“Code Headache”: Development of a protocol for optimizing headache management in the emergency room

Abstract

Background and Purpose

Patients presenting at the emergency room (ER) with headache often encounter a hostile atmosphere and experience delays in diagnosis and treatment. The aim of this study was to design a protocol for the ER with the goal of optimizing the care of patients with urgent headache to facilitate diagnosis and expedite treatment.

Methods

A narrative literature review was conducted via a MEDLINE search in October 2021. The “Code Headache” protocol was then developed considering the available characteristics and resources of the ER at a tertiary care center within the Spanish National Public Health system.

Results

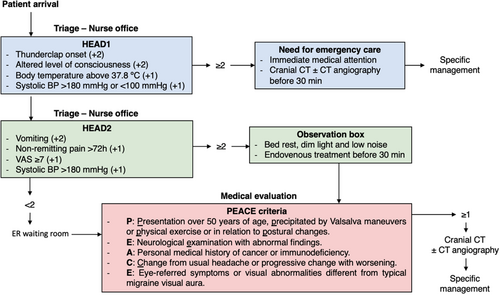

The Code Headache protocol comprises three assessments: two scales and one checklist. The assessments identify known red flags and stratify patients based on suspected primary/secondary headaches and the need for pain treatment. Initial assessments, performed by the triage nurse, aim to first exclude potentially high morbidity and mortality etiologies (HEAD1 scale) and then expedite appropriate pain management (HEAD2 scale) based on scoring criteria. HEAD1 evaluates vital signs and symptoms of secondary serious headache disorders that can most benefit from earlier identification and treatment, while HEAD2 assesses symptoms indicative of status migrainosus, pain intensity, and vital signs. Subsequently, ER physicians employ a third assessment that reviews red flags for secondary headaches (grouped under the acronym ‘PEACE’) to guide the selection of complementary tests and aid diagnosis.

Conclusions

The Code Headache protocol is a much needed tool to facilitate quick clinical assessment and improve patient care in the ER. Further validation through comparison with standard clinical practice is warranted.

INTRODUCTION

Headache is the main reason for patient consultation in tertiary hospital emergency room (ER) settings, accounting for 1%–3% of all visits [1-4]. Data from a multinational registry showed that 59.5% of headache patients presenting to the ER are diagnosed with primary headache, migraine in most cases, while 40.5% have secondary headaches, which may cause high morbidity and mortality in 7.1% of patients [5]. This becomes a problem when there is under-triage of headache patients in ERs, with a reported 85.1% of patients who should be classified as “emergency” level and 23.3% as “urgent” level being misclassified [6]. Incorrect classification of these patients results in diagnostic and therapeutic delay, with increased length of stay in the ER, increased likelihood of new consultation after discharge, and increased resource consumption, both in patients with primary and patients with secondary headaches. Headache patients who are under-triaged as non-urgent can wait up to 4 hours [7]. After a correctly targeted anamnesis and clinical and neurological examination by ER physicians, most urgent headache cases can be identified by reviewing the red flags of secondary etiology. Red flags of secondary headache have been well researched and described [8] but they were not conceived to include other urgent cases, such as primary headaches with a severe attack that require prompt treatment in the ER. Furthermore, there is a lack of specific tools for risk classification and triage of headache patients arriving at the ER.

The objective of this study, therefore, was to develop a protocol that could help establish a “Code Headache” (mimicking the vocabulary used, for example, in “Code Stroke”), with diagnostic and therapeutic intention. We intended that the protocol should: (1) include the known “secondary headache red flags”, to exclude potential severe morbi-mortality etiologies; (2) be based on a quick scoring system, in order to facilitate and expedite care in the ER; (3) be easily implemented by non-headache experts and non-neurologists; and (4) improve access to pain treatment in both primary and secondary headache cases, avoiding unnecessary delays and prioritizing pain care.

METHODS

Setting

- MAT 1–2: The need for emergency care (unstable patients or those potentially requiring immediate attention by the medical team, estimated wait time between 15 and 20 min);

- MAT 3–4: Transfer to the observation box and waiting in bed until medical attention (estimated wait time until attention 20 to 30 min);

- MAT 5: Placement in the waiting room for assessment in the medical office (estimated wait time 2 to 4 h).

Literature review

To research the most useful and up-to-date resources in urgent headache management in the ER (both primary headache treatment and secondary headache identification), a narrative literature review was conducted in October 2021 via MEDLINE. The following terms were used: “headache”, “emergency department”, “red flags”, “treatment”, “guideline”, and “length-of-stay”, and studies published from 2010 to 2021 were considered. Articles published prior to 2010 were not included to avoid guidelines that may be outdated and studies that could not use contemporary diagnostic methods. Local guidelines were prioritized, as other guidelines could not take into account the resources available in our setting.

