What impacts the acceptability of wearable devices that detect opioid overdose in people who use opioids? A qualitative study

Basak Tas and Hollie Walker are joint first authors.

Abstract

Introduction

Drug-related deaths involving an opioid are at all-time highs across the United Kingdom. Current overdose antidotes (naloxone) require events to be witnessed and recognised for reversal. Wearable technologies have potential for remote overdose detection or response but their acceptability among people who use opioids (PWUO) is not well understood. This study explored facilitators and barriers to wearable technology acceptability to PWUO.

Methods

Twenty-four participants (79% male, average age 46 years) with current (n = 15) and past (n = 9) illicit heroin use and 54% (n = 13) who were engaged in opioid substitution therapy participated in semi-structured interviews (n = 7) and three focus groups (n = 17) in London and Nottingham from March to June 2022. Participants evaluated real devices, discussing characteristics, engagement factors, target populations, implementation strategies and preferences. Conversations were recorded, transcribed and thematically analysed.

Results

Three themes emerged: device-, person- and environment-specific factors impacting acceptability. Facilitators included inconspicuousness under the device theme and targeting subpopulations of PWUO at the individual theme. Barriers included affordability of devices and limited technology access within the environment theme. Trust in device accuracy for high and overdose differentiation was a crucial facilitator, while trust between technology and PWUO was a significant environmental barrier.

Discussion and Conclusions

Determinants of acceptability can be categorised into device, person and environmental factors. PWUO, on the whole, require devices that are inconspicuous, comfortable, accessible, easy to use, controlled by trustworthy organisations and highly accurate. Device developers must consider how the type of end-user and their environment moderate acceptability of the device.

Key Points

- Qualitative study found variable acceptability of mHealth for opioid overdose detection.

- Overarching themes: device-, person- and environment-specific.

- Different factors, facilitators and barriers will determine engagement of end-users.

- Crucial device characteristics are accuracy, battery life and inconspicuousness.

1 INTRODUCTION

Drug-related deaths involving an opioid in England and Wales are at an all-time high (2219 deaths in 2021) [1], while Scotland's opioid-related death rate remains the highest in Europe (1119 deaths in 2021) [2]. Naloxone is an effective antidote to opioid overdose; however, delivery of naloxone is dependent on the overdose being witnessed and recognised [3-6]. Detection of overdose and effective communication to responders could save many lives each year.

Adoption of wearable technology, such as smartwatches, has surged in recent years [7]. In parallel, mobile health (mHealth), including use of wearable devices, to remotely measure and treat a wide range of health conditions has expanded [8]. Respiratory depression is a physiological hallmark of opioid overdose, in which there is disruption of the regular breathing rhythm, suppression of breathing and potential respiratory failure. Devices are now being designed [9] and repurposed [10, 11] with the aim of detecting opioid overdose using various measures or responding to crises events [12-14]. Determining the acceptability of wearable devices and the facilitators and barriers of use is a necessary step in the development of new technologies demonstrated in a range of medical conditions [15-18]. End-user acceptability of wearable technologies is especially pertinent for people who use opioids (PWUO) where marginalisation, public stigmatisation [19] and socioeconomic disadvantage can reduce engagement with services, undermine treatment efforts and exacerbate health inequalities [20].

Limited research has examined acceptability of these devices to PWUO. In Philadelphia, USA, most of the sample of people who use opioids (76%, n = 96) reported willingness to wear an overdose-detection device; a discreet and comfortable watch was considered most acceptable [21], a clothing tag has been shown to be feasible [10] and an app that connects people who use opioids to responders was deemed positive [22]. In Vancouver, Canada, 54% (n = 1000) of people who use drugs reported willingness to wear an overdose detection device; having overdosed, being in methadone treatment and not being homeless were associated with willingness [23]. In Northern Ireland, focus groups of people who previously used illicit opioids found a commercial smartwatch to be generally acceptable and subsequently demonstrated successful device data transfer from participants (n = 3) to the study team [24]. A qualitative study from Scotland explored acceptability among PWUO (n = 9), affected family members (n = 4) and service workers (n = 17) and identified high overall willingness to use these devices and crucial modulating factors such as trust, the type of end-user and avoiding interruption of the ‘high’ [25].

