Does the early childhood education and care in India contribute to children's skill development?

Abstract

Early childhood education and care (ECEC) is a crucial intervention because of its long-term impact on child development. However, information concerning the effectiveness of the ECEC in developing countries like India is sparsely available. This empirical study drew upon primary data collected from India's eastern state, West Bengal and investigated whether attending preschool contributed to children's cognitive and social skill development. The study found that attending preschool did not provide dividends in the form of cognitive and social skill accumulation. Furthermore, attending private preschool was associated with socioemotional development but no cognitive development. Moreover, parents' education seems to be a strong predictor for child's development. Given the findings of this paper, preschools in India, both in the public and private sectors, would need considerable quality improvement to deliver developmentally appropriate ECEC to children. It is particularly relevant in the context of the new National Education Policy in India, which emphasises the need to provide universal access to high-quality ECCE to all young children across the country.

INTRODUCTION

Early childhood development is considered one of the crucial components of sustainable development. It also links to poverty reduction, health and nutrition, gender equality and ending violence. Evidence from around the globe, though mainly from developed countries, shows that children's attending early childhood education programmes is associated with cognitive gains and improved performance in school (Almond & Currie, 2011; DeCicca & Smith, 2013; Dumas & Lefranc, 2012; Elango et al., 2015; Gormley Jr. et al., 2008; Weiland & Yoshikawa, 2013; Yoshikawa et al., 2013). Children, who received early education and care, had a more significant human capital accumulation, resulting in higher employment and earnings (Becker, 1964; Heckman, 2000; UNICEF, 2016, 2017). Furthermore, early intervention is considered more decisive for children from disadvantaged backgrounds and the developing world, as children in these countries face several inequalities starting from early childhood (Dumas & Lefranc, 2012; Linda et al., 2017; Patrice et al., 2011; Waldfogel, 2015). However, there is limited evidence on whether formal pre-primary schooling is an effective model in developing countries.

In India, like many other developing countries, evidence of the benefits of ECEC programmes still needs to be provided. Studies were often primarily focused on the healthy development of children rather than other child development outcomes (Government of India, 2011). Although, some recent studies (Hazarika & Viren, 2013; Jain, 2018; Nandi et al., 2020) showed that attending the ICDS programme was associated with greater enrolment, fewer dropouts and better performance. However, the evidence needs to be more extensive on ECEC programs' impact on children's skill development, primarily cognitive and social skills. Besides, research on the impact of early childhood interventions in India primarily focuses on public interventions such as ICDS. Therefore, information on the effectiveness of other private ECEC provisions is sparsely available.

Given this backdrop, this study looks at possible dividends of attending ECEC facilities on children's cognitive and social skill accumulation. Based on the primary sample of 1369 children in grade one in elementary school from the eastern part of India, this study empirically enquires about the association between attending preschool and children's skill development. The sample comprised 684 boys and 685 girls in grade one, with a mean age of about 80 months. The objective is to answer the two interrelated questions: First, is attending any ECEC programme associated with better cognitive and social skill accumulation? Second, does the type of ECEC programme (public or private) attended provide any relative advantage to children? One point to note here is that the study does not aim to compare the performance of children from Anganwadi centres and private preschools, as considerable differences exist in the age of children, the language of instruction and the strategies and pedagogical practices used in these preschools. Instead, the study here aims to illustrate the relationship between children's skill development to the specific forms of ECEC (i.e. public and private). Besides, as the study is non-experimental, the study's findings showed association rather than claiming causality. Considering the dearth of research on the effects of ECCE on cognitive and social skill development from the developing context, this study is expected to contribute to policy and academia significantly.

BACKGROUND

Indian preschool education

India is home to approximately 20% of the world's child population in the age group of 0–6 years. India has one of the world's most extensive child development programmes, named the Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS), in operation since 1975, alongside relatively recently established private ECEC initiatives. The public preschools are administered under the ICDS programme and called ‘Anganwadi’ (meaning ‘village courtyard’). The services provided directly and exclusively through the ICDS programme to all children 0–6 years of age are the following: supplementary nutrition to children in the age group of 0–6 years and preschool education to children in the age group of 3–6 years. Besides, children also receive immunisation, periodic health check-ups and referral services through the ICDS. One Anganwadi worker (AWW) and one Anganwadi helper (AWH) run the daily functioning of each Anganwadi. These women undergo 3 months of training and 4 months of community-based training before their appointment. According to a recent estimate (Ministry of Women and Child Development, 2018), about 32 million children in the age group of 3–6 years enrolled in the preschool education component of ICDS. Despite widespread ICDS presence, only a tiny proportion of children receive ICDS services intensely. Significant variation exists in the functioning and coverage of the programme across states and regions. (Jain, 2018). Besides Anganwadi, entrepreneurs operate unregulated private preschools as separate enterprises or preschools attached to private primary schools. Private preschools of different scales and designs are steadily expanding across the country, not only in urban areas but also in rural and tribal areas in many states (Kaul et al., 2015). Although the targeted subscribers are usually economically well-off families, recent studies have found a growing trend of parents across different socioeconomic classes favouring private preschools over public preschools for their children (Ghosh & Dey, 2020; Rana & Sen, 2008).

