Patient-reported quality of care in primary sclerosing cholangitis

Handling Editor: Luca Valenti

Abstract

Background

Management and follow-up strategies for primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) vary. The aim of the present study was to assess patient-reported quality of care to identify the most important areas for improvement.

Methods

Data were collected via an online survey hosted on the EU Survey platform in 11 languages between October 2021 and January 2022. Questions were asked about the disease, symptoms, treatment, investigations and quality of care.

Results

In total, 798 nontransplanted people with PSC from 33 countries responded. Eighty-six per cent of respondents reported having had at least one symptom. Twenty-four per cent had never undergone an elastography, and 8% had not had a colonoscopy. Nearly half (49%) had never undergone a bone density scan. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) was used in 90–93% in France, Netherlands and Germany, and 49–50% in the United Kingdom and Sweden. Itch was common (60%), and 50% of those had received any medication. Antihistamines were taken by 27%, cholestyramine by 21%, rifampicin by 13% and bezafibrate by 6.5%. Forty-one per cent had been offered participation in a clinical trial or research. The majority (91%) reported that they were confident with their care although half of the individuals reported the need for more information on disease prognosis and diet.

Conclusion

Symptom burden in PSC is high, and the most important areas of improvement are disease monitoring with more widespread use of elastography, bone density scan and appropriate treatment for itch. Personalised prognostic information should be offered to all individuals with PSC and include information on how they can improve their health.

Abbreviations

-

- AASLD

-

- American Association for the Study of Liver Disease

-

- AIH

-

- autoimmune hepatitis

-

- CCA

-

- cholangiocarcinoma

-

- EASL

-

- European Association for Study of the Liver

-

- ERN

-

- European Reference Networks

-

- IBD

-

- inflammatory bowel disease

-

- PBC

-

- primary biliary cholangitis

-

- PSC

-

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

-

- UDCA

-

- ursodeoxycholic acid

-

- UK

-

- United Kingdom

Key Points

An online patient survey about management and perceived quality of care was performed and 798 nontransplanted people with PSC from 33 countries responded. The symptom burden in PSC is high, and areas of improvement in clinical care are disease monitoring with more widespread use of elastography, bone density scan and appropriate treatment for itch. More support and information on prognostication and how people with PSC can improve their health including food, diet and supplements is warranted.

1 INTRODUCTION

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a rare progressive liver disease closely associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Progression is usually slow with mean time to liver failure or need for liver transplantation being around 20 years.1-3 However, the heterogeneity of PSC is large and varies from more active rapidly progressing disease with multiple severe symptoms such as jaundice, itch, bacterial cholangitis or cirrhosis complications to slowly progressive asymptomatic disease that is stable for decades. There is currently no medication that can slow down disease progression or decrease the risk of cancer. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is broadly used despite limited evidence of its efficacy, but many new potential treatments are being investigated.4, 5 One of the more feared complications is the development of malignancies in the liver, especially cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), which can occur at any disease stage. The risk for CCA is highest in older people or with recently diagnosed PSC with a lifetime risk of 8% and is a major cause of death in PSC.1, 3, 6, 7 Children more often present with concomitant autoinflammatory features with more pronounced elevated IgG, auto-antibodies and degree of inflammation seen at liver histology.8

Management and follow-up strategies for PSC vary considerably between centres and countries,9, 10 likely due to the lack of evidence-based practice in PSC. Furthermore, they vary according to the age of the patients due to differences in disease course. A recent survey showed substantial difference between specialised European centres in treatment and monitoring.10 Updated clinical practice guidelines for sclerosing cholangitis have recently been published by the European and American associations (EASL and AALSD),11, 12 both including the paediatric perspective. Such guidelines can contribute to improved quality of PSC care and the implementation of best practice globally. Because the rarity of PSC can lead to a lack of clinical experience in general gastroenterological practice, access to up-to-date recommendations is important for improving knowledge despite limited evidence.

Adoption of new guidelines by healthcare providers can be slow and adherence varies. For example, the United Kingdom (UK) audit found IBD screening and colonic cancer surveillance to be suboptimal in a large UK cohort of people with PSC,13 and treatment of cholestatic itch is inconsistent and undertreatment is common.14 A slow implementation may be due to multiple factors, and behaviour changes in populations and in healthcare systems are well known to take a long time. ERN RARE-LIVER is one of the 24 European Reference Networks (ERNs) approved by the ERN Board of Member States and co-funded by the European Commission. A key goal of the ERN RARE-LIVER is to improve rare liver disease care through the education of both patients and caregivers and by facilitating the implementation of best practice care recommendations.