This study aimed to further understand acceptability of opioid overdose detection devices in PWUO from England, where beliefs and attitudes may differ from North America, Ireland and Scotland. We conducted interviews and focus groups with 24 individuals with current or historical opioid use, from both stable and unstable (hostel) accommodation. We presented a variety of devices which participants interacted with during discussions (Table S1, Supporting Information). We aimed to investigate barriers and facilitators to acceptability of wearable devices that detect opioid overdose in a wide range of devices.

2 METHODS

2.1 Research design

A cross-sectional qualitative approach, utilising both semi-structured interviews and focus groups to gain both a breadth of information and facilitate sensitive personal disclosures was employed [26]. For participants living in a hostel, interviews ensured a private setting and made participants feel comfortable. Focus groups within a community setting enabled exploration of a range of opinions. The study was conducted by Will Lawn and Basak Tas, who received formal training in conducting semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Will Lawn, Basak Tas, Hollie Walker, Rebecca A. S. Evans and Elena V. Traykova received formal training in thematic analysis using Nvivo. Faith Matcham supervised qualitative data collection and thematic analysis. A standards for reporting qualitative research checklist is included in the Supporting Information.

2.2 Study setting

Three focus groups and seven interviews were facilitated by two researchers (Basak Tas and Will Lawn). All focus groups and interviews were conducted in person throughout March to June 2022, with seven private interviews taking place at King's College London (n = 3) and Providence Row Hostel, London (n = 4). Focus groups were conducted at Nottingham Community Hall (n = 7), Open Road Drug Service, Kent (n = 5) and King's College London (n = 5).

2.3 Participants

Participants were eligible if they were over 18 years of age and used illicit opioids, or took prescribed opioids in a non-prescribed way for at least 3 months. Convenience sampling was utilised via posters in drug services, hostels, Twitter posts and word-of-mouth. The study enrolled 24 participants and aimed to include a diverse range of individuals with current or historical opioid use and differing housing status. The total participant number was informed by previous qualitative device acceptability studies [18, 27]. Participants provided written informed consent and received £15 per hour for their time and reimbursed travel expenses. Procedures were approved by King's College London Ethics Committee (Ethics code: HR/DP-21/22–28508). Pseudonyms have been used throughout to de-identify participants.

2.4 Qualitative data collection: Semi-structured interview and focus groups

Consent was reiterated prior to discussion as was the importance of all voices being heard (focus groups). Participants were reminded they could pause, stop or leave the discussion at any point without giving a reason. In both focus groups and interviews a topic guide was designed to structure an open discussion (Data S1, Supporting Information). Participants were given the physical devices (Apple Watch series 6, Pneumowave chest sensor, Go2Sleep and Oura smart ring generation 2, and Spire Health clothing tag) and shown images of devices and their specifications (Table S1). Interviews lasted between 35 and 50 min and focus groups lasted between 80 and 120 min.

2.5 Quantitative data collection

Participants completed a demographics and drug-use questionnaire prior to commencement. Demographics data included gender, age, ethnicity, income, housing and marital status. For drug-use, participants self-assessed if they identify as a current or a former user, if they have used in the previous month and how much (including days per week, amount [mg] or money spent on heroin each day) and, for people who previously used heroin, how long they had used for. The questionnaire recorded recent use of other substances and previously experienced or witnessed overdose events.

2.6 Quantitative data analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported for demographic and drug-use questionnaires. Means and standard deviations are reported for continuous data. Absolute numbers and percentages are reported for categorical data.