In India, the highly competitive and increasingly commercialised education system profoundly influenced the ideas and expectations of ECE. Strategies and practices for school success often involve the assimilation of the culture of educational consumption of the dominant middle class. (Sriprakash et al., 2020, p. 332). Moreover, the recent discourse on ‘school readiness’ strongly shaped parents' aspirations and their choice of ECEC (Donner, 2006; Maithreyi et al., 2022; Sriprakash et al., 2020). School readiness is often understood as developing writing literacy skills, learning to obey discipline and assimilating dominant caste-class cultures. Formal early childhood education and access to multiple forms of educational capital, such as written literacy, discipline and dominant caste-class codes, are crucial for academic success. To catch up with these hegemonic aspirations and in the absence of suitable public provisions of ECCE to meet their requirements, parents, particularly from the lower socioeconomic strata, often send their children to the private ECEC provisions.

Parents often mention that children must be developed and prepared for formal schooling to succeed academically (Donner, 2006; Ghosh, 2019). In the absence of ‘adequate’ formal education in ICDS, private ECEC provisions are seen by the parents as the possibility through which school readiness could be achieved (Maithreyi et al., 2020, 2022; Sriprakash et al., 2020). Besides, parents' preference towards English medium education as the superior option leads to a rise in private preschools (Donner, 2006; Maithreyi et al., 2020). However, studies suggest that these preschools often apply developmentally inappropriate practices. Due to the lack of regulation or framework and increasing demand from parents, private preschools often focus on literacy and numeracy, which may need to be more developmentally appropriate for young children. In private preschools, young children were engaged in long hours of reading, writing (mainly in English) and rote memorisation, with minimal opportunities for play. Besides, corporal punishments were used by instructors as a disciplinary device (Sriprakash et al., 2020).

Hence, the preschool education component under ICDS is considered suboptimal on the one hand, and the educational practices of private preschools are mostly considered inappropriate on the other. Therefore, it is difficult for parents from lower socioeconomic strata to identify the so-called good development practices. Given the highly stratified market, they often invest in private preschools.

Related literature

Studies show that ECEC can contribute to child development in many ways: by improving school enrolment and retention rate and reducing school dropouts (UNICEF, 2001; World Education Forum, 2000), by narrowing the gap between children from different socioeconomic classes and, thus, ‘levelling the playing field’ (UNICEF, 2016, p. 41). The inequality in the development of human capabilities can and should be prevented with investments in early childhood education (Heckman, 2011).

However, for several reasons, it is not always convincing to infer about developing countries like India based on the results from high-income countries. As Kline and Walters (2016) pointed out, effect of preschool use may depend highly on a child's counterfactual activities, which heavily depends on the context. Therefore, the counterfactual use of children from developing countries is likely to differ from that of children from developed countries. Besides, preschool quality might be lower in developing countries as these countries often suffer from implementation challenges (Dean & Jayachandran, 2019).

A set of literature on the benefits of ECEC on children in developing countries shows mixed evidence (Aboud, 2006; Engle et al., 2011; Hazarika & Viren, 2013; Nakajima et al., 2019; Singh & Mukherjee, 2018). Research conducted so far in India on the effectiveness of ECEC provisions, particularly ICDS, can be categorised based on the effect of ECEC on the health and nutritional aspects of children (Bhasin et al., 2001; Dixit et al., 2018; Dutta & Ghosh, 2017; NIPCCD, 1992; Sharma & Gupta, 1993), on school-related outcomes such as enrolment and dropout. (Hazarika & Viren, 2013; Jain, 2018; Kaul et al., 2015; Nandi et al., 2020; NIPCCD, 2006) and on children's skill development (Dean & Jayachandran, 2019; Pandey, 1991; Singh & Mukherjee, 2018; Vikram & Chindarkar, 2020).

Very few studies in India have investigated the short- and long-term impact of ECEC on children's cognitive and social skills. Existing studies in this regard differ considerably in their scope and findings. Firstly, these studies vary concerning the phase of childhood considered. For example, whereas some (Dean & Jayachandran, 2019; Pandey, 1991) measured the impact of ECEC on cognitive development at an early stage of childhood, others (Singh & Mukherjee, 2018; Vikram & Chindarkar, 2020) looked into relatively older children.

Secondly, studies differ in how they define and measure child outcomes. On the one hand, studies (Pandey, 1991; Vikram & Chindarkar, 2020) based on purposively developed test modules based on conceptual skills, comprehension and object vocabulary in reading, writing and arithmetic. On the other hand, others (Dean & Jayachandran, 2019) used already available standardised test modules to assess children's reasoning, memory, language, mathematics, creativity and motor skills.

Secondly, studies differ in their findings. Whereas the study by Pandey (1991) found a positive influence of ICDS attendance on all sample children, Vikram and Chindarkar (2020) found a positive impact of ICDS primarily for girls and children from low-income families. Besides, the study by Dean and Jayachandran (2019) evaluating the impacts of attending a private kindergarten on child development in Karnataka found a positive effect on cognitive development but no effect on socioemotional development. The study by Singh and Mukherjee (2018) found that attending private preschool was associated with higher cognitive skills and enhanced subjective well-being at 12 compared to attending government preschools in India.

