A European Public Sphere United by Football: A Comparative Quantitative Text Analysis of German, Norwegian, Polish and Spanish Football Media

Abstract

The ability of the European community to respond to the multiple crises threatening the European Union and Europe depends in part on citizens' shared European identity giving legitimacy and support to communal action. Men's elite European club football is an example of a cultural practice that is highly Europeanised, reaches diverse audiences and is a known carrier of collective identities. This article examines the emergence of a European public football sphere through the convergence of football coverage across national media spaces, serving as a foundation for European identity constructions. It connects the concept of a European public sphere to the Europeanisation and mediatisation of football and its potential effects on European identity formation. Results indicate a convergence of football coverage around high-profile and high-status aspects of European football, creating a strongly aligned, homogenous but exclusive European public football sphere that leaves many parts of Europe on the sidelines.

Introduction

Europe and the European Union (EU) are facing multiple interrelated crises, including climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, migration flows and Russia's invasion of Ukraine, which threaten peace, prosperity and social cohesion across the continent (Riddervold et al., 2021). Euroscepticism (Baldarassi et al., 2020; de Vries, 2018) and dynamics of disintegration (Leruth et al., 2019) call into question the capacity to constructively respond to these intersecting crises. Public support for the ‘European community’, partly reliant on citizens' shared European identity, is essential for high-level political co-ordination and decision-making to address collective problems.

Feelings of sameness, belonging and reciprocal trust between people of diverse socio-economic, cultural, religious or ethnic backgrounds inhabiting a shared social space, as well as experiences of contact, exchange and collaboration, create a collective identification as ‘European’ (Bergbauer, 2018). A shared identity can, in turn, provide legitimacy and increase the support for the political community and continued European integration (Fuchs, 2012; Schmidt, 2013). Various initiatives across Europe and the EU, such as Erasmus and the Eurovision Song Contest, promote economic, social, academic and cultural exchange and contribute to identity processes. However, their impact is often limited to specific social groups or citizens with higher formal education and socio-economic status (Baker, 2017; Favell, 2008; Gustafson, 2006; Salamonska and Recchi, 2019).

Men's elite European club football 1 provides an example of a cultural practice that is highly Europeanised, is a known carrier of and catalyst to collective identities and reaches diverse audiences. As such, it exposes people outside of particular social groups to Europe, creates contact with European actors and entities (e.g., players, teams and other fans), induces cross-border attention and mobility and serves as the foundation for networks of exchange and collaboration (Finger et al., 2023). Fan interactions with football are realised to a large degree through various forms of media, including live broadcasts, supplemental news and social media activities, which provide points of contact with this highly Europeanised social space. Therefore, football media plays a crucial role in shaping any potential European identity effects.

Media content shaping citizens' constructions of European identities connects to the identifying effects of converging European media spaces posited by the theory of a European public sphere (e.g., Risse, 2014). As a highly Europeanised and mediatised cultural space, football contains the potential for the emergence of a European public football sphere. This creates and perpetuates the preconditions for European identifications through football, as geographically and socially diverse audiences are exposed to European information and experiences through concurrent, topically aligned and similarly interpreted media coverage. Consequently, the specific configuration of this space in the form of actors, entities and issues represented across convergent media spaces ultimately shapes fans' opinions, attitudes and behaviours and football's potential to foster identifications at large.

We analyse the emergence of a European public football sphere through a comparative analysis of football news articles from 11 news outlets from four European countries (Germany, Norway, Poland and Spain) covering seven football seasons. Employing a dictionary-based method and supplementary analyses, we examine the extent and patterned variation of media representation of Europe across national media publics. The findings suggest a convergence of coverage in time, content and relevance around high-status aspects of European football, creating a strongly aligned, homogenous European public football sphere that leaves many parts of Europe on the sidelines. We proceed by outlining the Europeanisation and mediatisation of football and its potential effects on European identity formation by connecting it to the concept of a European public sphere (Section I), describe the design of our analysis and present the results (Sections II and III) and discuss the emergence of a European public football sphere in the broader context of European identity formation (Section IV).

I Football, European Identity and the Emergence of a European Public Football Sphere

Men's professional club football is a highly popular cultural phenomenon in Europe. As an everyday leisurely pastime that excites millions of fans, its cultural, economic and political importance surpasses that of other pop-cultural phenomena and social institutions (Cashmore and Dixon, 2016). Football permeates private and public spaces (Rowe, 2003), creates a multitude of cultural renderings (Stone, 2017) and forms collective memories and imagined communities (Anderson, 2006; Pyta, 2015). In increasingly atomised societies, football and its fandom can serve as structuring elements in the lives of many citizens (Stone, 2007). Whilst various types of fans can be differentiated (e.g., Giulianotti, 2002), we use the term ‘fan’ to encompass all those interested in football or actively engaged in football fandom.

In the past decades, football has undergone multiple intersecting transformations (Giulianotti and Numerato, 2018), most notably – for our purposes – a strong mediatisation (Skey et al., 2018) and, in Europe, a distinct Europeanisation of its governance (Niemann et al., 2021). Broadly defined, Europeanisation refers to processes of adaption and change within political, legal and social processes resulting from European integration (Featherstone and Radaelli, 2003; Schmidt, 2002). As for the Europeanisation of football governance, changes of policies and structures take place primarily within the institutional, political and legal framework of the EU but impact all members of the European football federation [Union of European Football Associations (UEFA)] owing to the interconnectedness of European football (Geeraert, 2016; Niemann et al., 2021; Parrish, 2003).