Identifying the most important areas of improvement by asking patients about their experience of care is one way to increase physicians' awareness of the needs of people with PSC and to facilitate the implementation of best practice. ERN RARE-LIVER PSC Working Group is a platform from which such investigation can be undertaken.

The main aim of this study was therefore to assess patient-reported quality of care in people with PSC to identify and increase awareness of the most important areas for improvement.

2 METHOD

2.1 Survey and patients

A patient survey was developed in English by the physicians CS, NC, NJ and AB and patient representatives MW and AL. Each question was constructed from a patient perspective so that it was relevant and easy to understand. A combination of multichoice and open-ended questions was asked about the disease, symptoms, treatment, investigations and quality of care. Quality of care was evaluated by asking about ease of access to care, perceived knowledge and information, confidence rating of care and invitations to participate in clinical trials or research. The whole questionnaire is shown in Supplementary S1. Nine hundred and thirty-nine people completed the survey (141 had had a liver transplant, 798 had not). The survey questions were translated by members of the PSC Working Group (https://rare-liver.eu/about/members-and-partners-of-the-network).

Data were collected via the online survey (Supplementary S1) hosted on the EU Survey platform (supported by the European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/eusurvey/) in Dutch, British English, Croatian, Finnish, French, German, Hebrew, Italian, Macedonian, Portuguese and Spanish between 29 October 2021 and 29 January 2022. The survey was supported by patient representatives of ERN RARE-LIVER and members of the ERN RARE-LIVER PSC Working Group. No personal data from respondents were collected beyond asking which hospital each respondent attends for their liver disease. No ethics approval was necessary for this anonymous, online survey.

The survey was shared with ERN RARE-LIVER healthcare centres and patient organisations (https://rare-liver.eu/about/members-and-partners-of-the-network and https://rare-liver.eu/patients/patient-organisations) via the ERN RARE-LIVER e-newsletter. Individual patient organisations shared details of the survey within their own patient communities via newsletters, social media channels and their own websites. The survey was also published on the ERN RARE-LIVER webpage.

Because the survey was shared in open networks, it is not possible to accurately estimate the survey response rate. However, responses were received from participants in 36 countries around the world and included transplanted and nontransplanted respondents. The data were categorised into respondents living in European and non-European countries.

Only responses from nontransplanted individuals were analysed in detail (n = 798). They were reviewed against the recommendations in the EASL guidelines for management of PSC. Respondent ages were grouped as follows: Children: aged 7–15 years, young adults: 16–25 years, adults: 26–60 years and seniors: 61+ years. Selection of responses to open-ended questions (quotes) is used to support and give examples of the findings.

2.2 Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarised as means (SD) or as medians (interquartile range [IQR], lowest 25%–highest 25%) and compared with Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis H test with Dunn's multiple comparison post hoc analysis. Categorical variables were summarised as frequencies and percentages and compared with Fisher's exact test or χ2 test. Spearman correlation was used to assess the association between variables with multiple values. For statistical analysis and graphical presentation, the SPSS 25.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) and GraphPad Prism 9.4.1 (San Diego, California, USA) programmes were used. A two-sided probability value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Respondent characteristics and diagnosis

In total, 939 people from 36 countries responded to the survey. Fifteen per cent (141/939) were transplanted. The following analysis and results presented come from the data reported from 798 nontransplanted people with PSC from 33 countries (Table S2). Demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1 with a high frequency of concomitant IBD; most respondents were female. Two-thirds of the patients were diagnosed with PSC more than 6 months after first liver-related symptoms or abnormal blood tests (Table 1). The majority of patients, 63.8% (509/798), reported being treated at an academic referral centre and 23.4% (187/798) in a general hospital or a private clinic, and information on this was lacking in 12.9% (102/798).

