Prospective Evaluation of Missed Musculoskeletal Injuries in Trauma Prevent Study

This study was carried out at Liverpool Hospital, Sydney, Australia.

ABSTRACT

Background

Physiotherapists are not routinely involved in tertiary survey of trauma patients but are well equipped to perform the musculoskeletal component of the tertiary survey (MSK tertiary survey) to detect any injuries that are missed during primary and secondary surveys.

Aim

To observe and evaluate MSK tertiary surveys completed by physiotherapists in the early identification of missed musculoskeletal injuries in trauma patients.

Methods

The study included a convenience sample of patients over 18 years old admitted under the Trauma team. Patients were allocated to P group if the physiotherapists conducted MSK tertiary survey before the trauma team. Patients were allocated to T group if the admitting Trauma team conducted a tertiary survey before the physiotherapists. McNemar's test was used to compare the discordance of new findings and missed injuries between the Trauma team's tertiary survey and the physiotherapists’ MSK tertiary survey within each of the groups.

Results

Two-hundred twenty-four patients were enrolled into P group and 436 patients were enrolled into T group. In the T group, 26 patients (6%) were identified with new confirmed injuries, of which physiotherapists identified 8 patients (1.9%). In the P group, 8 patients (4%) were identified with confirmed injuries, of which, physiotherapists identified 3 patients (2.4%). The discrepancies of identifying missed injuries between the trauma teams and physiotherapists in T or P group were not significant (p = 0.81, p = 0.25 respectively). No adverse events were reported.

Conclusion

Physiotherapists can conduct MSK tertiary surveys safely in the care of trauma patients as an adjunct to Trauma team-led tertiary survey to identify any missed musculoskeletal injuries in admitted trauma patients.

1 Introduction

Restoring trauma patients to their pre-injury status is the ultimate goal of any trauma service [1]. A major trauma service, equivalent to level 1 trauma service, provides a continuum of care that involves initial injury management to recovery, rehabilitation and discharge in an orderly fashion with minimal complication and referral to community services as required [1, 2]. In Australia, there were 18,269 major trauma cases reported in the Australian Trauma Registry (ATR) between 2013 and 2015 [3]. The most common mechanism of injury within this period was road trauma (44%) and falls (35%).

Liverpool Hospital is located in southwestern Sydney and is one of 5 level 1 major Trauma Centres in metropolitan Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Trauma care is provided by rostered specialty surgery teams, such as Trauma/General surgery as well as consulting subspecialty surgical teams 7 days a week. Trauma patients are admitted to one of the surgical wards that specialise in trauma management. At Liverpool Hospital, tertiary surveys are conducted by surgical or specialist registrars in surgical training who have completed Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) training.

A rapid primary survey to immediately identify and manage life-threatening injuries followed by a head-to-toe secondary survey, supplemented with diagnostic testing, is the standard of care as the first step in the reception and management of a severely injured patient [4]. This can sometimes result in smaller and more subtle injuries not being diagnosed until later.

Tertiary surveys have been shown to be an important method of screening for these injuries in trauma patients [5-7]. It differs from the secondary trauma survey as defined by ATLS in that it is performed outside the early resuscitative period and has the advantage of time, in allowing the results of all investigations to be collated and finalised. A thorough re-examination of patients, as they regain consciousness and activity, is also recommended [8]. Despite this structured approach to the delivery of care to the trauma patient, it is recognised that some injuries can still escape detection in hospital [8, 9].

Missed or delayed recognition of injuries may occur anywhere from 1% to 40% in any trauma institution [10]. The term “missed injury” itself is defined in many different ways in the literature often because of the use of arbitrary time endpoints. The National Trauma Database of the American College of Surgeons defines missed injury as an “injury-related diagnosis discovered after the initial workup is completed and the admission diagnosis is determined” [2, 6, 7, 9]. Janjua et al., reported missed musculoskeletal injuries rate of 29% in their study [7]. Although not often life-threatening, a missed injury usually creates functional difficulties for the patient. This includes delaying recovery and return to school or work in some patient populations, or increasing morbidity and mortality in other groups, especially the frail and elderly populations, if the injury requires immobilisation or further surgery. Timely identification of all injuries is important so appropriate treatment can be undertaken. Any missed injuries can delay the patient's rehabilitation progress and have the potential to further delay discharge planning.