Four notable developments mark the Europeanisation of football: (1) the internationalisation of player markets following the European Court of Justice's Bosman ruling (García, 2016); (2) the establishment of a de facto pan-European league system through UEFA competitions [UEFA Champions League (CL), UEFA Europa League (EL) and UEFA Europa Conference League (ECL)] (Niemann and Brand, 2020); (3) the institutionalisation of advocacy coalitions at the European level, representing clubs (e.g., European Club Association), leagues (e.g., European Leagues) or fans (e.g., Football Supporters Europe) (Cleland et al., 2018; Mittag, 2018); and (4) regulatory efforts by the European Commission instituting certain exceptions to EU competition law for the central marketing of broadcasting rights (Andreff and Bourg, 2006; Niemann et al., 2021). These transformations resulted in the emergence of a distinctly European football sphere as an interconnected system of actors, institutions and exchange relations marked by broadly aligned administrative and regulatory frameworks, frequent games between club teams from different leagues in a European pseudo-league system, high cross-border mobility of personnel and fans, extensive media coverage and active stakeholder networks.

European Identity Formation Through Football

Along its cultural importance, football is a carrier of collective identities at various levels. Whilst its association with local and national identities is well established (e.g., Brand and Niemann, 2014; Llopis Goig, 2008; Meier et al., 2019), the Europeanisation of football has sparked research on its contribution to the formation of European identities (King, 2000; Millward, 2006; Weber, 2021). We define European identities as ‘citizens' self-categorisation as European together with their evaluations of their membership in the European collective and their affective attachment to Europe and other Europeans’ (Bergbauer, 2018). Identities are complex and processual, and their emergence and salience depend on the situational context (Ashmore et al., 2004; Jenkins, 2008), allowing national and European identities to intersect (Risse, 2015). European identities are thought to be anchored in shared values, norms and opinions (Bruter, 2003; Kantner, 2006); the identifying potential of the EU, its institutions and symbols (Calligaro, 2021; Mayer and Palmowski, 2004); or the emergence of a European public sphere (Risse, 2014) and influenced by the reception of Europe-related information and personal experiences of being part of a European community (Bergbauer, 2018; Kuhn, 2015; Verhaegen and Hooghe, 2015), as well as being discursively constructed (Eder, 2009; Mole, 2007).

Through football, fans are continually exposed to European stimuli in the form of European players, regular international matches, media coverage and broadcasts of foreign leagues, and symbols of ‘Europe’ itself (King, 2004). This ‘banal Europeanism’, where ‘subtle and subliminal identification opportunities for fans are ubiquitous’ (Weber, 2021, p. 1904), may lead to changes in perceptions, imaginations, values and, consequently, identities themselves. The interaction with football Europeanises fans' ‘frames of reference’ with which they perceive and evaluate their lifeworld and their constructions of ‘communities of belonging’ (Weber et al., 2020, p. 295). Furthermore, practices of exchange between fans (e.g., travel, communication and collaboration) create direct experiences of Europe, reinforcing European identity constructions (Finger et al., 2023; García and Zheng, 2017). With its potential for ‘social transnationalism’ (Mau, 2012) in an ‘everyday Europe’ (Favell and Recchi, 2019), football can contribute to forming European identities. Whilst it may not directly lead to (rational) support for the EU, it fosters a sense of belonging to a common cultural entity ‘from below’. Strengthening this ‘we-feeling’ amongst European citizens and their identification with Europe can address the EU's challenges and increase support for the European project (Kaina et al., 2015).

The Mediatisation of European Football

Football as a cultural phenomenon exhibits a high degree of mediatisation. This term describes a multifaceted, non-linear process of rising importance of the media and mutual adaption between media and sports that varies between contexts, such as differing degrees of mediatisation in different types of sports (Skey et al., 2018; Wenner and Billings, 2017). Football's high degree of mediatisation requires investigating fandom and its social effects through a media lens due to the ‘intricate interrelationship between sport, cultural symbols, and […] social formations’ (Hutchins and Rowe, 2012, p. 8) inherent to mediatised sports. Media coverage shapes the informational environment of fans and represents a central avenue of contact and means of interaction with football. Especially due to low-barrier-to-entry online media, information about football is ubiquitous and easily accessible (Cashmore and Dixon, 2016) and thus reaches all possible types of fans. This has been described as the ‘footballization of everyday media’ (Hagenah, 2017).

In this expansive news environment, media outlets assume a gatekeeping role between football and its fans (Bro, 2019), selecting content and framings of news coverage from a broad amount of available information based on news values – partly anticipating audience preferences. Due to these selection logics, certain, but not all, aspects of the interconnected European football system will be represented in news coverage. Still, even when covering solely domestic football, some European aspects enter reporting and discourses (e.g., concerning foreign players). Furthermore, dedicated reporting on foreign countries or the European level naturally gives considerable presence to European actors, entities and issues. Because of the interconnectedness and popularity of European football, this likely holds true across national media spheres in Europe. Media coverage of European football can consequently be a major factor in providing the information on, contact with and experiences of Europe necessary for identity formation. Mechanisms such as reinforcement by mere exposure (Bornstein and Craver-Lemley, 2017), agenda setting and framing of issues (Lecheler and de Vreese, 2018) and cultivating perceptions of social reality through media consumption (Shrum, 2017) lead to media coverage impacting fans' opinions, attitudes and behaviours, as well as their overall identity constructions.

