Young EFL Learners’ Incidental Collocation Learning Through Different Multimodal Inputs: A Mixed-Methods Study

Funding: This study was supported by the University of Bristol PhD Scholarship.

ABSTRACT

enThis study explores how multimodal input modes affect young EFL learners’ incidental collocation learning performance and experience. A total of 97 EFL learners (aged 12–13) in a Chinese secondary school were randomly assigned to two multimodal groups (reading-while-listening and viewing-with-captions) and a reading-only group (as a control group). The results revealed that both multimodal conditions positively contributed to incidental collocation gains at both recognition and recall levels. Although the two multimodal input types did not differ significantly in their effects on recognition knowledge, the viewing-with-captions mode showed a statistically significant effect on recall knowledge. However, collocation learning gains in form recognition and meaning recall decayed considerably within two weeks across all three input modes. Despite the decay, students in the multimodal conditions still outperformed in receptive knowledge of target collocations and reported more enjoyable learning experiences and better comprehension of both content and the unknown collocations.

摘要

zh本研究旨在探讨不同的“多模态学习环境” (reading-while-listening, RWL, and viewing-with-captions, VWC) 对英语学习者“偶然习得英语搭配词组” (incidental learning of collocations) 表现与体验的影响。97名中国初中英语学习者参与了本研究, 并被随机分配至三个小组:以下两组多模态输入组和一组对照组:RWL组、VWC组和对照组。研究结果表明, 两种多模态输入方式学习环境均在识别搭配形式与回忆搭配意义两个层面显著促进了学习者的学习结果。尽管两种多模态学习环境在提升识别搭配形式方面无显著差异, VWC组在回忆词组意义方面的表现显著优于RWL组。然而, 在所有学习环境下, 学习者在识别形式与回忆意义方面的习得效果均在两周后出现了显著下降。尽管存在衰减现象, 多模态组的学习者在识别形式层面上的表现仍优于对照组, 并在主观反馈中表现出更高的学习愉悦度和对学习内容及未知搭配的更好理解。综合来看, 本研究结果支持在初中EFL教学中引入多模态词汇学习环境, 以提升学生的词汇搭配习得效果与学习体验。

1 Introduction

English collocations are so frequent that they form the foundation of language learning and use, accounting for one-third of all discourse (Nation 2013). The better mastery of collocations can then enhance learners’ text comprehension. However, acquiring collocations poses a significant challenge for second language (L2) or English as a foreign language (EFL) learners (Peters 2016), particularly for young learners (Cameron 2001). Two main factors found to contribute to this challenge are limited exposure and a conventional focus on single-word instruction. First, young EFL learners often encounter limited exposure to collocations both inside and outside the classroom. While explicit instruction in class can support collocation learning, classroom input alone is typically insufficient for full mastery. To develop a robust mastery of collocation knowledge, learners need ongoing, incidental exposure beyond the classroom environment (Teng 2022). Second, English instruction in many EFL settings has traditionally emphasized single-word items over multi-word expressions like collocations. The lack of instructional focus, coupled with limited classroom time, seems to limit young English students’ opportunities to acquire collocations effectively. As a result, young EFL learners in China, along with those in other comparable educational and cultural contexts, need to seek additional support outside the classroom to enhance their collocation knowledge.

Incidental vocabulary learning through different kinds of meaning-focused input is regarded as one of the most effective approaches to complement intentional classroom learning (Nation 2013). Numerous studies in the applied linguistics field have pointed out that as a by-product of meaning-focused activities (Ellis 1999), such as reading a novel, incidental vocabulary learning can increase learners’ vocabulary for long-term growth both inside and outside the classroom. Thanks to technology and multimedia, language learners nowadays have increasing opportunities to access a diverse range of reading materials and acquire collocations. These materials are no longer limited to text-only but encompass various multimedia formats, including audio and video. Mayer's multimedia learning hypothesis (2020) supports the positive effects of these multimodal learning materials, suggesting that learners achieve better learning outcomes when two channels of language input are offered at the same time, such as text, image, sound, and video. These diverse channels, referred to as input modalities (Mayer 2020), enhance learning comprehension and retention by integrating multiple sensory modes (e.g., textual, pictorial, auditory, or audiovisual) into communicative activities (Pellicer-Sánchez 2022). With this theoretical foundation, learners can establish more robust referential connections and decode unfamiliar word items under the concurrent input conditions (Mayer 2020). Over the past two decades, empirical studies (e.g., Webb and Chang 2012; Teng 2023) on young EFL learners confirmed the positive effects of multimodal meaning-focused input on L2 single words learning, particularly focusing on reading with auditory support and viewing with on-screen captions (i.e., a stream of written text displayed on-screen in synchronization with the audio content). The findings have suggested that audio can help young learners to build closer links between spoken and written forms of lexical items, which further enhances memory (Webb and Chang 2012). Similarly, captions can reduce young learners’ decoding load, thereby enabling them to identify unknown lexical items’ forms and interpret meanings from viewing (Teng 2023).