| Patients with PSC | |

|---|---|

| n = 798 | |

| Female sex | 494 (62.0%) |

| Mean age, years (±SD) | 45.5 ± 15.7 |

| Children (7–15 years) | 22 (2.8%) |

| Young adults (16–25 years) | 75 (9.4%) |

| Adults (26–60 years) | 559 (70.1%) |

| Seniors (61+ years) | 142 (17.8%) |

| European | 740 (92.7%) |

| UK | 265 (33.2%) |

| France | 228 (28.6%) |

| Netherlands | 70 (8.8%) |

| Sweden | 67 (8.4%) |

| Germany | 57 (7.1%) |

| Other European countries | 53 (6.6%) |

| IBD | 432 (62.1%) |

| AIH overlap | 120 (15.2%) |

| Time between first symptom or abnormal laboratory test and PSC diagnosisa | |

| <6 months | 267 (33.5%) |

| 0.5–1 year | 171 (21.4%) |

| 1–2 years | 117 (14.7%) |

| 2–3 years | 60 (7.5%) |

| 3–5 years | 52 (6.5%) |

| 5–10 years | 54 (6.8%) |

| More than 10 years | 57 (7.1%) |

| Cirrhosis | 161 (20.2%) |

| Symptoms | 690 (86.5%) |

| Any medication for liver disease | 636 (79.7%) |

| Offered participation in a clinical trial or research study | 330 (41.4%) |

- a 2.5% (20) did not have a definitive PSC diagnosis.

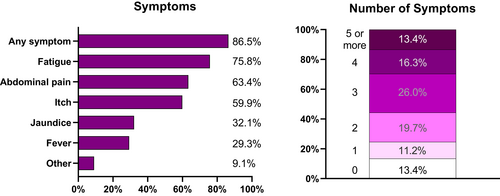

3.2 Symptom burden

Eighty-seven per cent of respondents reported having had at least one symptom. The most frequently reported symptom was fatigue (75.8%) followed by abdominal pain (63.4%) and itch (59.9%). Multiple symptoms were common, and more than half of all respondents reported three or more symptoms (Figure 1). Detailed information on frequency of symptoms was not collected in the interests of minimising the survey length and focussing on care. Responders with IBD vs. non-IBD had a similar symptom burden except for abdominal pain, which was more common in IBD responders 66.3% (287/432) vs. 57.2% (151/264), p = 0.019.

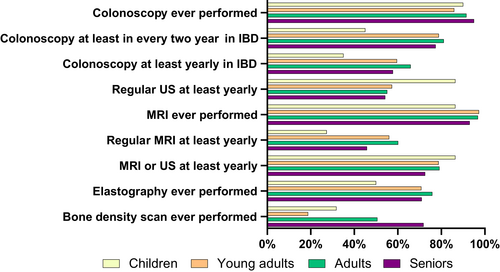

3.3 Investigations

Data on how PSC was monitored and contacts with healthcare were reported. Frequency of clinical visits, blood sampling and imaging varied between countries, shown in Supplementary Table S3. In our survey, 24.2% (193) had never undergone an elastography and 48.6% (388) had never had or did not have liver elastography regularly; 7.6% (61) had not had an ultrasound scan (US), and 27.2% (217) did not have this regularly. 11.4% (91) did not have regular scanning with either US or MRI. The use of regular liver elastography was more frequent in academic referral centres than in general hospitals, but nearly 40% of patients treated at an academic referral centre did not have a regular liver elastography (Table S3a).

Colonoscopy had never been performed in 8.1% (65). Of responders with PSC-IBD, 14.8% (64) had a colonoscopy less frequently than every 2 years. Investigations per age group are shown in Figure 2.

Half, 50.9% (406) of all respondents had ever undergone a bone density scan. This scan was more commonly performed in patients having concomitant autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) (62.5% vs. 48.8%, p = 0.02), in females ((55.3%) vs. males (43.6%), p = 0.002) and in older patients, the frequencies being: children 31.8%, young adults 18.7%, adults 50.6% and seniors 71.8%, (p < 0.001). No difference in frequency of bone density scans was seen in people with IBD (52.2%) vs. non-IBD (56.1%) responders. Detailed information about monitoring is shown in Tables S3a–c.

3.4 Treatment

Medical treatment varied between countries. The majority 79.7% (636) had taken medication for liver disease, 70.9% (566) had been treated with UDCA, and 24.4% (195) used calcium-vitamin D supplements (Table 2). There was a striking difference in the use of UDCA in European countries: UDCA was used in 90.8% (207) in France, 90.0% (63) in the Netherlands and 93% (53) in Germany compared with only 50.6% (134) in the UK and 49.3% (33) in Sweden. Immunosuppression was more commonly used in people with concomitant AIH, and vancomycin was rarely used and mostly reported in children with a decreasing trend of usage in older age groups (from younger to older: 22.7% in children, 5.3% in young adults, 0.5% in adults and 0.0% in seniors). A detailed summary of treatments is shown in Table 2.