The ‘European Public Sphere’

The presence of Europe in media spaces across national borders invokes the concept of a European public sphere, broadly defined as a shared European space of communication and debate emergent from topically segmented, overlapping and interconnected, Europeanised national public spheres (Adam, 2015; Dacheux, 2008; Nitoiu, 2013). Here, Europeanisation refers to the extent to which ‘European issues are discussed within national public spheres, and through transnational communication flows come to travel from one domestic public debate to another’ (Nitoiu, 2013, p. 33). A European public sphere does not supplant but complements national public spheres. Whilst public spheres are not necessarily limited to media discourses, the (news) media serves as an important structuring agent in their perpetuation (Heinderyckx, 2015).

Most definitions of the European public sphere revolve around media discourses on the EU and European politics (Koopmans and Statham, 2010; Risse, 2014, 2015; Rivas-de-Roca and García-Gordillo, 2022), meaning political institutions, processes and discourses at the EU level or within member countries. We extend this conception on two dimensions. First, we move beyond the ‘EU-isation’ towards a broader conception of Europeanisation, encompassing larger geographic and cultural delineations of Europe. Second, beyond the narrow focus on political news coverage, cultural or entertainment media have been highlighted for their potential to contribute to the emergence of a European public sphere (Brüggemann and Schulz-Forberg, 2009; Gripsrud, 2007).

Our conception of the European public sphere thus requires (a) a broad range of actors and issues from expressly European origins becoming incorporated into media discourses with sufficient saliency or visibility and a variety of Europeans as both speakers and audiences (Risse, 2014, 2015) and (b) a convergence of media coverage in time, content and criteria of relevance, to the extent that ‘the same transnational issues are discussed at the same time and […] with similar frames of interpretation but not necessarily with the same opinions’ (Kantner, 2014, p. 87). This can manifest as discursive connections between the national and European levels (vertical dimension) or as cross-border connections between separate national spheres (horizontal dimension) (Pfetsch and Heft, 2014). Through sufficient visibility and the convergence in time, content and criteria of relevance, separate national media spheres align into concurrent and intersecting issue publics.

Regarding European identity formation, public spheres ‘provide the communicative spaces where collective identities are actively constructed and reified’, constituting ‘the arenas where “Europe happens” and, thus, contribute to the “psychological existence” of Europe’ (Risse, 2015, p. 107). A broad range of studies confirms the effect of the reception of political news and political messaging on opinions, attitudes and identifications in the EU and broader European media spaces (Boomgaarden et al., 2010; Brosius et al., 2019; Bruter, 2003; de Vreese, 2004; de Vreese and Boomgaarden, 2016). Besides this informational dimension, constructions of identity are subliminally embedded in media discourses (Olausson, 2010), narratively naturalising and legitimising collective European identities beyond national borders (Eder, 2009). The Europeanisation of media spaces exposes audiences to European representations and normalises (mediated) contact with European actors, entities and issues. The convergence of these Europeanised spheres leads to alignment or, through cultivation, to a ‘sharing […] of views of the world […] in otherwise disparate groups’ (Shrum, 2017) across national borders. This contributes to the collective internalisation of similar narratives and frames on Europe and shapes collective European identities.

European club football and its coverage in the media as a transnational, synchronised, easily accessible and highly salient media event arguably invoke a ‘European public football sphere’ (FREE, 2015). Whilst football coverage is mostly carried by nationally based media institutions, the synchronised nature of the European match calendar means that events and developments are likely discussed at the same time across different national media spheres. Football media providing visibility to ‘Europe’ can contribute to the creation and perpetuation of imagined communities (Guschwan, 2016), create European ‘campfire’ experiences (Hagenah, 2017) and carry the political myth of the European community (Niemann and Brand, 2020). Whilst Crolley and Hand (2006) analyse football journalism for national and regional identities, we turn to the potential formation of European identities based on the emergence of a European public football sphere. Through this, diverse publics are exposed to similar European stimuli and possibly induced to develop similar attitudes, opinions and identifications towards Europe.

II Research Design

- RQ1:

How do media outlets from separate national media spaces cover European club football?

- RQ2:

Does European club football coverage from separate national media spaces converge in time, content and relevance criteria?

To analyse the criteria of visibility and the convergence of separate national media coverage around the dimensions of time, content and relevance, we employ a computer-based quantitative text analysis of selected online football news articles (Grimmer and Stewart, 2013). Using a proprietary dictionary and supplemental data, we assess the presence of Europe and the dynamics of convergence in news texts from four countries and across seven football seasons. Crucially, the scope of this study is limited to analysing the media side of the proposed identity mechanism, leaving out fans' reception and internalisation.

Operationalisation and Measurement

To measure the visibility criterion, we count matches with a multilingual dictionary (Lind et al., 2019) containing keywords for locations, persons, institutions and other entities for each UEFA member association and their national competitions (horizontal dimension) and the European level (vertical dimension), including international UEFA competitions. This distinction allows analysing the relevance of the European level and the cross-border level and connections for the respective discursive spheres. Keyword matches are aggregated into country and level (vertical and horizontal) scores and standardised for text length as the frequency of occurrence per 1000 non-stopword tokens.