2.7 Qualitative data analysis

Interviews and focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional, independent transcriber. An inductive approach to coding the qualitative data into low-level, granular codes, was undertaken by Hollie Walker according to Braun and Clarke's six-stage process [28, 29] (Table S2, Supporting Information) using Nvivo (version 1.6.1 January 2022). Relationships between codes were analysed by Hollie Walker and categorised based upon central organising concepts derived from developing codes and iterative notetaking. The resulting structure of high-level, mid-level and subthemes (full ‘theme map’; Figure S1, Supporting Information) was collaboratively reflected on by three other researchers (Basak Tas, Will Lawn and Faith Matcham) to achieve richer interpretations of meaning. Transcripts were deductively re-analysed in Nvivo by two researchers working independently (Rebecca A. S. Evans and Elena V. Traykova) to sense-check the resulting structure.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participants

3.1.1 Demographic data

There was a total of 24 participants, 79% (n = 19) were male and 21% (n = 5) female (Table 1). The average age of participants was 46 years (range = 27–64), and the majority were White (n = 20) with fewer Black (n = 1) and mixed-race (n = 3) participants. All participants were housed, with the majority in social housing (n = 12) and five participants in hostel accommodation (Table 1). Most participants owned a smartphone (n = 17) and had internet access at home (n = 17) (Table 1).

| Mean | SD | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender identity | ||||

| Female | 5 | 21 | ||

| Male | 19 | 79 | ||

| Age | ||||

| Female | 39.6 | 5.9 | 5 | 21 |

| Male | 47.7 | 9.4 | 19 | 79 |

| Total | 46.0 | 9.3 | 24 | 100 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 20 | 83 | ||

| Black | 1 | 4 | ||

| Mixed | 3 | 13 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 1 | 4 | ||

| Never married | 20 | 83 | ||

| Divorced or separated | 3 | 13 | ||

| Housing status | ||||

| Owned | 1 | 3 | ||

| Private rented | 6 | 25 | ||

| Social housing | 12 | 50 | ||

| Hostel | 5 | 21 | ||

| Income | ||||

| £0 | 3 | 13 | ||

| £1–£9999 | 16 | 67 | ||

| £10,000–£24,000 | 4 | 17 | ||

| £25,000–£29,000 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Technology access | ||||

| Currently own a smartphone | 17 | 71 | ||

| Currently has home internet access | 17 | 71 | ||

| Ever used a wearable device | 5 | 21 |

3.1.2 Drug use data

Participants presented a variety of opioid use histories, with most participants reporting current heroin use (n = 15), of whom 33% (n = 5) reported other non-prescribed opioid use including fentanyl (n = 2). Of participants not using heroin (n = 9), 22% (n = 2) were receiving opioid substitution therapy and the remaining 78% (n = 7) reported no opioid use at all (Table 2). Those who reported using heroin in the past 30 days (n = 15) used an average of £45 (SD = 21.6) of heroin per day across an average of 3.9 days per week (SD = 2.2). Of those who reported having not used heroin in the past 30 days the average length of their use spanned 17 years (SD = 7.1).

| Mean | SD | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants used heroin in last 30 days (N = 15) | ||||

| Days per week | 3.9 | 2.2 | 14 | |

| Time since past use (days) | 2.1 | 3.3 | 15 | |

| Amount per day (mg) | 600 | 532.7 | 13 | |

| Amount per day (GBP) | 45.7 | 21.6 | 11 | |

| Severity of dependence score | 7.5 | 2.1 | 15 | |

| Other non-prescribed opioid use | 13 | 86.6 | ||

| On opioid substitution therapy | 11 | 73.3 | ||

| Route of administration: Intravenous | 5 | 33.3 | ||

| Route of administration: Inhalation | 9 | 60 | ||

| Route of administration: Intranasal | 1 | 6.7 | ||

| Participants not used heroin in last 30 days (N = 9) | ||||

| Use period (years) | 17 | 7.1 | 8 | |

| Days per week | 6.4 | 1.7 | 9 | |

| On opioid substitution therapy | 2 | 13.3 | ||

| Other substance use: Past 30 days (N = 24) | ||||

| Alcohol | 11 | 45.8 | ||

| Benzodiazepines | 5 | 20.8 | ||

| Crack-cocaine | 12 | 50 | ||

| Cocaine | 3 | 12.5 | ||

| Fentanyl | 1 | 4.2 | ||

| Methamphetamine | 2 | 8.3 | ||

| Synthetic cannabinoids | 0 | 0 | ||

| Previous overdose (N = 24) | ||||

| Previous personal overdose | 15 | 62.5 | ||

| Previous witnessed overdose | 22 | 91.7 |

- Note: ‘N’ refers to the number of participants that have responded to the question.