| Any medication | UDCA | Azathioprine | Steroids | Mycophenolate mofetil | Vancomycin | Calcium/Vitamin D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (798) | 636 (79.7%) | 566 (70.9%) | 87 (10.9%) | 54 (6.8%) | 11 (1.4%) | 12 (1.5%) | 195 (24.4%) |

| AIH (115) | 115 (95.8%) | 566 (70.9%) | 59 (49.2%) | 43 (35.8%) | 10 (8.3%) | 5 (4.2%) | 52 (43.3%) |

| No AIH (678) | 521 (76.8%) | 476 (70.2%) | 28 (4.1%) | 11 (1.6%) | 1 (0.1%) | 7 (1.0%) | 143 (21.1%) |

| IBD (432) | 337 (77.8%) | 290 (67.0%) | 53 (12.2%) | 31 (7.2%) | 6 (1.4%) | 11 (2.5%) | 107 (24.7%) |

| No IBD (264) | 218 (82.6%) | 203 (76.9%) | 22 (8.3%) | 15 (5.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 69 (26.1%) |

| Children (22) | 22(90.9%) | 15 (68.2%) | 8 (36.4%) | 4 (18.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (22.7%) | 7 (31.8%) |

| Young adults (75) | 56 (74.7%) | 43 (57.3%) | 7 (9.3%) | 7 (9.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (5.3%) | 11 (14.7%) |

| Adults (559) | 441 (78.9%) | 398 (71.2%) | 68 (12.2%) | 41 (7.3%) | 9 (1.6%) | 3 (0.5%) | 135 (24.2%) |

| Seniors (142) | 119 (83.8%) | 110 (77.5%) | 4 (2.8%) | 2 (1.4%) | 2 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 42 (29.6%) |

Itch was reported by 59.9 (478) of all responders, but only half of them (49.6%, 237) had received any medication for itch. Antihistamines were taken the most, 27.2% (130) in patients with itch, followed by cholestyramine (20.7%, 99) shown in Table 3.

| Medication | All (798) | In people with itch (478) |

|---|---|---|

| Any medication for itch | 253 (31.7%) | 237 (49.6%) |

| Antihistamine | 143 (17.9%) | 130 (27.2%) |

| Bezafibrate | 33 (4.1%) | 31 (6.5%) |

| Colestyramine | 102 (12.8%) | 99 (20.7%) |

| Naltrexone | 15 (1.9%) | 14 (2.9%) |

| Rifampicin | 65 (8.1%) | 62 (13.0%) |

| Sertraline | 11 (1.4%) | 11 (2.3%) |

3.5 Perceived quality of care

The majority (58.3%) reported that it was very easy or quite easy to contact their team, 22.7% (181) found it neither difficult nor easy and 15.8% (126) found it difficult or very difficult. There were no significant differences seen between age groups or countries. Information about PSC at time of diagnosis was reported as sufficient by 44.2% (353), too little by 46.1% (368) and too much by 2.1% (17). The amount of information given at diagnosis for children and young adults was sufficient for 36.4% (8) and 44.0% (33), too little for 50.0% (11) and 44.0% (33) and too much for 9.1% (2) and 4.0% (3), respectively. Of adults and seniors, 42.8% (239) and 51.4% (73) reported having sufficient information at diagnosis, too little in 48.1% (269) and 38.7% (55), and too much in 2.0% (11) and 0.7% (1), respectively. Twenty-eight per cent (22) reported that they had sufficient information at time of the survey. A lack of information was more frequently reported by those with a more recent diagnosis. High confidence in care was reported by the majority who totally or mostly agreed that they were confident in the medical care they received for PSC (435, 54.5%). Lack of confidence in the care was reported by 8.9% (71). There were no obvious differences in confidence in care between age groups.

Half of the respondents indicated that they needed more information about ‘Food, diet and supplements’ (52.6%), ‘Prognosis’ (49.6%) and ‘How I can improve my health’ (48.0%). A list of information needs is presented in Table 4. As many as 330 (41.1%) people with PSC reported having been offered participation in a clinical trial or research.

| Topic of Information | All (798) |

|---|---|

| Food, diet and supplements | 420 (52.6%) |

| The disease | 199 (24.9%) |

| How I can improve my health | 383 (48.0%) |

| Prognosis | 396 (49.6%) |

| Reasons for tests, scans, colonoscopies, etc. | 92 (13.6%) |

| PSC and pregnancy | 72 (9.0%) |

| Liver transplantation | 168 (21.1%) |

| Complementary medicine | 205 (25.7%) |

| Transferring from paediatric care to adult care | 31 (3.9%) |

| Other | 34 (4.3%) |

A comprehensive comparison between the 2022 EASL clinical practice guidelines for sclerosing cholangitis is shown in Table 5.