Football-specific language is complex, containing names and nicknames, abbreviations and other informal descriptors. Terms can also change association over time (e.g., players transferring clubs) or have multiple associations (e.g., players associated with a club and their home country). Consequently, constructing a dictionary to match all unique identifiers is impractical. Furthermore, such a dictionary construction is susceptible to knowledge biases. To build a dictionary that is consistent and time invariant and uniquely identifies references to Europe and other European countries, we included names and descriptors of European institutions, competitions and Europe itself on the vertical dimension and (a) names and descriptors of all 55 UEFA member associations, (b) descriptors for persons from all UEFA members and (c) city names with first-division clubs in any of the selected seasons from all UEFA members on the horizontal dimension. Whilst omitting colloquialisms and most proper names, this construction applies uniform criteria to gauge European representation in the text corpus. In the analysis, cross-national comparisons are standardised to the respective country means, levelling out language-specific differences in occurrence quantity.

To analyse the convergence of separate national media spaces, we focus on the criteria of media convergence outlined above. For the temporal alignment, we aggregate the scores by publication date to assess the frequency of occurrence over time and with supplemental event data. As our method forgoes close reading of texts, we can make no statements about substantive content in the text corpus. Consequently, we approximate the issue dimension with the geographic orientation of texts by counting and comparing the occurrence of country references.

Finally, for criteria of relevance, we consider four contextual conditions that potentially determine the patterned variation of text scores between reference countries: (1) their status within the European football system, (2) the inside-out and (3) outside-in player market relationship between study and reference country and (4) their general social, economic and cultural interrelations or proximity. High-status leagues and competitions likely draw media attention due to their perceived sporting quality, competitiveness and attractiveness. Player transfers between countries, namely, foreign European players coming to a study country (outside-in) and players from the study country moving abroad (inside-out), might increase reference frequency by generating interest for the respective countries and through a desire to follow nationally relevant players playing outside the country. Finally, proximity between countries could lead to increased interest due to existing familiarity, established bilateral co-operation in other sectors, cross-border migratory movements or neighbourly sporting rivalries.

We measure these factors using the UEFA 5-year ranking, which is determined by the success of countries' clubs in continental competitions, as an approximation of relative status. Furthermore, we take the number of national team games played by nationals of our study countries based in a reference country (inside-out) and the share of players from a reference country in the respective study countries' first division (outside-in) as measures of the player market relationship between countries. Finally, direct geographic neighbourhood is used as a proxy for more general interrelations.

Case Selection, Data Collection and Pre-processing

We analyse a text corpus containing 304,434 football articles from 11 online news outlets in four countries: Germany, Norway, Poland and Spain. These countries were chosen because they represent dissimilar cases in the context of European football. They differ in terms of their international competitiveness and the internationalisation of their domestic player markets, as well as their diverse footballing traditions and fan cultures (Andersson and Hognestad, 2019; Buarque de Hollanda and Busset, 2023; Kossakowski and Besta, 2018; Llopis Goig, 2008; Sonntag, 2018). Notably, fandom in Norway is strongly oriented towards England, with double allegiances or primary fandom for English clubs, and is inherently more transnational than in the other countries (Andersson and Hognestad, 2019). Politically, the countries differ in their relationship with and public opinions on Europe and the EU, with three EU members (of different accession phases) and one non-member. Additionally, they can be contrasted by broader economic, demographic and cultural factors. Other properties, such as larger versus smaller states or population size, were considered but deemed less suitable for the intended comparison. Using this diverse set of countries allows us to identify similarities and shared dynamics between otherwise different cases and to draw broad inferences about general media logics in European football coverage. A selection of study country properties is included in Table A1.

From the selected countries, we identified online news outlets of relevance to the respective football discourse. Naturally, football media coverage extends beyond text-based online news, including social media, television and audio broadcasts. However, text-based news are crucial informational background for fans and highly relevant in the football media environment. Online sources were selected over print media for greater accessibility, broader scope and higher publication quantity. Eleven sources were both suitable per assessment by experts in the study countries and accessible by automatic web scraping. The analysed text corpus is thus constrained by technical limitations in the data selection. Still, the broad selection of general and football-specific news sources captures a relevant slice of the respective national football discourse. An overview of the selected media outlets is included in Table A2. We retrieved all available articles between July 2015 and June 2022, covering seven recent complete European club football seasons. 2

To prepare the corpus for the analysis, we constructed a keyword-based filter to remove unsuited articles. Using keyword matches in the article URL, headline, text or thematic tags, we excluded articles on other sports and other aspects of football like national teams or women's and youth football. We validated the filter by comparing a manually coded random sample of 200 articles per source with the automatic classifier. The filter mechanism is well suited for the classification, correctly identifying most retrieved articles. Detailed results of the validation effort are included in Table A3. The filtered corpus was pre-processed by removing non-letter characters and stopwords 3 and transposing all text to lower case. An overview of the numbers of available, filtered and pre-processed texts by source and over time can be found in Table A2. For the analysis of temporal alignment and relevance factors, we collected data on UEFA competitions (UEFA 5-year club ranking and event schedule), player market internationalisation (nationalities of players based in study countries) and national team appearances (number of games played for the national team).