Of all participants, 62.5% (n = 15) had personally experienced an overdose and 91.7% (n = 22) had witnessed someone else's overdose.

3.2 Qualitative results

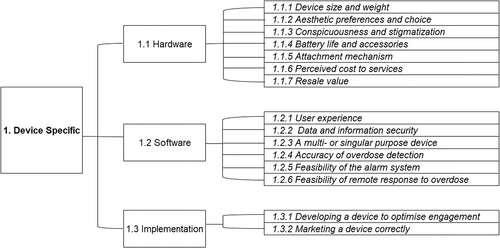

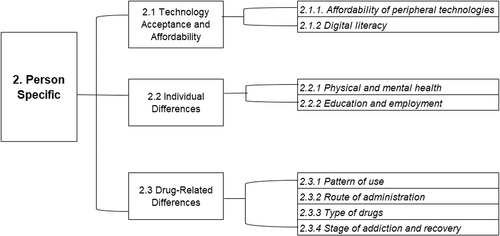

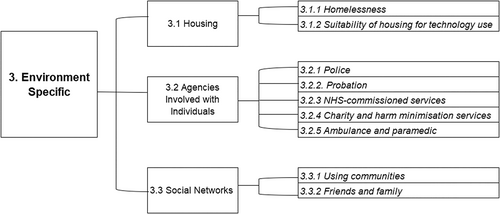

Our thematic analysis produced a three-level hierarchical structure of themes pertaining to factors that affect acceptability, facilitators and barriers to use of wearable devices. The structure consists of 3 top-level themes (‘device-specific’, ‘person-specific’ and ‘environment-specific’), 9 mid-level themes and 32 subthemes (Figure S1).

3.2.1 Device-specific

When focusing on acceptability at the level of the device itself, participants were mainly concerned with the suitability of the device's hardware and software (Figure 1).

Hardware

‘… another issue with some of these perhaps is stigma. I worked full time in cheffing and restaurants, I managed to keep my addiction secret to an extent, or for most of the time. People ask what's that, what's that on here? … So, you might notice this [chest sensor], wouldn't you, underneath a shirt or something like that.’—Rahim, 27

‘But can we just draw it back and say no, actually, this is for drug addicts, and this is to save lives of drug addicts …’—Sarah, 32

‘I personally wouldn't want to wear something that looks like a bloke's ring [smart rings], or a bit of a hipster thing … I'd want something that looks like something I would wear …’—Fran, 37

‘The idea of charging it every day, yeah, for me personally not something I would have kept up with. Regardless of its lifesaving properties, you're still not gonna care a great deal, you're quite apathetic’.—Rahim, 27

‘… when I was a chaotic user, someone had given me one of these [smart watch] I would have sold it within 30 seconds, I would have found the first person who was prepared to pay me money for it and I would have sold it’.—David, 56

A non-branded, single- purpose device was considered to potentially reduce resale value.

Software

‘With opiates it's the fine line between the ultimate sense of contentment and peace and being dead is … In fact that's when you have the best bit. I'm talking from the point of view someone wants to get high, is when you're closest to it’.—Rahim, 27

‘I think that's a big question for people as well, is that information gonna be shared anywhere, is it your own information, does it belong to somebody else?’—Henry, 64

‘That would be good. Again, that would be more motivation, if it was a case of something, you know, it can track … Just the fact it [smart watch] could tell time would be handy, it provides another purpose. It seems crazy that saving you from an overdose is not enough, but to be entirely honest it's not’.—Rahim, 27

‘… it also needs to be marketed that it's open to everybody and it is accessible, and it's really easy to be able to navigate and use, you don't want it to be too talking tech terms …’—Simon, 41

‘Yeah, a question of the right people … if someone does overdose, basically the right people finding out, not everyone finding out … If someone goes to sleep, other things, and it starts beating, those people, they'd lose their job, they'd lose their friends, might destroy their marriage’.—Alex, 55

‘[If you can't open an unlocked door] That means it just makes it impractical then in that situation, because the person will just die. If you call the emergency services and they can't get in, they're just gonna die, aren't they’.—Gareth, 59

3.2.2 Person-specific

The person-specific theme concerned barriers and facilitators to acceptability related to the personal characteristics of the end-user (Figure 2). Nuance began to develop as the diversity of this demographic at the person-level became evident.

Technology acceptance and accessibility

‘You've just got to remember, I would say at least 30% of people that are using [opiates] don't have internet access, a smartphone, and the ability to use it. Ok, so we're eliminating 30% of probably the most likely people to overdose straight away with that’.—Mark, 40

‘What if I ain't paid my internet bill, because I wanted to get an extra stone this month or like week or something …’—Sarah, 32

‘So, I think there's a lot that's gonna come up against the demographic of people, because they haven't really had those opportunities [using smart technology], that's not been something potentially that they've grown up with, the tech aspect of it’.—Fran, 37

However, participants were keen to not underestimate the capabilities of PWUO and viewed digital poverty, rather than ability, as the cause of lower levels of digital literacy.

Individual differences

‘… so my mental health, some days I'll be absolutely fine, other days you've got no chance. Unless it's really easy to do that day it's not gonna happen’.—George, 48

Drug-related differences

‘If you use alone, definitely, 100%, definitely these devices could help, yes, all of them could help, because if you're by yourself and you go over then you're fucked’—Mark, 40

‘… some people I'd think quite happily incorporate that into the ritual of using. Especially if you're an IV user, you know, set it up as part of your process, set the app on then use’—Rahim, 27

‘The one I would use is the one I wouldn't want to think about. So, you put it on once, if it can be there for a month then fine, don't think about it, then whenever I'm using, again just don't think about it … the drug is the thing, and the more things that you don't have to think about before you take it the better’—Gareth, 59

‘People that's been discharged from long-term hospital, someone coming out of rehab that might relapse, people coming out of prison, they're the main market, because they're more at risk because their tolerance is gone’—Michelle, 47

‘… I just think it depends where you are in your recovery. If you're coming to the end of treatment or have finished treatment, then the watch possibly could be an option, but not while you're still in active addiction’.—Janet, 44

3.2.3 Environment-specific

The environment-specific theme considered the surroundings of the end-user and its effect on the acceptability of devices. This included living arrangements and interaction with services (Figure 3).

Housing

‘… we're talking about it [breathing sensor app] being in a house, when we are in active addiction, we've been very chaotic, and I can say at many a time I've not had a one single space that I could say that's my space to be able to use that’.—Simon, 41

Agencies involved with individuals

‘Unless you made the police aware of the new devices. And these devices would come with a card, like sort of identity card explaining what it's for … I've been stopped for naloxone before, like got stopped and searched, just random, police making themselves busy’.—Michelle, 47

‘So, they're the most common interaction, and it's the sort of place where you get the most encouragement perhaps to wear this, your keyworker can remind you, are you wearing your device?’—Rahim, 27

‘I think it should be mandatory for those people, you know you go in for drug use, and when you're coming out of prison it's part of your probation you use it’.—Jamie, 51

‘Someone's overdosed, you phone an ambulance. Even if you've got naloxone, that's the most important thing you have to do’.—David, 56

Participants demonstrated concern that devices which automatically contacted emergency medical services would be wasting public service's time in the event of a false positive.

Social networks

‘My partner at the time would have wanted me to wear it. She would have probably encouraged me to keep it’.—Rahim, 27

4 DISCUSSION

This study explored facilitators and barriers to acceptability towards a range of devices among people who used or use heroin, gathering our information from individuals living in London, Kent or Nottingham. Our results indicate enthusiasm from participants towards a broad range of devices. However, there were heterogeneous beliefs about conditions that increase or detract from acceptability, identified as relating to the device, person and environment, which cumulatively influenced device acceptability.

Noticeably, PWUO identified accuracy of overdose detection and inconspicuousness as important facilitators to adoption, whereas poverty (digital and monetary), and trust in technology and services were crucial barriers.

4.1 Key findings

4.1.1 Acceptability

Participants echoed previous findings with the conceptual acceptability of a broad range of devices [22-24, 27]. Demonstrating enthusiasm towards a potential solution to an evident gap in current harm-reduction efforts. Participants frequently evidenced lifesaving potential, where device capabilities were applied to real-life overdose scenarios in which they could have provided better outcomes.

4.1.2 Device level factors

Accuracy of detection was unanimously found to facilitate acceptance and was of increased importance in our findings than when implicated in other studies [21, 25, 27]. An inaccurate device, unable to detect an overdose and differentiate between an optimal state of being high and an overdose, would be unacceptable, cause irritation and discontinuation of device use. This concern is not new in qualitative research relating to overdose situations, where PWUO report hesitance to respond to overdose situations, where the drug-taker is known to prefer an extreme state of high [30]. Technology could provide a detection accuracy impossible through human intervention and resolve a barrier to overdose response. However, participants' emphasis on accuracy relating to protection of their high may demonstrate a lack of faith in professional bodies having their interests at the forefront of development. There is considerable work that is required in this area and research which incorporates assessment of accuracy in relation to the ‘fine line’ between extreme high and overdose should be considered.

Specific hardware features were found consistently preferable such as lighter, waterproof and longer battery life devices. Yet, distinctly acknowledged to facilitate acceptability, was a device which provided discretion. Building on previous studies [21], our results indicate discretion would facilitate acceptability across all device types, driven by a desire to avoid stigmatisation. Discretion as a facilitator for use of wearables is not unique to PWUO [31-33] but the ability of a device to identify PWUO to employers, police or members of the public and face potential maltreatment, reinforces the need for inconspicuousness [25]. Training for non-specialist professionals is recommended to combat stigmatising attitudes towards PWUO. Through design, implementation, or both, discretion and reduced stigmatisation would facilitate the adoption of wearable devices [32].

4.1.3 Person level factors

The frequency of opioid sub-population specific considerations caused contradictions within subthemes regarding acceptability of device types, related to a range preferences such as, route of administration, polysubstance use and engagement with treatment. For example, a chest-sensor was considered more acceptable for PWUO in employment as its ability to be used ‘as and when’ increased discretion. Yet, the same device was perceived as unacceptable to people who also used crack-cocaine with heroin, due to itching sensations exacerbated by its skin-contact. ‘As and when’ versus continually worn devices were divisive and dependent on the person level factors. It was evident that any potential device will not be a catch-all solution and contradictions indicate it would be useful for developers to specify their end-user, beyond broadly ‘PWUO’. Projects commencing from design would benefit from an iterative user-centred process with particular interest to identifying drug-related preference which could impact on hardware. For repurposed or ‘off-the-shelf’ devices, consideration of the hardware specifications including mechanism of attachment, body position and removability may enable them to identify their end-user.

When identifying an end-user an appealing strategy may be to identify individuals otherwise disengaged with harm-reduction and facing complex needs, to provide a solution to harder to reach, underserved populations. However, our analysis identified that individuals of ‘high risk-high benefit’ faced multi-thematic barriers—encompassing device, individual and environment and were therefore perceived to lack the facilities for meaningful engagement and reduced efficacy of intervention. Research in Scotland found similar results, whereby willingness to engage and individuals in high need of solutions were considered not compatible, constituting a ‘readiness double bind’ dilemma [25]. Readiness to accept an intervention was considered a recovery decision, echoed in part within our stage of addiction recovery subtheme. Our participants did, however, identify opportunities to overcome the double-bind which often presented at points of involuntary engagement with peripheral services and where risk of overdose is increased (prison-release, probation and release from hospital admission). Despite findings across wearable device acceptability research indicating addiction and harm-minimisation services to be conducive to developing trust in an intervention [21, 25, 27], identification of peripheral services as potential stakeholders should be investigated as alternate routes to reaching underserved populations.

4.1.4 Environment level factors

Trust presented as a persistent barrier to engagement, featuring more pervasively in the environment level theme where in line with current research trust in the services providing and managing the device was required to facilitate acceptability [25]. Which, in turn, impacted trust at the device level relating to its accuracy and information security. Our findings add to the growing evidence base for trust as a fundamental challenge in new technologies for use in opioid overdose, where studies with both younger and higher smartphone using samples also report distrust towards devices [24, 25]. Our participants presented similar solutions to trust-related barriers, through engaging counsellors, health services and people in recovery to mitigate distrust outside of addiction literate circles [22, 25]. However, the degree of influence these solutions would have on what has been identified as a pervasive barrier to engagement [25] and complex socio-technical phenomenon, cannot be identified until later stages of implementation.