Finally, studies evaluating the impact of attending preschool also differ in the sources of identification, and the Indian context is mainly dominated by non-experimental studies. The reason could be the scarce availability of experimental data in preschool settings, which allows only a few randomised controlled trials in developing countries (Hazarika & Viren, 2013). Studies in India are based on selection-on-observables techniques and used either national or regional-level data (e.g., Jain, 2018; Nandi et al., 2020; Singh & Mukherjee, 2018; Vikram & Chindarkar, 2020). On the one hand, cross-sectional studies such as Jain (2018) and Nandi et al. (2020) were based on nationally representative data from the National Family Health Survey for 2005–06 and used non-experimental techniques. On the other hand, studies by Singh and Mukherjee (2018) and Vikram and Chindarkar (2020) used regional-level longitudinal data and tracked children over the years. Whereas some non-experimental studies relied on simple descriptive analysis (Chopra, 2012; Pandey, 1991), some others depicted multivariate analysis using controls for child and household characteristics (Jain, 2018; Singh & Mukherjee, 2018). In addition to ordinary least square estimation, Vikram and Chindarkar (2020) also used propensity score matching. They argued that omitted variable bias arising from unobserved factors might affect access to ICDS, and using only ordinary least square estimation may lead to bias.

In contrast, the study by Dean and Jayachandran (2019) relied on experimental design. They randomised scholarships to attend a specific private preschool for 2 years for four to six-year children. They assessed child development at three points: before, after 2 years of kindergarten and after the end of first grade. They further specified a reduced-form model for the effect of the scholarship offer and an instrumental variable model for the effect of attending preschool (Dean & Jayachandran, 2019, pp. 6–7).

Therefore, existing studies are far from convergence in their methods and findings, and there exists remarkably less research focusing particularly on preschool education. Given this backdrop, this study seeks to improve on the limited evidence on Indian preschools. The study uses primary data and multivariate regression technique to estimate the association between attending a preschool and child development; and also a plausible private-public preschool related gap in child development. Besides, it focuses on the immediate impact of preschool attendance which minimises the risk of other factors confounding the results. Moreover, the study considers general attributes of both cognitive and social skills, which allows an understanding of possible differential effects due to the different type of child outcome considered.

METHOD

Sampling and data

This study rested on primary data from 1369 children from one of the eastern states of India named West Bengal. The unit of analysis in this study is children in the first grade in primary schools, as this group comprises children with or without preschool experience. The sampling instrument used for this research was based on a multi-stage sampling procedure. Children in the first grade in different primary schools were selected from 169 villages and 75 Wards (an electoral sub-district of a corporation/municipal council or town board) in two West Bengal districts representing a population size of about 2 million. Out of 1390 primary schools in the sample region, 86% were publicly sponsored and about 14% were privately sponsored. The final sample represents 84 schools and 1369 children. Since the research objective was to compare children who attended any preschool with children without any preschool experience, children in the first grade were selected as they comprised children with and without preschool experience. Besides, studying first graders reduces the problem of having school-fixed effects and the difficulty of disentangling how much of the current performance is due to preschool attendance and how much is primary school-related.

The sample shows a considerable variation concerning preschool attendance, indicating that about 66% of the sample children attended preschool. Among the sample children who attended preschool, about 71% of children attended public preschool, i.e. Anganwadi and the rest attended private preschool. The socioeconomic composition of children is a crucial factor for child development because children's development is considered the result of the interaction between features of the child's environment and those around her (Myers, 1990). Table 1 provides information on the socioeconomic status of sample households.

| Variable | Number of households | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parents' education | Up to primary | 479 | 35 |

| Above primary and up to Secondary | 654 | 48 | |

| Higher secondary and above | 236 | 17 | |

| Father occupation | Not employed | 7 | .50 |

| Regular employment | 841 | 62 | |

| Casual employment | 506 | 37.50 | |

| Mother Occupation | Not employed | 1228 | 90 |

| Regular employment | 68 | 5 | |

| Casual employment | 70 | 5 | |

| Caste origin | General Caste | 970 | 71 |

| Backward Caste (S.C., S.T. OBC together) | 398 | 29 | |

| Religion | Hindu | 1062 | 78 |

| Islam and others | 306 | 22 | |

| Location | Rural | 1019 | 74.5 |

| Urban | 350 | 24.5 |

| Variable | Observation | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household income (INR) | 1368 | 6122 | 4218 | 1000 | 40 000 |

| Number of children | 1369 | 2 | 0.76 | 1 | 8 |

| Family size | 1369 | 4.5 | 1.40 | 2 | 18 |

- Source: Author's computation from primary data.

The data shows a substantial variation in household income among households, with an average income of around 6000 rupees per month. Besides, about 35% of parents were educated only up to the primary level and most mothers (90%) were not employed. Furthermore, there was also caste and religion-based variation in the sample. Overall, the sample allows a reasonable degree of variation in socioeconomic parameters.

Measurement of cognitive and social skills

The conceptual foundation of child development and school readiness has different dimensions. It is defined, by and large, as a set of competencies that enable the child to enter and participate in school (Carlton & Winsler, 1999; Snow, 2006; UNICEF, 2012). Among many components of school readiness, one crucial is adaptive behaviour which refers to non-academic aspects of school readiness (Gresham & Elliott, 1987; Oakland & Harrison, 2008). Generally, the early years' set of cognitive, linguistic and socioemotional competencies can enable the successful transition and adjustment to formal schooling (Kaul et al., 2017).

Given this backdrop, this study focuses on adaptive behaviour (Maithreyi et al., 2019) as the tool for assessing child development. Unlike studies conducted in India, which primarily used reading, writing and arithmetic skills as child outcomes, this study focuses more on the general attributes of cognitive and socioemotional development, which are relatively easier to observe without needing a standardised test module. Furthermore, using standardised test modules to assess children's skills may also lead to difficulties as these modules are often designed for high-income countries. Hence, they may not be suitable for the Indian early childhood education context. Therefore, instead of relying on more subject-specific skills, this study focused on relatively general concepts of cognitive skills such as attention and working memory, which are also considered essential for children's academic performance.