| Recommendation | Patient-reported current practice |

|---|---|

| Liver elastography and/or serum fibrosis tests at least every 2 to 3 years (LoE 3, strong recommendation, 96% consensus) | 24% never had elastography |

| Liver ultrasound and/or abdominal MRI/MRCP every year (LoE 3, weak recommendation, 96% consensus) | 78% are investigated with MRI or ultrasound every 12 months or more often |

| Assessment of bone mineral density is recommended in all people with PSC at the time of diagnosis using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA). (LoE 4, strong recommendation, 92% consensus) | 51% had ever had a bone density scan |

| UDCA at doses of 15-20 mg/kg/d can be given since it may improve serum liver tests and surrogate markers of prognosis. (LoE 1, weak recommendation, 76% consensus) | 71% are treated with UDCA |

| Long-term use of antibiotics is not recommended for the treatment of PSC in the absence of recurrent bacterial cholangitis (LoE 3, strong recommendation, 100% consensus) | 23% of children with PSC was treated with vancomycin |

| Pharmacological treatment of moderate to severe pruritus in sclerosing cholangitis with bezafibrate or rifampicin is recommended (LoE 4, strong recommendation, 83% consensus) | 6.5% of people with PSC and itch was treated with bezafibrate and 13% with rifampicin |

| Ileocolonoscopy with biopsies from all colonic segments including the terminal ileum, regardless of the presence of lesions, is recommended at the time of PSC diagnosis (LoE 3, strong recommendation, 100% consensus) | 8% had never had colonoscopy |

| Initial expert consultation for people with PSC at diagnosis and referral for those with symptomatic and/or progressive PSC to an experienced centre with ready access to PSC clinical trials and a dedicated multidisciplinary team are recommended (LoE 5, strong recommendation, 100% consensus) | 41% had been offered participation in clinical trials or research |

4 DISCUSSION

In this ERN-initiated global survey with 798 nontransplanted respondents with PSC, we report views from a patient perspective about symptom burden, routine care and monitoring, treatments and perceived quality of care. Care for PSC varies between countries. In general, overall disease monitoring is suboptimal, with low frequencies of important routine investigations for some individuals, for example colonoscopies, elastographies, bone density scans and imaging, and in some cases, these investigations have not been performed at all. Medical treatments used also vary considerably between countries. Similar findings were reported by healthcare providers in a recent survey of PSC physicians from expert ERN healthcare centres conducted in 2020.10

One important issue and unmet need for people with PSC is prognostication.12 In this context, the low use of elastography in PSC needs immediate attention. Despite nearly two-thirds of responders being treated in academic referral centres, only 43% of respondents reported having regular elastography and 24% never having had this scan. This is surprisingly low since elastography has been used in clinical hepatology for more than a decade and has impact on management if cirrhotic stage is diagnosed.15

‘I read about best practice for care of those with PSC, but specialist does not agree with the regularity therefore this is not offered. He says he'll be led by my blood results’.Responder ERN554, UK

‘As I grow older, I am monitored less frequently. This causes anxiety’.Responder ERN830, UK

‘I would like to know my prognosis and life expectancy for these diseases because the internet data is old and frightening’.Responder ERN431, France

The risk of osteopenia in PSC is lower than in primary biliary cholangitis (PBC),20 and bone density has been reported to reduce by 1% per year for people with PSC.21 The mechanism for bone loss in PSC is suggested to be associated with Th17-mediated inflammation not associated with disease duration or liver fibrosis, like in PBC.22 The very low frequency of bone density scanning in our survey population is striking where only half have ever undergone a bone density scan, although higher (62%) in people with PSC and AIH. Only 24% take calcium-vitamin D supplements.