Physiotherapy plays a critical role in the management of trauma patients and patients are often referred to physiotherapists after a tertiary survey is conducted by the Trauma team for assessment and treatment options including respiratory therapy, musculoskeletal therapy, early mobilisation or rehabilitation to facilitate discharge planning from hospital [11]. It is a standard practice for physiotherapists to conduct a comprehensive assessment before providing treatment to trauma patients. It is during this time that physiotherapists may identify musculoskeletal injuries that were missed at tertiary survey. Not uncommonly this can occur when the patient first attempts to weight bear with physiotherapy. Although physiotherapists are often regarded as experts in identifying and assessing musculoskeletal injuries, their initial assessment may not include head-to-toe re-examination of a trauma patient.

To date, there are limited studies investigating the feasibility of physiotherapists performing musculoskeletal component of the tertiary survey (MSK tertiary survey) to identify musculoskeletal injuries. Currently, physiotherapists are not routinely involved in conducting MSK tertiary surveys to identify musculoskeletal injuries in trauma patients but are well equipped to do so. The aim of this study was to compare the physiotherapists’ MSK tertiary survey findings to Trauma team tertiary survey findings in identifying missed musculoskeletal injuries in patients with trauma.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

This was a prospective evaluation study conducted at the Liverpool Hospital, a University of New South Wales (UNSW)-affiliated, verified level 1 trauma centre in Sydney New South Wales, Australia. Full ethical approval was obtained from the Liverpool Hospital ethics committee (HREC/13/LPOOL/60). The study was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12613000722796).

2.2 Participants

Any admitted trauma patient over the age of 18 years was eligible for enrolment into the study between January 2014 and January 2015. Patients who were discharged from the emergency department (ED) or did not survive the first 24 h following admission were not included. A standard tertiary survey was performed by the trauma team. The survey included whole patient assessment which included re-examining patient's head, face, neck, chest, upper limbs, abdomen, pelvis, lower limbs, spine and examining final reports of all the radiological findings in addition to reviewing of all investigations. A local health district tertiary survey assessment form was used to document tertiary survey findings by the trauma team, as per usual practice. The MSK tertiary survey included comprehensive head-to-toe re-examination of the musculoskeletal system of the patient, and examination of consultant reviewed radiology findings to identify any musculoskeletal injuries. The MSK tertiary survey was completed as a part of physiotherapy initial assessment. Informed consent was obtained as per usual care before a physiotherapy initial assessment. Fourteen physiotherapists including weekday and weekend staff volunteered to participate in the study and performed tertiary surveys on all patients enrolled in the study.

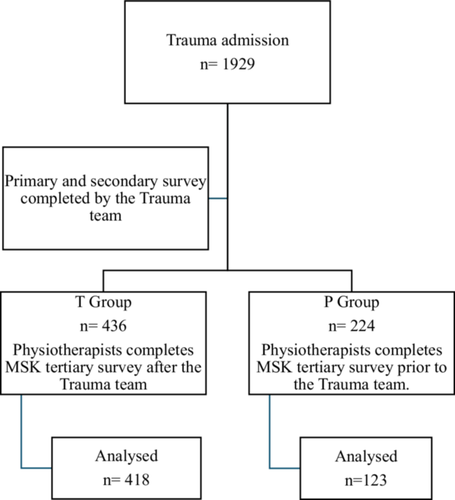

When the trauma call was activated, the study investigators were also alerted of a possible trauma admission. All patients had primary and secondary surveys conducted by admitting trauma team as per standard trauma care. The study investigators then alerted the physiotherapists in corresponding wards of the trauma patients requiring MSK tertiary surveys. Patients were allocated into groups depending on the timing of the tertiary survey by the admitting Trauma teams. Patients were allocated to the P group if physiotherapists conducted a MSK tertiary survey before the admitting Trauma team. Patients were allocated to the T group if the admitting Trauma team conducted a tertiary survey before the physiotherapist. Allocation of groups was through convenience sampling over the period of 12 months. See Figure 1.

The usual practice for physiotherapists when assessing trauma patients is to notify the trauma team of any identified missed injuries after the physiotherapy initial assessment. Therefore, in the P group, any new injuries that were identified by the physiotherapists were notified to the Trauma team immediately, as per usual care. In the T group, the study investigators were physiotherapists who were conducting MSK tertiary surveys blinded from the Trauma teams’ tertiary survey if there were no other injuries found by the Trauma team. If there were new injuries identified by the Trauma team's tertiary survey, study physiotherapists were informed of the injuries before conducting MSK tertiary surveys, thus not blinded from the Trauma team's tertiary survey findings. In accordance with tertiary survey practice, physiotherapists conducted MSK tertiary surveys in coordination with the confirmation of final radiology reports.