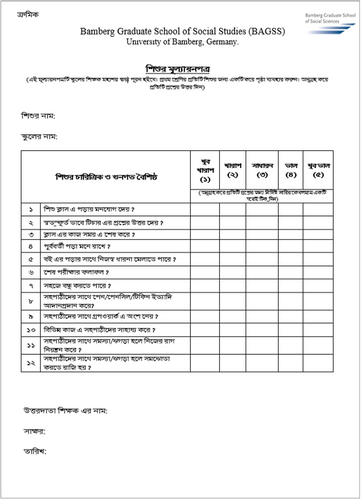

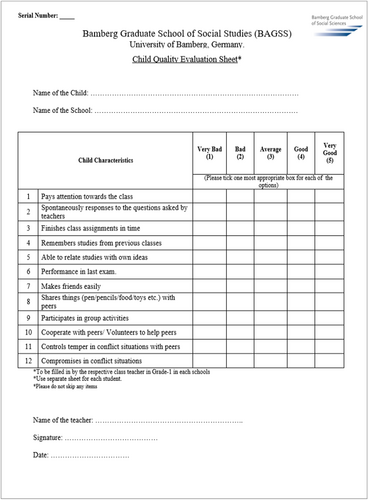

Considering the regional context and the curriculum used in existing preschools, a set of indicators was developed for this study, which covers essential cognitive and socioemotional development traits in children. The set of cognitive skills consisted of six attributes as follows: (i) attention towards class activities, (ii) ability to respond if asked questions, (iii) ability to deliver if given any task in class, (iv) ability to recall previous lessons, (v) ability to comprehend ideas, (vi) performance in the last class assessment. The set of socioemotional skills covers aspects such as (i) the ability to make friends, (ii) sharing food and other items with peers, (iii) participating in group activities with other peers, (iv) helping peers if needed, (v) controlling temper in conflicting situations and (vi) agree to compromise in conflicting situations. The respective class teachers assessed each child in the sample based on these indicators on a scale of five. Table 2 provides a descriptive summary of the indicators used in this study to assess child development.

| Variable | Freq. | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friendliness | 1369 | 3.915 | 0.746 | 1 | 5 |

| Share | 1369 | 3.831 | 0.784 | 1 | 5 |

| Help peers | 1369 | 3.815 | 0.814 | 1 | 5 |

| Group activities | 1368 | 3.839 | 0.801 | 1 | 5 |

| Control temper | 1369 | 3.783 | 0.779 | 1 | 5 |

| Compromise | 1368 | 3.812 | 0.776 | 1 | 5 |

| Attention | 1369 | 3.763 | 0.855 | 1 | 5 |

| Ability to response | 1369 | 3.661 | 0.907 | 1 | 5 |

| Classroom assignments | 1369 | 3.587 | 0.937 | 1 | 5 |

| Working memory | 1369 | 3.520 | 0.933 | 1 | 5 |

| Comprehend ideas | 1368 | 3.483 | 0.932 | 1 | 5 |

| School assessment | 1369 | 3.740 | 0.927 | 1 | 5 |

- Source: Author's computation from primary data.

Children who can regulate attention may more easily engage in classroom instruction, focus on assessments and complete assignments (Henderson & Fox, 1998; Rothbart & Jones, 1998; Rudasill et al., 2010). Besides, studies show that working memory (Miller-Cotto & Byrnes, 2020; Peng et al., 2018; Peng & Kievit, 2020) and children's ability to comprehend ideas (Baumann, 2010) significantly predict children's academic performance. Furthermore, children's ability to integrate with others, emotional self-control and behaviour in a socially acceptable manner is also considered critical social skills that predict school performance (Baumeister & Vohs, 2004; Boekaerts & Corno, 2005; Brownell & Kopp, 2007; Gottman et al., 1975; Zimmerman, 2002).

Children's cognitive and social skill accumulation was assessed using teacher ratings based on above mentioned 12 indicators using a Likert scale of five. In each school, the respective class teacher in the first grade was given a child assessment questionnaire designed in Bengali (see Appendices C and D) for each sampled child and was requested to rate the child's development in the school setting based on these 12 parameters using a Likert scale of five (1 = very bad, 5 = very good). Hence, each sampled child received a teacher rating for each of the 12 parameters. The rating occurred during regular school hours on working days. Since the teachers were interacting with these children for about a year, there were no difficulties assessing children by them, and there were very few missing (see Table 2). Ethical considerations were followed during the data collection, and all personal information, including students' scores on teacher ratings, was kept anonymous.

An exploratory factor analysis was then conducted using principal component analysis (henceforth PCA) for dimensionality reduction and generating indexes for children's cognitive and social skills. Two-standard criteria of component selection were used during the PCA. The (a) first criterion was based on the choice of one component of the eigenvalues which is greater than one and (b) the second criterion was the amount of explained variance, based on which the chosen factors should explain 70 to 80% of the variance of the variables selected (Jolliffe, 2002; King & Jackson, 1999). Finally, these components were included in generating the latent variable's value named ‘cognitive skills’ and ‘social skills’. Furthermore, the dependent variables, viz., cognitive and social skills (generated using PCA), were converted to their standardised form (with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one).

