Illuminating nail disorders: A comprehensive overview of advanced imaging techniques

Linked article: A. Sechi et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:759–774. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.20309.

The nail apparatus is a heterogenous structure where soft and hard keratinized tissues meet over a bony phalanx. The distance between each of these structures is very small often less than a millimetre. For the non-expert, choosing the right and most informative medical imaging is difficult. This often leads to inadequate and expensive imaging. The article by Sechi et al., ‘Advances in Image-Based Diagnosis of Nail Disorders’, provides a comprehensive review of all available imaging technologies to explore the nail apparatus, X-rays excluded.1 Practical tips and tables are included to help select the appropriate imaging techniques for various nail disorders, fostering an evidence-based approach to diagnosis and treatment.

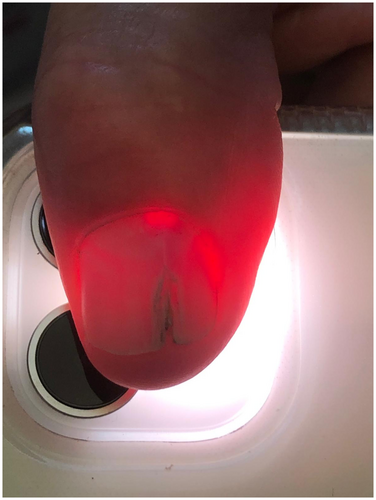

Nail unit dermoscopy magnifies nail disorders not visible with the naked eye and explores superficial structures. Its limitations are depth penetration and interpretation variability. The authors remind us of a useful trick, the smartphone flashlight fingertip transillumination, especially helpful in identifying myxoid cysts and glomus tumours2 (Figure 1).

High-frequency ultrasound (HFUS) is a widely available, non-radiating, real-time imaging technique that allows deep tissue penetration, effective for examining structures from the nail plate to the bony cortex of the distal phalanx, diagnosing and assessing and monitoring inflammatory nail diseases. It details tumour's location, size, shape, echogenicity and vascularization. It does not need the removal acrylic or prosthetic nails. HFUS is limited in detecting lesions smaller than 0.1 mm but is largely operator-dependant.

Physicians should be aware that exploring the nail unit with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has specific requirements: a dedicated coil for optimal spatial resolution is required. This device is not available in all centres. The use of other coils like wrist or knee coils are unable to provide correct images. MRI is particularly useful for detecting small or occult lesions, mostly liquid or vascular, and presurgical mapping. One of its best indications is recurrent glomus tumour, revealing a satellite lesion unnoticed during the surgery. A pilot study suggested that MRI could be proposed as preoperative imaging of squamous cell carcinoma for locoregional assessment and guide biopsy.3 Recently, MRI images could be converted into 3D models for printing, which are valuable for creating customized nail prosthetics, educating healthcare professionals and assisting in surgical planning.4

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a non-invasive imaging technique that provides high resolution of biological tissues in real-time. It is not widely available. OCT allows a penetration depth of 1–2 mm of both the nail plate and bed with a resolution of 3–15 μm. OCT helps in monitoring nail psoriasis and distinguishing between subungual haemorrhages and melanocytic lesions.

Confocal microscopy (CM) offers a near-histological resolution in grayscale images with a resolution of 2–5 μm. CM is interesting for evaluating pigmented lesions and may reduce the need for biopsies. CM has a shallow tissue penetration (up to 500 μm in nails), difficulty in visualizing hyperkeratotic changes and limited device availability. Currently, RCM is effective in identifying dermatophyte hyphae, particularly in white superficial onychomycosis, and differentiating it from true leukonychia. Intraoperatively, matrix RCM is able to assess melanocytic tumours, showing 59% sensitivity and 100% specificity in diagnosing melanonychia striata, making it a valuable preliminary screening tool, especially in paediatric patients.5

The authors rightly conclude that imaging enhances diagnostic accuracy and complement rather than replace a clinical judgement. Proper training is essential for performing and interpreting these imaging techniques. Collaboration with radiologists is the key to obtain adequate information. They believe that imaging technologies offering critical anatomical information at a reasonable cost and with global availability are likely to become the most widely used.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflicts of interests.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.