Ethics

Approval for this study was obtained from the Vall d'Hebron Ethics Committee PR(AG)396/2022. All participants gave their consent for data collection.

RESULTS

- The disorders with most morbi-mortality that present with headache as the main symptom in the ER are intracranial hemorrhage (in particular, subarachnoid hemorrhage [SAH]) and central nervous system (CNS) infection (specifically, infectious meningitis) [5]. These two disorders benefit from prompt identification as treatment can be implemented and the prognosis is time-dependent (aneurysm intervention in aneurysmatic SAH and antiviral or antibiotics in CNS infection) [10, 11].

- Some clinical red flags are more associated with secondary headache causes than others. Specifically, thunderclap headache and altered level of consciousness carry more risk in SAH and CNS infection (especially when high blood pressure (BP) or fever, respectively, are present) [5].

- Other severe headache cases, such as brain venous thrombosis and spontaneous intracranial hypotension, that also present with headache as the main symptom, are associated with high morbidity and the prognosis is better the earlier the case is identified, but they are uncommon and the clinical syndrome can be too complex for identification in the triage office [5].

- Ischemic stroke and epileptic seizures can also be associated with headache but other neurological symptoms are usually prominent and they are better managed by other protocols [12].

- Cranial CT is indicated in most patients with red flags for secondary headache in the ER [5]. Medication overuse and drug-induced headache are notable exceptions [8]. A protocol including the indication of cranial CT should not include this specific situation as a red flag.

- The most complete and up-to-date tool for red flags for secondary headache identification were described by the Secondary Headache Special Interest Group of the International Headache Society, who used the acronym SNNOOP10 [8]. However, these red flags are not structured in the form of a score or an algorithm for quick use in triage. The items included in SNNOOP10 are: (1) systemic symptoms including fever (not considered as a red flag if isolated fever); (2) history of neoplasm; (3) focal neurological deficit; (4) thunderclap onset; (5) onset after 50 years; (6) pattern change or recent onset; (7) positional/orthostatic headache; (8) symptoms precipitated by the Valsalva maneuver; (9) papilledema; (10) progressive evolution; (11) pregnancy or puerperium; (12) painful eye with autonomic features; (13) posttraumatic onset; (14) immunosuppression; and (15) painkiller overuse or new drug use at onset of headache.

- Some headache cases should be excluded from the Headache Code as they benefit from specific care and protocols and can be identified in triage. Such cases include pregnant women, pediatric patients, headache after cranial trauma, need for management in the COVID-19 circuit, association of headache with focal neurological deficits (management as with Code Stroke) and consultation for a headache episode that has already resolved (asymptomatic patients).

- The most specific and useful guideline in our setting for symptomatic treatment of primary and secondary headache in the ER is the Spanish Neurology Society Headache in the ER guideline [13]. Other guidelines for ER management of headache that were taken into account were the from the American College of Emergency Physicians [14] and the French Society of Neurology [15].

- Primary headache cases seen in the ER are mainly represented by migraine (cluster headache, tension type headache and other primary headache are rare) [5]. Bed rest and endovenous drugs (especially when vomiting is present) are recommended treatments in status migrainosus [13, 15].

- Protocol-guided nurse prescription of analgesia in specific scenarios is considered safe, and decreases wait-to-treatment and patient length of stay in the ER in a pain-related condition [16-19].

The Headache Code was developed as a protocol in which three scales are consecutively used with different objectives: HEAD1 aims to identify cases of headache secondary to diseases with higher morbi-mortality as soon as the patient arrives at the hospital, HEAD2 helps to prioritize the need for early intravenous treatment, and ‘PEACE’ is a review of the remaining red flags of secondary headaches. A graphical representation of Code Headache can be found in Figure 1.

HEAD1 includes items based on priority red flags for headache attributed to SAH and CNS infections: thunderclap onset (+2 points), altered level of consciousness (+2 points), body temperature above 37.8°C (+1 point) and systolic BP above 180 mmHg or below 100 mmHg (+1 point). Cases with a HEAD1 score of 2 points or more will be triaged as needing emergency care and assessed by the medical team immediately for case orientation (MAT 1–2), for cranial CT as soon as possible (before 30 min), followed by specific management.

To decide the triage of cases scoring fewer than 2 points on the HEAD1, the same nurse will then use the HEAD2 score. This second tool aims to identify cases of status migrainosus and other primary or secondary headaches that may benefit from earlier symptomatic treatment. The items included in HEAD2 are: vomiting (+2 points), non-remitting pain for more than 72 h (+1 point), pain intensity of at least 7 out of 10 on the visual analogue scale (+1 point), refractoriness to self-administered analgesic medication prior to ER consultation (+1 point) and systolic BP above 180 mmHg (+1 point). Patients with a HEAD2 score of 2 points or more will be placed in bed in an observation box (MAT 3-4), a dimly lit environment with low noise level. Per protocol, these cases have a target waiting time to treatment of less than 30 min. In cases of HEAD2 with a score of less than 2, patients will enter the MAT 5 evaluation.

- (P) Presentation over 50 years of age, precipitated by Valsalva maneuvers or physical exercise or in relation to postural changes.

- (E) Neurological examination with abnormal findings.

- (A) Medical history of cancer or immunodeficiency.

- (C) Change from usual headache or progressive change with worsening.

- (E) Eye-referred symptoms or visual abnormalities different from typical migraine visual aura.

If any red flags are identified in the PEACE assessment of the patient, a cranial CT will be indicated and managed accordingly.

DISCUSSION

Code Headache has been developed as a protocol in which three consecutive scales can be used to classify the risk of severe secondary headache cases, guide triage, improve waiting times for analgesia and aid in secondary red flag identification.

One of the main objectives of the protocol is the early identification of secondary headaches with a severe cause to avoid diagnosis and care delays. SNNOOP10 is the most up-to-date version of a list with proposed clinical data for patients with secondary headache suspicion [8]. The usefulness of SNNOOP10 has recently been validated in the ER setting, with 100% sensitivity of the SNNOOP10 protocol for detecting high-risk secondary headaches [20]. In our protocol, all the SNNOOP10 items are included in the HEAD1 score and the PEACE criteria, except for head injury, headache in pregnant women and headache associated with excessive use of analgesics or related to a drug. As previously stated, it was decided that patients who presented with headache during pregnancy or after head injury would be excluded from this protocol, as they would benefit from specific management, although in the future a special protocol for such patients should be developed. An item referring to medication overuse or drug-induced headache was not included in the PEACE criteria, since one of the aims of PEACE is to guide the decision to request a cranial CT and usually this patient profile does not benefit from this complementary test if there are no other associated red flags. HEAD1 and PEACE have benefits versus SNNOOP10 as they are integrated into the Code Headache protocol, with the evaluation of the most relevant red flags started as soon as the patient arrives at the ER (in the triage assessment) and using a scoring system that helps triage nurses make decisions. Other investigations have described green flags that aid primary headache diagnosis [21]; these have been used for proposed algorithms to help headache diagnosis [22], but are not specific to headache in the ER. Furthermore, the Code Headache protocol as a whole goes beyond the identification of red flags of secondary headache, incorporating the HEAD2 score, an assessment to select cases which may benefit from earlier treatment that should be administered as soon as possible. The Code Headache protocol could reduce the time to diagnosis of secondary headaches of serious cause as the review of red flags starts at triage. With the usual triage systems in the ER of our hospital, any headache patient without symptoms suggestive of focal neurological deficits identified at triage is placed in the waiting room for assessment by physicians (MAT 5, with an estimated wait time of 2 to 4 h), with the need for further waiting time until medication administration by the nurse. The protocol could reduce time to treatment for patients with HEAD2 score ≥2 through prescription by nurses, as they are the first professionals to receive the patients in the observation boxes. As mentioned earlier, treatment prescription by ER nurses for certain conditions under specific protocols and based on easy-to-use scores could improve patient outcomes and is proven to be safe in pain-related conditions [16, 17, 19]. The administration of analgesia for pain disorders is one of the most recognized clinical scenarios in which treatment prescription by nurses, before final medical diagnosis, is deemed appropriate [18] and this practice has been included in Spanish law (Royal Decree 954/2015 regulating the indication, use and authorization of dispensing of medicines and medical devices for human use by nurses) [23].

With the aim of identifying the most severe conditions, the HEAD1 items were designed taking into account the results of the HEAD study, a multicenter, multinational observational study with epidemiological and clinical data on more than 4500 patients who presented to the ER for headache [5]. This study described the frequency of serious secondary causes when certain clinical features are reported by headache patients. The objective of HEAD1 is to identify headache cases suggestive of SAH or CNS infection. Major symptoms of SAH are thunderclap headache, focal neurological deficits and seizures; however, headache is regarded as the most common symptom, it can be the only symptom at SAH onset, and SAH should be considered in all patients with sudden-onset severe headache [24]. The identification of thunderclap headache can be made quickly in triage by nurse staff. As previously mentioned, thunderclap headache was the symptom most associated with a secondary severe headache etiology in the HEAD study. After thunderclap headache, altered level of consciousness was the next symptom most associated with a serious secondary headache cause in the ER, and can appear both in CNS infection and SAH. Patients with an altered level of consciousness may have difficulty describing the semiology of their headache, therefore, a thunderclap onset may go unnoticed in such patients and SAH identification may be delayed [25]. For these reasons, thunderclap onset and altered level of consciousness were designed to add 2 points in HEAD1. Fever was also included in HEAD1, but 1 point instead of 2 is added as fever is not considered a red flag in SNNOOP10 when it presents by itself. Lastly, high BP was also included with a weight of 1 as this is a common sign in SAH, and low BP was also included because, if presenting in combination with fever (adding +2 points combining both items and qualifying for need for emergency care by protocol), this could help to identify CNS cases that present with headache, fever and low BP as a sign of sepsis [26].