III Results

The results show that a substantial number of analysed articles contain references to Europe, with a consistently higher occurrence of references to other European countries (horizontal) than to the European level (vertical). This is unsurprising, as coverage of continental competitions or events and developments at the European level will likely include mentions of teams, players and other actors and their countries of origin, resulting in matches on the horizontal dimension. Both dimensions are intertwined and interdependent and will be analysed jointly for temporal alignment, geographic orientation and criteria of relevance.

Temporal Alignment

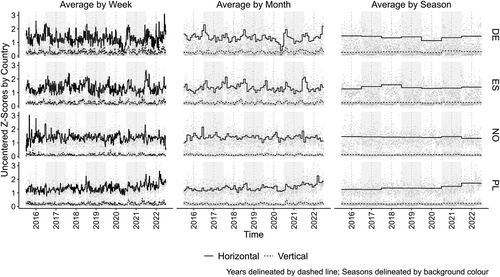

Figure 1 shows the average distribution of vertical and horizontal references by time periods, as well as by countries, for the selected time frame. Values have been scaled as uncentred Z-scores around the country mean to allow for cross-country comparisons. The text corpus exhibits variation by week, month and season over the selected time frame but shows consistent patterns over time and across countries. Week-to-week and month-to-month variations are likely a result of coverage following the general schedule of football seasons, whilst season-to-season variations are a sign of larger shifts in coverage over time. In general, the results indicate a substantial and sustained presence of both vertical and horizontal references in all study countries, all sources and over the entire time frame of the analysis. Consequently, Europe and its footballing system are consistently visible and salient in the text corpus, meaning European football is an ongoing topic of conversation and forms part of media discourses across our selected countries of study.

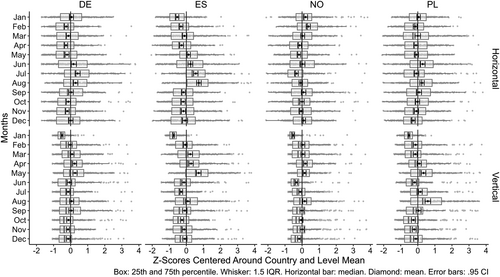

Figure 2 shows vertical and horizontal references standardised around country and level means grouped by months and by countries. This allows analysing intra-season variation of European coverage by showing deviations from the country and level mean (zero line). On the horizontal dimension, references appear to peak in the months of June and August, where Germany, Spain and Poland exhibit a higher-than-average frequency of keyword matches. Here, references to other countries are likely higher due to national team tournaments even after filtering for such articles, and with this period also being the main transfer window, coverage of player transfers will result in frequent mentions of actors and entities from foreign European countries. In Norway, the frequency of horizontal references is highest in January and February, likely because the Norwegian league pauses during the winter months. Similarly, Germany exhibits a relative peak in January, when German professional football leagues are on break. On the horizontal dimension, all countries show relatively high reference frequency in the months of March, April and May.

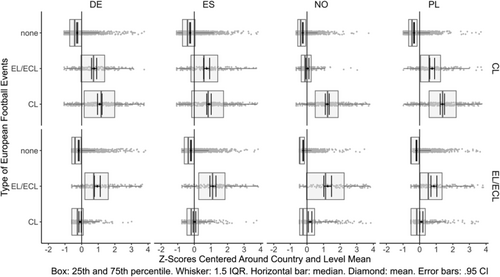

Finally, Figure 3 shows vertical and horizontal references standardised around country and level (horizontal and vertical) means by occurrence, type and stage of European football events on the day of article publication. These are games in any continental competition and group or match draws. Occurrence includes whether an event takes place on the date of publication, type differentiates by competition and stage refers to matches at the qualification, group, early knockout (Round of 32 to quarterfinals) and semi-finals or final stages. Results show that articles published on days with such events contain significantly more references on both dimensions and across all countries. Furthermore, there is a general increase in reference quantity with the rising importance of competition stages. Interestingly, days of EL and ECL matches have either significantly more or an equal number of European references as days with CL matches. This is because EL/ECL matchdays (usually Thursdays) follow directly after two CL matchdays (Tuesdays and Wednesdays) and thus include post-match coverage of CL matches. A supplementary analysis included in Appendix A confirms this (Figure A1).

Summarising the temporal analysis, the match and event calendar of continental competitions clearly shapes how media outlets across different European media spaces cover football. In all study countries, reference frequencies increase as the competitions advance, with the selected media outlets uniformly exhibiting progressively higher levels of European visibility on both dimensions. Despite the varying number of participating teams from each country and vastly different levels of success in these competitions, media discourses from all study countries seem to align vertically around the highly prestigious aspects of European football. Similarly, on the horizontal dimension, there is broad alignment around similar time periods across the study countries, presumably due to the specific structure of national football schedules or dynamics relating to national teams and transfer movements.

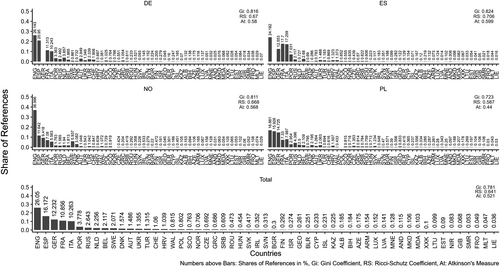

Geographic Orientation

The patterning of horizontal references serves as a proxy for the substantive content of the text corpus. Figure 4 shows the share of references each foreign country receives from each country of study and the total average. Across all study countries, England is the most referenced foreign country, with Spain, Germany, France and Italy also being referenced with relatively high frequency. Both total and individual country distributions exhibit a sharp decline in frequency after the first few countries, resulting in highly unequal distributions. On the combined scale, five countries receive more than 10% of all references each, whilst 39 countries receive less than 1% of references, nine of which fall below the 0.1% threshold. The inequality measures depicted in the figure confirm the skewed distribution of references towards a small selection of reference countries. Notably, neighbouring countries seem to receive more references, as exemplified by the Netherlands (NLD), Austria (AUT) or Switzerland (CHE) for Germany; Sweden (SWE) and Denmark (DEN) for Norway; Andorra (AND) and Portugal (POR) for Spain; and Ukraine (UKR) and Slovakia (SVK) for Poland. Still, the distribution of horizontal references is highly comparable between countries, with a small and similarly composed set of countries receiving the most references, whilst a large subset of countries is scarcely referenced. This points towards an alignment of the coverage not only on the temporal dimension but also around content as approximated by the country references in the news texts.

Criteria of Relevance

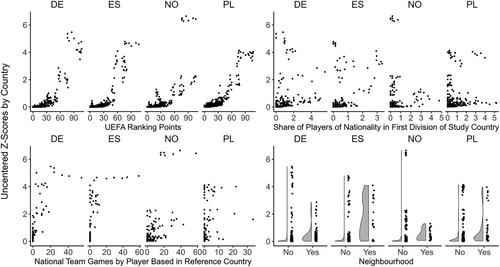

To elucidate which factors might explain the variation in country reference distribution, we aim to identify underlying criteria of relevance that lead reference countries being represented in football media discourse. We calculated multivariate regression models to examine influencing factors and assess whether the criteria of relevance align across countries. We used scores for all 1512 unique combinations of study country, reference country and season, whilst adding the UEFA 5-year ranking points (by reference country and season), the share of players from the reference country in the first division of the study country (by season), the number of national team matches played by players from the study country based in the reference country (by season) and the neighbourhood status of both countries for each case. Bivariate scatterplots of the predictor variables and the text scores are shown in Figure A2.

We calculated five mixed-effects regression models to examine the relationship between the contextual factors as independent variables (fixed effects) and reference frequency as the dependent variable. To account for the nested nature of observations (country scores in seasons), we set the season and countries (only the full model) as the grouping variables (random effects). Using these contextual factors, we fitted five linear mixed models to predict the standardised country counts. First, the models summarised in Table 1 show that when accounting for inter-season variation and the other explanatory factors, UEFA ranking points have a significant positive influence on the frequency of a reference country. Across all study countries, the more UEFA ranking points a reference country accumulated, the more it is mentioned in the text corpus. Second, national team games played by players based in a reference country have a significant positive effect in Germany, Spain and Norway. Third, foreign European players playing in the national first division are significant only in the latter two countries (at the 0.05 level). Fourth, neighbourhood to a reference country exhibits a significant effect only in Spain, where it increases reference frequency. In the full model, UEFA ranking points, domestic-based foreign players and foreign-based national team players have significant positive effects.

| Full | DE | ES | NO | PL | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI | Est | SE | DF | p | CI | Est | SE | DF | p | CI | Est | SE | DF | p | CI | Est | SE | DF | p | CI | |||||||||||

| Effect | Term | Est | SE | DF | p | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | ||||||||||||||||

| F | UEFA points | 0.03 | 0.00 | 1502.20 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 368.37 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 368.36 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 241.86 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 373.98 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| F | Fgn players | 0.08 | 0.02 | 1500.71 | <0.001 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 366.52 | 0.564 | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.06 | 367.65 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 0.39 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 372.81 | 0.024 | 0.02 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 368.22 | 0.987 | −0.06 | 0.06 |

| F | Neighbour | 0.02 | 0.05 | 1498.94 | 0.749 | −0.08 | 0.11 | −0.10 | 0.07 | 366.89 | 0.131 | −0.24 | 0.03 | 0.49 | 0.12 | 366.87 | <0.001 | 0.25 | 0.73 | −0.16 | 0.15 | 364.94 | 0.301 | −0.46 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 366.90 | 0.721 | −0.11 | 0.16 |

| F | NT games | 0.06 | 0.00 | 1505.00 | <0.001 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 372.08 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 371.35 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 372.67 | <0.001 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 368.20 | 0.178 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| R | Season | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.32 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| R | Country | 0.32 | - | - | - | - | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| R | Residual | 0.48 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.60 | 0.41 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Notes: N: Full = 1512, DE = 378, ES = 378, NO = 378, PL = 378; DF: Full = 1505, DE = 372, ES = 372, NO = 372, PL = 372; sigma: Full = 0.48, DE = 0.36, ES = 0.41, NO = 0.6, PL = 0.41; log-likelihood: Full = −1074.68, DE = −179.24, ES = −218.56, NO = −364.06, PL = −227.1; conditional R2: Full = 0.75, DE = 0.85, ES = 0.83, NO = 0.6, PL = 0.81; marginal R2: Full = 0.65, DE = 0.79, ES = 0.73, NO = 0.55, PL = 0.69.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DE, Germany; DF, degrees of freedom; ES, Spain; Est, estimate; F, fixed effect; NO, Norway; PL, Poland; R, random effect; SE, standard error.

These results indicate that in all study countries, coverage is driven by the quality of foreign football as measured by the UEFA 5-year ranking. The occurrence frequency of a reference country is strongly associated with its status within the European club football system. This factor is likely to intersect to some degree with both the inside-out and outside-in dimensions of player market internationalisation, as high-status countries are both attractive origins and destinations for player transfers. Whilst autocorrelation and collinearity tests performed for all models revealed low correlation of regression factors, they are presumably not wholly independent. Still, player market internationalisation seems more impactful in the inside-out direction, as high-profile national players playing abroad attract media attention. Outside-in player transfers and neighbourhood seem to play a subordinate role in the media coverage of European club football, as they are only significant in some of the study countries. To summarise, a convergence of separate media spaces can be seen around the ‘best’ football, with media attention, and, as a result, the frequency of references, being driven by perceived quality and status.

IV Discussion and Conclusion

The results of the analysis show that both the vertical and horizontal levels of European football are given considerable and consistent prominence across all media spaces. Whilst the overall presence of ‘Europe’ in the dataset is substantial, only a select group of countries is highly visible on the horizontal dimension, whereas others hardly appear in the discourse. In response to RQ1, the results thus show extensive, but selective, coverage of European football.

Regarding RQ2, results point towards a convergence of media coverage from the four selected countries around the dimensions of time, content and relevance criteria. Whilst situated in distinct national political, social, cultural and football-related contexts, the selected media outlets exhibit similar patterns in when, what and why they cover European football. The convergence of the time, substance and relevance dimensions indicates the emergence and perpetuation of a European public football sphere. This suggests that European football forms part of a broader European public sphere encompassing dispersed and diverse European audiences. Following the framework of banal, subconscious identity formation through exposure to European stimuli, convergence of media coverage in a European (football) sphere lays the foundation for shared European identities in fans.

Across all study countries and on both dimensions, coverage centres around high-status competitions and countries with prestigious national leagues and internationally successful clubs. These highly referenced countries also occupy an outsize economic position within European football, pointing towards the intersection of sporting status, prestige and economic success. The results mirror emergent public and academic discourses on how the Europeanisation of men's club football has deepened economic and sporting inequality (Binder and Findlay, 2012; Ramchandani et al., 2023). With both past and planned reforms of the European football system and threats of breakaway competitions (Meier et al., 2022) likely resulting in further stratification of access to and representation at the European level, the unequal visibility in football media is unlikely to change. This might limit the participation of fans from smaller or less successful countries in the shared cultural space. With only a select group of countries prominently represented, geographically or economically peripheral European countries are relegated to the media discourses' sidelines. This might accordingly influence fans' sense of (non-)belonging, leading to potentially diverging effects of the Europeanisation of football on fans on different sides of the visibility divide.

Consequently, if (mediated) contact with and exposure to Europe through football affect opinions, attitudes and values and shape European identities of fans, then exposure to this limited view will result in equally limited identifications with Europe and might undermine potentially ensuing support for the European project. Constructions of identity and belonging and networks of exchange built upon a representation of Europe that contains mostly Central-Western, highly populous, economically developed and politically influential countries will presumably be more exclusionary towards those not represented. Whilst the convergence of different media markets is a promising sign for the emergence of shared identities within a European public football sphere, its manifestation in unequal and stratified representation of Europe driven by sporting and economic disparities in European football limits the inclusivity of resulting identity formations.

The results of the analysis are naturally specific to the selected countries and media outlets. A broader country selection and examination of other forms of media, such as television, radio/podcasts and social media, would complement our analysis. As the text corpus is a convenience sample of scrapable text data, the external validity could be increased by diversifying the selection of news outlets. As the chosen time frame covers a relatively stable period in European football, changes to media coverage stemming from structural adaptions in European football are not captured. Comparing patterns and orientations of news coverage around pivotal moments would shed light on the dynamics of change. The quantitative, keyword-matching methodology chosen for this analysis could be expanded by close, qualitative reading of texts to examine substantive content or analyse discourses. The mostly geographic keyword dictionary could be extended to capture European references more precisely. Whilst we used standardised counts to level out language differences, the linguistic heterogeneity included in this sample is an obstacle that could be addressed with monolinguistic quantitative and qualitative analyses of country subsamples of the data.

Taking our analysis as a starting point, further research should focus on how fans (or certain types of fans) make sense of European football, and Europe in general, complementing the media-focused scope of this study, especially concerning the effects of the exposure to Europe through football media. On the one hand, fans' views and practices in this highly, but selectively, Europeanised cultural space are of interest, especially their interaction with other fans. On the other hand, from a more general perspective, it would be worth analysing if football fandom leads to more inclusive, open views on Europe, turning fans into ‘European citizens’. Against the backdrop of the challenges facing Europe outlined in the introduction, there is a need to approach identity in Europe from multiple angles. As an example of a highly popular and distinctly European cultural everyday pursuit, football can provide important insights.