Control variables

Considering the context and household characteristics that might impact child development, several controls were introduced in the regression analysis. Monthly household income was included as an indicator of the household's economic status. Besides, parents' highest educational attainment, occupational status and family size were included as indicators of their social status. Dummies for caste and religion were used to identify the households by social group and religion. Furthermore, child characteristics such as the sex of the child and their health status were used. The geographical location (rural–urban) and district-wise fixed effects were also included in the models. Lastly, the duration spent in preschool by children, as reported by parents, was factored in.

Moreover, there is the possibility that teacher ratings vary by type of school. For example, if teachers in private schools are more likely to score higher for their children, and those schools are more likely to have children who enrolled in ECE. It would generate a correlation between the type of school and children's cognitive and social skills scores. Besides, given that the teachers do not observe the children's performance in isolation, one potential limitation could be the correlation between teachers' perception of one of the child's attributes and other attributes. Therefore, the study introduced a school-fixed effect during regression analysis. This variable allows controlling for all unobserved school-specific factors which can affect the outcome and check the robustness of the findings. Moreover, as the curriculum and practices differ in different schools, children may perform differently on skill assessments, and the school-fixed effect reflects those differences in skills.

Identification strategy

The empirical analysis of the paper can be divided into two parts: First, using descriptive statistics (presented in Tables 3 and 4) to understand the nature of the relation between preschool attendance and child outcomes and, Second, using confirmatory analysis which is primarily based on multivariate regression techniques. A multivariate regression analysis takes multi-collinearity among variables into account and provides better insight into the dependency between the dependent and the independent variables compared to any univariate analysis. As the study aims at providing non-causal estimates, the study deployed an ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation which gives correct linear projections. OLS is known for being robust to a variety of data generating processes and specification errors1 for the outcome, and provide consistent non-causal linear approximations of the conditional expectations (Wooldridge, 2010, pp. 49–55).

| Skill type | Indicators | Attended preschool—Yes | Attended preschool—No | t-test, p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Cognitive skills | Attention | 3.85 | 0.79 | 3.57 | 0.94 | .001 |

| Ability to response | 2.59 | 0.60 | 2.32 | 0.74 | .001 | |

| Classroom assignments | 3.69 | 0.87 | 3.38 | 1.01 | .001 | |

| Working memory | 3.60 | 0.89 | 3.35 | 0.98 | .001 | |

| Comprehend ideas | 3.57 | 0.88 | 3.30 | 1.00 | .001 | |

| School assessment | 2.62 | 0.60 | 2.41 | 0.71 | .001 | |

| Social Skills | Friendliness | 3.96 | 0.70 | 3.83 | 0.81 | .003 |

| Share | 3.87 | 0.72 | 3.74 | 0.87 | .007 | |

| Group activity | 3.84 | 0.75 | 3.76 | 0.91 | .09 | |

| Help peers | 2.69 | 0.49 | 2.55 | 0.63 | .001 | |

| Control temper | 3.81 | 0.72 | 3.72 | 0.87 | .05 | |

| Compromise | 3.85 | 0.72 | 3.72 | 0.86 | .006 | |

- Source: Author's computation from primary data.

| Skill type | Indicators | Public preschool | Private preschool | t-test, p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Cognitive skills | Attention | 3.78 | 0.81 | 4.03 | 0.70 | .001 |

| Ability to response | 2.53 | 0.64 | 2.73 | 0.49 | .001 | |

| Classroom assignments | 3.57 | 0.91 | 3.98 | 0.69 | .001 | |

| Working memory | 3.47 | 0.92 | 3.93 | 0.70 | .001 | |

| Comprehend ideas | 3.44 | 0.90 | 3.89 | 0.72 | .001 | |

| School assessment | 2.54 | 0.63 | 2.81 | 0.43 | .001 | |

| Social Skills | Friendliness | 3.93 | 0.72 | 4.03 | 0.64 | .03 |

| Share | 3.82 | 0.75 | 4.00 | 0.65 | .001 | |

| Group activity | 3.79 | 0.78 | 3.97 | 0.68 | .001 | |

| Help peers | 2.64 | 0.51 | 2.79 | 0.42 | .001 | |

| Control temper | 3.76 | 0.73 | 3.94 | 0.67 | .001 | |

| Compromise | 3.81 | 0.74 | 3.95 | 0.64 | .006 | |

- Source: Author's computation from primary data.

RESULT

The descriptive statistics in Tables 3 and 4 showed a substantial variation in children's skill accumulation based on preschool attendance and type of preschool. The independent sample t-tests show that children who attended preschool had a higher cognitive and social score than those who did not. A similar pattern was noticed concerning the preschool type, where children who attended private preschool had relatively higher cognitive and social skills scores than those who attended public preschool. In most cases, these differences were statistically significant. At the next level, the regression analysis examines the association between preschool attendance (and type of preschool) and children's skill accumulation in multivariate settings.