For HEAD2 development, items related to the diagnostic criteria of status migrainosus were taken into account. This disorder is defined in the third edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders as a headache attack in a migraine patient that is ongoing for more than 72 h and in which the pain or associated symptoms are debilitating [27]. Vomiting was selected as an item with greater weight on the scale (+2 points if present) [28], as this is a feature of severity both in migraine (where it has been described as one of the most bothersome symptoms) [28] and other conditions and indicates that the patient is a candidate for early intravenous treatment as they cannot tolerate oral treatment. However, it must be taken into account that this score is designed for triage and does not replace a clinical evaluation: headaches other than migraine can also score 2 points or more in HEAD2. Other possible items for a score as HEAD2 could be “prior migraine attacks” or “patient identifies the situation as migraine”, but these were not included in order to maintain simplicity in the nurse evaluation and avoid the over-diagnosis of migraine, as migraine patients experiencing headaches of other etiologies can be misdiagnosed.

The Code Headache protocol is not without limitations. Firstly, it is not applicable for certain populations by design (pregnant women, pediatric patients, headache after cranial trauma, stroke and already resolved headache). The application of this innovative protocol requires important work on education, awareness, training and communication between neurology and emergency teams, including nurses. Another limitation is that there are currently no data on the specificity and sensitivity of the Headache Code for identification of serious headache secondary etiologies and/or its capacity to adequately improve treatment and waiting time in the ER. Its validation requires comparison of its results with standard clinical practice.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, Code Headache is an algorithm-type protocol designed to improve the care of patients with headache and to minimize delays in the ER by providing tools for early diagnosis and treatment. The protocol should be validated by comparing it with standard clinical practice.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Javier A. Membrilla: Conceptualization; investigation; writing – original draft; methodology; writing – review and editing; formal analysis; data curation. Alicia Alpuente: Conceptualization; investigation; writing – review and editing; supervision; project administration. Laura Gómez-Dabo: Supervision; formal analysis. García-Yu Raúl: Methodology; validation; formal analysis; data curation. Eduardo Mariño: Data curation; methodology; validation; formal analysis. Javier Díaz-de-Terán: Supervision; writing – review and editing. Patricia Pozo-Rosich: Conceptualization; investigation; funding acquisition; writing – review and editing; visualization; validation; methodology; formal analysis; project administration; data curation; supervision; resources.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Membrilla JA has received honoraria for teaching activities from TEVA, Lilly and Novartis and for advisory from Pfizer. Alpuente A has received honoraria as a speaker from Lundbeck, Allergan-Abbvie, Novartis, Lilly, TEVA and as a consultant from Medlink. Gomez Dabo L does not have any conflicts of interest. García-Yu R and Mariño E report no conflict of interest. Diaz-de-Terán J has received honoraria for advisory boards from speaker panels from Novartis, Lilly, TEVA, Abbvie-Allergan, Lundbeck Pfizer and Boston Scientific. In the last three years, Pozo-Rosich P has received honoraria as a consultant and speaker for: Abbvie, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Medscape, Novartis, Pfizer and Teva. Her research group has received research grants from AbbVie, Novartis and Teva, as well as Instituto Salud Carlos III, EraNet Neuron and European Regional Development Fund (001-P-001682) under the framework of the FEDER Operative Programme for Catalunya 2014-2020–RIS3CAT; has received funding for clinical trials from AbbVie, Amgen, Biohaven, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis, Pfizer and Teva. She is the Honorary Secretary of the International Headache Society. She is in the editorial board of Neurologia, and Revista de Neurologia, associate editor for Cephalalgia, Headache and The Journal of Headache and Pain. She is a member of the Clinical Trials Guidelines Committee and Scientific Committee of the International Headache Society. She has edited the Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Headache of the Spanish Neurological Society. She is the founder of www.midolordecabeza.org. Pozo-Rosich P does not own stocks from any pharmaceutical company.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.