However, to our knowledge, no studies have specifically focused on young EFL learners’ incidental collocation learning by comparing the two input conditions, that is, reading-while-listening and viewing with captions. This inquiry is important because, theoretically, Mayer's (2020) redundancy principle suggests that duplicating and repeating information in the same channel will increase cognitive load and split students’ attention which will not facilitate learning. This raised a further question of whether increasing amounts of information from added input channels become redundant and cause cognitive overload in young learners and hinder their collocation development. Pedagogically, research into incidental collocation learning for young learners with different multimodal input can guide L2 teachers to select appropriate teaching materials inside and outside the class and provide evidence for explicit classroom collocation instruction to pay more attention to those multi-word items that have not been mastered after incidental learning through meaning-focused multimodal input (Webb and Chang 2022).

The present study aims to compare young EFL learners’ collocation learning from two different multimodal inputs versus a single input as a control group and to understand their perceptions and learning experiences after engaging with different multimodal conditions. The results are anticipated to offer insights into how different types of multimodal input are used to enhance young EFL learners’ collocation learning gains.

2 Literature Review

Adopting a frequency-based perspective, this study defines collocations as two-word combinations that co-occur in a corpus with greater statistical likelihood than would be expected by chance (Webb et al. 2013), regardless of their semantic connections or level of compositionality (Gablasova et al. 2017). Collocations’ statistical strength of co-occurrence can be quantified by mutual information (MI) scores. MI scores can be calculated by the likelihood that two words appear together within a specified span of text in a corpus (Hunston 2002). This study adopts the frequency-based approach for two primary reasons. First, unlike the phraseological approach (e.g., Howarth 1998), which depends on subjective judgment about the semantic relationship and the level of compositionality of collocations, the MI scores yielded from the frequency-based approach offer researchers an objective measure for identifying collocations because higher MI scores (e.g., over 3.0) indicate stronger associations between the two words (Boers and Webb 2018). Second, frequency of occurrence is a crucial factor when choosing collocations for language learning. This corpus-based approach highlights lexical items that learners are likely to encounter frequently in real-word language use, ensuring more effective collocation selection (Nation 2016).

2.1 Theoretical Foundations for Multimodal Collocation Learning

Mayer's (2020) cognitive theory of multimedia learning emphasizes that human cognition involves separate channels, namely visual and auditory channels, for processing visual and verbal information. When learners process both image and text information simultaneously, both channels are activated, thereby enhancing learning outcomes. As Mayer asserts, this cognitive process improves learning outcomes, making learning from the combination of text and other input modes (i.e., audio, image, and video) more effective than learning from text alone. This claim aligns with the dual coding theory (Paivio 2006), which also posits that human cognition consists of two distinct but interconnected systems, namely verbal and non-verbal systems. When both systems are engaged at the same time, memory is enhanced.

More specifically, two principles of Mayer's (2020) multimodal learning theory are particularly relevant to input modes. First, the modality principle suggests that delivering information through the same channel, such as the simultaneous presentation of graphics and text, may overload the visual channel (Moreno and Mayer 1999). In contrast, delivering information across different channels can better convey information, for example, reading-while-listening or videos with audio and captions. Second, the redundancy principle emphasizes that providing the same information through multiple formats can hinder rather than facilitate learning. For instance, watching videos with captions may be less effective than watching videos without captions (Niegeman and Heidig 2012) because some learners may find it redundant to read the on-screen text while simultaneously processing the same audiovisual content. Redundant input, especially when the same information is repeated across different visual formats, can strain memory and impede learning (Moreno and Mayer 1999). Together, presenting the same content within the same channel or through multiple formats might increase cognitive load and interfere with learning. It is important to note that these two principles were primarily developed in the context of L1 content learning, while their effects on L2 learning require continued investigations.

2.2 Multimodal Collocation Learning in Adult Learners

Empirical studies on multimedia input modes for L2 adult learners’ incidental collocation learning have yielded mixed findings in relation to Mayer's (2020) multimedia learning theory.

Webb and Chang (2022) compared the effects of reading-only, listening-only and reading-while-listening on two aspects of collocation knowledge (i.e., form recognition and meaning recall) of 112 Chinese EFL students at the university level. The results showed that students in the reading-while-listening group (28%) achieved the highest scores in both immediate and delayed post-tests. Similarly, Vu et al. (2023) found that reading-while-listening led to significantly greater learning gains than reading-only among 100 pre-intermediate Vietnamese EFL learners exposed to 32 target collocations. These findings support the modality principle, suggesting that dual-channel input (i.e., both visual and auditory) can enhance L2 collocation learning. Conversely, against the redundancy principle, previous studies almost reached a consensus that captioned audiovisual input led to greater learning in multiword units (e.g., Majuddin et al. 2021; Montero Perez et al. 2014). Captioned videos provide additional information through synchronized visual and auditory input, enabling learners to perceive the form, pronunciation, and contextual use of collocations more effectively.

More recently, SLA researchers have focused on exploring how two different types of multimodal learning conditions, such as reading-while-listening and viewing with captions, influence L2 incidental collocation learning. Dang et al. (2022) conducted a large-scale study of 165 postgraduate Chinese students and assessed their receptive knowledge of 19 target collocations through multiple-choice tests immediately and one week after treatment. The results found that participants in the viewing with captions group performed significantly better than their counterparts in the reading-while-listening group. On the other hand, Vu et al. (2023) designed a longitudinal study over four weeks with 80 Vietnamese university students. Participants were randomly divided into reading-while-listening, viewing with captions, or control groups. The results found no statistically significant difference between the two experimental groups. Importantly, these studies assessed only specific aspects of collocation knowledge, such as form recall or meaning recognition, making it difficult to determine the overall effectiveness of each modality (Nation 2013). Furthermore, Pu et al. (2024) suggested that viewing with captions was more beneficial for adult learners to gain productive collocation knowledge, compared to reading-while-listening, whereas no significant difference was observed for receptive collocation knowledge between different multimodal conditions.

Due to limited empirical evidence and mixed findings, it remains inconclusive whether viewing captioned videos and reading-while-listening nurture adult EFL learners’ collocation gains or whether such findings can be generalized to other EFL age groups.

2.3 Multimodal Vocabulary Learning in Young Learners

Compared to the empirical evidence on adult EFL learners (e.g., Dang et al. 2022; Vu et al. 2023; Pu et al. 2024), research on young learners’ incidental L2 collocation acquisition through different multimodal input is extremely scarce. Given the scope of the present study, empirical research on incidental vocabulary learning focusing on enhancing young learners’ attention through various methods, such as text enhancement or pre-teaching is not included. Over the past 15 years, four studies (e.g., Webb and Chang 2012; Jelani and Boers 2018; Peters 2019; Teng 2023) have closely examined the effects of various forms of multimodal input on incidental vocabulary learning among young learner groups, albeit focusing solely on L2 single-word items.

Webb and Chang (2012) conducted a longitudinal study to investigate the vocabulary learning gains of 15-16-year-old EFL learners. Eighty-two learners engaged with 28 beginner-level short texts through reading or combined reading and listening over 28 weeks. Differences in their learning of form and meaning knowledge of 50 target words after the treatment period were assessed using a self-check vocabulary knowledge scale. The study found that young learners made significantly greater improvement in vocabulary knowledge when engaging in reading-while-listening activities. These findings support the modality principle by demonstrating the positive effects of combining visual and auditory input for young EFL learners.

On the other hand, Jelani and Boers (2018) compared incidental vocabulary uptake through two multimodal conditions: captioned and uncaptioned viewing. Eighty-one 16-year-old EFL students watched the same short video (10 min) either with or without captions. Immediate post vocabulary tests examining both form and meaning knowledge were administered to assess the extent of learning gains of 15 target words. While the results indicated that captions were more beneficial for participants’ meaning recall knowledge, captions did not matter much in the form tasks. Against the redundancy principle, this suggests that presenting the repeated information in the same channel (i.e., graphics and captions) seems to enhance productive vocabulary learning without overloading cognitive capacity.

Following this line of findings, Peters (2019) recruited 142 EFL students (Mage = 16.4) from a secondary school in the Netherlands and let them watch the same documentary under one of three multimodal conditions: with captions, with L1 subtitles, and without captions or subtitles. Thirty-six words were selected as target items and consisted of the immediate post vocabulary test items. The scores indicated that teenagers in the captioned group gained the most vocabulary knowledge in both form recognition and meaning recall tasks, more than those who were exposed to L1 subtitles or did not see any on-screen text. Peters’ findings further supported the positive effect of captioned viewing on both receptive and productive knowledge of words and echoed those of Jelani and Boer's (2018) study that captioned viewing had a positive effect on the productive aspect of word knowledge.

Recently, Teng (2023) compared how learning happened in captioned and uncaptioned audiovisual modes on young EFL learners’ incidental vocabulary acquisition. A total of 101 EFL learners aged 11–13 from a primary school in China were assigned to one or the other of the conditions and watched the same storytelling video. Both form recognition and meaning recall tests of 35 target words were carried out both immediately and two weeks after the treatment. Results supported that captioned audiovisual input was beneficial for vocabulary acquisition in both form and meaning knowledge. The superiority of the captioned group in learning outcomes at the form level was also demonstrated two weeks later. These findings further support the beneficial role of captions in young learners’ vocabulary development, in line with Peters (2019).

Although these studies offer valuable insights into young EFL learners’ incidental single-word vocabulary learning through multimodal input, none specifically addressed collocation learning under different multimodal conditions. Given that young learners may exhibit different cognitive and linguistic processing patterns compared to adults, findings from adult studies cannot be directly generalized to younger populations. To better understand how young EFL learners acquire collocations through multimodal input, it is crucial to compare reading-while-listening and viewing with captions directly.

3 The Present Study

- RQ1. To what extent do young EFL learners’ performances in incidental collocation tests vary across three learning modes?

- RQ2. To what extent does performance change over time within each of the three learning modes?

- RQ3. What are young EFL learners’ learning experiences when engaging in three learning modes?

4 Methods

4.1 Participants

Convenience sampling was employed and thus 97 Grade 7 students (49 girls, 48 boys) aged 12–13 were drawn from three intact classes at a secondary school in China. Each intact class was treated as a unit and randomly assigned to one of three groups: reading-while-listening (RWL, N = 32), viewing with captions (VWC, N = 33), or reading-only (RO, N = 32). They were taught by the same teacher with seven years of teaching experience and learned from the same material at school.

Chinese is the participants’ first language, and English is a compulsory subject taught at this school. During the study, they had an average of 6.5 years of English learning experience, and their proficiency was an average of the A2 level in the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. Their prior vocabulary size was assessed through Meara and Milton's (2003) X-Lex vocabulary size test because this test suits low-proficiency learners and requires low cognitive demands for completion. Results showed that participants’ prior vocabulary-size mean was between 1000 and 2000-word families (M = 1371, 95 CI [1195, 1945], SD = 435). The final analysis excluded four students’ data due to their absence from the delayed post-tests or failure to complete the reading comprehension test. Consequently, 93 participants (RWL, N = 31; VWC, N = 31; RO, N = 31) were included in the data analysis.

4.2 Material

An excerpt from an authentic English storytelling video from English Language Teaching was selected. The episode lasted for approximately 20 min, and the episode's script contained 2049 words, resulting in a speech rate of 100 words per minute. This rate was slightly lower than the average speech rate of graded readers (113 wpm) (Pellicer-Sánchez et al. 2020), ensuring that young participants had sufficient time to engage with the whole material. Using Compleat Lexical Tutor (Version 8) to check the script, 98.8% of the words belonged to the first 1,000-word family and 96.3% belonged to the first 2,000 most frequent words, and readability ranged from 7 to 8. Together, these values indicate that the vocabulary thresholds (98% coverage) necessary to comprehend the materials aligned well with participants’ prior vocabulary size (Hu and Nation 2000).

For participants assigned to the VWC group, the material was presented via a video format alongside English captions displayed at the bottom of the screen. The script of the video served as material for both the RWL and RO groups, differing only in the absence or inclusion of auditory support. The written text was presented across 10 pages on screen (an average of 200 words per page) to the RWL and RO participants. The on-screen texts were formatted in 18-point Times New Roman with double line spacing. Based on the speech rate of the audio, each page was displayed for approximately two minutes. In the RWL group, the screen advanced automatically when the audio for each page ended. In the RO group, each page was similarly displayed for 2 min and advanced automatically.

4.3 Target Collocations

A total of ten collocations were selected and served as target (N = 5) and control (N = 5) collocations in the study (see S1 in the Supplementary Materials). Their mutual information (MI) scores were examined via the British National Corpus (BNC) (https://www.english-corpora.org/bnc/), which confirmed that all of them reached scores over 3.0. Among these collocations, five were selected as the target collocations for two reasons. First, all of them were repeated three times in the material, meeting Webb et al.’s (Webb et al. 2013) criteria that repeated exposure of target items enhances incidental vocabulary learning. Second, these five collocations included one word from the top 2,000 most common words in the BNC, paired with another from the 3,000-to-8,000-word range. Another set of five collocations consisted entirely of single words that belong to the top 2,000 high-frequency words in the BNC. These were chosen as control collocations to minimize test effects (Peters 2019).

4.4 Measures

Participants’ learning outcomes were measured by vocabulary tests and learning experience by one-on-one interviews. To ensure the participants’ baseline understanding of the material, a reading comprehension test containing 10 true/false questions (see S2 in the Supplementary Materials) was administered after the treatment and before immediate vocabulary tests (e.g., Dang et al. 2022). To control learners’ prior target collocation knowledge and avoid possible guessing in post and delayed post vocabulary tests, a pre-test was also administered, and learning gains were calculated based on relative learning rate (see Scoring and Analyses). The one-on-one semi-structured interviews required the participants to reflect on how they had engaged in one of the multimodal conditions.

4.4.1 Vocabulary Tests

The present study considered test variety (Nation 2013) when designing collocation knowledge tests. Two aspects of collocation knowledge (i.e., form recognition and meaning recall) were measured in paper-and-pencil tests. To reduce the potential test effects (Peters 2019) and the frequency of encountering the target words, we combined form recognition and meaning recall into one integrated test in pre, post, and delayed post-tests with different item orders. Following Read's (2019) instruction, a multiple-choice format was adopted to measure the receptive knowledge of collocations, while a free production task was administered to measure the productive collocation knowledge.

The first section of the vocabulary test evaluated participants’ ability to identify target collocations when presented with their forms through both written and listening formats or written alone. Participants were asked to select the correct spelling of low-frequency words that were contained in the target collocations and appeared in the material. Each test item presented five options: one correct response, three distractors, and an “I don't know” option to discourage random guessing. The distractors matched the correct answer in word class and frequency in the BNC and were semantically linked to the story to appear plausible (Pellicer-Sánchez et al. 2022). The second section examined participants’ ability to produce the meaning of the target collocations following exposure in different input modes. Participants were instructed to write down all known meaning senses as either L1 translations or L2 synonyms/definitions.

The vocabulary test in all three timings proceeded as follows (see S3 in the Supplementary Materials). First, participants were presented with the aural and written form (or only written form) of each test item, with five options. Second, they selected what they considered to be the correct form that they had heard and seen (or only seen) in the material. Third, they wrote down the meaning of the whole collocation based on their selection. The order of the test items varied across the pre, post, and delayed post-tests to reduce the likelihood of memorization or order effects.

4.4.2 Interviews

Interviews further explored the participants’ collocation learning experience in different learning modes. Participants from all three groups were invited to participate in individual, semi-structured interviews. To ensure content validity, the interview questions were reviewed and tweaked by a colleague specializing in language teaching. All interviews followed the same prompts (see S4 in Supplementary Materials), with additional follow-up questions posed as needed for clarification or illustration. Each interview lasted for approximately 30 min and was audio recorded. Given the participants’ English proficiency, the interviews were conducted in Chinese, their native language, to encourage them to elaborate as much detail as possible.

4.5 Procedures

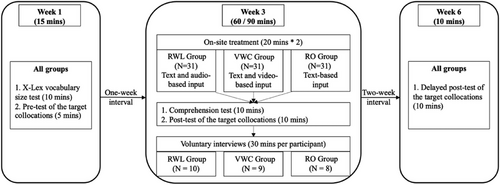

Prior to the research, the teacher informed the participants and their parents about the purpose of the research and obtained their consent. Figure 1 illustrates the data collection procedure.

Data were collected from three intact classes using four spare periods following formal classes at school over six weeks. In the first week, participants took an X-Lex vocabulary size test and the pre-test of the target collocations. One week later, participants accepted the treatment in different learning conditions. They either read, listened to, or watched the material twice, and completed a comprehension test immediately after the treatment, followed by the post target collocation test. Subsequently, a total of 27 students voluntarily participated in the interview: ten from the RWL group, nine from the VWC group, and eight from the RO group, reaching data saturation (Braun and Clarke 2021). Two weeks later, participants completed the delayed post-test on target collocations.

4.6 Scoring and Analyses

Participants’ responses to form recognition and meaning recall were marked and analyzed separately in all tests due to distinct aspects of collocation knowledge. For form recognition, one point was awarded for each correct selection. For meaning recall, answers that accurately conveyed the meaning in L1 and/or offered close paraphrases, synonyms, or explanations in L2 received one point. To ensure consistency in scoring, the first author and the participants’ teacher discussed and listed all possible answers before independently scoring the tests. The second author reviewed all scoring results and calculated the scores for each test. Any discrepancies were addressed through discussion and resolved by reaching a mutual agreement.

To mitigate the influence of guessing in the pre-test, relative learning gains were calculated in place of raw scores, using the formula proposed by Webb and Chang (2015: 675): [(correct actual post-test score—pre-test score) / (total words tested—pre-test score)] * 100. The same formula was applied to the delayed post-test scores.

To address RQ1 and RQ2, a one-way ANOVA was first conducted to examine differences in relative collocation learning gains across the three input conditions, followed by Bonferroni post hoc comparisons. Then, paired-sample t tests were used within each input mode to determine whether relative gains in form recognition and meaning recall were maintained from the immediate to the delayed post-test. For all t-tests, L2-specific effect sizes (Cohen's d) were employed, where values of .40, .70, and 1.00 indicate small, medium, and large effects, respectively (Plonsky and Oswald 2014). To answer RQ3, interview data were elicited using inductive thematic analysis, following Braun and Clarke's (2006): reading the entire data set, highlighting the initial codes, summarizing the potential themes, refining and defining the themes, and writing the findings. The first and second authors coded the data separately, achieving good reliability according to Cohen's kappa value.

5 Results

RQ1 Immediate Incidental Collocation Performances Across Three Learning Modes

Descriptive statistics for relative gains in form recognition and meaning recall at post-test and delayed post-test are shown in Table 1 (see S5 in Supplementary Materials for the raw scores). Overall, young EFL learners showed an increase in the mean relative collocation learning rate for form recognition and meaning recall from the pre-test to the post-test across all input conditions. However, these improvements appeared to decline in the delayed post-test scores.

| Input mode | Form recognition | Meaning recall | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Post-test M (SD) |

Delayed post-test M (SD) |

Post-test M (SD) |

Delayed post-test M (SD) |

|

| RO (N = 31) | 29.35 (34.15) | 13.49 (30.65) | 1.29 (5.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| RWL (N = 31) | 52.15 (27.58) | 22.74 (30.65) | 1.29 (5.00) | 1.29 (7.18) |

| VWC (N = 31) | 56.45 (27.66) | 34.09 (39.65) | 9.68 (15.38) | 1.94 (7.92) |

A one-way ANOVA was performed to compare whether the participants’ learning gains differed significantly across the three input modes. Pairwise comparisons across the three groups are shown in Table 2.

| Comparisons | Form recognition | Meaning recall | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Post-test MD |

Delayed post-test MD |

Post-test MD |

Delayed post-test MD |

|

| RO-RWL | −22.80* (p = 0.011) | −9.25 (p = 0.938) | 0.00 (p = 1.00) | −1.29 (p = 1.00) |

| RO-VWC | −27.10** (p = 0.002) | −20.59 (p = 0.078) | −8.39** (p = 0.003) | −1.94 (p = 0.661) |

| RWL-VWC | −4.30 (p = 1.00) | −11.34 (p = 0.648) | −8.39** (p = 0.003) | −0.65 (p = 1.00) |

- MD = mean difference; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

For the post-test learning gains, there was a significant difference in both form recognition (F (2, 90) = 7.33, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.14) and meaning recall (F (2, 90) = 7.61, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.15), with large effect sizes. Post hoc analysis using Bonferroni adjustment further indicated significant differences in form recognition between the RWL and RO groups (p = 0.011), and between the VWC and RO groups (p = 0.002), but not between the two multimodal groups (RWL and VWC). In meaning recall, significant differences were found between the VWC and RO groups (p = 0.003) and the VWC and RWL groups (p = 0.003), but with no significant difference between the RWL and RO groups.

For the delayed post-test learning gains, the three input modes showed no significant differences in either form recognition (F (2, 90) = 2.57, p = 0.082) or meaning recall knowledge (F (2, 90) = 0.79, p = 0.457).

RQ2 Delayed Incidental Collocation Performances Within Each Learning Mode

Table 3 shows the results of paired-sample t tests, indicating overall learning decay in both form recognition and meaning recall, respectively, for the three groups, from the post-test to the delayed post-test.

| Input mode |

Form recognition (delayed post—post) |

Meaning recall (delayed post—post) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD (SD) | t | p | d | MD (SD) | t | p | d | |

| RO (N = 31) | −15.86 (31.10) | 2.840 | 0.008 | 0.51 | −1.29 (5.00) | 1.438 | 0.161 | 0.26 |

| RWL (N = 31) | −29.40 (37.54) | 4.361 | < 0.001 | 0.78 | 0.00 (8.94) | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.00 |

| VWC (N = 31) | −22.37 (52.15) | 2.388 | 0.023 | 0.43 | −7.74 (13.34) | 3.230 | 0.003 | 0.58 |

The three groups showed significant decay in their form recognition learning rate from the post to delayed post-test. For the decay in meaning recall knowledge, a statistical difference was only observed in the VWC group. However, the reader should interpret this result with caution. In the RO group, the non-significant decay was mainly due to learners’ low learning gains in the post-test. In the RWL group, the delayed post-test scores for meaning recall remained the same as the post-test scores. These particular instances led to non-significant differences in meaning recall scores between the post-test and delayed post-test in both the RO and RWL groups.

RQ3 Learning Experiences Across Three Learning Modes

Three main themes emerged from the qualitative data and are presented below. Participants’ quotes were anonymized using a group-number format, for example, RWL-02.

‘I felt like the audio was guiding me through the story when I read it… I like listening to the different voices from different characters’. (RWL-07)

‘I quite enjoyed watching this video because it made the story come to life … and subtitles helped me follow along more easily’. (VWC-04)

‘I felt that sometimes it was a bit difficult and boring while paying all my … effort and attention to this story’. (RO-09)

‘Sometimes the intonation shows the character's emotions … they sound excited, sad, or even scared. When I hear the emotions in the story, I could understand what's really happening’. (RWL-01)

‘In the video, I could see the characters, places and actions. This helped me know what's going on without having to too much guess on the words I didn't know’. (VWC-08)

‘I found it difficult to understand such long reading materials just by reading them silently on my own … because I easily forget the previous content’. (RO-01)

‘The voices helped me know how words are supposed to sound together in a sentence. If I came across a word phrase I did not know, I heard the voices, so I know how to say them’. (RWL-03)

‘When I heard something that I don't know, I read the words on the screen and used the animation to guess the meaning. Most of the time, I think my guesses were correct or … uh … very close’. (VWC-07)

‘When reading alone, the words look piled up … and it's exhausting to read and finish the whole story. I don't even get to learn something new because I usually just skip unfamiliar words’. (RO-07)

6 Discussion

The present study investigated the effects of the three input modes (reading-only, reading-while-listening, and viewing with captions) on young EFL learners’ incidental collocation learning and explored their experiences with these learning modes.

6.1 Immediate Collocation Learning Gains and Perceptions Across Three Learning Modes

In response to relative learning gains of target collocations immediately after the treatment, the present study found that while young EFL learners could gain collocation knowledge in all three input modes, those learning in multimodal conditions, either in reading-while-listening or viewing with captioned videos, outperformed those in the reading-only group in terms of both form recognition and meaning recall knowledge. These results support the findings of previous studies on adult EFL learners’ incidental collocation learning (Webb and Chang 2022; Pu et al. 2024) and provide empirical evidence to support Mayer's (2020) multimedia learning theory that more than two input modes stimulating visual and auditory channels at the same time do not distract learners’ attention.

For form recognition knowledge, significant differences were found between the RWL and RO, as well as the VWC and RO, suggesting that both multimodal conditions facilitated more effective recognition of the forms of the target collocations compared to unimodal input (RO). The present findings echo Vu et al. (2023) and Pu et al.’s (Pu et al. 2024) studies that two different multimodal learning conditions (i.e., reading-while-listening and viewing with captions) contributed similarly to the development of receptive collocation knowledge. However, the results only partially align with those reported by Dang et al. (2022), showing that viewing with captions had a significantly positive effect on the acquisition of receptive collocation knowledge for adult EFL learners, but reading-while-listening learning condition yielded no statistical improvement in receptive collocation knowledge compared to reading-only modes. One possible explanation for these inconsistent results is that Dang et al. (2022) focused on university students learning unknown collocations from academic lectures, whereas the present study particularly involved young students learning via a non-academic narrative plot. As the present qualitative findings revealed, learning in such a story context and relatively simple linguistic features may enhance young learners’ engagement (Lenhart et al. 2020) and reduce their cognitive load (Montero Perez 2020), especially with the aid of either auditory or visual input.

For meaning recall knowledge, students in the VWC group significantly outperformed those in the other two groups, while no significant differences were observed between the RO and RWL groups. This supports Pu et al.’s (Pu et al. 2024) research but demonstrates a mixed perspective towards Vu et al's. (2023) research. Although Vu et al. (2023) highlighted the positive effect of captioned TV viewing on the learning of productive collocation knowledge, they did, however, claim that reading-while-listening was equally effective as viewing captioned videos for collocation acquisition at the recall level. The reasons for this conflict in findings may stem from the different learner cohorts involved in multimodal conditions. The present qualitative results further explain that when dealing with a more sensitive collocation knowledge test (Nation 2013; Read 2019), young learners appear to benefit from the connections among dynamic images, pronunciation, and written forms of unknown collocations to facilitate meaning comprehension.

Although learners from the RWL and VWC groups initially gained better vocabulary knowledge, all three learning groups showed no significant differences in their delayed post-test scores for form recognition and meaning recall. One possible explanation is that insufficient exposure and access to the target collocations may diminish the immediate learning effects of multimodal incidental learning, in turn leading to no differences in the delayed post-test scores among the three groups.

While the immediate collocation performance in the two multimodal groups yielded no statistical difference, the present qualitative findings recommend the positive learning experiences associated with engaging in multimodal input. Specifically, learners in the RWL and VWC groups expressed favorable attitudes towards multimodal conditions. Such endorsement not only generally supports how learners are facilitated by multimodal input in various settings, such as speaking (Pu and Chang 2023) and writing (Chen 2021), but also contributes a new set of empirical findings to the literature on incidental collocation learning. That is, exposing students to multiple sources of input at the same time is very likely to facilitate them effectively by utilizing the information from each mode and integrating clues from various channels (Mayers 2020), thereby activating information processing systems and finally enhancing learning outcomes and experiences. However, readers should interpret our highly positive qualitative findings with caution when considering their applicability to other educational contexts. This caution is warranted primarily due to the sample selection and the voluntary nature of our interviews, which may have induced self-selection biases. Possibly, more engaged or satisfied students were more inclined to participate, potentially producing responses that aligned with perceived expectations rather than offering fully candid reflections.

6.2 Changes in Collocation Gains Over Time Within Each Input Mode

After two weeks, the three groups all showed a decline in their collocation gains at both the recognition and recall levels. Nevertheless, young EFL learners were able to retain a higher relative learning rate at the receptive collocation level compared to productive knowledge. This is not a surprising finding because it aligns with several earlier studies on incidental single-word gains after four-week decay (e.g., Waring and Takaki 2003; Brown et al. 2008) and with a latest one on incidental collocation gains after two-week decay (Pu et al. 2024). These studies jointly claimed that both adult and young learners’ knowledge of single word-items and collocations gained from incidental learning significantly decreased within two to four weeks, but receptive knowledge lasted longer than productive knowledge.

In terms of meaning recall, only the VWC group exhibited a significant decay, but the reader should be cautious when interpreting the results for the RO and RWL groups. First, the RO group could not recall any target collocation's meaning after a 2-week interval, resulting in no statistical differences between the two timings of this group. Second, the RWL group yielded exactly the same low relative learning rate (1.29%) in both post and delayed post-tests, resulting in a mean difference of zero. Although the RWL group showed no significant decay, it is possible to claim that the learning effects observed in this group were not due to retained learning effects but rather could have occurred by chance.

Taken together, the study suggests the immediate effectiveness of RWL and VWC in incidental collocation learning. However, this effectiveness appears to decay over time, though with the VWC group still outperforming the other two groups, albeit without statistical significance. Such observed decay is not surprising but is actually predictable for two reasons. First, receptive (i.e., form recognition) collocation knowledge is generally easier to acquire than productive (i.e., meaning recall) knowledge across various learning modes, such as reading-only (Pellicer-Sánchez 2017), reading-while-listening (Webb and Chang 2022), and viewing with captions (Teng 2019). Second, due to the study's focus, variables during the interval between the post-test and delayed post-test were not controlled, potentially limiting participants’ exposure to the target collocations. This might then emphasize the importance of providing additional exposure and access to target collocations to maintain long-term learning effects, particularly among young EFL learners. Further research that specifically investigates extended exposure post-immediate learning is thus warranted.

7 Implications

Multimodal input, specifically reading-while-listening and viewing with captions, facilitated young EFL learners’ collocation learning at both recognition and recall levels, with viewing-with-captions contributing more significantly to productive knowledge. From a theoretical perspective, this finding provides insights into the applicability of Mayer's modality and redundancy principles for young EFL learners. While the modality principle was further affirmed, the redundancy principle did not apply to young EFL learners’ L2 collocation learning in this study. From a pedagogical perspective, these findings suggest that L2 teachers and practitioners should consider integrating both types of multimodal input for young learners. For one thing, the presentation modes of reading materials should be tailored to the specific aspects of collocation knowledge being targeted. For another, when storytelling materials are used as meaning-focused input for young English learners, videos with captions may enhance learning more effectively than the other input modes examined. Moreover, given the potential decay effect of incidental learning, integrating newly, incidentally acquired collocations through explicit reinforcement would help consolidate learning. Finally, from a methodological perspective, this study employed a mixed-methods design to explore young EFL learners’ perceptions of different collocation learning conditions, offering an in-depth understanding of their voice with the two types of multimodal input in relation to the modality and redundancy principles.

8 Conclusion

The present study contributes to the literature by comparing how multimodal (i.e., reading-while-listening and viewing with captions) input facilitates young EFL learners’ incidental collocation acquisition, compared to reading-only input and by exploring their learning experience and perceptions of different input modes. Overall, both types of multimodal conditions contributed positively to incidental collocation learning at both recognition and recall levels and were favored by the learners. The multimodal condition is found to facilitate learners in acquiring productive knowledge more effectively, immediately after learning with the corresponding input mode. Despite the decay after two weeks, learners in the multimodal condition still demonstrated better performance in terms of receptive knowledge. These findings provide further support for the effectiveness of multimodal input in incidental collocation learning and insights into selecting appropriate modes to present reading materials for young learners.

Nevertheless, three main limitations should be acknowledged. First, the present study did not conduct a longitudinal treatment on younger participants, which may result in limited collocation knowledge gains, particularly in productive knowledge. Second, the findings of the present study are based on purposive sampling. Caution should be exercised when readers attempt to generalize the results to the wider population of young EFL learners globally. Future research on the effect of multimodal learning conditions on L2 young learners could implement treatments over an academic term and incorporate a wide range of samples and diverse collocation formats. Moreover, the overwhelmingly positive feedback from interviewees in the two multimodal groups highlights the need for future research to adopt anonymous questionnaires with opened ended questions to explore fuller understandings of young learners’ learning experiences and perceptions. Third, although all three groups received the same total treatment time, whether every participant was fully engaged with the material is another aspect worth further investigation. Last, the present study was limited to one genre of young learners’ materials (i.e., storytelling). Future studies could explore various genres of young learners’ literature, such as science/historical fiction, non-fiction, and biography.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the University of Bristol PhD Scholarship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.