A further environmental barrier was limited access to technology and the peripheral facilities to manage such devices (e.g., charging point access, stable Wi-Fi), as supported by other studies [27]. Despite technology adoption among underserved populations having increased globally [33-35], our findings demonstrate that digital inclusion is vulnerable to complex socio-political factors [36]. Access to smartphones and the associated hardware was not solely deemed a barrier because of their cost at purchase, but also impacted by retention of devices, that is, where a device could be sold to obtain illicit drugs or be stolen. This underpinned the view that unbranded, cheap devices would facilitate use, by reducing desirability, value and risk of theft or re-sale.

4.2 Strengths and limitations

The ability for participants to physically handle a range of devices is novel in research into acceptability of wearable devices to PWUO, allowing for device specifications to be thoroughly considered. Furthermore, our study has the largest number of PWUO as participants from any qualitative study investigating this topic from the British Isles.

Participants did not wear devices for extended periods of time which can provide depth of insight into usability and the feasibility of technologies to collect accurate data [24]. Participants were predominantly White (n = 17), male (n = 15), heterosexual (n = 15), currently in treatment (n = 14) and from the Greater London area (n = 17) with a sample from Nottingham. While this may be representative of those who are in treatment for opiate addiction in Greater London [37], the sample may not to be representative of the population of PWUO as a whole and variation in drug-consumption patterns throughout the United Kingdom specifically limit generalisability.

5 CONCLUSION

Wearable technologies which detect and respond to opioid overdose are an anticipated advancement in harm-minimisation, showing potential to support currently underserved populations of PWUO. To inform development of devices, our thematic structure gives a framework for identification of barriers and facilitators which can guide improved acceptability for many end-users. Lack of trust was identified as a prominent barrier and crucial determinant in the uptake of devices and we extend the scope of prior research, identifying digital exclusion as opposed to smartphone access, as a broader barrier to use. Early-stage identification of proposed end-users will allow for person-specific adaptations to be accounted for during development. Future developments must be informed by consideration of concerns identified as pertinent by PWUO, so that devices can accurately detect overdose and differentiate a true overdose situation from a sought-after non-overdose state of high. This will be essential as these future devices will also need to meet the criterion of trust between the relevant target populations of individuals who use opioids and the devices that are developed for them.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Basak Tas: conceptualisation, design, data collection, analysis, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. Hollie Walker: analysis, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. Will Lawn—conceptualisation, design, data collection, analysis, writing—review and editing. Faith Matcham: design, writing—review and editing. Elena V. Traykova: analysis, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. Rebecca A. S. Evans—analysis, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. John Strang—conceptualisation and writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript. Each author certifies that their contribution to this work meets the standards of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to everyone who participated in our research. We would like to specifically thank Open Road, Providence Row, members of our Patient and Public Involvement group from London, Nottingham and Glasgow. We would like to extend thanks to PneumoWave for providing access to their device for use in this study. This research was conducted with support from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at Maudsley and King's College London.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Basak Tas is supported by National Institute for Health & Care Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. John Strang is a researcher and clinician who has worked with a range of governmental and non-governmental organisations, and with pharmaceutical companies to seek to identify new or improved treatments from whom he and his employer (King's College London) have received honoraria, research grants and/or consultancy payments: this includes, last 3 years, MundiPharma, Camurus, Accord/Molteni, Pneumowave. For a fuller account, see http://www.kcl.ac.uk/ioppn/depts/addictions/people/hod.aspx. John Strang's research is supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. Basak Tas, Will Lawn and John Strang are working with PneumoWave (who are developing a sensor in this space) for a planned future study. The PenumoWave chest sensor was one of six devices presented to participants in this study. Will Lawn consults for the clinical research organisation AxialBridge. Hollie Walker, Faith Matcham, Elena V. Traykova and Rebecca A. S. Evans declare no conflicts of interest.