Before the commencement of the study, a competency checklist was developed by the trauma surgeon and trauma surgical fellow encompassing all aspects of MSK tertiary survey as per the ATLS guidelines. The research team members were then provided with training by the trauma surgeon and the fellow. This included an education session on the principles of tertiary survey followed by demonstrations of MSK tertiary survey on a mock patient, including documentation of the tertiary survey form. The physiotherapists practiced on one another during the practical session and observed the trauma surgeon's or surgical fellow's MSK tertiary surveys on patients until they were confident to perform MSK tertiary surveys themselves. Physiotherapists then performed MSK tertiary surveys on patients under the supervision of either the trauma fellow or the research team members, who observed and provided correction and feedback as needed. The surgeon or the fellow completed the competency checklist on the team members. Once deemed competent, the team members provided training to the remaining volunteered physiotherapists. Once the competency checklist was completed, the physiotherapist was able to perform the MSK tertiary survey on study participants.

A missed injury in this study was defined as any injury not identified following primary and secondary surveys as well as imaging conducted within 24 h of admission that is subsequently identified. The definition of the missed injury in this study is comparable to one of the 3 types of missed injuries defined and evaluated by Keizers et al., 2014.

The primary outcome was a comparison of the number of missed musculoskeletal injuries between groups. The secondary outcomes were a comparison of types of missed injury findings between groups and the number of MSK tertiary surveys completed by physiotherapists in the P group.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Due to limited evidence in the literature regarding the prevalence of missed injuries from MSK tertiary surveys conducted by physiotherapists in patients with trauma and the difficulties in calculating the number of patients assessed by study physiotherapists above their usual caseload, we recruited a convenience sample based on a period of 12 months.

McNemar's test was used to compare the discordance of new findings between the Trauma team's tertiary survey and the physiotherapists’ MSK tertiary survey within each of the groups. Descriptive data with percentages were used for patients’ demographics. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 8.2 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC).

3 Results

Trauma patients who were enrolled into the study were seen and assessed by the study physiotherapists, 7 days a week, in addition to their usual caseload.

There were 1929 patients admitted under the Trauma team after trauma call activation from January 2014-January 2015. A total of 660 patients were enrolled into the study, with 224 patients enrolled into the P group, and 436 patients enrolled into the T group. The physiotherapists conducted MSK tertiary surveys on every patient in the P and T groups. Demographic data is shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in demographics between groups. As a combined group, there were more male patients (64%) than females (36%), and 31% of the total study sample were admitted after a fall. Average ISS was 11.6 (8.8) with median length of stay in the hospital and ICU as 4 days and 0 days, respectively.

| Total trauma admission N = 1929 | T group N = 436 | P group N = 224 | Total study sample N = 660 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (SD) | 51.3 (21.3) | 50.6 (21.6) | 51.1 (21.4) |

| Gender (%) | |||

| Male | 267 (61.5) | 155 (69.2) | 422 |

| Female | 167 (38.5) | 69 (30.8) | 236 |

| Falls (%) | |||

| < 1 m | 79 (59.9) | 46 (63.9) | 125 |

| 1–5 m | 49 (37.1) | 20 (27.8) | 69 |

| > 5 m | 4 (3) | 6 (8.3) | 10 |

| Total falls | 132 | 72 | 204 (30.9) |

| ISS (SD) | 11.7 (8.7) | 11.5 (9.1) | 11.6 (8.8) |

| LOS ICU mean (SD) days, [median] days | 0.5 (3.6) [0] | 0.5 (1.9) [0] | 0.5 (3.1) [0] |

| LOS Hospital mean (SD), [median] days | 8.4 (12.2) [4] | 7.2 (8.9) [4] | 8.0 (11.2) [4] |

- Note: N = sample size, SD = standard deviation, m = metre, ISS = Injury Severity Score, LOS = Length of stay, ICU = Intensive care unit.

