high levels of other forms of harm, such as unintentional injuries amongst young children in South Africa, exposure to extreme dangers (such as kidnapping), although much less frequent, seemed to overshadow day-to-day maternal concerns about the safety of children. This is consistent with findings from previous studies that found that the public in South Africa tends to be more concerned about extreme threats to child safety rather than more prevalent risk factors that can harm children’s health and well-being, such as exposure to extreme poverty and unintentional injuries [17, 51]. The revised Road to Health Book includes information on child injury prevention and protection from harm; however, this is an area that needs further development and strengthening [51, 52].

Information targeting caregivers, with a focus on caregiving, child development, prevention and management of common illnesses, and pregnancy, was identified as a gap. Health facilities and health workers were trusted sources of information, as well as the Road to Health Book, which was referenced by several mothers. However, participants felt that their interaction with the available information was “passive” as there were not always opportunities to ask questions or discuss the information with a health worker or other mothers. Internet searches and social media groups were also commonly used to access information, interact with peers around caregiving issues/concerns, or search for answers or advice. Besides the benefits of the increased access to information on the Internet, digital and mobile platforms in low- and middle-income settings like South Africa, there is also a concurrent growth in the spread of misinformation and marketing of unhealthy foods, specifically targeted at caregivers of young children [53–55].

The Road to Health Book is aimed at providing information and guidance to caregivers and health workers to ensure that the full range of nurturing care services is accessible to young children and their families and, thus, serves as a platform to effectively counter these practices if utilized optimally [40]. There has been a major focus on mass communication interventions, using a variety of platforms, including social media and radio, as well as the development of information and support materials for caregivers and health care workers [6]. However, evidence from this study indicates that there is a need to strengthen the interpersonal interactions between caregivers and health care workers as a way to clarify and reinforce the information and messages contained in the booklet and campaign. In addition, there needs to be opportunities for pregnant women and new mothers to share their experiences and problem solve around common childcare concerns with their peers as well as with health care workers, as part of routine practice within the health system.

This study is one of few to explore maternal perceptions of nurturing care and how this can be promoted for young children in resource-limited settings in Africa. We combined qualitative approaches to strengthen our exploration and understanding of mothers’ perceptions of nurturing care of young children in this context. We undertook several measures to minimise bias, including double coding of transcripts, checking and cross-checking analysis, ensuring that there was agreement amongst researchers, and having a fourth objective researcher affirming the thematic framework and analysis.

This study only focused on maternal perspectives, rather than including other caregivers. As highlighted in our findings, further research should explore the role of influential role players that support and assist mothers with caregiving. Focused consideration of the importance of female matriarchs, especially grandmothers, as well as the role of fathers and other influential males, in caregiving, needs to be explored and better understood to inform public health interventions. It is also necessary to conduct more in-depth explorations of caregivers’ norms and practices regarding childcare, including responsive care and child health and development, as well as how mothers deal with differences or discrepancies between their own and other prevailing family and community norms around childcare, health and development and nurses’ discourses and advice related to these. We did not explore caregivers’ perspectives of child behaviour and socioemotional development in as much detail or their thoughts and practices on the discipline of young children. This is an area that is largely understudied in our context and, thus, is another important area for future research exploration. Mixed methods research could build on this work, by exploring the practices and behaviours of caregivers in addition to their perceptions, as well as the effects of these on child outcomes.

6. Conclusion

These study findings can contribute to strengthening initiatives to support caregivers to provide nurturing care of young children in South Africa and other similar contexts. It points to the need for more targeted information and support for mothers and other caregivers around nurturing care, especially elements related to responsive care (including responsive feeding), child development and early learning, and how to promote safety in the home. Proactive communication and support strategies, through the provision of platforms and opportunities for mothers and other caregivers to engage with their peers and health care workers around the information shared through current initiatives, are required.

It also highlights the important role of the health system in supporting caregivers to provide nurturing care, and thus, it has a specific responsibility to use every contact opportunity to strengthen families’ efforts to promote the health, growth, and development of children.

Disclosure

Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged (Grant no. 113987). This study was also supported by the South African Medical Research Council and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the mothers who participated in the study and the research teams whose work we represent here.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.