The estimations of the association between preschool attendance and child's skill accumulation are presented in Table 5 where the first column represents equation (i) and the second column represents equation (ii). The findings from the OLS analysis show a positive but statistically insignificant association between attending preschool and children's cognitive and social skills. A similar observation by Gupta (2020) in recent time showed that attending public preschools does not have a significant advantage over children who start primary school with no preschool experience. Among other covariates, parents' educational level significantly and consistently predicted children's cognitive and social skill accumulation. The higher the level of education the parents achieve, the higher the skill accumulation by children. Besides, the association of parental education was much more substantial for cognitive skills than social skills. For example, parent's higher secondary or above education, in general, associates with .66 standard deviation increase in cognitive skill and only .36 standard deviation increase in social skill in comparison to parents only with primary education. Considering the importance of parental level of education in children's skill formation, further sensitivity analyses were performed for each of the education groups. The findings (see Appendix A) do not differ from our original results presented in Table 5. Even after considering each education groups separately, there was no statistically significant association between preschool attendance and children's skill accumulation.

| Cognitive skill | Social skill | |

|---|---|---|

| Preschool attended (Ref. Not attended) | 0.100 | 0.144 |

| (0.209) | (0.194) | |

| Sex of the child (Ref. Female) | ||

| Male | −0.068 | −0.084* |

| (0.048) | (0.044) | |

| Child has illness (Ref. No) | ||

| Yes | −0.184* | −0.0986 |

| (0.096) | (0.089) | |

| Caste (Ref. Other castes) | ||

| General caste | 0.076 | 0.0229 |

| (0.062) | (0.057) | |

| Religious origin (Ref. Minority) | ||

| Hindu | 0.269*** | 0.182** |

| (0.096) | (0.089) | |

| Father age | 0.008 | −0.001 |

| (0.008) | (0.007) | |

| Mother age | −0.006 | −0.001 |

| (0.009) | (0.008) | |

| Parents' education (Ref. Up to primary) | ||

| Above primary but up to secondary | 0.449*** | 0.160*** |

| (0.060) | (0.056) | |

| Higher secondary and above | 0.666*** | 0.369*** |

| (0.096) | (0.089) | |

| Mother occupation (Ref. No emp.) | ||

| Regular emp. | 0.040 | −0.126 |

| (0.127) | (0.118) | |

| Casual emp. | 0.107 | 0.064 |

| (0.131) | (0.121) | |

| Father occupation (Ref. No emp.) | ||

| Regular emp. | −0.044 | −0.277 |

| (0.331) | (0.307) | |

| Casual emp. | −0.103 | −0.444 |

| (0.330) | (0.306) | |

| Residing district (Ref. Murshidabad) | ||

| Howrah | 0.332 | −0.639 |

| (0.487) | (0.451) | |

| Residing location (Ref. Rural) | ||

| Urban | 0.625 | 0.475 |

| (0.382) | (0.545) | |

| Household income | 1.04e-05 | 9.79e-07 |

| (8.16e-06) | (7.57e-06) | |

| Number of children | −0.066 | −0.062 |

| (0.041) | (0.038) | |

| Family size | −0.004 | 0.010 |

| (0.020) | (0.019) | |

| Daily preschool duration | 0.0001 | −0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| School fixed effect (for 84 schools) | Result omitted | |

| Constant | −0.622 | −0.431 |

| (0.610) | (0.566) | |

| Observations | 1350 | 1349 |

| R-square | 0.372 | 0.461 |

- Note: Robust standard errors in parenthesis.

- *** p < .001.

- ** p < .01.

- * p < .05.

Besides, being a Hindu associated with significantly higher cognitive and social skill accumulation. However, the caste-based social hierarchy had no significant correlation with children's skill accumulation. Moreover, the study finds no region-wise effects with respect to the districts or rural–urban inhabitation. Moreover, the R-square values from all the equations indicate a good precision of these models and the fit of the data.

The next set of results in Table 6 shows the association between the type of preschool attended and skill accumulation for those children who attended any preschool. Here the two columns represent equation (iii) and equation (iv), respectively. As evident from the existing literature that the choice of private preschool was often driven by the hope of cognitive development of children, the result of this study presented in the first column shows no statistically significant association between attending private preschool and children's cognitive skill accumulation. However, the coefficient was statistically significant for social skills and attending private preschool was correlated with .33 standard deviation point increase in social skill of children compared to attending public preschool. Therefore, in contrast to previous findings (e.g., Dean and Jayachandran (2019) that attending private preschool has a positive effect on cognitive outcomes but not on socioemotional outcomes), this study found that those who attended private preschools exhibited significantly more social skills but not cognitive skill.

| Cognitive skill | Social skill | |

|---|---|---|

| Preschool type-Private (Ref. Public) | 0.195 | 0.337*** |

| (0.136) | (0.122) | |

| Age of the child | −0.001 | 0.010** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| Sex of the child (Ref. Feale) | ||