‘It is incredibly difficult to get in touch with my specialist ….’Responder ERN892, UK

‘I feel very alone, my doctor refers me to the gastroenterologist whom I cannot reach. Messages left with his secretary are not answered’.Responder ERN688, France

‘I went to the ER several times because of fatigue, fever and pain. I have never felt that they take my PSC into consideration, they always tell me that I have no UC flare and they send me home with no painkillers or any other help’.Responder ERN33, Sweden

‘I feel like knowledge of PSC is very poor amongst GP's. I fear if I have an attack that I will not be able to contact my specialist, nor will my local hospital have knowledge of PSC’.Responder ERN551, Ireland

‘I would like to receive information about the disease from a specialist team and also to know if it is advisable to go to a nutritionist to improve my diet so as not to worsen symptoms’.Responder ERN207, Spain

The relatively high proportion of respondents of 41% who had been offered participation in research is encouraging. This figure may be overestimated due to the selection of responders being aware of such opportunities through their patient organisation or ERN. People with PSC are in general engaged and interested in research.24 EASL highlights the importance of expert consultation for people with PSC at diagnosis and referral for those with symptomatic and/or progressive PSC to an experienced centre with ready access to PSC clinical trials and a dedicated multidisciplinary team.

Medications, including UDCA, taken by respondents varied, particularly between countries and may be a reflection on local prescribing policies. In contrast to earlier guidelines,18 the use of medium-dose UDCA (15–20 mg/kg/d) is now stated as a treatment option in PSC, in keeping with current practice in many centres. Despite recommendation against oral vancomycin outside clinical trials in the guideline for adult patients, there seems to some use of oral vancomycin in the paediatric population (22.7%). The heterogeneous treatment regimes in different countries may make recruitment for clinical multicentre clinical trials of new drugs challenging.

In line with previous patient surveys, fatigue, abdominal pain and itch were the three most commonly reported symptoms.25 It is important to consider fatigue as a discrete symptom but also related to itch and consequent sleep disturbance. However, less than half of those who reported itch had been given a treatment for it. The most commonly reported treatment for itch was antihistamines, a medication known to be ineffective in cholestatic itch and consequently not recommended in clinical practice. Bezafibrate or rifampicin is now recommended as first-line treatment of moderate-to-severe pruritus.12

This study has limitations. Most importantly is the potentially low representativeness of respondents and selection bias. Most respondents in our survey were female, which does not reflect the well-known male predominance seen in PSC. However, this was expected since more women engage with patient groups than males. We also failed to effectively reach out to patients in some countries, and responders from the UK and France are clearly overrepresented. The UK and France have strong patient organisations, and representatives from these countries were deeply involved in this work, which likely influenced the response rate. However, since PSC is a rare disease, not every country has PSC patient representation, or has a patient organisation with sufficient capacity to engage to this extent (understandably, as some are very small patient organisations, typically a single person, often a PSC patient themselves, volunteering their time). We tried to reduce potential barriers to participation by translating the English survey into other languages, engaging with known PSC and liver patient organisations such as the European Liver Patients Association as well as the ERN RARE-LIVER physicians for dissemination. There is an urgent need to raise awareness of PSC in countries where patient engagement is low or nonexistent. Recall bias is an obvious problem. The low figures reported on investigations may be underreported. We did not use a validated questionnaire and the translated versions did also not undergo a validation process. Parents/caregivers responded on behalf of the youngest patients, and misinterpretation of symptoms and confidence may not accurately reflect the child's view. It was not possible to estimate the survey response rate due to the openly distributed invitations to take part.

Despite the number of limitations, this study has some strengths. The survey was open globally and translated into 11 languages, allowing more people with PSC to access the survey in their native languages, rather than English-only questions.

5 CONCLUSION

Our findings show that symptom burden in PSC is high, and areas of improvement are disease monitoring with more widespread use of elastography, bone density scanning and colonoscopy, and treatment for itch. Personalised prognostic information should be offered to all individuals with PSC and include information on diet and how they can improve their health. Current practice needs to improve and change if current clinical practice recommendations are to be universally followed. The rarity of PSC means that extensive clinical experience can be limited and timely referral to centres of expertise is critical.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MW, AB, NJ, NC, AL and CS contributed to concept and design. MW, NC, AL, AM, HL, MC, JM, AL, NJ, CS and AB contributed to survey development. DT contributed to statistical analysis. MW and AB contributed to first draft. All authors contributed to revision of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the patient organisations for disseminating this survey to people living with PSC https://rare-liver.eu/patients/patient-organisations and in particular the following individuals for translating the survey: José Willemse, Tarja Teitto-Tuckett, Angela Leburgue, Sam Dashti, Sindee Weinbaum, Билјана Мирческа.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors do not have any disclosures to report.

CLINICAL TRIAL NUMBER

NA.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available after contact with David Assis, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary.