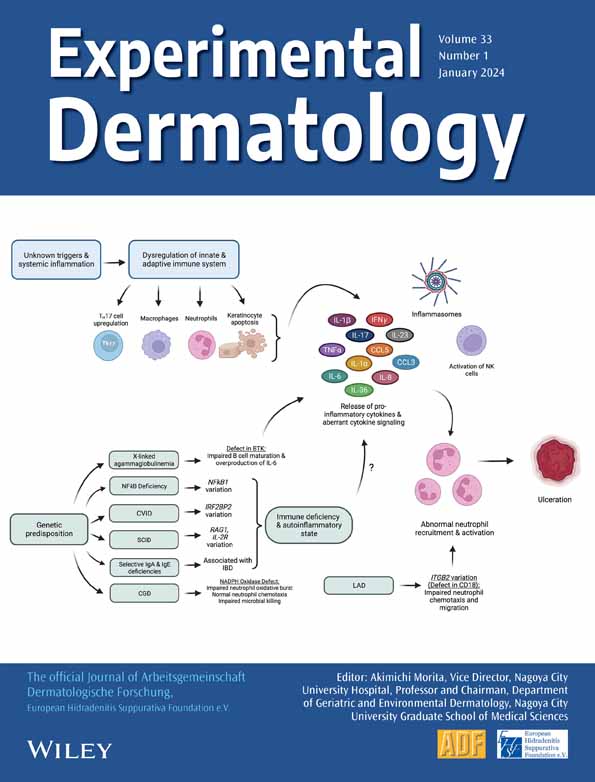

Local neutrophil and eosinophil extracellular traps formation in pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans

Abstract

Pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans is a rare inflammatory condition, affecting the skin and/or mucous membrane. Some cases include both skin and mucous involvement, whereas others develop either skin or mucous lesions only. The typically affected areas are the scalp, face, trunk and extremities, including the flexural areas and umbilicus. Clinical features show erosive granulomatous plaques, keratotic plaques with overlying crusts and pustular lesions. Among mucous lesions, oral mucosa is most frequently involved, and gingival erythema, shallow erosions, cobblestone-like papules on the buccal mucosa or upper hard palate of the oral cavity are also observed. Some of the lesions assume a ‘snail track’ appearance. Although there are several similarities between pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans and other diseases, that is pyoderma gangrenosum, pemphigus vegetans and pemphigoid vegetans, the histopathological features of pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans are unique in that epidermal hyperplasia, focal acantholysis and dense inflammatory infiltrates with intraepidermal and subepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses are observed. Direct immunofluorescence findings are principally negative. Activated neutrophils are supposed to play an important role in the pathogenesis of pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans. The expression of IL-36 and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) was observed in the lesional skin, and additionally, eosinophil extracellular traps (EETs) was detected in pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans. A possible pathogenic role of NETs and EETs in the innate immunity and autoinflammatory aspects of pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans was discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans is a rare inflammatory mucocutaneous condition, involving the scalp, face, axilla, umbilicus and oral cavity.1-3 Histopathologically, epidermal hyperplasia, focal acantholysis and dense inflammatory infiltrates with intraepidermal and subepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses can occur. There are several similarities between pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans and other autoinflammatory neutrophilic or autoimmune bullous diseases; therefore, the diagnosis is sometimes difficult. Herein, we report local expression of NETs and IL-36 in the pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans lesions and discuss insights into the role of neutrophils in the pathogenesis of this rare disease.

2 CLINICAL FEATURES

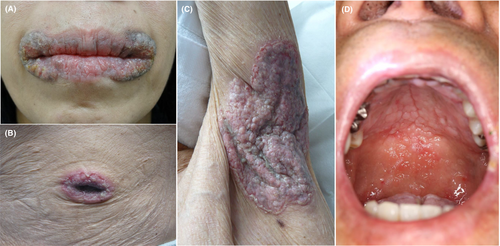

Pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans is a rare variant of neutrophilic disorders that involves the intertriginous areas such as the axilla and groin, as well as the umbilicus, trunk and extremities. In addition, oral mucosa is involved. Occasionally, only the skin (pyodermatitis vegetans) or mucosa (pyostomatitis vegetans) is involved. The clinical features are erosive granulomatous plaques, keratotic plaques with overlying scales and pustules (Figure 1A–C); thus, pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans is closely related to pyoderma gangrenosum.

Oral involvement presents with erythematous, erosive, thickened and hyperplastic folds of the buccal and labial mucosa with a number of yellow pustules and crusts on the hard and soft plate of the buccal mucosa (Figure 1D). They form shallow, folded and fissured ulcers, termed as snail track (tract). Other than the oral cavity, mucosal membranes at the vaginal, nasal and periocular areas can be affected. Anogenital areas are occasionally affected and refractory erosive erythema are observed. By contrast, ocular involvement is rarely reported.4-6

Peripheral blood eosinophilia was observed in patients with pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans. In our four patients, the eosinophil to neutrophil ratio was between 1:2.5 and 1:5.

3 HISTOPATHOLOGICAL FEATURES

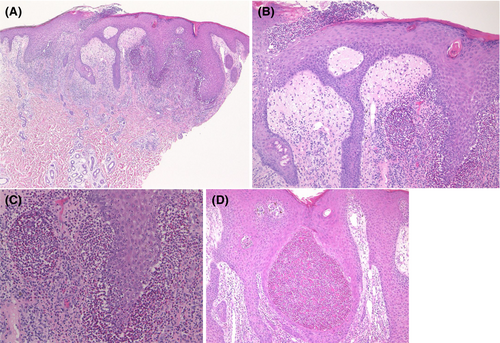

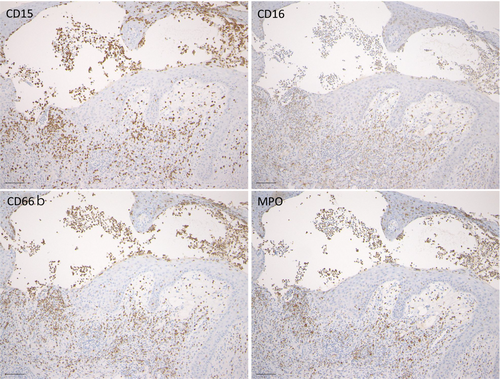

Pyodermatitis vegetans is histopathologically characterised by irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with superficial subcorneal neutrophilic abscesses, infiltration of eosinophils, neutrophils and mononuclear cells, and dilated vessels in the subepidermal oedema (Figure 2A–C). Occasionally, eosinophilic abscesses can be seen in the epidermis (Figure 2D). Both neutrophilic and eosinophilic abscesses can be observed within the epidermis. Expression of CD15, CD16, CD66a and myeloperoxidase (MPO) was also detected in the neutrophilic abscess in the epidermis (Figure 3A–D).

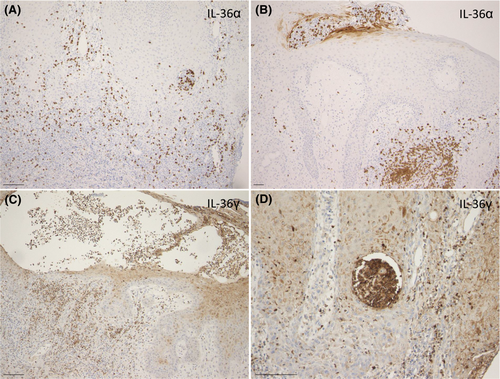

4 LOCAL EXPRESSION OF IL-36 AND NETs

Biopsy samples were obtained from four patients with pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans. Using the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections, IL-36 expression was examined. IL-36 is an IL-1 family cytokine, and both IL-1 and IL-36 play an important role in the pathogenesis of several inflammatory diseases. IL-36 can be secreted by keratinocytes, macrophages/monocytes, T cells, neutrophils, dendritic cells and plasma cells. IL-36 binds to IL-36R and prompts inflammatory responses by activating and regulating several inflammatory pathways including nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and activator protein-1 (AP-1). In the lesional skin of pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans, IL-36α expression was observed in the neutrophilic abscesses in the epidermis as well as neutrophilic infiltration in the dermis (Figure 4A,B), while IL-36γ was detected in the keratinocytes and infiltrating inflammatory cells including neutrophils and mononuclear cells within and below the epidermis (Figure 4C,D). The localization of IL-36 suggests the active innate immunity in the pathogenesis of pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans.

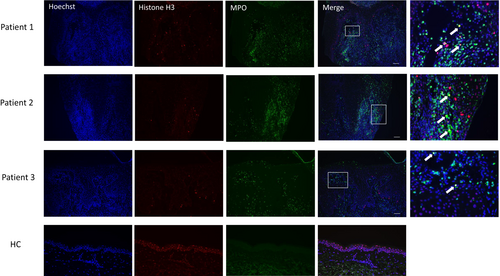

Neutrophils play an important role in the initiation, promotion and perpetuation of immune dysregulation via proinflammatory cytokine production, tissue damage through reactive oxygen species and formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs).7 NETs are composed of extracellular structures such as DNA, histones and neutrophil granules containing neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase.8 Recent studies have shown increased NETs expression in the skin tissues of pyoderma gangrenosum.9, 10

To detect local expression of NETs, DNA was immunofluorescently stained with Hoechst 33342, MPO and citrullinated histone H3 (citH3). Merged photos showed a number of NETotic neutrophils in the epidermis and dermis (Figure 5). The lesional skin of pyodermatitis vegetans was characterised by the presence of NETs, which were not observed in normal skins. These results suggest that NETing neutrophils play a significant role in the development of pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans.

NETs promote inflammation, and skin injury; thus, excessive levels of NETs can damage the epidermis.11 The tissue-damaging capacity of NETs may explain the erosive, granulomatous appearance of pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans. NETs regulate inflammatory cytokines in response to alarmins. NETs stimulate macrophages to secret IL-1β, recruit neutrophils, thereby further promoting their own progression.12 Moreover, NETs can stimulate airway epithelial cells to secret IL-1 family cytokines, such as IL-36. Neutrophil elastase cleaves IL-36 receptor antagonist into its highly active form.13 In addition, neutrophil-derived proteases escalate inflammation by IL-36-α, −β, and -γ maturation and activation.14 The positive feedback loop between neutrophils and NETs promotes further formation of NETs, which act on keratinocytes. NETs may play a pathogenic role in pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans by amplifying inflammation and tissue damages.

5 LOCAL EXPRESSION OF EOSINOPHIL EXTRACELLULAR TRAPS (EETs)

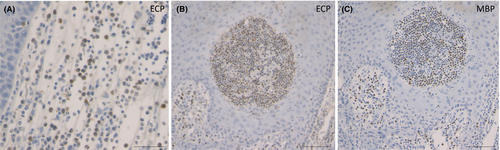

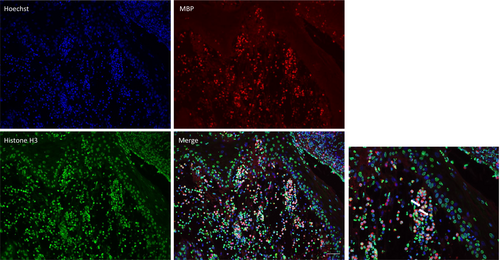

As described above, not only neutrophils but also eosinophils are abundantly observed within and below the epidermis. A number of eosinophils are positive for eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) (Figure 6A,B), and major basic protein (MBP) (Figure 6C). In addition to neutrophils, a number of eosinophil infiltrations occurred in the epidermis as well as below the epidermis. Thus, eosinophils may also play a role by releasing granules. Recently, eosinophil extracellular traps cell death (ETosis) has been recognised in tissues of eosinophilic diseases.15, 16 To examine the formation of eosinophil extracellular traps (EETs), DNA was immunofluorescently stained with Hoechst 33342, MBP and citrullinated histone H3 (citH3). Merged photos showed ETotic eosinophils in the epidermis and dermis (Figure 7).

Eosinophils secret various cytokines, chemokines and growth factors upon activation. Among them, alarmins such as IL-33, belonging to IL-1 family cytokine, are released by eosinophils and play a role in the innate immunity, allergy, inflammation and tissue remodelling; however, the role of eosinophils in the pathogenesis of pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans is unknown.

6 COMORBIDITIES

Pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans is associated with inflammatory bowel disease, in particular ulcerative colitis (UC). The frequency of extra-intestinal manifestations has been reported to be up to around 40%,17 in which mucocutaneous manifestations are one of the most common symptoms. The prevalence of cutaneous manifestations is roughly equal for Crohn's disease (CD) (9%–19%) and UC (9%–23%).18 The representative cutaneous manifestation of UC are pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum, as well as other disorders such as hidradenitis suppurativa, psoriasis, lichen planus and atopic dermatitis. Additionally, there are many cases of pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans reported in patients with active, inactive or asymptomatic UC.19-21 Recent studies have suggested that IL-36 plays an important role in intestinal immunity,22 indicating a shared pathogenesis involving IL-36 between pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans and UC.

7 PAEDIATRIC CASES

Paediatric cases are less frequent, most of which are associated with inflammatory bowel diseases23; however, the frequency has not yet been accurately evaluated. In paediatric cases of pyoderma gangrenosum, various underlying diseases, such as hematopathy, juvenile inflammatory arthritis, Takayasu's arteritis and autoinflammatory diseases, have been reported. Further accumulation of paediatric cases is necessary to examine the possible relationship between pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans and systemic diseases.

8 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Pyoderma gangrenosum is clinically classified into 5 types, that is ulcerative, bullous, pustular, vegetative and peri-stomal types. Pustular pyoderma gangrenosum is a rare type, and pustules can be seen on the back or scalp. Vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum is a superficial, non-aggressive form with a verrucous appearance, that is nowadays considered to be the same as superficial granulomatous pyoderma. Association with UC is the most frequently observed in pyoderma gangrenosum. Therefore, pyoderma gangrenosum and pyodermatitis vegetans have several similarities, and some consider that pyodermatitis vegetans may be a granulomatous or vegetative variant of pyoderma gangrenosum. By contrast, the involvement of oral or genital regions is rare in pyoderma gangrenosum.

Amicrobial pustulosis (APF) is a rare condition and is included as one of the neutrophilic dermatoses. It mainly affects the scalp and ear canals, as well as intertriginous areas such as the axillary, groin and perianal regions. APF is characterised by sterile small pustules and erythemas, and histopathologically, subcorneal or intraepidermal neutrophil infiltration sometimes forms spongiform pustules, parakeratosis and cellular infiltrates in the upper dermis. Pustules are both follicular and non-follicular. APF is known to occur in patients with autoimmune diseases such as SLE. In addition, APF has recently been suggested to be included in autoinflammatory disorders, and several cases of APF in association with neutrophilic dermatosis such as palmoplantar pustulosis and pyoderma gangrenosum have been reported.24, 25

Pemphigus, especially pemphigus vegetans and IgA pemphigus, is also an important disease with shared pathogenesis with pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans, because immunofluorescence examination can detect IgA or C3 deposition1, 3 or serum antibodies against BP180 or BP230 can be sometimes detected.26-28 There are two types of pemphigus vegetans; Neumann type and Hallopeau type. The former begins as vesicles while the latter begins as pustules. Histopathologic features between pemphigus vegetans and pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans are similar; thus, immunofluorescence analysis is important to differentiate between the two disorders29; however, differentiation of pemphigus vegetans, IgA pemphigus, and pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans is sometimes difficult.30

Pemphigoid vegetans is a very rare type of bullous pemphigoid but findings of linear IgG or C3 deposition along with the basement membrane of the epidermis by direct immunofluorescence are the diagnostic clue.31

9 TREATMENT

Oral glucocorticosteroid, dapsone, cyclosporine, azathioprine, minocycline, mycophenolate mofetil and isotretinoin have been used, but some of the cases are refractory. In particular, oral dapsone is favourably used with sufficient effects.32 In cases of coexisting active inflammatory bowel diseases, biologics can be used to control the skin conditions. Topical corticosteroid ointment is also used in combination with systemic therapies.

10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Further studies are necessary into whether the low-density granulocytes are increased in the peripheral blood of the patients with pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans. In addition to neutrophils, a number of eosinophil infiltrations occurred in the epidermis as well as below the epidermis. Thus, eosinophils may also play a role by releasing granules. This study showed that not only neutrophils but also eosinophils generate ETs in the lesional skin of pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans. The generation of reactive oxygen species and the involvement of enzymes may be common. Therefore, new insights into the role of EETosis in pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans may be helpful for the understanding of the pathogenesis. Although there is a possibility that EETosis is not a disease-specific phenomenon, prominent eosinophil infiltration forming eosinophilic abscess may be a characteristic feature of pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans, which may be helpful for differentiation from pyoderma gangrenosum. Further studies are necessary to determine the significant role of EETs and released cytokines released from activated eosinophils in the pathogenesis of pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans. Moreover, oral and gut microbiota may be impaired in patients with pyodermatitis pyostomatitis vegetans and should be further investigated.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

TY designed the study, and performed the data collection, research and contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. TY wrote the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Tomoko Okada for technical support.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Author elects to not share data.