| Male | −0.088 | −0.115** |

| (0.057) | (0.051) | |

| Child has illness (Ref. No) | ||

| Yes | 0.111 | 0.135 |

| (0.138) | (0.123) | |

| Caste origin (Ref. All other castes) | ||

| General caste | 0.159** | 0.104 |

| (0.075) | (0.069) | |

| Religious origin (Ref. Minority) | ||

| Hindu | 0.305** | 0.115 |

| (0.122) | (0.109) | |

| Father age | 0.018* | 0.006 |

| (0.009) | (0.008) | |

| Mother age | −0.017 | −0.009 |

| (0.010) | (0.009) | |

| Parents' education (Ref. Up to primary) | ||

| Above primary but up to secondary | 0.438*** | 0.076 |

| (0.077) | (0.069) | |

| Higher secondary and above | 0.606*** | 0.250** |

| (0.108) | (0.097) | |

| Mother occupation (Ref. No emp.) | ||

| Regular emp. | −0.101 | −0.219* |

| (0.133) | (0.119) | |

| Casual emp. | 0.044 | −0.018 |

| (0.145) | (0.130) | |

| Father occupation (Ref. No emp.) | ||

| Regular emp. | −0.089 | −0.436 |

| (0.467) | (0.419) | |

| Casual emp. | −0.102 | −0.567 |

| (0.470) | (0.422) | |

| Residing district (Ref. Murshidabad) | ||

| Howrah | 0.098 | −0.764* |

| (0.887) | (0.459) | |

| Residing location (Ref. Rural) | ||

| Urban | 0.176 | 0.172 |

| (0.848) | (0.761) | |

| Household income | 1.12e-05 | 1.70e-06 |

| (8.70e-06) | (7.81e-06) | |

| Number of children | −0.070 | −0.086* |

| (0.050) | (0.045) | |

| Family size | −0.009 | 0.001 |

| (0.024) | (0.021) | |

| Daily preschool duration | −0.0001 | −0.003** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| School fixed effect (for 84 schools) | Result omitted | |

| Constant | −0.479 | 0.142 |

| (0.837) | (0.752) | |

| Observations | 894 | 893 |

| R-square | 0.393 | 0.494 |

- Note: Robust standard errors in parenthesis.

- *** p < .001.

- ** p < .01.

- * p < .05.

Besides, parents' education also had a positive and statistically association mainly with cognitive skill accumulation. Those children with parents with relatively higher education levels scored higher in cognitive skills. Further decomposing the association across different education groups (see Appendix B) reveals that attending private preschool statistically significantly associated with better cognitive skills only to children whose parents had at least a higher secondary level of education, whereas, all education classes seem to benefit from attending private preschool in terms of social skill accumulation.

Overall, the findings of the study substantially contribute to the scant literature on the relationship between preschool attendance and child development, especially in a developing country's context. The possible explanations behind the findings are further discussed in the following section.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Discussion

This study aimed to answer whether attending preschool helps children's skill accumulation and whether the type of preschool has any relation with differential skill accumulation by children. The empirical evidence of the study suggests that after controlling for socioeconomic status and regional variations, attending preschool does not significantly associate with children's cognitive skill accumulation. Besides, attending private preschools correlated only with children's social skill formulation but no cognitive skill. The findings, therefore, raise the obvious question: Does attending preschool not substantially contribute to children's performance?

The question is compelling and points towards the quality and suitability of early education and care provided in the existing preschools in India. It is already established that the quality of the preschools may matter more for child development than attending preschool (Andrew et al., 2019; Krzewina, 2012; Ozler et al., 2018; Sharon et al., 2019; Yoshikawa et al., 2013). In this regard, both types of preschools in India are under scrutiny for the quality and developmentally appropriate practice for young children (Majumdar et al., 2021).

On one hand, the public provisions have received several criticisms for its reach and the quality of service provided for the preschool education component. Many of the Anganwadi centres still suffer from insufficient essential infrastructure availability, little pedagogic engagement, irregular staffing and student attendance (Alcott et al., 2018; Chopra, 2012; FOCUS, 2006; Kapoor, 2006; Pratichi, 2009). The focus is more on feeding rather than promoting behavioural change in childcare practices in the community (UNESCO, 2006). Parents and families emphasised that Anganwadi was a place for children to receive meals and health checks rather than a space for school-relevant learning (Sriprakash et al., 2020).

Additionally, Anganwadi workers often lack sufficient education and skills to take on these early educational responsibilities (NIPCCD, 2006, p. 30). It is argued that ICDS is not integrated into practice and focuses more on expansion than quality (Siraj-Blatchford, 2003). A significant issue emerges from the insufficient time spent on preschool education compared to what is prescribed in the Anganwadi centres (Maithreyi et al., 2020, p. 123). As a result, the preschool education component of the ICDS programme may function inadequately and fails to provide children with a developmental stimulus cognitive foundation.

Furthermore, preschool years are crucial because children establish their first friendships and acquire social skills that benefit them in school engagements and academic successes (Coolahan et al., 2000; Howes et al., 1998; Konold & Pianta, 2005; Ladd et al., 1988). However, public preschools are found not contributing to children's social skill development. This may due to several reasons ranging from lack of infrastructure to less attention towards children (Anganwadi workers) due to insufficient time available to Anganwadi workers. Another possible explanation could be related to children's purpose for attending public preschool (Anganwadi), which often is limited to a free meal (Ghosh & Dey, 2020; Sriprakash et al., 2020). It was also witnessed during the field visit that several children arrived at the Anganwadi centre just before the meal was served and left immediately after having their food. Some were also observed taking the food home instead of having it there with other children (Sabat & Karmee, 2021). The data also showed that the average daily duration of staying in preschool was significantly less for children attending public preschools (an average of 2 h) than those attending private preschools (an average of 3 h). This eventually reduces children's interaction scope and might affect their social skills.

Private preschools, on the other hand, were neither significantly better than Anganwadi centres nor appropriate for young children on many occasions. Though Anganwadi centres are far from perfect and need more infrastructure and materials, many private preschools were considered equally poorly equipped (Maithreyi et al., 2020). Studies evaluating the quality and functioning of private preschools in India also questioned the curriculum followed in private preschools for its quality and suitability for children (Chopra, 2012; Kaul, 1998; Kaul & Sankar, 2009; Swaminathan, 1998). Private preschools often engage in age-inappropriate pedagogical practices, with little to no focus on other critical domains of development, which may adversely affect children's learning capacities (Maithreyi et al., 2020, pp. 131–132). A more rigourous pedagogical approach in private preschools does not significantly change the extent of social interaction among children (Dean & Jayachandran, 2019, p. 17). Therefore, both types of ECEC provisions in India lack quality in contributing to children's cognitive development.