In the T group, the Trauma team identified 16 confirmed injuries in 16 patients compared to the physiotherapists who identified 14 confirmed injuries in 14 patients. Physiotherapists identified 8 (1.9%) new injuries in 8 patients where the Trauma team had not identified new injuries. The discrepancy between teams was not statistically different (p = 0.81), see Table 2. Physiotherapists identified 2 missed injuries in 2 patients for which no tertiary surveys were completed by the Trauma team. The full list of missed injuries identified by physiotherapists and the Trauma team in the T group are tabulated in Table 3. Eighteen patients did not have tertiary surveys completed by the Trauma team in the T group.

| T group | Physiotherapy team | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trauma Team | New missed injury, n (%) | No new missed injury, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

| New missed injury, n (%) | 6 (1.4)† | 10 (2.4) | 16 (3.8) | |

| No new missed injury, n (%) | 8 (1.9) | 394 (94.3) | 402 (96.2) | |

| Total | 14 (3.4) | 404 (96.7) | 418 (100) | |

- Note: N = sample size, †= Both teams identified injuries which were confirmed by further imaging.

| Confirmed injuries identified by Trauma team | Confirmed injuries identified by Physiotherapy team | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ISS | Mechanism | Injury | LOS | Age | ISS | Mechanism | Injury | LOS |

| 38 | 11 | Assault | #6th rib | 3 | 81 | ‡ | Fall < 1 m | Supraspinatus tear | 29 |

| 23 | ‡ | MVC | #L1 | 0 | 33 | 10 | MVC | #metartasal | 15 |

| 20 | 29 | MBC | #ulna | 8 | 62 | 33 | MBC | #scaphoid | 14 |

| 20 | 9 | Assault | #face | 2 | 23 | 2 | MBC | #great toe | 12 |

| 41 | ‡ | MBC | #MCP | 5 | 56 | 22 | MVC | #ACJ | 8 |

| 76 | 43 | Fall 1–5 m | SDH | 19 | 46 | 29 | MVC | #fibula, cuboid, metartarsal | 25 |

| 45 | 41 | Fall 1–5 m | #radius and ulna | 59 | 35 | 22 | MBC | #radius | 26 |

| 65 | 13 | Fall < 1 m | #scaphoid | 15 | 77 | 5 | Pedestrian | #malleolus | 1 |

| 34 | 4 | Fall 1-5 m | #calcaneus | 7 | 54§ | 36 | Glider | #radius | 66 |

| 51 | ‡ | Pedestrian | #T12, L1,2, sacral | 1 | 69§ | 27 | MVC | #ulna | 17 |

- Note: ISS = Injury Severity Score, LOS = length of stay in days, m = metre, ‡ = missing ISS data, § = missing trauma team tertiary surveys, MVC = motor vehicle crash, MBC = motor bike crash, T = thoracic spine, ACJ = acromioclavicular joint, MCP = metacarpal phalangeal joint, SDH = subdural haematoma, L = lumbar spine.

In the P group, a total of 4 missed injuries were identified by the physiotherapists in 4 patients. Physiotherapists found 3 confirmed missed injuries (2.4%) in 3 patients where the Trauma team did not identify any new injury in the same patients, and there was no new missed injury identified by the Trauma team when physiotherapists did not identify any new injury. The discrepancies between the teams were not significant (p = 0.25), see Table 4. Both teams identified the same missed injury on the same patient. Physiotherapists identified 4 missed injuries in 4 other patients in the group, however, there were no tertiary surveys completed by the Trauma team on these patients. See Table 5 for a full list of identified missed injuries by the physiotherapists in the P group. There were 101 patients without the Trauma team's tertiary survey.

| P group | Physiotherapy team | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trauma Team | New missed injury, n (%) | No new missed injury, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

| New missed injury, n (%) | 1 (0.8)¶ | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| No new missed injury, n (%) | 3 (2.4) | 119 (96.8) | 122 (99.2) | |

| Total | 4 (3.3) | 119 (96.8) | 123 (100) | |

- Note: N = sample size, ¶= Both teams identified injuries which were confirmed by further imaging.

| Confirmed injuries identified by Physiotherapy team | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ISS | Mechanism | Injury | Length of stay |

| 28 | 22 | MVC | #naviculum | 18 |

| 37§ | 22 | MVC | #ilium, acetabulum | 24 |

| 64 | 14 | MVC | #thumb | 7 |

| 57§ | 10 | kicked by a horse | #nose | 11 |

| 61§ | 24 | pedestrian | #metatarsal | 19 |

| 20§ | 24 | MBC | #mandible | 19 |

| 28 | 4 | struck by falling object | MCL tear | 6 |

- Note: ISS = Injury Severity Score, Length of stay in days, §= missing trauma team tertiary surveys, MVC = motor vehicle crash, MBC = motor bike crash, MCL = medial collateral ligament.