Appendix

| Country | Football | EU and Europe | General | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| URP | Teams | PMI | Status | Support | Population | Region | |

| DE | 75.21 | 7 | 53.2% | Founding member | 51% | 83,155,000 | Central Europe |

| ES | 96.14 | 7 | 42.8% | Member (1986) | 58% | 47,398,000 | Western Europe |

| NO | 27.25 | 4 | 26.4% | Non-member | 31% | 5,391,000 | Northern Europe |

| PL | 15.88 | 4 | 37.4% | Member (2004) | 51% | 37,840,000 | Eastern Europe |

- Notes: Support: ‘Now thinking about the European Union, some say European unification should go further. Others say it has already gone too far. […] What number on the scale [1–10] best describes your position?’ – Percentage 6 and more.

- Abbreviations: DE, Germany; ES, Spain; GDP/C, GDP per capita; NO, Norway; PMI, Player Market Internationalisation (share of foreign players in the first division); PL, Poland; Teams, teams in continental competitions; URP, UEFA 5-year ranking points.

| Country | Source | Description | Season | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | 2017–2018 | 2018–2019 | 2019–2020 | 2020–2021 | 2021–2022 | ||||

| DE | spiegel.de | General-interest news website | 2708 | 2322 | 2217 | 2177 | 1918 | 1905 | 1382 | 14,629 |

| DE | sueddeutsche.de | General-interest news website | 927 | 1118 | 929 | 909 | 946 | 970 | 640 | 6439 |

| DE | welt.de | General-interest news website | 2763 | 2298 | 1951 | 1684 | 1350 | 1168 | 1029 | 12,243 |

| ES | abc.es | General-interest news website | 1104 | 2013 | 2831 | 2765 | 2578 | 2362 | 1553 | 15,206 |

| ES | elpais.com | General-interest news website | 3297 | 3319 | 3450 | 2684 | 2190 | 2461 | 2100 | 19,501 |

| ES | marca.com | Sports news website | 21,324 | 13,441 | 11,664 | 8951 | 8508 | 7965 | 9314 | 81,167 |

| NO | nettavisen.no | General-interest news website | 1682 | 5956 | 7396 | 8776 | 7648 | 10,678 | 9879 | 52,015 |

| NO | nrk.no | General-interest news website (public broadcaster) | 1735 | 1735 | 1511 | 993 | 787 | 4676 | 1767 | 13,204 |

| PL | rzeczpospolita.pl | General-interest news website | 578 | 547 | 914 | 1191 | 919 | 986 | 553 | 5688 |

| PL | sport.pl | Sports news website | 2398 | 3479 | 5904 | 7042 | 7308 | 7836 | 8953 | 42,920 |

| PL | weszlo.com | Sports news website | 4464 | 4797 | 4513 | 4951 | 4911 | 7410 | 10,376 | 41,422 |

| Total | - | - | 42,980 | 41,025 | 43,280 | 42,123 | 39,063 | 48,417 | 47,546 | 304,434 |

- Notes: Totals presented are post filtering.

| Source | Test statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | Sensitivity | Specificity | Precision | Recall | F1 | |

| spiegel.de | 0.68 | 0.98 | 0.89 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.96 |

| sueddeutsche.de | 0.65 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| welt.de | 0.73 | 0.96 | 0.80 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.94 |

| abc.es | 0.65 | 0.96 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| elpais.com | 0.46 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| marca.com | 0.78 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.97 |

| nettavisen.no | 0.76 | 0.92 | 0.76 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| nrk.no | 0.21 | 0.79 | 0.94 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 |

| rzeczpospolita.pl | 0.70 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.91 |

| sport.pl | 0.72 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.96 |

| weszlo.com | 0.61 | 0.95 | 0.83 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.92 |

- Notes: Values are calculated from comparing 200 automatically classified documents with a manually coded blind sample. Prevalence: proportion with attribute (articles on men's elite European club football). Sensitivity: true positive rate. Specificity: true negative rate. Precision: proportion of true positives amongst all positives. Recall: proportion of true positives amongst all actual positives. F1 score: harmonic mean of precision and recall.

Figure A1 shows references to European competitions (CL, top; EL and ECL, bottom) by whether a certain type of football event takes place on a specific day: ‘none’ means no event on the horizontal level takes place, ‘EL/ECL’ denotes events in secondary competitions taking place and ‘CL’ indicates a high-level event taking place. The plot facets show references to each level. The results show that there is a high level of references to the CL even on days when EL/ECL matches occur. Conversely, on days of CL matches, there is very little attention towards EL/ECL. This confirms the hypothesis that CL coverage extends beyond only the matchdays to include the following days (usually EL/ECL matchdays).

Open Research

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data Availability Statement

Data and code are available at https://osf.io/bpqgk.

References

- 1 Whilst other facets of the game, such as national team football, women's football and youth football, are important, throughout this article, ‘football’ refers to men's elite European club football.

- 2 In three of the four study countries and at the European level, football seasons run from July to June of the following year. In Norway, the domestic season is played by calendar years. In 2020, the European and domestic football schedules were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

- 3 For German, Norwegian and Spanish texts, we used the R package ‘stopwords’. For Polish texts, we used the collection of stopwords from https://github.com/bieli/stopwords.