However, regardless of their strong focus on the academic-centric curriculum (Gupta, 2020), private preschools were found associating to children's better social skills accumulation. A straightforward explanation to this incidence is not possible as private preschools in India differ substantially in their curriculum and scale of operation, and information is sparsely available on them. Yet one possible explanation could be that the private preschools are often relatively well equipped with infrastructure and play materials; and have lower student-teacher ratio. Moreover, the teachers (or caretakers) in these preschools are usually are graduates, and have some training and pedagogical knowledge. This eventually allow these teachers to focus better on individual children and involve children into activities which involves more peer interactions. This might have contributed to better socioemotional skill accumulation by children. These findings open the scope for further research with particular focus on the functioning and quality of private preschools.

Another important aspect of the study is that, it especially vouches for the role of parental education for children's cognitive development. It is already established that parents' educational attainment is a powerful predictor of a child's development outcomes (Davis-Kean et al., 2021), and parents relate to children's educational environment in multiple ways (Duncan & Magnuson, 2003; Eccles, 2005; Ghosh & Steinberg, 2022; Jeffery et al., 2006). ‘Parent educational attainment provides a foundation that supports children's academic success indirectly through parents’ beliefs about and expectations for their children, as well as through the cognitive stimulation that parents provide in and outside the home environment’ (Davis-Kean et al., 2021, p. 186). Therefore the study reconfirms the importance of parents' education for child development, especially in developing countries.

Conclusion

In India, with existing income and social inequalities and nutritional deprivation among children, ICDS, and other social security provisions can be practical tools for child development. Public provisioning of ECEC can be particularly beneficial for children from lower socioeconomic strata as majority of them still rely on these public provisions. Nevertheless, the ECEC facilities in India are not adequately beneficial for children's development due to their lack of focus on appropriate pedagogical practices. This study uncovers evidence of a nonsignificant relation between children's participation in early childhood development programs and their future development in a developing country. Evidence suggests that as access to preschool is no longer the main issue (Kaul et al., 2017), improving the quality of early childhood education is the prerequisite for the better development of children. Although the new National Educational Policy proposed to make attending preschool mandatory for children in the age group of 3–6 years (Govt. of India, 2020), it will not necessarily translate to improving the status of the children in the country unless the quality of ECEC provided, especially the preschool education component, is improved.

Hence, a framework is needed to promote developmentally appropriate practices in public and private preschools. For early childhood education and care to be more effective and improve children's cognitive and social outcomes, there is a need to invest in the necessary infrastructure and provide children with an effective ECEC. This will eradicate the initial differences among children from different socioeconomic classes and lead to a better future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author is grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments that improved the quality of the paper. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) (Funding number: GH 220/1).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The author has declared no conflict of interest.

Endnote

APPENDIX A: Parents' education-wise estimating the effect of preschool attendance on different skill types

| Cognitive skill | Social skill | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Above primary up to secondary | Higher secondary and above | Primary | Above primary up to secondary | Higher secondary and above | |

| Preschool attended (Ref. Not attended) | 0.519 | −0.110 | −0.0786 | 0.502 | 0.364 | 0.467 |

| (0.409) | (0.341) | (0.530) | (0.357) | (0.339) | (0.544) | |

| All other covariates | Result omitted | |||||

| Constant | 0.280 | −0.316 | −0.451 | −1.449 | −0.0963 | 1.030 |

| (1.240) | (0.864) | (1.541) | (1.084) | (0.860) | (1.582) | |

| Observations | 469 | 647 | 234 | 468 | 648 | 233 |

| R-square | 0.409 | 0.341 | 0.397 | 0.569 | 0.414 | 0.536 |

- Note: Robust standard errors in parenthesis.

- *** p < .001.

- ** p < .01.

- * p < .05.

APPENDIX B: Parents' education-wise estimating the effect of preschool type on different skill types

| Cognitive skill | Social skill | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Above primary up to secondary | Higher secondary and above | Primary | Above primary up to secondary | Higher secondary and above | |

| Private Preschool (Ref. Public preschool) | 1.667 | 0.0837 | 0.630** | 3.085*** | 0.311* | 0.476* |

| (1.190) | (0.201) | (0.247) | (0.945) | (0.196) | (0.256) | |

| All other covariates | Result omitted | |||||

| Constant | 1.847 | −0.865 | −1.080 | −1.094 | 0.398 | 0.856 |

| (1.714) | (1.109) | (1.680) | (1.364) | (1.078) | (1.743) | |

| Observations | 237 | 442 | 215 | 236 | 443 | 214 |

| R-square | 0.450 | 0.401 | 0.416 | 0.573 | 0.497 | 0.560 |

- Note: Robust standard errors in parenthesis.

- *** p < .001.

- ** p < .01.

- * p < .05.

Biography

Saikat Ghosh is a doctorate in empirical educational research, and currently working as a researcher at the Leibniz Institute of Educational Trajectories (LIfBi) in Bamberg, Germany. His research interest lies in empirical microeconomics, economics of education, and child development with particular focus on developing countries.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.