There were no severe adverse events reported in either of the groups.

4 Discussion

Our study was conducted to observe and evaluate if a MSK tertiary survey by physiotherapists is feasible in the early identification of potential missed musculoskeletal injuries in patients admitted to the hospital with injury. The MSK tertiary survey by physiotherapists in this study is not intended to replace a formal tertiary survey, which encompasses more than just the musculoskeletal system, and is an examination of the whole patient requiring medical input. To date, no other studies have demonstrated the outcomes of physiotherapists conducting MSK tertiary surveys as part of their initial patient assessments in patients with trauma.

Janjua et al. [7] conducted a prospective study investigating the role of tertiary survey at Liverpool Hospital in 1996 on a population of 206 patients. They reported that 65% of the study population had missed injuries, Nineteen years later, the Trauma team in our study found 16 (3.6%) patients out of 418 patients in the T group and 1 (0.8%) patient out of 123 patients in the P group with missed injuries in our study with a prevalence rate of 3.1% in the combined group. The number of missed injuries identified by the Trauma team in our study is significantly less compared to the previous study findings from [7]. Since 1996, there have been initiatives to further enhance the trauma services at Liverpool Hospital. Initiatives include Trauma team training, focusing on clinical and nontechnical skills and standardising tertiary survey as a part of trauma assessment, and recruitment of medical specialists whose specialty and interest are in trauma care. There have been substantial advancements in imaging quality, particularly in cross-sectional imaging, quality of reconstructions, detail of imaging, use of contrast and reliability of cross-sectional imaging techniques. MRI has been used more than previously. Interventional radiology has seen remarkable improvements, notably, advancements in Interventional radiologists’ techniques to image and intervene from an intravascular perspective. Our study may reflect the result of such a change in the Trauma service at Liverpool Hospital since 1996. However, there were a total of 119 patients (18%) who did not have documented tertiary surveys in our study. It is beyond the scope of this study to investigate the reasons for the non-completion of the tertiary survey by the Trauma team nor the non-completion rate in the remaining 1269 patients who did not participate in the study. Possible reasons for Trauma team's non-completion rate in the study are likely multifactorial. These include the institution undergoing a transition from paper medical records (including a paper-based tertiary survey form with patient diagram) to electronic medical records over this time; difficulty in locating tertiary survey forms in the wards; or miscommunication within or between medical teams.

The novel finding of this study is that the physiotherapists were able to safely conduct MSK tertiary surveys and identify missed musculoskeletal injuries in patients with trauma, and achieve results similar to that of the Trauma team. Our findings also suggest that physiotherapists’ MSK tertiary survey is a feasible adjunct to existing trauma care processes. There were no reported adverse events. Most of the missed injuries identified by physiotherapists were fractures of skeletal bones, such as shoulder, elbow, wrists, hands, knees, ankles, and foot from the total of 8 patients with missed injuries. In comparison to the Trauma team, physiotherapists identified 14 (3.4%) patients out of 418 patients in the T group and 4 (3.3%) patients out of 123 patients in the P group with a prevalence rate of 3.3%. The discrepancies between teams in each group were not statistically significant. However, the type of injuries that were identified could be clinically significant. Fifteen patients with missed injuries identified by physiotherapists were less than 65 years old and may be working. Though not life-threatening injuries, their missed injuries required further investigation, treatment, and further surgery in some patients. It was beyond the scope of this study to investigate further, however, patients with missed injuries are reported to have difficulty returning to pre-injury level activities of daily living, take longer time to return to work and require ongoing follow-up with their general practitioner, physiotherapists and occupational therapists at 1 and 6 months [12]. In normal practice, physiotherapists await clearance from a tertiary survey by the trauma team before treating or mobilising trauma patients, and do not repeat head to toe examination. While physiotherapists anecdotally use structured assessment tools for trauma patients, it is not standard practice to perform a thorough re-examination of these patients to include body regions that are not concerned from the mechanism of injury.

In our experience, missed injuries were typically found in areas where the initial investigations or radiology had not been conducted, particularly when the patient was ambulating for the first time with the physiotherapist. Therefore, physiotherapists performing MSK tertiary surveys is an additional layer of assessment above usual practice.

There are some limitations to this study. The authors acknowledge that a convenience sample study may not fully represent the population of trauma patients. Our decision to use a convenience sample was influenced by practical constraints. At the time of the study, there was no dedicated physiotherapists designated specifically to the Trauma service at Liverpool Hospital. Furthermore, this was an unfunded study where study participants were seen by 14 volunteering physiotherapists above their usual caseload, surgeon's and fellow's time spent in training and supporting the physiotherapists was in-kind support.

As our study was not a randomised controlled study, it is possible that not blinding physiotherapists in the T group's result from the trauma team's findings may have influenced the results. However, blinding trauma team's new findings would have been impractical and a change in practice. If a missed injury that is identified by trauma team is of urgent nature (e.g. fracture of a vertebra), such findings should be noted by the physiotherapist to avoid conducting unnecessary assessments such as log rolling patient. Furthermore, the authors acknowledge that patients not being randomised to allocation increases selection bias, affecting the comparability between groups.

The scope of MSK tertiary survey for physiotherapists in this study did not extend beyond the musculoskeletal system, therefore physiotherapists’ identification or diagnosis of injuries is unlikely to extend beyond this. Any abnormal findings such as pain on palpation on the abdomen or reduced hearing were reported to the trauma team for further investigation as appropriate, as per usual practice.

There may have been more patients with missed injuries whom the physiotherapists could not see due to the time constraints. Further, it was beyond the scope of this study to follow up on the patients to identify the incidence of any other missed injuries that were found after they were discharged from the hospital or the occurrence of chronic pain or mental health issues or delayed return to work [12]. The authors suggest that future research should incorporate follow up on post discharge missed injuries, evaluating outcomes such as functional outcomes, return to work or community activities, any continuous use of health care service and the rate of post discharge missed injury [9, 12] in a randomised controlled trial conducted over a long term to enhance generalisability of the findings, reduce the risk of bias and account for seasonal or procedural variation in trauma care. While the data presented in our study are from an earlier period, our study findings are novel and continue to hold significant relevance as MSK tertiary surveys by physiotherapists is not routine and can be used as a springboard for further longer term research.

In this study, the number of identified missed injuries may not be statistically significant between the two teams in each group, however, it can be postulated that the identified missed musculoskeletal injuries by the physiotherapists may be significant to the individual patients with the new “missed” injury such as a hand injury. Despite our study results not being statistically significant, this is clinically important in that the study demonstrates that the physiotherapists can perform MSK tertiary surveys safely and identify potentially impactful injuries in patients. To support the trauma service with a robust MSK tertiary survey to prevent any further missed musculoskeletal injuries, funded trauma specialty-specific physiotherapist/s may be needed in facilities that provide trauma services. There have been some changes in physiotherapy practice from the findings of this study. Some of the changes include modification of the ICU trauma patient handover sheet to include trauma patient's tertiary survey and further management plan. Although not formally documented in a form/guideline, Emergency Department physiotherapists have adapted their trauma initial assessment to include a MSK tertiary survey as a part of their initial assessment.

It was beyond the scope of this study to demonstrate that a trained and credentialed physiotherapy MSK tertiary survey can help reduce time to mobilisation in lieu of medical clearance. However, our results can serve as a springboard for future studies to evaluate the impact of MSK tertiary surveys in addition to the physiotherapy initial assessment on time to mobilisation, and to explore the potential benefits of earlier mobilisation in patients with trauma. Additionally, future studies should assess patient-reported outcomes and explore longer term morbidity from delayed injury recognition or missed injuries.

5 Conclusion

The value of tertiary surveys in trauma patients is well understood. However, the additional value of a MSK tertiary survey in trauma patients has not been previously studied or explored. This study demonstrated the successful implementation and feasibility of a physiotherapists’ MSK tertiary survey in identifying musculoskeletal injuries in admitted trauma patients to a busy Australian Trauma Surgery service.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and gratitude to all the volunteering physiotherapists, trauma surgery fellow, trauma clinical nurse consultants and Ken Merten Library staff at Liverpool Hospital, Sydney, Australia for their time and contribution to the study. Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley - University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The authors have nothing to report.